Highlights

-

•

Isolated sphenoid opacification is a rare pathology that is increasingly being described and it represents 1–2% of sinus infections.

-

•

The most frequent symptom associated with isolated sphenoid sinusitis is intractable headache.

-

•

Isolated sphenoid sinusitis is usually treated surgically and endoscopic transnasal sphenoidectomy is the preferred surgical technique.

-

•

Highly inflammatory diseases such as fungal infections may be associated with an increased risk of re-ossification of the sphenoid ostium following sphenoidectomy.

Keywords: Sphenoidal sinusitis, Sinusitis, Endoscopic sinus surgery, Sphenoid sinus, Transnasal sphenoidectomy

Abstract

Introduction

Isolated sphenoid opacification is a rare pathology. Unlike other sinusitis, the treatment is most often surgical. Only few studies reporting the recurrence rates with long-term follow-ups are available in the literature. In our experience, isolated sphenoid sinusitis tends to have a significant recurrence rate after a first surgical intervention. This study aims to describe our experience with patients operated for isolated sphenoid sinusitis and to compare our reoperation and complication rates with those reported in the literature.

Methods

We conducted an electronic chart review of patients operated at the CHU de Québec between 2007 and 2018 for isolated sphenoid sinusitis.

Results

29 patients were analyzed. All patients had a sphenoidectomy with a transnasal approach. The reoperation rate was 103% (3/29) and the mean recurrence time was 15 (9–26) months. Among the patients reoperated, 2 patients had a fungus ball and one had a mucocele. Both patients with fungal balls had reossification of their sphenoidal ostium whereas the patient with the mucocele rather had a mucosal closure. No patient encountered any serious post-operative complication. Median duration of follow-up was 44 months (IQR: 25–68) for the 29 patients analyzed in our study.

Conclusion

Reoperation rates reported in the literature are probably underestimated. Our series emphasizes the importance of long-term follow-up for these pathologies. Highly inflammatory and chronic conditions such as fungal diseases could be linked to an increase in the occurrence of relapses.

1. Introduction

Isolated sphenoid opacification is a rare pathology that is increasingly being described in the literature. Isolated sphenoid sinusitis represents 1–2% of sinus infections [1]. The sphenoid sinus is at the center of important structures: the dura mater, the pituitary gland, the cavernous sinus, the internal carotid as well as cranial nerves II, III, IV, V and VI [2]. The isolated involvement of this sinus most often results in an insidious and atypical presentation. Symptoms include retro-orbital or vertex headaches, naso-sinusal symptoms, decreased visual acuity, and diplopia [3]. When left untreated, isolated sphenoid pathologies can lead to serious complications such as permanent blindness, cavernous sinus thrombosis or critical infections of the central nervous system [4,5]. Unlike the treatment of other chronic rhinosinusitis, the treatment of isolated sphenoid opacification is mainly surgical [6]. Several surgical techniques have been described to address the sphenoid sinus with variable reoperation rates. However, only a few studies reporting the recurrence rates with long-term follow-ups are available in the literature. In our experience, isolated sphenoid sinusitis tends to have a significant recurrence rate after a first surgical intervention. This retrospective study aims to present our experience with the treatment of isolated inflammatory pathologies of the sphenoid sinus, and to describe recurrence, as well as complication rates for surgically treated sphenoid sinusitis.

2. Patients and method

We retrospectively reviewed the charts of 34 patients over 18 years old who underwent surgical intervention for isolated sphenoid sinus disease between September 2007 and June 2017. All patients were selected from the Hôpital Enfant-Jésus, the Hôpital Saint-Sacrement and the Hôpital Saint-François d’Assise, three hospitals affiliated to the CHU de Québec-Université Laval, a tertiary academic referral center in Quebec City, Canada. The institutional ethics board of “CHU de Quebec” approved the study (study number: 2018–4095). Only non-invasive inflammatory pathologies, defined as non-specific bacterial rhinosinusitis, allergic fungal rhinosinusitis, fungus balls and mucoceles were included in the analysis. For each patient, demographic characteristics and clinical characteristics were recorded. Demographic characteristics included: gender, age at diagnosis, comorbidities and past sinus surgery. Clinical characteristics included: symptoms at presentation, medical treatment before intervention and underlying pathologies. Pre-operative CT findings and post-operative CT findings in cases of recurrences were also recorded. Surgical technique used for all patients included in the study was a transnasal sphenoidectomy. All patients were operated by the senior author of the manuscript, who is an otolaryngologist specialized in anterior skull base surgery with over 15 years of experience. Criteria for surgical intervention included mucoceles, fungus balls, presence of intracranial complication at presentation, signs of chronic disease on CT and persistent disease after 2 months of medical treatment. Radiological signs of chronic inflammatory process were defined as bone thickening, sclerosis or erosion. All diagnoses were confirmed by pathologic and microbiologic analysis. Patients with extension to other sinuses or with a follow-up period of less than 2 months were excluded from this study. All patients were prescribed a minimum of 6 months of nasal corticosteroid treatment postoperatively. The decision to maintain topical treatment beyond 6 months was tailored to each patient based on clinical findings. Each medical follow-up included a sinusoscopy. A local debridement through the sphenoid opening was done when needed during follow-up visits. A CT-scan was ordered on follow-up visits when there were clinical signs of recurrence, such as apparent closure of the ostium or refractory symptoms. In fact, all patients whose ostia were not visible during the examination with optic fiber rhinoscopy underwent a control CT scan to rule out any recurrence. Major intra-operative and post-operative complications were analyzed. Major complications included CSF leaks, major bleeding, cranial nerve injury, CNS infections and intra-operative orbital trauma. Four patients were excluded from analysis because they were lost to follow-up and one was excluded because sphenoid sinus opacification was not caused by an inflammatory pathology. 29 patients were included in the final analysis. This case series was written in accordance with the PROCESS guidelines [7].

3. Surgical technique

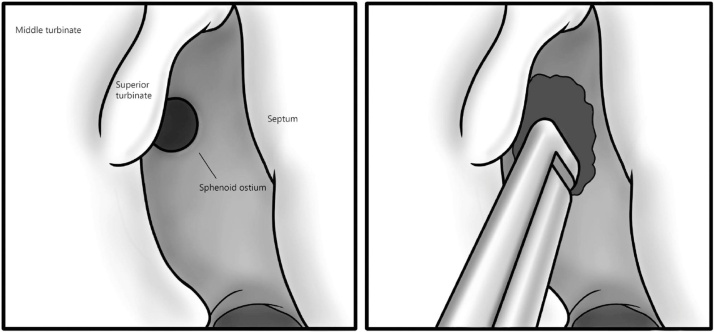

All procedures were performed endoscopically with a 3D intra-operative navigation system. The anterior aspect of the sphenoid is first identified with the upper turbinate laterally and the skull base superiorly. Resection of the lower portion of the upper turbinate is performed to improve the exposure if necessary. Mucosa of the anterior wall of the sphenoid is cauterized and the natural ostium is localized following the choanal arc. The ostium is opened with straight forceps, and then enlarged inferomedially with a 2 mm kerrison forceps or a drill in case of significant ossification (Fig. 1). The anterior wall of the sphenoid is widely open to the medial wall of the orbit, to the base of the skull above and to the floor of the sphenoid below. A large opening of the anterior wall of the sphenoid is obtained, joining the medial wall of the orbit laterally, the skull base superiorly and the floor of the sphenoid inferiorly. The sinus cavity is finally cleaned until visualization of healthy mucosa, and then copiously irrigated with physiological saline.

Fig. 1.

A. Identification of the superior turbinate, anterior aspect of the sphenoid and it’s natural ostium. B. Wide opening of the sphenoid ostium to the medial orbital wall and the skull base in the superior portion using the Kerrison forceps or a drill.

4. Results

Our population was composed of 23 female and 6 male patients. Median age at diagnosis was 639 years. 11 patients had a fungus ball (379%), 9 had chronic bacterial rhinosinusitis (31%), 5 had allergic fungal rhinosinusitis (172%) and 4 had a mucocele (138%). All patients were treated with a transnasal sphenoidectomy. (Table 1) The most common presenting symptom was headache (618%), mainly described as being retro-orbital or frontal. Other initial symptoms included posterior nasal discharge (559%), nasal obstruction (205%), facial numbness (147%), anosmia (5,9%), decreased visual acuity (5,9%), diplopia (2,9%) or others (265%). One patient presented with a cerebral abscess (3,4%). Nine patients (31%) were incidentally diagnosed during imaging done in the course of another investigation (Table 2). Resolution of cranial nerve deficit was seen in all patients. No patient encountered any serious post-operative complication. 3 of the 29 patients (103%, 95% CI: 2.2–27.4%) had recurrences, which required reintervention (Figs. 2, 3 & 4). Of these, 1 of 4 patients with mucocele had a recurrence (25%, 95% CI: 0.6–80.6%) and 2 of 11 patients with fungus ball had recurrences (18.2% 95% CI: 2.3%–51.8%). Mean time to recurrence was 15 (8–26) months. Median duration of follow-up was 44 months (25–68 months of interquartile range (IQR)) for the 29 patients analyzed in our study. Only 3 patients had a follow-up of less than 13 months, including 1 patient with a follow-up of 2 months only (Table 3).

Table 1.

Inflammatory sphenoid pathologies.

| Pathology | No. of patients | % |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic bacterial rhinosinusitis | 11 | 379 |

| Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis | 3 | 103 |

| Fungus Ball | 11 | 379 |

| Mucocele | 4 | 138 |

| Total | 29 | 100 |

Table 2.

Presenting symptoms.

| Symptoms | No. of patients | % |

|---|---|---|

| Headache | 21 | 618 |

| Posterior nasal discharge | 19 | 559 |

| Nasal obstruction | 7 | 205 |

| Facial numbness | 5 | 147 |

| Anosmia | 2 | 5,9 |

| Decreased visual acuity | 2 | 5,9 |

| Diplopia | 1 | 2,9 |

| No symptoms | 5 | 147 |

| Others* | 9 | 265 |

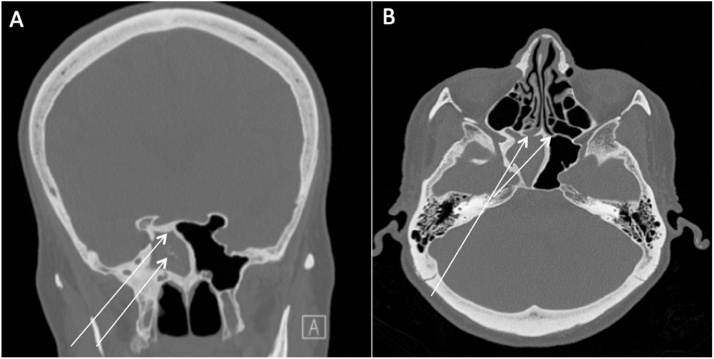

Fig. 2.

71 year-old female with right sphenoid fungus ball. A: initial CT scan showing right sphenoid fungus ball with hyperostosis and calcifications, B: recurrence of right sphenoid fungus ball with ostial ossification.

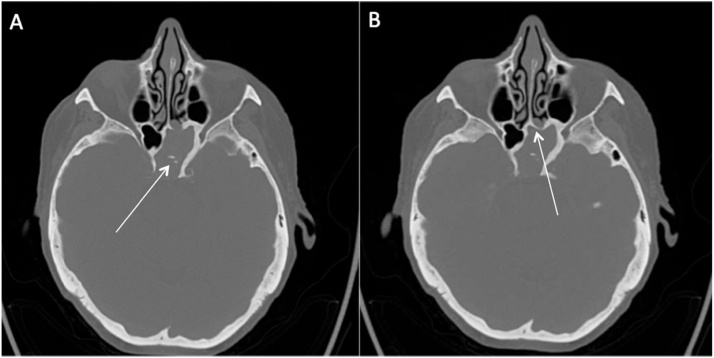

Fig. 3.

82 year-old female with left sphenoid fungus ball. A: initial CT scan showing bone thickenings, calcifications with posterior wall dehiscence and clival erosion. B: recurrence of left sphenoid fungus ball with ostial ossification.

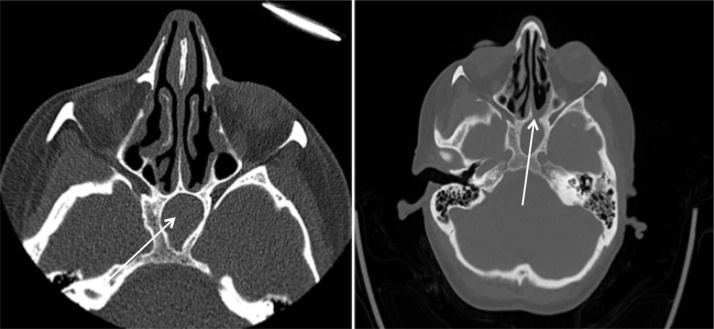

Fig. 4.

53 year-old female with left sphenoid mucocele. A: initial CT scan showing complete opacification of the left sphenoid sinus. B: recurrence of opacification with mucosal stenosis of the sphenoid ostium.

Table 3.

Recurrences.

| Case | Pathology | Time to recurrence (months) | Intra-operative findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fungus ball | 26 | Ossified ostium |

| 3 | Fungus Ball | 9 | Ossified ostium |

| 4 | Mucocele | 8 | Mucosal closure of the ostium |

5. Discussion

In our series, the majority of patients had intractable headaches (628%) as chief complaint. Most patient described them as being located at the retro-orbital, frontal or vertex region. The second most frequently reported symptom was posterior nasal discharge (559%) followed by other nasosinusal symptoms, such as nasal obstruction (205%). These findings were similar to already published data, with headaches reported to be present in 60–90% of patients [[8], [9], [10], [11]]. Cranial nerve deficits have been commonly described with sphenoid neoplasm but are also possible in inflammatory sphenoid diseases. Prevalence from previously published series ranges from 12 to 163% of patients [5,6]. In this regard, visual symptoms have been frequently described [12]. Decrease in visual acuity can be a result of inflammation or compression of the optic nerve whereas the diplopia is rather explained by a compromise of the trochlear, abducens or oculomotor nerves. In our study, only three patients (103%) presented with visual symptoms. Furthermore, involvement of the first or second branch of the trigeminal nerve is also commonly described, which may result in facial numbness or pain. In our study, a significantly higher proportion of patients (148%) presented with this symptom when compared to other series. Current literature is mostly retrospective and thorough evaluation of cranial nerves is inconstant. This could lead to an underestimation of the involvement of the trigeminal nerve in association with isolated sphenoidal sinusitis [3,5]. Finally, the disease was significantly more prevalent in women with a female to male ratio of 3.8:1. Median age at presentation was of 639 years. Both of these findings correspond to previously published data [13,14].

Unlike other sinusitis, isolated sphenoid sinusitis is usually treated surgically. Only few cases reported in the literature have responded completely with medical treatment alone [15]. Surgical intervention is required for cases of mucoceles or fungus balls, when there is a failure of a medical treatment for 6–8 weeks and when sphenoid sinusitis presents with complications [6]. Signs of chronic inflammatory process on computed tomography were also considered to be a surgical criterion in our study. Endoscopic transnasal sphenoidectomy is the preferred surgical technique for inflammatory diseases isolated to the sphenoid sinus, whereas the transethmoidal approach is frequently performed for cases of non-isolated sinusitis or tumors of the sphenoid sinus [16,17]. Balloon dilation of the natural sphenoid ostium has also been described for sphenoid sinusitis [18]. However, more studies evaluating the efficacy and safety profile of this procedure are needed. Given the refractory nature of this pathology, a large sphenoidectomy was undertaken on initial surgery to reduce the risk of postoperative closure [[19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]].

In our series, 3 patients had recurrence after their first surgical intervention, with a recurrence rate of 103%. In all cases, patients presented with pathologies known to be markedly inflammatory: 2 fungus balls and 1 mucocele. Chronic inflammatory diseases are associated with significant bone remodelling, especially in mucocele and fungus balls [12]. Signs of important chronic inflammation, such as ossification, bone sclerosis and erosions, were seen on pre-operative CT in all of these 3 cases. Intra-operatively, reossification of the previously opened sphenoid ostium was seen in both cases of fungus ball, whereas only mucosal closure was noted with the mucocele recurrence. The significant reossification that was noted in the recurrence case of fungus balls may be linked to the highly inflammatory process of such pathologies. Also, in both cases where there was a reossification, radiologic signs of long-standing inflammation such as bone sclerosis was far more significant than the other cases described in our series. This suggests that the level of inflammation of the underlying pathology and the duration of inflammation could be predictive factors for recurrence. Unfortunately, our study is underpowered to statistically prove such a hypothesis. Reossification of the surgically widened ostium has been previously described, but predictors of such cases remain unknown [21,25]. Further studies regarding the recurrence of chronic inflammatory disease of sphenoid sinusitis are needed to better understand the causes of such recurrences and to better address the pathology itself. It is also important to note that recurrences may occur late, which has been the case in our study. Mean time to recurrence was 15 months (8–26 months). Recurrence rate of inflammatory sphenoid sinus disease varies greatly in the literature, ranging from 0 to 20.8% [1,8,14,15,22,[26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37]]. Many authors have reported a high percentage of recurrences and reossification of the surgically opened sphenoid ostium. In their series of 96 patients with isolated sphenoid disease, Yu et al. reported reossification of 21 sphenoid ostium, of which 9 patients required reintervention [37]. Martin et al. reported a recurrence rate of 10.5% (2/19), with recurrences occurring as late as 6 years postoperatively [8]. Cakmak et al. had 13 recurrent cases out of 112 inflammatory sphenoid sinus diseases. In this study, 6 bacterial sinusitis recurred between 4 months to 8 years of follow-up, 5 mucoceles recurred between 3 months to 7 years and 2 fungal diseases recurred between 1–2 months after the first surgery [36]. Rosen et al. published a series of 17 patients with isolated lesions of the sphenoid sinus that were treated surgically. 3 of these patients had a sphenoidal ostium closure after six months of follow-up [38]. Leroux et al. reported 4 reinterventions for sphenoid ostium reossification in a case series of 24 patients [22]. In 2005, Castelnuovo et al. reported 28 patients operated for isolated inflammatory pathologies of the sphenoid sinus, 3 patients (107%) needed re-intervention. Mean time to recurrence was not specified, but all patients were followed over many years [24]. Massoubre et al. published a large series in 2016, with 79 patients operated for isolated inflammatory pathology of the sphenoid sinus. In this series, 8 patients required one or more reintervention, resulting in a recurrence rate of 10% [23]. This study is particularly relevant because it demonstrates the refractory character of inflammatory pathologies of the sphenoid sinus, with some patient requiring surgical intervention on 3 different occasions for recurrent sphenoid disease. However, many groups have presented series of patients with surgically treated isolated sphenoidal sinusitis for which recurrence rates were much smaller or even null [1,[26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]]. One of the reasons that may explain the difference between these low reported recurrence rates is the duration of follow-up. Indeed, several of these series have follow-up periods of less than 2 years and sometimes even less than 1 year. Also, many of these series have small number of patients, which can underestimate the recurrence rate due to a lack of statistical power. In our study, the median follow-up period was 44 months; a long enough follow-up period to adequately estimate the rate of recurrences. Furthermore, some series carried postoperative follow-up with telephonic encounters. Since recurrences may be asymptomatic, cases may be missed and therefore recurrence rate from these series are not interpretable [26,27].

Facing our cases of recurrences, we aimed to improve our surgical technique. In all three cases of reintervention, re-opening of the sphenoid ostium was performed. A merogel soaked in triamcinolone (kenalog) was also left in place and removed after two weeks with the intention of decreasing local scarring and limiting the inflammatory process. Other alternative techniques have been described in the literature for cases of refractory sphenoid pathologies. Among others, marsupialisation and nasalization, also called the “drill-out” procedure, were previously described [19,21,25]. The rationale of both these interventions is to obtain maximal exposure of the sphenoid cavity. Nonetheless, these techniques require more extensive dissections and may be associated with higher risk for surgical complications.

Because of its contiguity with many important structures, surgical treatment of sphenoid sinusitis is not without risk. Major complications such as CSF leaks, massive haemorrhage, CNS infections and orbital trauma have been reported [5]. In this matter, our study compares to the already published data with 0% of major complications. Indeed, Moss et al. reported a complication rate ranging from 0.1–3.2% for endoscopic surgical approaches of the sphenoid sinus in their meta-analysis [5].

Our study of course has some limitations. First, our case series is meant to be descriptive and no definitive conclusions can be drawn from it given the absence of statistically significant results. Furthermore, 2 patients had a follow-up of less than 6 months. Among the last 2 patients with a shorter postoperative follow-up, one died from another cause before his second follow-up, while the other chose to be followed by his general otolaryngologist. This may have led to an underestimation in the number of recurrences.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, we believe that recurrence rates reported in several studies might be underestimated. The too brief follow-up periods or too small number of patients in many case series could explain this underestimation. Our study therefore emphasizes the importance of long-term follow-up in cases of inflammatory diseases of the sphenoid sinus. Refractory cases have been reported in many series and late recurrences are not uncommon. As of now, there is no clear predictor of recurrences of sphenoid sinusitis after surgical treatment. Our observations lead us to wonder if the presence of marked chronic inflammation, as found in fungal diseases, could be a potential predictive factor of recurrence. Given the few studies of importance on the subject and the lack of guidelines governing the management of this pathology, it seems essential to contribute to the current literature by publishing our local experience. Adding new data to the present literature is paramount in understanding the causes of treatment failure and ultimately finding a better way to treat this pathology. Further studies, such as case-control studies, are needed to better understand the predictive factors of refractory inflammatory disease of the sphenoid sinus.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None of the authors of this manuscript have any conflict of interest to declare.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. This work was supported by the Oto-Rhino-Laryngology-Head and Neck Surgery research fund of the “Fondation de l’Université Laval.”

Ethical approval

The procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the CHU de Québec – Université Laval. Ethical approval the research ethics board from this institution was obtained.

Consent

The procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the CHU de Québec – Université Laval. Ethical approval from the research ethics board of our institution was obtained (request 2018–4095). Informed consent from patients was not deemed necessary as only clinical-administrative data and as no personal data were included in the manuscript. Publication approval was obtained from the research ethics board of our institution.

Author contribution

Dre Sylvie Nadeau performed patient diagnosis, investigations and treatments. Noémie Villemure-Poliquin and Sylvie Nadeau completed the literature review. Noémie Villemure-Poliquin and Sylvie Nadeau were the major contributors in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Registration of research studies

This research project was registered with the CHU de Québec – Université Laval before the first draft of the manuscript. Online registration was not required since this manuscript is a case series.

Guarantor

The senior author and guarantor of this manuscript is Dre Sylvie Nadeau.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Noémie Villemure-Poliquin: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. Sylvie Nadeau: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing - review & editing.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Andréa Villemure-Poliquin for the illustration included in the article.

Contributor Information

Noémie Villemure-Poliquin, Email: Noemie.villemure-poliquin.1@ulaval.ca.

Sylvie Nadeau, Email: sylvienad@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Marcolini T.R., Safraider M.C., Socher J.A., Lucena G.O. Differential diagnosis and treatment of isolated pathologies of the sphenoid sinus: retrospective study of 46 cases. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;19(2):124–129. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1397337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Proetz A.W. The sphenoid sinus. Br. Med. J. 1948;2(4569):243–245. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4569.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knisely A., Holmes T., Barham H., Sacks R., Harvey R. Isolated sphenoid sinus opacification: a systematic review. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2017;38(2):237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2017.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y.H., Chen P.Y., Ting P.J., Huang F.L. A review of eight cases of cavernous sinus thrombosis secondary to sphenoid sinusitis, including a12-year-old girl at the present department. Infect. Dis. (Lond) 2017;49(9):641–646. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2017.1331465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moss W.J., Finegersh A., Jafari A., Panuganti B., Coffey C.S., DeConde A. Isolated sphenoid sinus opacifications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2017;7(12):1201–1206. doi: 10.1002/alr.22023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charakorn N., Snidvongs K. Chronic sphenoid rhinosinusitis: management challenge. J. Asthma Allergy. 2016;9:199–205. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S93023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Farwana R., Koshy K., Fowler A.J., Orgill D.P. The PROCESS 2018 statement: updating consensus preferred reporting of CasE series in surgery (PROCESS) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018;60:279–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin T.J., Smith T.L., Smith M.M., Loehrl T.A. Evaluation and surgical management of isolated sphenoid sinus disease. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2002;128(12):1413–1419. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.12.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman A., Batra P.S., Fakhri S., Citardi M.J., Lanza D.C. Isolated sphenoid sinus disease: etiology and management. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2005;133(4):544–550. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilony D., Talmi Y.P., Bedrin L., Ben-Shosan Y., Kronenberg J. The clinical behavior of isolated sphenoid sinusitis. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2007;136(4):610–615. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruoppi P., Seppa J., Pukkila M., Nuutinen J. Isolated sphenoid sinus diseases: report of 39 cases. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2000;126(6):777–781. doi: 10.1001/archotol.126.6.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawson W., Reino A.J. Isolated sphenoid sinus disease: an analysis of 132 cases. Laryngoscope. 1997;107(12 Pt 1):1590–1595. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199712000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim T.H., Na K.J., Seok J.H., Heo S.J., Park J.H., Kim J.S. A retrospective analysis of 29 isolated sphenoid fungus ball cases from a medical centre in Korea (1999-2012) Rhinology. 2013;51(3):280–286. doi: 10.4193/Rhino12.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung J.H., Cho G.S., Chung Y.S., Lee B.J. Clinical characteristics and outcome in patients with isolated sphenoid sinus aspergilloma. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2013;40(2):189–193. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nour Y.A., Al-Madani A., El-Daly A., Gaafar A. Isolated sphenoid sinus pathology: spectrum of diagnostic and treatment modalities. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2008;35(4):500–508. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pagella F., Matti E., De Bernardi F., Semino L., Cavanna C., Marone P. Paranasal sinus fungus ball: diagnosis and management. Mycoses. 2007;50(6):451–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2007.01416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elhamshary A.S., Romeh H.E., Abdel-Aziz M.F., Ragab S.M. Endoscopic approaches to benign sphenoid sinus lesions: development of an algorithm based on 13 years of experience. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2014;128(9):791–796. doi: 10.1017/S0022215114001832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yanagisawa K., Christmas D.A., Mirante J.P., Yanagisawa E. Balloon dilation of the sphenoid sinus ostium for recurrent sphenoid sinusitis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2016;95(8):310–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leight W.D., Leopold D.A. Sphenoid “drill-out” for chronic sphenoid rhinosinusitis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2011;1(1):64–69. doi: 10.1002/alr.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Zele T., Pauwels B., Dewaele F., Gevaert P., Bachert C. Prospective study on the outcome of the sphenoid drill out procedure. Rhinology. 2018;56(2):178–182. doi: 10.4193/Rhin17.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soler Z.M., Sindwani R., Metson R. Endoscopic sphenoid nasalization for the treatment of advanced sphenoid disease. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2010;143(3):456–458. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leroux E., Valade D., Guichard J.P., Herman P. Sphenoid fungus balls: clinical presentation and long-term follow-up in 24 patients. Cephalalgia. 2009;29(11):1218–1223. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2009.01850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Massoubre J., Saroul N., Vokwely J.E., Lietin B., Mom T., Gilain L. Results of transnasal transostial sphenoidotomy in 79 cases of chronic sphenoid sinusitis. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2016;133(4):231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castelnuovo P., Pagella F., Semino L., De Bernardi F., Delu G. Endoscopic treatment of the isolated sphenoid sinus lesions. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262(2):142–147. doi: 10.1007/s00405-004-0764-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donald P.J. Sphenoid marsupialization for chronic sphenoidal sinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2000;110(8):1349–1352. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200008000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao X., Li B., Ba M., Yao W., Sun C., Sun X. Headache secondary to isolated sphenoid sinus fungus ball: retrospective analysis of 6 cases first diagnosed in the neurology department. Front. Neurol. 2018;9:745. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eravci F.C., Ceylan A., Gocek M., Ileri F., Uslu S.S., Yilmaz M. Isolated sphenoid sinus pathologies: a series of 40 cases. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2017;47(5):1560–1567. doi: 10.3906/sag-1608-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Socher J.A., Cassano M., Filheiro C.A., Cassano P., Felippu A. Diagnosis and treatment of isolated sphenoid sinus disease: a review of 109 cases. Acta. Otolaryngol. 2008;128(9):1004–1010. doi: 10.1080/00016480701793735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kieff D.A., Busaba N. Treatment of isolated sphenoid sinus inflammatory disease by endoscopic sphenoidotomy without ethmoidectomy. Laryngoscope. 2002;112(12):2186–2188. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200212000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manjula B.V., Nair A.B., Balasubramanyam A.M., Tandon S., Nayar R.C. Isolated sphenoid sinus disease - a retrospective analysis. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2010;62(1):69–74. doi: 10.1007/s12070-010-0016-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim S.W., Kim D.W., Kong I.G., Kim D.W.Y., Park S.W., Rhee C.S. Isolated sphenoid sinus diseases: report of 76 cases. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008;128(4):455–459. doi: 10.1080/00016480701762466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lim H.S., Yoon Y.H., Xu J., Kim Y.M., Rha K.S. Isolated sphenoid sinus fungus ball: a retrospective study conducted at a tertiary care referral center in Korea. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274(6):2453–2459. doi: 10.1007/s00405-017-4468-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bowman J., Panizza B., Gandhi M. Sphenoid sinus fungal balls. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2007;116(7):514–519. doi: 10.1177/000348940711600706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pagella F., Pusateri A., Matti E., Giourgos G., Cavanna C., De Bernardi F. Sphenoid sinus fungus ball: our experience. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy. 2011;25(4):276–280. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2011.25.3639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Z.M., Kanoh N., Dai C.F., Kutler D.I., Xu R., Chi F.L. Isolated sphenoid sinus disease: an analysis of 122 cases. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2002;111(4):323–327. doi: 10.1177/000348940211100407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cakmak O., Shohet M.R., Kern E.B. Isolated sphenoid sinus lesions. Am. J. Rhinol. 2000;14(1):13–19. doi: 10.2500/105065800781602993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu H., Li H., Chi F., Dai C., Zhang C., Wang Z. Endoscopic surgery with powered instrumentation for isolated sphenoid sinus disease. ORL J. Otorhinolaryngol. Relat. Spec. 2006;68(3):129–134. doi: 10.1159/000091269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosen F.S., Sinha U.K., Rice D.H. Endoscopic surgical management of sphenoid sinus disease. Laryngoscope. 1999;109(10):1601–1606. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199910000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]