Highlights

-

•

A multidisciplinary team is mandatory for the correct management of hemorrhagic GIST and its complications.

-

•

There is a well-known association between type 1 Neurofibromatosis and GIST.

-

•

Type 1 Neurofibromatosis-GIST and sporadic GIST have different behaviour.

-

•

In case of localised and resectable GIST surgical treatment is the mainstay.

-

•

Laparoscopic approach, if performed correctly, is safe and effective with better short-term outcomes then open surgery.

Keywords: Small bowel GIST, Proximal jejunal GIST, GI bleeding, Type 1 neurofibromatosis, Laparoscopic surgery, Case report

Abstract

Introduction and importance

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is the most common mesenchymal neoplasm of the gastrointestinal tract. It may be asymptomatic; nevertheless, gastrointestinal bleeding is the most frequent symptom, due to mucosal erosion. Its poor lymph node metastatic spread makes GIST often suitable of minimally invasive surgical approach. The importance of this study is to increase the awareness among physicians about this condition in particular scenarios as in our case and to stress the role of laparoscopic surgery.

Case presentation

A 74-year-old female patient presented to the emergency department with hematemesis, followed by haematochezia and melena. The patient had a medical history of type 1 Neurofibromatosis (NF1). She underwent, after CT scan, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, and endoscopic haemostasis. Finally, we performed a laparoscopic resection of a mass of the first jejunal loop. The postoperative period was predominantly uneventful. Pathological examination confirmed a low-risk GIST.

Clinical discussion

Proximal jejunal GIST may cause an upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. A multidisciplinary team approach is mandatory for the correct management of this disease and its complications (bleeding). GISTs are indicated as the most commonly gastrointestinal NF1 associated tumours. In case of localised and resectable GIST surgical treatment is the mainstay and laparoscopic surgery is a valid alternative.

Conclusion

In case of abdominal bleeding mass in a NF1 patient, it is important to keep in mind the well-known association between NF1 and GIST to facilitate the diagnosis and to quickly perform the appropriate treatment. Laparoscopic approach is safe and effective if the oncological radicality is respected.

1. Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is the most common mesenchymal neoplasm of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract accounting for 0.1–1% to 3% of all GI neoplasms [[1], [2], [3], [4]]. GIST, first described by Mazur and Clark in 1983 [5], originates from interstitial cells of Cajal of the autonomic nerve system of the intestine [6]. It can arise in any GI tract from the esophagus to the rectum. Gastric localisation is most frequent (40%–60%) followed by small bowel (30%–40%) [7] and rectum (4%–5%) [2,8]. GIST may present as abdominal emergency, including GI bleeding related to pressure necrosis and mucosal erosion or ulceration. In this case the patient has a medical history of type 1 Neurofibromatosis (NF1), so we report on NF1 GISTs too. We present a case report and a literature review. The purpose of this study is to increase the awareness among physicians about these conditions and their association to facilitate the diagnosis and achieve a more rapid treatment.

This case report has been reported in line with the SCARE 2020 criteria [9].

2. Case report

A 74-year-old female patient was addressed to the emergency department of a peripheral hospital for hematemesis. Her past medical history included hypertension, type 1 Neurofibromatosis, cholecystectomy by open approach about fifteen years previously and appendectomy in adolescence. She was a non-smoker with a negative history of allergies. She had no prior history of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. At presentation, her haemoglobin was 8.0 g/dl for which she received two units of packed red cells. The patient was transferred to another hospital where she underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGDS) which failed to identify the source of bleed. During her return to the first hospital, she experienced another episode of hematemesis and was therefore transferred to the emergency department of our hospital.

She had several episodes of haematochezia and melena. Clinical examination showed a skin pallor and tachycardia but normotension. Physical examination of the abdomen was negative except for typical café-au-lait spots as well as multiple skin nodules. Digital rectal examination showed cherry red stool with blood clots followed by dark stool. Blood tests showed haemoglobin 7.3 g/dl, red cells 2.37 × 106 and haematocrit 20.8. An abdominal Computed Tomography (CT) scan was initially negative. She was transferred to the medical department. The patient then underwent an EGDS which showed evidence of an upper digestive haemorrhage at the level of a mass, with ulceration in the third duodenum without active bleeding. The following day the patient experienced further melena and blood clots, but with normal vital signs. An abdominal Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography (CECT) and abdomen CT angiography (CTA) revealed a hyperdense mass of third duodenum, diameter 33 × 24 mm and no active bleeding (Fig. 1a, b). After another episode of melena and blood clots with hypotension, we performed a second EGDS that demonstrated an active bleed from ulceration of the mass in the third duodenum (Fig. 2a, b). Haemostasis was performed using two titanium clips. She received two units of packed red cells. Angiography confirmed the tumoral neoangiogenesis and no blushing of contrast (no active bleeding) (Fig. 3a, b).

Fig. 1.

a, b: CECT and CTA showed a hyperdense mass and no active bleeding.

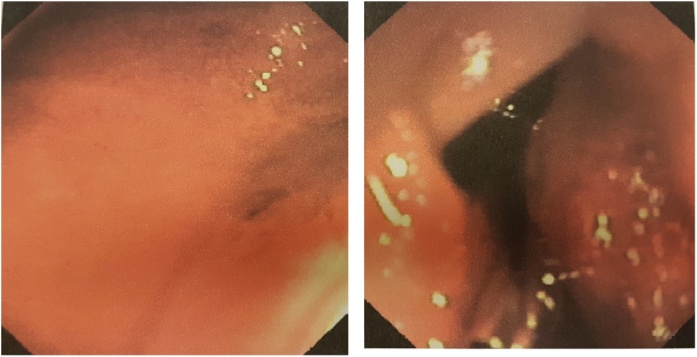

Fig. 2.

a, b: EGDS demonstrated an active bleeding from ulceration of the mass (a) and positioning of two titanium clips to perform haemostasis (b).

Fig. 3.

a, b: Angiography confirmed the tumoral neo-angiogenesis and no active bleeding.

The patient was transferred to our surgical department where we performed an exploratory laparoscopy. Surprisingly, we found a mass at the level of the first jejunal loop about five centimetres from the Treitz ligament (Fig. 4). We performed a laparoscopic wedge resection using a linear stapler (Fig. 5a, b). Moreover, there were multiple nodules in the whole small bowel wall (Fig. 6). The final surgical result highlighted the cosmesis and typical café-au-lait spots as well as multiple skin nodules (Fig. 7). The surgical team was skilled in laparoscopic surgery. In the post-operative period, an episode of anaemia was treated with two hematic transfusions (Grade II according to Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications). The abdominal drain, normal during the initial postoperative period, showed a clear liquid and laboratory tests confirmed the presence of lipase and amylase which resolved followed the administration of octreotide. On the 16th postoperative day (POD) she had a significant episode of melena and dark blood with an haemoglobin 7.4 g/dl receiving one unit of packed red cells. Postoperative evolution was favourable, and she was discharged home in good clinical conditions.

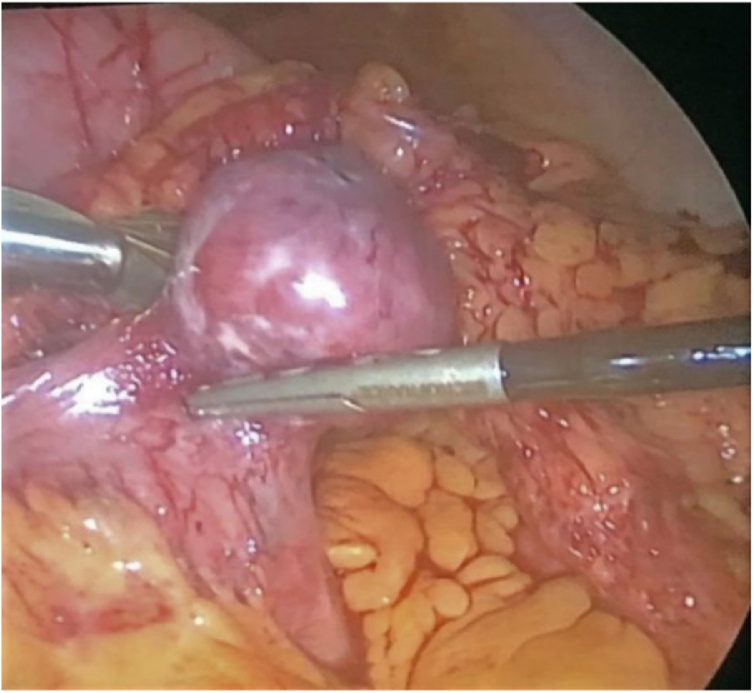

Fig. 4.

Intraoperative view - A mass at the level of the first jejunal loop about five centimetres from Treitz ligament.

Fig. 5.

a, b: Intraoperative view - Laparoscopic wedge resection with linear stapler (Endo-GIA).

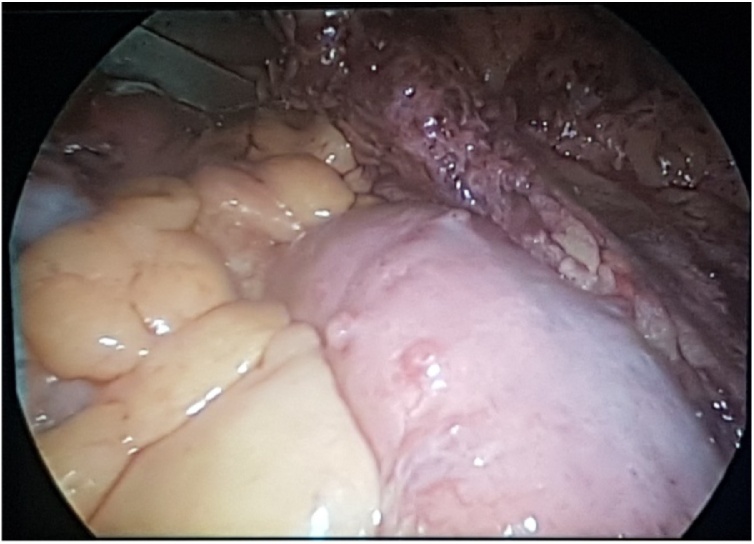

Fig. 6.

Intraoperative view - Presence of multiple nodules in the whole small bowel wall.

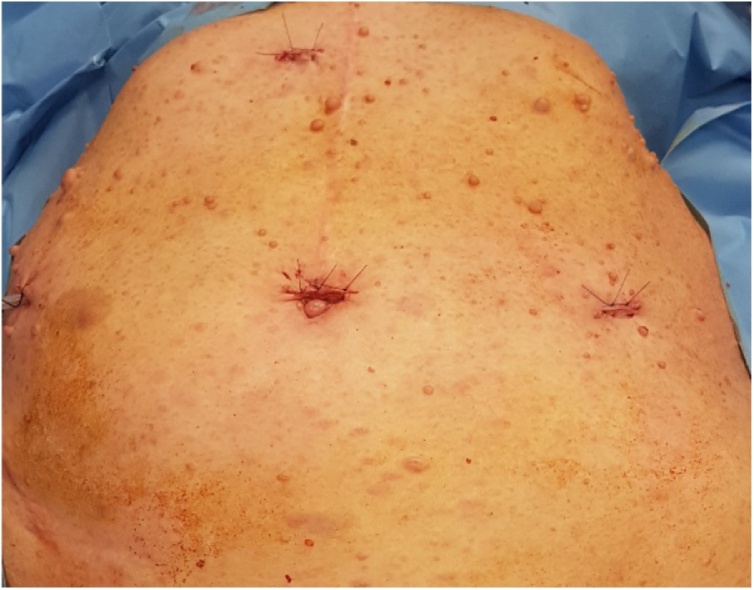

Fig. 7.

The final surgical result highlighted the cosmesis and typical café-au-lait spots as well as multiple skin nodules.

Histopathology showed a GIST, measuring 3.5 cm, composed of spindle cells with a mitotic count <5 per 50 High Power Fields (HPFs). Immunohistochemistry revealed a positivity for CD117, CD34 and DOG1 as well as a negativity for actin, desmin and S100. The Ki-67 proliferation index was low at 2%, with cut-off between high and low accepted as 10%. These findings confirmed a low-risk GIST.

The patient was referred to the dedicated Oncologist for the follow-up. After ten months of follow-up, she showed no signs of either local regression or distant metastases, as confirmed by negative PET-CT scan (Fig. 8a). General physical and abdominal examination were unremarkable (Fig. 8b).

Fig. 8.

a, b: Ten months follow-up: PET-TC scan (a), cosmesis after laparoscopic approach (b).

3. Discussion

In this article, we aim to highlight several aspects and findings of GIST, as observed in our clinical case: gastrointestinal bleeding, GIST site and size, another GIST entity namely NF1 GIST and their management and treatment, supported through a review of the current literature. Literature review was performed using PMC and Pubmed, including different key words and limiting the results to English language papers, which resulted in few works. However, additional articles were retrieved from the references of publications found via the keyword search and subsequently added to the review.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is the most common mesenchymal neoplasm of gastrointestinal (GI) tract and accounting for 0.1–1% to 3% of all GI neoplasms [[1], [2], [3], [4]]. Gastric localisation is most frequent (40%–60%) followed by small bowel (30%–40%) [7] and rectum (4%–5%) [2,8].

The site and size of GIST influences the clinical presentation and, above all, the management as well as surgical technique and approach, and finally the prognosis. In many cases, the patients present with non-specific and vague symptoms. One of the most common presentations of GIST, principally located in the small bowel, is obscure or overt GI bleeding [7,[10], [11], [12], [13]] related to pressure necrosis and mucosal erosion or ulceration [1,14,15]. In the latter condition, the GIST may present as abdominal emergency.

Computed tomography is the most accredited tool to detect a GIST, particularly contrast enhancement multi detector computed tomography (ce-MDCT), and can be employed for detection, staging and localisation as well as follow-up [1]. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) allows for the diagnosis of a small bowel tumour with GI bleeding with a reported diagnostic sensitivity of about 90% [1,16].

In case of bleeding, the diagnostic tools are different. In our case, there was both upper and lower GI bleeding. In the first evaluation upper and lower endoscopy are mandatory. If negative, in stable patients, and in case of obscure bleeding capsule endoscopy (CE) is the recommended first line procedure for small bowel evaluation. Deep enteroscopy, among which double-balloon enteroscopy, first developed and reported by Yamamoto [17], is employed in case of CE failure or severe and persistent bleeding [10,11,18,19].

In these cases, the primary objective is to establish haemostasis in order to stabilise the patient. Endoscopic and radiological procedures are the most accredited nonsurgical tools to halt bleeding, particularly EGDS, coloscopy, deep enteroscopy [18] and/or angiography and angio-embolization [20]. In case of small bowel GIST with life-threatening symptoms such as massive GI bleeding and in the absence of diagnosis, emergency exploratory laparotomy represents a diagnostic and therapeutic procedure [1].

Type 1 Neurofibromatosis (NF1, von Recklinghausen disease) is an autosomal and dominant disorder caused by the inactivation of the NF1 gene on chromosome 17, which is a tumour suppressor gene in some cell types, encoding the neurofibromin protein, a member of the RAS family [[21], [22], [23], [24], [25]]. This condition is characterised by cutaneous neurofibromas, café au lait macules, axillary and inguinal freckling, and Lish nodules. NF1 is associated with several tumours, including those of the GI tract, and GISTs are indicated as the most commonly GI NF1 associated tumours [25,26]. The incidence of GIST in the NF1 population is estimated to be markedly higher compared to that of the general population [[22], [23], [24]], although the frequency of NF1 GIST varies greatly in the literature, ranging from 5% to 29% [24,27,28]. Levy et al. [29] showed, significantly, in four out of five (80%) patients with multiple lesions, only one tumour was identified on preoperative CT scan, a finding reflected in our case. Many studies reported several differences between GISTs associated with NF1 syndrome and sporadic GISTs, in fact the literature would seem to demonstrate a distinct and peculiar phenotype of NF1 GIST: the predominant localisation is the small intestine rather than the stomach [4,23,[22], [23], [24], [25],29,30], with multiple localisations, occurring in younger patients. The estimated risk for malignancy is low [23], suggesting a good long-term prognosis [31], although one report concluded that NF1 GISTs are not always indolent and they can lead to death [23].

Surgical treatment is the mainstay of non-metastatic and resectable GIST [7,32]. The primary objectives are to achieve a radical surgical resection with negative margins (R0) and to avoid tumour rupture [2,7,33]. Considering the rarity of lymph nodes metastasis, lymphadenectomy is not indicated [2,7,33]. As previously mentioned, tumour site also influences the surgical strategy and approach, mainly in small bowel GISTs. In case of duodenal localisation (as supposed in our preoperative work-up), surgical technique is crucial for patient outcome. In fact, in case of duodenal GIST several studies [[34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39]] investigating different surgical strategies showed consequently different results in terms of morbidity, mortality, patient recovery and oncological outcome. The recommended surgical intervention, when possible, based on tumor size and location, is wedge resection; if it is not possible to achieve a surgical radicality a partial duodenectomy with reconstruction and, in some cases, a pancreatico-duodenectomy are described. The latter procedure presents worse outcomes compared to local or limited resection as demonstrated in two meta-analysis [34,35]. However, in another study, the surgical procedure was not an independent prognostic factor in multivariate analysis [38].

In case of jejunal or ileal GIST the treatment of choice is wedge resection or small bowel segment resections, and intracorporeal or extracorporeal anastomosis, without lymph node dissection [1,2,33].

Laparoscopic surgery is a valid alternative to open approach in case of resectable GIST. In the published literature, there are numerous studies documenting the short-term and oncological outcomes after laparoscopic approach in case of gastric localisation [2,[40], [41], [42]].

Small bowel GISTs have a low incidence compared to gastric location and this is reflected in the paucity of published papers comparing laparoscopic versus open approach in this patient group. These works show better short-term outcomes in favour of laparoscopy including reduced postoperative pain, decreased hospital stay, lower morbidity rate, and also importantly no difference in terms of overall survival and disease-free survival between the two approaches [2,33,[43], [44], [45]]. The largest meta-analysis on the topic [33] confirms these data and concludes by suggesting the safety and efficacy of laparoscopic surgery offers compared with open approach for small bowel GISTs, proposing nevertheless the necessity of multicentre randomised control trials (RCTs) to further address the real role of laparoscopic technique. Kim et al., in a review of literature, report the mean/median size of the GISTs laparoscopically resected with a range of 2.7–6.1 cm [2]. Surprisingly in our case, the tumour site supposed in the III duodenum was in the first jejunal loop. During laparoscopic exploration, we decided to perform a laparoscopic wedge resection with linear stapler (endo-GIA) of a small bowel mass between three and four centimetres in diameter.

Molecular pathogenesis is various and most GISTs show gain-of-function mutations in KIT gene (c-kit) [7,46], while in some cases there are activating mutations in PDGFRA gene [7,47]. Both genes encode for tyrosine kinase proteins, KIT and PDGFRa, respectively. These characteristics were found in so-called sporadic GISTs. In fact, these kinds of GIST are sensitive to imatinib, a selective inhibitor of certain tyrosine kinases, which is the standard treatment of locally advanced inoperable and metastatic GIST [7,32,48,49]. Several studies showed the application of this drug in adjuvant [1,48,49] or neoadjuvant treatment [34,49,50]. Sunitinib, another tyrosine kinase inhibitor, and regorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor, represent a standard second-line treatment [32,48,49] and third-line therapy respectively [48,49]. The introduction of tyrosine kinase inhibitors has dramatically improved the management of GISTs, prolonging recurrence-free survival after surgery and extending overall survival in metastatic or unresectable tumors [49].

On the other hand, the majority of NF1 GISTs showed the absence of Kit and/or PDGRFA mutations [25,28], for this reason, this type of GIST does not respond well to imatinib treatment [[23], [24], [25],28] which is considered ineffective and not recommended [23,50].

Tissue histology and immunohistochemistry are required for definitive diagnosis of GIST and to differentiate from other types of soft tissue tumors [1,7]. Many GISTs are positive to CD117 and/or to CD34 and to DOG-1; on the other hand, in most cases, GISTs are negative to actin, desmin and S100 protein. Tumor size and mitotic index are the first key prognostic factors described for the estimation of recurrence risk and malignant behaviour of GIST [51], to these are added tumor site and tumor rupture [7]. Based on literature data, therefore, there are three main risk-stratification methods to estimate the prognosis of GIST after surgery [38]: National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus criteria [51], Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) criteria [52] and modified NIH criteria [53], published by Fletcher in 2002 [51], Miettinen in 2006 [52] and Joensuu in 2008 [53], respectively (Table 1). In the last two classifications, tumor site is an additional prognostic factor. Ki67 is another important prognostic factor that influences recurrence and survival [49]. Compared with gastric GISTs, small bowel tumors of a similar size and mitotic index had a markedly worse prognosis in a large series with decreased recurrence‑free survival rate [33,54] as well as a higher rate of aggressive features [55].

Table 1.

Risk stratification criteria.

| Fletcher 2002 (50) |

Miettinen 2006 (51) |

Joensuu 2008 (52) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk category | Tumor Size (cm) | Mitotic index (HPF) | Tumor Size (cm) | Mitotic index (HPF) | Tumor site | Tumor Size (cm) | Mitotic index (HPF) | Tumor site |

| Very low risk | < 2 | < 5/50 | 2–5 | ≤ 5/50 | Stomach | ≤ 2 | ≤ 5/50 | Any |

| Low risk | 2–5 | < 5/50 | >5 ≤ 10 | ≤ 5/50 | Stomach | 2.1–5 | ≤ 5/50 | Any |

| 2–5 | ≤ 5/50 | Small bowel | ||||||

| Intermediate risk | ≤ 5 | 6–10/50 | > 10 | ≤ 5/50 | Stomach | ≤ 5 | 6–10/50 | Gastric |

| 5–10 | ≤ 5/50 | >5 ≤ 10 | ≤ 5/50 | Small bowel | 5.1–10 | ≤ 5/50 | Gastric | |

| 2–5 | > 5/50 | Stomach | ||||||

| High risk | > 5 | > 5/50 | 2–5 | > 5/50 | Small bowel | Any | Any | Tumor rupture |

| > 10 | ≤ 5/50 | Small bowel | > 10 | Any | Any | |||

| > 10 | Any | >5 ≤ 10 | > 5/50 | Stomach | Any | > 10/50 | Any | |

| > 10 | > 5/50 | Stomach | > 5 | > 5/50 | Any | |||

| Any | > 10/50 | >5 ≤ 10 | > 5/50 | Small bowel | ≤ 5 | > 5/50 | Non-gastric | |

| > 10 | > 5/50 | Small bowel | 5.1–10 | ≤ 5/50 | Non-gastric | |||

The debate in literature is still present regarding GI bleeding as a prognostic factor in case of GIST. Huang et al. in a retrospective cohort study explored whether GI bleeding could be a potential new indicator to predict the clinical behaviour and prognosis of GIST [15]. The Authors concluded that GI bleeding was an independent prognostic predictor of poor and shorter relapse-free survival (RFS) in GIST patients, especially those in high-risk groups, compared to non-GI-bleeding patients. Other Authors tried to demonstrate the relationship between GI bleeding and tumor rupture and found no correlation between the two [3,56]. Yin et al. in a 10-year retrospective study concluded that GI bleeding served with a surrogate for smaller GIST and was a protective factor for GIST relapse, therefore patients with GI bleeding achieved better prognosis [3]. Wan et al. in a propensity score matching analysis concluded that the group with GI bleeding had a superior RFS and overall survival compared to no GI bleeding group [56]. Both Authors attributed the results and the best possible outcome to earlier diagnosis and treatment as well as to smaller tumor size [3,56].

In view of the multiple aspects of GIST under consideration, its management requires a multidisciplinary approach [49].

4. Conclusions

Proximal jejunal GIST may cause both upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. In our opinion a multidisciplinary team approach is mandatory for the correct study and management of this disease and its complications. For a physician it is important to keep in mind the well-known association between NF1 and GIST, and to facilitate the diagnosis of an abdominal (bleeding) mass in a NF1 patient. In case of localised and resectable GIST surgical treatment is the mainstay. Laparoscopic approach is safe and effective if the oncological radicality is respected with negative resection margins and avoidance of tumor rupture.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Funding

The Authors declare no external funding and no sponsor involvement.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval exemption was given for this study.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Authors contribution

Stefano Mandalà M.D. designed this study and wrote this article. Antonino Mirabella M.D. contributed in designing the study. Massimo Lupo M.D., Marzio Guccione M.D., Camillo La Barbera M.D. and Dario Iadicola M.D. contributed in data collection and analysis.

Registration of research studies

Not Applicable.

Guarantor

Stefano Mandalà and Antonino Mirabella accept full responsibility for this work and the conduct of the study.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Zhou L., Liao Y., Wu J., Yang J., Zhang H., Wang X., Sun S. Small bowel gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a retrospective study of 32 cases at a single center and review of the literature. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2018;14:1467–1481. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S167248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim J.J., Lim J.Y., Nguyen S.Q. Laparoscopic resection of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Does laparoscopic surgery provide an adequate oncologic resection? World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2017;9(September (9)):448–455. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v9.i9.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yin Z., Gao J., Liu W., Huang C., Shuai X., Wang G., Tao K., Zhang P. Clinicopathological and prognostic analysis of primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor presenting with gastrointestinal bleeding: a 10-year retrospective study. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2017;21(May (5)):792–800. doi: 10.1007/s11605-017-3385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miettinen M., Lasota J. Histopathology of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J. Surg. Oncol. 2011;104(December (8)):865–873. doi: 10.1002/jso.21945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazur M.T., Clark H.B. Gastric stromal tumors. Reappraisal of histogenesis. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1983;7:507–519. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198309000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kindblom L.G., Remotti H.E., Aldenborg F., Meis-Kindblom J.M. Gastrointestinal pacemaker cell tumor (GIPACT): gastrointestinal stromal tumors show phenotypic characteristics of the interstitial cells of Cajal. Am. J. Pathol. 1998;152(May (5)):1259–1269. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joensuu H. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) Ann. Oncol. 2006;17(September (Suppl. 10)):x280–x286. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grassi N., Cipolla C., Torcivia A., Mandala S., Graceffa G., Bottino A., Latteri F. Gastrointestinal stromal tumour of the rectum: report of a case and review of literature. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008;14(February (8)):1302–1304. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrabi C., Mathew G., for the SCARE Group The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;84 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dualim D.M., Loo G.H., Rajan R., Nik Mahmood N.R.K. Jejunal GIST: hunting down an unusual cause of gastrointestinal bleed using double balloon enteroscopy. A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2019;60:303–306. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2019.06.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerson L.B., Fidler J.L., Cave D.R., Leighton J.A. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of small bowel bleeding. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015;110(September (9)):1265–1287. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.246. quiz 1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scarpa M., Bertin M., Ruffolo C., Polese L., D’Amico D.F., Angriman I. A systematic review on the clinical diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J. Surg. Oncol. 2008;98(October (5)):384–392. doi: 10.1002/jso.21120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gourgiotis S., Kotoulas D., Aloizos S., Kolovou A., Salemis N.S., Kantounakis I. Preoperative diagnosis of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding due to a GIST of the jejunum: a case report. Cases J. 2009;25(November (2)):9088. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-2-9088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khuri S., Gilshtein H., Darawshy A.A., Bahouth H., Kluger Y. Primary small bowel GIST presenting as a life-threatening emergency: a report of two cases. Case Rep. Surg. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/1814254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang Yuqian, Zhao Rui, Cui Yaping, Wang Yong, Xia Lin, Chen Yi, Zhou Yong, Wu Xiaoting. Effect of gastrointestinal bleeding on gastrointestinal stromal tumor patients: a retrospective cohort study. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018;24:363–369. doi: 10.12659/MSM.908186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tseng C.M., Lin I.C., Chang C.Y., Wang H.P., Chen C.C., Mo L.R., Lin J.T., Tai C.M.1. Role of computed tomography angiography on the management of overt obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. PLoS One. 2017;12(March (3)):e0172754. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto H., Yano T., Kita H. New system of double-balloon enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of small intestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1556. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen W.G., Shan G.D., Zhang H., Yang M., L L, Yue M., Chen W.G., Gu Q., Zhu H.T., Xu G.Q., Chen L.H. Double-balloon enteroscopy in small bowel diseases: eight years single-center experience in China. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(October (42)):e5104. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimazaki J., Tabuchi T., Nishida K., Takemura A., Kajiyama H., Motohashi G., Suzuki S. Emergency surgery for hemorrhagic shock caused by a gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the ileum: a case report. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2016;5(July (1)):103–106. doi: 10.3892/mco.2016.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Y.T., Sun H.L., Luo J.H., Ni J.Y., Chen D., Jiang X.Y., Zhou J.X., Xu L.F. Interventional digital subtraction angiography for small bowel gastrointestinal stromal tumors with bleeding. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014;20(December (47)):17955–17961. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i47.17955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gutmann D.H., Ferner R.E., Listernick R.H., Korf B.R., Wolters P.L., Johnson K.J. Neurofibromatosis type 1. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2017;23(February (3)):17004. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uusitalo E., Rantanen M., Kallionpää R.A., Pöyhönen M., Leppävirta J., Ylä-Outinen H., Riccardi V.M., Pukkala E., Pitkäniemi J., Peltonen S., Peltonen J. Distinctive cancer associations in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34(June (17)):1978–1986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.3576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ylä-Outinen H., Loponen N., Kallionpää R.A., Peltonen S., Peltonen J. Intestinal tumors in neurofibromatosis 1 with special reference to fatal gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 2019;7(September (9)):e927. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishida T., Tsujimoto M., Takahashi T., Hirota S., Blay J.Y., Wataya-Kaneda M. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in Japanese patients with neurofibromatosis type I. J. Gastroenterol. 2016;51(June (6)):571–578. doi: 10.1007/s00535-015-1132-6. Epub 2015 Oct 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salvi P.F., Lorenzon L., Caterino S., Antolino L., Antonelli M.S., Balducci G. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors associated with neurofibromatosis 1: a single centre experience and systematic review of the literature including 252 cases. Int. J. Surg. Oncol. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/398570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuller C.E., Williams G.T. Gastrointestinal manifestations of type 1 neurofibromatosis (von Recklinghausen’s disease) Histopathology. 1991;19(July (1)):1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1991.tb00888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miettinen M., Fetsch J.F., Sobin L.H., Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in patients with neurofibromatosis 1: a clinicopathologic and molecular genetic study of 45 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2006;30(January (1)):90–96. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000176433.81079.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mussi C., Schildhaus H.U., Gronchi A., Wardelmann E., Hohenberger P. Therapeutic consequences from molecular biology for gastrointestinal stromal tumor patients affected by neurofibromatosis type 1. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14(July (14)):4550–4555. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy A.D., Patel N., Abbott R.M., Dow N., Miettinen M., Sobin L.H. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in patients with neurofibromatosis: imaging features with clinicopathologic correlation. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2004;183(December (6)):1629–1636. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.6.01831629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han Sh, Park Sh, Cho Gh, Kim Nr, Oh Jh, Nam E., Shin D.B. Malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2007;22(March (1)):21–23. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2007.22.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saha S.B., Parmar R., Mandal A. Small bowel obstruction in a neurofibromatosis patient-a rare presentation of gastro-intestinal stromal tumors (GISTs): case report and literature review. Indian J. Surg. 2013;75(June (Suppl. 1)):415–417. doi: 10.1007/s12262-012-0746-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ESMO/European Sarcoma Network Working Group Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2014;25(September (Suppl. 3)):iii21–iii26. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen K., Zhang B., Liang Y.L., Ji L., Xia S.J., Pan Y., Zheng X.Y., Wang X.F., Cai X.J. Laparoscopic versus open resection of small bowel gastrointestinal stromal tumors: systematic review and meta-analysis. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 2017;130(July (13)):1595–1603. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.208249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou Y., Wang X., Si X., Wang S., Cai Z. Surgery for duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a systematic review and meta-analysis of pancreaticoduodenectomy versus local resection. Asian J. Surg. 2020;43(January (1)):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2019.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen Z., Chen P., Du N., Khadaroo P.A., Mao D., Gu L. Pancreaticoduodenectomy versus limited resection for duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Surg. 2019;19(August (1)):121. doi: 10.1186/s12893-019-0587-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Popivanov G., Tabakov M., Mantese G., Cirocchi R., Piccinini I., D’Andrea V., Covarelli P., Boselli C., Barberini F., Tabola R., Pietro U., Cavaliere D. Surgical treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the duodenum: a literature review. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018;21(September (3)):71. doi: 10.21037/tgh.2018.09.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee S.Y., Goh B.K., Sadot E., Rajeev R., Balachandran V.P., Gönen M., Kingham T.P., Allen P.J., D’Angelica M.I., Jarnagin W.R., Coit D., Wong W.K., Ong H.S., Chung A.Y., DeMatteo R.P. Surgical strategy and outcomes in duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2017;24(January (1)):202–210. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5565-9. Epub 2016 Sep 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Z., Zheng G., Liu J., Liu S., Xu G., Wang Q., Guo M., Lian X., Zhang H., Feng F. Clinicopathological features, surgical strategy and prognosis of duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a series of 300 patients. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(May (1)):563. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4485-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang Yi, Chen Guofeng, Lina Lele, Jin Xiaoli, Kang Muxing, Zhang Yaoyi, Shi Dike, Chen Kaibo, Guo Qingqu, Chen Li, Wu Dan, Huang Pintong, Chen Jian. Resection of GIST in the duodenum and proximal jejunum: a retrospective analysis of outcomes. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2019;45(October (10)):1950–1956. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2019.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koh Y.X., Chok A.Y., Zheng H.L., Tan C.S., Chow P.K., Wong W.K., Goh B.K. A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing laparoscopic versus open gastric resections for gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2013;20(October (11)):3549–3560. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liang J.W., Zheng Z.C., Zhang J.J., Zhang T., Zhao Y., Yang W., Liu Y.Q. Laparoscopic versus open gastric resections for gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a meta-analysis. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutan. Tech. 2013;23(August (4)):378–387. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31828e3e9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen K., Zhou Y.C., Mou Y.P., Xu X.W., Jin W.W., Ajoodhea H. Systematic review and meta-analysis of safety and efficacy of laparoscopic resection for gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach. Surg. Endosc. 2015;29(February (2)):355–367. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3676-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ihn K., Hyung W.J., Kim H.I., An J.Y., Kim J.W., Cheong J.H., Yoon D.S., Choi S.H., Noh S.H. Treatment results of small intestinal gastrointestinal stromal tumors less than 10 cm in diameter: a comparison between laparoscopy and open surgery. J. Gastric Cancer. 2012;12(December (4)):243–248. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2012.12.4.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cai W., Wang Z.T., Wu L., Zhong J., Zheng M.H. Laparoscopically assisted resections of small bowel stromal tumors are safe and effective. J. Dig. Dis. 2011;12(December (6)):443–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2011.00536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wan P., Li C., Yan M., Yan C., Zhu Z.G. Laparoscopy-assisted versus open surgery for gastrointestinal stromal tumors of jejunum and ileum: perioperative outcomes and long-term follow-up experience. Am. Surg. 2012;78(December (12)):1399–1404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hirota S., Isozaki K., Moriyama Y., Hashimoto K., Nishida T., Ishiguro S., Kawano K., Hanada M., Kurata A., Takeda M., Muhammad Tunio G., Matsuzawa Y., Kanakura Y., Shinomura Y., Kitamura Y. Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 1998;279(January (5350)):577–580. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heinrich M.C., Corless C.L., Duensing A., McGreevey L., Chen C.J., Joseph N., Singer S., Griffith D.J., Haley A., Town A., Demetri G.D., Fletcher C.D., Fletcher J.A. PDGFRA activating mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 2003;299(January (5607)) doi: 10.1126/science.1079666. 708-10.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Akahoshi K., Oya M., Koga T., Shiratsuchi Y. Current clinical management of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018;24(July (26)):2806–2817. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i26.2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanchez-Hidalgo J.M., Duran-Martinez M., Molero-Payan R., Rufian-Peña S., Arjona-Sanchez A., Casado-Adam A., Cosano-Alvarez A., Briceño-Delgado J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a multidisciplinary challenge. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018;24(May (18)):1925–1941. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i18.1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.von Mehren M., Joensuu H. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018;36(January (2)):136–143. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.9705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fletcher C.D., Berman J.J., Corless C., Gorstein F., Lasota J., Longley B.J., Miettinen M., O’Leary T.J., Remotti H., Rubin B.P., Shmookler B., Sobin L.H., Weiss S.W. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Hum. Pathol. 2002;33(May (5)):459–465. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.123545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miettinen M., Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: pathology and prognosis at different sites. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2006;23(May (2)):70–83. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Joensuu H. Risk stratification of patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Hum. Pathol. 2008;39(October (10)):1411–1419. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miettinen M., Makhlouf H., Sobin L.H., Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the jejunum and ileum: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 906 cases before imatinib with long-term follow-up. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2006;30(April (4)):477–489. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200604000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang Z., Wang F., Liu S., Guan W. Comparative clinical features and short-term outcomes of gastric and small intestinal gastrointestinal stromal tumours: a retrospective study. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(July (1)):10033. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46520-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wan W., Xiong Z., Zeng X., Yang W., Li C., Tang Y., Lin Y., Gao J., Zhang P., Tao K. The prognostic value of gastrointestinal bleeding in gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a propensity score matching analysis. Cancer Med. 2019;8(August (9)):4149–4158. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]