Abstract

At present, it has been noticed that some patients recovered from COVID-19 present a recurrent positive RNA test of SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) after being discharged from hospitals. The purpose of the current study was to characterize the clinical features of re-hospitalized patients with recurrent SARS-CoV-2 positive results. From January 12 to April 1 of 2020, our retrospective study was conducted in China. The exposure history, baseline data, laboratory findings, therapeutic schedule, and clinical endpoints of the patients were collected. All the patients were followed until April 10, 2020. Among all COVID-19 patients included in the current study, there were 14 re-hospitalized patients due to recurrent positive tests of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Fever (11 [78.6%]), cough (10 [71.4%]), and fatigue (7 [50.0%]) were the most common symptoms on the patient’s first admission, and less symptoms were found on their second admission. The average duration from the onset of symptoms to admission to hospital was found to be 8.4 days for the first admission and 2.6 days for the second admission (P = 0.002). The average time from the detection of RNA (+) to hospitalization was 1.9 days for the first admission and 2.6 days for the second admission (P = 0.479), and the average time from RNA (+) to RNA (−) was 11.1 days for the first admission and 6.3 days for the second admission (P = 0.030). Moreover, the total time in hospital was 18.6 days for the first admission and 8.0 days for the second admission (P = 0.000). It may be necessary to increase the isolation observation time and RT-PCR tests should be timely performed on multiple samples as soon as possible.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Re-hospitalization, Management, Outcome

Introduction

On Mar 14, 2020, the newly discovered severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) that induced coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which resulted in the present worldwide pandemic. COVID-19 is spreading around the world and threatening global health [5, 8]. Tillett et al. used genome sequencing to show that one patient could be infected by SARS-CoV-2 in two different occasions and found that the second infection of this patient had more severe symptoms than that in the first infection [15], which shows that reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 may challenge the efficacy of vaccines [6]. However, Cento et al. believed that a recurrent positive test of SARS-CoV-2 RNA did not mean of a transmissible virus in vivo [1]. The symptomatic patients with COVID-19 are supposed to be the main source of outbreak, but asymptomatic infections may be a potential troubling occurrence in the near future [10, 12, 20].

Asymptomatic infections were announced in the seventh edition of the guidelines from National Health Commission of China. In clinical practice, very few cured patients were detected with positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA even after discharging [7, 9, 18, 19]. A meta-analysis of 17 studies with 5182 COVID-19 patients reported a recurrence positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA rate of 12%. They believed that the respiratory tract samples should be repeated nucleic acid tests in both the first and second months after recovery from COVID-19 [13]. Follow-up observation of the baseline characteristics of these patients and whether family members are infected with SARS-CoV-2 may help to develop management strategies in targeting these groups. Here, we reported 14 re-hospitalized patients due to a recurrent positive result of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Further investigations of the clinical characteristics of such patients may contribute to the improvement of current criteria for release and reduction of recurrence rate.

Materials and methods

Study design

The study was performed in China from January 12 to April 1, 2020 and had been approved by the Ethics Committees of Huanggang Central Hospital (No. HGYY-2020-005) and Wuhan Union Hospital (No. 2020-0077-1). In total, 1350 patients with COVID-19 from the general wards and intensive care units (ICU) were initially enrolled in the current study.

The inclusion criteria were (1) diagnosis of COVID-19 was all confirmed by positive test of SARS-CoV-2 RNA from the throat swab or sputum samples according to WHO interim guidance; (2) criteria for all COVID-19 patients discharging from hospitals were based on the guidelines by National Health Commission of China: (i) normal temperature for at least 3 days, (ii) no obvious respiratory symptoms, (iii) significant absorption of lesions in chest computerized tomography (CT) scans, (iv) double check of negative SARS-CoV-2 RNA tests (sampling interval over 24h); (3) the patients were hospitalized no less than 2 times due to re-detectable positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA; (4) chest CT scans and blood tests were performed. Those patients who did not meet all of the criteria listed above were excluded from the current study.

Data collection

Each COVID-19 case report was carefully reviewed from electronic medical records. All the data were collected by two different co-authors independently. The exposure history, demographic data, baseline characteristics, laboratory data, therapeutic programs, and clinical endpoints, especially the RNA test of SARS-CoV-2, were extracted. The results of viral RNA were based on the first positive and the first valid negative data (i.e., the first negative result before reaching the discharge standard). In the present study, samples by throat swabs were obtained from the patients at the time of admission, and during the time of home or hotel quarantine were tested by real-time reverse transcription PCR [4].

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were shown as means (± standard deviation [SD]) or medians with interquartile range (IQR). Categorical data were described as percentages. All laboratory results were assessed if the measurements exceeded the normal level. A paired t test was used for continuous data and chi-squared test was applied to compare count data. A two-tailed P value less than 0.05 was selected as the cutoff value for statistical significance. SPSS version 20 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to conduct statistical analyses in the current study.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 1350 COVID-19 patients were selected as the initial study population from January 12 to April 1, 2020. Only 20 cases of COVID-19 were re-detected with positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Six patients who lack complete data were excluded. Finally, 14 cases met the inclusion criteria. The final follow-up was April 10, 2020.

Baseline characteristics of 14 patients on two admissions are summarized in Tables 1, 2, and Fig. 1. The average age of the patients was 44.4 years old (SD ± 15.0), with 10 males and 4 females. According to the epidemiological history, 7 (50.0%) patients remembered clearly about their history of exposure in the first admission and 14 (100.0%) patients in the second admission. Fever (11 [78.6%]), cough (10 [71.4%]), and fatigue (7 [50.0%]) were the most common symptoms, and digestive symptoms such as lack of appetite (4 [28.6%]) and diarrhea (1 [7.1%]) were reported on the first admission. However, except for one patient who had a cough, the remaining 13 patients had no symptoms on the second admission. Additionally, new lesions were not found in all patients undergoing chest CT on second admission. Meanwhile, most patients rarely had underlying comorbidities. On the first admission, there were 14 (100.0%) patients receiving antiviral drugs including lopinavir/ritonavir or arbidol, 11 (78.57%) receiving Lianhua Qingwen, and 8 (57.1%) receiving nebulized α-interferon treatment. Similarly, 10 (71.43%) patients on second hospitalization received antiviral treatment.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes of 14 re-hospitalized COVID-19 patients after recurrent positive test of SARS-CoV-2 RNA

| Characteristics | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | Case 7 | Case 8 | Case 9 | Case 10 | Case 11 | Case 12 | Case 13 | Case 14 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 1st | 2nd | 1st | 2nd | 1st | 2nd | 1st | 2nd | 1st | 2nd | 1st | 2nd | 1st | 2nd | 1st | 2nd | 1st | 2nd | 1st | 2nd | 1st | 2nd | 1st | 2nd | 1st | 2nd | |

| Age, years | 50 | 30 | 61 | 53 | 31 | 56 | 40 | 57 | 30 | 20 | 39 | 70 | 56 | 29 | ||||||||||||||

| Sex (M/F) | Female | Male | Male | Female | Male | Male | Male | Male | Female | Male | Male | Male | Male | Female | ||||||||||||||

| Disease condition | S | Mo | Mo | Mo | Mo | Mo | Mo | Mo | Mo | Mi | Mo | Mo | Mo | Mo | Mo | Mo | Mi | Mi | Mo | Mo | Mo | Mo | Mo | Mo | Mo | Mo | Mo | Mo |

| Respiratory rate | 21 | 18 | 20 | 18 | 22 | 22 | 20 | 22 | 20 | 21 | 25 | 19 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 21 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 18 | 20 | 26 | 20 | 20 | 22 | 20 | 21 | 20 |

| Time from onset of symptoms to admission | 8 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 18 | 2 | 10 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 14 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 21 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 9 |

| Time from onset of RNA (+) to admission | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 9 |

| Time from onset of RNA (+) to RNA (−) | 9 | 3 | 17 | 2 | 13 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 6 | 33 | 15 | 5 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 18 | 9 | 12 | 4 | 5 | 14 |

| Time from onset of RNA (−) to RNA (+) | 29 | 12 | 19 | 40 | 26 | 22 | 7 | 17 | 22 | 19 | 30 | 10 | 22 | 16 | ||||||||||||||

| Time from discharge to RNA (+) | 11 | 8 | 14 | 14 | 21 | 15 | 1 | 12 | 10 | 13 | 17 | 7 | 17 | 11 | ||||||||||||||

| Total days in hospital | 27 | 4 | 19 | 4 | 18 | 5 | 30 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 13 | 7 | 16 | 11 | 38 | 18 | 15 | 8 | 13 | 6 | 17 | 7 | 22 | 19 | 15 | 6 | 8 | 8 |

| Common symptoms | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fever | √ | × | × | × | √ | × | √ | × | √ | × | √ | × | √ | × | √ | × | √ | × | √ | × | √ | × | × | × | √ | × | × | × |

| Cough | √ | × | √ | × | × | × | √ | × | √ | × | √ | × | √ | × | √ | × | × | × | √ | × | √ | × | × | × | × | × | √ | √ |

| Short of breath | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | √ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| Diarrhea | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | √ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| Lack of appetite | √ | × | × | × | √ | × | √ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | √ | × | × | × | × | × |

| Weakness | √ | × | √ | × | × | × | √ | × | × | × | √ | × | √ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | √ | × | √ | × | × | × |

| Muscle pain | × | × | × | × | × | × | √ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | √ | × | √ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| Exposure history | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Clear exposure | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Unclear exposure | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Comorbidities | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Respiratory disease | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||||||||

| Gastrointestinal diseases | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||||||||

| Cardiovascular system disease | × | × | × | √ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||||||||

| Nervous system disease | √ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||||||||

| Endocrine system disease | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||||||||

| Malignant tumor | × | × | × | × | × | √ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||||||||

| Blood system diseases | × | × | × | √ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||||||||

| Treatments | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Antibiotic treatment | √ | × | × | × | √ | × | √ | × | × | × | √ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | √ | × | × | √ |

| Antifungal treatment | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| Antiviral treatment | √ | √ | √ | × | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | × | √ | √ | √ | × | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | × | √ | √ |

| Glucocorticoids | √ | × | × | × | √ | × | √ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | √ | × | × | × |

| Nebulized IFN-α | √ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | √ | × | √ | × | √ | × | × | √ | √ | √ | × | × | √ | × | × | × | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Immunoglobulin | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | √ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | √ | × | × | × |

| Lianhua Qingwen | √ | × | √ | √ | √ | × | √ | × | √ | × | √ | × | √ | × | √ | √ | × | × | √ | √ | √ | × | × | × | √ | × | × | × |

S severe, Mo moderate, Mi mild, IFN-α α-interferon

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes of COVID-19 patients between two admissions

| Characteristics | All patients (n = 14) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First admission (n = 14) | Second admission (n = 14) | ||

| Age, years [mean (SD)] | 44.4 ± 15.0 | / | |

| Sex (M/F) | (10/4) | ||

| Respiratory rate | 20.9 ± 1.4 | 20.4 ± 2.1 | 0.530 |

| Days from onset of symptoms to admission | 8.4 ± 5.5 | 2.6 ± 2.2 | 0.002 |

| Days from onset of RNA (+) to admission | 1.9 ± 1.6 | 2.6 ± 2.2 | 0.479 |

| Days from onset of RNA (+) to RNA (−) | 11.1 ± 7.7 | 6.3 ± 4.0 | 0.030 |

| Days from onset of RNA (−) to RNA (+) | 20.8 ± 8.7 | / | |

| Days from discharge to RNA (+) | 12.2 ± 4.9 | / | |

| Total days in hospital | 18.6 ± 8.3 | 8.0 ± 4.9 | 0.000 |

| Common symptoms | |||

| Fever | 11 (78.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.003 |

| Cough | 10 (71.4%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0.008 |

| Short of breath | 1 (7.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.999 |

| Diarrhea | 1 (7.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.999 |

| Lack of appetite | 4 (28.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.134 |

| Fatigue | 7 (50.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.023 |

| Muscle pain | 3 (21.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.249 |

| Epidemiological history | |||

| Clear contact history | 7 (50.0%) | 14 (100.0%) | 0.023 |

| Unclear contact history | 7 (50.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.023 |

| Medical treatment after admission | |||

| Antibiotic treatment | 5 (35.7%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0.221 |

| Antifungal treatment | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Antiviral treatment | 14 (100.0%) | 10 (71.4%) | 0.134 |

| Glucocorticoids | 4 (28.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.134 |

| Nebulized α-interferon treatment | 8 (57.1%) | 4 (28.6%) | 0.134 |

| Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy | 2 (14.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.480 |

| Lianhua Qingwen | 11 (78.6%) | 3 (21.4%) | 0.013 |

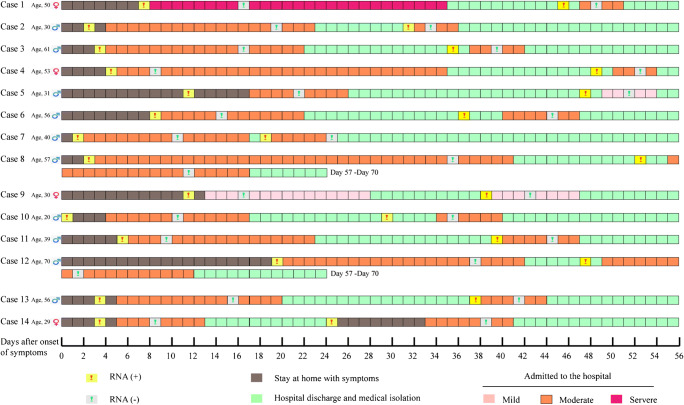

Fig. 1.

The admission and discharge history of 14 re-hospitalized COVID-19 patients after recurrent positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA

RNA test outcomes of SARS-CoV-2

The results of SARS-CoV-2 RNA are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 1. In detail, the average time from detection of RNA (+) to hospital admission was 1.9 days (SD ± 1.6) for the first admission and 2.6 days (SD ± 2.2) for the second admission (P = 0.479). The average time from RNA (+) to RNA (−) was 11.1 days (SD ± 7.7) for the first admission and 6.3 days (SD ± 4.0) for the second admission (P = 0.030). The average time from onset of RNA (−) to RNA (+) was 20.8 days (SD ± 8.7) and the range of days from onset of RNA (−) to RNA (+) were 7 to 40 days for these patients. The average time from discharge to RNA (+) was 12.2 days (SD ± 4.9) and the days ranged from 1 to 21 days. Of the 14 cases, 4 (28.6%) patients had more than 14 days from discharge until recurrent positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Moreover, the average time from onset of symptoms to admission was 8.4 days (SD ± 5.5) for the first admission and 2.6 days (SD ± 2.2) for the second admission (P = 0.002). Additionally, the total time in hospital was 18.6 days (SD ± 8.3) for the first admission and 8.0 days (SD ± 4.9) for the second admission (P = 0.000).

Laboratory findings

Table 3 shows the details of laboratory data for two admitted in patients with COVID-19. White blood cell counts were 4.4 × 109/L (SD ± 1.8) on the first admission and 5.8 × 109/L (SD ± 1.4) on the second admission (P = 0.013), which may be a result of the increased lymphocyte and monocyte on the second admission (P = 0.000, 0.014). Platelet counts were 175.4 × 109/L (SD ± 42.6) on the first admission and 207.6 × 109/L (SD ± 46.7) on the second admission (P = 0.016). Moreover, several endpoints including prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, aspartate aminotransferase, and creatinine were significantly lower on the second admission than on the first admission (all P < 0.05). However, the significance of these changes is still unclear. There were no significant differences in other lab data for the second admissions.

Table 3.

Laboratory findings of patients with COVID-19 between two admissions

| Characteristics | All patients (n = 14) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First admission (n = 14) | Second admission (n = 14) | ||

| White blood cell count, × 109/L | 4.4 ± 1.8 | 5.8 ± 1.4 | 0.013 |

| Neutrophil count, × 109/L | 2.9 ± 1.3 | 3.6 ± 1.0 | 0.119 |

| Red blood cell count, × 109/L | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 0.103 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 137.9 ± 16.1 | 134.1 ± 22.3 | 0.318 |

| Neutrophil ratio, % | 65.1 ± 9.8 | 61.2 ± 6.0 | 0.214 |

| Lymphocyte count, × 109/L | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 0.000 |

| Lymphocyte ratio, % | 26.3 ± 8.3 | 28.5 ± 5.1 | 0.353 |

| Monocyte count, × 109/L | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.014 |

| Platelet count, × 109/L | 175.4 ± 42.6 | 207.6 ± 46.7 | 0.016 |

| Prothrombin time, s | 12.1 ± 1.0 | 11.2 ± 1.2 | 0.003 |

| Prothrombin activity, % | 109.3 ± 22.2 | 109.4 ± 18.1 | 0.653 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time, s | 32.8 ± 4.7 | 31.0 ± 2.8 | 0.049 |

| Fibrinogen, g/L | 4.1 ± 1.3 | 3.5 ± 0.8 | 0.098 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 25.8 ± 22.7 | 33.79 ± 25.6 | 0.162 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | 25.7 ± 9.7 | 21.8 ± 9.6 | 0.029 |

| Total bilirubin, mmol/L | 14.3 ± 9.1 | 16.2 ± 9.4 | 0.352 |

| Albumin, g/L | 41.1 ± 5.7 | 41.4 ± 3.8 | 0.930 |

| Blood nitrogen, mmol/L | 4.4 ± 1.6 | 4.6 ± 0.9 | 0.626 |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 83.2 ± 19.8 | 68.6 ± 13.3 | 0.014 |

| Fasting blood glucose, mmol/L | 5.2 ± 0.9 | 5.2 ± 0.6 | 0.946 |

Discussion

Fourteen COVID-19 patients with recurrent positive test of viral RNA after hospital discharging or termination of quarantine in Hubei, China (without clinical symptoms and radiological abnormalities and with two consecutive negative viral RNA test results over 24 h interval), were characterized in the present study. All these patients had positive test in 7–40 days since RNA (−), without any aggravation on symptoms and chest CT. Despite the fact that the incidence of recurrent SARS-CoV-2 positive results in recovered patients is low, this group of patients should be tested timely for many times.

Till now, the asymptomatic patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection could be a new source of transmission, which would bring some new infectious disease prevention and control issues [11, 14]. In general, these recurrent cases are characterized as asymptomatic viral carriers, but they are different from the “true” first diagnostic asymptomatic patient. These patients were previously diagnosed with COVID-19 and were discharged after standard treatment to meet the criteria for discharging. Moreover, it is important to note that people who had close contact with these recurrent cases were not found to have signs of COVID-19 infection. From this point of view, the management strategy for these recurrence cases is mainly isolation and observation. Our results suggested that antiviral therapy may not be a necessary treatment and that personalized treatment should be adopted for COVID-19 patients with recurrent positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA.

The underlying mechanisms of fluctuated SARS-CoV-2 RNA results are worth investigating. According to our results, all the 14 COVID-19 patients reported here with recurrent positive test of SARS-CoV-2 RNA had very clear history of a known exposure before their second admission and were related to the re-infection [21], which may explain the recurrence. Besides, real time-PCR assays with respiratory samples are considered as the reference standard for the diagnosis of COVID-19 [2]. As angiotensin converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2) is the host cell receptor for SARS-CoV-2 and is more easily spread in the lungs, the SARS-CoV-2 results may be false negative in nose or throat swab samples [3, 17], due to the lower viral load in these sites. Therefore, point-of-care technologies and serologic immunoassays may be a useful detection method [2]. Moreover, the proficiency of the operators and the accuracy of the kits are also important factors affecting the SARS-CoV-2 RNA results and can result in a false-negative RT-PCR result for detection of the virus [16]. What is more, the interval between two negative RT-PCR tests may not be sufficient to evaluate the degree of virus clearance. Before the second infection, further investigation is necessary to clarify pre-existing immune responses and viral load [6]. Viral load should be given more consideration as it is the most reliable method in determining whether it is safe for the patient to return to society [1].

In view of the possibility that the RT-PCR test results of the patients under the current criteria for hospital release from quarantine may convert to positive, some measures can be put in place to improve the current criteria and reduce the recurrence rate. Firstly, all the discharged patients are currently suggested to self-quarantine in their houses for 14 days according to China’s National Health Commission. However, our results indicated that the range of days from discharge to RNA (+) were 1 to 21 days, and 4 (28.6%) patients had more than 14 days from discharge to recurrent positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Mao et al. found that after a 14-day isolation, asymptomatic COVID-19 patients could be a source of viral transmission and proposes a challenge to self-quarantine [12]. Therefore, we believe that it may be more appropriate to recommend 3 weeks of self-quarantine for COVID-19 patients after discharge, who were performed RT-PCR test as soon as possible. Secondly, a longer interval, such as 48 h, between two consecutive negative results in the criteria for discharging from hospitals or the termination of the quarantine may be feasible to ensure that the patients to be discharged are not contagious and are less likely to have a recurrent positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Additionally, some laboratory examinations such as the absolute white blood cell as well as lymphocyte counts could be combined with the RT-PCR results as the criteria for hospital discharge to assure that the patients have completely recovered. Moreover, as SARS-CoV-2 RNA could be detected from sputum, throat swab, blood, or stool swab samples, multiple tests of different samples can be helpful in improving sensitivity. The test from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid specimen could be more reliable; however, a higher risk of exposure might occur. Finally, there is still no strong evidence of the contagious period of SARS-CoV-2 and the sample size was limited, and further studies will be needed to reduce the recurrence rate.

Limitations in the current study should be noted. Firstly, several missing data or even failure to follow-up can affect the accuracy of a patient’s identification. Therefore, selection bias is hard to avoid and might occur for the retrospective study, and further prospective studies are needed. Second, our results were mainly based on two hospitals, and a large-scale multicenter study will be needed to pay more attention to the interesting topic in future. Last but not least, because of the lack of genome sequencing, we are unable to confirm that the positive test results in the re-hospitalized patients were due to the relapse of the same viral strain or reinfection with a new strain. In future research, we will try genome sequencing to help us identify whether the disease is due to reinfection or a relapse.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the incidence of recurrent positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA test in the patients with COVID-19 after discharge is relatively low and these patients have virtually no symptoms. However, considering the possible potential infectivity, we believe that the current national guidelines may need to be further revised, especially those with recurrent positive results of SARS-CoV-2 RNA test. Furthermore, it could be particularly necessary to increase the isolation observation time and RT-PCR tests should be timely performed on multiple samples as soon as possible. Additionally, we should pay more attention to genome sequencing in order to identify whether the patient is reinfected or relapsed. Considering the patients’ underlying disease, personalized treatment should be taken to treat recurrent positive patients with COVID-19.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the patients included in the current study. All co-authors sincerely appreciate all the medical staffs who assisted Hubei and fought in the front line. We also thank Troy Gharibani (University of Maryland, USA) for improving the manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

LP, LT, GX, KW, and XW conceptualized the manuscript and edited subsequent versions. LP, RW, NY, and CH wrote the first draft. JY, XZ, TW, JH, FG, TL, JW, XL, MM, and WH collected and analyzed data. YG and CL contributed ideas on the texts. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Technology Plan Project of Binzhou Medical University (CN, BY2017KJ30), Health and Family Planning Commission of Shandong Province (CN, 2017WS366), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (CN, 81700490).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its tables and figures].

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

The study had been approved by the Ethics Committees of Huanggang Central Hospital (No. HGYY-2020-005) and Wuhan Union Hospital (No. 2020-0077-1).

Consent to participate

Exemption.

Consent for publication

The participant has consented to the submission of this article to the journal. We confirm that the manuscript, or part of it, has neither been published nor is currently under consideration for publication. This work and the manuscript were approved by all co-authors.

Code availability

SPSS version 20 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lei Pan, Runsheng Wang, Na Yu, Chao Hu contributed equally to this work. They are listed as co-first authors. Xiaozhi Wang, Lei Tu, Kun Wan and Guogang Xu are listed as co-corresponding authors.

Contributor Information

Xiaozhi Wang, Email: bzyxy3013@163.com.

Lei Tu, Email: tulei_1985@126.com.

Kun Wan, Email: 301wk@sina.com.

Guogang Xu, Email: guogang_xu@163.com.

References

- 1.Cento V, Colagrossi L, Nava A, Lamberti A, Senatore S, Travi G, et al. Persistent positivity and fluctuations of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in clinically-recovered COVID-19 patients. J Infect. 2020;81:e90–e92. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng MP, Papenburg J, Desjardins M, Kanjilal S, Quach C, Libman M et al (2020) Diagnostic testing for severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus-2: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 10.7326/M20-1301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Feng H, Liu Y, Lv M, Zhong J (2020) A case report of COVID-19 with false negative RT-PCR test: necessity of chest CT. Jpn J Radiol. 10.1007/s11604-020-00967-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hui DS, E, I. A., Madani, T. A., Ntoumi, F., Kock, R., Dar, O., et al. The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health - the latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;91:264–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwasaki A (2020) What reinfections mean for COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30783-0

- 7.Jiang DM (2020) Recurrent PCR positivity after hospital discharge of people with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Infect. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Khot WY, Nadkar MY. The 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak - a global threat. J Assoc Physicians India. 2020;68:67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lan L, Xu D, Ye G, Xia C, Wang S, Li Y et al (2020) Positive RT-PCR test results in patients recovered from COVID-19. JAMA. 10.1001/jama.2020.2783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Li C, Ji F, Wang L, Wang L, Hao J, Dai M et al (2020) Asymptomatic and human-to-human transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in a 2-family cluster, Xuzhou. China. Emerg Infect Dis 26. 10.3201/eid2607.200718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Ling Z, Xu X, Gan Q, Zhang L, Luo L, Tang X, et al. Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infected patients with persistent negative CT findings. Eur J Radiol. 2020;126:108956. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2020.108956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mao ZQ, Wan R, He LY, Hu YC, Chen W (2020) The enlightenment from two cases of asymptomatic infection with SARS-CoV-2: is it safe after 14 days of isolation? Int J Infect Dis. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Mattiuzzi C, Henry BM, Sanchis-Gomar F, Lippi G. SARS-CoV-2 recurrent RNA positivity after recovering from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a meta-analysis. Acta Biomed. 2020;91:e2020014. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i3.10303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qian G, Yang N, Ma AHY, Wang L, Li G, Chen X et al (2020) A COVID-19 Transmission within a family cluster by presymptomatic infectors in China. Clin Infect Dis. 10.1093/cid/ciaa316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Tillett RL, Sevinsky JR, Hartley PD, Kerwin H, Crawford N, Gorzalski A et al (2020) Genomic evidence for reinfection with SARS-CoV-2: a case study. Lancet Infect Dis. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30764-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Xiao AT, Tong YX, Zhang S (2020) False-negative of RT-PCR and prolonged nucleic acid conversion in COVID-19: rather than recurrence. J Med Virol. 10.1002/jmv.25855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Xie C, Lu J, Wu D, Zhang L, Zhao H, Rao B et al (2020) False negative rate of COVID-19 is eliminated by using nasal swab test. Travel Med Infect Dis 101668. 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Xu Y, Li X, Zhu B, Liang H, Fang C, Gong Y, et al. Characteristics of pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infection and potential evidence for persistent fecal viral shedding. Nat Med. 2020;26:502–505. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0817-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan J, Kou S, Liang Y, Zeng J, Pan Y, Liu L (2020) PCR assays turned positive in 25 discharged COVID-19 patients. Clin Infect Dis. 10.1093/cid/ciaa398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Zhang J, Tian S, Lou J, Chen Y. Familial cluster of COVID-19 infection from an asymptomatic. Crit Care. 2020;24:119. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2817-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou L, Liu K, Liu HG. Cause analysis and treatment strategies of "recurrence" with novel coronavirus pneumonia (covid-19) patients after discharge from hospital. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2020;43:E028. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112147-20200229-00219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its tables and figures].