Abstract

During autophagy the enzyme Atg3 catalyzes the covalent conjugation of LC3 to the amino group of phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) lipids, which is one of the key steps in autophagosome formation. Here, we have demonstrated that an N-terminal conserved region of human Atg3 (hAtg3) communicates information from the N-terminal membrane curvature-sensitive amphipathic helix (AH), which presumably targets the enzyme to the tip of phagophore, to the C-terminally located catalytic core for LC3–PE conjugation. Mutations in the putative communication region greatly reduce or abolish the ability of hAtg3 to catalyze this conjugation in vitro and in vivo, and alter the membrane-bound conformation of the wild-type protein, as reported by NMR. Collectively, our results demonstrate that the N-terminal conserved region of hAtg3 works in concert with its geometry-selective AH to promote LC3–PE conjugation only on the target membrane, and substantiate the concept that highly curved membranes drive spatial regulation of the autophagosome biogenesis during autophagy.

Subject terms: Enzymes, Solution-state NMR, Biophysics

The E2-like enzyme human Atg3 catalyses the transfer of ubiquitin-like mammalian LC3 to the lipid phosphatidylethanolamine during autophagosome formation. Here, the authors combine NMR measurements with in vitro biochemical and in vivo cellular assays and show that the N-terminal conserved region of human Atg3 communicates information from the curvature-sensing domain to its active site.

Introduction

Macroautophagy (autophagy) is a highly conserved stress response in eukaryotes1–3. The process begins with the assembly of the phagophore (a cup-shaped vesicle), which, in turn, undergoes membrane expansion via a largely unknown mechanism and eventually seals to form the autophagosome (a double-membrane organelle). Formation of this organelle results in encapsulation of its cargo for degradation following fusion with the lysosome. The entire process requires the coordination of more than 30 autophagy-related (Atg) proteins in a spatially and temporally controlled manner4–6. The hallmark of the autophagosomal membrane is the covalent attachment of LC3, one of the homologs of yeast Atg8, directly to the amino group of phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) lipids in the membrane resulting in the LC3–PE complex (also referred as LC3-II)7. The conjugation of LC3 to PE lipids proceeds in three sequential steps: first, the cysteine protease Atg4 removes the last (or a few) C-terminal residue of LC3; second, Atg7, an E1-like activating enzyme, activates LC3 and catalyzes the formation of a thioester intermediate (LC3-Atg3) with an E2-like enzyme Atg3; third, the Atg5–Atg12/Atg16 complex, a presumed E3-like enzyme, promotes the transfer of LC3 from LC3-Atg3 to PE. The formation of LC3–PE triggers phagophore expansion and acts as an adaptor for sequestering cargos for breakdown7,8.

The structures of yeast and Arabidopsis thaliana Atg3 homologs reveal a catalytic core with structural and presumably mechanistic similarity to members of the E2 ligase family, despite having little sequence similarity2,9–11. In vivo, Atg3 functions in concert with the Atg12–Atg5/Atg16 complex, which is thought to allosterically activate Atg3 for conjugation of LC3 to PE in membranes12,13. However, in vitro, Atg3 alone can catalyze the conjugation, although the addition of the Atg12–Atg5/Atg16 complex increases activity. Targeting Atg3 to the membranes containing PE substrates requires its N-terminus, which seemingly is not part of the more C-terminally located catalytic core. Removal of the first 3 residues of yeast Atg3 (yAtg3) results in an enzyme with reduced activity, and deletion of the first 7 residues abolishes Atg8–PE conjugation14. It has been suggested that residues 3–13 form an amphipathic helix (AH) that targets the enzyme to the membrane, since disrupting the hydrophobic face, or swapping the equatorial charged residues, severely reduces Atg8–PE conjugation in vivo and in vitro14. Furthermore, the corresponding putative AH region of mouse Atg3 (mAtg3) has recently been shown to be responsible for its membrane curvature-dependent conjugation activity; the catalytic activity of mAtg3 for LC3–PE formation markedly increases as the size of liposomes decreases below 50 nm15,16. This has led to the suggestion that the N-terminal AH guides the enzyme to the leading edge of an expanding phagophore, where the membrane is highly curved with a radius possibly as small as 10 nm17. Here, we demonstrate that the N-terminus is not merely a membrane curvature-selective anchor; membrane binding, while necessary, is not sufficient for catalyzing LC3–PE conjugation.

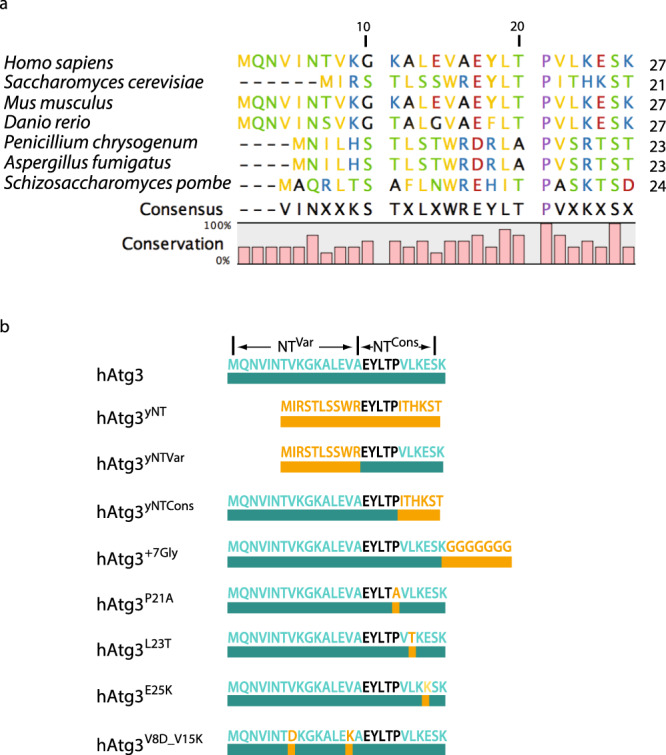

Sequence analysis of the Atg3 N-terminus from multiple species reveals a highly conserved region extending from residues 17 to 26 of hAtg3 (Fig. 1a). This region includes the last three resides of the N-terminal AH (residues 3–19), and the corresponding region in the yeast and A. thaliana homologs is not observed in existing crystal structures. We discovered that this conserved region plays a previously undescribed role in linking the membrane curvature-sensing role of the AH to its PE conjugase activity. Using LC3B, a mammalian homolog of yeast Atg8, we show that mutations in this region greatly reduce or abolish LC3B–PE conjugations in the in vitro and in vivo assays, despite retaining normal liposome binding and formation of the thioester LC3B-hAtg3 intermediate. NMR chemical shift perturbation (CSP) experiments indicate that structural rearrangements in the C-terminal part of hAtg3 (including the active site) occur upon the binding of its N-terminal AH to the membrane, and that the conserved region is critical for inducing these functionally relevant structural changes. Together, our results support the hypothesis that tight coordination of the membrane curvature-sensitive interaction of hAtg3 with its LC3–PE catalytic activity helps ensure that the biogenesis of the autophagosome proceeds in a spatially regulated manner.

Fig. 1. The N-terminals (NTs) of Atg3 homology have variable and conserved regions.

a Sequence analysis of Atg3 from multiple species, as well as the consensus sequence. All sequences begin at the first residue of the protein; residues numbered at the top refer to the human sequence. Non-polar and aromatic residues are in yellow, polar residues in green, positively charged and histidine residues in blue, negatively charged residues in red, alanine and glycine residues in black, and proline residue in purple. b Diagrams of hAtg3 NT constructs prepared in this study. Sequences corresponding to the hAtg3 sequence are teal and mutations and insertions are gold.

Results

Sequence analysis reveals conserved and variable regions in Atg3’s N-terminus

Figure 1a displays the sequence alignment of the 27 residues of the N-terminal of hAtg3 (herein referred to as NT), which are unstructured in aqueous solution, to the analogous region in selected organisms. Despite the fact that the NT is essential for protein activity, this region sharply diverges in sequence identity and length, with fungi tending to have shorter helices and more large hydrophobic residues compared to other kingdoms (however, all animal forms share high homology, Supplementary Fig. 1). The observed sequence alignments also suggest that the NT region can be divided into two sub-regions (Fig. 1a): a variable region (residues 1–16 of hAtg3, NTVar) and a conserved region (residues 17–26 of hAtg3, NTCons) which includes a highly conserved sequence motif (EYLTP). These differences are best illustrated by comparing the NTs of Homo sapiens and Saccharomyces cerevisiae Atg3. The yeast variable region is shorter than that seen in humans and contains a more hydrophobic set of residues, while the conserved region shares noticeable homology with the human Atg3. The NTVar region makes up most of hAtg3 AH (residues 3–19, defined by our NMR study described below) which is responsible for the protein’s membrane curvature-dependent binding, but a functional role of the NTCons has not yet been reported. In the following studies, we examine the roles of NTCons in membrane binding, formation of the thioester LC3B-hAtg3 intermediate, and LC3B–PE conjugation, using established in vitro and in vivo assays17 and NMR.

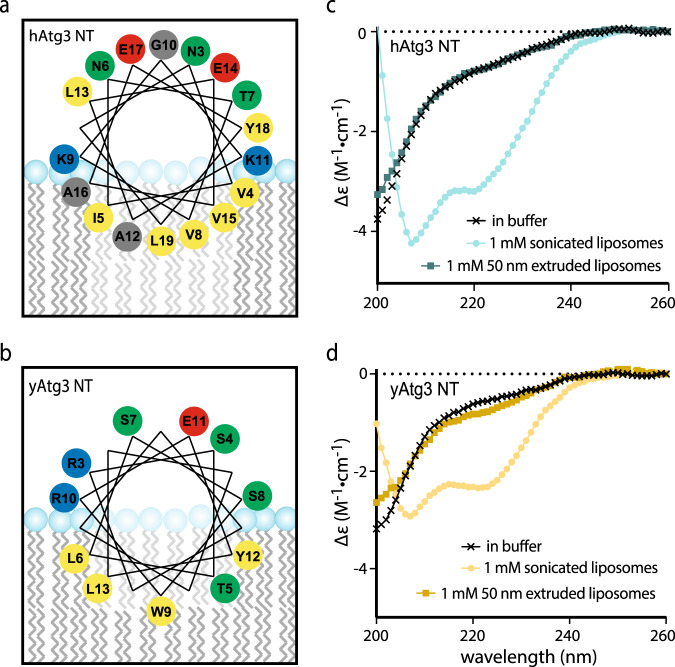

We first determined whether the NTVar of yAtg3 has membrane curvature-sensing properties, since it shares poor sequence similarity with hAtg3’s NTVar. Helical wheel plots for both NTs up to the conserved Leu19 display quite different chemical characteristics (Fig. 2a, b). The polar face of the hAtg3 AH contains multiple charges including two equatorial lysines, while its non-polar face is rich in hydrophobic amino acids with small side chains such as valine and alanine. However, the polar face of the yAtg3 AH is rich in serines and threonines and its non-polar face has large hydrophobic residues such as tryptophan and leucine. This pattern of residues is a characteristic feature of an ALPS (amphipathic lipid packing sensor) motif18. To determine whether both AHs demonstrate similar membrane curvature-sensing behavior, we synthesized two peptides that correspond to the sequences of the NT regions of hAtg3 and yAtg3 (Fig. 1a) and examined their secondary structure in the presence and absence of lipid vesicles of different sizes using circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. Both peptides showed the spectral features of a random coil in aqueous solution (Fig. 2c, d). This is consistent with the behavior of typical AH peptides. In the presence of sonicated liposomes (average sizes of 32 nm measured by dynamic light scattering) but not 50 nm extruded liposomes (average sizes of 56 nm measured by dynamic light scattering), the CD spectra of both were more representative of that expected for α-helical peptides. Furthermore, the observed coil to helix transition requires the presence of negatively charged lipids in liposomes16 but is not sensitive to exact lipid composition and PE is not essential (Supplementary Fig. 2). This indicates that the membrane curvature sensitivity of Atg3’s AH is conserved among homologs, likely through different curvature-sensing mechanisms because of their lack of sequence conservation18,19.

Fig. 2. Atg3 NTs have conserved membrane curvature sensitivity.

a, b Helical wheel plots for hAtg3 and yAtg3 amphipathic helix. Residues are colored as in Fig. 1a. c, d CD spectra of hAtg3 NT and yAtg3 NT, respectively, in the absence and presence of 10% DOPG, 90% POPC sonicated, and 50 nm extruded liposomes. Average sizes for sonicated and 50 nm extruded liposomes, measured by dynamic light scattering, are 32 and 56 nm, respectively.

The NTCons of hAtg3’s NT is key to its activity

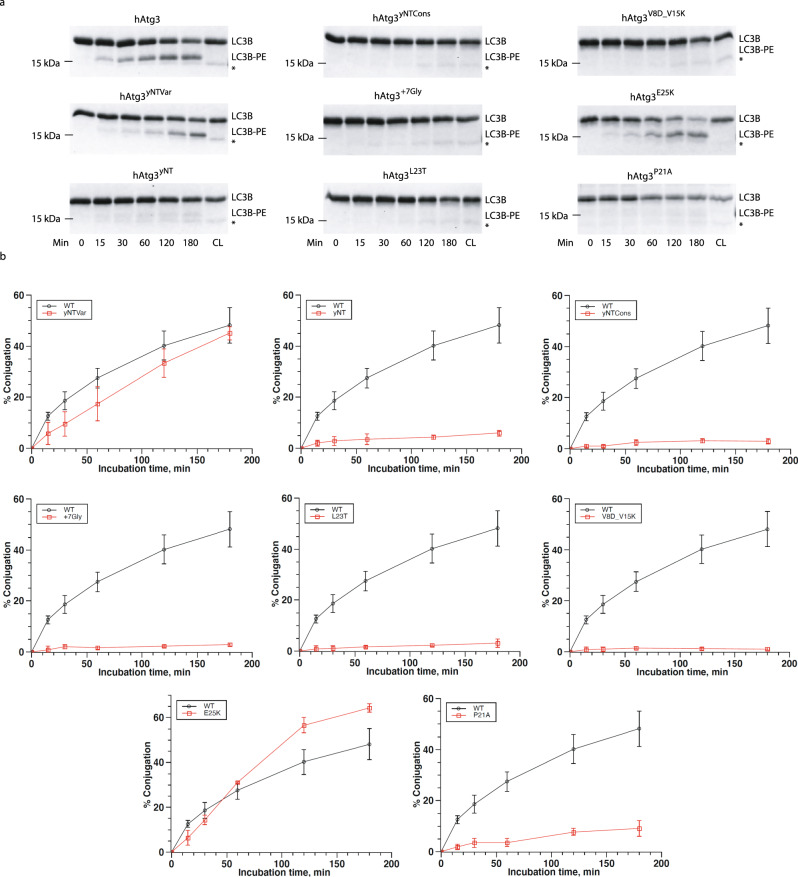

Capitalizing on the fact that the AH region of NTs, as a whole, shows conserved membrane curvature sensitivity, we prepared three chimeric constructs to investigate the functional significance of the hAtg3’s NTCons region: hAtg3yNTVar, hAtg3yNTCons, and hAtg3yNT (replacing the NT’s variable region, conserved region, and the entire NT of hAtg3 with that of yAtg3, respectively, Fig. 1b). In the in vitro conjugation assay, hAtg3yNTvar retained about 90% of the wild-type activity (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 3a), suggesting that the curvature-sensing region of yAtg3’s NT is capable of directing the chimeric proteins to the targeted membrane, as expected from our peptide study. Surprisingly, hAtg3yNTCons and hAtg3yNT effectively abolish LC3B–PE conjugation (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 3a). In order to investigate whether the spatial arrangement of the NTCons region to the rest of protein is important, we designed a mutant with a linker of seven Gly residues inserted between residues Lys27 and Phe28 (hAtg3+7Gly). We reasoned that this flexible linker presumably would “decouple” the membrane binding activity of hAtg3 AH from its conjugase activity. In the in vitro conjugation assay hAtg3+7Gly shows little activity (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 3a). These results suggest that the NTCons region plays a critical role in enzyme activity.

Fig. 3. The N-terminal conserved region of hAtg3 is critical for protein function.

a SDS-PAGE gel images of time-dependent formation of LC3B–PE for hAtg3, hAtg3yNTVar, hAtg3yNT, hAtg3yNTCons, hAtg+7Gly, and for hAtg3P21A, hAtg3L23T, hAtg3E25K as well as hAtg3V8D_V15K. Gels were quantified with ImageJ; conjugation percentage of LC3B–PE was determined by the amount of LC3B–PE divided by the total LC3B present. CL is the control without liposomes. * Asterisk indicates a small amount of degradation of LC3B in the presence of ATP. b Plots of time-dependent formation of LC3B–PE for hAtg3 and mutants. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Quantification of conjugation reactions were obtained from three separate measurements (n = 3).

To examine whether specific residues in the NTCons region are important for LC3B–PE conjugation, we constructed three variant forms: hAtg3L23T, hAtg3E25K, and hAtg3P21A (Fig. 1b). The first two (hAtg3L23T and hAtg3E25K) substitute residues that differ most in their side chain properties between the human and yeast NTCons regions and may account for the inability of the hAtg3yNTCons and hAtg3yNT to support LC3B–PE conjugation. The third substitution (hAtg3P21A) replaces an invariant proline residue with an alanine. It was chosen because proline has been shown to perform a critical role in membrane curvature-sensing AHs20. In the in vitro conjugation assay, hAtg3E25K produces about 30% more LC3B–PE than the wild-type protein does after 2 h, but hAtg3L23T and hAtg3P21A have severely reduced conjugation activity in vitro (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 3a). The results of CD and liposome co-sedimentation assays21,22 allow us to rule out the possibility that a defect in protein–membrane interactions is a major contributor to the effects of these substitutions. All mutants interact with the liposomes in an analogous manner to wild-type protein except that the binding of hAtg3L23T is reduced by about 40% (Supplementary Figs. 4a, b and 5). As a control, we also examined the AH folding and liposome binding of hAtg3V8D_V15K, a mutant designed not to interact with the membrane15. As expected, the NTV8D_V15K peptide is unfolded in the presence of liposomes and the hAtg3V8D_V15K protein shows minimal levels of liposome association (Supplementary Figs. 4c and 5), which is similar to an hAtg3 construct without the first 25 residues. Furthermore, all variants can form a normal covalent thioester intermediate with LC3B (Supplementary Fig. 3b), indicating that these mutations do not affect their interactions with the E1-like Atg7. Together, these results indicate that the binding of AH to the membrane is necessary but not sufficient to promote the LC3B–PE conjugation, and functional forms of both the AH and the NTCons region of hAtg3 are required in vitro.

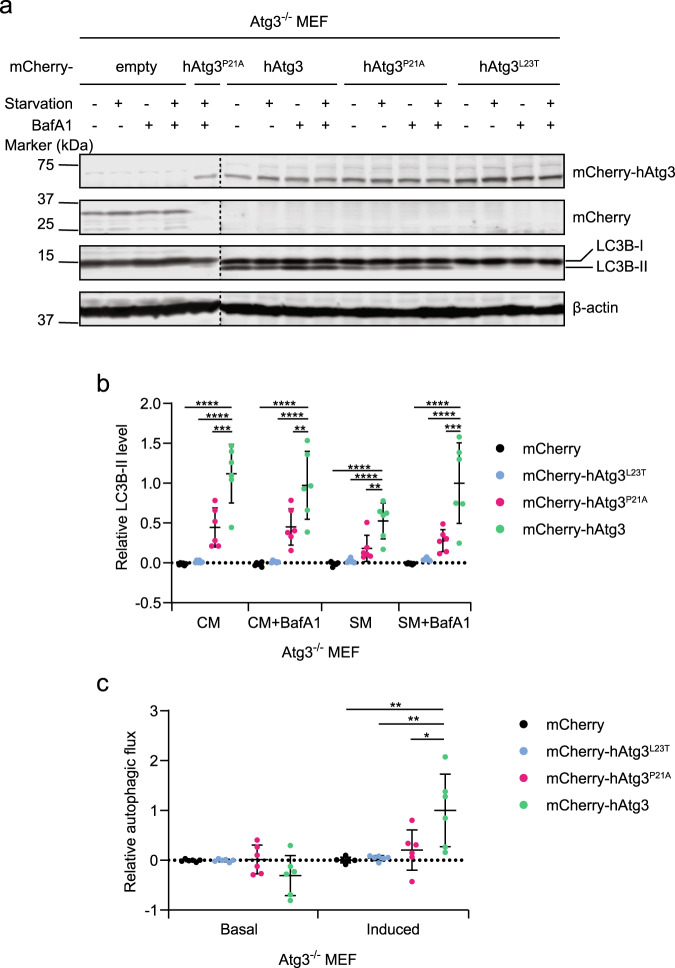

hAtg3P21A and hAtg3L23T mutants do not restore LC3B lipidation and autophagic flux in Atg3 knockout cells

To determine whether the NTCons region is essential for LC3B–PE conjugation and autophagic flux in the presence of additional autophagy machinery in mammalian cells, we reintroduced wild-type hAtg3, hAtg3L23T, or hAtg3P21A variant into Atg3−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) by lentiviral transduction and examined LC3B lipidation and autophagic flux by monitoring the lysosomal turnover of LC3B-II in the presence or absence of the lysosomal inhibitor bafilomycin A1 (BafA1), as described previously23. While the lipidation of LC3B was absent in Atg3−/− MEFs, the expression of hAtg3 rescued not only LC3B–PE conjugation, but also starvation-induced autophagic flux (Fig. 4a–c). In contrast, the introduction of hAtg3L23T into Atg3−/− MEFs nearly completely failed to induce LC3B-II production and autophagic flux, whereas the introduction of hAtg3P21A partially rescued LC3B lipidation (Fig. 4a, b). The LC3B-II level of Atg3−/− cells expressing hAtgP21A was significantly lower compared to that of Atg3−/− cells expressing hAtg3. Although there was no statistical difference in the basal autophagic flux, nutrient starvation induced a significantly high level of LC3B-II lysosomal turnover in Atg3−/− MEFs expressing hAtg3 compared to the empty vector, hAtg3L23T or hAtg3P21A (Fig. 4c). Collectively, the data strongly support that the NTCons region of Atg3 is important for LC3B lipidation and autophagic flux in vivo.

Fig. 4. hAtg3P21A and hAtg3L23T are impaired in inducing LC3B lipidation and autophagic flux in vivo.

Atg3 knockout (Atg3−/−) mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) stably expressing mCherry, mCherry-hAtg3, mCherry-hAtg3P21A, or mCherry-hAtg3L23T were cultured in complete media (CM) and starvation media (SM) with or without bafilomycin A1 (BafA1) for 3 h and subjected to immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. a Representative immunoblot (n = 6 blots). b Quantitative analysis of the relative LC3B–II level (n = 6 blots). c Relative basal and starvation-induced autophagic flux (n = 6 blots). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA test followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Data are presented as mean ± SD. P values: ****P < 0.0001 (b), ***P = 0.0001 and 0.0003 (left to right in b), **P = 0.0037 and 0.0011 (left to right in b) and 0.0014 and 0.0021 (left to right in c), and *P = 0.0097 (c).

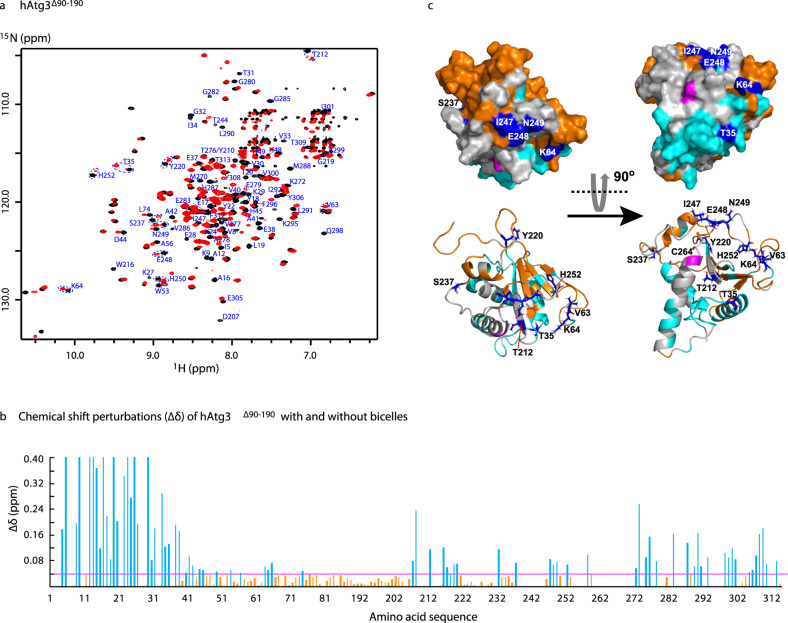

NMR chemical shift perturbations provide molecular insights into the functional role of hAtg3’s NT conserved region

Our in vitro biochemical and in vivo cellular experiments demonstrate that the hAtg3 NTCons region is required for LC3B–PE conjugation. To discern the molecular basis of this regulation, we performed solution NMR CSP experiments. hAtg3 is a dynamic protein and more than 1/3 of its 314 residues are expected to be in unstructured regions, based on existing Atg3 structures. To facilitate NMR studies, we first optimized hAtg3 constructs. Deletion of the unstructured region from residues 90 to 190 (hAtg3∆90-190) visibly improves NMR spectral quality (Supplementary Fig. 6). Moreover, hAtg3∆90-190 retains about 50% of its conjugase activity compared to the wild type (Supplementary Fig. 7). The reduced conjugation activity of hAtg3∆90-190 is at least partially due to a slow formation of the LC3B-hAtg3∆90-190 intermediate as a result of removing its major Atg7 interacting site (residues 157–181)11,24,25. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 8a, LC3B-hAtg3 intermediate formation for the wild-type hAtg3 is near complete (~70%) within 30 min and only about ~25% of the intermediate is formed for the hAtg3∆90-190 construct after 1 h, despite the fact that the stability of LC3B-hAtg3 and LC3B-hAtg3∆90-190 intermediates in aqueous solution is comparable (Supplementary Fig. 8b). Additionally, the LC3B–PE formation for the hAtg3∆90-190, but not hAtg3, can be improved by increasing the concentration of mAtg7 (mouse Atg7) in the reaction buffer (Supplementary Fig. 8c). When recapitulating the NT point mutations in this 90–190 deletion construct, the hAtg3∆90-190_P21A shows decreased activity when compared to wild-type protein and the hAtg3∆90-190_L23T has nearly abolished conjugation activity, consistent with the behavior of the full-length proteins (Supplementary Fig. 8d).

Using TROSY-based assignment experiments, we assigned about 95% of its backbone resonances (Supplementary Fig. 9). The majority of unassigned residues (residues 260–269) are near the active site C264 and their resonances are not observed, most likely as a result of intermediate exchange. This indicates that the active site region of hAtg3 is probably involved in millisecond motions in aqueous solution. Interestingly, similar dynamics have been observed for yAtg3 in a recent study26. In addition, we prepared an hAtg3 construct without the 25 N-terminal residues (hAtg3∆1-25, Supplementary Fig. 10) and assigned about 80% of its backbone and Cβ resonances despite the fact that this construct contains a long stretch of ~100 unstructured residues (to be published). Using assigned shifts of 13Cα, 13Cβ, 13C’, 15N, and 1HN, we generated structural models for hAtg3∆1-25 with the PONOMA program27. Out of 2000 calculated models, the ten lowest-energy predictions show good convergence with an RMSD of 1.7 Å for structured regions (Supplementary Fig. 11).

In order to identify a membrane model that is compatible with high-resolution NMR studies of hAtg3 and supports its conjugase activity, we tested whether several commonly used membrane mimics including micelles, nanodiscs, and bicelles could replace liposomes in the in vitro conjugation assay. Consistent with a previous report28, LC3B–PE conjugation does not occur in LPC/LPG/LPE micelles (Supplementary Fig. 12a). In addition, no LC3B–PE conjugation is detected in POPC/POPG/POPE nanodiscs (Supplementary Fig. 12b). This is most likely due to the lack of strong interactions between hAtg3 NTs and the surface of the relatively tightly packed lipid bilayers. Consistent with this, only small CSPs and intensity perturbations (characteristics of transient interactions) are observed in the TROSY spectra of hAtg3∆90-190 with and without nanodiscs (Supplementary Fig. 13). By comparison, the LC3B–PE conjugation reaction in DMPC/DMPG/LPE/DHPC bicelles proceeds at a rate comparable to that in liposomes (Supplementary Fig. 12c). The dynamic planar surfaces of bicelles are loosely packed and presumably mimic a membrane with the type of packing defects that are required for interactions with hAtg3. The observation that hAtg3 is more active in larger bicelles (Supplementary Fig. 12c), where the planar faces have a proportionally larger fraction of the bicelle’s surface, further supports the notion that the protein mainly interacts with the planar faces instead of the highly curved edges of bicelles. We also examined the LC3B–PE conjugation reaction in bicelles for the NT point mutants. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 12c, the hAtg3P21A and hAtg3V8D_V15K constructs shows much reduced or no activity, consistent with the results from in vivo cellular assay and in vitro conjugation assay using liposomes. However, in bicelles the hAtg3L23T construct functions differently. In contrast to its almost total inactivity in the in vitro conjugation assay when using liposomes and the in vivo cellular assay, the hAtg3L23T construct shows moderate conjugation activity using bicelles. As a result of these observations, we have focused the NMR structural analysis in bicelles on the hAtg3∆90-190 and hAtg3∆90-190_P21A constructs.

Figure 5a shows an overlay of the TROSY spectra of hAtg3∆90-190 in the absence (black) and presence (red) of bicelles, in which pronounced spectral changes are observed. Despite the large size of bicelles and exchange broadening, we have been able to assign about 80% of the hAtg3 residues in the bicelle-bound state. Perturbed resonances (some of which are labeled with assignments in the spectra) are distributed throughout the NT of hAtg3 and the C-terminal part of the protein, as shown in Fig. 5b. The large shifts for hAtg3 NT residues are expected since they undergo transition from a random coil to an α-helix structure as demonstrated by secondary 13Cα chemical shifts for residues 3–19 in aqueous solution and in bicelles (Supplementary Fig. 14). On the other hand, large CSPs for resonances from the C-terminal part of the protein (such as Y220, S237, E248, and H252 in Fig. 5a) suggest that structural rearrangements beyond hAtg3’s NT occur upon interaction with the bilayer. In Fig. 5c, the perturbed (cyan) and unperturbed (orange) residues are highlighted on an hAtg3 structural model; unassigned residues are colored white. Interestingly, perturbed and unassigned residues congregate on one side around the active site (C264) while the unperturbed residues cluster on the opposite side.

Fig. 5. Binding of hAtg3∆90-190 to bicelles results in structural arrangements beyond its NT.

a Overlay of 2H,15N,13C-labeled hAtg3∆90-190 TROSY spectra acquired on a Bruker 600 MHz spectrometer at 25 °C, pH 7.5 in the absence (black) and presence (red) of bicelles (DMPC:DMPG:DHPC = 4:1:20, molar ratio). b Plots of hAtg3∆90-190 15N and 1H chemical shift perturbations (CSPs, ∆δ) upon interaction with bicelles against residue numbers. , and represent the changes in 1H and 15N chemical shifts upon interacting with bicelles, respectively. c Surface and ribbon representations of a hAtg3 structural model with perturbed residues (∆δ ≥0.04 ppm) colored cyan and unperturbed residues (∆δ < 0.04 ppm) colored orange. The active site C264 is highlighted in magenta and unassigned residues are colored white. Some resonances displaying large CSPs are circled in (a) and their corresponding residues are colored blue in (c).

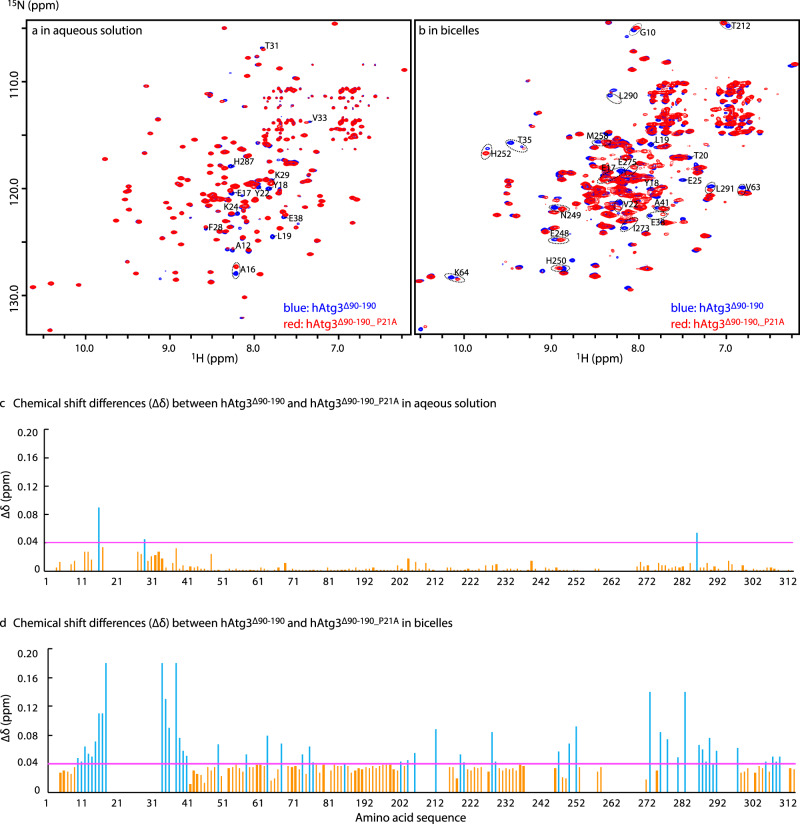

To understand why the hAtg3P21A mutant fails to catalyze the transfer of LC3B from LC3B-hAtg3 to PE in the membrane despite having wild-type-like membrane binding and thioester intermediate formation, we examined its behavior in the membrane-bound state. Figure 6a, b displays overlays of TROSY spectra of hAtg3∆90-190 and hAtg3∆90-190_P21A in aqueous solution and in bicelles. In the absence of bicelles, the two spectra overlap well and all shifted resonances occur near the mutation site except H287, which is located at the beginning of the last α-helix (Fig. 6a, c). This indicates only local structural changes. Conversely, in bicelles there are extensive perturbations in both the NT and C-terminal portions of hAtg3∆90-190_P21A compared to the wild type (Fig. 6b, d), illustrating that while hAtg3∆90-190_P21A also undergoes a conformational shift upon membrane binding, the structure of membrane-bound hAtg3∆90-190_P21A differs from the structure of membrane-bound hAtg3∆90-190. This suggests that the loss of conjugase activity of hAtg3P21A may be due to its altered membrane-bound structure. Additionally, as expected, hAtg3∆90-190_V8D_V15K, a mutant that is unable to bind the membrane and has no LC3B–PE conjugation activity (Fig. 3), shows minimal conformational shifts in bicelles (Supplementary Fig. 15). Thus, together, our NMR data show that the binding of the hAtg3 N-terminal AH to the membrane results in structural rearrangements in the C-terminal part of the protein around its active site and furthermore, the NTCons region of hAtg3 is a key mediator of this structural transition.

Fig. 6. Binding of hAtg3∆90-190_P21A to bicelles induces structural changes different from the wild-type protein.

a, b Overlay of TROSY spectra of 2H,15N,13C-labeled hAtg3∆90-190 (blue) and hAtg3∆90-190_P21A (red) in aqueous solution (pH 7.5) and in bicelles (DMPC:DMPG:DHPC = 4:1:20, molar ratio, pH 7.5), respectively. Both spectra were acquired on a Bruker 600 MHz spectrometer at 25 °C. c and d Plots of chemical shift differences (∆δ) between hAtg3∆90-190 and hAtg3∆90-190_P21A against residue numbers in aqueous solution and in bicelles, respectively.

Discussion

This study reveals an expanded role for the hAtg3 NT in the regulation of LC3B–PE conjugation. In isolation, human and yeast NTs have similar membrane-geometry sensitivity, but they are not functionally exchangeable; swapping their NTs (hAtg3yNT) results in a nearly complete loss of its catalytic activity. This is due to the NTCons region, rather than the membrane-interacting region where there is sequence divergence between homologs. Indeed, we found that mutations of the conserved Pro21, or other residues in its vicinity, had deleterious effects on LC3B–PE conjugation despite the fact that proteins harboring these mutations bind to the membrane and form LC3B-hAtg3 intermediates normally. This indicates that while the N-terminal AH is necessary for targeting hAtg3 to the membrane, it is not sufficient for LC3B–PE conjugation. For LC3B–PE conjugation to occur, the hAtg3 NTCons region must convey its membrane geometry-dependent interactions to its active site, as evidenced by NMR CSP data. The essential function of the hAtg3 NTCons region is also demonstrated in vivo by the hAtg3P21A and hAtg3L23T mutants with a caveat that decreased Atg12–Atg5 conjugation has been reported previously in Atg3 knockout cells29.

Direct structural information for the LC3-Atg3 intermediate, its membrane-bound activated form, and the mechanism of activation remains elusive. The current model for Atg3 activation is based on an analysis of the yAtg3 structure crystallized at pH 5.8 (assumed to be an inactive state)11, the AtAtg3 (A. thaliana Atg3) structure crystallized at pH 8.0 (assumed to be an active state)9, and Cys cross-linking data by the Ohsumi group13. In this model, interactions between yAtg3 and Atg5-Atg12/Atg16 induce a structural rearrangement of the active site of yAtg3, which presumably involves the catalytic Cys234 orienting toward a Thr213, similar to the configuration seen in the active site of an E2 ligase30–32. Furthermore, a recent study showed that yAtg3 is autoinhibited, and identified an allosteric switch (residues 129–142) that may mediate a conformational rearrangement in its active site upon interacting with the Atg5–Atg12/Atg16 complex26. Our studies indicate that an additional structural arrangement occurs in and around the active site of hAtg3 due to its N-terminal AH binding to the membrane. This structural change, which is presumably distinct from that induced by Atg5–Atg12/Atg16 binding, is functionally critical for transferring LC3B from LC3B-hAtg3 to PE in the membrane. Mutants such as hAtg3P21A, which show altered structural rearrangements after membrane binding catalyze little LC3B–PE conjugation. We speculate that upon the binding of hAtg3’s AH to the membrane, the NTCons region triggers a conformational change that brings the thioester LC3B-hAtg3 intermediate to the membrane surface in close proximity to substrate PE lipids and orients it optimally for the transfer of LC3B to PE. Although this study has been focused on LC3B, the membrane-induced structural arrangements may also be required for the lipidation of other members of the Atg8 family since the same chemistry is used to catalyze their conjugations to PE lipids. On the other hand, recent studies have revealed that each of the LC3/GABARAP superfamily members may have a distinct role in the process of autophagy33,34. It is conceivable that the N-terminal region of Atg3 might influence the lipidation reaction among the family members differently, and this remains to be examined.

Membrane interactions that lead to changes in protein structure and activity have been reported in other systems, such as Arf1 and ArfGAP1. In Arf1, the binding of its N-terminal AH to the positively curved membrane results in a conformational change in its active site for GTP loading35. For ArfGAP1, the activation of the protein depends on the insertion of its ALPS motif into the highly curved membrane36 although the structural and molecular mechanism of this activation is not yet known. To understand how the interaction of hAtg3 with the membrane contributes to its activity, high-resolution structural information on its membrane-bound active states is necessary. We are working toward this goal despite the challenges inherent in obtaining this data. Atg3 has been referred to as an intrinsically disordered protein37 and its catalytic site in the apo-state is in a constant state of conformational exchange as described above. In the TROSY spectrum of hAtg3 bound to bilayer-like bicelles, many resonances around the active site suffer from exchange broadening which complicates their backbone resonance assignment and detailed NMR structural analysis.

In summary, we have demonstrated that in hAtg3, the membrane geometry-sensitive AH and conserved region of the NT work together to promote LC3B–PE conjugation only on the target membrane. While future studies are required to fully understand the mechanism of action, our results support an emerging concept that membrane geometry provides an essential cue for spatial regulation of autophagosome biogenesis during autophagy38–41.

Methods

Atg3 peptides

Atg3 human (MQNVINTVKGKALEVAEYLTPVLKESK) and yeast (MIRSTLSSWREYLTPITHKST) NTs and hAtg3 NT mutants (A12W, A12W_P21A, A12W_L23T, A12W_V8D_V15K) were synthesized by GenScript (Piscataway, New Jersey) at >95% purity as determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and mass spectroscopy (MS). Peptides were lyophilized in order to further remove trace organic solvents. Peptide stock solutions were prepared at a concentration of 1 mg/mL by weighing lyophilized peptide and the concentrations were determined by a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). The yAtg3 NT peptide was prepared by dissolving the peptide in H2O. The hAtg3 NT peptides were prepared by dissolving the peptide in 0.1% HCl in water. Peptides were stored at −20 °C before use.

Preparation of liposomes, bicelles, and nanodiscs

All lipids were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc., including POPC (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl- sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine), DOPG (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho1’-rac-glycerol), DOPE (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanol-amine), DMPC (1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine), DMPG (1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1’-rac-glycerol) (sodium salt)), DHPC (1,2-dihexanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine), LPC (1-myristoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine), LPG (1-myristoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1’-rac-glycerol) (sodium salt)), and LPE (1-myristoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine).

For liposome preparation, lipids in chloroform were added to a glass tube and dried to a thin film by spinning with heat for an hour using a condenser rotor SpeedVac, followed by lyophilization overnight once the volatile organics were removed. Lipids were rehydrated with H2O for 1 h at 42 °C and vortexed every 15 min. Rehydrated lipids were transferred to a 1.5 mL plastic tube and put through 5 cycles of freeze-thaw using a dry ice bath and a room temperature water bath. The mixture was then transferred to a clean glass tube for bath sonication (BRANSON 3510R-MT Bransonic Ultrasonic Cleaner). The lipids were sonicated for 15-min intervals until clear, then stored at room temp. If liposomes were not consumed within 2 days, they were sonicated for an additional 5–10 min before use. Extruded liposomes were prepared as described previously42. Briefly, lipids were prepared as above, but instead of sonication, the rehydrated lipids were passed through a 0.05 μm filter 11 times (SPARTAN HPLC Syringe Filter) in a liposome extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids) after the dry ice bath. The extruded liposomes were collected and stored at room temperature.

Bicelles and nanodiscs (cNW9, circulated nanodisc width of 9 nm) were prepared as described previously43–45. Briefly, for the preparation of bicelles, DMPC, DMPG, and LPE were mixed together with double distilled H2O (ddH2O), frozen on ethanol/dry ice, and thawed at 42 °C for 3 freeze-thaw cycles. DHPC in ddH2O was then added into the mixture and quickly vortexed to form a clear solution. The solution was frozen on ethanol/dry ice and slowly thawed at room temperature for use. For the preparation of nanodiscs, purified NW9 was circularized to form cNW9 (circularized NW9) using freshly made sortase in buffer (300 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2). cNW9 was purified through Ni column and then S200 16/60 column. The purified cNW9 was exchanged into a buffer of 20 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, pH 8.0, and 20 mM sodium cholate, and incubated with lipids (POPC/POPE/POPG in a molar ratio of 2/2/1, cNW9/lipid in a molar ratio of 1/60) on ice for 1 h. Sodium cholate was then removed by incubation with Bio-beads SM-2 (Bio-Rad) for 1 h on ice followed by incubation overnight at 4 °C. Bio-beads were removed through 0.22 μm nitrocellulose filter. The nanodisc preparations were further purified by size-exclusion chromatography and assessed using SDS–PAGE.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy

CD spectroscopy was performed on Jasco 710 and 1500 J-spectropolarimeters. Samples contained 0.1 mg/mL of hAtg3 or yAtg3 NT peptides in a buffer of 20 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.5, and 50 mM NaCl with and without liposomes in a 0.1 mm path length cuvette. CD spectra were collected for 200–250 nm at 25 °C. Each spectrum was collected by averaging three scans at a rate of 50 nm/min and 1 nm or 0.2 nm step size. After recording, the spectra were subjected to background subtractions and baseline corrections.

Protein expression and purification

Human Atg3 (hAtg3) and LC3B (with Gly120 as the last amino acid) were subcloned into the pET28a expression vector at the BamHI/XhoI site with His-tag and T7-tag and a thrombin cleavage site at the N-termini, and plasmids were transformed into chemically competent Rosetta™(DE3) pLysS cells for expression. All hAtg3 mutants were generated using the Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (New England Biolabs) or the QuickChange MultiSite-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (New England Biolabs) with corresponding primers listed in Supplementary Table 1 and verified by sequencing. Typically, a single colony was selected to grow in small volume of LB medium overnight at 37 °C as a starter culture and then inoculated into a large volume of LB medium (for unlabeled proteins) or M9 medium supplemented with D-glucose (or 3 g/L D-glucose-13C6 and D2O) and 15NH4Cl (1 g/L) for 15N (or 15N/13C/2H) labeled samples at 37 °C until OD600 reached 0.8. The temperature was then lowered to 25 °C and cells were induced with 0.5 mM IPTG for ~16 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and the pellets were stored at −80 °C until use. Mouse Atg7 (mAtg7) was subcloned into the pFast-BacI baculovirus vector at the StuI/XbaI sites with a His-tag at the N terminus and expressed in High Five insect cells46.

Cell pellets (for hAtg3, LC3B, or mAtg7) were homogenized with a lysis buffer of 20 mM phosphate, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM beta mercaptoethanol (BME), and 1 mM MgCl2 supplemented with benzonase nuclease and complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), and were lysed using sonication on ice with 2 s on/7 s off intervals for 18 min total duration. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (Sorvall RC5B Plus Refrigerated Centrifuge) at 26,900g at 10 °C for 30 min. Supernatants were collected, and either incubated with HisPur Ni-NTA resin and applied to a gravity column or loaded onto a Ni-NTA column (HisTrap HP). The column was washed with PBS buffers (20 mM phosphate, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM BME) without and with 30 mM imidazole, and then eluted with PBS buffer containing 500 mM imidazole. For biochemical assays, the elute of hAtg3 was concentrated and exchanged to a low-salt buffer of 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, and 2 mM BME, and then loaded onto a 1 mL Capto Q ion exchange column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The column was washed with a buffer of 50 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 2 mM BME, and targeted protein was eluted with a rising gradient of 50 mM HEPES, 1 M NaCl, and 2 mM BME until no more protein was indicated by the UV measurements. Relevant fractions with purities no less than 90% were pooled after analysis on an SDS-PAGE gel. For NMR experiments, the elute of hAtg3 from Ni-column was concentrated and exchanged to a buffer (10 mL) containing 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 2 mM BME, and followed by the addition of 0.1% (v/v) TWEEN20 and 50 units thrombin to remove T7-tag and His-tag for an overnight agitation at 4 °C. The solution was then subjected to a Q-column and further purified by size-exclusion chromatography using an S75 column (HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75) and a buffer of 50 mM HEPES, 1 M NaCl, and 1 mM DTT. For LC3B and Atg7, elutes from the Ni-column were concentrated and subjected to S75 column purification. Purified hAtg3 or mutant proteins, LC3B and mAtg7 were exchanged into a buffer of 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 2 mM TCEP (tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine). Protein concentration was assayed using a Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA).

In vitro conjugation assay

The in vitro conjugation was conducted similarly to previous descriptions15. Typically, 2.5–5.0 μM hAtg3 or mutant (with a His tag and T7 tag at the N-termini47) was combined with 5 μM LC3B, 0.5–1 μM mAtg7, and 1 mM MgCl2 in a reaction buffer (50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM TCEP, and pH 7.5) of 37.5 μL. First, 3.7 μL were removed for a control, then 1 mM ATP was added and the reaction was allowed to proceed for 30 min at 37 °C for intermediate formation. Then, 3.75 μL were removed to check for intermediates, and an additional 3.75 μL were removed as a non-liposome containing control. Then, 1 mM liposomes were added to the reaction system (final volume of 35 μL). The reaction was allowed to proceed at 37 °C with gentle agitation, with 4.5 μL samples removed at 0, 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, and 180 min. Samples were mixed with 4 μL 4X protein loading buffer (10% w/v SDS, 10% BME, 40% Glycerol, 250 mM Tris-HCL, pH 6.8, and 0.4% bromophenol blue dye), frozen immediately to stop the reaction, and stored at −80 °C until analyzing with 18% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. For gel electrophoresis, samples were heated at 95 °C for 3 mins. Gels were stained with SimplyBlue SafeStain (Invitrogen) until bands became discernable. Gels were destained in deionized water overnight, imaged on a BioRad Chemidock MP imager, and analyzed using ImageJ.

Liposome co-sedimentation assay

First, 2 μM hAtg3 (or its mutants) was mixed with 800 μM sonicated liposomes (POPC/DOPG/DOPE with a molar ratio of 3:2:5) or without liposomes as a control in a buffer A of 50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, and 2 mM TCEP. Then, the mixture of a total volume 300 μL was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, and 12 μL were removed and mixed with 4 μL 4X protein loading buffer (total, T). The remaining mixture was subjected to ultracentrifugation at 160,000g for 2 h at 4 °C (Optima MAX Ultracentrifuge). After removing the supernatant, the pellets were gently washed once with 288 μL buffer A and resuspended in 288 μL buffer A. Then, 12 μL of the supernatant (S) and the pellet resuspension (P) were mixed with 4 μL 4X protein loading buffer, respectively, for gel electrophoresis (NuPAGE 10% Bis-Tris). Samples were heated at 95 °C for 3 mins for gel electrophoresis.

Mammalian cell culture

HEK293T cells (ATCC; CRL-3216) and Atg3−/− MEFs provided by Dr. Shengkan (Victor) Jin (Rutgers University - Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, NJ) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modification of Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1x Antibiotic Antimycotic Solution (AA) (Corning, 30-004-CI).

Plasmid construction

hAtg3, hAtg3P21A, and hAtg3L23T cDNAs were amplified by PCR (forward: 5′-GAGCTGTACAAGTCTAGAGTGATGCAGAATGTGATTAATA-3′; reverse 5′-CGCAGATCCTTGCGGCCGCGTTACATTGTGAAGTGTCTTG-3′). Purified PCR products were subcloned into pCDH1-CMV-mCherry-MCS-EF1-puro viral backbone using NheI and BamHI.

Lentiviral packaging, transduction, and cell sorting

HEK293T cells were transfected with Invitrogen ViraPower lentiviral packaging plasmids (pLP1, pLP2, and pLP/VSVG) and viral vector using Lipofectamine 3000 per the manufacturer’s protocol. Culture medium was replaced 6 h after transfection; viral supernatant was collected 24 and 52 h post-transfection and subjected to 0.45 μm filtration. Atg3−/− MEFs were incubated with filtered viral supernatant for 24 h and subjected to puromycin selection 48 h post-transduction for 3 days. The transduction was repeated three times, followed by flow cytometry sorting based on mCherry intensity. The cells were divided into three intensity levels of low, medium, and high. MEF cells expressing medium mCherry intensity were used for autophagic flux assay.

Autophagic flux assay

Cells were incubated in complete media or starvation media (amino-acid and serum free) in the presence or absence of 100 nM bafilomycin A1 (BafA1) for 3 h and subjected to immunoblotting using the mCherry antibody (Abcam, ab125096) with a ratio of 1:1000, the β-actin antibody (Sigma, A5441-100UL) with a ratio of 1:10,000, and the LC3 antibody (Novus Biologicals, NB100-2220) with a ratio of 1:5,000. To quantify the LC3-II level, the experiments were repeated six times. The signal intensity of LC3-II was measured using Image Studio version 5 software (LI-COR Biotechnology), then normalized to the intensity of β-actin of the same sample. To calculate the relative LC3-II level, the LC3-II value of Atg3−/− MEFs expressing mCherry-hAtg3 in starvation medium with BafA1 was set to be 1. The autophagic flux was calculated by subtracting the LC3-II value in the absence of BafA1 from that in the presence of BafA1 in complete (basal) or starvation (induced) medium. All the values were then normalized with the value of Atg3−/− MEFs expressing mCherry-hAtg3 being set as 1. The data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA test followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test using GraphPad Prism7.0.

NMR spectroscopy

Typical NMR samples contained 0.3–0.5 mM labeled protein in a buffer of 25–50 mM HEPES, pH 6.5 (or 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM TCEP, and 0.02% NaN3. For samples with 12% bicelles, the pH was at 7.5 since the protein precipitates after a few days at pH 6.5. All NMR data were acquired at 25 °C on Bruker 600 or 850 MHz spectrometers equipped with cryoprobes. The data were processed using NMRPipe and analyzed using NMRView. Backbone and 13Cβ resonance assignments were carried out using TROSY-based triple resonance HNCO, HN(CA)CO, HNCA, HN(CO)CA, HNCACB, and HN(CO)CACB experiments. Typical data acquisition parameters are listed in Supplementary Table 2. The CSPs of 1H and 15N backbone resonances were calculated as , and represent the changes in 1H and 15N chemical shifts48.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the lab of Dr. Sascha Martens for providing the yeast expression vector for Atg3, Atg7, and Atg8. We thank Dr. Christie McCracken for helping with mouse Atg7 preparation, Dr. Maria Bewley and Dr. Charles R. Sanders for helping with nanodisc and bicelle preparations, Dr. Thomas Spratt for discussions, and Dr. Ad Bax for his support with POMONA modeling. We are thankful for financial support from the National Institutes of Health NIGMS (5R01GM105963, 1R01GM127730, 1R01GM127954, R01 CA166413, and R01 GM113013) and the Four Diamonds Fund.

Source data

Author contributions

Y.S.Y., E.R.T, V.B., and Z.Y.T. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and drafted figures and the paper. Y.S. helped with PONOMA structural modeling of hAtg3. X.J.J. provided essential reagents and experimental procedures. J.M.F. helped with Atg7 purification and manuscript preparation. F.T. and H.G.W. conceived, planned, and supervised this study, analyzed the data, and wrote the final paper with feedback from all authors.

Data availability

NMR resonance assignments have been deposited with the BMRB (www.bmrb.io) with accession numbers 50479 (hAtg3∆90-190 in aqueous solution), 50480 (hAtg3∆90-190 in bicelles), 50481 (hAtg3∆90-190_P21A in bicelles), and 50470 (hAtg3∆1-25 in aqueous solution). PDBs of 3VX8 [10.2210/pdb3VX8/pdb], 6OJJ [10.2210/pdb6OJJ/pdb], and 2DYT [10.2210/pdb2DYT/pdb] are available at www.rcsb.org. All other data and materials that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Vladimir Rogov and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yansheng Ye, Erin R. Tyndall, Van Bui.

Contributor Information

Hong-Gang Wang, Email: huw11@psu.edu.

Fang Tian, Email: ftian@psu.edu.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-20607-0.

References

- 1.Lamb CA, Yoshimori T, Tooze SA. The autophagosome: origins unknown, biogenesis complex. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013;14:759–774. doi: 10.1038/nrm3696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurley JH, Schulman BA. Atomistic autophagy: the structures of cellular self-digestion. Cell. 2014;157:300–311. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. An overview of the molecular mechanism of autophagy. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2009;335:1–32. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-00302-8_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y. The role of Atg proteins in autophagosome formation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2011;27:107–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abada A, Elazar Z. Getting ready for building: signaling and autophagosome biogenesis. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:839–852. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johansen T, Lamark T. Selective autophagy goes exclusive. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:395–397. doi: 10.1038/ncb2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaufmann A, Beier V, Franquelim HG, Wollert T. Molecular mechanism of autophagic membrane-scaffold assembly and disassembly. Cell. 2014;156:469–481. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sawa-Makarska J, et al. Cargo binding to Atg19 unmasks additional Atg8 binding sites to mediate membrane-cargo apposition during selective autophagy. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:425–U100. doi: 10.1038/ncb2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamaguchi M, et al. Noncanonical recognition and UBL loading of distinct E2s by autophagy-essential Atg7. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012;19:1250–1256. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suzuki H, Osawa T, Fujioka Y, Noda NN. Structural biology of the core autophagy machinery. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2017;43:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamada Y, et al. The crystal structure of Atg3, an autophagy-related ubiquitin carrier protein (E2) enzyme that mediates Atg8 lipidation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:8036–8043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611473200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanada T, et al. The Atg12-Atg5 conjugate has a novel E3-like activity for protein lipidation in autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:37298–37302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C700195200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakoh-Nakatogawa M, et al. Atg12-Atg5 conjugate enhances E2 activity of Atg3 by rearranging its catalytic site. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013;20:433–439. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanada T, Satomi Y, Takao T, Ohsumi Y. The amino-terminal region of Atg3 is essential for association with phosphatidylethanolamine in Atg8 lipidation. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:1078–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nath S, et al. Lipidation of the LC3/GABARAP family of autophagy proteins relies on a membrane-curvature-sensing domain in Atg3. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:821–821. doi: 10.1038/ncb3017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hervas JH, et al. Human ATG3 binding to lipid bilayers: role of lipid geometry, and electric charge. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:15614. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15057-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dancourt J, Melia TJ. Lipidation of the autophagy proteins LC3 and GABARAP is a membrane-curvature dependent process. Autophagy. 2014;10:1470–1471. doi: 10.4161/auto.29468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bigay J, Casella JF, Drin G, Mesmin B, Antonny B. ArfGAP1 responds to membrane curvature through the folding of a lipid packing sensor motif. EMBO J. 2005;24:2244–2253. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun AR, Lacy MM, Ducas VC, Rhoades E, Sachs JN. α-Synuclein-induced membrane remodeling is driven by binding affinity, partition depth, and interleaflet order asymmetry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:9962–9972. doi: 10.1021/ja5016958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gill RL, et al. Structural basis for the geometry-driven localization of a small protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:E1908–E1915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423868112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oh-oka K, Nakatogawa H, Ohsumi Y. Physiological pH and acidic phospholipids contribute to substrate specificity in lipidation of Atg8. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:21847–21852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801836200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larsson E, Hubert M, Lundmark R. Analysis of protein and lipid interactions using liposome co-sedimentation assays. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020;2169:119–127. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-0732-9_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serfass JM, et al. Endophilin B2 facilitates endosome maturation in response to growth factor stimulation, autophagy induction, and influenza A virus infection. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:10097–10111. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.792747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohashi K, Otomo T. Identification and characterization of the linear region of ATG3 that interacts with ATG7 in higher eukaryotes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015;463:447–452. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.05.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Metlagel Z, Otomo C, Takaesu G, Otomo T. Structural basis of ATG3 recognition by the autophagic ubiquitin-like protein ATG12. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:18844–18849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314755110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng YM, et al. A switch element in the autophagy E2 Atg3 mediates allosteric regulation across the lipidation cascade. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:3600. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11435-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen Y, Bax A. Homology modeling of larger proteins guided by chemical shifts. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:747–750. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ichimura Y, et al. In vivo and in vitro reconstitution of Atg8 conjugation essential for autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:40584–40592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405860200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sou Y, et al. The Atg8 conjugation system is indispensable for proper development of autophagic isolation membranes in mice. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:4762–4775. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e08-03-0309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plechanovova A, Jaffray EG, Tatham MH, Naismith JH, Hay RT. Structure of a RING E3 ligase and ubiquitin-loaded E2 primed for catalysis. Nature. 2012;489:115–120. doi: 10.1038/nature11376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dou H, Buetow L, Sibbet GJ, Cameron K, Huang DT. BIRC7-E2 ubiquitin conjugate structure reveals the mechanism of ubiquitin transfer by a RING dimer. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012;19:876–883. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Streich FC, Lima CD. Structural and functional insights to ubiquitin-like protein conjugation. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2014;43:357–379. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-051013-022958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grunwald DS, Otto NM, Park JM, Song D, Kim DH. GABARAPs and LC3s have opposite roles in regulating ULK1 for autophagy induction. Autophagy. 2020;16:600–614. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2019.1632620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen TN, et al. Atg8 family LC3/GABARAP proteins are crucial for autophagosome-lysosome fusion but not autophagosome formation during PINK1/Parkin mitophagy and starvation. J. Cell. Biol. 2016;215:857–874. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201607039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lundmark R, Doherty GJ, Vallis Y, Peter BJ, McMahon HT. Arf family GTP loading is activated by, and generates, positive membrane curvature. Biochem. J. 2008;414:189–194. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bigay J, Gounon P, Robineau S, Antonny B. Lipid packing sensed by ArfGAP1 couples COPI coat disassembly to membrane bilayer curvature. Nature. 2003;426:563–566. doi: 10.1038/nature02108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Popelka H, Uversky VN, Klionsky DJ. Identification of Atg3 as an intrinsically disordered polypeptide yields insights into the molecular dynamics of autophagy-related proteins in yeast. Autophagy. 2014;10:1093–1104. doi: 10.4161/auto.28616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nguyen N, Shteyn V, Melia TJ. Sensing membrane curvature in macroautophagy. J. Mol. Biol. 2017;429:457–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fan W, Nassiri A, Zhong Q. Autophagosome targeting and membrane curvature sensing by Barkor/Atg14(L). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:7769–7774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016472108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lystad AH, et al. Distinct functions of ATG16L1 isoforms in membrane binding and LC3B lipidation in autophagy-related processes. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019;21:372–383. doi: 10.1038/s41556-019-0274-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carlsson SR, Simonsen A. Membrane dynamics in autophagosome biogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 2015;128:193–205. doi: 10.1242/jcs.141036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gill RL, Wang XS, Tian F. A membrane proximal helix in the cytosolic domain of the human APP interacting protein LR11/SorLA deforms liposomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1848:323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nasr ML, et al. Covalently circularized nanodiscs for studying membrane proteins and viral entry. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:49–52. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu ZM, Hong HF, Zhao XR, Wang X. Efficient expression of sortase A from Staphylococcus aureus in Escherichia coli and its enzymatic characterizations. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2017;4:13. doi: 10.1186/s40643-017-0143-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Losonczi JA, Prestegard JH. Improved dilute bicelle solutions for high-resolution NMR of biological macromolecules. J. Biomol. NMR. 1998;12:447–451. doi: 10.1023/A:1008302110884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sung LY, et al. Efficient gene delivery into cell lines and stem cells using baculovirus. Nat. Protoc. 2014;9:1882–1899. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shao YF, Gao ZH, Feldman T, Jiang XJ. Stimulation of ATG12-ATG5 conjugation by ribonucleic acid. Autophagy. 2007;3:10–16. doi: 10.4161/auto.3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grzesiek S, et al. The solution structure of HIV-1 Nef reveals an unexpected fold and permits delineation of the binding surface for the SH3 domain of Hck tyrosine protein kinase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1996;3:340–345. doi: 10.1038/nsb0496-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

NMR resonance assignments have been deposited with the BMRB (www.bmrb.io) with accession numbers 50479 (hAtg3∆90-190 in aqueous solution), 50480 (hAtg3∆90-190 in bicelles), 50481 (hAtg3∆90-190_P21A in bicelles), and 50470 (hAtg3∆1-25 in aqueous solution). PDBs of 3VX8 [10.2210/pdb3VX8/pdb], 6OJJ [10.2210/pdb6OJJ/pdb], and 2DYT [10.2210/pdb2DYT/pdb] are available at www.rcsb.org. All other data and materials that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.