Abstract

Silicosis is a major health issue among workers exposed to crystalline silica. Genetic susceptibility has been implicated in silicosis. The present research demonstrates key regulatory targets and propagated network of gene/miRNA/transcription factor (TF) with interactions responsible for silicosis by integrating publicly available microarray data using a systems biology approach. Array quality is assessed with the Quality Metrics package of Bioconductor, limma package, and the network is constructed using Cytoscape. We observed and enlist 235 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) having up-regulation expression (85 nos) and down-regulation expression (150 nos.) in silicosis; and 24 TFs for the regulation of these DEGs entangled with thousands of miRNAs. Functional enrichment analysis of the DEGs enlighten that, the maximum number of DEGs are responsible for biological process viz, Rab proteins signal transduction (11 nos.) and Cellular Senescence (20 nos.), whereas IL-17 signaling pathway (16 nos.) and Signalling by Nuclear Receptors (14 nos.) etc. are Biological Pathway involving more DEGs. From the identified 1100 high target microRNA (miRNA)s involved in silicosis, 1055 miRNAs are found to relate with down-regulated genes and 847 miRNAs with up-regulated genes. The CDK19 gene (Up-regulated) is associated with 617 miRNAs whereas down-regulated gene ARID5B is regulated by as high as 747 high target miRNAs. In Prediction of Small-molecule signatures, maximum scoring small-molecule combinations for the DEGs have shown that CGP-60774 (with 20 combinations), alvocidib (with 15 combinations) and with AZD-7762 (24 combinations) with few other drugs having the high probability of success.

Subject terms: Functional clustering, Gene ontology, Gene regulatory networks, Microarrays, Computational biology and bioinformatics, Systems biology, Diseases

Introduction

The health risks of silica (silicon dioxide, SiO2) primarily responsible for silicosis, one of the most frequent pneumoconiosis are highly documented as an occupational disease in mining workers and others with silica exposures1–5. Silicosis is characterized by injury to the alveolar cells preceded by an initial immune response and followed by expansion and activation of fibroblasts, and finally the deposition of the extracellular matrix (ECM). Exposure dose, both duration and concentration plays an important role in the development of silicosis types6,7. Exposure to crystalline silica (particles < 10 μm in diameter), amorphous silica (non-crystalline) and nano-silica (particles < 100 nm in diameter) exhibit a different effect on the development of silicosis, pulmonary fibrosis, and inflammation and cytotoxicity, respectively8. Silicosis is broadly categorized into three forms namely, Chronic silicosis, (develops due to exposure at low-moderate exposure for 10 or more years), Accelerated silicosis (develops from moderate to high-level exposure within 10 years) and Acute silicosis (results from intense exposure for a few weeks or to 5 years from the time of initial exposure).

Silicosis is illustrious irreversible lung fibrosis simultaneously coupled with many other diseases, such as pulmonary tuberculosis , lung cancer, renal failure, systemic sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemiclupus erythematosus, gastrointestinal problem, and autoimmune conditions, etc.8,9. Silica-induced lung damage occurs by several mechanisms including cell death by apoptosis, fibrosis and production of cytokines10. Due to the graveness of the element, International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) enlisted crystalline silica as a carcinogen11. There is possibility of no apparent symptoms at the initial stage, however, silicosis can continue even after cease of the silica exposure making the situation critical, non-curable, irreversible and uncontrolled immune processes12. Scientist and Medicine personnel recommend identification of workers at risk, prevention of further exposure to silica dust by job rotation and use of personal protective equipment, etc. to control the issue enhanced with early diagnosisand prediction9,13. Bandyopadhyay et al.14 stated that diagnostic challenges arise as silicosis shows resemblance in radiological and clinical overlap with pulmonary tuberculosis and neoplastic lesions.Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the complex molecular mechanisms that underlie the disease. Identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in response to silica exposure and detail examination of the DEGs using the suitable statistical and computational approach may provide valuable information about the molecular mechanism(s) underlying the toxicity of crystalline silica15. The DEGs (upregulation/ downregulation) and/or their products, regulators, mostly transcription factors (TFs) and micro RNA (miRNA) following appropriate validation to recognize as a suitable biomarker(s) for silicosis is under investigation. A thorough investigation of possible molecular targets and mechanisms can make a way to achieve successful treatment options as well as prevention of potential adverse effects of silica exposure. The behavior of genes and genetic components due to silica exposure and toxicity are still rarely explained and are a vast area of scientific research16. Zhang et al.17. attempted to identify genome-wide aberrant DNA methylation profiling in lung tissues from silicosis patients using Illumina Human Methylation 450 K bead chip arrays. In the past, microarray-based transcriptomics studies have been successfully employed to gain insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the toxicity of chemicals7 as well as to identify molecular markers for their toxicities18. Advances in high throughput gene expression profiling, such as transcriptomics, microarray analysis can enlighten in a better understanding of the effects of toxic agents in biological systems.

Wang et al.19 reported phagocytosis of SiO2 into the lung causes inflammatory on the cascade resulting in fibroblast proliferation and migration followed by fibrosis associated with monocyte chemotactic protein 1 and sustaine increase in p53 and PUMA protein levels. Wang et al.19 interpreted involvement of MAPK and PI3K pathways in the SiO2− induced alteration of p53 and PUMA expression and to have possibility of link between SiO2-induced p53/PUMA expression in fibroblasts and cell migration on the basis of miRNAs that can interference with p53 and PUMA and prevent SiO2-induced fibroblast activation as well as migration. The study provide insight into the potential use of p53/PUMA in the development of novel therapeutic strategies for silicosis treatment. Therefore, in the current study we target to investigate the molecular mechanism underlying lung cell differentiation by identifying DEGs involved in silicosis, their expression (up/down-regulation), produce the possible network and gene ontology term analysis namely biological pathway and biological process for differentially expressed genes. We have also considered for identification of transcription factors (TFs) and microRNA (miRNA) associated with these DEGs for the regulation of the disease gene. A common network construction combining the relevant of TFs, miRNA, gene network, and small molecules for regulation of the disease progress is targeted.

Methodology

Microarray datasets

In this study, we have considered the work “Mechanisms of crystalline silica-induced pulmonary toxicity revealed by global gene expression profiling” and Dataset GSE30180 from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo)16. Datasets GSE30180 contains information regarding clinical tissues of human lung epithelial cells (A549 cells) considering 10 samples (5 control and 5 crystalline silica exposed to 800 ug/ml for 6 h using differential gene expression profile induced by silica conducted by National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health USA16). We have considered the available maximum concentration (800 ug/ml) from the study considering general worker’s shift exposure time period to have an idea at extreme conditions. Quality Control assessment of data quality is a major concern in microarray analysis. arrayQualityMetrics20 is from Bioconductor package that provides a report with diagnostic plots for one or two colour microarray data are used.

We have used arrayQualityMetrics for data quality assessment of microarray data and Quality Control is performed to identify potential low-quality arrays. The removal of low-quality arrays is desirable to avoid negative impact in downstream analysis procedures, by introducing invalid information and ultimately impairing statistical and biological significance. Array quality is assessed through the computation of commonly used statistical measures arrayQualityMetrics, an R package for quality control and quality assessment analysis that supports different types of microarrays in R. Here, we use an additional QC/QA that provides an HTML report with interactive plots. The instensity distribution of the arrarys of each box correspeonds to one array which indicated the over all quatity of each array with other corresponds are goods (Figure S1, S2).

Screening of differentially expressed genes

To screen DEGs between control and crystalline silica exposed cell, differential expression analysis is conducted using Bioconductor. Bioconductor operates in R (a statistical computing environment) and is applied for genomic data analysis and comprehension. The normalized data is analysed for identification of DEGs by limma package 3.26.8 in R (following adjust = “fdr” sort by B”, number 250). The robust MultiArray average method21 is applied to perform background correction and data normalization using default parameters in the limma package22. Subsequently, a differential analysis between silica exposed and the no silica exposed is performed using the limma package22, a modified version of the standard t-test incorporating the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) multiple hypotheses correction technique23. DEGs are defined as the false discovery rate (FDR) set as the cut‑off parameters to screen out 250 significant increases or decreases in gene expression levels24.

Identification of transcription factor

IRegulon plugin25 in Cytoscape (version 3.8.0)26 is used to detect transcription factors using motif2TF and their optimal sets of direct targets for a set of genes Chip-seq data. The minimum identity between orthologous genes is 0.05%, while the maximum FDR on motif similarity is 0.001. The normalized enrichment score (NES) > 5 is considered as a threshold value for the selection of potential relationships. The NES for a given motif/track is computed as the Area Under the Recovery Curve (AUC) value of the motif/track minus the mean of all AUCs for all motifs (or tracks), and divided by the standard deviation of all AUCs. When the distribution of AUCs follows a normal distribution then the NES score is a z-score indicative of the significance. To maintain high accuracy of network inference large motif collections are collected from various species, and linking these to candidate human TFs via a motif2TF 25.

Identification of miRNA (microRNA) for regulation Silicosis

To identify targets, regulators and interactions of the molecular factors included in the deferential gene expressed network, we search for gene-miRNA target and cross-validation using microRNA Data Integration Portal (mirDIP)27 in 30 database sources such as BCmicrO, BiTargeting, CoMeTa, Cupid, DIANA, ElMMo3, GenMir + + , MAMI, MBStar, MirAncesTar, MirMAP, MirSNP, MirTar, Mirza-G, MultiMiTar, PACCMIT, PITA, PicTar, RNA22, RNAhybrid, RepTar, TargetRank, TargetScan, TargetSpy, miRDB, miRTar2GO, miRcode, microrna.org, mirCoX and miRbase for regulating the expressions using both unidirectional and bidirectional search method. All the database considered in the present study is from authenticated and publically available sites27.

Functional enrichments analysis

ClueGO and CluePedia28 plug-in of Cytoscape is used for functional enrichment analysis. ClueGO plug-in translates functionally grouped Gene Ontology (GO) and pathway annotation networks with a hypergeometric test along with the kappa coefficient28 of pathways as well as functional correlations among pathways. ClueGO provides enrichment scores for selected gene sets against the user-provided gene list. CluePedia29 finds new markers that are potentially related with pathways and extend ClueGO functionality with other biological data deriving screened results. Default parameters are used, and only GO terms with P < 0.05 are selected in ClueGO with a Benjamini–Hochberg correction and a kappa score of 0.5 (medium).

Network construction and analysis of clusters

Finally, regulatory networks are constructed for silicosis by merging selected DEGs and TFs-DEGs pairs using Cytoscape. Thereafter, the Molecular Complex Detection (MCODE) plug-in23 is used to screen Clusters of hub genes from the network with degree cut-off = 10, haircut on, node score cut-off = 0.2, k-core = 2, and max. depth = 100.

Prediction of small-molecule signatures considering DEGs of silicosis

L1000CDS2 web tool is used for prediction of the potential small-molecule signature that matches user input signature genes expressions based on characteristic direction method in the underlying dataset. It is an ultra-fast LINCS L1000 Characteristic Direction Search Engine for prediction the potential small-molecule signature30 and DEGs are pasted into up/down text box and the top 50 signatures are considered.

Results and discussion

Identification of differentially expressed genes

The considered dataset is applied for significant DEGs identification by Bioconductor and 235 DEGs are found to be significantly associated with silicosis disease on the basis of the considered criteria. Table 1a, b enlist total of 235 DEGs, where down-regulated genes and up-regulated genes are 150 and 85 nos, respectively. On the basis of important pathway analysis and GO term Sellamathu et al.16 identified 60 DEGs for crystalline silica exposure in their study.

Table 1.

DEGs gene in Silicosis.

| Sl. no | Symbol | logFC | P value | Sl. no | Symbol | logFC | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Down-expression | |||||||

| 1 | LTB | − 0.3411 | 3.38E−07 | 76 | MYC | − 1.1121 | 3.18E−08 |

| 2 | CDCP1 | − 0.3691 | 1.25E−07 | 77 | EIF1 | − 1.1267 | 2.77E−07 |

| 3 | ABL2 | − 0.4115 | 1.53E−07 | 78 | CITED4 | − 1.133 | 4.62E−10 |

| 4 | EEA1 | − 0.415 | 1.07E−07 | 79 | C16orf72 | − 1.1369 | 2.89E−10 |

| 5 | SERPINB8 | − 0.4776 | 6.51E−08 | 80 | PMP22 | − 1.1442 | 2.10E−08 |

| 6 | ZC3H12A | − 0.4998 | 8.23E−08 | 81 | CDKN1A | − 1.215 | 3.91E−08 |

| 7 | ABTB2 | − 0.5189 | 9.46E−08 | 82 | FOSL1 | − 1.2205 | 2.31E−09 |

| 8 | KLF10 | − 0.5365 | 9.83E−08 | 83 | TRIM8 | − 1.2315 | 2.95E−08 |

| 9 | IL1B | − 0.5375 | 1.99E−07 | 84 | DDIT4 | − 1.2323 | 1.38E−08 |

| 10 | ELF3 | − 0.5526 | 2.55E−07 | 85 | AEN | − 1.2672 | 2.30E−08 |

| 11 | UBAP1 | − 0.5561 | 9.97E−08 | 86 | MCL1 | − 1.2687 | 1.50E−08 |

| 12 | SLC25A25 | − 0.5606 | 1.19E−07 | 87 | SERPINE1 | − 1.3011 | 4.86E−08 |

| 13 | TP53BP2 | − 0.5608 | 6.30E−08 | 88 | SOD2 | − 1.3201 | 1.41E−11 |

| 14 | NAV3 | − 0.569 | 4.66E−08 | 89 | C3orf52 | − 1.3231 | 6.38E−10 |

| 15 | KLHL21 | − 0.572 | 5.85E−09 | 90 | F2RL1 | − 1.3284 | 3.64E−08 |

| 16 | ZBTB20 | − 0.5817 | 8.21E−08 | 91 | NRG1 | − 1.3386 | 1.43E−08 |

| 17 | CD274 | − 0.5835 | 7.31E−08 | 92 | FRMD6 | − 1.3479 | 3.62E−10 |

| 18 | SH3KBP1 | − 0.5872 | 3.49E−08 | 93 | NOCT | − 1.3675 | 3.50E−07 |

| 19 | TEX10 | − 0.5877 | 4.32E−08 | 94 | CLCF1 | − 1.374 | 8.16E−10 |

| 20 | TUBB2B | − 0.5894 | 1.71E−07 | 95 | BTG1 | − 1.3812 | 2.45E−07 |

| 21 | HIST1H4H | − 0.5987 | 9.47E−08 | 96 | IL1A | − 1.388 | 6.36E−11 |

| 22 | EREG | − 0.6072 | 1.15E−08 | 97 | ERRFI1 | − 1.4065 | 1.00E−08 |

| 23 | HIST1H4B | − 0.6251 | 1.14E−09 | 98 | HIST2H2AA3 | − 1.4396 | 2.32E−08 |

| 24 | HIST1H2BD | − 0.637 | 5.37E−08 | 99 | PDK4 | − 1.4875 | 3.06E−07 |

| 25 | SPRY4 | − 0.6452 | 7.90E−09 | 100 | TIPARP | − 1.5105 | 9.14E−11 |

| 26 | MNT | − 0.6567 | 4.76E−09 | 101 | EFNA1 | − 1.5507 | 1.79E−08 |

| 27 | ZNF787 | − 0.6587 | 3.67E−08 | 102 | HES1 | − 1.5686 | 8.80E−09 |

| 28 | TNFRSF10A | − 0.6637 | 2.62E−07 | 103 | DUSP1 | − 1.5838 | 3.65E−11 |

| 29 | VPS37B | − 0.666 | 1.74E−08 | 104 | BHLHE40 | − 1.6055 | 1.92E−09 |

| 30 | PPP3R1 | − 0.6884 | 4.75E−08 | 105 | TRIB3 | − 1.6163 | 3.24E−09 |

| 31 | PPARG | − 0.7212 | 1.64E−07 | 106 | CSRNP1 | − 1.6418 | 2.52E−10 |

| 32 | SNAI2 | − 0.7478 | 2.92E−07 | 107 | JUND | − 1.707 | 3.89E−11 |

| 33 | HIST1H2BK | − 0.7562 | 2.39E−07 | 108 | NFKBIZ | − 1.7252 | 7.40E−10 |

| 34 | BRD2 | − 0.7742 | 5.13E−08 | 109 | ZFP36L1 | − 1.733 | 2.30E−07 |

| 35 | SLC25A37 | − 0.7751 | 7.63E−08 | 110 | CXCL5 | − 1.7693 | 4.87E−11 |

| 36 | CITED2 | − 0.7784 | 1.58E−08 | 111 | HBEGF | − 1.7961 | 1.48E−12 |

| 37 | RASD1 | − 0.7834 | 5.28E−10 | 112 | SMOX | − 1.8185 | 3.67E−09 |

| 38 | EPAS1 | − 0.7965 | 1.70E−08 | 113 | SOX9 | − 1.8386 | 3.29E−10 |

| 39 | RELB | − 0.7966 | 2.62E−09 | 114 | ETS1 | − 1.8392 | 1.59E−10 |

| 40 | HIST2H2AC | − 0.8065 | 3.30E−08 | 115 | CEBPB | − 1.8569 | 4.29E−10 |

| 41 | MYEOV | − 0.8132 | 1.55E−08 | 116 | ARID5B | − 1.8615 | 4.60E−10 |

| 42 | VGF | − 0.8144 | 1.93E−08 | 117 | RND3 | − 1.8847 | 9.85E−09 |

| 43 | ZNF296 | − 0.8163 | 2.07E−07 | 118 | CSF2 | − 1.9288 | 1.13E−11 |

| 44 | PHLDA2 | − 0.8249 | 2.43E−09 | 119 | GADD45A | − 1.93 | 2.46E−10 |

| 45 | ZNF34 | − 0.8412 | 1.81E−07 | 120 | MMP10 | − 1.9343 | 2.46E−11 |

| 46 | SDC4 | − 0.8467 | 2.17E−08 | 121 | TRIB1 | − 1.9631 | 5.73E−10 |

| 47 | NPC1 | − 0.8749 | 2.46E−08 | 122 | SOWAHC | − 2.0047 | 2.17E−09 |

| 48 | FOXQ1 | − 0.8766 | 1.73E−07 | 123 | DDIT3 | − 2.0533 | 2.47E−11 |

| 49 | SEMA4B | − 0.9049 | 4.29E−08 | 124 | CCL20 | − 2.055 | 4.35E−09 |

| 50 | TSC22D1 | − 0.9076 | 1.84E−08 | 125 | NFKBIA | − 2.1639 | 3.84E−12 |

| 51 | ODC1 | − 0.9077 | 3.40E−10 | 126 | SERTAD1 | − 2.1667 | 5.24E−11 |

| 52 | ID3 | − 0.9131 | 1.81E−07 | 127 | FST | − 2.2029 | 1.82E−11 |

| 53 | CCNL1 | − 0.9141 | 3.46E−08 | 128 | IL11 | − 2.2994 | 5.24E−11 |

| 54 | HAS2 | − 0.9215 | 7.31E−10 | 129 | NR4A2 | − 2.3141 | 9.86E−11 |

| 55 | ITPRIP | − 0.922 | 1.23E−08 | 130 | PHLDA1 | − 2.3232 | 5.65E−10 |

| 56 | HES4 | − 0.9358 | 1.66E−10 | 131 | TNFAIP3 | − 2.3238 | 6.14E−12 |

| 57 | KCNF1 | − 0.95 | 2.37E−07 | 132 | TMEM158 | − 2.3369 | 7.44E−12 |

| 58 | PIM1 | − 0.9635 | 1.97E−07 | 133 | STC1 | − 2.4343 | 5.40E−14 |

| 59 | CREBRF | − 0.9638 | 5.34E−08 | 134 | GEM | − 2.7581 | 1.41E−10 |

| 60 | FOXD1 | − 0.971 | 1.84E−08 | 135 | KLF6 | − 2.7745 | 4.91E−12 |

| 61 | TICAM1 | − 0.9763 | 2.72E−10 | 136 | IRAK2 | − 2.8376 | 5.47E−11 |

| 62 | DDX10 | − 0.9801 | 2.20E−09 | 137 | IER3 | − 2.9841 | 8.31E−13 |

| 63 | ZNF143 | − 0.9831 | 2.08E−07 | 138 | DUSP5 | − 3.0033 | 4.70E−12 |

| 64 | TSC22D2 | − 0.9901 | 1.97E−08 | 139 | CXCL2 | − 3.0447 | 4.31E−13 |

| 65 | CLK1 | − 0.9959 | 7.49E−08 | 140 | BIRC3 | − 3.0477 | 4.14E−14 |

| 66 | EHD1 | − 1.0058 | 1.26E−09 | 141 | IL6 | − 3.09 | 4.80E−14 |

| 67 | RYBP | − 1.0184 | 2.31E−08 | 142 | GDF15 | − 3.2752 | 5.89E−14 |

| 68 | STC2 | − 1.0209 | 2.01E−07 | 143 | JUN | − 3.4108 | 8.15E−13 |

| 69 | TMEM156 | − 1.037 | 4.80E−08 | 144 | ZFP36 | − 3.4123 | 6.61E−11 |

| 70 | FBXO32 | − 1.0608 | 5.93E−09 | 145 | PPP1R15A | − 3.4502 | 5.73E−14 |

| 71 | PTHLH | − 1.0665 | 2.10E−10 | 146 | PTGS2 | − 3.9915 | 1.10E−12 |

| 72 | AGO2 | − 1.0675 | 6.71E−09 | 147 | FOS | − 4.3462 | 1.87E−12 |

| 73 | ISG20 | − 1.0961 | 3.05E−10 | 148 | FOSB | − 5.118 | 7.37E−15 |

| 74 | PLAUR | − 1.098 | 3.53E−10 | 149 | EGR1 | − 5.1837 | 7.67E−15 |

| 75 | SERTAD2 | − 1.104 | 2.80E−09 | 150 | CXCL8 | − 5.3785 | 7.60E−17 |

| (b) Up-expression | |||||||

| 1 | MAT2A | 1.9868 | 8.29E−09 | 44 | MUM1 | 0.6787 | 7.56E−08 |

| 2 | TNS3 | 1.4299 | 4.96E−08 | 45 | AFAP1L2 | 0.6772 | 3.33E−10 |

| 3 | FZD2 | 1.3399 | 3.41E−08 | 46 | RSPRY1 | 0.6733 | 7.20E−08 |

| 4 | BAAT | 1.173 | 2.88E−10 | 47 | FAM120B | 0.666 | 1.13E−07 |

| 5 | SRSF5 | 1.1311 | 2.43E−08 | 48 | IDH1 | 0.6532 | 3.22E−07 |

| 6 | KIF20A | 1.1296 | 8.54E−10 | 49 | STK36 | 0.6508 | 1.52E−07 |

| 7 | MIR503HG | 1.0687 | 2.56E−08 | 50 | OIP5 | 0.6505 | 6.00E−08 |

| 8 | FAM83D | 1.0517 | 2.22E−08 | 51 | SUOX | 0.6391 | 1.59E−08 |

| 9 | PDXK | 1.0353 | 5.96E−08 | 52 | PHLDB1 | 0.6384 | 8.64E−08 |

| 10 | FAM217B | 1.0242 | 9.44E−09 | 53 | AP3M2 | 0.634 | 2.75E−08 |

| 11 | MED20 | 1.0059 | 2.15E−08 | 54 | CKAP2 | 0.6166 | 4.08E−08 |

| 12 | CENPF | 0.9756 | 1.14E−08 | 55 | C17orf58 | 0.6126 | 6.55E−08 |

| 13 | TMEM203 | 0.9476 | 3.90E−08 | 56 | LGR4 | 0.6104 | 6.92E−08 |

| 14 | CPSF4 | 0.9226 | 1.37E−08 | 57 | RNFT2 | 0.6083 | 1.46E−07 |

| 15 | MSRB1 | 0.9176 | 2.00E−07 | 58 | MCEE | 0.5906 | 8.08E−08 |

| 16 | EPDR1 | 0.9021 | 5.20E−08 | 59 | ZNF30 | 0.5901 | 2.43E−07 |

| 17 | GEMIN6 | 0.8992 | 1.65E−07 | 60 | PHF21A | 0.5889 | 2.24E−07 |

| 18 | HSPA2 | 0.8958 | 3.12E−08 | 61 | FAM64A | 0.5868 | 1.58E−07 |

| 19 | PDE7B | 0.8926 | 1.33E−08 | 62 | NREP | 0.5857 | 1.20E−07 |

| 20 | LACTB | 0.8845 | 1.37E−08 | 63 | OGT | 0.5782 | 1.18E−07 |

| 21 | ANG | 0.8734 | 3.98E−08 | 64 | FANCL | 0.5766 | 1.19E−07 |

| 22 | TMEM2 | 0.8729 | 5.82E−09 | 65 | ZBED8 | 0.561 | 3.45E−08 |

| 23 | MALSU1 | 0.8366 | 1.34E−07 | 66 | KLHL12 | 0.5563 | 8.06E−09 |

| 24 | RAB40B | 0.8208 | 1.70E−07 | 67 | GMCL1 | 0.5349 | 2.89E−07 |

| 25 | IMP3 | 0.8158 | 5.93E−08 | 68 | CCDC117 | 0.5166 | 3.28E−07 |

| 26 | SKP2 | 0.7971 | 3.97E−09 | 69 | ANKRA2 | 0.5163 | 1.73E−07 |

| 27 | GID8 | 0.7961 | 1.26E−07 | 70 | CBX2 | 0.5119 | 5.66E−08 |

| 28 | GSPT2 | 0.7938 | 8.55E−08 | 71 | CCDC25 | 0.5029 | 2.14E−07 |

| 29 | HOXC8 | 0.7813 | 1.93E−07 | 72 | TIA1 | 0.5002 | 8.52E−08 |

| 30 | TOP2A | 0.7797 | 1.84E−07 | 73 | AGGF1 | 0.4931 | 2.06E−07 |

| 31 | DCBLD1 | 0.7778 | 6.79E−08 | 74 | NUPL2 | 0.4768 | 1.63E−07 |

| 32 | CDCA8 | 0.7776 | 6.30E−08 | 75 | CCDC34 | 0.4618 | 1.46E−07 |

| 33 | CXXC5 | 0.7511 | 1.01E−07 | 76 | THNSL1 | 0.4595 | 1.86E−07 |

| 34 | UNC50 | 0.7461 | 2.13E−07 | 77 | SNUPN | 0.4576 | 1.52E−07 |

| 35 | OARD1 | 0.7395 | 3.17E−07 | 78 | MAGEE1 | 0.4561 | 1.55E−07 |

| 36 | POC1A | 0.7372 | 7.79E−08 | 79 | ASB13 | 0.4215 | 3.36E−07 |

| 37 | AURKA | 0.7346 | 3.10E−07 | 80 | PXYLP1 | 0.4214 | 7.53E−08 |

| 38 | HNRNPA0 | 0.7228 | 2.46E−09 | 81 | AXIN2 | 0.4176 | 1.65E−07 |

| 39 | RBM4B | 0.7161 | 1.61E−07 | 82 | RNASE4 | 0.4174 | 3.70E−08 |

| 40 | C1orf131 | 0.7144 | 3.04E−08 | 83 | CDK19 | 0.4174 | 1.95E−07 |

| 41 | TSEN2 | 0.7092 | 2.24E−07 | 84 | ZNF17 | 0.4124 | 3.44E−07 |

| 42 | ZNF512 | 0.7006 | 2.02E−07 | 85 | CDH1 | 0.3405 | 2.50E−07 |

| 43 | SLC35E3 | 0.6925 | 9.92E−08 | ||||

Identification of transcription factors (TFs) for differentially expressed genes

Adopting the iRegulon plugin in Cytoscape, 24 TFs are identified from publicly available database signatures/genesets (GeneSigDB, Ganesh clusters or/and MSigDB) that are significantly associated with the DEGs involved in the silicosis disease. It is found that 20 TFs influence both up and down-expressed genes whereas four TFs are solely involved in controlling only the down-regulated genes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Identified TFs for regulation DEGs genes in Silicosis.

| Sl. no | TF | Target gene with expressions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CHD1 | Up | A34A1:A25 |

| Down | CEBPB, PPP1R15A, DUSP1, DUSP5, FOSB, FOSL1, MCL1, KLF10, JUN, CDKN1A, JUND, ATF3, NR4A2, SOD2, FOS, SOX9, RELB, ERRFI1, SNAI2, TP53, SERPINE1, EGR1, STC2, CSRNP1IL6, RND3, ETS1, EIF1, PIM1, DDIT3, TP53BP2, ELF3, TSC22D1, TSC22D2, KLHL21 | ||

| 2 | ATF4 | Up | NA |

| Down | FOSB, ATF3, CDKN1A, JUN, FOSB, ERRFI1, EIF1, DDIT4, CEBPB, TRIB3, CCL20, HAS2, PPARG, DDIT3, STC2, IL1A | ||

| 3 | BACH1 | Up | BAAT, OGT, PHF21A, CXXC5, EPDR1 |

| Down | FOSB, FOSL1, DUSP1, DUSP5, NR4A2, CDKN1A, IL6, CEBPB, SOD2, PPARG, ATF3, SOX9, HAS2, RELB, ERRFI1, RND3, ETS1, PIM1, IL1A, DDIT3, STC2, SERPINE1, TSC22D1, TSC22D2, TRIB3, EEA1, CSF2, BIRC3, PTGS2, TNFAIP3, CITED2, CSRNP1, F2RL1, KLHL21, EREG, CXCL2, SERTAD1, PTHLH, HBEGF | ||

| 4 | CEBPG | Up | CXXC5, OGT, CENPF, GEMIN6, PHF21A, SLC35E3, BAAT, CDK19, EPDR1, FAM83D, MED20, CBX2 |

| Down | ATF3, CDKN1A, ERRFI1, RND3, ETS1, DDIT3, DDIT4, SNAI2, SERPINE1, EGR1, STC2, TSC22D2,TSC22D1, TRIB3, HAS2, IL1A, EEA1, CSF2, PTGS2, TNFAIP3, CXCL2, PPARG, CSRNP1, KLHL21, EREG, CEBPB, PPP1R15A, SOX9, PPP3R1, NR4A2, EIF1, DUSP1, FOS, FOSB, FOSL1, MCL1, KLF10, JUN, JUND, IL6, NR4A2 RELB,, PTHLH, NFKBIA, BIRC3, HIST1H2BD, CITED2 | ||

| 5 | KAT2A | Up | TMEM203 |

| Down | FOS, FOSB, FOSL1, DUSP5, MCL1, CDKN1A, KLF10, NR4A2, JUN, SOD2, JUND, ERRFI1, ATF3, EIF1, PIM1, DDIT4, EGR1, TSC22D1, HIST1H2BD | ||

| 6 | PAX3 | Up | NA |

| Down | FOS, FOSB, NR4A2, FOSL1, RELB, PPARG, KLF10, ERRFI1, EIF1, EGR1, RND3, TSC22D2, HAS2, PTHLH, PPP1R15A, TP53BP2, ATF3, FOSB, CDKN1A, IL6 | ||

| 7 | FOXF1 | Up | BAAT, PHF21A, CXXC5, CDH1, CDK19 |

| Down | FOSB, FOSL1, DUSP5, KLF10, IL6, CDKN1A, PPP1R15A, KLF10, JUND, NR4A2, SOX9, ERRFI1, TNF, RND3, ETS1, EIF1, DDIT4, ELF3, SERPINE1, EGR1, STC2, TRIB3, CEBPB, HAS2, EEA1, CSF2, BIRC3, CITED2, F2RL1, KLHL21, CXCL2, PTHLH, NFKBIA, HBEGF, HIST1H2BD, RELB, PPP3R1 | ||

| 8 | CREB3 | Up | CXXC5, CDK19, CENPF |

| Down | DUSP1, FOS, FOSB, DUSP5, JUND, NR4A2, CDKN1A, JUN, ATF3, EIF1, IL6, SOX9, HAS2, EGR1, PPP1R15A, RELB, TNFAIP3, CITED2, KLHL21, PTHLH, STC2, HIST1H2BD, ERRFI1, IL1A, TSC22D2, CEBPB, PPARG, PPP3R1, HBEGF | ||

| 9 | POLR2A | Up | NA |

| Down | FOS, FOSB, MCL1, NR4A2, JUND, PPP1R15A, DUSP1, JUN, EIF1, DDIT3, EREG, HIST1H2BD, EGR1 | ||

| 10 | HOMEZ | Up | CDK19, CENPF, CXXC5, OGT |

| Down | ATF3, NR4A2, ETS1, PIM1, CDKN1A, PPARG, PPP3R1, TP53BP2, CSRNP1 | ||

| 11 | CEBPB | Up | PHF21A, OGT |

| Down | KLF10, NR4A2, ATF3, SOD2, PPP1R15A, CDKN1A, DDIT4, TRIB3, HAS2, IL1A, EREG, CXCL2, NFKBIA, HIST1H2BD, PPARG | ||

| 12 | ZNF513 | Up | PHF21A, CXXC5 |

| Down | FOS, FOSB, NR4A2, JUND, DDIT4, EGR1, TSC22D1, HAS2, TNFAIP3, ATF3, F2RL1, CDKN1A, TSC22D2, ERRFI1, PIM1, HIST1H2BD, CITED2, PPARG | ||

| 13 | E2F1 | Up | PHF21A, CXXC5 |

| Down | ATF3, DUSP5, NR4A2, SOX9, IL6, ERRFI1, RND3, ETS1, PIM1, TSC22D1, HAS2, BIRC3, PTGS2, TNFAIP3, F2RL1, TSC22D2 | ||

| 14 | EGR2 | Up | RELA, |

| Down | FOS, NR4A2, CDKN1A, ETS1, PIM1, EGR1, HAS2, PTHLH | ||

| 15 | FOXM1 | Up | FAM83D, CENPF, CXXC5, KIF20A, TOP2A, RNFT2, ASB13, AURKA, OIP5, CDK19, CDH1, CDCA8 |

| Down | FOS, KLF10, SOX9, PIM1, ELF3, STC2, TSC22D2, CITED2, EREG, HIST1H2BD, C3orf52 | ||

| 16 | ZNF683 | Up | PHF21A, CXXC5 |

| Down | FOS, JUND, NR4A2, CDKN1A, DDIT4, HAS2, SERTAD1, PTHLH, ERRFI1, STC2, ATF3 | ||

| 17 | RELA | Up | OGT, PHF21A, EPDR1, CXXC5, KIF20A, CBX2, GEMIN |

| Down | FOSB, DUSP5, NR4A2, CDKN1A, IL6, ATF3, CSRNP1, JUND, SOX9, TP53, CSF2, HAS2, PPARG, PTHLH, DDIT4, BIRC3, TNFAIP3, CITED2PIM1, ETS1, STC2, SERPINE1, EGR1, TSC22D1, CCL20, CENPF, ERRFI1, TNF, RND3, EIF1, F2RL1, EREG, NFKBIA, HBEGF, HIST1H2BD, PPP3R1 | ||

| 18 | MEF2D | Up | CXXC5, BAAT, PHF21A, OGT |

| Down | ATF3, JUND, PPP1R15A, FOSB, NR4A2, CEBPB, SOX9, TNF, CDKN1A, HAS2, ELF3, EGR1, PTHLH, RELB, ERRFI1, EIF1, DDIT4, TRIB3, SERPINE1 | ||

| 19 | FOXP2 | Up | PHF21A, CDK19, FAM83D |

| Down | FOSB, FOSL1, DUSP5, KLF10, JUND, ATF3, DUSP1, CDKN1A, CSRNP1, JUN, F2RL1, CITED2, SOD2, ERRFI1, EEA1, ETS1, EIF1, PIM1, DDIT3, STC2, EGR1, DDIT4, TP53BP2, PPP3R1, TSC22D2, CEBPB, TRIB3, KLHL21, SERTAD1, HBEGF | ||

| 20 | PSMC2 | Up | CXXC5 |

| Down | KLF10, NR4A2, CDKN1A, EIF1, ETS1, NFKBIA | ||

| 21 | JUND | Up | NA |

| Down | FOSL1, NR4A2, CSRNP1, SOX9, PPARG, ERRFI1, DDIT4, EGR1, TSC22D1, DDIT3, CITED2, F2RL1, EREG, PTHLH, HIST1H2BD | ||

| 22 | ESR1 | Up | FAM83D |

| Down | ATF3, CDKN1A, CSRNP1, ETS1, CCL20, NFKBIA, | ||

| 23 | TBPL2 | Up | PHF21A, CDH1, CXXC5, BAAT |

| Down | ATF3, FOSB, DUSP5, NR4A2, JUND, FOS, SOX9, ERRFI1, EGR1, STC2, EIF1, TSC22D1, CDKN1A, DDIT4, KLHL21, PTHLH, TNF | ||

| 24 | RDBP | Up | FAM83D, OIP5 |

| Down | ATF3, FOS, FOSL1, JUN, DUSP1, EIF1, DDIT3, DDIT4, EGR1, CITED2, HIST1H2BD | ||

Identification of miRNA for DEGs from database-driven expansion of the network

Using CyTargetLinker31 authors observed initially only 2716 miRNAs responsible for silicosis affected gene regulation from databases as mentioned in the methodology. Therefore, the authors further explored a few other databases as mentioned in the methodology (public databases around 30 nos). We applied mirDIP and observed a total of 2586 miRNAs associated with targeted DEGs responsible for silicosis and categorized as “very high” (top 1%) and “high” (top 5% (excluding top 1%))27. A total of 1105 miRNA is categorized as very high where 846 miRNAs influence upregulated genes, 1055 miRNAs regulate down-regulated genes and 801 miRNAs regulates both (Supplementary file 1). For example, among identified miRNA, miRNA- 29 influences epithelial-mesenchymal transition32, and miRNA-489 can repress its target genes MyD88 and Smad3 responsible for silicosis33. Chen et al.34 reported the involvement of IL-10-producing B cells in the development of silica-induced lung inflammation and fibrosis of mice and many such in the list. Yang et al.35 observed significant genetic heterogeneity involved in the origin and development of silicosis from research data and recommended relevant miRNAs as biomarkers having a role in regulating pulmonary fibrosis. The research group reported differential miRNAs in leukocytes as up-regulated (18 nos.) and down-regulated (20 nos.) during silicosis, compared with the control group miR-19a in peripheral blood leukocyte35. Faxuanet al.36 observed 39 differential expression miRNAs (14 up-regulated and 25 down-regulated in silicosis sample) between silicosis and normal lung tissues. Zhang et al.37 performed genome-wide miRNAs expression profiling in BALF cell fraction of 3 silicosis observation stages simultaneously with 6 silicosis patients. Among the identified 110 dysregulated miRNAs having down-regulation trend, 23 miRNAs abundantly expressed in stage I and Stage II silicosis suggesting different stages of silicosis are associated with distinct changes in miRNAs expression.

Regulatory network construction

We identified targets, regulators and integrators of the molecular factors included in the DEG Network. Gene expressed network is a node and edge interaction between gene–gene or gene-miRNA and regulatory transcription factors. Precisely, we searched for gene regulatory interaction network as a) TF-target gene interactions and b) miRNA–gene interactions. We merged all the extracted interactions with the gene expressed Network using the same annotation principles as above.

TFs-DEGs network analysis

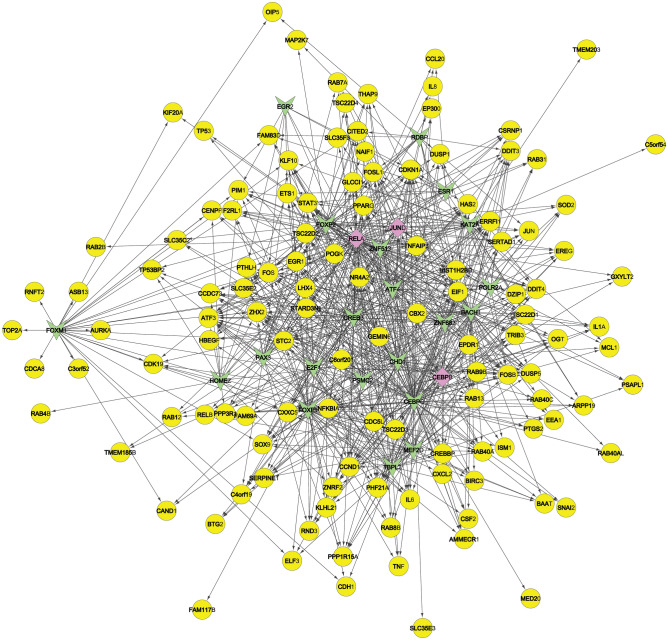

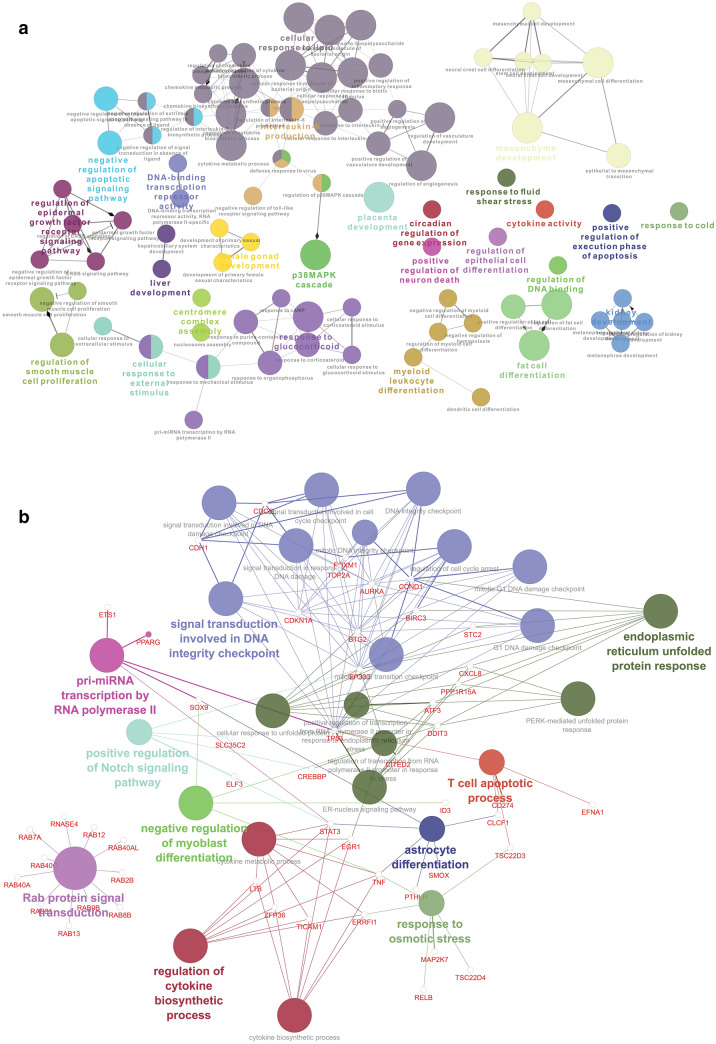

The interaction network is derived using plugin Cytoscape with 147 Nodes and 769 edges (Fig. 1). The blue nodes indicate here are the genes namely, RELA, JUND, and CEBPB which act simultaneously as TF, so function as both regulator and regulated gene.

Figure 1.

The gene-transcription factor regulation network. Notes: a round node represents a gene (yellow node) with differencial expresstion, a triangle nodes (green node) represents the TFs, and a rectangular rectangular nodes (pink node) represent the TFs that plays a role as regulator and regulated.

The most interacting TFs are CHD1, CEBPG, FOXF1, CREB3, RELA, and FOXP2, etc. as given in Table 2. The TF CHD1 is a gene similar to various other genes that act as TF and can regulate the activity of certain genes providing instructions to make epithelialcadherin or E-cadherin (a protein) having influence in cell adhesion, the transmission of chemical signals within cells, control of cell maturation and movement38. ATF4 TF is known to regulate memory, metabolism, and adaptation of cells to stress factors such as anoxic insult, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and oxidative stress39. In normal bronchial epithelial cells, CEBPG TF correlates with antioxidant and DNA to repair genes which is absent for individuals with bronchogenic carcinoma40. Expression of KAT2A(Tyr645Ala), reduces gene expression and inhibits tumor cell proliferation as well as tumor growth41. CREB3 influences leukocyte migration, tumor suppression, and endoplasmic reticulum stress-associated protein degradation42,43. PAX3 plays critical roles during fetal development as well as neural crest44,45. Mutations in paired boxgene 3 are associated with Waardenburg syndrome, craniofacial-deafness-handsyndrome, and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma46. FOXF1 promote slung regeneration after partial pneumonectomy and involved in murine vasculogenesis, lung, and foregut development. Mice with reduced levels of pulmonary FOXF1 may face death due to pulmonary hemorrhages with deficient alveolarization and vasculogenesis47,48. POLR2A geneis associated with poor overall and disease-free survival of patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer49. FOXP2 is responsible for defective postnatal lung alveolarization resulting in postnatal lethality in mice. T1 alpha, a lungalveolar epithelial type 1 cell-restricted gene crucial for lung developmentand function, is a direct target of FOXP2 and FOXP0. Both FOXP2 and FOXP1 are crucial regulators of lung and oesophageal development50. E2F1significantly influences S phase progression and apoptosis as well FOXM1 expression, cell survival, epirubicin resistance51 and its low level in primary lung adenocarcinoma may lead to cancer52. In small cell lung cancer, activation of oncogene EZH2 is often triggered by genomic deregulation of the E2F/Rb pathway53. Alveolar macrophages from RELA deficient animals are significantly less capable to involve in the canonical NF-κB pathway (a prototypical immune transcription pathway) and stimulate epithelial cells54.

miRNA regulatory network analysis

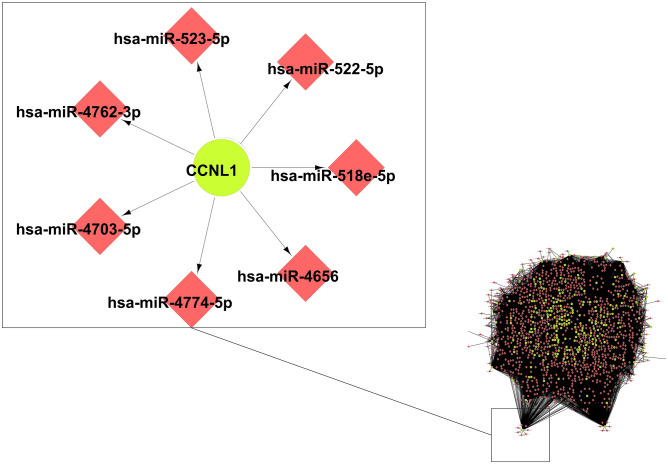

In present study, from the dataset GEO30180 we enlisted significant DEGs and investigated associated miRNAs using CyTargetLinker and in-silico validation for miRNA through cross validation with the multiple database mirDIP is carrird out for creation of Gene-TFs-miRNAs regulatory network. We have chosen the miRNA and mRNA from microRNA Data Integration Portal (mirDIP) web tools. In present manuscript, authors tried to identify the significant DEs, regulatory TFs and relevant miRNAs and predict the small molecules for drug combination of silicosis. Interaction network for genes and miRNAs is derived with 2461 Nodes and 13,343 edges as given in Fig. 2 using a plug-in CyTranslinker. An enlarged part is showing GPRY gene with its regulating miRNAs as an example. A grand total of 1100 number of very high target miRNA is identified from the considered database mirDIP using score class “very high”. For many upregulated genes, miRNA (numbers are given in parenthesis) is associated in several hundred; for example, CDK19 (617), OGT (552), LGR4 (426), MAT2A (409),NREP (408), TIA1 (387), and TMEM2 (202).

Figure 2.

Gene–miRNA interactions network; index red node (miRNA); grey node (gene).

Similarly, for down-regulated genes, a grand total of 1055 very high target miRNA is identified to be associated with theconsidered database mirDIP using score class “very high”. For example, RYBP (899), SERTAD2 (666), CREBRF (675), NAV3 (629), PPP3R1 (560), TSC22D2 (555), STC1 (523), MCL1 (463), EEA1(414), and ZFP36L1(387).

Integrating TF and miRNA regulatory networks

TFs induce micro RNAs (miRNAs) transcription and miRNAs influence mRNA translation as well as transcript degradation for the regulation of gene expression and all these results in complex relationships feedback or feed-forward loops54–56.

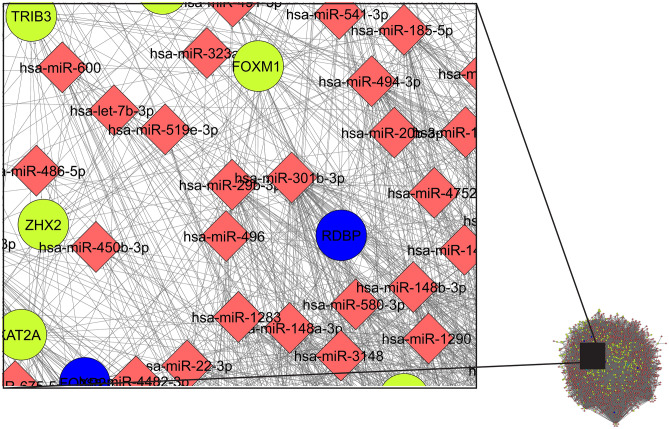

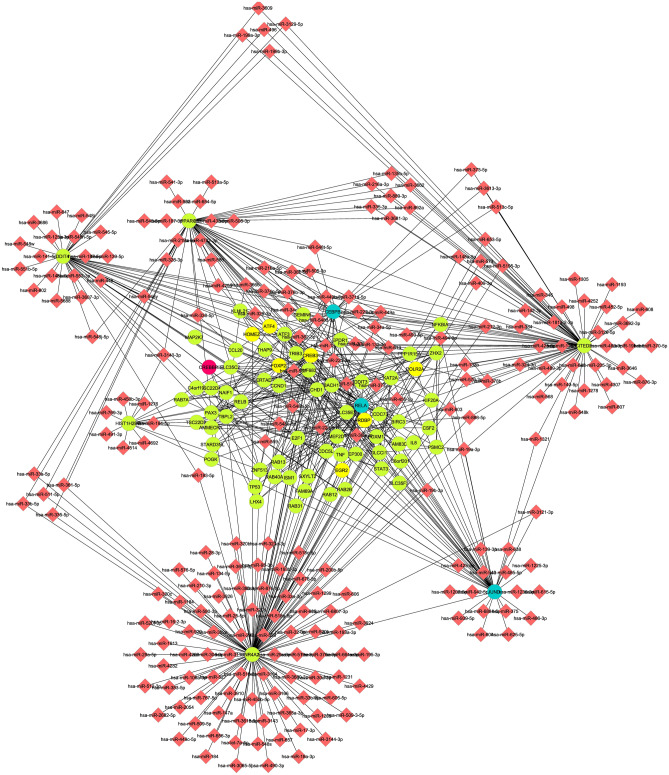

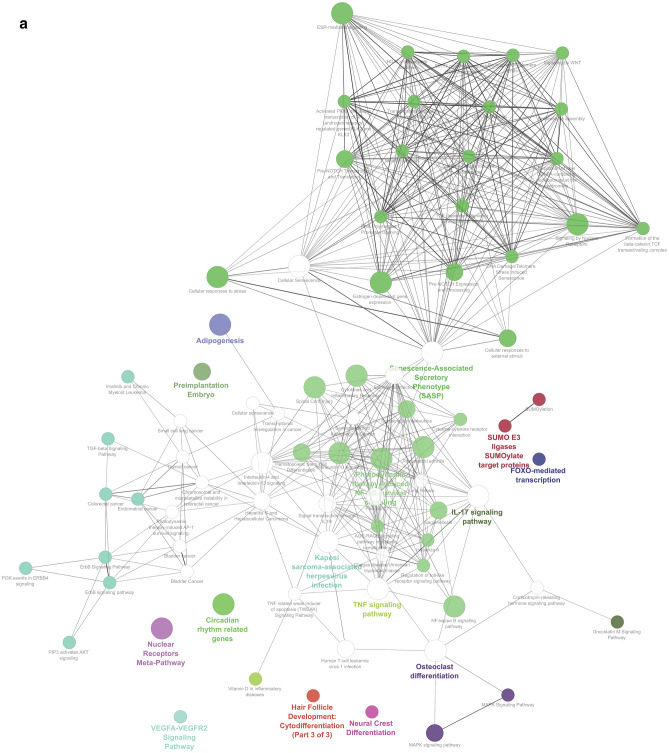

Furthermore, miRNAs and TFs are capable to alter each other's expression which results in difficulties for ascertaining the effect either one has on the target gene (TG) expression. The Integrated network (Fig. 3) consists of a total of 1396 nodes and edges 17,248 is constructed using Cytoscape from 235 (85 + 150) DE TGs, 24 regulating TFs and 1100 (846 up regulators + 1055 down regulators; 801 are common for both) very high target miRNA. In the network analysis, 14 clusters are achieved. The highest score of the cluster 1 is found to be 5.22 as given in Table 3. The present Gene-TFs-miRNAs regulatory network to find out the potential regulatory and regulated nodes provide detail insight for the gene associations, regulations by relevant TFs, and controlling the miRNAs.

Figure 3.

Gene–TF-miRNA regulatory network for Silicosis disease.

Table 3.

GO: biological process of Gene of all the clusters.

| GOID | GOTerm | Term P value | Nr. genes | Associated genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0032482 | Rab protein signal transduction | 9.73404E−12 | 11 | [RAB12, RAB13, RAB2B, RAB31, RAB40A, RAB40AL, RAB40C, RAB7A, RAB8B, RAB9B, RNASE4] |

| GO:0031570 | DNA integrity checkpoint | 2.18109E−05 | 9 | [AURKA, BTG2, CCND1, CDC5L, CDH1, CDKN1A, EP300, TOP2A, TP53] |

| GO:0030968 | Endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response | 1.3072E−05 | 8 | [ATF3, BIRC3, CCND1, CXCL8, DDIT3, EP300, PPP1R15A, STC2] |

| GO:0034620 | Cellular response to unfolded protein | 3.59987E−05 | 8 | [ATF3, BIRC3, CCND1, CXCL8, DDIT3, EP300, PPP1R15A, STC2] |

| GO:0042770 | Signal transduction in response to DNA damage | 4.69977E−05 | 8 | [AURKA, BTG2, CDC5L, CDH1, CDKN1A, EP300, FOXM1, TP53] |

| GO:0071156 | Regulation of cell cycle arrest | 1.24845E−05 | 8 | [AURKA, BIRC3, BTG2, CCND1, CDKN1A, EP300, FOXM1, TP53] |

| GO:0042107 | Cytokine metabolic process | 5.50804E−05 | 7 | [EGR1, ERRFI1, LTB, STAT3, TICAM1, TNF, ZFP36] |

| GO:0042089 | Cytokine biosynthetic process | 5.26779E−05 | 7 | [EGR1, ERRFI1, LTB, STAT3, TICAM1, TNF, ZFP36] |

| GO:0042035 | Regulation of cytokine biosynthetic process | 2.84863E−05 | 7 | [EGR1, ERRFI1, LTB, STAT3, TICAM1, TNF, ZFP36] |

| GO:0043618 | Regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter in response to stress | 9.16051E−05 | 7 | [ATF3, CITED2, CREBBP, DDIT3, EGR1, EP300, TP53] |

| GO:0072395 | Signal transduction involved in cell cycle checkpoint | 7.42013E−06 | 7 | [AURKA, BTG2, CDC5L, CDH1, CDKN1A, EP300, TP53] |

| GO:0044774 | Mitotic DNA integrity checkpoint | 6.56057E−05 | 7 | [AURKA, BTG2, CCND1, CDKN1A, EP300, TOP2A, TP53] |

| GO:0072401 | Signal transduction involved in DNA integrity checkpoint | 6.96437E−06 | 7 | [AURKA, BTG2, CDC5L, CDH1, CDKN1A, EP300, TP53] |

| GO:0072422 | Signal transduction involved in DNA damage checkpoint | 6.96437E−06 | 7 | [AURKA, BTG2, CDC5L, CDH1, CDKN1A, EP300, TP53] |

| GO:0006970 | Response to osmotic stress | 0.000105185 | 6 | [ERRFI1, MAP2K7, RELB, TNF, TSC22D3, TSC22D4] |

| GO:0048708 | Astrocyte differentiation | 0.000105185 | 6 | [CLCF1, PTHLH, SMOX, SOX9, STAT3, TNF] |

| GO:0044783 | G1 DNA damage checkpoint | 3.63554E−05 | 6 | [AURKA, BTG2, CCND1, CDKN1A, EP300, TP53] |

| GO:0044819 | Mitotic G1/S transition checkpoint | 3.41466E−05 | 6 | [AURKA, BTG2, CCND1, CDKN1A, EP300, TP53] |

| GO:0031571 | Mitotic G1 DNA damage checkpoint | 3.41466E−05 | 6 | [AURKA, BTG2, CCND1, CDKN1A, EP300, TP53] |

| GO:0045747 | Positive regulation of Notch signaling pathway | 0.000106301 | 5 | [CREBBP, ELF3, EP300, SLC35C2, STAT3] |

| GO:0061614 | Pri-miRNA transcription by RNA polymerase II | 3.54965E−05 | 5 | [ETS1, PPARG, SOX9, STAT3, TP53] |

| GO:0070231 | T cell apoptotic process | 8.59147E−05 | 5 | [CD274, CLCF1, EFNA1, TP53, TSC22D3] |

| GO:0006984 | ER-nucleus signaling pathway | 4.22636E−05 | 5 | [ATF3, CXCL8, DDIT3, PPP1R15A, TP53] |

| GO:0045662 | Negative regulation of myoblast differentiation | 5.55529E−05 | 4 | [DDIT3, ID3, SOX9, TNF] |

| GO:0036499 | PERK-mediated unfolded protein response | 3.16435E−05 | 4 | [ATF3, CXCL8, DDIT3, PPP1R15A] |

| GO:1990440 | Positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress | 8.34712E−05 | 3 | [ATF3, DDIT3, TP53] |

Extraction of the cluster network

Using MCODE we extracted total 14 clusters according to the score computed along with nodes and edges, in which only six possesses Gene-TFs-miRNA interactions. In cluster 1 with maximum score, there are mainly Gene–Gene-miRNA interactions. However, gene FOXQ1 is observed in the clusters which is also identified as TF in literature. Few clusters are found to have only gene–gene or gene-miRNA interaction over Gene-TFs or Gene-TFs-miRNA interaction and is given in Supplementary Table S1.

From Fig. 4 in cluster 3 (Nodes-312, Edges-621, Score = 3.968), for example, TF JUND is associated with various genes as well as numerous miRNAs altogether. A similar type of network is observed for TFs RELA and PEBPB. In present study, considering the data with crystalline silica exposure of 0 and 800 µg/mL for 6 h exposure, 235 DEGs are enlisted on the basis of FDR set as the cut‑off parameters to screen out 250 significant increases or decreases in gene expression levels. Previous study by Sellamatu et al.16 considered a set of exposure (0, 15, 30, 120, 240 µg/cm2 for 0–6 h) for their study and on the basis of potential pathway and gene ontology term identified significantly expressed 60 DEGs. Current study emphasise on identification and enlist of the biological pathway and process individually where identified DEGs are involved identifying potential regulating TFs and target miRNA according to the DEGs.

Figure 4.

Cluster 3 for Gene–TFs-miRNA regulatory network in Silicosis disease.

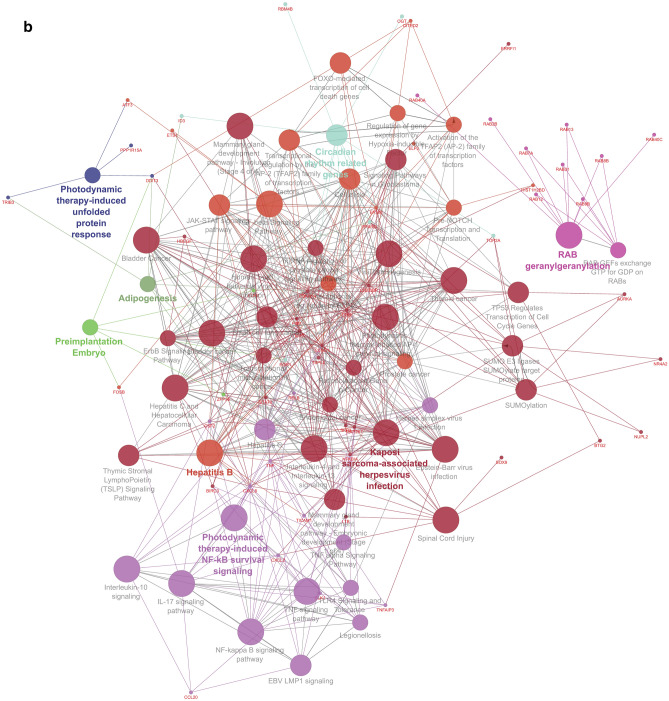

Functional enrichments analysis

In present study, biological processes and pathways involoving the 235 DEGs with silica exposure are evaluated and significant biological process with DEGs involved are given in Table 3. A maximum of 11 genes is responsible for Rab proteins signal transduction followed by 9 genes for DNA integrity checkpoint (Fig. 5a). Various researchers reported that overexpression of Rab GTPases have a striking relationship with carcinogenesis and dysregulation of Rab proteins can be linked to the progression of already existent tumors contributing to their malignancy57,58.

Figure 5.

(a) GO: Biological process of Gene involved in Silicosis disease. (b) GO: Biological process of Gene of all the clusters involved in Silicosis disease.

For Cluster 1, the biological process identified and the genes involved are biological adhesion (TNS3, CD274, and CDH1), biological phase (TOP2A), biological regulation (TOP2A, CD274), cellular process (TN53, IDH1, TOP2A, UBAP1, CD274, and CDH1), immune system process (TN53, CD274), metabolic process (IDH1, and UBAP1) and response to a stimulus (CD274) (Fig. 5b). The biological pathways observed in the study is shown in Fig. 6a,b. Major pathways with higher involvement of genes (numbers given in parenthesis) are Cytokines and Inflammatory Response (6), Rheumatoid arthritis (11), Signaling by Nuclear Receptors (14), NF-kappa B signaling pathway (10), Cellular responses to stress (21), Interleukin-4 and Interleukin-13 signaling (10), Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpes virus infection (13), Interleukin-10 signaling (8), TNF signaling pathway (13), Spinal Cord Injury (13), Circadian rhythm related genes (15), Nuclear Receptors Meta-Pathway (19), IL-17 signaling pathway (16), Cellular Senescence (20), Adipogenesis (11), ESR-mediated signaling (13), Photodynamic therapy-induced NF-kB survival signaling (9), Osteoclast differentiation (11), Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP) (13), and Estrogen-dependent gene expression (13).

Figure 6.

(a) GO: Biological pathways of Gene involved in Silicosis disease. (b) GO: Biological pathways of Gene from six clusters involved in Silicosis disease.

Biological pathway analysis of the genes from the six clusters having Gene-TF-miRNA interactions and found the maximum genes are involved in Human T-cell leukemia virus 1 infection as well as Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection (14 nos) followed by Hepatitis B (11 nos) [Supplementary Table (S2)].

Prediction Small molecule signatures

Table 4 displays the Rank (based on the synergy score), the perturbed molecule (names of the chemical perturbations), Dose, Cell-line, time, the direction of regulation, and the GEO ID from which thesignature is extracted. We next sought to predict the drug combination with the ranked small molecule drug signature list (Table 5). From L1000CDS2 search engine forgene-set search, for differentially expressed genes provided nearly fifty significant combinations. These help infinding reverse and mimic combinations of an input gene expression signature for controlling Silicosis. The maximum scoring small-molecule combinations are CGP-60774 (total 20 combinations) followed by alvocidib (total 15 combinations) and with AZD-7762 (total 24 combinations) as can be seen from Table 5 with a few other drugs having a high probability of success.

Table 4.

Drug signature predicted at each time point.

| Time | Cell-line | Rank | Score | Perturbation | Dose (um) | Time (j) | Cell-line | Rank | Score | Perturbation | Dose (um) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 h | HME1 | 1 | 0.236 | CGP-60474 | 0.12 | 3 | HS578T | 10 | 0.1798 | CGP-60474 | 0.37 |

| 2 | 0.2303 | Alvocidib | 3.33 | 13 | 0.1798 | BMS-387032 | 1.11 | ||||

| 3 | 0.2135 | CGP-60474 | 0.04 | 16 | 0.1742 | CGP-60474 | 3.33 | ||||

| 4 | 0.1966 | A443654 | 1.11 | 25 | 0.1685 | Alvocidib | 10 | ||||

| 5 | 0.1966 | Alvocidib | 1.11 | 29 | 0.1629 | PF-431396 | 10 | ||||

| 6 | 0.1966 | Alvocidib | 0.37 | 31 | 0.1629 | BMS-387032 | 3.33 | ||||

| 8 | 0.191 | Alvocidib | 0.12 | 25 | 0.1685 | Alvocidib | 10 | ||||

| 9 | 0.1854 | PF-562271 | 10 | 29 | 0.1629 | PF-431396 | 10 | ||||

| 11 | 0.1798 | CGP-60474 | 3.33 | 44 | 0.1517 | WZ-3105 | 10 | ||||

| 12 | 0.1798 | CGP-60474 | 1.11 | 31 | 0.1629 | BMS-387032 | 3.33 | ||||

| 17 | 0.1742 | BMS-387032 | 1.11 | 34 | 0.1573 | CGP-60474 | 1.11 | ||||

| 18 | 0.1742 | CGP-60474 | 0.37 | 37 | 0.1573 | A443654 | 3.33 | ||||

| 21 | 0.1685 | AZD-5438 | 10 | 44 | 0.1517 | WZ-3105 | 10 | ||||

| 22 | 0.1685 | BMS-387032 | 0.37 | 3 | MCF10A | 7 | 0.1966 | BMS-387032 | 3.33 | ||

| 23 | 0.1685 | BMS-387032 | 3.33 | 14 | 0.1798 | Alvocidib | 0.37 | ||||

| 24 | 0.1685 | AT-7519 | 1.11 | 19 | 0.1742 | CGP-60474 | 3.33 | ||||

| 30 | 0.1629 | Linifanib | 10 | 26 | 0.1685 | CGP-60474 | 0.37 | ||||

| 35 | 0.1573 | AZD-7762 | 3.33 | 38 | 0.1573 | CGP-60474 | 0.12 | ||||

| 36 | 0.1573 | Dasatinib | 3.33 | 39 | 0.1573 | CGP-60474 | 10 | ||||

| 45 | 0.1517 | AT-7519 | 3.33 | 46 | 0.1517 | AZD-5438 | 10 | ||||

| MDAMB231 | 15 | 0.1798 | Alvocidib | 0.12 | 6.0 | PC3 | 32 | 0.1573 | Daunorubicin hydrochloride | 10.0 | |

| 27 | 0.1685 | AT-7519 | 1.11 | 33 | 0.1573 | 16-HYDROXYTRIPTOLIDE | 0.08 | ||||

| 28 | 0.1685 | CGP-60474 | 0.12 | 43 | 0.1517 | Triptolide | 10.0 | ||||

| 40 | 0.1573 | BMS-387032 | 1.11 | 24.0 | HA1E | 20 | 0.1685 | Geldanamycin | 10.0 | ||

| 41 | 0.1573 | CGP-60474 | 3.33 | 6.0 | HCC515 | 50 | 0.1461 | ER 27319 maleate | 10.0 | ||

| 42 | 0.1573 | CGP-60474 | 1.11 | ||||||||

| 47 | 0.1517 | AT-7519 | 3.33 | ||||||||

| 48 | 0.1517 | CGP-60474 | 10 | ||||||||

| 49 | 0.1517 | Alvocidib | 3.33 |

Table 5.

Small molecule drug signature and combination.

| Rank | Score | Combination | Rank | Score | Combination | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.3371 | 1. CGP-60474 | 35. AZD-7762 | 26 | 0.2865 | 1. CGP-60474 | 33. 16-HYDROXYTRIPTOLIDE |

| 2 | 0.3258 | 1. CGP-60474 | 20. Geldanamycin | 27 | 0.2865 | 5. Alvocidib | 35. AZD-7762 |

| 3 | 0.3202 | 2. Alvocidib | 35. AZD-7762 | 28 | 0.2865 | 6. Alvocidib | 35. AZD-7762 |

| 4 | 0.3146 | 2. Alvocidib | 20. Geldanamycin | 29 | 0.2865 | 8. Alvocidib | 35. AZD-7762 |

| 5 | 0.3146 | 3. CGP-60474 | 20. Geldanamycin | 30 | 0.2865 | 26. CGP-60474 | 35. AZD-7762 |

| 6 | 0.3146 | 3. CGP-60474 | 35. AZD-7762 | 31 | 0.2865 | 2. Alvocidib | 36. Dasatinib |

| 7 | 0.3146 | 1. CGP-60474 | 36. Dasatinib | 32 | 0.2865 | 7. BMS-387032 | 36. Dasatinib |

| 8 | 0.309 | 7. BMS-387032 | 35. AZD-7762 | 33 | 0.2865 | 13. BMS-387032 | 36. Dasatinib |

| 9 | 0.309 | 13. BMS-387032 | 35. AZD-7762 | 34 | 0.2865 | 14. Alvocidib | 36. Dasatinib |

| 10 | 0.3034 | 14. Alvocidib | 35. AZD-7762 | 35 | 0.2865 | 35. AZD-7762 | 38. CGP-60474 |

| 11 | 0.2978 | 19. CGP-60474 | 35. AZD-7762 | 36 | 0.2809 | 1. CGP-60474 | 2. Alvocidib |

| 12 | 0.2978 | 25. Alvocidib | 35. AZD-7762 | 37 | 0.2809 | 2. Alvocidib | 3. CGP-60474 |

| 13 | 0.2978 | 28. CGP-60474 | 35. AZD-7762 | 38 | 0.2809 | 1. CGP-60474 | 10. CGP-60474 |

| 14 | 0.2978 | 29. PF-431396 | 35. AZD-7762 | 39 | 0.2809 | 5. Alvocidib | 20. Geldanamycin |

| 15 | 0.2921 | 4. A443654 | 20. Geldanamycin | 40 | 0.2809 | 7. BMS-387032 | 20. Geldanamycin |

| 16 | 0.2921 | 4. A443654 | 35. AZD-7762 | 41 | 0.2809 | 10. CGP-60474 | 20. Geldanamycin |

| 17 | 0.2921 | 10. CGP-60474 | 35. AZD-7762 | 42 | 0.2809 | 11. CGP-60474 | 20. Geldanamycin |

| 18 | 0.2921 | 15. Alvocidib | 35. AZD-7762 | 43 | 0.2809 | 12. CGP-60474 | 20. Geldanamycin |

| 19 | 0.2921 | 16. CGP-60474 | 35. AZD-7762 | 44 | 0.2809 | 20. Geldanamycin | 24. AT-7519 |

| 20 | 0.2921 | 27. AT-7519 | 35. AZD-7762 | 45 | 0.2809 | 9. PF-562271 | 35. AZD-7762 |

| 21 | 0.2921 | 31. BMS-387032 | 35. AZD-7762 | 46 | 0.2809 | 18. CGP-60474 | 35. AZD-7762 |

| 22 | 0.2921 | 3. CGP-60474 | 36. Dasatinib | 47 | 0.2809 | 32. Daunorubicin hydrochloride | 35. AZD-7762 |

| 23 | 0.2865 | 6. Alvocidib | 20. Geldanamycin | 48 | 0.2809 | 34. CGP-60474 | 35. AZD-7762 |

| 24 | 0.2865 | 8. Alvocidib | 20. Geldanamycin | 49 | 0.2809 | 8. Alvocidib | 36. Dasatinib |

| 25 | 0.2865 | 9. PF-562271 | 20. Geldanamycin | 50 | 0.2809 | 19. CGP-60474 | 36. Dasatinib |

Conclusions

Our study targets to provide detailed guidance for future fundamental researches along with some key genes, TFs and miRNAs, which are potential biomarkers for silicosis. The approach used in the manuscript allows us to incorporate various data sources into an integrated network, analysis of network parameters in order to find key network elements. Using various data sources, we found the relationships between different molecular components to support our comprehension of how silicosis progresses. In this study, 235 differentially expressed genes (150 down-expressed and 85 up-expressed) are identified as affected by exposure to crystalline silica. These genes are regulated by 24 TFs and 1100 very high target miRNAs. The network between DEGs, TFs and miRNAs are constructed using the various plug-in of Bioconductor, Cytoscape and MCODE to find the associateship of their various aspects. Total of 14 clusters of the network is achieved where only six clusters there is Gene-TFs-miRNA interaction and other eight clusters posess DEGs–miRNAs interactions or DEGs–DEGs–miRNAs interactions The most targeted genes and TFs as well as miRNAs are observed in cluster 3 to cluster 5 in the network analysis that may help in providing a detailed diagnosis of the disease for its cure. Maximum interacted DEGs with miRNA in terms of category are CDK19 (up-regulated) and ARID5B (down-regulated). Maximum interacted DEGs with DEGs and TFs are CEBPG, RELA, BACH1, FOXF1 and CHD1 wheras maximum interacted TFs are NR4A2, CDKN1A, ATF3, ERRFI1, FOSB and EGR1. Functional analysis of the DEGs given that the highest number (11) genes are responsible for Rab proteins signal transduction (Biological Process). Also, Cellular Senescence (20), IL-17 signaling pathway (16) and Signalling by Nuclear Receptors (14) is the dominant Biological Pathway among others. Maximum scoring small-molecule combinations are CGP-60774 (total 20 combinations) followed by alvocidib (total 15 combinations) and with AZD-7762 (total 24 combinations) is found with few other drugs having a high probability of success.

Supplementary information

Author contributions

J.K.C. analysed the bioinformatics part by using systems biology approach propagated network of gene/miRNA/transcription factor with interactions responsible for silicosis by integrating publicly available data. M.K.V. contributed substantially to the conception and design of the study. J.C. interpreted the finding the interaction and research. B.P.S. compiled the manuscript in the term of bioinformatics and environmental aspect.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-77636-4.

References

- 1.Barnes H, Goh NS, Leong TL, Hoy R. Silica-associated lung disease: an old-world exposure in modern industries. Respirology. 2019;24:1165–1175. doi: 10.1111/resp.13695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leso V, Fontana L, Romano R, Gervetti P, Iavicoli I. Artificial stone associated silicosis: a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16:568. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16040568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.León-Jiménez A, Hidalgo-Molina A, Conde-Sánchez MÁ, Pérez-Alonso A, Morales-Morales JM, García-Gámez EM, Córdoba-Doña JA. Artificial stone silicosis: rapid progression following exposure cessation. Chest. 2020;158:1060–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baur X, Sanyal S, Abraham JL. Mixed-dust pneumoconiosis: review of diagnostic and classification problems with presentation of a work-related case. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;652:413–421. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang D, et al. Comparison of risk of silicosis in metal mines and pottery factories: A 44-year cohort study. Chest. 2020;158(3):1050–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leung CC, Yu ITS, Chen W. Silicosis. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2012;379:2008–2018. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tian T, Shu Y, Chen J, Hu Z, Xu L, Jin G, Liang J, Liu P, Zhou X, Miao R. A functional genetic variant in microRNA-196a2 is associated with increased susceptibility of lung cancer in Chinese. Cancer Epidemiol. Prev. Biomark. 2009;18:1183–1187. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Napierska D, Thomassen LC, Lison D, Martens JA, Hoet PH. The nanosilica hazard: another variable entity. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2010;7:39. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-7-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rose C, Heinzerling A, Patel K, Sack C, Wolff J, Zell-Baran L, Weissman D, Hall E, Sooriash R, McCarthy RB. Severe Silicosis in engineered stone fabrication workers—California, Colorado, Texas, and Washington, 2017–2019. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019;68:813. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6838a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan JYW, Tsui JCC, Law PTW, So WKW, Leung DYP, Sham MMK, Tsui SKW, Chan CWH. Regulation of TLR4 in silica-induced inflammation: an underlying mechanism of silicosis. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2018;15:986. doi: 10.7150/ijms.24715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steenland K, Mannetje A, Boffetta P, Stayner L, Attfield M, Chen J, Dosemeci M, DeKlerk N, Hnizdo E, Koskela R. Pooled exposure–response analyses and risk assessment for lung cancer in 10 cohorts of silica-exposed workers: an IARC multicentre study. Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:773–784. doi: 10.1023/A:1012214102061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Souza TP, Watte G, Gusso AM, Souza R, Moreira JDS, Knorst MM. Silicosis prevalence and risk factors in semi-precious stone mining in Brazil. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2017;60:529–536. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pandey JK, Agarwal D. Biomarkers: a potential prognostic tool for silicosis. Indian J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2012;16:101. doi: 10.4103/0019-5278.111746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bandyopadhyay A, Majumdar K, Chakraborty A, Mitra P, Nag S. CT-guided aspiration cytology of advanced silicosis and confirmation of the deposited zeolite nano particles through X ray diffraction: a novel approach. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2016;44:246–249. doi: 10.1002/dc.23415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao X, et al. Pulmonary silicosis alters microRNA expression in rat lung and miR-411-3p exerts anti-fibrotic effects by inhibiting MRTF-A/SRF signaling. Mol. Ther.-Nucleic Acids. 2020;20(5):851–865. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2020.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sellamuthu R, Umbright C, Li S, Kashon M, Joseph P. Mechanisms of crystalline silica-induced pulmonary toxicity revealed by global gene expression profiling. Inhal. Toxicol. 2011;23:927–937. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2011.625995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang X, Jia X, Mei L, Zheng M, Yu C, Ye M. Global DNA methylation and PTEN hypermethylation alterations in lung tissues from human silicosis. J. Thorac. Dis. 2016;8:2185. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2016.07.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fielden MR, Brennan R, Gollub J. A gene expression biomarker provides early prediction and mechanistic assessment of hepatic tumor induction by nongenotoxic chemicals. Toxicol. Sci. 2007;99:90–100. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang W, Liu H, Dai X, Fang S, Wang X, Zhang Y, Yao H, Zhang X, Chao J. p53/PUMA expression in human pulmonary fibroblasts mediates cell activation and migration in silicosis. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:16900. doi: 10.1038/srep16900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kauffmann A, Gentleman R, Huber W. ArrayQualityMetrics—a bioconductor package for quality assessment of microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:415–416. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D’Souza M, Zhu X, Frisina RD. Novel approach to select genes from RMA normalized microarray data using functional hearing tests in aging mice. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2008;171:279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diboun I, Wernisch L, Orengo CA, Koltzenburg M. Microarray analysis after RNA amplification can detect pronounced differences in gene expression using limma. BMC Genom. 2006;7:252. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bader GD, Hogue CW. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinform. 2003;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benjamini Y, Drai D, Elmer G, Kafkafi N, Golani I. Controlling the false discovery rate in behavior genetics research. Behav. Brain Res. 2001;125:279–284. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(01)00297-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verfaillie A, Imrichová H, Van de Sande B, Standaert L, Christiaens V, Hulselmans G, Herten K, Sanchez MN, Potier D, Svetlichnyy D. iRegulon: from a gene list to a gene regulatory network using large motif and track collections. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014;10:e1003731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tokar T, Pastrello C, Rossos AEM, Abovsky M, Hauschild A-C, Tsay M, Lu R, Jurisica I. mirDIP 41-integrative database of human microRNA target predictions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D360–D370. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Hackl H, Charoentong P, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, Fridman W-H, Pagès F, Trajanoski Z, Galon J. ClueGO: a Cytoscape plug-in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1091–1093. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bindea G, Galon J, Mlecnik B. CluePedia Cytoscape plugin: pathway insights using integrated experimental and in silico data. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:661–663. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duan Q, Reid SP, Clark NR, Wang Z, Fernandez NF, Rouillard AD, Readhead B, Tritsch SR, Hodos R, Hafner M. L1000CDS 2: LINCS L1000 characteristic direction signatures search engine. NPJ Syst. Biol. Appl. 2016;2:1–12. doi: 10.1038/npjsba.2016.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kutmon M, Ehrhart F, Willighagen EL, Evelo CT, Coort SL. CyTargetLinker app update: a flexible solution for network extension in Cytoscape. F100Research. 2019;7:743. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.14613.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun J, Li Q, Lian X, Zhu Z, Chen X, Pei W, Li S, Abbas A, Wang Y, Tian L. MicroRNA-29b mediates lung mesenchymal-epithelial transition and prevents lung fibrosis in the silicosis model. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2019;14:20–31. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2018.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu Q, Han L, Yan W, Ji X, Han R, Yang J, Yuan J, Ni C. miR-489 inhibits silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis by targeting MyD88 and Smad3 and is negatively regulated by lncRNA CHRF. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:30921. doi: 10.1038/srep30921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y, Li C, Lu Y, Zhuang H, Gu W, Liu B, Liu F, Sun J, Yan B, Weng D. IL-10-producing CD1dhiCD5+ regulatory B cells may play a critical role in modulating immune homeostasis in silicosis patients. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:110. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Z, Li Q, Yao S, Zhang G, Xue R, Li G, Wang Y, Wang S, Wu R, Gao H. Down-regulation of miR-19a as a biomarker for early detection of silicosis. Anat. Rec. 2016;299:1300–1307. doi: 10.1002/ar.23381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faxuan W, Qin Z, Dinglun Z, Tao Z, Xiaohui R, Liqiang Z, Yajia L. Altered microRNAs expression profiling in experimental silicosis rats. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2012;37:1207–1215. doi: 10.2131/jts.37.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, Wang F, Zhou D, Ren X, Zhou D, Gao X, Lan Y, Zhang Q, Xie X. Genome-wide analysis of aberrantly expressed microRNAs in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with silicosis. Ind. Health. 2016;54:361–369. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.2015-0170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou J, Li J, Serafim RB, Ketchum S, Ferreira CG, Liu JC, Coe KA, Price BD, Yusufzai T. Human CHD1 is required for early DNA-damage signaling and is uniquely regulated by its N terminus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:3891–3905. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suragani RN, Zachariah RS, Velazquez JG, Liu S, Sun C-W, Townes TM, Chen J-J. Heme-regulated eIF2α kinase activated Atf4 signaling pathway in oxidative stress and erythropoiesis. Blood. 2012;119:5276–5284. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-388132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.D’Anna NM, Crawford EL, Harr MW, Willey JC. CEBPG transcription factor correlation with antioxidant and DNA repair genes in normal bronchial epithelial cells of individuals with and without bronchogenic carcinoma. AACR. 2006;66:32–33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-5-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Guo YR, Liu K, Yin Z, Liu R, Xia Y, Tan L, Yang P, Lee J-H, Li X. KAT2A coupled with the α-KGDH complex acts as a histone H3 succinyltransferase. Nature. 2017;552:273–277. doi: 10.1038/nature25003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chaudhari N, Talwar P, Parimisetty A, Lefebvre d’Hellencourt C, Ravanan P. A molecular web: endoplasmic reticulum stress, inflammation, and oxidative stress. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2014;8:213. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kang H, Kim YS, Ko J. A novel isoform of human LZIP negatively regulates the transactivation of the glucocorticoid receptor. Mol. Endocrinol. 2009;23:1746–1757. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Messina G, Cossu G. The origin of embryonic and fetal myoblasts: a role of Pax3 and Pax7. Genes Dev. 2009;23:902–905. doi: 10.1101/gad.1797009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buckingham, M. & Relaix, F.: PAX3 and PAX7 as upstream regulators of myogenesis. In Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. pp. 115–125 (Elsevier, 2015) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Drozniewska M, Haus O. PAX3 gene deletion detected by microarray analysis in a girl with hearing loss. Mol. Cytogenet. 2014;7:30. doi: 10.1186/1755-8166-7-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kalinichenko VV, Gusarova GA, Kim I-M, Shin B, Yoder HM, Clark J, Sapozhnikov AM, Whitsett JA, Costa RH. Foxf1 haploinsufficiency reduces Notch-2 signaling during mouse lung development. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2004;286:L521–L530. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00212.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ustiyan V, Bolte C, Zhang Y, Han L, Xu Y, Yutzey KE, Zorn AM, Kalin TV, Shannon JM, Kalinichenko VV. FOXF1 transcription factor promotes lung morphogenesis by inducing cellular proliferation in fetal lung mesenchyme. Dev. Biol. 2018;443:50–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.A subcellular map of the human proteome | Science, https://science.sciencemag.org/content/356/6340/eaal3321. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Shu W, Lu MM, Zhang Y, Tucker PW, Zhou D, Morrisey EE. Foxp2 and Foxp1 cooperatively regulate lung and esophagus development. Development. 2007;134:1991–2000. doi: 10.1242/dev.02846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.The p38 MAPK–MK2 Axis Regulates E2F1 and FOXM1 Expression after Epirubicin Treatment | Molecular Cancer Research, https://mcr.aacrjournals.org/content/10/9/1189.short. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Salon C, Eymin B, Micheau O, Chaperot L, Plumas J, Brambilla C, Brambilla E, Gazzeri S. E2F1 induces apoptosis and sensitizes human lung adenocarcinoma cells to death-receptor-mediated apoptosis through specific downregulation of c-FLIP short. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:260–272. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coe BP, Thu KL, Aviel-Ronen S, Vucic EA, Gazdar AF, Lam S, Tsao M-S, Lam WL. Genomic deregulation of the E2F/Rb pathway leads to activation of the oncogene EZH2 in small cell lung cancer. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e71670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu T, Zhang L, Joo D, Sun S-C. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017;2:1–9. doi: 10.1038/sigtrans.2017.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mullany LE, Herrick JS, Wolff RK, Stevens JR, Samowitz W, Slattery ML. MicroRNA-transcription factor interactions and their combined effect on target gene expression in colon cancer cases. Genes. Chromosomes Cancer. 2018;57:192–202. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao, Q., Liu, H., Yao, C., Shuai, J. & Sun, X. Effect of Dynamic Interaction between microRNA and Transcription Factor on Gene Expression. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2016/2676282/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Gopal Krishnan PD, Golden E, Woodward EA, Pavlos NJ, Blancafort P. (2020) Rab GTPases: emerging oncogenes and tumor suppressive regulators for the editing of survival pathways in cancer. Cancers. 2020 doi: 10.3390/cancers12020259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tzeng H-T, Wang Y-C. Rab-mediated vesicle trafficking in cancer. J. Biomed. Sci. 2016;23:70. doi: 10.1186/s12929-016-0287-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.