Abstract

Fungal infections and toxicoses caused by insecticides may alter microbial communities and immune responses in the insect gut. We investigated the effects of Metarhizium robertsii fungus and avermectins on the midgut physiology of Colorado potato beetle larvae. We analyzed changes in the bacterial community, immunity- and stress-related gene expression, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and detoxification enzyme activity in response to topical infection with the M. robertsii fungus, oral administration of avermectins, and a combination of the two treatments. Avermectin treatment led to a reduction in microbiota diversity and an enhancement in the abundance of enterobacteria, and these changes were followed by the downregulation of Stat and Hsp90, upregulation of transcription factors for the Toll and IMD pathways and activation of detoxification enzymes. Fungal infection also led to a decrease in microbiota diversity, although the changes in community structure were not significant, except for the enhancement of Serratia. Fungal infection decreased the production of ROS but did not affect the gene expression of the immune pathways. In the combined treatment, fungal infection inhibited the activation of detoxification enzymes and prevented the downregulation of the JAK-STAT pathway caused by avermectins. The results of this study suggest that fungal infection modulates physiological responses to avermectins and that fungal infection may increase avermectin toxicosis by blocking detoxification enzymes in the gut.

Subject terms: Psychology, Microbial communities, Pathogens, Microbiology, Fungi, Fungal host response

Introduction

Insect microbial associates play important roles in the development of diseases caused by entomopathogens1 and toxicoses caused by insecticides2. Different types of interactions may be observed between bacterial symbionts and insect pathogenic ascomycetes (e.g., Beauveria and Metarhizium), which infect their hosts primarily through integuments and, less frequently, through the gut. These fungi may interact with host bacteria directly on the cuticle surface or in the gut. In these cases, bacteria inhibit fungal growth and differentiation, thereby acting as a component of the defense system against fungal infections3–6. In contrast, indirect interactions between fungi and symbiotic bacteria may be mediated by host immune responses. These more complicated interactions include the spatial relocation of physiological reactions, which may lead to synergy between the microorganisms and accelerated mortality. For example, topical infection of the mosquito Anopheles with the fungus Beauveria bassiana led to the proliferation of bacteria Serratia marcescens in the gut and hemocoel, thereby promoting fungal infection7. Similar effects were observed for the bark beetle Dendroctonus valens8 and the wax moth Galleria mellonella9.

In natural and agricultural habitats, insects are exposed to a broad range of entomopathogenic microorganisms and various toxicants, such as plant secondary metabolites, synthetic and natural insecticides, and parasitoid venoms. It is well-known that these toxicants may significantly modulate the susceptibility of hosts to fungal pathogens10,11. Various approaches for integrated pest control have been developed on this basis12–18. Researchers usually explain synergy between pathogenic fungi and insecticides by altering the immune response to fungal infections, as well as developmental and behavioral disorders. Importantly, xenobiotics may lead to changes in microbial communities in different ways. For example, certain insecticides cause different dysfunctions in the gut, such as alterations in peristaltic intensity, pH, and gut tissue damage19. Moreover, different toxicants may affect the immune and stress reactions in the gut. These effects may lead to changes in the bacterial community and, consequently, to changes in the susceptibility to fungi9,20.

Homeostasis in the gut bacterial community is determined by immune-physiological reactions, with many of these reactions producing reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antimicrobial peptides (AMPs)11,21. The level of ROS is dictated by the Mesh-DUOX system22. It was proposed that DUOX generates superoxides outside the cells, which are unstable and are rapidly converted to H2O223. In addition, the DUOX peroxidase homology domain may serve to convert H2O2 to HOCl24. All of these compounds are powerful oxidants and exhibit microbicidal activity24. It was shown for Drosophila and mosquito species that the Mesh-DUOX system is essential for both resistance to pathogens and the management of commensal microbial populations22,24–26. The inhibition of the Mesh-DUOX system leads to uncontrolled proliferation of bacteria in the gut and a reduction in insect survival7,22. Interestingly, downregulation of DUOX in the mosquito gut was observed after topical infection with the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana, as shown by Wei et al.7. However, contradictory results were obtained by Ramirez et al.27. AMP production is controlled by three major immune-signaling pathways: Toll, IMD and JAK-STAT. The Toll pathway is involved in the defense against gram-positive bacteria and fungi, the IMD pathway is primarily involved in the defense against gram-negative bacteria, and the JAK-STAT pathway is involved in the defense against viruses but also against fungi28 and bacteria26,29. Changes in the expression levels of the transcription factors Dif/Dorsal, Relish and Stat (or their orthologs) indicate the activation/inhibition of the Toll, IMD and JAK-STAT pathways, respectively27. Topical fungal infection may both downregulate and upregulate the expression of these transcription factors and AMPs in the gut, depending on certain models of pathogenesis7,9,27.

In insects, stress responses may play important roles in the response to fungi, bacteria and insecticides. In particular, heat-shock proteins are activated under various stress conditions, including infections and toxicoses30,31. These proteins participate in the stabilization and transport of proteins and are therefore involved in cell repair, immune-signaling pathways and other vital processes31,32. Antioxidants and detoxification enzymes participate in the inactivation of insecticides and microbial metabolites in various organs and tissues of insects, including the gut33. Esterases (ESTs) function against a broad range of insecticides34, bacterial toxins33,35 and metabolites formed under mycoses36. Glutathione-S-transferases (GSTs) participate in ROS inactivation and are involved in the metabolism of insecticides from different classes34 and are likely involved in the metabolism of fungal toxins37. The abovementioned immune responses in the insect gut during the development of mycoses or toxicoses caused by insecticides have not been fully elucidated, particularly when the fungi and insecticides are combined.

The Colorado potato beetle Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say) is an important pest in most potato-producing regions around the world. The rapid development of resistance to various chemical insecticides requires the development of integrated approaches to the control of L. decemlineata populations38. One of these approaches may be employing a combination of insecticides and entomopathogens13,17,39,40. Previously, we studied the immunophysiological mechanisms of the synergy between the fungus Metarhizium robertsii and the macrocyclic lactones avermectins after a combined treatment to control the Colorado potato beetle39,40. We have shown that avermectins cause a delay in larval development and inhibit cellular immunity, which disrupts the immune response against fungal infection. In this study, we attempted to determine how these agents influence the gut microbiota and gut immunity and whether these changes contribute to the synergy between the fungus and avermectins. We measured the changes in the microbiota structure, ROS production, detoxification system activity, and gene expression involved in the immune response and stress management in the Colorado potato beetle midgut under the oral administration of avermectins, topical infection with M. robertsii and combined treatment with these agents.

Results

Bioassay

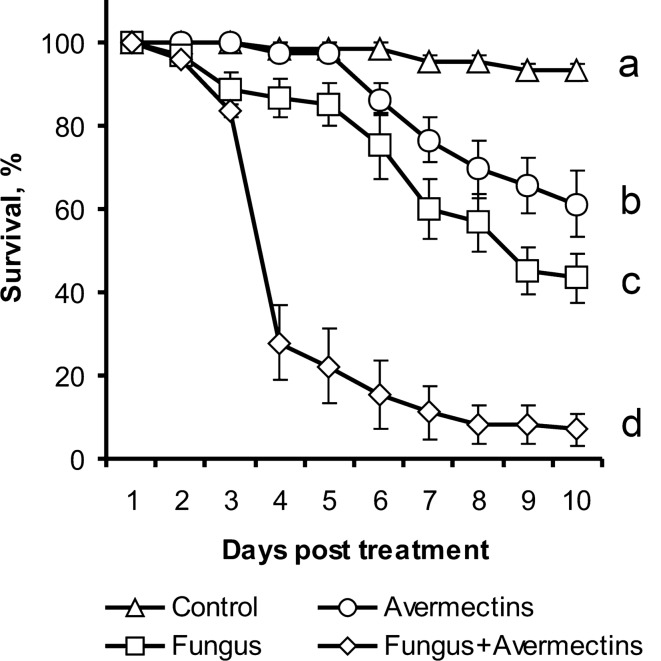

Treatment of Colorado potato beetle larvae with M. robertsii, avermectins and a combination of the two led to significant differences in the survival dynamics (log rank test: χ2 > 8.4, df = 1, P < 0.005, Fig. 1). Strong synergy between avermectin toxicosis and fungal infection in larval mortality was demonstrated from 4 to 10 days after treatment (χ2 > 10.2, df = 1, P < 0.001). At 10 days after treatment, the control larvae survived at a rate of 93.3%, whereas oral administration of avermectin and topical infection with fungus resulted in 61.1% and 43.3% survival, respectively, and the combined treatment resulted in 6.9% survival. Larvae that died after treatment with the fungus alone were primarily mummified (86%). Larvae that died after the combined treatment were mummified (39%) or decomposed by bacteria (61%), which was manifested by decay of cadavers with the appearance of an ammonia smell.

Figure 1.

Survival of Colorado potato beetle larvae after topical treatment with M. robertsii conidia, oral administration of avermectins and the combined treatment. Different letters indicate significant differences in survival dynamics (log rank test, χ2 > 8.4, df = 1, P < 0.005). Synergy was observed from 4 to 10 days (χ2 > 10.2 df = 1, P < 0.001).

Bacterial communities

An analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequencing in the whole experiment demonstrated the presence of 171 operative taxonomical units (OTUs) that belonged to bacteria from 63 families, 21 classes and 11 phyla (see Appendix 1). The predominant groups were enterobacteria (Proteobacteria, Enterobacteriaceae) and spiroplasmas (Tenericutes, Spiroplasmataceae). Blast analysis with GenBank-type material showed that the most abundant OTU, OTU-1, had 99.5–100% similarity with various species of Enterobacter and Klebsiella. The second most predominant OTU, OTU-20, showed high similarity (99.8%) only with Citrobacter strains. Spiroplasma (OTU-3) was identical (100%) only with Spiroplasma leptinotarsae (strain LD-1B), which is an obligate symbiont of the Colorado potato beetle41. In addition, relatively high abundances of OTUs were identified as Serratia (Enterobacteriaceae), Acinetobacter (Moraxellaceae), Pseudomonas (Pseudomonadaceae) and Lactococcus (Streptococcaceae).

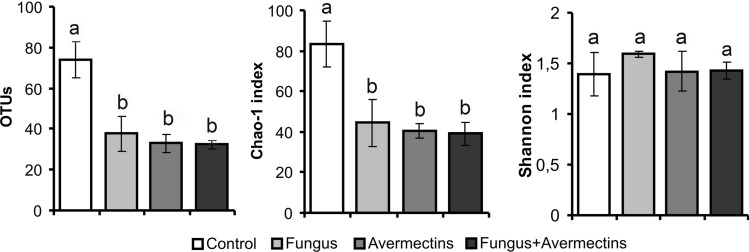

Fungal infection and avermectin toxicosis led to a reduction in the diversity of the midgut bacterial community (Fig. 2). In particular, we registered a 2- to 2.4-fold decrease in the total OTU counts (effect of fungus—F1,12 = 10.4, P = 0.007; effect of avermectins—F1,12 = 16.5, P = 0.002), as well as a 1.9- to 2.2-fold decrease in the Chao-1 index (effect of fungus—F1,12 = 7.3, P = 0.02; effect of avermectins—F1,12 = 10.4, P = 0.007). Notably, the combined treatment did not lead to a stronger decrease in diversity compared to the single treatments (Tukey’s test, P > 0.89). Based on changes in the Shannon index, significant effects were not detected (F1,12 < 1.3, P > 0.28).

Figure 2.

Diversity indexes of midgut bacterial communities of Colorado potato beetle larvae at 48 h after topical treatment with M. robertsii conidia, oral administration of avermectins and the combined treatment. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (Tukey’s test, P < 0.05).

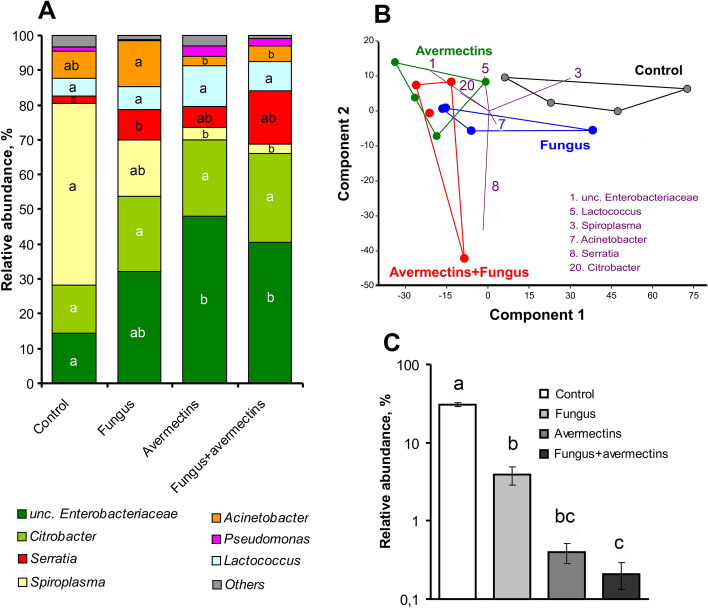

An analysis of the predominant taxa abundance showed that the effects of fungal infection were not significant, although trends of decreased abundance of Spiroplasma and increased abundance of unclassified Enterobacteriaceae and Serratia were observed (effect of fungus: H1.15 < 3.4, P > 0.059, Fig. 3A). However, fungal infection alone led to a significant increase in Serratia abundance compared to the control (Dunn’s test, P = 0.02). Avermectins caused a strong elevation of unclassified Enterobacteriaceae and decrease in Spiroplasma relative abundance (effect of avermectins: H1,15 > 5.3, P < 0.02). In addition, an increasing trend for Pseudomonas was observed after treatment with avermectins (H1,15 = 2.8, P = 0.09). Factor interactions (fungus × avermectins) in the changes of the predominant group of bacteria were not observed (H1,15 < 1.9, P > 0.17). The structure of bacterial communities was similar in the larvae treated with avermectins and the combination of avermectins and fungus. It is important to note that fungal infection and avermectin toxicosis led to a decrease in the relative abundance of chloroplast DNA by 10- and 100-fold, respectively (H1,15 > 11.0, P < 0.001, Fig. 3C), which indicates a disruption in the nutrition of treated insects.

Figure 3.

Alterations in bacterial communities in the midgut of Colorado potato beetle larvae at 48 h after topical treatment with M. robertsii conidia, oral administration of avermectins and the combined treatment. (A) Microbiota structure at the genus level, (B) PCA at the OTU level, with numbers indicating the predominant OTUs. (C) Changes in chloroplast 16S DNA relative abundance. Different letters indicate significant differences in taxa abundance between treatments (Dunn’s test, P < 0.05).

A principal component analysis showed clear clustering between communities of control insects and avermectin-treated insects (Fig. 3B). The community of insects treated with fungus alone occupied an intermediate location. The first component explained 66.0% of the variation, which was primarily due to changes in Spiroplasma and Enterobacteriaceae abundance. The second component explained 13.0% of the variation caused by an increase in Serratia abundance under the condition of fungal infection.

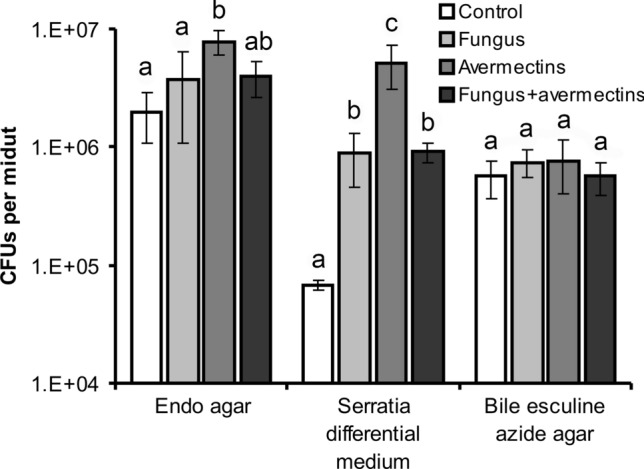

Changes in colony-forming unit (CFU) count

An analysis of CFU count on endo-agar medium indicated a significant interaction between M. robertsii infection and avermectin toxicosis (H1,39 = 4.2, P = 0.04, Fig. 4). This interaction can be explained by a significant fourfold enhancement of enterobacteria CFUs in the midgut after treatment with avermectins (Dunn’s test, P = 0.002 compared to the control) but only a twofold insignificant increase of the CFUs after the fungal and combined treatments (P > 0.12 compared to the control). Thus, fungal infection inhibited the proliferation of enterobacteria under the development of avermectin toxicosis. The same pattern was demonstrated for the CFUs on the Serratia differential medium. The factor interaction between infection and toxicosis was also significant (H1,39 = 8.5, P = 0.003, Fig. 4) due to a stronger elevation of the CFU count under avermectin toxicosis, although this effect was less pronounced under fungal infection and the combined treatment with fungus and avermectins. The count of CFUs on bile esculin azide agar (a medium employed for the differentiation of Firmicutes) did not exhibit any significant effects or differences between treatments.

Figure 4.

CFU count in the midgut of Colorado potato beetle larvae at 48 h after topical treatment with M. robertsii conidia, oral administration of avermectins and the combined treatment. Selective media for Enterobacteriaceae (Endo agar), Serratia (Serratia differential medium), Enterococcus and Lactococcus (bile esculin azide agar) were used. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (Dunn’s test, P < 0.05).

Expression of immunity-, stress- and ROS-related genes

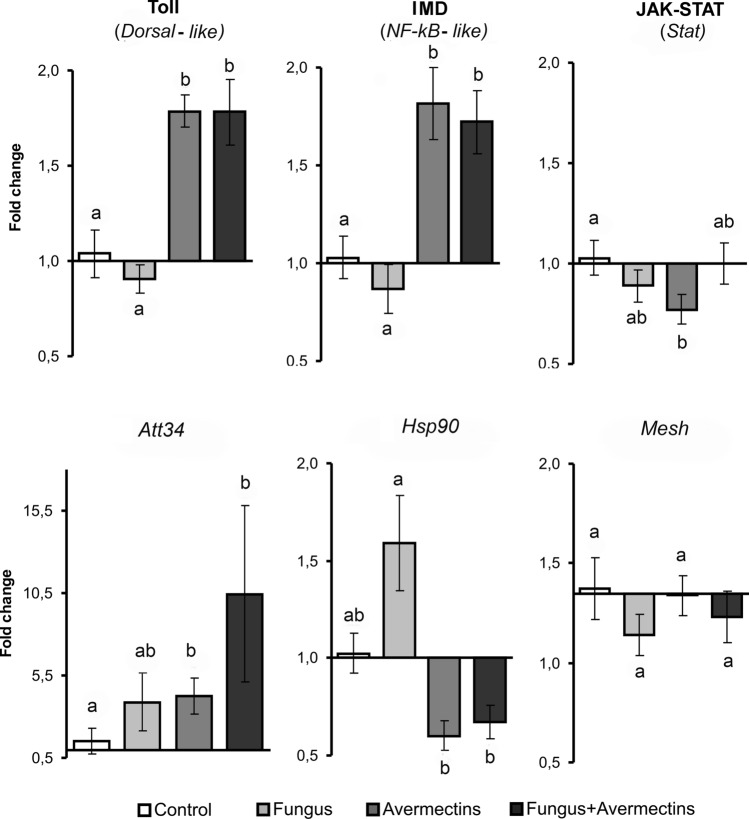

We determined the upregulation of the transcription factors Dorsal-like and NF-kB-like of the Toll and IMD pathways in the midguts under the influence of avermectin toxicosis (H1,23 > 14.3, P < 0.0005, Fig. 5). The treatment with avermectins alone and the combination treatment (avermectins + fungus) led to 1.7- to 1.8-fold increases in the expression of these genes, respectively (Dunn’s test, P < 0.02 compared to the control). Fungal infection alone caused an insignificant 1.2-fold downregulation of Dorsal-like and NF-kB-like expression (P > 0.58 compared to the control). The transcription factor Stat of the JAK-STAT pathway exhibited a different pattern of expression. Stat was significantly downregulated after treatment with avermectins alone (Dunn’s test, P = 0.02 compared to the control). However, the combined treatment and fungal infection alone did not result in changes in Stat expression compared with the control. The fungus × avermectins interaction was determined to be significant (H1,23 = 5.5, P = 0.02). Thus, fungal infection prevented the downregulation of Stat caused by avermectins.

Figure 5.

Alterations in the expression of transcriptional factors of Toll, IMD and JAK-STAT immune-signaling pathways, antimicrobial peptide attacin 34 (Att34), heat-shock protein (Hsp90) and DUOX regulator (Mesh) in the midgut of Colorado potato beetle larvae at 48 h after topical treatment with M. robertsii conidia, oral administration of avermectins and the combined treatment. Data were normalized based on the expression of two reference genes, Rp4 and Arf19. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (Dunn’s test, P < 0.05).

The expression of the AMP Attacin 34 (Att34) significantly increased after treatment with avermectins (H1,23 = 6.3, P = 0.01) and insignificantly increased with fungal infection (H1,23 = 3.1, P = 0.08, Fig. 5). Interestingly, single treatments upregulated Att34 by 2.6–2.7-fold (Dunn’s test, P = 0.07 and P = 0.05 for mycosis and avermectin toxicosis, respectively), whereas the combined treatment upregulated this gene by sevenfold (P = 0.02 compared to the control). Hsp90 was significantly downregulated under the influence of avermectins (H1,23 = 12.2, P = 0.0005) and was insignificantly upregulated after treatment with the fungus alone (P = 0.16 compared to the control); however, a significant effect of the interaction between factors on Hsp90 expression was not observed (H1,23 = 0.5, P = 0.5). Expression of Mesh did not exhibit any significant effects, although a trend of decreased expression was observed under the influence of mycosis (H1,23 = 2.3, P = 0.13).

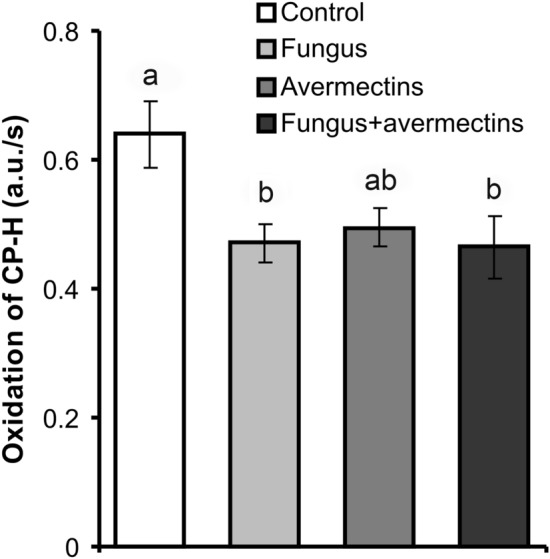

ROS production

Analysis of ROS production using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy demonstrated that M. robertsii infection significantly reduced the rate of ROS generation in Colorado potato beetle midguts (effect of fungus: F1,34 = 5.6, P = 0.02, Fig. 6). In both the fungal and combined treatments, ROS production decreased by 1.4-fold (Tukey’s test, P < 0.037 compared to the control). After treatment with avermectins, ROS production was also decreased, but the effect was not significant (F1,34 = 2.7, P = 0.08). The combined treatment did not lead to additional suppression of ROS production compared to individual treatments (Tukey’s test, P > 0.96). Positive correlations between the level of ROS production and diversity of the gut microbiota, especially based on the OTU count and Chao-1 index, were demonstrated (r = 0.98, n = 4, P = 0.03 and r = 0.98, n = 4, P = 0.02, respectively). Moreover, the level of ROS production was positively correlated with Mesh expression (r = 0.80, n = 4), although the correlation was not significant (P = 0.20).

Figure 6.

ROS production in the midgut tissue of Colorado potato beetle larvae at 48 h after topical treatment with M. robertsii conidia, oral administration of avermectins and the combined treatment. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (Tukey's test, P < 0.05).

Detoxification enzymes

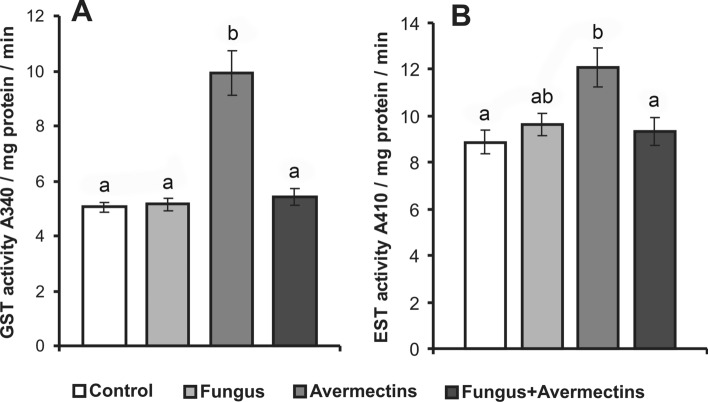

We demonstrated significant factor interactions in the activities of GST and EST in the Colorado potato beetle midgut after treatment with fungus and avermectins (GST—F1,71 = 26.4, P < 0.001, EST—F1,70 = 7.4, P = 0.001, Fig. 7). Avermectin treatment alone led to a twofold increase in the GST level compared with the control (Tukey’s test, P < 0.0005); however, GST activity did not change after fungal infection alone or combined treatment with fungus and avermectins (P > 0.92 compared to the control). A similar pattern was demonstrated for EST activity. Avermectins caused a 1.4-fold enhancement in EST activity (P = 0.006, compared to the control), although such a change was not observed after fungal infection alone or the combined treatment (P > 0.95, compared to the control). Thus, fungal infection inhibited the upregulation of detoxification enzymes caused by avermectins.

Figure 7.

Changes in GST (A) and EST (B) activity in the midgut of Colorado potato beetle larvae at 48 h after topical treatment with M. robertsii conidia, oral administration of avermectins and the combined treatment. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (Tukey's test, P < 0.05).

Combined effect of Serratia isolates and M. robertsii on larvae mortality

Since we observed an increase in the proliferation of the opportunistic pathogen Serratia under both mycosis and avermectin toxicosis (Fig. 4), we identified Serratia isolates and analyzed the larvae mortality dynamics after orally administering these bacteria and topical infection with M. robertsii. An analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequencing identified isolates belonging to S. marcescens, S. nematodiphila and S. quinivorans (Appendix 2, Table S1). Weak effects on the mortality dynamics were observed between M. robertsii and Serratia isolates (Appendix 2, Fig. S1). In particular, S. marcescens demonstrated slow synergy (12%) only on day 5 after treatment (χ2 = 9.2, df = 1, P < 0.01). An analogous weak effect was detected between M. robertsii and S. nematodiphila. No synergy was observed between M. robertsii and S. quinivorans. The total mortality at day 10 after treatment for all combinations and fungal infections alone was 76–81%. It should be noted that individual administration of S. liquefaciens and S. nematodiphila led to a 19–23% increase in mortality compared to the control, and the differences were significant (log rank test: χ2 > 10.72, df = 1, P < 0.001). Individual administration of S. marcescens did not cause mortality of larvae (χ2 = 1.31, df = 1, P > 0.05, compared to the control).

Discussion

This work demonstrated dramatic changes in the Colorado potato beetle midgut bacterial community after treatment with avermectins, as indicated by a reduction in diversity, proliferation of enterobacteria, and decrease in the relative abundance of Spiroplasma. Fungal infection also led to a decrease in the midgut microbiota diversity; however, changes in the community structure were less pronounced and were largely insignificant. Importantly, under the combined treatment (M. robertsii + avermectins), fungal infection inhibited enterobacterial proliferation and impeded the activation of the detoxification system in the midgut caused by avermectins. Thus, fungal infection may modulate the physiological response of insects to toxicosis caused by the insecticide in the midgut.

Overall, the structure of the Colorado potato beetle gut microbiota was consistent with earlier published data3,42–45, including data for the West Siberian population of the beetle, where Enterobacteriaceae and Spiroplasma predominated46. In the present study, a decrease in bacterial diversity under both avermectin toxicosis and mycosis clearly had two causes: (1) interruption of feeding, which is evidenced by the decreased abundance of chloroplast 16S DNA, and (2) elevation of enterobacteria abundance. The first finding is consistent with our previous work40, where we showed that the same concentrations of avermectins reduced the amount of food consumed threefold during the first day after treatment. Moreover, a trend toward a decrease in larval weight was observed after infection with the fungus M. robertsii40, which may also indicate interruption of feeding. An increase in Proteobacteria (including Enterobacteriaceae) proliferation under different pathological states has also been reported by other authors8,9,47,48 and may be explained by degenerative changes in the gut tissue, pH alterations, peristaltic disturbances and aeration changes. Enterobacteria are facultative anaerobes; therefore, a deceleration of peristalsis may increase their abundance. A shift in the bacterial community structure toward enterobacteria predomination was demonstrated in the wax moth gut after treatment with H. hebetor venom, which leads to a cessation of peristalsis9. A decrease in the relative abundance of obligate intracellular S. leptinotarsa may be explained by the elevation of enterobacteria, as well as by the destruction of midgut epithelial cells after treatment with avermectins. Damage to the gut tissue by avermectins was demonstrated for different insects, especially for mosquitoes19 and Colorado potato beetles (Kryukova, O. Polenogova, unpublished).

In a previous work46, we observed slight changes in the structure of the bacterial community and total bacterial load during the development of prolonged mycoses caused by different strains of M. robertsii, which is consistent with the results of the present study. However, in the present work, we documented an increase in the relative abundance and CFU count of Serratia during fungal infection, as well as during avermectin toxicosis. Previous studies showed that the oral administration of enterobacteria (Serratia, Erwinia, and Enterobacter) that proliferate in the gut under mycoses and other pathologies caused different insect taxa to be more susceptible to fungi7–9. In this study, oral administration of different Serratia cultures to Colorado potato beetle larvae had a weak effect on mycosis development (Fig. S1), although some Serratia cultures demonstrated a degree of virulence.

With fungal infection, we observed a trend of decreasing Mesh expression, which regulates the activity of the DUOX system. Moreover, fungal infection alone or in combination with avermectins led to a significant decrease in ROS production in the midgut. An elevation of bacterial load, especially Serratia, was likely caused by a reduction in ROS generation. This effect has been reported by Wei et al. regarding studies on Anopheles7. The authors suggested that a decrease in ROS production in the gut after topical treatment with B. bassiana was caused by fungal toxins, and the effect of oosporeins on the DUOX system was highlighted7. Metarhizium fungi produce the major metabolite destruxins that disrupt the circulation of Ca2+ and K+ ions in cells of different organs, including the gut, as shown in ex vivo tests49. However, at the initial stages of Metarhizium infection (48 h after treatment), destruxins were detected in negligible concentrations in insects50. The decrease in ROS production in the midgut was likely caused by prioritization of the immune response between the integuments and midgut. Insignificant effects of fungal infection on gene expression in the IMD and Toll and JAK-STAT pathways in Colorado potato beetle midgut may have been caused by the initial stage of mycosis, when the main action of fungal metabolites is the hydrolysis of integuments. Alterations in the expression of the genes in the gut were primarily identified at the latter stages of mycoses, as shown for mosquitoes27.

Avermectin toxicosis did not lead to changes in Mesh expression, and decreased ROS generation was only observed as a trend (P = 0.08). However, avermectin treatment led to a stronger perturbation of the bacterial community and the strongest increase in the bacterial load compared to fungal infection. Clearly, these changes were caused by pathological processes directly in the gut. Upregulation of transcriptional factors in the Toll and IMD pathways and the AMP attacin after avermectin treatment may be considered to be a response to the elevated bacterial load. Interestingly, avermectin treatment caused a weak reaction or inhibition of stress- and ROS-related systems in the gut. This insecticide affects the glutamate-gated chloride channel (GluCl) and is associated with the ɣ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor, and it also disrupts intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis51,52, which leads to the failure of the ion-exchange function of cellular membranes, disruption of the receptors containing G-protein (GPCRs)53, and inactivation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPК)54. It is possible that these processes block or downregulate the expression of stress- and ROS-related genes (Mesh and Hsp90), as well as the JAK-STAT immune-signaling pathway. However, the IMD and Toll pathways are activated through the PGRP or TLR (Toll-like receptor) and PGRP receptors55, and they continue to function. Therefore, we observed the upregulation of the Dorsal-like and NF-kB-like genes. Activation of the IMD and Toll pathways is likely to be less dependent on Ca2+ homeostasis.

It should be noted that similar patterns in gene expression in insect midguts were observed after treatment with other toxicants. In particular, envenomation of the wax moth Galleria mellonella by the parasitoid H. hebetor led to the downregulation of stress- and ROS-related genes, which was followed by the strong upregulation of AMP genes9. In cultured cells of Mamestra brassicae, induction of Hsp90, Hsp70, Hsp20.7, and Hsp19.7 was caused by halogenated pyrrole chlorfenapyr but not by other insecticides from different groups, such as pyrethroids, insect growth regulators, organophosphates, carbamates and trithians56. In contrast, Nazir et al.57 and Yoshimi et al.58 demonstrated significant induction of Hsp70 expression in guts of D. melanogaster and in whole bodies of Chironomus yoshimatsui after treatment with organophosphate pesticides and pyrethroids. Chen et al. 59 showed that neonicotinoid imidacloprid caused insignificant upregulation of Hsp70 in whole bodies of Colorado potato beetle larvae under optimal temperature (25 °C) and slight downregulation in response to the insecticide under high temperature (43 °C). Thus, the change in expression of HSPs may depend on the insecticide group, insect taxa and environment. However, it appears that neurotoxic insecticides do not cause significant change in expression of HSPs in Colorado potato beetles.

Importantly, the combined treatment (fungus + avermectins) did not lead to an additional decrease in microbiota diversity and increase in the bacterial load compared to the single treatments. In contrast, the fungus inhibited the elevation of the enterobacteria load with the combined treatment (Fig. 4). Joint treatment with fungus and avermectins did not lead to any additional effects on ROS generation and Hsp90, Dorsal-like and NF-kB-like gene expression levels, although a stronger enhancement of Att34 gene expression was observed. Interestingly, fungal infection prevented the downregulation of Stat caused by avermectins (Fig. 5). It is likely that fungal infection may regulate the proliferation of bacteria after treatment with additional factors, such as insecticides. Regulation of insect bacterial communities by entomopathogenic fungi was observed in the final stages of mycoses owing to fungal secondary metabolites60, although it was not observed at the initial stages. We surmise that the regulation of bacterial load by fungi after combined treatment may be mediated by host immune reactions, particularly the regulation of the Att34 and Stat genes.

The JAK-STAT pathway is activated by cytokines produced after damage to the gut epithelium, and this pathway participates in AMP production, as shown in Drosophila26,29. Upregulation of JAK-STAT pathway genes was observed in the gut of Bombyx mori after infection with different gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria61. In addition, JAK-STAT is involved in the insect antifungal response27,28. A decrease in the bacterial load under the combined action of fungus and avermectins (compared to action of avermectins alone) may have been caused by preventing JAK-STAT downregulation by fungus. We hypothesize that this effect may be caused by a systemic response of larvae to fungal infection, as demonstrated for mosquitoes by Ramirez et al. 27. To generate such evidence, it is necessary to analyze JAK-STAT gene expression in different tissues (e.g., cuticle, fat body, and hemocytes) after fungal infection of Colorado potato beetle, as well as investigating the effects of JAK-STAT silencing on bacterial communities.

In this study, considering the processes that occur in the midgut, we did not find direct confirmation that avermectins may promote fungal infection, as indicated in studies on the hemolymph and cuticle of the beetle39. However, we observed another effect in which fungal infection impeded the detoxification response to avermectins. In particular, M. robertsii infection prevented the activation of GST and EST in the midgut in response to avermectin treatment. EST and GST are involved in resistance to avermectins. Increased GST and EST levels were observed in arthropod lines that demonstrated resistance to this insecticide62–64, and inhibition of the detoxification enzymes led to an increase in susceptibility to abamectin51,65–67. In particular, direct silencing of GSTz2 expression increased the susceptibility of the fruit fly Bactrocera dorsalis to abamectin67. In Colorado potato beetle larvae, inhibition of esterases by S,S,S-tributyl phosphorotrithioate led to a fivefold increase in susceptibility to abamectin, and inhibition of GST by diethyl maleate caused a twofold increase in susceptibility to this insecticide68. Moreover, the inhibition of esterase activity may increase insect susceptibility to bacterial toxins35. Thus, blocking detoxification enzyme activation in Colorado potato beetle gut by the fungus may lead to increased toxic effects of avermectins, which may lead to general physiological consequences, such as a delay in development, weakening of cellular immunity and changes in the thickness and biochemical properties of integuments39,40,69. These disruptions are crucial to the susceptibility of Colorado potato beetle to Metarhizium and Beauveria69,70. It is likely that both direct and inverse effects between fungal infection and avermectins may occur in the investigated system and may lead to the formation of a "vicious circle" in which avermectins promote fungal infection (in the cuticle and hemolymph), and this infection increases the toxic effect of avermectins (in the gut). These interactions may cause a synergistic effect between the fungus and the avermectins. It should be noted that similar alterations of the detoxification enzyme activities under the combined action of M. robertsii and avermectins were established on mosquito Aedes aegypti larvae at the initial stages of mycosis and toxicosis71, which is in keeping with our hypothesis.

In conclusion, this study is the first to show alterations in the gut immune reactions and bacterial community of Colorado potato beetle after treatment with fungal infection, insecticide and both. We demonstrated that a decrease in ROS production and elevation of Serratia proliferation occurred in the midgut of beetle larvae after topical treatment with fungus, which is consistent with the results obtained for mosquitoes7 and supports the hypothesis that immune reactions are prioritized between the integuments and gut under the development of fungal infections. Avermectin toxicosis led to a significant shift in bacterial communities toward enterobacterial prevalence and activation of the Toll and IMD immune-signaling pathways. However, downregulation of stress-regulated genes (Hsp90) and the JAK-STAT pathway was observed after treatment with this insecticide, which may be attributable to the disruption of receptors containing G-protein. Significant interactions between fungal infection and avermectin toxicosis were demonstrated for the gut immune responses and bacterial load. In particular, fungal infection impeded the elevation of enterobacteria, downregulation of STAT and activation of detoxification enzymes caused by avermectins. Blocking the detoxification response by fungi may be one of the mechanisms governing the synergy between M. robertsii and avermectins. Further research may investigate the temporal-spatial distribution of immune reactions in Colorado potato beetles under mycoses and toxicoses.

Methods

Fungi, insects, and insecticide

Colorado potato beetle larvae were collected from private potato fields in the steppe zone of Western Siberia (53° 44′ N, 78° 02′ E) in July 2018. Strain P-72 M. robertsii (GenBank no. KP172147) from the microorganism collection of the Institute of Systematics and Ecology of Animals, Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Science (SB RAS) was used in the experiments. Conidia were grown on autoclaved millet as described previously69. For the infection, conidia were suspended in a water-Tween 20 solution (0.03%) to a final concentration 106 conidia/mL. The concentration was determined using a Neubauer hemocytometer. The viability of the conidia was checked by plating on Saburoad dextrose agar. The germination of the conidia was > 95%. The industrial product Actarophyt 0.2% (Enzyme, Vinnytsia, Ukraine) with a complex of natural avermectins produced by Streptomyces avermitilis (http://enzim.biz) was used. Actarophyt dissolved in distilled water to 0.0054% (half-lethal concentration) was used for the treatment. Selected concentrations of conidia and avermectins enable synergy between these agents39,40.

Procedure of treatments and bioassay

Larvae (4–6 h after molting at the fourth instar) were infected with fungus by being dipped for 15 s into a water-Tween suspension of conidia. Control larvae were treated with a conidia-free water-Tween solution. After inoculation, the larvae were immediately placed on Solanum tuberosum leaves treated with either the avermectin solution or distilled water. The following four treatments were set up: Control, Fungus, Avermectins and Fungus + Avermectins. Larvae were maintained in 300 mL ventilated plastic containers (10 larvae in each) with potato foliage (6 g per container daily). To prevent plant desiccation, leaf footstalks were inserted in 2.5 mL tubes that were plugged with damp cotton. Containers were exposed at 25–26 °C, 25–30% RH and 14:10 h photoperiod. Insect mortality was registered daily for 10 days. At least 60 larvae of each treatment were used for the bioassay.

Midgut bacterial communities

At 48 h after treatment, the larvae midguts with contents were isolated and frozen in liquid nitrogen (5 midguts per sample) and stored at − 80 °C. Total DNA was extracted using the DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (QIAGEN). Bead beating was performed using a TissueLyser II (QIAGEN) for 10 min at 30 Hz. The V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA genes was amplified with the primer pair 343F and 806R as described early72. The 16S libraries were sequenced with 2 × 300 bp paired-ends reagents on the MiSeq platform (Illumina) at the SB RAS Genomics Core Facility (Institute of Chemical Biology and Fundamental Medicine SB RAS, Novosibirsk, Russia).

Raw sequences were analyzed with the UPARSE pipeline73 using USEARCH v11.0.667. The UPARSE pipeline included paired read merging, read quality filtering, length trimming, identical read merging (dereplication), discarding singleton reads, removing chimeras and OTU clustering using the UPARSE algorithm74. The OTU sequences were assigned a taxonomy using the SINTAX75 and 16S RDP training set v16 as a reference76. The OTUs related to chloroplast 16S rDNA were removed from the final data set and analyzed separately.

The final data set included 507,752 reads (31,734 ± 2440 per sample) (see Appendix 1). Rarefaction and extrapolated curves were generated using the “iNEXT” package77 and showed trends approaching the saturation plateau, which indicated that enough reads were included (Appendix 2, Fig. S2). Alpha diversity metrics were calculated in Usearch.

Analysis of CFU count

Colorado potato beetle midguts with contents (1 sample = 3 midguts) were homogenized and suspended in sterile 150 mM NaCl solution. Aliquots of 100 µL suspension (5 × 10–2–5 × 10–5) were inoculated onto the surface of selective media. The CFUs of Lactococcus were determined by plating onto bile esculin azide agar M493 (HiMedia, Mumbai, India); those of Enterobacteriaceae (excluding Serratia) were determined by plating onto endo agar M029; and those of Serratia were determined by plating onto Serratia differential medium M1288 (same manufacturer). Petri dishes with bacteria were incubated at 26 °C for 48 h. Then, the bacterial colonies were counted based on the morphological characteristics. At least 5 replicates for each treatment were used for analysis.

qPCR analysis of immunity-, stress- and ROS-related genes

Colorado potato beetle midguts were isolated at 48 h after treatment, dissected in PBS and cleaned and washed to remove the contents of the gut lumen. All procedures were performed according to previously described techniques9. Briefly, five midguts were pooled in one sample, and six biological replicates per treatment were used in the analysis. Total RNA was extracted by QIAzol Lysis Reagent for DNA, RNA and protein isolation (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR analysis was performed in three technical replicates under the following conditions: 95 °C for 3 min followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 15 s and annealing and elongation at 62 °C for 30 s; and generation of melting curves (70–90 °C). Two genes of Leptinotarsa decemlineata were used as reference genes: 60S ribosomal protein L4 (Rp4) and ADF-ribosylation factor-like protein 1 (Arf1). These genes and primer sequences were from the work of Shi et al. 78 and were more stable in our investigated system. The relative expression of six genes of interest (Dorsal-like, NF-kB-like, Stat, Att34, Hsp90, and Mesh) was assayed. Primer sequences are provided in Appendix 2, Table S2. Primer properties were identified by IDT OligoAnalyzer 3.1 (http://eu.idtdna.com/calc/analyzer).

EPR analysis of ROS production

Spin trapping using 1-hydroxy-3-carboxy-pyrrolidine (CP-H) has been used to measure the rate of ROS formation79. CP-H rapidly reacts with oxygen-centered free radicals, including superoxide, and some molecular oxidants to generate stable nitroxide that can be detected by EPR. In contrast, the reaction with oxygen, hydrogen peroxide and organic peroxides is very slow80.

ROS measurement was performed as previously described79 with modifications to the sample preparation. Colorado potato beetle midguts were isolated at 48 h after treatment, dissected in PBS and cleaned and washed to remove the contents of the gut lumen. The sample contained 5 guts homogenized in 50 μL sodium phosphate buffer (50 mM with 0.1 mM DTPA, pH 7.2), and 1 mM CP-H was placed in a 50 μL glass capillary tube for EPR measurement. Ten samples were analyzed in each treatment.

Detoxification enzymes

To measure GST and EST activity, we utilized the technique of Habig et al.81 and Prabhakaran and Kamble82 with minor modifications. In brief, one sample included 2 guts that were homogenized in 100 μL sodium phosphate buffer (0.1 M pH 7.2) (PBS) with phenylthiourea (4 mg/mL) and centrifuged at 10,000g for 10 min. The GST activity was estimated by measuring the generation of 5-(2,4-dinitrophenyl)-glutathione at a wavelength of 340 nm. The EST level was estimated according to p-nitrophenyl acetate hydrolysis at 410 nm. The protein concentration was estimated using the Bradford method83. Bovine serum albumin was used for the calibration curve. At least 15 samples were analyzed in each treatment.

Serratia identification and their influence on susceptibility to fungus

Representative colonies from Serratia differential medium were selected and passaged three times on tryptose agar medium. Bacterial strains were identified as previously described9 by sequencing a 1308-bp fragment of the 16S rRNA gene using primers 27F 5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′ and 1492R 5′-CCCTACGGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3. The obtained 16S rRNA gene sequences were compared against GenBank-available sequences from the type material (Appendix 2, Table S1).

For the bioassay, potato leaves were dipped in suspensions of Serratia isolates (109 propagules/mL) or distilled water (controls) and dried at 30 m under 25 °C. Larvae were dipped in the suspension of M. robertsii (106 conidia/mL) or conidia-free water-Tween solution and immediately placed on treated or untreated potato leaves. The following four treatments were used: Control, Serratia, Fungus, and Serratia + Fungus. Larvae were maintained as described above. Mortality was measured for 10 days. At least 40 larvae (1 replicate = 10 larvae) were used in each treatment.

Statistical analyses

Data analyses were conducted using PAST 384, STATISTICA 8 (StatSoft Inc., USA), SigmaStat 3.1 (Systat Software Inc., USA), and AtteStat 12.585. Data were checked for a normal distribution using the Shapiro–Wilk W test. Normally distributed data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. For abnormally distributed data, we used a nonparametric equivalent of the two-way ANOVA Scheirer–Ray–Hare test86, followed by Dunnʼs post-test. The synergistic effects in mortality were detected by comparing the expected and observed mortality as described by Robertson and Preisler87. In addition, the log-rank test was applied for estimating differences in the mortality dynamics. Data on the plots are presented as the arithmetic means and standard errors.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. V.A. Shilo (Karasuk Biological Station of IS&EA SB RAS) for providing assistance with the organization of the experiments. The work was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (project no. 18-34-20060). The work on bacteria Serratia isolation, identification and conservation was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project no. 19-76-00032).

Author contributions

Experimental design (V.Y.K., V.V.G., O.Y.), conducting the experiments (V.Y.K., U.R., O.P., O.Y., Y.A., A.K., T.A., Y.V., I.S.), data analysis (V.Y.K., M.K., U.R., A.K.), writing the manuscript (V.Y.K., U.R., N.K., M.K.), and obtaining funding (O.Y., O.P.).

Data availability

The MiSeq data were deposited in GenBank under the study accession number PRJNA613617. The sequences of the 16S rRNA genes of the Serratia strains were deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers MT256278, MT256279, MT256306 and MT256307. Experimental data are presented in Appendix 1.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-020-80565-x.

References

- 1.Boucias DG, Zhou YH, Huang SS, Keyhani NO. Microbiota in insect fungal pathology. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018;102:5873–5888. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-9089-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gomes AFF, Omoto C, Cônsoli FL. Gut bacteria of field-collected larvae of Spodoptera frugiperda undergo selection and are more diverse and active in metabolizing multiple insecticides than laboratory-selected resistant strains. J. Pest. Sci. 2020;93:833–851. doi: 10.1007/s10340-020-01202-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackburn MB, Gundersen-Rindal DE, Weber DC, Martin PAW, Farrar RR. Enteric bacteria of field-collected Colorado potato beetle larvae inhibit growth of the entomopathogens Photorhabdus temperata and Beauveria bassiana. Biol. Control. 2008;46:434–441. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2008.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mattoso TC, Moreira DDO, Samuels RI. Symbiotic bacteria on the cuticle of the leaf-cutting ant Acromyrmex subterraneus subterraneus protect workers from attack by entomopathogenic fungi. Biol. Lett. 2012;8:461–464. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2011.0963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou F, et al. Repressed Beauveria bassiana infections in Delia antiqua due to associated microbiota. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019;75:170–179. doi: 10.1002/ps.5084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang F, et al. The interactions between gut microbiota and entomopathogenic fungi: A potential approach for biological control of Blattella germanica (L.) Pest Manag. Sci. 2018;74:438–447. doi: 10.1002/ps.4726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei G, et al. Insect pathogenic fungus interacts with the gut microbiota to accelerate mosquito mortality. PNAS. 2017;114:5994–5999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1703546114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu L, et al. Gut microbiota in an invasive bark beetle infected by a pathogenic fungus accelerates beetle mortality. J. Pest. Sci. 2019;92:343–351. doi: 10.1007/s10340-018-0999-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polenogova OV, et al. Parasitoid envenomation alters the Galleria mellonella midgut microbiota and immunity, thereby promoting fungal infection. Sci. Rep. 2019 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40301-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.James RR, Xu J. Mechanisms by which pesticides affect insect immunity. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2012;109:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu F, et al. Chapter seven—exploiting innate immunity for biological pest control. Adv. Insect Physiol. 2017;52:199–230. doi: 10.1016/bs.aiip.2017.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quintela ED, McCoy CW. Conidial attachment of Metarhizium anisopliae and Beauveria bassiana to the larval cuticle of Diaprepes abbreviatus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) treated with imidacloprid. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1998;72:220–230. doi: 10.1006/jipa.1998.4791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furlong MJ, Groden E. Evaluation of synergistic interactions between the Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) pathogen Beauveria bassiana and the insecticides, imidacloprid, and cyromazine. J. Econ. Entomol. 2001;94:344–356. doi: 10.1603/0022-0493-94.2.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zibaee A, Bandani AR, Malagoli D. Methoxyfenozide and pyriproxifen alter the cellular immune reactions of Eurygaster integriceps Puton (Hemiptera: Scutelleridae) against Beauveria bassiana. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2012;102:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2011.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jia M, et al. Biochemical basis of synergism between pathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae and insecticide chlorantraniliprole in Locusta migratoria (Meyen) Sci. Rep. 2016 doi: 10.1038/srep28424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ali S, et al. Toxicological and biochemical basis of synergism between the entomopathogenic fungus Lecanicillium muscarium and the insecticide matrine against Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) Sci. Rep. 2017;7:14. doi: 10.1038/srep46558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krukov VY, et al. Effects of fluorine-containing usnic acid and fungus Beauveria bassiana on the survival and immune-physiological reactions of Colorado potato beetle larvae. Pest Manag. Sci. 2018;74:598–606. doi: 10.1002/ps.4741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin Y, et al. Imidacloprid pesticide regulates Gynaikothrips uzeli (Thysanoptera: Phlaeothripidae) host choice behavior and immunity against Lecanicillium lecanii (Hypocreales: Clavicipitaceae) J. Econ. Entomol. 2018;111:2069–2075. doi: 10.1093/jee/toy209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alves SN, Serrao JE, Melo AL. Alterations in the fat body and midgut of Culex quinquefasciatus larvae following exposure to different insecticides. Micron. 2010;41:592–597. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noskov YA, et al. A neurotoxic insecticide promotes fungal infection in Aedes aegypti larvae by altering the bacterial community. Microb. Ecol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00248-020-01567-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vallet-Gely I, Lemaitre B, Boccard F. Bacterial strategies to overcome insect defences. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008;6:302–313. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiao X, et al. A Mesh-Duox pathway regulates homeostasis in the insect gut. Nat. Microbiol. 2017 doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lambeth JD. Nox enzymes and the biology of reactive oxygen. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004;4:181–189. doi: 10.1038/nri1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ha EM, Oh CT, Bae YS, Lee WJ. A direct role for dual oxidase in Drosophila gut immunity. Science. 2005;310:847–850. doi: 10.1126/science.1117311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim S-H, Lee W-J. Role of DUOX in gut inflammation: Lessons from Drosophila model of gut-microbiota interactions. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2014 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buchon N, Silverman N, Cherry S. Immunity in Drosophila melanogaster—from microbial recognition to whole-organism physiology. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014;14:796–810. doi: 10.1038/nri3763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramirez JL, Dunlap CA, Muturi EJ, Barletta ABF, Rooney AP. Entomopathogenic fungal infection leads to temporospatial modulation of the mosquito immune system. PLoS Neglect. Trop. Dis. 2018 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dong YM, Morton JC, Ramirez JL, Souza-Neto JA, Dimopoulos G. The entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana activate toll and JAK-STAT pathway-controlled effector genes and anti-dengue activity in Aedes aegypti. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2012;42:126–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buchon N, Broderick NA, Poidevin M, Pradervand S, Lemaitre B. Drosophila intestinal response to bacterial infection: Activation of host defense and stem cell proliferation. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcia-Gomez BI, et al. Insect Hsp90 chaperone assists Bacillus thuringiensis Cry toxicity by enhancing protoxin binding to the receptor and by protecting protoxin from gut protease degradation. Mbio. 2019;10:12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02775-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao L, Jones WA. Expression of heat shock protein genes in insect stress responses. Invertebr. Surv. J. 2012;9:93–101. [Google Scholar]

- 32.King AM, MacRae TH. Insect heat shock proteins during stress and diapause. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2015;60:59–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-011613-162107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gunning RV, Dang HT, Kemp FC, Nicholson IC, Moores GD. New resistance mechanism in Helicoverpa armigera threatens transgenic crops expressing Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac toxin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:2558–2563. doi: 10.1128/aem.71.5.2558-2563.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panini M, Manicardi GC, Moores GD, Mazzoni E. An overview of the main pathways of metabolic resistance in insects. Invertebr. Surv. J. 2016;13:326–335. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grizanova EV, Krytsyna TI, Surcova VS, Dubovskiy IM. The role of midgut nonspecific esterase in the susceptibility of Galleria mellonella larvae to Bacillus thuringiensis. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2019.107208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Serebrov VV, et al. The effect of entomopathogenic fungi on the activity of detoxicating enzymes of larvae of bee pyralid Galleria mellonella L. (Lepidoptera, Pyralidee) and the role of detoxicating enzymes in the formation of the insect' resistance to entomopathogenic fungi. Izvest. Akad. Nauk. Seriia Biol. 2006;2:712–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han P, et al. Transcript and protein profiling analysis of the destruxin a-induced response in larvae of Plutella xylostella. PLoS One. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alyokhin A, et al. The Red Queen in a potato field: Integrated pest management versus chemical dependency in Colorado potato beetle control. Pest Manag. Sci. 2015;71:343–356. doi: 10.1002/ps.3826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tomilova OG, et al. Immune-physiological aspects of synergy between avermectins and the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium robertsii in Colorado potato beetle larvae. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2016;140:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akhanaev YB, et al. Combined action of the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium robertsii and avermectins on the larvae of the colorado potato beetle Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say) (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae) Entomol. Rev. 2017;97:158–165. doi: 10.1134/S0013873817020026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hackett KJ, et al. Spiroplasma leptinotarsae sp nov, a mollicute uniquely adapted to its host, the Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1996;46:906–911. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-4-906. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muratoglu H, Demirbag Z, Sezen K. The first investigation of the diversity of bacteria associated with Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) Biologia. 2011;66:288–293. doi: 10.2478/s11756-011-0021-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chung SH, et al. Herbivore exploits orally secreted bacteria to suppress plant defenses. PNAS. 2013;110:15728–15733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308867110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chung SH, et al. Host plant species determines symbiotic bacterial community mediating suppression of plant defenses. Sci. Rep. 2017 doi: 10.1038/srep39690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang J, et al. Geographically isolated Colorado potato beetle mediating distinct defense responses in potato is associated with the alteration of gut microbiota. J. Pest. Sci. 2020;93:379–390. doi: 10.1007/s10340-019-01173-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kryukov VY, et al. Bacterial decomposition of insects post-Metarhizium infection: Possible influence on plant growth. Fungal Biol. 2019;123:927–935. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2019.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dubovskiy I, et al. Immuno-physiological adaptations confer wax moth Galleria mellonella resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis. Virulence. 2016;7:860–870. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2016.1164367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang W, Keyhani NO, Zhang H, Cai K, Xia Y. Inhibitor of apoptosis-1 gene as a potential target for pest control and its involvement in immune regulation during fungal infection. Pest Manag. Sci. 2020;76:1831–1840. doi: 10.1002/ps.5712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruiz-Sanchez E, O'Donnell MJ. Effects of the microbial metabolite destruxin a on ion transport by the gut and renal epithelia of Drosophila melanogaster. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2012;80:109–122. doi: 10.1002/arch.21023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rios-Moreno A, Garrido-Jurado I, Raya-Ortega MC, Quesada-Moraga E. Quantification of fungal growth and destruxin A during infection of Galleria mellonella larvae by Metarhizium brunneum. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2017;149:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clark JM, Scott JG, Campos F, Bloomquist JR. Resistance to avermectins—extent, mechanisms, and management implications. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1995;40:1–30. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.40.010195.000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Viktorov AV, Yurkiv VA. Effect of ivermectin on function of liver macrophages. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2003;136:569–571. doi: 10.1023/B:BEBM.0000020206.23474.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gurevich VV, Gurevich EV. Molecular mechanisms of GPCR signaling: A structural perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:17. doi: 10.3390/ijms18122519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hilger D, Masureel M, Kobilka BK. Structure and dynamics of GPCR signaling complexes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2018;25:4–12. doi: 10.1038/s41594-017-0011-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Royet J, Gupta D, Dziarski R. Peptidoglycan recognition proteins: Modulators of the microbiome and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011;11:837–851. doi: 10.1038/nri3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sonoda S, Tsumuki H. Induction of heat shock protein genes by chlorfenapyr in cultured cells of the cabbage armyworm, Mamestra brassicae. Pesticide Biochem. Physiol. 2006;89:185–189. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2007.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nazir A, Mukhopadhyay I, Saxena D, Chowdhuri DK. Chlorpyrifos-induced hsp70 expression and effect on reproductive performance in transgenic Drosophila melanogaster (hsp70-lacZ) Bg 9. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2001;41:443–449. doi: 10.1007/s002440010270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yoshimi T, et al. Activation of a stress-induced gene by insecticides in the midge, Chironomus yoshimatsui. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2002;16:10–17. doi: 10.1002/jbt.10018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen J, Kitazumi A, Alpuerto J, Alyokhin A, de los Reyes B. Heat-induced mortality and expression of heat shock proteins in Colorado potato beetles treated with imidacloprid. Insect Sci. 2015;23:548–554. doi: 10.1111/1744-7917.12194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fan YH, et al. Regulatory cascade and biological activity of Beauveria bassiana oosporein that limits bacterial growth after host death. PNAS. 2017;114:E1578–E1586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616543114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu S, et al. Expression of antimicrobial peptide genes in Bombyx mori gut modulated by oral bacterial infection and development. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2010;34:1191–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang L, Wu Y. Cross-resistance and biochemical mechanisms of abamectin resistance in the B-type Bemisia tabaci. J. Appl. Entomol. 2007;131:98–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0418.2006.01140.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen, Q., Lu, F. P., Xu, X. L. & Lu, H. Relationships between abamectin resistance and the activities of detoxification enzymes in the cotton bollworm, Helicoverpa armigera. Advances in Biomedical Engineering. International Conference on Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering. 136–139 (PEOPLES R CHINA, 2011).

- 64.Liao C-Y, et al. Characterization and functional analysis of a novel glutathione S-transferase gene potentially associated with the abamectin resistance in Panonychus citri (McGregor) Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2016;132:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu G, Miyata T, Kang CY, Xie LH. Insecticide toxicity and synergism by enzyme inhibitors in 18 species of pest insect and natural enemies in crucifer vegetable crops. Pestic. Manag. Sci. 2007;63:500–510. doi: 10.1002/ps.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rameshgar F, Khajehali J, Nauen R, Dermauw W, Van Leeuwen T. Characterization of abamectin resistance in Iranian populations of European red mite, Panonychus ulmi Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae) Crop Protect. 2019;125:104903. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2019.104903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tang G-H, et al. The Transcription factor mafB regulates the susceptibility of Bactrocera dorsalis to abamectin via GSTz2. Front. Physiol. 2019 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Argentine JA, Clark JM, Lin H. Genetics and biochemical-mechanisms of abamectin resistance in 2 isogenic strains of Colorado potato beetle. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 1992;44:191–207. doi: 10.1016/0048-3575(92)90090-m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tomilova OG, et al. Changes in antifungal defence systems during the intermoult period in the Colorado potato beetle. J. Insect Physiol. 2019;116:106–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2019.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Furlong MJ, Groden E. Starvation induced stress and the susceptibility of the Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata, to infection by Beauveria bassiana. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2003;83:127–138. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2011(03)00066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Noskov YA, et al. Combined effect of the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium robertsii and avermectins on the survival and immune response of Aedes aegypti larvae. Peerj. 2019;7:23. doi: 10.7717/peerj.7931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brouchkov A, et al. Bacterial community in ancient permafrost alluvium at the Mammoth Mountain (Eastern Siberia) Gene. 2017;636:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Edgar RC. UPARSE: Highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:996–998. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Edgar RC. UNOISE2: Improved error-correction for Illumina 16S and ITS amplicon sequencing. bioRxiv. 2016 doi: 10.1101/081257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Edgar RC. SINTAX, a simple non-bayesian taxonomy classifier for 16S and ITS sequences. bioRxiv. 2016 doi: 10.1101/074161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/aem.00062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hsieh TC, Ma KH, Chao A. iNEXT: An R package for rarefaction and extrapolation of species diversity (Hill numbers) Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016;7:1451–1456. doi: 10.1111/2041-210x.12613. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shi X-Q, et al. Validation of reference genes for expression analysis by quantitative real-time PCR in Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say) BMC Res. Notes. 2013;6:93–93. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Slepneva IA, Komarov DA, Glupov VV, Serebrov VV, Khramtsov VV. Influence of fungal infection on the DOPA-semiquinone and DOPA-quinone production in haemolymph of Galleria mellonella larvae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;300:188–191. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02766-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dikalov SI, Polienko YF, Kirilyuk I. Electron paramagnetic resonance measurements of reactive oxygen species by cyclic hydroxylamine spin probes. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018;28:1433–1443. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Habig WH, Pabst MJ, Jakoby WB. Glutathione S-transferases. The first enzymatic step in mercapturic acid formation. J. Biol. Chem. 1974;249:7130–7139. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)42083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Prabhakaran SK, Kamble ST. Purification and characterization of an esterase isozyme from insecticide resistant and susceptible strains of german-cockroach, Blattella germanica (L.) Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1995;25:519–524. doi: 10.1016/0965-1748(94)00093-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bradford MM. Rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hammer Ø, Harper DAT, Ryan PD. PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001;4:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gaidyshev IP. Solving Scientific and Engineering Problems by Means of Excel, VBA, and C++ St. Petersburg: BKhV-Peterburg; 2004. p. 512. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Scheirer CJ, Ray WS, Hare N. The analysis of ranked data derived from completely randomized factorial designs. Biometrics. 1976;32:429–434. doi: 10.2307/2529511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Robertson JL, Preisler HK. Pesticide Bioassays with Arthropods. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1992. p. 127. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The MiSeq data were deposited in GenBank under the study accession number PRJNA613617. The sequences of the 16S rRNA genes of the Serratia strains were deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers MT256278, MT256279, MT256306 and MT256307. Experimental data are presented in Appendix 1.