Abstract

Patients with anti-interferon (IFN)-γ autoantibodies have weakened immune defenses against intracellular pathogens. Because of its low incidence and non-specific symptoms, diagnosis of anti-IFN-γ autoantibody syndrome is difficult to establish during the early stages of infection. Here, we report a patient with high titers of serum anti-IFN-γ autoantibodies suffering from opportunistic infections. The patient presented with intermittent fever for 2 weeks. During his first hospitalization, he was diagnosed with Talaromyces marneffei pulmonary infection and successfully treated with antifungal therapy. However, multiple cervical lymph nodes subsequently became progressively enlarged. Mycobacterium abscessus infection was confirmed by positive cervical lymph node tissue cultures. High-titer serum anti-IFN-γ antibodies were also detected. Following anti-M. abscessus therapy, both his symptoms and lymph node lymphadenitis gradually improved. Anti-IFN-γ autoantibody syndrome should be considered in adult patients with severe opportunistic coinfections in the absence of other known risk factors.

Keywords: Case report, anti-interferon-γ autoantibodies, Talaromyces marneffei, non-tuberculous mycobacteria, adult onset immunodeficiency, Mycobacterium abscessus

Background

Interferon (IFN)-γ is produced mainly by Th1 cells, natural killer cells, and CD8+ T cells. The IFN-γ/interleukin-12/tumor necrosis factor-α axis plays a crucial role in host defense against intracellular pathogens.1,2 Autoantibodies against IFN-γ can inhibit IFN-γ-dependent signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 phosphorylation in patients with adult-onset susceptibility to opportunistic infections.3 Because of its low incidence and non-specific symptoms and manifestations, early diagnosis of adult-onset anti-IFN-γ autoantibody syndrome is challenging.4

Here, we report a patient with high titer serum anti-IFN-γ autoantibodies who suffered from pulmonary Talaromyces marneffei infection and infection of multiple lymph nodes by non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM). The details of this case may help clinicians to identify this syndrome and implement appropriate treatments early.

Case presentation

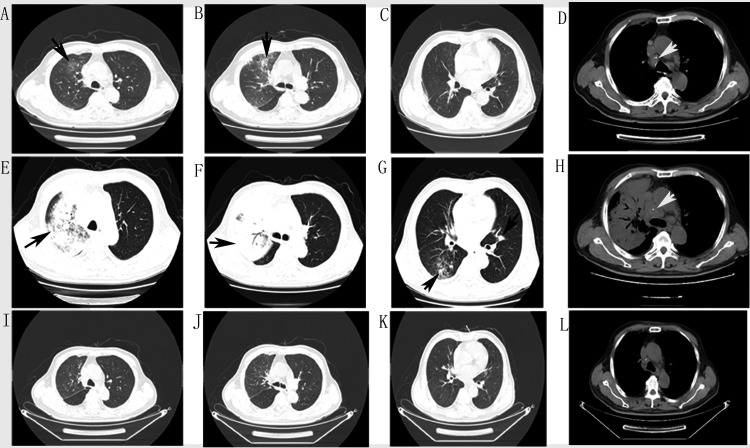

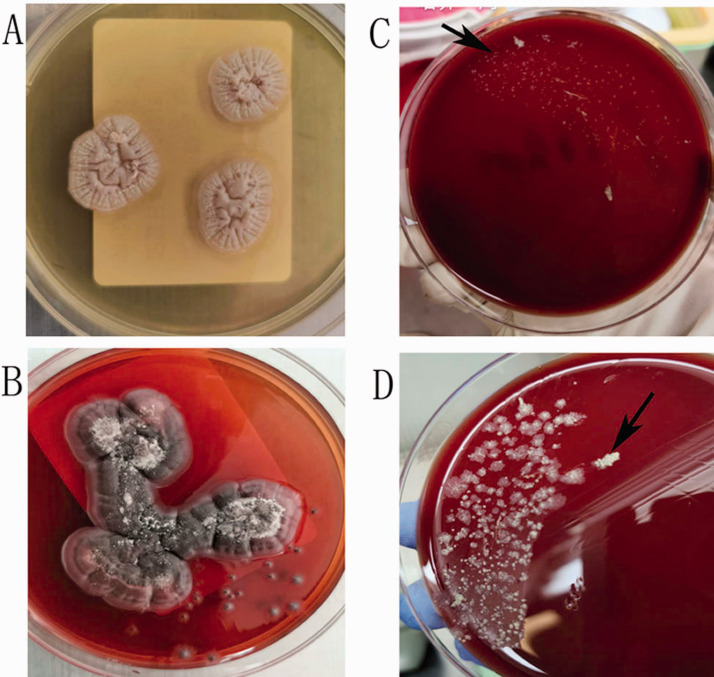

The patient was a 68-year-old man experiencing intermittent fever of unknown cause for 2 weeks. He had a history of hypertension (8 years), kidney stones, and cervical lymphadenopathy (1 year) but no familial medical history. He had not received any treatment for cervical lymphadenopathy. Physical examination revealed moist rales in the right lung and cervical lymph node enlargement. Laboratory tests showed increased white blood cells and chest computed tomography (CT) showed patchy infiltration in the right upper lobe with mediastinal lymph node enlargement (Figure 1; 3 December 2019). Empirical treatment with cephalosporin was ineffective, and his symptoms recurred along with a central necrotic body rash. A repeat chest CT (17 December 2019) showed aggravated alveolar consolidation in the anterior segment of the right upper lobe, scattered infiltration in the right lower lobe, slight patchy infiltration in the left lingular bronchus, and multiple mediastinal lymphadenopathies (Figure 1). Bronchoscopy and endobronchial ultrasound were performed. Cytology showed nucleated cells counts of 400 × 105/L, neutrophil percentage of 85%, and lymphocyte percentage of 5%. Galactomannan was 0.11 pg/mL and cryptococcal capsular antigen tests were negative in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Metagenomic next-generation sequencing and culture demonstrated the presence of T. marneffei in biopsy tissue of the right upper lobe (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Chest computed (CT) images at different times. (A–D) Chest CT on 3 December 2019 showed patchy infiltration in the right upper lobe (black arrows) and mediastinal lymph node enlargement (white arrows). (E–H) Chest CT on 17 December 2019 showed exacerbated infiltration and alveolar consolidation in the left upper lobe, new patchy infiltration in the right lower lobe and left lingular bronchus (black arrows), and progressively enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes (white arrows). (I–L) Chest CT on 26 March 2020 showed marked improvement of pulmonary lesions after treatment.

Figure 2.

Cultures from lung biopsy and cervical lymph node homogenate. (A) Lung biopsy sample cultured on Sabouraud agar at 35°C showed round gray Talaromyces marneffei colonies. (B) Lung biopsy sample cultured on Sabouraud agar at 28°C showed a mycelial form producing a diffusible red pigment. Both (C) and (D) show colonies of Mycobacterium abscessus (black arrows) from cervical lymph nodes after incubation for 7 and 10 days, respectively.

Cervical lymph nodes were biopsied using fine-needle aspiration. Pathological findings demonstrated atrophy of lymphatic follicles with paracortical hyperplasia, neutrophil necrosis, histiocyte aggregation, and T-lymphocyte dysplasia. Analysis of T-cell receptor rearrangement ruled out lymphoma. Staining (acid-fast, periodic acid-Schiff, and periodic Schiff-methenamine) and microbial cultures of needle aspirate biopsies were negative for pathogens. Epstein–Barr virus-encoded small non-polyadenylated RNA 1 and 2 positive cells were < 5/high power field. The patient was diagnosed with pulmonary T. marneffei infection and administered voriconazole (0.2 g tablets) twice a day.

Taralomycosis is a rare condition in immunocompetent hosts. It has been previously described in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, connective tissue diseases and hematological malignancies. Serum autoantibodies [anti-nuclear antibody, anti-centromere antibody, anti-Sjögren's syndrome (SS)-A, anti-SS-B, anti-mitochondrial antibody, anti-myeloperoxidase antibody, perinuclear and cytoplasmic anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, and anti-proteinase 3 antibody] were within normal ranges. Human immunodeficiency virus serology was negative, and blood CD4+ T cell counts, (1, 3)-D glucan, galactomannan, immunoglobulin (Ig, including IgA, IgM, and total IgG), complement C3, complement C4, and pro-calcitonin were within normal reference ranges. Serum cryptococcal capsular antigen tests and blood tuberculosis infection T cell spot tests were negative. Serum anti-IFN-γ autoantibodies were assessed using a standard IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and showed a high titer of 1:500.

The patient was diagnosed with pulmonary taralomycosis and adult-onset immunodeficiency syndrome arising from anti-IFN-γ autoantibodies. He was followed up regularly in the clinic. Itraconazole (0.2 g capsule) was administered once a day instead of voriconazole because the patient developed a back and neck rash after 1 month of treatment.

After 3 months of antifungal treatment, his condition improved and a chest CT (26 March 2020) showed remarkable absorption of pulmonary consolidation. His mediastinal lymph nodes also reduced synchronously (Figure 1). However, the bilateral cervical, axillary, and supraclavicular lymph nodes became progressively enlarged.

Positron emission tomography (PET)-CT imaging revealed bilateral cervical and supraclavicular lymph node enlargement and necrosis, with glucose hypermetabolism [maximum standardized uptake value (SUV) 10.2], slight retroperitoneal lymph node enlargement with slight glucose hypermetabolism, and inflammation of the right lung.

To rule out lymphoma, bone marrow needle aspiration was performed. Cytology smears showed proliferation of bone marrow cells. The cervical lymph nodes were again biopsied using fine-needle aspiration. Pathological findings revealed neutrophil necrosis, infarcts and lymphocyte infiltration into necrotic areas. Acid-fast staining and Gomori methenamine silver staining were negative for pathogens.

An enlarged cervical lymph node was surgically excised. Pathological examinations demonstrated positive acid-fast staining in a granulomatous and suppurative inflammatory background. Periodic acid-Schiff and periodic Schiff-methenamine staining were negative. Mycobacterium abscessus was cultured and identified from tissue homogenates (Figure 2).

Finally, the patient was diagnosed with anti-IFN-γ autoantibody syndrome complicated by T. marneffei pulmonary infection and M. abscessus lymph node infection. According to drug sensitivity tests, anti-NTM therapy with clarithromycin and moxifloxacin was administered. The patient continuing this regimen and being actively followed up. Both his symptoms and cervical lymphadenitis gradually improved.

Discussion and conclusions

The interactions between IFN-γ and its receptors are critical for macrophage activation and inflammatory reactions. Adult onset immunodeficiency arising from anti-IFN-γ autoantibody is associated with opportunistic infections by mycobacteria, T. marneffei, Cryptococcus spp., Burkholderia spp. and other organisms in previously healthy patients.1–5

The trigger(s) eliciting anti-IFN-γ autoantibodies remain unknown. Recent studies showed that HLA-DRB1 and DQB1 alleles were associated with increased risk of developing anti-IFN-γ autoantibody.5,6 Although functional assessments of IFN-γ autoantibodies were not performed in this study, the high titers and mixed opportunistic infections observed in this patient were suggestive of adult-onset immunodeficiency syndrome.

Therapies for adult-onset immunodeficiency syndrome are directed against either infectious complications or the autoantibodies themselves.7 Rituximab, exogenous IFN-γ, plasmapheresis, and cyclophosphamide have been used to treat refractory infections8,9 and showed clinical benefits, although autoantibody levels following therapy were not routinely tested.

T. marneffei is the only dimorphic fungus of the genus Talaromyces (formerly Penicillium). Taralomycosis is a rare opportunistic infection typically affecting immunocompromised or immunosuppressed patients. The condition is rarely observed in immunocompetent patients and in non-endemic regions outside of Southeast Asia and southern China,10–12 such as Hangzhou, North Zhejiang Province, East China. Therefore, we first assessed the presence of underlying immune deficiencies in our patient such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, connective tissue diseases, hematological malignancies and immunosuppressants. In addition, we investigated and detected the presence of IFN-γ autoantibodies.

The symptoms of T. marneffei infection typically include fever, malaise, lymph node enlargement, skin eruptions, weight loss, dyspnea, diarrhea, and hemoptysis. Chest radiography typically reveals multiple nodules and/or consolidation, often involving the upper lobes.13

In our case, enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes, as well as pulmonary lesions, improved significantly following antifungal therapy. We speculate that the patient’s enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes, in addition to lung changes, were caused by taralomycosis. In addition, multiple cervical lymph nodes became progressively enlarged, suggesting different etiological factors.

Infections by NTM are common in patients with adult onset immunodeficiency syndrome caused by anti-IFN-γ autoantibody. Henkle et al.14 reported that 8.4% (28/334) of extra-pulmonary NTM infections affected the lymph nodes. Most patients affected by NTM infection have specific susceptibility factors,15 including structural lung damage or immunosuppressed status.16 In our case, NTM infection of multiple lymph nodes was attributed to the presence of anti-IFN-γ autoantibodies. NTM infections often progress to systemic dissemination in patients with anti-IFN-γ autoantibodies.14,17 In the present case, we failed to recognize underlying opportunistic infection by NTM until surgical biopsy of a cervical lymph node.

M. abscessus is a rapidly growing NTM that generally requires intravenous therapy and is difficult to eradicate. M. abscessus can be classified into three subspecies: M. abscessus subsp. abscessus, M. abscessus subsp. massiliense, and M. abscessus subsp. bolletii. The rates of response to antibiotic therapy differ for each of these subspecies. Therefore, subspecies identification is becoming increasingly important for NTM therapy.18

Giudice et al.19 reported that PET-CT has the potential to identify both pulmonary and lymph node NTM infection and showed an average SUV of 1.21 ± 0.29 (range: 0.90–1.70) in affected mediastinal lymph nodes. In the present case, PET-CT showed a maximum SUV of 10.2 in bilateral cervical lymph nodes. In our case, multiple lymphadenopathies, PET results and the primary reports from fine-needle aspiration biopsy could have indicated a hematological malignancy. Eventually, multiple myeloma and lymphoma were excluded upon thorough examinations.

Skin manifestations have been reported in patients with IFN-γ autoantibody syndrome complicated by disseminated taralomycosis or NTM infection.20 These manifestations can be divided into skin infections and reactive dermatitis. Our patient’s rash with central necrosis was characteristic of T. marneffei skin infection but disappeared prior to antifungal therapy. Therefore, there was insufficient evidence of T. marneffei skin infection, and the rash most likely reflected a reactive skin disorder.

In summary, anti-IFN-γ autoantibody syndrome should be considered in patients with severe opportunistic infections in the absence of other obvious risk factors. Disseminated T. marneffei and NTM are the most significant complications associated with anti-IFN-γ autoantibody syndrome.

Footnotes

Ethical statement and informed consent: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee at the Hangzhou First People’s Hospital of Zhejiang University and complied with the principles laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient provided written consent for the publication of this report.

Declaration of conflicting interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: Funding support for publication of this work was supplied by the Zhejiang Province Nature Science Funding Commission Social Development Project (grant no. LGF20H010005).

ORCID iD: Weizhong Jin https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9335-2336

References

- 1.Tang BS, Chan JF, Chen M, et al. Disseminated penicilliosis, recurrent bacteremic nontyphoidal salmonellosis, and burkholderiosis associated with acquired immunodeficiency due to autoantibody against gamma interferon. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2010; 17: 1132–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nekooie-Marnany N, Deswarte C, Ostadi V, et al. Impaired IL-12- and IL-23-mediated immunity due to IL-12Rβ1 deficiency in Iranian patients with mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease. J Clin Immunol 2018; 38: 787–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Browne SK, Holland SM. Anticytokine autoantibodies in infectious diseases: Pathogenesis and mechanisms. Lancet Infect Dis 2010; 10: 875–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Su SS, Zhang SN, Ye JR, et al. Disseminated Talaromyces marneffei and Mycobacterium avium infection accompanied Sweet’s syndrome in a patient with anti-interferon-γ autoantibodies: A case report. Infect Drug Resist 2019; 12: 3189–3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phoompoung P, Ankasekwinai N, Pithukpakorn M, et al. Factors associated with acquired anti-IFN-γ autoantibody in patients with nontuberculous mycobacterial infection. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0176342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watanabe M, Uchida K, Nakagaki K, et al. Anti-cytokine autoantibodies are ubiquitous in healthy individuals. FEBS Lett 2007; 581: 2017–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Browne SK. Anticytokine autoantibody-associated immunodeficiency. Annu Rev Immunol 2014; 32: 635–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Browne SK, Zaman R, Sampaio EP, et al. Anti-CD20 (rituximab) therapy for anti-interferon-γ autoantibody-associated nontuberculous mycobacterial infection. Blood 2012; 119: 3933–3939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laisuan W, Pisitkun P, Ngamjanyaporn P, et al. Prospective pilot study of cyclophosphamide as an adjunct treatment in patients with adult-onset immunodeficiency associated with anti-interferon-γ autoantibodies. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020; 7: ofaa035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y, Lin Z, Shi X, et al. Retrospective analysis of 15 cases of Penicillium marneffei infection in HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients. Microb Pathog 2017; 105: 321–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma W, Thiryayi SA, Holbrook M, et al. Rapid on-site evaluation facilitated the diagnosis of a rare case of Talaromyces marneffei infection. Cytopathology 2018; 29: 497–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang YG, Cheng JM, Ding HB, et al. Study on the clinical features and prognosis of penicilliosis marneffei without human immunodeficiency virus infection. Mycopathologia 2018; 183: 551–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Z, Tao F, Li Y, et al. Disseminated Penicillium marneffei infection recurrence in a non‑acquired immune deficiency syndrome patient: A case report. Mol Clin Oncol 2016; 5: 829–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shih DC, Cassidy PM, Perkins KM, et al. Extrapulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease surveillance – Oregon, 2014–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67: 854–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sood G, Parrish N. Outbreaks of nontuberculous mycobacteria. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2017; 30: 404–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sexton P, Harrison AC. Susceptibility to nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease. Eur Respir J 2008; 31: 1322–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshizawa K, Aoki A, Shima K, et al. Serum anti-interferon-γ autoantibody titer as a potential biomarker of disseminated non-tuberculous mycobacterial infection. J Clin Immunol 2020; 40: 399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koh WJ, Stout JE, Yew WW. Advances in the management of pulmonary disease due to Mycobacterium abscessus complex. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2014; 18: 1141–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Del Giudice G, Bianco A, Cennamo A, et al. Lung and nodal involvement in nontuberculous mycobacterial disease: PET/CT role. Biomed Res Int 2015; 2015: 353202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jutivorakool K, Sittiwattanawong P, Kantikosum K, et al. Skin manifestations in patients with adult-onset immunodeficiency due to anti-interferon-gamma autoantibody: A relationship with systemic infections. Acta Derm Venereol 2018; 98: 742–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]