Abstract

This review examines the factors that affect the decision-making process of parental couples evaluating prenatal screening and diagnostic tests. A systematic search was performed using PubMed and PsycInfo databases. The 46 included studies had to: investigate the decision-making process about prenatal testing; focus on tests detecting trisomy 21, 18, 13, and abnormalities of sex chromosomes; be published in English peer-reviewed journals. The decision-making process seems composed of different levels: an individual level with demographic, clinical, and psychological aspects; a contextual level related to the technical features of the test and the information received; a relational level involving family and society.

Keywords: clinical health psychology, genetic testing, health care, pregnancy, systematic review

Introduction

Pregnancy is characterized by many uncertainties for parents, and usually the primary one is the fetus’ health (Öhman et al., 2003). Many countries offer prenatal testing programs: prenatal screening is an option for all pregnant women who intend to assess the likelihood of having a fetus with a chromosomal abnormality, while prenatal diagnosis is indicated for women who are positive at the screening stage or have other risk factors, such as advanced maternal age (35 and older), family history of a genetic disorder, or abnormal ultrasound finding (Leiva Portocarrero et al., 2015). Screening tests offer an estimated risk calculation of fetal aneuploidy, diagnostic tests detect the actual presence of a genetic aneuploidy with a theoretical 100% accuracy (Sapp et al., 2010). Prenatal testing (both screening and diagnostic test) has the function of identifying fetuses with a high risk of developing genetic pathologies, including Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome), Trisomy 13 (Patau syndrome), Trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome), triploidy, and Turner syndrome.

Several procedures are available to obtain prenatal genetic information: the non-invasive combined first-trimester screen (cFTS) takes into account the mother’s age and weight, the fetal crown-rump length and nuchal translucency thickness measured by the ultrasound, and maternal serum biomarkers; the invasive diagnostic procedures include the chorionic villus sampling (CVS) and the amniocentesis, both of which carry a risk of miscarriage reported to be approximately 1:200 (Akolekar et al., 2015).

Since 2011, a new non-invasive prenatal screening test that uses fetal cell-free DNA (NIPT) obtained from circulating maternal blood is available (Lo et al., 1997). It can be performed starting from the 9th week of pregnancy, as it involves a single blood draw with a result turnaround time of about 2 weeks (Scott et al., 2018). NIPT holds no risk of miscarriage and offers clinical benefits over existing prenatal screening tests by detecting the presence of Trisomy 21 with high sensitivity (99.9%) and specificity (98%) (Birko et al., 2019; Metcalfe, 2018). Moreover, it carries a false positive rate of 0.09–0.12% (Yu et al., 2017), which is lower than other prenatal screening tests rates. However, NIPT is not covered by the publicly funded healthcare system and is not considered accurate enough to be sufficient for a diagnosis. Therefore, this test entails both benefits and concerns (Vanstone et al., 2018). Specifically, the advent of NIPT definitely enriched prenatal testing available to parental couples, but its higher costs and the impossibility of a diagnosis further entangle the complex decision-making process.

The uptake of prenatal screening and diagnosis has differed between societies despite the apparent similarity in set-up of the screening program. This might reflect differences in society’s attitude toward screening (i.e. if the screening is private or public, if it is self-paid or insurance-dependent), and in the individual’s attitude (Crombag et al., 2014).

When evaluating prenatal testing, women face a double burden, which includes the worries and the responsibilities for their own health and for their unborn baby. For these reasons, the choice is often complicated and emotionally distressing (Lobel et al., 2005). Reassurance about the health of the fetus, attitude toward abortion and test characteristics are examples of the key factors that play a role in the decision (Green et al., 2004; van den Berg et al., 2006). However, the relatively recent introduction of the NIPT as an alternative to other screening tests, could significantly impact on this decision-making process, making past review on the topic obsolete.

Therefore, the present systematic review aims at updating previous reviews (Crombag et al., 2013; Godino et al., 2013) not considering literature on the NIPT, for providing an in-depth examination of the factors that affect the decision-making process of parental couples when evaluating prenatal testing, including non-invasive (cFTS, NIPT) and invasive (CVS, amniocentesis) tests. Specifically, the purpose of this review is answering to the following questions: a) What are the decision-making factors associated with undergoing prenatal testing? b) Are different decision-making factors associated with different kinds of tests?

Methods

Study design and search strategy

Potentially eligible articles were systematically searched on PsycInfo and PubMed databases on 11th June 2020 using the following combinations of terms: “prenatal diagnosis,” “prenatal screening,” “prenatal genetic testing,” “invasive prenatal testing,” “non-invasive prenatal testing,” “amniocentesis,” “cell-free fetal DNA,” “chorion villus,” and “decision-making” (the full search strategy is available in Appendix 1). We limited the search to papers published since January 2011 (i.e. the introduction of NIPT) to ensure findings related to the current practice regarding prenatal testing.

We developed the following set of inclusion criteria for papers to be included in our review:

Studies had to report on primary research;

Studies had to be published in a peer-reviewed journal;

Studies had to be written in English;

Studies had to be quantitative or mixed-methods;

Studies had to address the decision-making process about prenatal testing of pregnant women or when available both parents;

Studies had to address prenatal testing that detect trisomy 21, 18, 13, and abnormalities of sex chromosomes.

Exclusion criteria were as follows:

Qualitative studies;

Studies that took into account only test uptake without analysis of the reasons for accepting or declining tests;

Studies implemented with decision support tools;

Studies focusing on healthcare professionals’ attitudes toward prenatal testing;

Retrospective studies;

Reviews of the literature.

We removed duplicates through Zotero software version 5.0. In the first stage, three independent researchers (FF, GP, VT) screened titles and abstracts of the papers found. In the second stage, the same researchers screened the full texts of all remaining studies to assess their eligibility and reference lists of these articles were screened. When discrepancies were identified between the researchers, they discussed the article in question to come to a consensus opinion.

Studies were not required to meet a quality threshold to be included in the review; however, the NIH Checklist for Study Quality Assessment (National Institutes of Health, 2014) was used to evaluate the methodological quality of the included studies, classifying them into good (8–10), fair (4–7) and poor (0–3) methodological rigor. In all studies, four items of the checklist were not applicable and were therefore excluded.

Data extraction

FF, GP, and VT participated in data extraction and analysis. The data consisted of the findings from both the results and discussion sections of the relevant studies.

The authors extracted data about: publication year, country of study, participant information, risk level of the pregnancy, variables addressed, test uptake, significant factors of decision-making, and methodological quality of the included studies.

To synthesize the data, we performed a qualitative synthesis of findings. We identified a variety of themes involved in the decision-making process about prenatal testing, such as sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, test characteristics, psychological aspects, attitude toward termination of pregnancy, relational factors, knowledge of prenatal testing, and information provision.

Results

Studies selection and characteristics

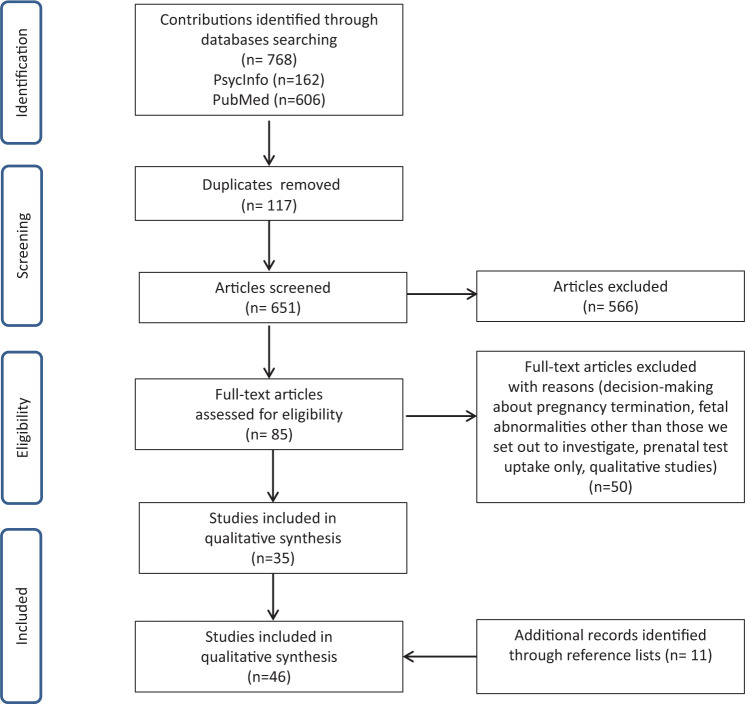

Databases searching identified 768 articles; afterwards duplicates removal pinpointed 651 potentially eligible studies. After reading titles and abstracts, 566 articles were excluded; of the remaining 85, 46 met our inclusion criteria (see Figure 1 for studies selection and Table 1 for a summary of the selected studies).

Figure 1.

Study selection.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Authors, year, country | Participants | Risk’s level of pregnancy | Type of Study | Variables | Test uptake | Significant factors of decision-making | NIH Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grinshpun-Cohen et al., 2015a (ISRAEL) | 42 women | Low risk | Quantitative | - Accurate recall of risk estimates; - Level of risk in NIPT; - Understanding of screening results; - Maternal age; - Family history; - Available public funding. |

46.7% amniocentesis, of which 6.6% <35 years old 86.7% >35 years old |

- All: age, wanting certainty, having performed amniocentesis in a previous pregnancy, recommendation of the doctor. - Only <35 years old: (for not doing amniocentesis) risk of amniocentesis; level of risk obtained in non-invasive screening. |

Fair |

| Fumagalli et al., 2018 (ITALY) | 448 women | Low risk | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Perceived risk and acceptability of having a baby with DS; - Perceived risk and acceptability of experiencing a procedure-related miscarriage. |

55.13% NIPT 9.15% NIPT and IPT 7.58% only IPT 37.27% no test |

- Perceived risk and acceptability: undergoing non-invasive prenatal tests is influenced by the risk of carrying a fetus with DS less acceptable and considering the risk of miscarriage more acceptable. - Undergoing invasive test is influenced only by the acceptability of the 1/200 risk of miscarriage and the 1/350 risk of DS. - Acceptability rather than the numerical likelihood affects the interpretation of a given risk. |

Fair |

| Dahl et al., 2011a (DENMARK) | 4095 women | All risk levels | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Clinical characteristics; - Knowledge. |

// | - Knowledge: women undergoing NT scan had a significantly better knowledge about first-trimester combined DS screening compared with women who did not participate in such examination. | Fair |

| Dahl et al., 2011b (DENMARK) | 4111 women | All risk levels | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Clinical characteristics; - Knowledge of prenatal examinations; - Decisional conflict; - Personal wellbeing; - Worries in pregnancy. |

// | - Knowledge: a higher level of knowledge was associated with less decisional conflict, higher levels of wellbeing and no worries. | Fair |

| Farrell et al., 2011 (USA) | 139 women | All risk levels | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Knowledge of DS; - Knowledge of first trimester screening; - Following diagnostic options; - Understanding of screen results; - Values and beliefs; - Decision-making process. |

// | - Sociodemographic characteristics: non-Caucasian women were more likely to consider a false positive to be a less important decision-making factor. - Knowledge: women’s knowledge of their intentions about the outcome of the pregnancy based on the test results, knowledge of chorionic villus sampling and the risks associated with those procedures. - Values and beliefs about termination and about raising a child with DS. - Test characteristics: the possibility of a false positive result. |

Fair |

| Nazaré et al., 2011 (PORTUGAL) | 112 couples | High risk | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Perception of the Decision-Making process regarding amniocentesis; - Perception of the intimacy level of a dyadic relationship. |

// | - Relational factors: 86% shared the decision regarding amniocentesis with partners; men perceived their partners to have a significantly higher influence on the decision; marital intimacy was related to decision sharing and couple’s agreement; men’s participation in genetic counseling was not associated with acceptance of amniocentesis. | Fair |

| Schoonen et al., 2012 (THE NETHERLANDS) | 510 women, plus data collected by midwives on 6435 pregnancies | All risk levels | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Knowledge; - Attitudes toward the screening; - Intention to participate in prenatal screening; - Decision-making process. |

32.8% willing to participate to NIPT | - Sociodemographic characteristics: older women had a better knowledge of DS. - Knowledge: women taking part in the screening program had a better knowledge of DS and of the screening program. - Attitude: women taking part in the screening program had a better attitude toward prenatal screening. - Religiosity: religious activity was associated with lower levels of knowledge, attitude and intention to participate. |

Poor |

| Bangsgaard and Tabor, 2013 (DENMARK) | 534 women 430 partners |

All risk levels | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Fertility treatment; - Informed choice; - Satisfaction with the decision. |

99.6% cFTS | - Sociodemographic characteristics: informed choice was predicted by woman’s and partners’ education (>for medium and high education). | Good |

| Carroll et al., 2013 (UK) | 65 women 41 partners |

All risk levels | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Screening test attributes that couples place most value on; -Test characteristics. |

// | - Test characteristics: test cost, detection rate and delay in receiving results. | Fair |

| McCoyd, 2013 (USA) | 659 women | All risk levels | Mixed methods | - Preparedness for prenatal diagnosis; - Knowledge about prenatal diagnosis. |

// | - Preparedness: the majority of women never thought anything could be wrong with their fetus and had not discussed with the father or the healthcare workers that possibility. - Knowledge: women did not have a high level of knowledge concerning prenatal screening and diagnosis. |

Poor |

| Verweij et al., 2013 (THE NETHERLANDS) | 147 women | All risk levels | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Attitude toward prenatal screening and toward NIPT. |

54% cFTS 5% IPT 42% no test |

- Psychological factors: obtaining information regarding the baby’s health was the main reason for accepting cFTS, a low perceived risk and unfavorable features of the test were the main reasons for declining. - Attitude toward NIPT: 82% expressed an interest in performing NIPT, 61% were interested in NIPT only as a replacement for invasive procedures or screening; 57% of the women who rejected prenatal screening in the current system would elect to have NIPT if it were available. |

Fair |

| Chan et al., 2014 (CHINA) | 358 women | All risk levels | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Clinical characteristics; - Preference between NIPT and IPT using gamble technique. |

Perspective IF their screening test was positive: 19.6% sure for IPT 10% sure for NIPT 70.4% willing to gamble according to the detection rate of NIPT |

- Sociodemographic characteristics: women with secondary education or below prefer IPT; single women showed a higher acceptable detection rate (99.3%). - Clinical characteristics: women with previous miscarriage prefer NIPT. - NIPT detection rate of 95% for being accepted as an alternative to IPT for 50% of gambling women. |

Fair |

| Dicke et al., 2014 (USA) | 2643 women | All risk levels | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Method of risk reporting (emphasizing a woman’s age-risk for DS and adjusted risk after screening, rather than classifying a result as “positive” or “negative”). |

100% cFTS of which 20.2% did Stepwise Sequential screening following cFTS results. Of the 4.8 % with high-risk, 57.9 % did not have a follow-up, 19.8 % had Stepwise Sequential screening, 23 % had IPT |

- Sociodemographic characteristics: women who declined Stepwise Sequential screening were more likely to be Black and Hispanic and to have lower education level. | Fair |

| Farrell et al., 2014 (USA) | 334 women | All risk levels | Quantitative | - Test characteristics; - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Clinical characteristics; - Attitudes, informational needs, and decision-making process with respect to current and future applications of NIPT. |

42.6% willing to participate to NIPT | - Test characteristics: NIPT’s detection rate, indications, performance. - Sociodemographic characteristics: white women with a college education or more were more likely to require <24 hours to decide whether to have NIPT compared to white women with less education. - Clinical characteristics: high-risk women prioritized information about the chance of a false positive result. |

Poor |

| Lewis et al., 2014 (UK) | 1087 women 18 partners |

All risk levels | Quantitative | - Test characteristics - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Psychosocial factors associated with decision-making process; - Attitude toward NIPT. |

86.7% willing to participate to NIPT | - Test characteristics: the most important factor associated with decision-making was the safety for the baby. - Sociodemographic characteristics: having or knowing someone who has a child with trisomy 21, not having children, non-white ethnicity were associated with NIPT use. - Psychological factors: when evaluating NIPT, 67% of participants would make a decision at the same appointment as counselling. For IPT, 70.8% would want a few days to think about it. NIPT accepters were more likely to “feeling we should use all the medical tests available to us”. |

Fair |

| Gil et al., 2015 (UK) | 6782 women | All risk levels | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Clinical characteristics. |

98.1% cFTS - high-risk group: 40% CVS, 57.3% NIPT, 2.7% no further investigations. - intermediate-risk group: 91.7% NIPT, 8.3% no further investigations. - low-risk group: 100% no further investigations. |

- Sociodemographic characteristics: In the high-risk group, Afro-Caribbean racial origin predicted a negative attitude toward CVS. - In the intermediate-risk group, factors affecting the decision in favor of NIPT testing were university education and increasing maternal age, whereas predictors against testing were being of Afro-Caribbean racial origin and being parous. - Clinical characteristics: In the intermediate-risk group, factors affecting the decision in favor of NIPT testing were increasing risk for trisomies and smoking. - Attitude toward pregnancy termination: In the high-risk and intermediate-risk group, women declined further invasive or non-invasive tests if they did not contemplate pregnancy termination. - Psychological factors: In the intermediate-risk group, the main reasons for declining further prenatal testing were avoiding anxiety of waiting for the results of further tests. |

Fair |

| Silcock et al., 2015 (UK) | 393 health professionals 523 women |

All risk level | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Information provision. |

// | - Sociodemographic characteristics: health professionals’ age, years of experience and religion; women’s relationship status and education. - Information provision: pregnant women were more interested in potential risks involved in the test regardless of test type; strong preference for testing on the same day as pre-test counseling. |

Fair |

| Beulen et al., 2015 (THE NETHERLANDS) | 596 women | All risk levels | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Religious beliefs; - Test characteristics. |

85.1% consider prenatal test as an option | - Sociodemographic characteristics and religiosity: more likely to decline prenatal testing when age ⩽ 35 years, low or intermediate level of education, net monthly household income ⩽ €2999, religious. - Test characteristics: level of information and miscarriage risk. |

Fair |

| Skutilova, 2015 (CZECH REPUBLIC) | 271 women | All risk levels | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Clinical characteristics; - Knowledge and information provision; - Decision-making process; - Feelings over time about IPT. |

// | - Clinical characteristics: there is a significant correlation between previous spontaneous abortion and negative feelings about amniocentesis. - Knowledge and information provision: knowing more information concerning individual tests reassures pregnant women, especially if this information is given by their gynecologist (rather than sought over the internet). - Decision-making process: the main reason for undergoing invasive tests is to make sure the fetus is healthy; the main reason against undergoing invasive tests concerns the risk or the complications associated with the test. |

Poor |

| Ternby et al., 2015 (SWEDEN) | 105 women 104 partners |

All risk levels | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Reasons for undergoing CFTS testing: age ⩾ 35, be sure of baby’s health, ease worries, choice of my partner, previous child with illness. |

100% cFTS | - Reasons for undergoing CFTS testing: be sure of baby’s health, ease worries, age ⩾ 35 | Poor |

| Sahlin et al., 2016 (SWEDEN) | 1003 women | All risk levels | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Attitude toward prenatal examinations; - Attitude toward having a child with a chromosomal abnormality; - Knowledge; - Information provision. |

78.4% ultrasound 66% cFTS 4.6% CVS 3.4% other 2.5% amniocentesis 1% NIPT |

- Attitude toward prenatal examination: positive attitude toward prenatal examinations and NIPT because are risk free procedures; worry about the baby’s health and the urge to have as much information as possible about the fetus. - Information provision: oral information. |

Fair |

| Seven et al., 2016 (TURKEY) | 274 women | All risk levels | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Clinical characteristics; - Reasons for accepting or declining the test; - Knowledge. |

36.1% prenatal screening 2.5% amniocentesis |

- Sociodemographic characteristics: parity, having a child with a genetic disorder, duration of marriage. - Clinical characteristics: history of spontaneous abortion. - Knowledge: insufficient knowledge. |

Fair |

| Ternby et al., 2016 (SWEDEN) | 141 women | All risk levels in IPT group High risk for group declining IPT |

Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Reasons for accept/decline IPT; - Kind of information on IPT received; - Satisfaction regarding information on IPT received. |

53.90% IPT | - Reasons for accepting IPT: ease worries 63.2%; be sure of baby’s health 44.7%; age ⩾ 35 23.7%; screening indicated high risk 13.2%. - Reasons for declining IPT: termination of pregnancy is not an option 58.5%; IPT increases the risk of miscarriage 56.9%; can take care of a child with DS 43.1%; DS is not a serious condition 35.4%; low risk 29.2%; knowing someone with DS 28% |

Fair |

| Chen et al., 2018 (FINLAND) | 28 (qualitative) + 185 women (quantitative) | All risk levels | Mixed method | - Test characteristics - Relational factors - Beliefs and subjective norms; - Perceived behavioral control; - Decisional conflict; - Anxiety. |

78.6% cFTS 6% STS |

- Test characteristics: cFTS better than STS for earlier estimation, higher accuracy. - Relational factors: suggestions from maternity care units, partners. - Perceived behavioral control: women’s activeness in choice making is not very high. |

Fair |

| Lund et al., 2018 (DENMARK) | 315 women 102 partners |

All risk levels | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Fertility treatment; - Test characteristics; - Knowledge. |

80% NIPT | - Fertility treatment: women with high risk at CFTS and who had undergone fertility treatment valued receiving comprehensive genetic information more than risk of miscarriage. - Test characteristics: both women and their partners valued no miscarriage risk more than receiving comprehensive genetic information. - Knowledge: women who were healthcare professionals placed less emphasis on having no risk of miscarriage. |

Fair |

| Miltoft et al., 2018 (DENMARK) | 203 women before cFTS 50 women after cFTS |

All risk levels | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Psychosocial factors impacting decision-making process; - Attitude toward NIPT. |

// | - Psychological factors: having much information as possible. - Attitude toward NIPT: positive attitude in both groups, safety was the most important factor for choosing NIPT. - NIPT acceptors were less likely to terminate an affected pregnancy. |

Good |

| Laberge et al., 2019 (CANADA) | 882 women 395 partners |

All risk levels | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Information provision; - Relational factors; - Social impact of NIPT; - Decision-making process; - Attitude toward pregnancy termination. |

// | - Information provision: being informed by physician, in person and ahead of time. - Relational factors: over 90% involved partner in the decision-making process. - Attitude toward pregnancy termination: time needed to decide about NIPT is correlated only to intention to continue or terminate the pregnancy in case of positive result. |

Fair |

| Grinshpun-Cohen et al., 2015b (ISRAEL) | 42 women | High risk | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Knowledge; - Attitude toward pregnancy termination; - Psychological factors; - Decision-making process. |

100% amniocentesis | - Sociodemographic characteristics: almost half participants considered age as the main reason for undergoing amniocentesis, but only 44% of these women could recall their age-related risk for a baby with DS. - Knowledge: the majority of women did not have the necessary knowledge to make a decision that is informed by risk estimates with regard to amniocentesis. - Attitude toward pregnancy termination: most participants stated that they would consider termination of the pregnancy if the fetus was diagnosed with an intellectual deficit or with a condition associated with severe disabilities and death within the first year of life. - Psychological factors: wanting certainty, fear of DS. |

Fair |

| Grinshpun-Cohen et al., 2015c (USA) | 49 women | High risk | Mixed method | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Attitudes toward risk estimates and pregnancy termination. |

90% DS screening 22% amniocentesis |

- Psychological factors: the most worried women about pregnancy outcome and the least concerned about procedure-related risks were the most likely to undergo amniocentesis. | Fair |

| van Schendel et al., 2015 (NETHERLANDS) | 381 women | All risk levels | Quantitative | - Attitudes toward DS; - Attitudes toward screening. |

51% would (prospectively) accept NIPT | - Attitudes toward DS: 40% - with NIPT, women would think less comprehensively about participation in prenatal screening; 40% - with NIPT, fewer children with Down syndrome would be born; 68% - NIPT as an option for couples who just want to be able to prepare themselves in case of a child with DS. | Fair |

| Crombag et al., 2016 (NETHERLANDS) | 381 women (quantitative) + 46 women (qualitative) | All risk levels | Mixed method | - Test characteristics; - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Attitudes toward DS; - Attitudes toward termination of pregnancy. |

63% for quantitative and 48% for qualitative study had reason for declining cFTS. Within this sample: - 32% for quantitative and 18% for qualitative study would accept NIPT - 39% for quantitative and 64% for qualitative study would decline NIPT - 29% for quantitative and 18% for qualitative study unsure about NIPT |

- Sociodemographic characteristics: women who reported reasons for declining cFTS were mainly Dutch (92% for quantitative and 91% for qualitative study) and highly educated (52% for quantitative and 77% for qualitative study). - Test characteristics: cFTS gives only a risk estimation’ was the most frequently mentioned reason (55%) for declining. Women who decline cFTS for test-related reasons more often intended to accept cfDNA testing. - Attitudes toward DS and pregnancy termination: women who declined cFTS because of attitudes toward DS and termination of pregnancy more often intended to decline cfDNA testing as well. |

Poor |

| Lewis et al., 2016 (UK) | 582 women (Time1: at the time of NIPT testing) 263 women (Time2: one month following receipt of results) |

All risk levels | Mixed methods | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Clinical characteristics; - Decisional conflict and regret; - Anxiety; - Reasons for accepting or declining NIPT. |

// | - Psychological factors: reassurance was the main motivator for accepting NIPT, particularly amongst medium risk women, with high risk women inclined to accept NIPT to inform decisions around invasive testing. - Test characteristics: safety was the most important factor in the decision to accept NIPT, particularly amongst high risk women. |

Fair |

| van Schendel et al., 2016 (THE NETHERLANDS) | 1091 women | High risk | Quantitative | - Test characteristics; - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Attitude toward the uncertainty of NIPT and the miscarriage risk of IPT; - Attitude toward pregnancy termination; - Informed choice; - Decisional conflict; - Anxiety; - Health literacy. |

96.5% NIPT 3.4% IPT 0.1% no test |

- Test characteristics: safety, accuracy. - Attitude toward pregnancy termination is higher among women who had IPT. - Knowledge: most women choosing IPT made a value-consistent decision. |

Fair |

| Chen et al., 2017 (FINLAND) | 254 women | High risk | Mixed method | - Test characteristics; - Values; - Behavioral beliefs; - Subjective norms; - Perceived choice control. |

73.2% NIPT 15.4% CVS 11.4% amniocentesis |

- Test characteristics: easiness, rapidness, physical comfort, timing, safety of NIPT, accuracy of IPT. - Psychological factors: NIPT if they want to keep the baby and safely obtain information. |

Fair |

| Lo et al., 2017 (CHINA) | 262 women | High risk | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Knowledge; - Informed choice/decision. |

90.5% NIPT 9.5% IPT |

- Knowledge: value-inconsistency is prevalent among NIPT decliners, leading to a much higher rate of uninformed choice than in NIPT acceptors. | Fair |

| Lo et al., 2019 (CHINA) | 262 women | All risk levels | Quantitative | - Decisional conflict and regret; - Anxiety. |

79.01% NIPT 9.16% IPT |

- Knowledge: insufficient knowledge about NIPT was associated with elevated anxiety and with decisional regret. | Fair |

| Watanabe et al., 2017 (JAPAN) | 141 couples | High risk | Quantitative | - Relational factors: differences between pregnant women and their partner in regard to information sources, feelings; relationships with others; - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Decision-making process. |

85.9% NIPT 6.3% amniocentesis or maternal serum screening 7.8% no test |

- Relational factors: partners perceived a passive role in the decision-making process; pregnant woman (more than partners) consulted for NIPT choice family and friends. - Sociodemographic characteristics: advanced maternal age was the most common reason for seeking NIPT. |

Good |

| Canh Chuong et al., 2018 (VIETNAM) | 481 women | High risk | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Knowledge of and attitude toward prenatal examinations. |

72.9% amniocentesis | - Sociodemographic characteristics: higher educational attainment and higher income level are associated to higher amniocentesis uptake; having a baby with congenital defects. - Knowledge and attitude: women with better knowledge and/or attitude about amniocentesis were more likely to accept the test. |

Fair |

| Cheng et al., 2018 (CHINA) | 84 women | High risk | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Clinical characteristics; - Anxiety and depression levels; - Pregnancy stress. |

44.05% IPT 55.95% NIPT |

- Sociodemographic characteristics: women choosing NIPT had a higher educational background than those choosing amniocentesis. - Psychological factors: predictor for IPT was anxiety. |

Fair |

| Schlaikjær-Hartwig et al., 2018 (DENMARK) | 339 women | High risk | Quantitative | - Decisional conflict; - Timing of genetic counselling; - Satisfaction for genetic counselling +after knowing results; - Regret; - Risk taking; - Personality. |

75.4% IPT 23.8% NIPT 0.4% IPT and NIPT 0.4% no test |

- Psychological factors: choosing NIPT was associated with a high decisional conflict; decisional conflict increased when receiving genetic counselling the same day; decisional conflict decreased when satisfaction with the genetic counselling was higher and in association with the personality trait “alexithymia”. | Good |

| Salema et al., 2018 (CANADA) | 11 women | High risk | Mixed method | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Decision-making process; - Satisfaction with decision-making process. |

18.18% NIPT 27.27% amniocentesis 54.54% no test |

- Psychological factors: emotionally and mentally unprepared to receive a high-risk prenatal screening result, the burden of responsibility to “do the right thing”. | Fair |

| Birko et al., 2019 (CANADA) | 882 women, 395 partners and 184 healthcare professionals | All risks levels | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Knowledge about DS and NIPT; - Involvement of others in decision-making; - Future uses of NIPT |

// | - Test characteristics: women and partners thought that their decision to test would be impacted by NIPT being accessible and free of charge; a majority of healthcare professionals thought that only high-risk pregnancies should be eligible for funding. - Healthcare professionals offer NIPT as second-tier screening; strong preference of women and partners for its use as a first-tier screen. - Attitude toward pregnancy termination: 52.9% of pregnant women and 56.7% of their partners reported being interested in knowing whether their fetus has DS in order to “consider terminating the pregnancy if the baby was diagnosed with DS”. |

Poor |

| Cheng et al., 2019 (CHINA) | 84 women | High risk | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Psychological factors; - Pregnancy stress. |

44.05% IPT 55.95% NIPT |

- Sociodemographic characteristics: IPT associated to lower educational background. - Psychological factors: higher anxiety and depression. - IPT choice predicted by anxiety and by the stress due to changes of fetal shape and motility. |

Fair |

| Seror et al., 2019 (FRANCE) | 2436 women | High risk | Quantitative | - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Understanding of CFTS results; - Test characteristics: attitudes toward the trade-off between risk taking and extent of information seeking. |

Preference: 21.1% IPT 75.7% NIPT |

- Test characteristics: aversion to risk of fetal loss related to IPT and aversion to ambiguity generated by incomplete information from NIPT. | Fair |

| van der Steen et al., 2019 (THE NETHERLANDS) | 181 women and 5 clinicians | High risk | Mixed method | Clinicians: - Level of Information-centeredness, patient-centeredness, non-directivity of clinicians. Women: - Sociodemographic characteristics; - Impression of the clinician’s preference; - Information provision; - Anxiety. |

82% NIPT 18% IPT |

- Information provision: clinicians’ style of pre-test counseling. | Fair |

| Ngan et al., 2020 (CHINA) | 274 parents and 141 clinicians (quantitative) + 26 parents and 10 clinicians (qualitative) | All risk levels | Mixed method | - Attitudes toward prenatal testing; - Attitudes toward reproductive autonomy; - Attitudes toward termination of pregnancy; - Attitudes toward raising a child with disability. |

100% prenatal testing | - Attitudes toward termination of pregnancy: Accepting termination of pregnancy in parents and offering it in clinicians was positively associated with attitudes toward prenatal testing and reproductive autonomy. - Relational factors: Parents felt obliged to undertake prenatal testing because of a sense of responsibility irrespective of different cultures. |

Fair |

NIPT: Non-Invasive Prenatal Test; IPT: Invasive Prenatal Test; cFTS: combined First Trimester Screening; CVS: Chorionic Villus Sampling; DS: Down Syndrome; OSCAR: One Stop Clinic for Assessment of Risk test; NHS screening: National Health Service screening; NT: nuchal translucency; STS: serum triple screening test.

NHS screening: measures two blood markers and provide a detection rate of approximately 60%.

OSCAR test: measures two blood markers and incorporates ultrasound techniques with a detection rate of approximately 90%.

Among the selected studies, two examined pregnant women with a low-risk of carrying a fetus with abnormalities, 14 examined women with a high-risk pregnancy and 30 considered pregnant women at all risk levels.

The studies were conducted in the United States (n = 5), Canada (n = 3), United Kingdom (n = 5), The Netherlands (n = 7), Denmark (n = 6), Sweden (n = 3), Finland (n = 2), Czech Republic (n = 1), France (n = 1), Italy (n = 1), Portugal (n = 1), China (n = 6), Japan (n = 1), Israel (n = 2), Turkey (n = 1), and Vietnam (n = 1).

Eight studies were related to prenatal screening, six studies focused on invasive testing, eight studies investigated NIPT, and 24 studies analyzed different kinds of tests.

Seven studies had poor methodological rigor, 35 studies had fair methodological quality, and four studies had good quality.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

The present review identifies advanced maternal age as the principal reason for undergoing prenatal testing (Gil et al., 2015; Schoonen et al., 2012; Ternby et al., 2015), concerning both NIPT (Watanabe et al., 2017) and invasive testing (Grinshpun-Cohen et al., 2015a, 2015b).

Higher educational attainment is associated with a greater use of both invasive and non-invasive prenatal testing (Bangsgaard and Tabor, 2013; Beulen et al., 2015; Canh Chuong et al., 2018; Dicke et al., 2014; Farrell et al., 2014; Gil et al., 2015). In addition, the studies by Chan et al. (2014) and by Cheng et al. (2018) indicate that a low level of education is associated with the choice of invasive prenatal diagnosis rather than NIPT. Only the study by Crombag et al. (2016) reports that Dutch women with a high level of education are more likely to decline cFTS.

As far as the relationship status is concerned, having other children and long-term marital relationship seems to favor prenatal testing uptake independently from invasive or non-invasive test (Lewis et al., 2014; Seven et al., 2017). In contrast, Gil et al. (2015) show that being parous predicts a reduced likelihood of prenatal testing.

Data regarding the association between ethnicity and the use of prenatal testing are scarce and heterogeneous. In particular, some studies report that non-Caucasian women seem to underestimate the importance of a false positive result in their choice (Farrell et al., 2011) and they use NIPT more frequently (Lewis et al., 2014); others show that being non-Caucasian is associated with a negative attitude toward both invasive and non-invasive prenatal tests (Dicke et al., 2014; Gil et al., 2015).

Regarding clinical characteristics, the presence of previous abortion is associated with prenatal screening uptake, with a preference for non-invasive tests such as cFTS and NIPT (Chan et al., 2014; Seven et al., 2017; Skutilova, 2015). Moreover, couples at high risk for cFTS and who have undergone fertility treatment seem to prefer an invasive test that provides certain genetic information and they are willing to face the risk of miscarriage compared to low-risk couples with spontaneous pregnancy (Lund et al., 2018). Similarly, women with a high risk of carrying a baby with chromosomal abnormalities are more likely to undergo prenatal testing and to prioritize information about the chance of a false positive result (Farrell et al., 2014).

Test characteristics

In the decision-making process, women confer a great importance to the technical features of the test, in particular accuracy, safety, timing and easiness (Beulen et al., 2015; Carroll et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2017, 2018; Farrell et al., 2014, Lewis et al., 2014, 2016; Lund et al., 2018; Seror et al., 2019; Skutilova, 2015; van Schendel et al., 2016).

Some studies show that the most important factors for choosing NIPT are its high detection rate and the absence of physical risks for the fetus, along with the easiness of the procedure, especially for high-risk women (Chen et al., 2017; Lewis et al., 2016).

However, some couples do not choose this test or cFTS because they do not provide certainties and generate ambiguity (Crombag et al., 2016; Seror et al., 2019), differently from invasive tests.

Furthermore, some studies highlight costs as a factor affecting NIPT choice, which is quite expensive in many countries (Birko et al., 2019; Carroll et al., 2013).

Finally, the gestational age at which the test can be performed is another relevant factor (Chen et al., 2017, 2018).

Psychological factors

Women choose to undergo prenatal testing in order to seek a good life for themselves and their children, in spite of possible detrimental effects on pregnancy (Cheng et al., 2018, 2019; Grinshpun-Cohen et al., 2015a, 2015c; Lewis et al., 2016; Miltoft et al., 2018; Ternby et al., 2015, 2016; Verweij et al., 2013). In particular, Cheng et al. (2018) report that anxiety is a predictor of invasive prenatal tests uptake. On the contrary, avoiding the anxiety caused by waiting for the result could be a reason to refuse invasive investigations following the screening test (Gil et al., 2015). Fumagalli et al. (2018) investigate women’s decision to undergo prenatal testing depending on the perception of the probability of having a baby with Down Syndrome and the acceptability of this risk and the procedure-related miscarriage. They report that the acceptability of the risk, rather than the numerical likelihood, affects the interpretation of the result.

Moreover, personality seems to play a role in decision-making, as women with alexithymic traits show less decisional conflict when choosing NIPT (Schlaikjær-Hartwing et al., 2019).

Attitude toward termination of pregnancy

In general, women undergoing prenatal testing seem more inclined to terminate pregnancy in the event of an abnormal outcome compared to women who decline prenatal testing (Birko et al., 2019; Crombag et al., 2016; Farrell et al., 2011; Gil et al., 2015; Miltoft et al., 2018). Even more clearly, women who consider terminating pregnancy in the event of a positive outcome choose more frequently invasive tests, consequently accepting the risk of a possible miscarriage related to the procedure (Grinshpun-Cohen et al., 2015a, 2015c; Ternby et al., 2016; van Schendel et al., 2016).

Women undergoing prenatal screening to prepare themselves for the birth of a child with Down Syndrome take more time to decide about going through NIPT (Laberge et al., 2019; van Schendel et al., 2015).

Relational factors

Prenatal testing does not involve only the pregnant woman, but also her partner, family and society.

In particular, some studies report that decision-making about screening for Down Syndrome is a couple joint decision, with little involvement from other people (Laberge et al., 2019; Nazaré et al., 2011), even though pregnant women want to retain control over the screening outcome. In fact, partners may perceive a more passive role in decision-making (Nazaré et al., 2011; Watanabe et al., 2017).

Other studies highlight that pregnant women experience social influence from maternity care units and from their partners (Chen et al., 2018), and they seem to consult with family and friends for the NIPT choice more often than their partners do (Watanabe et al., 2017).

Furthermore, women feel a sort of social pressure in so far as they consider the risk assessment compulsory and they perceive the responsibility of doing the right thing (Ngan et al., 2020; Salema et al., 2018).

Finally, religion may influence decision-making, as Islam seems to be associated with very low prenatal testing uptake (Seven et al., 2017).

Knowledge

Knowledge of the characteristics of the different prenatal test options and knowledge of the genetic conditions tested are essential for informed decision-making. Most studies investigating the level of prenatal screening knowledge show that women participating in this program have a better knowledge of Down Syndrome and of the screening program itself, compared to women who decline such possibility (Dahl et al., 2011a, 2011b; Lo et al., 2019; Schoonen et al., 2012). Farrell et al. (2011) report a similar finding concerning CVS. In particular, it seems that a higher level of knowledge is associated with less decisional conflict and decisional regret, higher levels of wellbeing and lower levels of anxiety (Dahl et al., 2011b; Lo et al., 2019).

However, studies from different countries affirm that, in general, women do not have enough knowledge to be able to make an informed decision concerning prenatal screening and diagnosis (Grinshpun-Cohen et al., 2015a; McCoyd, 2013; Seven et al., 2017).

Information provision

Some studies underline the importance for women of receiving information about prenatal testing options in person rather than through information brochures and as early as possible during pregnancy (Laberge et al., 2019; Sahlin et al., 2016). Regarding the type of information provided, pregnant women are more interested in the potential risks involved in the test regardless of test type (Lewis et al., 2014). Only two studies consider the role of the informant, identifying the physician as women's preferred information provider (Laberge et al., 2019), especially the gynecologist (Skutilova, 2015).

Pre-test counseling characterized by clinicians’ patient-centeredness communication and non-directiveness, has been found to influence the test uptake (van der Steen et al., 2019). For example, talking about the risk of miscarriage for an invasive procedure using words like “negligible” or “extremely small” encourages taking this test.

Silcock et al. (2015) show that women prefer to take the test on the same day as counseling, in particular NIPT (Silcock et al., 2015). In contrast, Schlaikjær-Hartwig et al. (2019) report an increase in decisional conflict the day of genetic counseling. According to Lewis et al. (2014), the decision about the invasive test takes several days to be elaborated.

Discussion

The aim of this review was to explore the significant factors involved in prenatal testing decision-making and, in particular, whether there were differences according to the type of test chosen.

The decision-making process in the field of prenatal testing appears to be complex and composed of different levels. First, variables relevant to the decision include individual aspects, such as demographic and clinical characteristics, along with the needs and emotions of the woman or the couple (e.g. anxiety). In addition, contextual factors related to the type, quantity and modality of information received may contribute to a clear understanding of the technical features of the test, allowing for a better informed choice. Moreover, relational factors seem to play a significant role in decision-making, in fact marital intimacy is related to sharing decisions and most women share the choice of prenatal testing with their partner. Couples make a decision by balancing multiple dimensions, which are strictly interrelated. The studies examined show that non-invasive prenatal screening is the most chosen procedure when the sample includes women with low risk pregnancy or both low and high-risk pregnancy (Bangsgaard and Tabor, 2013; Chan et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2018; Dahl et al., 2011a, 2011b; Farrell et al., 2014; Fumagalli et al., 2018; Gil et al., 2015; Lo et al., 2019; Lund et al., 2018; Miltoft et al., 2018; Sahlin et al., 2016; Seven et al., 2017; van Schendel et al., 2015; Verweij et al., 2013). In studies with samples composed only of high-risk women, this trend is confirmed in favor of NIPT compared to invasive diagnosis (Cheng et al., 2018, 2019; Lo et al., 2017; Schlaikjær-Hartwing et al., 2019; Seror et al., 2019; van der Steen et al., 2019; van Schendel et al., 2016; Watanabe et al., 2017). The couples’ preference for the use of the NIPT as a first-tier screen therefore clearly emerges. In addition, women who rejected the available prenatal screening procedures would elect to have NIPT if it were available (Birko et al., 2019; Verweij et al., 2013). This data is in line with existing literature which stresses the importance of introducing NIPT and its relevance in reducing invasive procedures (Scott et al., 2018).

From a socio-demographic and clinical-obstetric point of view, studies with different quality levels unanimously indicate that advanced maternal age (Beulen et al., 2015; Gil et al., 2015; Grinshpun-Cohen et al., 2015a, 2015b; Schoonen et al., 2012; Ternby et al., 2015; Watanabe et al., 2017), having a risk for genetic anomalies and previous abortions induce women to undergo prenatal testing, without distinction between invasive or non-invasive test (Chan et al., 2014; Seven et al., 2017; Skutilova, 2015). Similarly, no differences emerge in the use of both invasive and non-invasive prenatal testing in relation to educational level, in particular a higher educational attainment is associated with a greater use of prenatal test in general (Bangsgaard and Tabor, 2013; Beulen et al., 2015; Canh Chuong et al., 2018; Dicke et al., 2014; Farrell et al., 2014; Gil et al., 2015). Only a study with poor methodological quality (Crombag et al., 2016) reports that women with a high level of education are more likely to decline cFTS.

In a homogeneous and univocal way, the studies show that women confer a great importance to the technical features of the test, in particular accuracy, safety, timing and easiness, often favoring the recent NIPT (Beulen et al., 2015; Carroll et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2017, 2018; Farrell et al., 2014; Lewis et al., 2014, 2016; Lund et al., 2018; Seror et al., 2019; Skutilova, 2015; van Schendel et al., 2016).

Another parameter on which NIPT is positively considered is the gestational age at which it can be performed (Chen et al., 2017, 2018). In fact, the NIPT can be carried out from the 9th gestational week, leaving women who get a positive result several weeks to make a decision concerning possible pregnancy termination within the terms of the law (Scott et al., 2018). In contrast, the amniocentesis is performed starting from the 15th week, leading to a more complicated procedure for pregnancy termination, which is associated with more adverse psychological and physical implications (Alfirevic et al., 2017). Notably, these patterns clearly emerge, irrespectively from the quality of the studies.

The psychological factors that influence decision-making in prenatal testing area involve a need to have as much information as possible about the fetus and intolerance to uncertainty. Both aspects are related to the desire of gaining control over pregnancy and lower anxiety levels. In line with the existing literature (Ahmed et al., 2006a, 2006b), our review shows that most women consider to undergo prenatal testing in order to know whether the fetus is healthy and to be reassured (Cheng et al., 2018, 2019; Grinshpun-Cohen et al., 2015a, 2015c; Lewis et al., 2016; Miltoft et al., 2018; Ternby et al., 2015, 2016; Verweij et al., 2013). It is conceivable that such knowledge is associated with the desire to eliminate uncertainty about the health status of the fetus.

The attitude toward abortion in case of genetic abnormalities of the fetus plays a crucial role in the choice of whether or not undergoing prenatal testing. In particular, the results show that women who are more more likely to have abortion are also more likely to undergo prenatal testing (Birko et al., 2019; Crombag et al., 2016; Farrell et al., 2011; Gil et al., 2015; Miltoft et al., 2018) and they also accept the risk of miscarriage foreseen by invasive procedures (Grinshpun-Cohen et al., 2015a, 2015c; Ternby et al., 2016; van Schendel et al., 2016). However, the percentage of couples who undergo prenatal testing to prepare themselves to welcome a disabled child should not be overlooked.

Unfortunately, the papers included in our review do not report data on the influence of cultural factors and it would be interesting to learn more since the existing literature (van den Heuvel and Marteau, 2008; van den Heuvel et al., 2009) shows that in Northern Europe greater value is placed on the importance of parental choice in prenatal testing than in Southern Europe or Asia, where the point of view of significant others and healthcare professionals is deemed more important in the test decision. Responsibility for the care of children with disabilities seems to put a heavy burden on Asian families and communities. This burden can be reflected in cultural differences in attitudes toward disability, which tend to be more negative in Asian countries where many consider the birth of a disabled child irresponsible toward both family and society (van den Heuvel et al., 2009). In addition, having a faith that strongly condemns abortion, such as Islam, as well as living in countries where abortion is illegal, strongly influence women’s choice not to undergo prenatal testing of any kind (Seven et al., 2017). Religion also seems to be associated with the level of knowledge; in fact, those who describe themselves as religious also report a low level of knowledge and consequently undergo less likely prenatal testing (Beulen et al., 2015; Schoonen et al., 2012; Seven et al., 2017). On the contrary, good knowledge correlates with a greater uptake of prenatal testing (Dahl et al., 2011a, 2011b; Farrell et al., 2011; Schoonen et al., 2012).

Pregnancy is an important event not only in the life of women, but also in the life of their partner. As several studies have shown, the choice of prenatal testing involves the couple and rarely external elements (Laberge et al., 2019; Nazaré et al., 2011). However, the social pressure felt by women, who often interpret prenatal testing as part of pregnancy routine without a real conscious choice, should not be underestimated (Ngan et al., 2020; Salema et al., 2018).

Regarding prenatal test counseling, the results indicate a preference for oral and specific information on the risks of each type of test, provided by the physician (Laberge et al., 2019; Lewis et al., 2014; Sahlin et al., 2016; Skutilova, 2015).

In general, we suggest caution in reading the data of low-quality studies. In turn, a greater emphasis should be placed on studies conducted with good methodological rigor, which show that women with higher education make more informed choices (Bangsgaard and Tabor, 2013) and that women value receiving as much information as possible (Miltoft et al., 2018). Moreover, decisional conflict increases when women receive genetic counselling the same day as NIPT, but it can be reduced if women are satisfied with the genetic counselling or if they present certain personality traits (Schlaikjær-Hartwig et al., 2018). Another important factor for pregnant women is the safety of the test, especially for those who are less likely to terminate an affected pregnancy (Miltoft et al., 2018). Finally, high-quality studies suggest that advanced maternal age is the most common reason for seeking NIPT (Watanabe et al., 2017).

Conclusion

This is the first review that examines the decision-making process involved in the choice of prenatal testing, including the NIPT as a possible choice. Although our review provides some insights, some limitations should be noted. First, the inclusion of studies run in countries with different health policies and health-related values leads to a complex pattern of results, highlighting the interaction of these elements with individual factors. In light of these considerations, future studies could specifically investigate the weight of individual factors in different cultural contexts. Another limitation is the over-representation of North-European countries, with few studies conducted in Southern Europe. Indeed, the sole inclusion of studies published in English may have narrowed the results, future reviews should thus include studies published in other languages to cover national peer-reviewed literature.

Other considerations emerge from this review. Currently, only one longitudinal study is available. Longitudinal studies are important to understand the trajectory of emotional difficulties in this population and to investigate the psychological consequences of the choice made.

Most of the studies examined use non-validated tools, created ad hoc for the study, for the evaluation of the decision-making process, which do not allow a precise review of the results, limiting the possibility of drawing strong conclusions. In fact, the qualitative evaluation of the studies shows that only four of them have a good methodological rigor, as the tools or methods used for measuring outcomes are not accurate and reliable. This aspect is important because it influences confidence in the validity of study results. Interestingly, three out of four high-quality studies are Danish, which could bias the results. However, despite different quality levels, the majority of the studies included in the present review point toward the same direction. Nonetheless, given that overall the quality of studies is not particularly high, we must underline how this branch of medicine and health psychology would benefit from studies conducted with greater methodological rigor.

The interaction between the characteristics of women and healthcare professionals has not been deeply explored in this review. Moreover, more research is needed on the influence of healthcare providers and also of the healthcare system characteristics.

The present review shows the importance of an individualized, oral counseling to couples, taking into account individual factors (i.e. the woman’s age and her clinical history), and clearly explaining the technical features of the test. It would also be recommended to check with targeted questions if the woman/couple understood the main features of the test. For example, the model proposed by Gammon et al. (2018) seems to increase the knowledge about available prenatal tests, the test uptake, and facilitate decision-making. In this model, patients receive information on testing options in a group session and a one-to-one interview for individual questions and risk assessment is subsequently carried out (Gammon et al., 2018). In conclusion, the present review could help healthcare systems to pinpoint which information is relevant to women evaluating prenatal testing and how this information should be provided. Moreover, our findings could help gynecologists to identify which women would benefit psychological counseling.

Appendix 1

Search strategy

Search: PubMed; PsycINFO.

Search 1 (prenatal test);

“prenatal screening”; “prenatal diagnosis”; “prenatal genetic testing”; “invasive prenatal testing”; “non invasive prenatal testing”; “amniocentesis”; “cell free fetal DNA”; “chorion villus”.

=COMBINE WITH OR

Search 2 (decision making process);

“decision making.”

Combine Search 1 AND Search 2.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Federica Ferrari  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4740-2704

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4740-2704

References

- Ahmed S, Atkin K, Hewison J, et al. (2006. a) The influence of faith and religion and the role of religious and community leaders in prenatal decisions for sickle cell disorders and thalassaemia major. Prenatal Diagnosis 26(9): 801–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S, Green JM, Hewison J. (2006. b) Attitudes toward prenatal diagnosis and termination of pregnancy for thalassaemia in pregnant Pakistani women in the North of England. Prenatal Diagnosis 26(3): 248–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akolekar R, Beta J, Picciarelli G, et al. (2015) Procedure-related risk of miscarriage following amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 45(1): 16–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfirevic Z, Navaratnam K, Mujezinovic F. (2017) Amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling for prenatal diagnosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Review 9(9): CD003252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangsgaard L, Tabor A. (2013) Do pregnant women and their partners make an informed choice about first trimester risk assessment for Down syndrome, and are they satisfied with the choice? Prenatal Diagnosis 33(2): 146–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beulen L, Grutters JPC, Faas BHW, et al. (2015) Women’s and healthcare professionals’ preferences for prenatal testing: A discrete choice experiment. Prenatal Diagnosis 35(6): 549–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birko S, Ravitsky V, Dupras C, et al. (2019) The value of non-invasive prenatal testing: Preferences of Canadian pregnant women, their partners, and health professionals regarding NIPT use and access. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 19(1): 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canh Chuong N, Minh Duc D, Anh ND, et al. (2018) Amniocentesis test uptake for congenital defects: Decision of pregnant women in Vietnam. Health Care for Women International 39(4): 493–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll FE, Al-Janabi H, Flynn T, et al. (2013) Women and their partners’ preferences for Down’s syndrome screening tests: A discrete choice experiment. Prenatal Diagnosis 33(5): 449–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan YM, Leung TY, Chan OKC, et al. (2014) Patient’s choice between a non-invasive prenatal test and invasive prenatal diagnosis based on test accuracy. Fetal Diagnosis and Therapy 35(3): 193–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, Tenhunen H, Torkki P, et al. (2017) Considering medical risk information and communicating values: A mixed-method study of women’s choice in prenatal testing. PLoS One 12(3): 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, Tenhunen H, Torkki P, et al. (2018) Facilitating autonomous, confident and satisfying choices: A mixed-method study of women’s choice-making in prenatal screening for common aneuploidies. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 18(1): 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng BH, Chen JH, Wang GH. (2019) Psychological factors influencing choice of prenatal diagnosis in Chinese multiparous women with advanced maternal age. Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 32(14): 2295–2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombag NM, Bensing JM, Iedema-Kuiper R, et al. (2013) Determinants affecting pregnant women’s utilization of prenatal screening for Down syndrome: a review of the literature. Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 26(17): 1676–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombag NM, Vellinga YE, Kluijfhout SA, et al. (2014) Explaining variation in Down’s syndrome screening uptake: Comparing the Netherlands with England and Denmark using documentary analysis and expert stakeholder interviews. BMC Health Service Resource 14(1): 437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombag NMTH, Boeije H, Iedema-Kuiper R, et al. (2016) Reasons for accepting or declining Down syndrome screening in Dutch prospective mothers within the context of national policy and healthcare system characteristics: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 16(1): 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl K, Hvidman L, Jørgensen FS, et al. (2011. a) Knowledge of prenatal screening and psychological management of test decisions. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 38(2): 152–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl K, Hvidman L, Jørgensen FS, et al. (2011. b) First-trimester down syndrome screening: Pregnant women’s knowledge. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 38(2): 145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dicke JM, Van Duyne L, Bradshaw R. (2014) The utilization and choices of aneuploidy screening in a midwestern population. Journal of Genetic Counseling 23(5): 874–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell RM, Agatisa PK, Nutter B. (2014) What women want: Lead considerations for current and future applications of noninvasive prenatal testing in prenatal care. Birth 41(3): 276–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell RM, Nutter B, Agatisa PK. (2011) Meeting patients’ education and decision-making needs for first trimester prenatal aneuploidy screening. Prenatal Diagnosis 31(13): 1222–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli S, Antolini L, Nespoli A, et al. (2018) Prenatal diagnosis tests and women’s risk perception: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology 39(1): 73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammon BL, Otto L, Wick M, et al. (2018) Implementing group prenatal counseling for expanded noninvasive screening options. Journal of Genetic Counseling 27(4): 894–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil MM, Giunta G, Macalli EA, et al. (2015) UK NHS pilot study on cell-free DNA testing in screening for fetal trisomies: Factors affecting uptake. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 45(1): 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godino L, Turchetti D, Skirton H. (2013) A systematic review of factors influencing uptake of invasive fetal genetic testing by pregnant women of advanced maternal age. Midwifery 29(11): 1235–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JM, Hewison J, Bekker HL, et al. (2004) Psychosocial aspects of genetic screening of pregnant women and newborns: A systematic review. Health Technology Assessment 8(33): iii, ix–x, 1–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinshpun-Cohen J, Miron-Shatz T, Berkenstet M, et al. (2015. a) The limited effect of information on Israeli pregnant women at advanced maternal age who decide to undergo amniocentesis. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research 4(1): 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinshpun-Cohen J, Miron-Shatz T, Rhee-Morris L, et al. (2015. b) A priori attitudes predict amniocentesis uptake in women of advanced maternal age: A pilot study. Journal of Health Communication 20(9): 1107–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinshpun-Cohen J, Miron-Shatz T, Ries-Levavi L, et al. (2015. c) Factors that affect the decision to undergo amniocentesis in women with normal Down syndrome screening results: It is all about the age. Health Expectation 18(6): 2306–2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laberge AM, Birko S, Lemoine MÈ, et al. (2019) Canadian pregnant women’s preferences regarding NIPT for Down syndrome: The information they want, how they want to get it, and with whom they want to discuss it. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada 41(6): 782–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiva Portocarrero ME, Garvelink MM, Becerra Perez MM, et al. (2015) Decision AIDS that support decisions about prenatal testing for Down syndrome: An environmental scan. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 15(1): 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C, Hill M, Chitty LS. (2016) A qualitative study looking at informed choice in the context of non-invasive prenatal testing for aneuploidy. Prenatal Diagnosis 36(9): 875–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C, Hill M, Silcock C, et al. (2014) Non-invasive prenatal testing for trisomy 21: A cross-sectional survey of service users’ views and likely uptake. BJOG An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 121(5): 582–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobel M, Dias L, Meyer BA. (2005) Distress associated with prenatal screening for fetal abnormality. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 28(1): 65–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo DYM, Corbetta N, Chamberlain PF, et al. (1997) Presence of fetal DNA in maternal plasma and serum. Lancet 350(9076): 485–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo TK, Chan KY-K, Kan AS-Y, et al. (2017) Informed choice and decision making in women offered cell-free DNA prenatal genetic screening. Prenatal Diagnosis 37(3): 299–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo TK, Chan KY-K, Kan AS-Y, et al. (2019) Decision outcomes in women offered noninvasive prenatal test (NIPT) for positive Down screening results. Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 32(2): 348–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund ICB, Becher N, Petersen OB, et al. (2018) Preferences for prenatal testing among pregnant women, partners and health professionals. Danish Medical Journal 65(5): 1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoyd JLM. (2013) Preparation for prenatal decision-making: A baseline of knowledge and reflection in women participating in prenatal screening. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology 34(1): 3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe SA. (2018) Genetic counselling, patient education, and informed decision-making in the genomic era. Seminars in Fetal & Neonatal Medicine 23(2): 142–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miltoft CB, Rode L, Tabor A. (2018) Positive view and increased likely uptake of follow-up testing with analysis of cell-free fetal DNA as alternative to invasive testing among Danish pregnant women. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 97(5): 577–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health (2014) Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies. Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed 15 June 2020).

- Nazaré B, Fonseca A, Gameiro S. (2011) Amniocentesis due to advanced maternal age: The role of marital intimacy in couples’ decision-making process. Contemporary Family Therapy 33(2): 128–142. [Google Scholar]

- Ngan OMY, Yi H, Bryant L, et al. (2020) Parental expectations of raising a child with disability in decision-making for prenatal testing and termination of pregnancy: A mixed methods study. Patient Education and Counseling. Epub ahead of print 13 May 2020. DOI: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öhman SG, Grunewald C, Waldenström U. (2003) Women's worries during pregnancy: Testing the Cambridge Worry Scale on 200 Swedish women. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 17(2): 148–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahlin E, Nordenskjöld M, Gustavsson P, et al. (2016) Positive attitudes towards non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) in a Swedish cohort of 1,003 pregnant women. PLoS One 11(5): 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salema D, Townsend A, Austin J. (2018) Patient decision-making and the role of the prenatal genetic counselor: An exploratory study. Journal of Genetic Counseling 28(1): 155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapp JC, Hull SC, Duffer S, et al. (2010) Ambivalence toward undergoing invasive prenatal testing: An exploration of its origins. Prenatal Diagnosis 30(1): 77–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaikjær-Hartwig TS, Borregaard Miltoft C, Malmgren CI, et al. (2019) High risk—What’s next? A survey study on decisional conflict, regret, and satisfaction among high-risk pregnant women making choices about further prenatal testing for fetal aneuploidy. Prenatal Diagnosis 39(8): 635–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoonen M, Wildschut H, Essink-Bot ML, et al. (2012) The provision of information and informed decision-making on prenatal screening for Down syndrome: a questionnaire- and register-based survey in a non-selected population. Patient Education and Counseling 87(3): 351–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott FP, Menezes M, Palma-Dias R, et al. (2018) Factors affecting cell-free DNA fetal fraction and the consequences for test accuracy. Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine 31(14): 1865–1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seror V, L’Haridon O, Bussières L, et al. (2019) Women’s attitudes toward invasive and noninvasive testing when facing a high risk of fetal Down syndrome. JAMA Network Open 2(3): e191062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seven M, Akyüz A, Eroglu K, et al. (2017) Women’s knowledge and use of prenatal screening tests. Journal of Clinical Nursing 26(13–14): 1869–1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silcock C, Liao LM, Hill M, et al. (2015) Will the introduction of non-invasive prenatal testing for Down's syndrome undermine informed choice? Health Expectations 18(5): 1658–1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skutilova V. (2015) Knowledge, attitudes and decision-making in Czech women with atypical results of prenatal screening tests for the most common chromosomal and morphological congenital defects in the fetus: Selected questionnaire results. Biomedical Papers 159(1): 156–1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ternby E, Axelsson O, Annerén G, et al. (2016) Why do pregnant women accept or decline prenatal diagnosis for Down syndrome? Journal of Community Genetics 7(3): 237–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ternby E, Ingvoldstad C, Annerén G, et al. (2015) Information and knowledge about Down syndrome among women and partners after first trimester combined testing. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 94(3): 329–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg M, Timmermans DRM, Ten Kate LP, et al. (2006) Informed decision making in the context of prenatal screening. Patient Education and Counseling 63(1–2): 110–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Heuvel A, Chitty L, Dormandy E, et al. (2009) Is informed choice in prenatal testing universally valued? A population-based survey in Europe and Asia. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 116(7): 880–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Heuvel A, Marteau TM. (2008) Cultural variation in values attached to informed choice in the context of prenatal diagnosis. Seminars in Fetal & Neonatal Medicine 13(2): 99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Steen SL, Houtman D, Bakkeren IM, et al. (2019) Offering a choice between NIPT and invasive PND in prenatal genetic counseling: The impact of clinician characteristics on patients’ test uptake. European Journal of Human Genetics 27(2): 235–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schendel RV, Dondorp WJ, Timmermans DR, et al. (2015) NIPT-based screening for Down syndrome and beyond: What do pregnant women think? Prenatal Diagnosis 35(6): 598–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schendel RV, Page-Christiaens GCL, Beulen L, et al. (2016) Trial by Dutch laboratories for evaluation of non-invasive prenatal testing. Part II—Women’s perspectives. Prenatal Diagnosis 36(12): 1091–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanstone M, Cernat A, Nisker J, et al. (2018) Women’s perspectives on the ethical implications of non-invasive prenatal testing: A qualitative analysis to inform health policy decisions. BMC Medical Ethics 19(1): 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verweij EJ, Oepkes D, De Vries M, et al. (2013) Non-invasive prenatal screening for trisomy 21: What women want and are willing to pay. Patient Education and Counseling 93(3): 641–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, Matsuo M, Ogawa M, et al. (2017) Genetic counseling for couples seeking noninvasive prenatal testing in Japan: Experiences of pregnant women and their partners. Journal of Genetic Counseling 26(3): 628–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B, Lu BY, Zhang B, et al. (2017) Overall evaluation of the clinical value of prenatal screening for fetal-free DNA in maternal blood. Medicine (United States) 96(27): 2–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]