Key Points

Question

Are there any available visual acuity Apple apps suitable for telemedicine use?

Findings

In this study of diagnostic devices, none of the tested visual acuity apps were ideal for telemedicine.

Meaning

While clinicians are limited to apps on iPhone or iPad, these results suggest new and/or improved visual acuity apps are needed for optimal use in telemedicine.

This diagnostic study examines the accuracy and usability of visual acuity–testing apps available in the US Apple App Store.

Abstract

Importance

The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic illustrates the increasingly important role of telemedicine as a method of clinician-patient interaction. However, electronic applications (apps) for the testing of ophthalmology vital signs, such as visual acuity, can be published and used without any verification of accuracy, validity, or reliability.

Objective

To reassess the accuracy of visual acuity–testing apps and assess their viability for telehealth.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The US Apple App Store was queried for apps for visual acuity testing. Anticipated optotype size for various visual acuity lines were calculated and compared against the actual measured optotype size on 4 different Apple hardware devices. No human participants were part of this study.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Mean (SD) errors were calculated per device and across multiple devices.

Results

On iPhones, 10 apps met inclusion criteria, with mean errors ranging from 0.2% to 109.9%. On the iPads, 9 apps met inclusion criteria, with mean errors ranging from 0.2% to 398.1%. Six apps met criteria and worked on both iPhone and iPad, with mean errors from 0.2% to 249.5%. Of the 6 apps that worked across devices, the top 3 most accurate apps were Visual Acuity Charts (mean [SD] error, 0.2% [0.0%]), Kay iSight Test Professional (mean [SD] error, 3.5% [0.7%]), and Smart Optometry (mean [SD] error, 15.9% [4.3%]). None of the apps tested were ideal for telemedicine, because some apps displayed accurate optotype size, while others displayed the same letters on separate devices; no apps exhibited both characteristics.

Conclusions and Relevance

Both Visual Acuity Charts and Kay iSight Test Professional had low mean (SD) errors and functionality across all tested devices, but no apps were suitable for telemedicine. This suggests that new and/or improved visual acuity–testing apps are necessary for optimal telemedicine use.

Introduction

Smartphones and other handheld devices have become increasingly ingrained into daily life.1 There is substantial potential to integrate mobile applications (apps) in clinical ophthalmology.2,3 However, mobile apps can be published without any external testing for validity or reliability yet still may be used widely in clinical practice.4,5 The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic illustrates the increasingly important role of telemedicine as a method of clinician-patient interaction. Given the considerable expansion in number of apps and increasing need for such apps in telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic,6,7 this study aims to assess the accuracy and usability in the context of teleophthalmology of currently available visual acuity testing apps.

Methods

The US Apple App Store was queried for mobile apps that test visual acuity from April 17, 2020, to May 5, 2020. The search terms “eye test,” “Snellen,” “visual acuity,” “vision test,” “optometry,” and “letter chart” were used. Apps were downloaded if they were free, in English, and not in the category of entertainment or advertised as “eye workouts.” Inclusion of a downloaded app in the analysis required that it state the distance to hold the device to measure visual acuity. Data regarding the publisher, rating, most recent update, functionalities of the app, and distance were recorded. Optotype size was manually measured on the iPhone 7, iPhone 11, 11-inch iPad Pro (second generation), and Mini 4 for visual acuity lines 20/200, 20/100, 20/40, and 20/20. The expected optotype size was calculated using the equation Height (in mm) = Inverse of Snellen Fraction × Viewing Distance (in mm) × tan (5/60) and compared with measured optotype size. Mean (SD) errors were calculated per device, and the average mean error was reported across devices. Mean (SD) errors are not available from the apps themselves. A Rosenbaum Near Vision Card was also tested to validate our methodology, with a mean (SD) error of 0.0% (3.7%). Analyses were completed with Excel version 16.16.27 (Microsoft).

This project did not require institutional review board approval. Because this project was non–human subjects research and did not collect or analyze any human data, it did not require a specific institutional review board exemption per the policies of Yale University. For the same reason, no informed consent was necessary.

Results

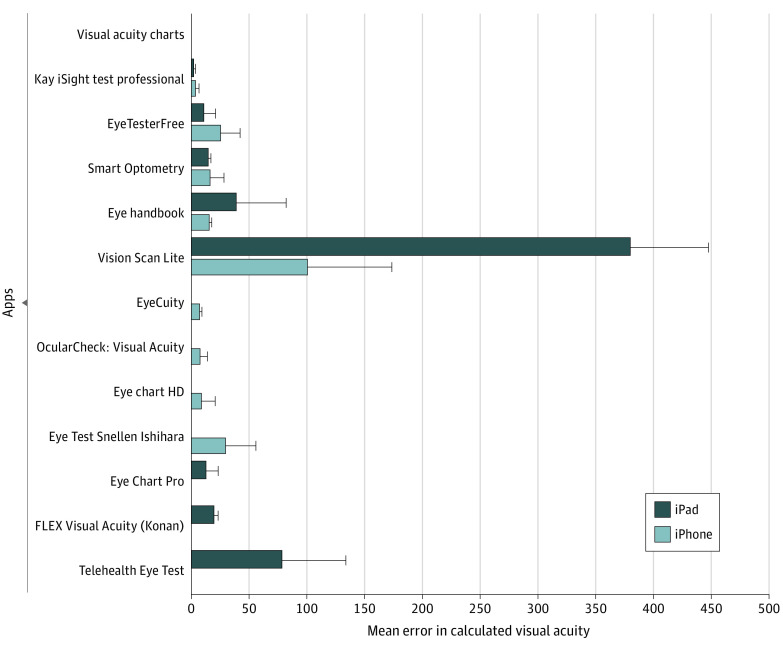

On the iPhones, there were 35 apps downloaded, of which 10 stated the distance to be measured. These had mean errors ranging from 0.2% to 109.9%. One additional app was excluded because of functionality issues. On the iPads, there were 47 apps downloaded, of which 9 stated the distance to be measured, with mean errors ranging from 0.2% to 398.1%. Mean errors for these apps are summarized in the Figure. The mean (SD) error in optotype size across all tested apps was 42.7% (88.7%). Six apps were functional on both iPhone and iPad and stated measurement distance (Table), with mean (SD) errors from 0.2% (0.0%) to 249.5% (130.80%). Of these, the most accurate apps were Visual Acuity Charts (Zijian Huang) (mean [SD] error, 0.2% [0.0%]), Kay iSight Test Professional (Kay Pictures Limited) (mean [SD] error, 3.5% [0.7%]), and Smart Optometry (Smart Optometry DOO) (mean [SD] error, 15.9% [4.3%]).

Figure. Mean (SD) Error of Apps That Work on Either iPhones, iPads, or Both.

Software versions include (from top to bottom) Visual Acuity Charts, version 2.5; Kay iSight Test Professional, 2.1; Smart Optometry, 4.0; EyeTesterFree, 1.5; Eye Handbook, 8.2.12; Vision Scan Lite, 1.3; EyeCuity, 1.0; OcularCheck: Visual Acuity, 1.2.0; Eye Chart HD, 2.3.1; and Eye Test Snellen Ishihara, 4.0.2. Error bars indicate SDs.

Table. Applications (Apps) With Functionality Across the iPhone and iPad.

| App name | App version | Publisher | Distance, cm | Average mean (SD) error, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Acuity Charts | 2.5 | Zijian Huang | 400 | 0.20 (0.00) |

| Kay iSight Test Professional | 2.1 | Kay Pictures Limited | 40 | 3.50 (0.70) |

| Smart Optometry | 4.0 | Smart Optometry DOO | 40 | 15.90 (4.30) |

| EyeTesterFree | 1.5 | FISP Precision Co Ltd | 100 | 18.90 (13.30) |

| Eye Handbook | 8.2.12 | Cloud Nine Development, LLC | 35 | 28.00 (27.40) |

| Vision Scan Lite | 1.3 | Cygnet Infotech, LLC | 60.96 | 249.50 (130.80) |

Abbreviation: DOO, Družba z omejeno odgovornostjo.

Usability was determined to involve acceptable accuracy level, patient accessibility, an inability for patients to zoom in on the letters, letters that were consistent across patient and clinician devices (to permit clinical determination of visual acuity), and a reasonable distance for use. Two apps were accurate enough for clinical use (Kay iSight and Visual Acuity Charts), but Kay iSight did not offer consistent letters and Visual Acuity Charts required a distance of 4 m for use. No app met all the criteria, and thus none were suitable for telemedicine use.

Discussion

None of the tested apps were ideal for virtual consultation telemedicine. For an app to be usable for telemedicine use, it had to be free, so that a patient could easily download it, and accurate, with a low average mean error. In addition, the patient would not be able to zoom into the letters and the letters would be consistent on the patient’s and clinician’s devices. Two apps were accurate enough to be functional for telemedicine; however, both apps had issues making them unsuitable. Kay iSight was the most accurate, but it randomized letters at each use, meaning a clinician working by telephone would not know if the patient was reporting the correct letters. Visual Acuity Charts required the device to be held at 4 m, which is potentially impractical for home use in a telemedicine visit. Other tested apps had similar problems; they were either accurate but displayed random letters or were inaccurate but displayed consistent letters.

A previous study in 2015 also indicated no smartphone app was accurate in visual acuity testing.8 This update on those findings is substantial because the landscape of available apps has evolved significantly; in fact, none of the free apps from the 2015 study are still functional.7

Limitations

Limitations of this study include a lack of actual patient testing using these apps via telemedicine. Evaluation based on actual patient responses rather than expected responses would be ideal; however, because no suitable app for telemedicine was identified, this component of the study was not performed. As a result, it is possible that our evaluation criteria do not truly qualify as an eligibility criterion. Furthermore, this study was limited by the availability of hardware. Because all apps were tested on a variety of Apple devices, these results may not be able to be extrapolated to other device brands (such as Android), other Apple generations, and other sizes of tested devices. However, Apple has the largest market share of not only consumer electronics in the US generally, but also among health care professionals.9,10 That being said, Apple maintains only a 49% market share, meaning that half of the potential market was not evaluated in this investigation. There are examples of visual acuity apps on other platforms.11 Non–English language apps were also excluded, further limiting the number of apps considered for analysis. Contrast was not measured. This may be important for virtual consultations and should be considered when additional app evaluations are conducted.

Conclusions

These results highlight the possibility of passive misinformation, inadvertent or otherwise, spread by publicly available health apps. Given the rise in telemedicine visits within ophthalmology during the COVID-19 pandemic, these apps may be being used across the country to aid clinicians in assessing visual acuity. However, our findings highlight that clinicians would receive inaccurate information, which can substantially alter clinical decision-making. Concern about increasing use of mobile medical apps as a public health issue has been mounting within other medical specialties and is reiterated in this study.12 An app that was published or endorsed by a recognized health organization and externally validated would be useful for home assessment of visual acuity and telemedicine efforts.

References

- 1.Zvornicanin E, Zvornicanin J, Hadziefendic B. The use of smart phones in ophthalmology. Acta Inform Med. 2014;22(3):206-209. doi: 10.5455/aim.2014.22.206-209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chhablani J, Kaja S, Shah VA. Smartphones in ophthalmology. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2012;60(2):127-131. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.94054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lord RK, Shah VA, San Filippo AN, Krishna R. Novel uses of smartphones in ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(6):1274-1274.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coiera EW, Kidd MR, Haikerwal MC. A call for national e-health clinical safety governance. Med J Aust. 2012;196(7):430-431. doi: 10.5694/mja12.10475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chou D. Health IT and patient safety. JAMA. 2012;308(21):2282. doi: 10.1001/jama.308.21.2282-a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng NM, Chakrabarti R, Kam JK. iPhone applications for eye care professionals. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20(4):385-387. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodin A, Shachak A, Miller A, Akopyan V, Semenova N. Mobile apps for eye care in Canada. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017;5(6):e84. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.7055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perera C, Chakrabarti R, Islam FMA, Crowston J. The Eye Phone Study. Eye (Lond). 2015;29(7):888-894. doi: 10.1038/eye.2015.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dolan B. In-depth: mobile adoption among US physicians. Published April 17, 2014. Accessed June 21, 2020. https://www.mobihealthnews.com/32232/in-depth-mobile-adoption-among-us-physicians

- 10.Team Counterpoint . US smartphone market share. Accessed June 21, 2020. Updated November 16, 2020. https://www.counterpointresearch.com/us-market-smartphone-share/

- 11.Bastawrous A, Rono HK, Livingstone IAT, et al. Development and validation of a smartphone-based visual acuity test (peek acuity) for clinical practice and community-based fieldwork. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133(8):930-937. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.1468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akbar S, Coiera E, Magrabi F. Safety concerns with consumer-facing mobile health applications and their consequences. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(2):330-340. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocz175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]