Abstract

This cohort study examines recent trajectories in the incidence of cervical cancer in Puerto Rico by age and among birth cohorts.

In the US, the success of widely implemented screening programs has been associated with a decrease in the incidence of cervical cancer during the last few decades.1 Although national trends in cervical cancer incidence in the contiguous US are well documented,1 recent trends in Puerto Rico (a US territory that is home to nearly 2 million Hispanic or Latino women) are unclear, particularly among age groups and birth cohorts that may have benefited from cervical cancer screening and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination. We evaluated recent trajectories in the incidence of cervical cancer in Puerto Rico by age and among birth cohorts.

Methods

We analyzed the 2001-2017 Puerto Rico Central Cancer Registry data set. Cervical cancer cases were identified based on the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition site codes C53.0 to C53.9 and histology codes 8010 to 8671 and 8940 to 8941. SEER*Stat, version 8.3.8 (Surveillance, Epidemioogy, and End Results Program) was used to calculate incidence rates. Joinpoint Regression Program software, version 4.8.0.1 (Division of Cancer Control & Population Sciences) was used to estimate piecewise–log-linear trends and derive annual percentage changes (APCs) and mean annual percentage changes (MAPCs).2 P values were estimated using the permutation distribution of the test statistic (statistical significance at P < .05, 2-sided). Hysterectomy-corrected incidence trends were assessed by estimating the survey-weighted prevalence of hysterectomy in Puerto Rico from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data and then using it to correct the population at risk by removing the proportion of women with hysterectomy from the denominator. Finally, we used age-period-cohort models to simultaneously evaluate the effect of age, period, and birth cohort on the incidence of cervical cancer. Birth cohort models were fitted using the National Cancer Institute’s Age-Period-Cohort web tool.3 Cohort effects are presented graphically as incidence rate ratios adjusted for age and calendar period effects. The University of Puerto Rico Comprehensive Cancer Center Institutional Review Board approved this study as exempt given that the data are deidentified.

Results

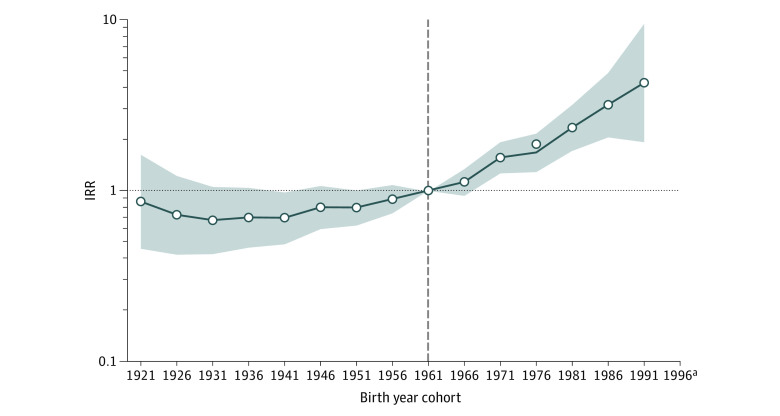

From 2001 to 2017, 3510 cervical cancer cases were diagnosed in Puerto Rico. Overall, cervical cancer incidence per 100 000 person-years increased from 9.2 (95% CI, 7.9-10.7) to 13.0 (95% CI, 10.7%-15.7%), with a MAPC of 2.4% (95% CI, 1.5%-3.3%) (Figure 1A). The hysterectomy-corrected incidence rate increased from 12.2 (95% CI, 10.6-14.3) in 2001 to 16.8 (95% CI, 13.8-19.9) in 2017 (MAPC, 2.0% [95% CI, 1.2%-2.9%]). A marked increase in cervical cancer incidence occurred among women younger than 35 years during the period from 2001 to 2010 (APC, 9.0% [95% CI, 4.9%-13.1%]), followed by a nonsignificant decrease in recent years (2010-2017) (APC, –3.5% [95% CI, –8.7% to –1.9%]). The incidence increased rapidly among women aged 35 to 64 years (MAPC, 2.9% [95% CI, 1.8%-4.0%]). No significant change occurred among women aged 65 years or older (MAPC, –0.7% [95% CI, –2.6% to 1.2]; P = .42) (Figure 1B). Findings were similar when corrected for hysterectomy (Figure 1C). Age-period-cohort modeling showed that, compared with the referent group (women born in 1961), the risk of cervical cancer was more than 4-fold higher (incidence rate ratio, 4.3 [95% CI, 1.9-9.5]) among women born in 1991 (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Trends in Annual Incidence Rates of Cervical Cancer Among Women in Puerto Rico According to Age at Diagnosis: Puerto Rico Central Cancer Registry Data Set (2001-2017).

A, Hysterectomy-corrected and hysterectomy-uncorrected cervical cancer incidence rates. B, Uncorrected cervical cancer incidence rates according to age. C, Hysterectomy-corrected cervical cancer incidence rates according to age. Data markers represent observed incidence rates (cases per 100 000 person-years). Rates are age-adjusted to the 2000 US population. Incidence trends were evaluated for 3 age groups: younger than 35 years (ever vaccine age–eligible group and a portion of screening age–eligible group), 35 to 64 years (screening age–eligible group), and 65 years or older (screening age–ineligible group). The annual percentage change (APC) characterizes trend, a single regression line on a log scale fitted over a fixed interval, whereas the mean annual percentage change (MAPC) is a weighted mean of the APCs from the joinpoint model with the weights equal to the length of the APC interval. Given that there was no joinpoint observed for age groups 35 to 64 years and 65 years or older, the MAPC is equivalent to the APC.

aStatistically significant incidence trend (P < .05).

Figure 2. Incidence Rate Ratios (IRRs) by Birth Cohort for Cervical Cancer: Puerto Rico Central Cancer Registry Data Set (2001-2017).

For comparison, we chose the reference year corresponding to the 1961 cohort (this arbitrary choice of reference year value does not affect result interpretation). Shaded bands indicate 95% CIs. Incidence rate ratios were adjusted for age and calendar period effects.

aNot reported because there were fewer than 16 cases in the time interval.

Discussion

In May 2018, the World Health Organization called for action toward the elimination of cervical cancer. Although the contiguous US population is on track to achieve this goal by 2040,4 increasing rates of cervical cancer in Puerto Rico call for improved cervical cancer prevention in this US territory.

Increasing cervical cancer incidence among women aged 35 to 64 years can be explained by suboptimal cervical cancer screening rates (only 60%) among Puerto Rican women aged 21 to 30 years.5 Furthermore, it is likely that the women may not be undergoing subsequent dysplasia treatment; however, such data are unavailable. The increase in incidence among contemporary birth cohorts may be associated with the increased acquisition of HPV infection. The recent nonsignificant decrease in the incidence of cervical cancer in women 35 years or younger during the period from 2010 to 2017 may indicate the early benefits associated with HPV vaccination. Implementation of the recent HPV vaccination mandate for school entry for children aged 11 to 16 years may improve cervical cancer prevention.6 However, the recent disruption in screening and follow-up caused by Hurricane Maria and the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic implies that continued monitoring of cervical cancer incidence and improvement in prevention are crucial.

References

- 1.Deshmukh AA, Suk R, Shiels MS, et al. Incidence trends and burden of human papillomavirus–associated cancers among women in the United States, 2001-2017. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;djaa128. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19(3):335-351. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenberg PS, Check DP, Anderson WF. A web tool for age-period-cohort analysis of cancer incidence and mortality rates. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(11):2296-2302. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burger EA, Smith MA, Killen J, et al. Projected time to elimination of cervical cancer in the USA: a comparative modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(4):e213-e222. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30006-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . BRFSS prevalence & trends data. Published 2020. Accessed September 3, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/brfssprevalence/

- 6.Lei J, Ploner A, Elfström KM, et al. HPV vaccination and the risk of invasive cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(14):1340-1348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1917338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]