Abstract

Introduction

Individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ) face significant health disparities and barriers to accessing care. Patients have reported provider lack of knowledge as one of the key barriers to culturally responsive, clinically competent care. Many US and Canadian medical schools still offer few curricular hours dedicated to LGBTQ-related topics, and medical students continue to feel unprepared to care for LGBTQ patients.

Methods

We developed a 10-hour LGBTQ health curriculum for preclinical medical and physician assistant students. The curriculum included lectures and case-based small-group discussions covering LGBTQ terminology, inclusive sexual history taking, primary care and health maintenance, and transition-related care. It also included a panel discussion with LGBTQ community members and a small-group practice session with standardized patients. Students were surveyed before and after completing the curriculum to assess for increases in confidence and knowledge related to LGBTQ-specific care.

Results

Forty first- and second-year medical students completed the sessions and provided valid responses on pre- and postcourse surveys. Nearly all students initially felt unprepared to sensitively elicit information, summarize special health needs and primary care recommendations, and identify community resources for LGBTQ individuals. There was significant improvement in students' confidence in meeting these objectives after completion of the five sessions. Knowledge of LGBTQ health issues increased minimally, but there was a significant increase in knowledge of LGBTQ-related terminology.

Discussion

Our 10-hour LGBTQ health curriculum was effective at improving medical students' self-confidence in working with LGBTQ patients but was less effective at increasing LGBTQ-related medical knowledge.

Keywords: LGBT Health, LGBT Terminology, Sexual and Gender Minority, LGBTQ, Transgender, Case-Based Learning, Gender Identity, Human Sexuality, LGBTQ+, Primary Care, Diversity, Inclusion, Health Equity, Editor's Choice

Educational Objectives

By the end of this activity, students will be able to:

-

1.

Sensitively and effectively elicit relevant information about sex anatomy, sexual behavior, sexual history, sexual orientation, and gender identity from all patients.

-

2.

Demonstrate respectful and affirming interpersonal exchanges with others, regardless of gender identity, gender expression, body type, or sexual orientation.

-

3.

Describe historical, political, institutional, and sociocultural factors that may underlie health disparities in LGBTQ individuals.

-

4.

Articulate the special health needs and available options for quality care for LGBTQ patients.

-

5.

Summarize recommended primary care, anticipatory guidance, and health care maintenance for LGBTQ patients.

-

6.

Identify special resources available to support the health and wellness of LGBTQ individuals.

Introduction

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) individuals face significant health disparities and barriers to care.1 The LGBT companion document to Healthy People 20102 and the 2011 Institute of Medicine report3 highlight how some LGBTQ individuals experience significantly higher rates of certain mental health, substance abuse, and chronic medical problems when compared with non-LGBTQ individuals, as well as how some LGBTQ individuals have difficulty obtaining adequate health insurance or may face other forms of discrimination from insensitive providers or health systems.

Attitudes among providers and educators toward LGBTQ patients are likely a contributor to health disparities and barriers to accessing quality care. Meyer's minority stress theory4 has long been used to understand mental health disparities among LGBTQ individuals, and there is evidence to suggest that stressors such as prejudice, discrimination, and stigma may also adversely affect physical health.5 Gender stereotypes, bias, and ridiculing of LGBTQ people may be components of the medical school hidden curriculum,6,7 although some investigators have noted relatively high levels of acceptance of and positive treatment attitudes toward LGBTQ individuals.8 In one survey of US first-year medical students, 46% of respondents possessed some degree of explicit bias toward LGBTQ people, and 82% possessed some degree of implicit bias.9 Almost half of respondents to a survey of Canadian medical students reported witnessing offensive jokes or discriminatory behavior directed toward LGBTQ people by classmates or other health professionals.10 Attitudes toward LGBTQ individuals are more positive among those who self-identify as LGBTQ,8 who have a friend or family member who identifies as LGBTQ,11 or who have had favorable past interactions with LGBTQ individuals.9 This suggests to us that knowledge of the lived experience of LGBTQ people may promote greater acceptance and access to care.

Lack of consistent content related to LGBTQ health in medical education programs likely contributes to LGBTQ health disparities. A 2011 survey12 of US and Canadian medical schools revealed that the median number of hours in the curriculum dedicated to LGBTQ-related content was 5. Nine of the surveyed schools reported 0 hours of LGBTQ-related education in the preclinical years, while 44 reported 0 hours of such content during the clinical years.12 In a 2015 survey13 of US and Canadian medical students, 67% rated the LGBTQ-related curriculum at their school as fair or worse. While many students were comfortable with the topics of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases, most felt unprepared to address topics related to gender transitioning.13 This feeling of unpreparedness was justified by additional work suggesting that many medical students lack actual knowledge of LGBTQ-related medical issues.8 LGBTQ health topics, especially transgender health topics, appear also to be underrepresented in US physician assistant (PA) training programs.14 Recognition of health disparities and the lack of LGBTQ content in medical education prompted the development and publication of AAMC recommendations15 for instituting medical school curricular changes to improve care for LGBTQ individuals.

Similar trends were observed in our home state of Colorado. A 2011 survey16 of LGBTQ Coloradoans revealed that 21% of LGB respondents reported having been refused care by a provider because of their sexual orientation. Among transgender respondents, 53% reported having been refused care on the basis of their gender identity. In the same survey, 65% of LGB respondents and 85% of transgender respondents felt that there were not enough adequately trained providers.16 In a 2013 survey17 of University of Colorado medical students, 25% had witnessed disparaging remarks made by students or residents toward LGBT individuals, and 7% had witnessed such remarks from faculty. At that time, students at the University of Colorado School of Medicine received 3 hours of required LGBT-related content across the 4 years of medical school.

Many health education programs have made efforts over the past decade to improve LGBT-related training and education. The majority of these efforts consist of discrete interventions or chunks of curricular time dedicated to addressing one or more of the gaps described above.18 While these interventions are often elective in nature, it has been recognized that they are often an important first step toward including more LGBT-related content in the required curriculum.18 Despite obvious progress, much remains to be done. Transgender health, in particular, has not yet gained widespread inclusion in health education programs.19 There also remain opportunities to include LGBT-related topics in interprofessional or team-based learning activities and to increase LGBT patient perspectives in all types of learning activities.18

The curriculum described here was developed by students with the assistance of faculty members at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. We intentionally targeted students in the preclinical stage of their training with the hope that doing so would foster empathy and understanding before they encountered LGBTQ patients in the clinical setting. Our primary focus throughout the project was to improve cultural competency and sensitivity. Improving students' knowledge of LGBTQ-specific medical care remained a secondary focus.

Specific examples of initiatives similar to ours can be found throughout the medical education literature.20–25 These examples demonstrate the effectiveness of LGBTQ health education initiatives, but many lack the necessary materials and sufficient detail for easy integration into another institution's preclinical curriculum. MedEdPORTAL has previously published similar content, much of which consists of discrete activities (e.g., case discussions,26,27 standardized patient cases/simulations,28–33 and other brief activities34–37) that are similar to individual components of the curriculum presented here. Some of these publications describe more comprehensive activities but tend to focus on specific skills38–43 or specific subpopulations of LGBTQ individuals,44–46 and many are targeted toward learners at later stages of their training.33,34,41,42,45–50 Our curriculum represents a unique contribution by including a more comprehensive set of activities (including didactic presentations, case discussions, a community panel, and a session with standardized patients) that provide a general overview of LGBTQ-related health topics directed toward learners early in their training. Our curriculum is flexible and inexpensive to implement. It includes annotations and instructions to allow facilitators with minimal expertise in LGBTQ health to deliver the content effectively.

Methods

We developed a 10-hour LGBTQ health-related curriculum targeted toward first- and second-year medical and PA students at the University of Colorado. We delivered the curriculum as an elective course within the School of Medicine, offering it during the spring semester of 2016, the fall semester of 2016, and every subsequent fall semester since that time. We did not require students to have any prior knowledge of course-related material before participating in the course. We actively recruited subject matter experts to facilitate different aspects of the course but also designed the curriculum so that anyone with knowledge of the annotated course materials could effectively deliver the content. At least one facilitator identified as LGBT, but facilitators were not recruited based upon LGBT identity.

Implementation

The course's five 2-hour sessions took place in classrooms on the University of Colorado campus. The first session began with an introductory presentation (Appendix A) covering LGBTQ-related terminology and techniques for taking an inclusive sexual history. An inclusive communication handout (Appendix B) was provided at the beginning of this presentation as a reference for sexual history taking and to offer additional tips for creating an inclusive health care environment. Students then divided into groups of two or three and role-played cases (Appendix C) that allowed them to practice using the terminology and history taking skills learned.

We designed sessions 2–4 so that they could be delivered in any order to allow flexibility in scheduling facilitators and community panelists. We dedicated session 2 to discussion of LGBTQ adult health issues. It included presentations (Appendices D and E) covering health disparities among LGBTQ adults, primary care recommendations and anticipatory guidance for LGBTQ adults, and general principles of transition-related care for transgender adults. The didactic session was followed by small-group, case-based discussion (Appendices F and G).

Issues specific to LGBTQ children and adolescents were discussed in session 3. This session's presentation (Appendix H) focused on health disparities among transgender youth, specific challenges in working with transgender youth (persistence/desistance of transgender identity through childhood, working with parents of transgender youth), and best-practice recommendations for transgender adolescents wishing to transition.

Session 4 consisted entirely of a panel discussion (Appendix I) with members of the LGBTQ community. The Gender Identity Center of Colorado and the GLBT Community Center of Colorado assisted in identifying members of the community to sit on the panel. They also provided facilitators familiar with the panelists to guide the discussion. We aimed to include four to five panelists, with diversity in race/ethnicity, gender identity, and sexual orientation. We asked panelists to come prepared to share their experiences with the health care system, including challenges they had faced in accessing care, experiences that were particularly invalidating, and any that were empowering. Panelists were provided free parking for the session, but we were otherwise not able to compensate them for their participation.

The final session began with a 1-hour practice using standardized patients (Appendix J). Students divided into small groups and rotated through three cases. Several suitable cases were available through MedEdPORTAL and elsewhere in the medical education literature. We used the case of Gerald Moore, for example, which can be found among a collection of cases published in MedEdPORTAL.39 The remaining cases were developed to train patient navigators at one of our affiliated hospitals, and we have not been permitted to reproduce them here. Appendix J contains guidance for selecting alternative cases. We were not involved in the casting or training of our standardized patients, and the sexual orientation and gender identity of those who portrayed our cases were not known. However, our simulation center routinely makes efforts to match the sexual orientation and gender identity of the standardized patient to the role being portrayed in a case. The practice session took place in the same classroom space as the other sessions but could easily be adapted to a more clinically authentic setting. We elected to have students interview the patients in groups for the purpose of efficiency (given a significant time constraint). We also noted that interviewing in groups made the experience less intimidating for students with limited clinical experience. The session could easily be adapted to allow students to interview patients one-on-one. A debriefing period immediately followed the practice session, giving students the opportunity to discuss the experience and challenges they had encountered.

Evaluation

Students completed pre- and postcourse surveys (Appendices K and L) immediately prior to the first session and immediately following the last session, respectively. The surveys measured the effectiveness of the curriculum in two domains. We assessed students' self-reported confidence in meeting course objectives using a four-point Likert scale and assessed acquisition of knowledge related to LGBTQ health using five multiple-choice or true/false questions. The precourse survey included free-response items that asked students to identify their goals in taking the course as well as any previous training or experience they might have had working with LGBTQ individuals. Students were not asked to disclose their own sexual orientation or gender identity but were not discouraged from doing so. Students assigned themselves a unique identifier at the beginning of the course. This identifier was used on both surveys to track changes in survey responses across the course. Our evaluation strategy was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Data Analysis

Data from three semesters were pooled for the purpose of analysis. Temporal changes in student performance across the three semesters were not assessed. Responses to the self-confidence items were converted to a numeric scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree). Responses to the five knowledge questions were converted to a numeric score (percentage correct) for each question and for all combined. Responses for which valid pre- and postcourse responses could not be matched were excluded from further analysis. Means and 95% confidence intervals for pre- and postcourse responses and scores were calculated using R (version 3.5.1, R Foundation). Paired-samples t tests (also performed in R) were used to determine statistical significance between pre- and postcourse responses. Bonferroni corrections were applied where appropriate to account for multiple comparisons.

We also performed a subgroup analysis based upon students' reports of previous training or experience working with LGBTQ individuals to examine potential confounding effects. Means and 95% confidence intervals for pre- and postcourse responses were calculated for each subgroup (previous experience vs. no previous experience). Statistical significance was determined with paired-samples t tests using R, again applying a Bonferroni correction to account for multiple comparisons.

Results

A total of 49 students enrolled in the course from the spring semester of 2016 through the fall semester of 2017. Course enrollment varied from 14–19 students per semester. All were first- or second-year students in the School of Medicine's MD program. We actively recruited from the School of Medicine's PA program, but scheduling differences between the MD and PA programs made it difficult for PA students to attend, and no PA students participated. Among those who enrolled, 20 (41%) reported having no previous training or experience working with LGBTQ individuals. Ten (20%) reported having such experience in the non-health care setting, while 15 (31%) reported experience working with LGBTQ individuals in a health care setting. Four (8%) reported previous experiences working with LGBTQ individuals in both health care and non-health care settings.

Self-Confidence

Of the 49 students, 42 provided valid ratings of self-confidence in meeting course objectives on both the pre- and postcourse surveys. The remaining seven either were not present on the first or last day of the course (three), withdrew after the first session (one), or chose not to provide a rating for one or more objectives (three). Three responses fell outside the range of the forced-choice Likert scale and were discarded.

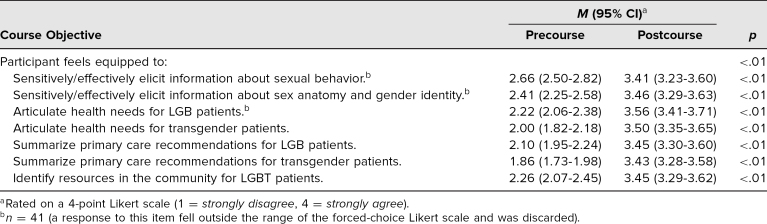

Table 1 summarizes the pre- and postcourse self-confidence ratings for seven items directly related to the course objectives. During the precourse survey, students almost exclusively disagreed (a rating of 1 or 2) that they felt capable of meeting any of the seven objectives. Following the course, students nearly exclusively agreed (a rating of 3 or 4) that they felt capable of meeting all objectives. The increase in self-reported confidence was statistically significant (p < .01) for all seven objectives.

Table 1. Self-Confidence in Meeting Course Objectives (n = 42).

Knowledge Acquisition

Forty students provided responses to all five of the knowledge acquisition questions on both the pre- and postcourse surveys. Nine were excluded due to the reasons described above.

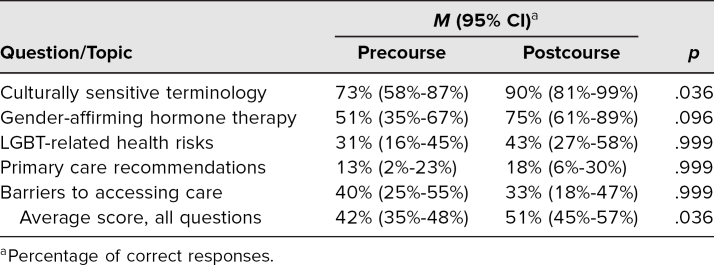

Table 2 summarizes students' total scores (percentage correct) on the knowledge portion of the survey, as well as the percentage of correct responses for each question. Average total score on the knowledge acquisition portion of the survey improved only minimally, from 42% to 51% (p = .036). When we examined the questions independently, we did observe more substantial improvement in performance on the question related to culturally sensitive terminology (from 73% to 90%, p = .036).

Table 2. Performance on Knowledge Acquisition Questions (n = 40).

Subgroup Analysis

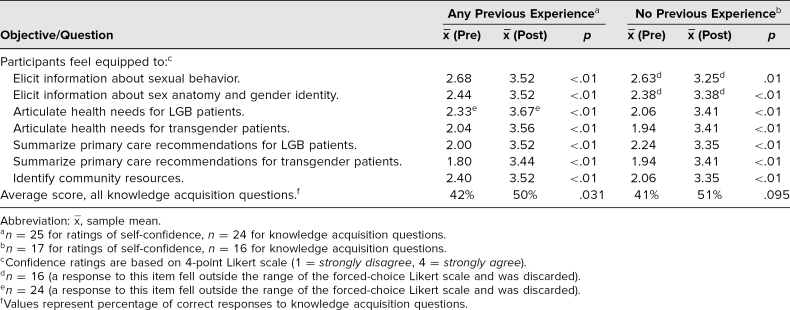

Table 3 summarizes the results of our subgroup analysis based upon students' reports of previous training or experience working with LGBTQ individuals at the time of the precourse survey. Students in both groups (no previous experience vs. any previous experience) reported similar ratings of self-confidence in meeting course objectives. The increase in self-confidence between the pre- and postcourse surveys remained statistically significant (p ≤ .01) in both groups of students for each of the seven measures. The minimal improvement in average score for the knowledge acquisition portion of the survey was similar among the two subgroups and consistent with the combined performance of all respondents.

Table 3. Performance Among Participants With and Without Previous Training/Experience.

Discussion

Our elective 10-hour LGBTQ health curriculum significantly improved students' self-confidence in their ability to sensitively and effectively elicit information about sexual behavior, sex anatomy, and gender identity from sexual and gender minority patients; summarize health needs and primary care recommendations for LGBTQ patients; and identify resources in the community providing support to LGBTQ individuals. There remained a significant increase in self-confidence even among students who reported previous training or experience working with LGBTQ individuals, demonstrating that the curriculum remains useful for students with a wide variety of previous experience.

The poor performance on the knowledge acquisition questions was disappointing. Our students were at an early stage of their medical education and may have performed better if they had more foundational medical knowledge and clinical experience. Few studies have evaluated similar interventions among preclinical medical students. Many have relied on qualitative methods or students' self-reported attitudes and confidence. One intervention among second-year medical students at the University of California, San Francisco, demonstrated a statistically significant increase in knowledge related to LGBTQ relationships and access to health care, in addition to improved attitudes and willingness to provide care.22 The overall magnitude of the change was small (0.57 on a 5-point scale). The same intervention failed to demonstrate significant change in 12 of its 16 survey items.22

We also recognize that the format of our knowledge acquisition questions was suboptimal and that the questions we used probably did not reflect the most important learning objectives from each session. We continued to use these questions throughout multiple iterations of the course to maintain a consistent evaluation strategy. We would recommend reevaluating these questions if assessing knowledge acquisition is an important goal for future programs.

We have gone to great lengths to ensure that most of our materials are readily generalizable; however, there are some activities that may be challenging to implement in some settings. For the panel discussion with LGBTQ community members, we relied on local LGBTQ advocacy organizations for assistance with recruiting panelists. These organizations have been tremendously helpful in identifying people willing to discuss and answer sensitive questions but may not exist in some communities. We have included guidance for recruiting panelists in the instructions for this session. Invoking the assistance of LGBTQ-friendly providers in the community may also be helpful.

The second challenge to generalizability comes from the standardized patient session. We are fortunate at the University of Colorado to have access to excellent clinical simulation resources, but we recognize that access to similar resources may not be available at other institutions. We also recognize that the use of standardized patients is the costliest aspect of implementing our curriculum and may be a limiting factor. However, there is some flexibility in how this session can be implemented to minimize cost. For example, we chose to hold the standardized patient practice sessions in a classroom instead of in more clinically authentic spaces on campus. We chose to have our students interview standardized patients in small groups instead of individually, reducing the amount of time and the number of patients needed. We also reused cases that were already being used for similar purposes elsewhere in our health system. This saved us the expense of training the standardized patients but limited our control over case selection and casting of standardized patients.

Our evaluation strategy was limited by the elective nature of the course. Students were self-selected, and it is likely that our students entered the course with more prior experience with LGBTQ individuals and more positive attitudes toward such individuals than the general population of medical students at our institution. This seems to be supported by the finding that 59% of our students reported previous training or experience working with LGBTQ individuals at the start of the course. However, we would have expected prior experience to bias confidence ratings toward higher precourse ratings and lower overall improvement in ratings across the course, and this effect was not seen. We suspect that those with previous LGBT-related experience likely entered the course with a better understanding of the nuances and challenges of working with this diverse population.

We hope that the work presented here will result in an increase in the number of required hours devoted to LGBTQ health in the preclinical curriculum at the University of Colorado and at other institutions. Integrating new material into the required curriculum is challenging when it means the elimination of hours devoted to other topics. The curriculum remains optional for preclinical medical students at the University of Colorado, though we continue to look for opportunities to integrate these activities into our required curriculum. The curriculum could easily be shortened by separating the cultural sensitivity content from the health-related content, allowing the former to be made required while continuing to offer the latter as elective content.

Appendices

- Session 1 Slides - Terms and Terminology.pptx

- Session 1 Handout - Inclusive Communication.docx

- Session 1 Handout - Terms and Terminology Role-Plays.docx

- Session 2 Slide Set 1 - Health Disparities.pptx

- Session 2 Slide Set 2 - Adult LGBT Health.pptx

- Session 2 Discussion Guide - Adult LGBT Health Care Cases.docx

- Session 2 Handout - Adult LGBT Health Care Cases.docx

- Session 3 Slides - Caring for LGBTQ Youth.pptx

- Session 4 Instructions - Patient Panel.docx

- Session 5 Instructions - Group Role-Play.docx

- Precourse Survey.docx

- Postcourse Survey.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.

Acknowledgments

Rita S. Lee, MD (University of Colorado), donated instructional time and resources throughout the course and provided financial support for working with standardized patients. Natalie Nokoff, MD (University of Colorado), donated instructional time and materials throughout the project. Daniel Reirden, MD (University of Colorado), donated instructional time and materials during early parts of this project. Kirsten Broadfoot, PhD, and the Center for Advancing Professional Excellence at the University of Colorado provided standardized patients and support for working with standardized patients throughout this project. The Gender Identity Center of Colorado and the GLBT Community Center of Colorado provided access to staff and community members for panel discussions throughout the project. The following individuals at the University of Colorado also provided support or resources during the design and implementation of this project: Austin Butterfield, MD, Robin Christian, MD, Michele Doucette, PhD, Philipp Hannan, MD, Tai Lockspeiser, MD, Steve Lowenstein, MD, Carrie Myers, and Rachel Sewell, MD.

Disclosures

None to report.

Funding/Support

None to report.

Ethical Approval

The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board approved this study.

References

- 1.Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health. Healthy People. Accessed April 7, 2019. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-health

- 2.Gay and Lesbian Medical Association, LGBT Health Experts. Healthy People 2010 Companion Document for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Health. Gay and Lesbian Medical Association; 2001. http://glma.org/_data/n_0001/resources/live/HealthyCompanionDoc3.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674–697. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lick DJ, Durso LE, Johnson KL. Minority stress and physical health among sexual minorities. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2013;8(5):521–548. 10.1177/1745691613497965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng LF, Yang HC. Learning about gender on campus: an analysis of the hidden curriculum for medical students. Med Educ. 2015;49(3):321–331. 10.1111/medu.12628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fallin-Bennett K. Implicit bias against sexual minorities in medicine: cycles of professional influence and the role of the hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 2015;90(5):549–552. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lapinski J, Sexton P, Baker L. Acceptance of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients, attitudes about their treatment, and related medical knowledge among osteopathic medical students. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2014;114(10):788–796. 10.7556/jaoa.2014.153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burke SE, Dovidio JF, Przedworski JM, et al. Do contact and empathy mitigate bias against gay and lesbian people among heterosexual first-year medical students? A report from the Medical Student CHANGE Study. Acad Med. 2015;90(5):645–651. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nama N, MacPherson P, Sampson M, McMillan HJ. Medical students' perception of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) discrimination in their learning environment and their self-reported comfort level for caring for LGBT patients: a survey study. Med Educ Online. 2017;22(1):1368850 10.1080/10872981.2017.1368850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chapman R, Watkins R, Zappia T, Nicol P, Shields L. Nursing and medical students' attitude, knowledge and beliefs regarding lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender parents seeking health care for their children. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(7–8):938–945. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03892.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Obedin-Maliver J, Goldsmith ES, Stewart L, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-related content in undergraduate medical education. JAMA. 2011;306(9):971–977. 10.1001/jama.2011.1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White W, Brenman S, Paradis E, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patient care: medical students' preparedness and comfort. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27(3):254–263. 10.1080/10401334.2015.1044656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seaborne LA, Prince RJ, Kushner DM. Sexual health education in U.S. physician assistant programs. J Sex Med. 2015;12(5):1158–1164. 10.1111/jsm.12879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollenbach AD, Eckstrand KL, Dreger A, eds. Implementing Curricular and Institutional Climate Changes to Improve Health Care for Individuals Who Are LGBT, Gender Nonconforming, or Born With DSD: A Resource for Medical Educators. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2014. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/c/2/157460-implementing_curricular_climate_change_lgbt.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16.Invisible: The State of LGBT Health in Colorado. One Colorado Education Fund; 2011. https://one-colorado.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/OneColorado_HealthSurveyResults.pdf

- 17.Dhaliwal JS, Crane LA, Valley MA, Lowenstein SR. Student perspectives on the diversity climate at a U.S. medical school: the need for a broader definition of diversity. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:154 10.1186/1756-0500-6-154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Streed CG Jr, JA Davis. Improving clinical education and training on sexual and gender minority health. Curr Sex Health Rep. 2018;10(4):273–280. 10.1007/s11930-018-0185-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubin SN, Nolan IT, Streed CG Jr, Greene RE, Radix AE, Morrison SD. Transgender health care: improving medical students' and residents' training and awareness. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:377–391. 10.2147/AMEP.S147183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braun HM, Garcia-Grossman IR, Quiñones-Rivera A, Deutsch MB. Outcome and impact evaluation of a transgender health course for health profession students. LGBT Health. 2017;4(1): 55–61. 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grosz AM, Gutierrez D, Lui AA, Chang JJ, Cole-Kelly K, Ng H. A student-led introduction to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health for first-year medical students. Fam Med. 2017;49(1):52–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelley L, Chou CL, Dibble SL, Robertson PA. A critical intervention in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health: knowledge and attitude outcomes among second-year medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2008;20(3):248–253. 10.1080/10401330802199567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sawning S, Steinbock S, Croley R, Combs R, Shaw A, Ganzel T. A first step in addressing medical education curriculum gaps in lesbian-, gay-, bisexual-, and transgender-related content: the University of Louisville Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Certificate Program. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2017;30(2):108–114. 10.4103/efh.EfH_78_16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sequeira GM, Chakraborti C, Panunti BA. Integrating lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) content into undergraduate medical school curricula: a qualitative study. Ochsner J. 2012;12(4):379–382. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solotke M, Sitkin NA, Schwartz ML, Encandela JA. Twelve tips for incorporating and teaching sexual and gender minority health in medical school curricula. Med Teach. 2019;41(2):141–146. 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1407867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin H, Dasgupta S. Genetics in LGB assisted reproduction: two flipped classroom, progressive disclosure cases. MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13:10607 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leslie KF, Steinbock S, Simpson R, Jones VF, Sawning S. Interprofessional LGBT health equity education for early learners. MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13:10551 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curren C, Thompson L, Altneu E, Tartaglia K, Davis J. Nathan/Natalie Marquez: a standardized patient case to introduce unique needs of an LGBT patient. MedEdPORTAL. 2015;11:10300 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10300 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eckstrand K, Lomis K, Rawn L. An LGBTI-inclusive sexual history taking standardized patient case. MedEdPORTAL. 2012;8:9218 https://www.mededportal.org/doi/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9218 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gelman A, Amin P, Pletcher J, Fulmer V, Kukic A, Spagnoletti C. A standardized patient case: a teen questioning his/her sexuality is bullied at school. MedEdPORTAL. 2014;10:9876 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9876 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang B, Milling D, Dimiduk S, Nair H, Zinnerstrom K. Depression in the LGBT patient: a standardized patient encounter. MedEdPORTAL. 2014;10:9759 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9759 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCave EL, Aptaker D, Hartmann K, Zucconi R. Promoting affirmative transgender health care practice within hospitals: an IPE standardized patient simulation for graduate health care learners. MedEdPORTAL. 2019;15:10861 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Underman K, Giffort D, Hyderi A, Hirshfield LE. Transgender health: a standardized patient case for advanced clerkship students. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10518 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooper MB, Chacko M, Christner J. Incorporating LGBT health in an undergraduate medical education curriculum through the construct of social determinants of health. MedEdPORTAL. 2018;14:10781 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gavzy SJ, Berenson MG, Decker J, et al. The case of Ty Jackson: an interactive module on LGBT health employing introspective techniques and video-based case discussion. MedEdPORTAL. 2019;15:10828 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mehringer J, Bacon E, Cizek S, Kanters A, Fennimore T. Preparing future physicians to care for LGBT patients: a medical school curriculum. MedEdPORTAL. 2013;9:9342 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9342 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saba G, Satterfield J, Salazar R, et al. The SBS Toolbox: clinical pearls from the social and behavioral sciences. MedEdPORTAL. 2010;6:7980 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.7980 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bakhai N, Ramos J, Gorfinkle N, et al. Introductory learning of inclusive sexual history taking: an e-lecture, standardized patient case, and facilitated debrief. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10520 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee R, Loeb D, Butterfield A. Sexual history taking curriculum: lecture and standardized patient cases. MedEdPORTAL. 2014;10:9856 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9856 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mayfield JJ, Ball EM, Tillery KA, et al. Beyond men, women, or both: a comprehensive, LGBTQ-inclusive, implicit-bias-aware, standardized-patient-based sexual history taking curriculum. MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13:10634 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oller D. Cancer screening for transgender patients: an online case-based module. MedEdPORTAL. 2019;15:10796 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Potter J, Fessler D, Huang G, Baker J, Dearborn H, Libman H. Challenging pelvic exam. MedEdPORTAL. 2015;11:10256 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10256 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Potter LA, Burnett-Bowie SAM, Potter J. Teaching medical students how to ask patients questions about identity, intersectionality, and resilience. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10422 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ahmad T, Yan H, Guidolin K, Foster P. Medical queeries: transgender healthcare. MedEdPORTAL. 2015;11:10068 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bakhai N, Shields R, Barone M, Sanders R, Fields E. An active learning module teaching advanced communication skills to care for sexual minority youth in clinical medical education. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10449 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Calzo JP, Melchiono M, Richmond TK, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescent health: an interprofessional case discussion. MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13:10615 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gallego J, Knudsen J. LGBTQI’ defined: an introduction to understanding and caring for the queer community. MedEdPORTAL. 2015;11:10189 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grubb H, Hutcherson H, Amiel J, Bogart J, Laird J. Cultural humility with lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: a novel curriculum in LGBT health for clinical medical students. MedEdPORTAL. 2013;9:9542 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9542 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sullivan W, Eckstrand K, Rush C, Peebles K, Lomis K, Fleming A. An intervention for clinical medical students on LGBTI health. MedEdPORTAL. 2013;9:9349 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ufomata E, Eckstrand KL, Spagnoletti C, et al. Comprehensive curriculum for internal medicine residents on primary care of patients identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:10875 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- Session 1 Slides - Terms and Terminology.pptx

- Session 1 Handout - Inclusive Communication.docx

- Session 1 Handout - Terms and Terminology Role-Plays.docx

- Session 2 Slide Set 1 - Health Disparities.pptx

- Session 2 Slide Set 2 - Adult LGBT Health.pptx

- Session 2 Discussion Guide - Adult LGBT Health Care Cases.docx

- Session 2 Handout - Adult LGBT Health Care Cases.docx

- Session 3 Slides - Caring for LGBTQ Youth.pptx

- Session 4 Instructions - Patient Panel.docx

- Session 5 Instructions - Group Role-Play.docx

- Precourse Survey.docx

- Postcourse Survey.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.