Abstract

Introduction:

Despite great efforts, tuberculosis (TB) is still a major public health threat worldwide. For decades, TB control programs have focused almost exclusively on infectious TB active cases. However, it is evident that this strategy alone cannot achieve TB elimination. To achieve this objective a comprehensive strategy directed toward integrated latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) management is needed. Recently it has been recognized that LTBI is not a stable condition but rather a spectrum of infections (e.g., intermittent, transient or progressive) which may lead to incipient, then subclinical, and finally active TB disease.

Aim:

Provide an overview of current available LTBI diagnostic test including updates, future developments and perspectives.

Results:

There is currently no test for the direct identification of live MT infection in humans. The diagnosis of LTBI is indirect and relies on the detection of an immune response against MT antigens, assuming that the immune response has developed after a contact with the biological agent. Tuberculin skin test (TST) and interferon gamma release assays (IGRAs) are the main diagnostic tools for LTBI, however, both present strengths and limitations. The most ancient diagnostic test (TST) can be associated with several technical errors, has limited positive predictive value, is being influenced by BCG vaccination and several conditions can reduce the skin reactivity. Notwithstanding these limitations, prompt identification of TST conversion, should orientate indications for preventive therapy of LTBI. IGRAs have superior specificity, are not affected by M. bovis, BCG vaccination and other environmental mycobacteria. However, they present some logistical and organisational constraints and are more expensive. Currently, the WHO guidelines recommend that either a TST or an IGRA can be used to detect LTBI in high-income and upper middle-income countries with estimated TB incidences less than 100 per 100,000 population. Two skin tests (C-TB and Diaskintest), using only two specific M. tuberculosis antigens (ESAT-6 and CFP-10) instead of the tuberculin solution, have recently been developed but, to date, none of these tests is available on the European market.

Conclusion:

Early identification and treatment of individuals with LTBI is an important priority for TB control in specific groups at risk within the population: this is of crucial meaning in recently infected cases both at the community level and in some occupational settings. Currently there is no gold standard test for LTBI: an improved understanding of the available tests is needed to develop better tools for diagnosing LTBI and predicting progression to clinical active disease.

Key words: Tuberculosis, TB, latent tuberculosis infection, LTBI, diagnostic tests, elimination, occupational health, public health

Abstract

Introduzione:

Nonostante i grandi sforzi compiuti, la tubercolosi (TB) costituisce ancora uno dei principali problemi di salute pubblica a livello globale. Per decenni i programmi di prevenzione si sono orientati quasi esclusivamente sul controllo e sulla gestione dei casi di TB attiva contagiosa. Tuttavia, è evidente che questa strategia da sola non è in grado di consentire l’eliminazione della malattia. Al fine di raggiungere questo obiettivo è necessaria una strategia rivolta all’identificazione e alla gestione dell’infezione da tubercolosi latente (ITBL). Recentemente è stato descritto come l’ITBL non sia una condizione stabile, ma piuttosto uno spettro di infezioni (es., intermittente, transitoria o progressiva) che può portare a quadri definibili come incipiente, quindi subclinica e, infine, malattia attiva.

Obiettivo:

Fornire una panoramica degli attuali test diagnostici disponibili per ITBL, con un aggiornamento sugli sviluppi e le prospettive future.

Risultati:

Attualmente non è disponibile un test per l’identificazione diretta dell’infezione da MT vivente nell’uomo. La diagnosi di ITBL è indiretta e si basa sulla rilevazione di una risposta immunitaria contro gli antigeni del Mycobacterium Tuberculosis (MT), presumendo che la risposta immunitaria si sia sviluppata dopo un contatto con l’agente biologico. Il test cutaneo alla tubercolina (TST) e i test su siero basati sul rilascio di interferone gamma (IGRA) sono i principali strumenti diagnostici per ITBL, tuttavia, entrambi presentano punti di forza e limiti. Il test diagnostico più antico (TST) può essere associato a diversi errori tecnici, ha un limitato valore predittivo positivo, è influenzato dalla vaccinazione BCG e diverse condizioni possono ridurre la reattività cutanea. Nonostante queste limitazioni, la rapida identificazione di una cuti-conversione al TST può orientare le indicazioni per la terapia preventiva dell’ITBL. L’IGRA ha una specificità superiore, non è influenzato dal M. bovis, dalla vaccinazione con BCG e da altri micobatteri ambientali. Tuttavia, presenta alcuni svantaggi logistici e organizzativi ed è più costoso. Attualmente, le linee guida dell’OMS raccomandano di utilizzare un TST o un IGRA per la diagnosi di LTBI in paesi a elevato e medio-alto reddito con incidenza di tubercolosi stimata inferiore a 100 per 100.000 abitanti. Di recente sono stati sviluppati due test cutanei (C-TB e Diaskintest) utilizzando solo due antigeni specifici di M. tuberculosis (ESAT-6 e CFP-10) invece della soluzione di tubercolina ma, a oggi, nessuno dei test è disponibile sul mercato europeo.

Conclusioni:

L’identificazione precoce e il trattamento degli individui con ITBL rappresenta una priorità per il controllo della TB in specifici gruppi a rischio all’interno della popolazione: questo aspetto risulta cruciale negli individui recentemente infettati sia a livello di comunità sia in alcuni contesti occupazionali. A oggi non esiste un test definibile come gold standard per la diagnosi d’ITBL: è pertanto necessaria una migliore comprensione dei test disponibili al fine di sviluppare migliori strumenti per la diagnosi dell’infezione e per predirne la progressione a malattia clinica attiva.

Introduction

Despite great efforts, tuberculosis (TB) is still a major public health threat worldwide, with 10 million new cases and 1.2 million deaths in 2018 (56). One fourth of the global population (approximately 2 billion persons) is estimated to be infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MT) (11, 19), including approximately 13 million people in the United States (35).

Most infected individuals are asymptomatic and classified as having latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI). LTBI is defined by the Word Health Organization (WHO) as a state of persistent immune response to MT antigens, with no evidence of clinically manifest active TB (55); thus, this condition identifies the individuals who have being in contact with MT and have developed an immune response, but this does not imply necessarily the persistence of living pathogens in the human body (30). The vast majority of infected people have no signs or symptoms of TB and will never develop the disease.

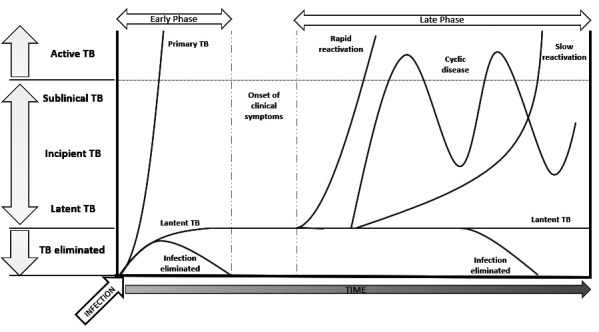

The risk of developing active TB following infection depends on age, the quality of the immune defense mechanisms, and the time elapsed since the infection. The estimated liftetime risk is 5-10%, but it is higher in small children, immunocompromised individuals, and shortly (within 1-2 years) after a contact with a contagious TB case. LTBI is not a stable state; intermittent, transient or progressive episodes of mycobacterial replication can lead to incipient, then subclinical, and finally active TB disease (Fig. 1) (13).

Figure 1.

The natural history of tuberculosis disease: pathways of progression; adapted from Drain et al. (13)

In high-income countries, the incidence of active TB disease has continued to decline over the recent decades, but the prevalence of LTBI has remained stable.

For decades, TB control programs have focused almost exclusively on infectious TB cases. Active case finding and proper management of active TB should be the top priority for control programs. However, it is evident that this strategy alone cannot achieve TB elimination. This important objective can be achieved through comprehensive strategies aimed at a proper and integrated LTBI and active TB management (27, 32). In fact, because a majority of new TB cases are a result of reactivation of remote LTBI rather than recent infection, intensification of LTBI screening and treatment strategies is recognized as a crucial component of TB elimination, especially in low TB prevalence settings. LTBI is a large reservoir for active TB and progression from untreated LTBI accounts for approximately 80% of U.S. TB disease cases.

The WHO action plan for TB elimination in low-incidence countries (28) (defined as those with a TB notification rate of <100 TB cases - all forms - per million population) highlighted the public health role of screening for active TB and LTBI in contacts of infectious cases. One of the priority actions in low TB incidence countries is the identification of contagious cases to implement contact tracing and prevent new incident cases of active TB.

Early diagnosis of LTBI after a documented or suspected exposure is key in order to assess the risk of active TB and to provide prompt preventive treatment. Therefore, detecting groups at higher risk of developing the disease is needed both at the community and occupational levels in low incidence countries in order to eliminate TB (17).

It has been reported that MTB transmission is more likely in some confined environments such as healthcare settings (42, 51), long-term care facilities, high-congregate settings (e.g., homeless shelters, prisons, schools) with an increased risk for patients, residents and workers alike. Indeed, this is valid in prison settings for both LTBI and TB (7, 9, 16, 26, 36), as well as in other congregate settings with asylum seekers and migrants from high TB incidence countries (5, 8, 12, 15, 21, 25, 29, 45). Poor hygiene conditions, poor ventilation, and high density of contagious residents and co-workers could explain the increased risk of MT transmission in these settings (37).

Occupational physicians and specialists in preventive medicine can play a key-role in the implementation of LTBI surveillance, early diagnosis, and preventive therapy in categories and individuals with a higher risk than the general population of being exposed to MTB and/or to develop active TB. In this view, TB risk-assessment in the occupational context needs to focus on the following items: (I) local epidemiology and working environment conditions (e.g., healthcare and specific high-congregate settings); (II) high risk-medical procedures (e.g., bronchoscopy, respiratory rehabilitation); and (III) individual risk factors associated with progression from LTBI to active disease (e.g., co-morbidities, iatrogenic immune depression).

This paper briefly summarizes the recent acquired knowledge on LTBI and current available diagnostic tools, also reporting future developments and challenges in the diagnosis. A better knowledge and comprehension of the available diagnostic tests for LTBI diagnosis, including their strengths and limitations, as well as their intergroup applicability, can be useful to properly identify and manage this condition in order to eliminate TB.

Available tests for LTBI

There is currently no test for the direct identification of living MT infection in humans.

The diagnosis of LTBI is indirect and relies on the detection of an immune response against MT antigens, asssuming that the immune response has developed after a contact with MT. Tuberculin skin test (TST) and interferon gamma release assays (IGRAs) are the main diagnostic tests for LTBI; both are indirect tests based on immune response to TB and do not directly assess the presence or viability of TB bacilli.

Furthermore, no test is currently available which would allow the distinction between an immune reaction due to LTBI from that induced by active TB.

Thus, the distinction between LTBI and active TB relies on clinical, bacteriological, and radiological findings.

Current available LTBI diagnostic test are reported and discussed below.

The tuberculin skin test (TST)

The classical test for the detection of LTBI is the TST, the most ancient diagnostic test still in use in medicine, which relies on the reaction against MT antigens injected in the dermis of the skin. The intensity of the local inflammatory reaction due to the release of cytokines by sensitized lymphocytes is measured after 48 to 72 hours and has been shown by some Authors to be correlated with the risk of future TB (20, 38).

TST is cheap, can be performed anywhere by any healthcare workers with adequate trainig without the need of technical equipment, except a cold chain for keeping the tuberculin solution. Nevertheless, the test is characterized by a large number of drawbacks which makes its use far from ideal. Moreover, tuberculin solution contains a large number of antigens (~200), most of which are common to M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, BCG, and environmental mycobacteria: a positive test reaction can, therefore, be elicited by a prior vaccination with BCG or a contact with environmental mycobacteria and has a low specificity (49). Furthermore, the technique for placing tuberculin and reading the reaction can be associated with several technical errors (e.g., injection in the wrong skin layer, fluid leaks, subjective evaluation of the skin reaction with intra- and inter-observer errors). Several conditions can decrease the skin reactivity, such as viral infections, immune depression, young and old age (Tab.1). Repeating the test can elicit an artificial increase in size of the second reaction (the so-called “booster effect”) (34). Furthermore, the test is performed without any positive or negative control and the quality of the tuberculin can also influence the proportion of reactions interpreted as positive (39).

Another limitation is the limited predictive value for TB disease. In other words, a majority of subjects with positive TST results do not progress to active TB disease, so overtreatment is inevitable, since there is no way to know which individual with a positive TST result will actually benefit from LTBI therapy. Notwithstanding these limitations, prompt identification of TST conversion, shortly after a contact with an infectious case, should orientate the indication for preventive therapy.

Interferon Gamma Release Assays (IGRAs)

An alternative test is the blood-based test relying on the in vitro measurement of gamma-interferon release by sensitized lymphocytes after stimulation with antigens from MT. Basically, the test uses the same principle as the TST (evaluation of the release of cytokines by sensitized lymphocytes). It needs a blood sampling, transportation and a laboratory equipment; it is more expensive than the TST but offers several advantages. The first and most important advantage is the fact that only 2 antigens from MTB (ESAT-6 and CFP-10), which are absent from M. bovis, BCG and most environmental mycobacteria, are used for stimulating the lymphocytes. Then, the test has a higher specificity. The second positive feature of the test is the standardization and objectivity of the procedure, without the subjective bias due to the injection technique and the reading of the skin reaction. Furthermore, the test is performed with a negative and positive control, thus decreasing the risk of error. The test can be repeated without the risk of boosting the result. Nevertheless, apart from cost and technical requirements, the performance of the test requires attention to several conditions, among which the transport conditions of the blood samples to the laboratory, the delay in processing, and the availability of a specialized laboratory (40).

Currently, two tests are available on the market (the QuantiFERON-TB Plus and the T-SPOT.TB test), which differ in the laboratory procedure but rely on the same principle.

QuantiFERON-TB Plus (QFT-Plus) is the new version of the QFT-Gold In-Tube. Compared to the QFT-Gold In-Tube, with antigens optimized to stimulate CD4+ T cells, QFT-Plus contains new antigens optimized for both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell stimulation (24). QFT-Plus has potential to indicate recent infection and disease activity. A recent meta-analysis has revealed that QFT-Plus is a more sensitive test compared to QFT-GIT for detecting M. tuberculosis infection (46).

The T-SPOT.TB is an enzyme-linked immunospot assay performed on separated and counted peripheral blood mononuclear cells, which include circulating monocytes and lymphocytes; it uses ESAT-6 and CFP-10 peptides. The result is reported as number of interferon-gamma-producing T cells (spot-forming cells in antigen wells minus negative control wells). An individual is considered positive for MT infection if the spot counts in the TB antigen wells exceed a specific threshold relative to the control wells (33). In general, IGRA results are reported as one of the following: positive, negative, indeterminate or uninterpretable results (some test manufacturers and laboratories add a borderline category for interpretable test results close to the cut-off).

Skin tests with specific Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens: C-TB and Diaskintest

Two skin tests (C-TB and Diaskintest) using only two specific MT antigens (ESAT-6 and CFP-10) instead of the tuberculin solution have recently been developed. They have a specificity similar to the IGRAs (no influence of prior BCG vaccination or environmental mycobacteria) but must be placed and read with a technique similar to the TST (intradermal injection, reading after 48-72 hours).

These tests seem to have performance similar to the IGRAs (2, 44, 47). None of the tests is currently available on the European market.

Comparison between available diagnostics for LTBI

Several studies have compared the performance of the TST and the IGRAs in adults and children (3, 18, 31). Globally, these studies confirm that the concordance is satisfactory in patients with active TB or patients with recent TB contact, but a large group of adults and children has discordant test results. The combination of positive TST and negative IGRA is frequently associated with prior vaccination with BCG or exposure to environmental mycobacteria (false-positive TST), whereas the combination of negative TST and positive IGRA is less frequent and may be attributed to a decrease in the reactivity of the immune system associated with very young or very old age or immmuno-depression (false-negative TST). The superior specificity of IGRAs compared with TST is demonstrated by the very low risk of TB development in subjects with a negative IGRA, independently of the TST result (4). The performance of the IGRA is satisfactory in children from the age of 2 years (10). Systematic performance of the IGRA in subjects with a low-risk of infection (e.g., routine annual testing in healthcare workers) gives rise to variations in test results, with apparent conversions and reversions, mostly due to variations around the cut-off (6).

The intensity of the reaction to TST and IGRA seems to be correlated with the risk of future TB (36, 54) but both tests have a low positive predictive value. The negative predictive value is high for both tests, but higher for the IGRA than for the TST (1).

A detailed comparison between the available diagnostic tests for LTBI infection is outlined in Table 2.

Table 2.

A comparison of available diagnostics for latent tuberculosis (TB) infection, adapted from Pai M, Sotgiu G. (41)

| Characteristic | *PPD-based tubercolin skin test | New specific skin test (under either development or validation) | IFN-γ release assays |

| Testing format | Intradermal skin test | Intradermal skin test (in vivo) | Ex vivo assay (ELISA or ELISPOT) |

| Antigens used | Purified protein derivate | ESAT-6 and CFP-10 | ESAT-6 and CFP-10 |

| Intended use | Screening for LTBI | Screening for LTBI | Screening for LTBI |

| Sensitivity | High | Modest | Modest |

| Sensitivity in immune-compromised population | Reduced | Reduced | Reduced |

| Specificity | Modest | High | High |

| Impact of BCG on specificity | High (when BCG is given after infancy or several times) | None | None |

| Ability to predict progression to active TB | Modest | Unknown (but likely modest based on indirect evidence from IGRAs) | Modest |

| Ability to resolve the various stages within the spectrum of M. Tuberculosis infection | Low | Low | Low |

* Purified Proteine Derivative

Table 1.

List of possible reasons accounting for tuberculin skin test (TST) misleading results

| FALSE POSITIVE REACTIONS | FALSE NEGATIVE REACTIONS |

| Infection with non-tuberculosis mycobacteria | Cutaneous anergy (inability to react to skin test because of weakened immune system) |

| Previous BCG vaccination | Recent TB infection (within 8-10 weeks of exposure) |

| Incorrect method administration | Ancient TB infection (many years) |

| Incorrect interpretation of reaction | Very young or very old age |

| Incorrect bottle of antigen used | Recent live-virus vaccination (e.g., measles and smallpox) |

| Overwhelming TB disease | |

| Some viral illnesses (e.g., measles and chicken pox) | |

| Incorrect method of administration | |

| Incorrect interpretation of reaction (intra- and inter-observer errors) |

With regard to LTBI diagnosis in high income and upper middle-income countries with estimated TB incidences less than 100 per 100,000 population, the current WHO Guidelines recommend that either a TST or an IGRA can be used to detect LTBI.

Future developments

The immunological sensitization induced by the contact with MTB is not limited to the release of Interferon-Gamma. Numerous other cytokines are released by several blood cells and can be measured in vitro (22).

An interesting study proved that the proportion of monocytes in blood and an elevated monocytes/lymphocytes ratio could be an indicator of the risk of development of TB after TB contact in patients with a positive TST (43).

Recently, several publications focused on the RNA gene signature or on the assessment of the genetic changes induced by mycobacteria. Such changes have also been observed after infection with other virus and bacteria (48). Changes seem to correlate with the infection and with the risk of developing TB, thus allowing to predict which infected persons will progress to TB (52, 57). Most tests use a combination of genetic markers to detect the infection and the risk of TB. The number of genetic changes assessed by diverse methods lies between 3 and 393 and the technology for their determination is still not available outside research laboratories. Currently, a 3-gene signature has been demonstrated as promising (53). A recent study assessed the diagnostic accuracy of several RNA sequencing tests in patients with symptoms compatible with pulmonary TB (50). Four of them met the minimum WHO requirements for a triage test but not for a confirmatory test.

Apart from blood tests, other tests may allow for the detection of the presence of living mycobacteria in the body before the emergence of active disease. A fascinating study by Esmail demonstrated that 2-deoxy-2-(18F) fluoro-d-glucose PET-CT (FDG-PET-CT) can detect living mycobacteria in the lung and lymph nodes of HIV-positive patients and predict the progression to TB (14).

Conclusion

LTBI is a complex and heterogeneous state resulting from the dynamic interaction between MT and the host’s immune response. Early identification and treatment of individuals with LTBI are priorities for TB control in specific groups at risk within the population: this is of crucial meaning in recently infected individuals both at the community level and in some occupational settings.

Screening for LTBI and proper preventive treatment are key-elements of the End TB strategy (53).

The currently available diagnostic methods for the diagnosis of LTBI are the “century-old” TST and, since 2005, the IGRA test. The IGRAs provide an opportunity for more targeted LTBI treatment than offered with TST, but the implementation of costly and laboratory-intensive IGRA testing remains limited or not available in many settings.

As there is no gold standard test, an improved understanding is needed in this field, also in order to develop better tools for diagnosing LTBI, distinguishing it from active TB, and predicting progression from LTBI to clinical disease (23).

Conflict of Interest:

JPZ has received speaker’s fees from Qiagen for medical training courses.

GS has no financial and competing interests.

MC has no financial and competing interests.

PD has participated at Workshops of the National Congresses of the Associazione Microbiologici Clinici Italiani - AMCLI sponsored by Diasorin and at scientific and advisory board meetings sponsored by Sanofi.

MC, PD and MC are members of the Working Group on Tuberculosis of the Italian Society of Occupational Medicine (Società Italiana di Medicina del Lavoro - SIML).

La diagnosi dell’infezione tubercolare latente (ITBL): test attualmente disponibili, sviluppi futuri e prospettive per l’eliminazione della tubercolosi (TB)

Introduzione

Nonostante i grandi sforzi compiuti, la tubercolosi (TB) è ancora una delle principali minacce per la salute pubblica in tutto il mondo, con 10 milioni di nuovi casi e 1,2 milioni di decessi nel 2018. Si stima che un quarto della popolazione globale (circa 2 miliardi di persone) sia infetto dal Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MT), incluse approssimativamente circa 13 milioni di persone negli Stati Uniti.

La maggior parte degli individui infetti è asintomatica ed è classificata con la condizione d’infezione tubercolare latente (ITBL). L’ITBL è definita dall’Organizzazione Mondiale della Sanità (OMS) come uno stato di risposta immunitaria persistente agli antigeni del MT, senza evidenza di tubercolosi attiva clinicamente manifesta: quindi, questa condizione identifica gli individui che sono stati in contatto con il MT e hanno sviluppato una risposta immunitaria, ma questo non implica necessariamente la persistenza di patogeni viventi nell’organismo umano. La stragrande maggioranza degli individui infetti non presenta segni o sintomi di TB e non svilupperà mai la malattia.

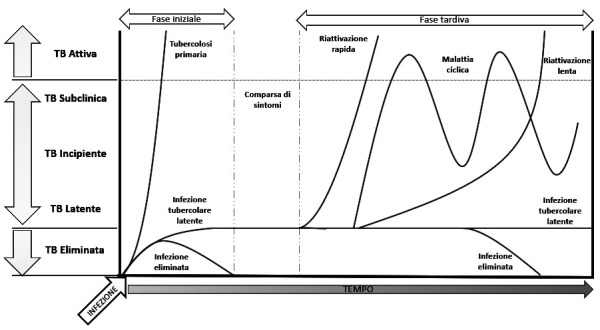

Il rischio di sviluppare la TB attiva dopo l’infezione dipende dall’età, dalla qualità dei meccanismi di difesa immunitaria e dal tempo trascorso dall’infezione. Il rischio stimato life-time è del 5-10%, ma è maggiore nei bambini piccoli, negli individui immunocompromessi e nel breve periodo (entro 1-2 anni) dopo un contatto con un caso di TB contagiosa. L’ITBL non è una condizione stabile: episodi intermittenti, transitori o progressivi di replicazione micobatterica possono portare a tubercolosi incipiente, quindi subclinica e, infine, clinicamente attiva (Fig. 1).

Figura 1.

La storia naturale della malattia tubercolare: vie di progressione; adattata da Drain et al.

Nei paesi ad alto reddito, l’incidenza di TB attiva ha continuato a diminuire negli ultimi decenni, ma la prevalenza dell’LTBI è rimasta stabile.

Per decenni, i programmi di controllo della tubercolosi si sono concentrati quasi esclusivamente sui casi di TB contagiosa. La ricerca proattiva dei casi e la corretta gestione della TB attiva dovrebbero essere la priorità assoluta per i programmi di controllo. Tuttavia, è evidente che questa strategia da sola non può permettere il raggiungimento dell’eliminazione della TB. Questo importante obiettivo può essere raggiunto attraverso strategie globali mirate a un’appropriata gestione integrata dell’ITBL e della TB attiva. Infatti, poiché la maggior parte dei nuovi casi di TB è il risultato della riattivazione di ITBL acquisita nel passato piuttosto che di una recente infezione, l’intensificazione delle strategie di screening e di trattamento dell’ITBL è riconosciuta come una componente cruciale per l’eliminazione della TB, specialmente in contesti a bassa prevalenza di TB. L’ITBL rappresenta un grande serbatoio di TB attiva, con la progressione da casi di ITBL non trattati responsabile di circa l’80% dei casi di TB negli Stati Uniti.

Il piano d’azione dell’OMS per l’eliminazione della TB nei paesi a bassa incidenza (definiti come quelli con un tasso di notifica di TB <100 casi di TB - tutte le forme - per milione di popolazione) ha messo in evidenza il ruolo di sanità pubblica dello screening per la TB attiva e l’LTBI nei contatti di casi contagiosi. Una delle azioni prioritarie nei paesi a bassa incidenza di TB è l’identificazione dei casi contagiosi per implementare il contact tracing e prevenire nuovi casi incidenti di TB attiva.

La diagnosi precoce di ITBL dopo un’esposizione documentata o sospetta è fondamentale per valutare il rischio di tubercolosi attiva e offrire un tempestivo trattamento a scopo preventivo. Pertanto, al fine di eliminare la TB nei paesi a bassa incidenza è necessario individuare i gruppi a maggior rischio di sviluppare la malattia sia a livello di comunità sia a livello occupazionale.

È stato descritto come la trasmissione del MT sia più probabile in alcuni ambienti confinati come strutture sanitarie, strutture di assistenza a lungo termine, strutture ad alta densità abitativa (es., rifugi per senzatetto, carceri, scuole) con un rischio maggiore per i pazienti, i residenti e i lavoratori. In effetti, ciò vale nelle strutture carcerarie sia per ITBL sia per TB, così come in altri congregate settings per richiedenti asilo e migranti provenienti da paesi ad alta incidenza di TB. Cattive condizioni igieniche, scarsa ventilazione e alta densità di ospiti e lavoratori contagiosi potrebbero spiegare l’aumentato rischio di trasmissione del MT in questi contesti.

I medici del lavoro e gli specialisti in medicina preventiva possono svolgere un ruolo chiave nell’implementazione di programmi di sorveglianza dell’ITBL, diagnosi precoce e terapia preventiva in categorie e individui a maggior rischio rispetto alla popolazione generale di essere esposti al MT e/o di sviluppare la TB attiva. In questa prospettiva, la valutazione del rischio TB nel contesto occupazionale deve focalizzare i seguenti item: (I) epidemiologia locale e condizioni dell’ambiente di lavoro (es., contesti sanitari e specifici congregate settings); (II) procedure mediche ad alto rischio (es., broncoscopia, riabilitazione respiratoria); e (III) fattori di rischio individuali associati alla progressione da ITBL a malattia attiva (es., comorbosità, immunodepressione iatrogena).

Il presente documento riassume brevemente le recenti conoscenze acquisite sull’ITBL e gli attuali strumenti diagnostici disponibili, riportando anche gli sviluppi futuri e le sfide per la diagnosi. Una migliore conoscenza e comprensione dei test diagnostici disponibili per la diagnosi dell’ITBL, compresi i loro punti di forza e limiti, nonché la loro applicabilità nei diversi contesti e categorie di soggetti, può contribuire a identificare e gestire appropriatamente questa condizione al fine di eliminare la TB.

Test disponibili per ITBL

Al momento non esiste alcun test per l’identificazione diretta dell’infezione da MT vivente nell’uomo.

La diagnosi dell’ITBL è indiretta e si basa sul rilevamento di una risposta immunitaria contro gli antigeni del MT, partendo dal presupposto che la risposta immunitaria si sia sviluppata a seguito di un contatto con il MT. I test cutanei alla tubercolina (TST) e quelli basati sul rilascio d’interferone gamma (IGRAs) sono i principali test diagnostici per l’ITBL: entrambi sono test indiretti basati sulla risposta immunitaria alla TB e non valutano direttamente la presenza o la vitalità dei bacilli di TB.

Inoltre, non sono attualmente disponibili test che consentano la distinzione tra risposta immunitaria indotta dall’ITBL e dalla TB attiva.

Pertanto, la distinzione tra ITBL e TB attiva si basa su criteri clinici, batteriologici e radiologici.

Gli attuali test diagnostici disponibili per ITBL sono riportati e discussi di seguito.

Il tuberculin skin test (TST)

Il test classico per la rilevazione dell’ITBL è il TST, il più antico test diagnostico ancora in uso in medicina, che si basa sulla reazione diretta contro gli antigeni del MT iniettati nel derma della cute. L’intensità della reazione infiammatoria locale dovuta al rilascio di citochine da parte dei linfociti sensibilizzati è misurata dopo 48-72 ore ed è stata dimostrata da alcuni autori essere correlata al rischio di sviluppare la TB.

Il TST è economico, può essere eseguito ovunque da qualsiasi operatore sanitario con adeguata formazione senza la necessità di attrezzature tecniche, a eccezione di una catena del freddo per la conservazione della soluzione di tubercolina. Tuttavia, il test è caratterizzato da un gran numero di limiti che ne rendono l’utilizzo lontano dall’ideale. Inoltre, la soluzione di tubercolina contiene un gran numero di antigeni (~ 200), la maggior parte dei quali sono comuni a M. tuberculosis, M. bovis BCG e micobatteri ambientali: una reazione positiva può, quindi, essere causata da una precedente vaccinazione con BCG o da un contatto con micobatteri ambientali e possiede una bassa specificità. Inoltre, la tecnica per l’iniezione della tubercolina e quella della lettura della reazione possono essere associate a diversi errori tecnici (es., iniezione in uno strato cutaneo errato, fuoriuscita della soluzione, valutazione soggettiva della reazione cutanea con errori intra e inter-osservatore). Diverse condizioni possono ridurre la reattività cutanea, come infezioni virali, immunodepressione, giovane età e senescenza (Tab.1). La ripetizione del test può provocare un aumento artificiale delle dimensioni della seconda reazione (il cosiddetto “effetto booster”). Inoltre, il test viene eseguito senza alcun controllo positivo o negativo e anche la qualità della tubercolina può influenzare la percentuale di reazioni interpretate come positive.

Un altro svantaggio è il limitato valore predittivo per la progressione a malattia tubercolare. In altre parole, la maggior parte dei soggetti con risultati TST positivi non progredisce verso la malattia attiva, quindi, risulta inevitabile una sovrastima dei soggetti a cui offrire il trattamento, poiché non c’è modo di sapere quale individuo con risultato TST positivo trarrà effettivamente beneficio dalla terapia preventiva per ITBL. Nonostante questi limiti, la pronta identificazione di una cuti-conversione al TST, nel breve periodo dopo un contatto con un caso infettivo, dovrebbe orientare l’indicazione al trattamento preventivo.

Interferon Gamma Release Assays (IGRAs)

Un test alternativo è quello su sangue che si basa sulla misurazione in vitro del rilascio di gamma-interferone da parte dei linfociti sensibilizzati dopo la stimolazione con antigeni di MT. Fondamentalmente, il test utilizza lo stesso principio del TST (valutazione del rilascio di citochine da parte dei linfociti sensibilizzati). Richiede un prelievo di sangue, il trasporto dei campioni e attrezzature di laboratorio; è più costoso del TST ma offre numerosi vantaggi. Il primo e più importante vantaggio è il fatto che solo 2 antigeni del MT (ESAT-6 e CFP-10), che sono assenti in M. bovis, BCG e nella maggior parte dei micobatteri ambientali, vengono utilizzati per stimolare i linfociti. Quindi, il test ha una specificità più elevata. La seconda caratteristica positiva del test è la standardizzazione e l’obiettività della procedura, senza distorsioni soggettive dovute alla tecnica di iniezione e alla lettura della reazione cutanea. Inoltre, il test prevede un controllo negativo e positivo, riducendo così il rischio di errore. Il test può essere ripetuto senza il rischio di incorrere nell’effetto booster. Tuttavia, a parte i costi e i requisiti tecnici, l’esecuzione del test richiede attenzione su diversi aspetti, tra cui le condizioni di trasporto dei campioni di sangue al laboratorio, l’eventuale ritardo di processazione e la disponibilità di un laboratorio specializzato.

Attualmente sono disponibili sul mercato due test (QuantiFERON-TB Plus e T-SPOT.TB), che differiscono nelle procedure di laboratorio ma si basano sullo stesso principio.

QuantiFERON-TB Plus (QFT-Plus) è la nuova versione del QFT-Gold In-Tube. Rispetto alla QFT-Gold In-Tube, con antigeni ottimizzati per stimolare le cellule T CD4 +, QFT-Plus contiene nuovi antigeni ottimizzati per la stimolazione delle cellule T CD4 + e CD8 +. QFT-Plus ha il potenziale d’indicare una recente infezione e lo stato di attività della malattia. Una recente meta-analisi ha riportato come che QFT-Plus sia più sensibile rispetto a QFT-GIT per la rilevazione dell’infezione da MT.

Il T-SPOT.TB è un test enzyme-linked immunospot assay eseguito su cellule mononucleate di sangue periferico separate e contate, che includono monociti e linfociti circolanti; utilizza peptidi ESAT-6 e CFP-10. Il risultato è riportato come numero di cellule T che producono interferone-gamma (differenza tra cellule che formano spot nei pozzetti con antigene rispetto a quelle del controllo negativo). Un individuo è considerato positivo per l’infezione da MT se il conteggio degli spot nei pozzetti dell’antigene TB supera una soglia specifica rispetto ai pozzetti di controllo. In generale, i risultati IGRA sono riportati come uno dei seguenti: risultati positivi, negativi, indeterminati o non interpretabili (alcuni produttori e laboratori di test aggiungono una categoria border-line per l’interpretazione dei risultati vicino al cut-off).

Test cutanei con antigeni specifici di Mycobacterium tuberculosis: C-TB e Diaskintest

Recentemente sono stati sviluppati due test cutanei (C-TB e Diaskintest) che utilizzano solo due antigeni specifici di MT (ESAT-6 e CFP-10) invece della soluzione di tubercolina. Hanno una specificità simile agli IGRAs (nessuna influenza da parte della precedente vaccinazione BCG o di micobatteri ambientali) ma devono essere posizionati e letti con una tecnica simile al TST (iniezione intradermica, lettura dopo 48-72 ore).

Questi test sembrano avere prestazioni simili agli IGRAs. Nessuno di questi test è attualmente disponibile sul mercato europeo.

Confronto tra test diagnostici disponibili per ITBL

Diversi studi hanno confrontato le prestazioni del TST e degli IGRAs negli adulti e nei bambini. A livello globale, questi studi confermano che la concordanza è soddisfacente nei pazienti con TB attiva o in pazienti con recenti contatti TB, ma un ampio gruppo di soggetti adulti e bambini ha riportato risultati discordanti. La combinazione di TST positivo e IGRA negativo è frequentemente associata a una precedente vaccinazione con BCG o all’esposizione a micobatteri ambientali (TST falso positivo), mentre la combinazione di TST negativo e IGRA positivo è meno frequente e può essere attribuita a una diminuzione della reattività del sistema immunitario associato a età molto giovani o avanzate o a immunodepressione (TST falso negativo). La specificità superiore degli IGRA rispetto al TST è dimostrata dal bassissimo rischio di sviluppo della TB in soggetti con IGRA negativo, indipendentemente dal risultato del TST. Le prestazioni dell’IGRA sono soddisfacenti nei bambini dall’età di 2 anni. La performance sistematica dell’IGRA in soggetti a basso rischio d’infezione (es., test annuali di routine negli operatori sanitari) porta a variazioni nei risultati del test, con apparenti conversioni e reversioni, principalmente dovute a variazioni intorno al cut-off.

L’intensità della reazione a TST e IGRA sembra essere correlata al rischio di TB futuro ma entrambi i test hanno un basso valore predittivo positivo. Il valore predittivo negativo è elevato per entrambi i test, risultando superiore per IGRA rispetto a TST.

Un confronto dettagliato tra i test diagnostici disponibili per ITBL è riportato nella Tabella 2.

Tabella 2.

Comparazione tra i test diagnostici disponibili per Infezione tubercolare latente, adattata da Pai M, Sotgiu G.

| Caratteristica | TST | Nuovi test cutanei specifici | IGRAs |

| Formato del test | Test cutaneo intradermico | Test cutaneo intradermico (in vivo) | Ex vivo assay (ELISA o ELISPOT) |

| Antigeni utilizzati | Derivato proteico purificato | ESAT-6 e CFP-10 | ESAT-6 e CFP-10 |

| Destinazione d’uso | Screening per ITBL | Screening per ITBL | Screening per ITBL |

| Sensibilità | Alta | Modesta | Modesta |

| Sensibilità nella popolazione immuno-compromessa | Ridotta | Ridotta | Ridotta |

| Specificità | Modesta | Alta | Alta |

| Impatto del BCG sulla specificità | Alta (quando il BCG viene somministrato dopo l’infanzia o più volte) | Nessuno | Nessuno |

| Capacità di prevedere la progressione verso TB attiva | Modesta | Sconosciuta (ma probabilmente modesta in base a evidenza indiretta ottenuta con IGRAs) | Modesta |

| Capacità di definire le varie fasi nello spettro dell’infezione da MT | Bassa | Bassa | Bassa |

Tabella 1.

Elenco dei possibili motivi di una non corretta interpretazione dei risultati del test cutaneo alla tubercolina (TST)

| Reazioni false positive | Reazioni false negative |

| Infezione da micobatteri non tubercolari | Anergia cutanea (incapacità di reazione al test cutaneo a caua d’immunocomprosissione) |

| Pregressa vaccinazione con BCG | Infezione da TB recente (entro 8-10 settimane dall’esposizione) |

| Errata tecnica di somministrazione | Infezione da TB pregressa (molti anni) |

| Interpretazione errata della reazione | Fasce estreme di età (molto giovane e avanzata) |

| Utilizzo di flacone di antigene errato | Recente vaccinazione con virus vivente attenuato (es., morbillo e vaiolo) |

| Malattia tubercolare diffusa | |

| Alcune malattie virali (es., morbillo e varicella) | |

| Errata tecnica di somministrazione | |

| Interpretazione errata della reazione (errori intra e inter-osservatore) |

Per quanto riguarda la diagnosi d’ITBL in paesi ad alto e medio-alto reddito, con incidenza stimata di TB inferiore a 100 casi per 100.000 abitanti, le attuali Linee Guida dell’OMS raccomandano come un TST o un test IGRA possano essere utilizzati per identificare l’ITBL.

Sviluppi futuri

La sensibilizzazione immunologica indotta dal contatto con MT non si limita al rilascio di Interferone-Gamma. Numerose altre citochine vengono rilasciate da diverse cellule del sangue e possono essere misurate in vitro.

Uno studio interessante ha dimostrato che la proporzione di monociti nel sangue e un elevato rapporto monociti/linfociti potrebbe essere un indicatore del rischio di sviluppo di TB dopo contatto con TB in pazienti con TST positivo.

Recentemente, diverse pubblicazioni si sono concentrate sulla RNA gene signature o sulla valutazione delle modificazioni genetiche indotte dai MT. Tali cambiamenti sono stati osservati anche dopo l’infezione con altri virus e batteri. I cambiamenti sembrano essere correlati con l’infezione e con il rischio di sviluppare la TB, permettendo così di prevedere quali soggetti infetti possano progredire a malattia. La maggior parte dei test utilizza una combinazione di marcatori genetici per rilevare l’infezione e il rischio di TB. Il numero di cambiamenti genetici valutati con metodi diversi è compreso tra 3 e 393 e la tecnologia per la loro determinazione non è ancora disponibile al di fuori dei laboratori di ricerca. Attualmente, una 3-gene signature è stata dimostrata promettente. Un recente studio ha valutato l’accuratezza diagnostica di numerosi test di sequenziamento dell’RNA in pazienti con sintomi compatibili con TB polmonare. Quattro di loro hanno soddisfatto i requisiti minimi dell’OMS previsti per test di triage ma non per test di conferma.

Oltre agli esami del sangue, altri test possono consentire di rilevare la presenza di micobatteri viventi nell’organismo prima della comparsa della malattia attiva. Un affascinante studio di Esmail ha dimostrato che la PET-CT al fluoro-d-glucosio 2-desossi-2- (18F) (FDG-PET-CT) può rilevare i micobatteri viventi nel polmone e nei linfonodi di pazienti HIV-sieropositivi e predire la progressione a TB.

Conclusioni

L’ITBL è uno stato complesso ed eterogeneo derivante dall’interazione dinamica tra il MT e la risposta immunitaria dell’ospite. La tempestiva identificazione e il trattamento precoce degli individui con ITBL costituiscono una priorità per il controllo della TB in gruppi specifici a rischio all’interno della popolazione: ciò assume un’importanza fondamentale nei soggetti recentemente infettati sia a livello di comunità sia in alcuni contesti occupazionali.

Lo screening e l’appropriato trattamento preventivo dell’ITBL sono elementi chiave della strategia “End TB”.

I metodi diagnostici attualmente disponibili per la diagnosi dell’ITBL sono il “secolare” TST e, a partire dal 2005, il test IGRA. Gli IGRAs offrono l’opportunità di un trattamento dell’ITBL più mirato rispetto a quanto offerto dal TST, ma l’implementazione di questi test su sangue rimane limitata o non percorribile in molti contesti a causa dei costi e della necessità di laboratori specializzati.

Poiché non esiste un test gold-standard, risulta necessario migliore le conoscenze in questo campo, anche al fine di sviluppare migliori strumenti di diagnosi dell’ITBL, con possibilità di distinzione dalla TB attiva e con capacità di predire la progressione della stessa a malattia attiva.

References

- 1.Abubakar I, Drobniewski F, Southern J, et al. Prognostic value of interferon-gamma release assays and tuberculin skin test in predicting the development of active tuberculosis (UK PREDICT TB): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30355-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aggerbeck H, Ruhwald M, Hoff ST, et al. C-Tb skin test to diagnose Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in children and HIV-infected adults: A phase 3 trial. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0204554. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed A, Feng PI, Gaensbauer JT, et al. Interferon-gamma Release Assays in Children <15 Years of Age. Pediatrics. 2020;145(1):e20191930. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altet N, Dominguez J, Souza-Galvão ML, et al. Predicting the Development of Tuberculosis with the Tuberculin Skin Test and QuantiFERON Testing. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:680–688. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201408-394OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bamrah S, Yelk Woodruff RS, Powell K, et al. Tuberculosis among the homeless, United States, 1994-2010. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17:1414–1419. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.13.0270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banaei N, Gaur RL, Pai M. Interferon Gamma Release Assays for Latent Tuberculosis: What Are the Sources of Variability. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:845–850. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02803-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Binswanger IA, O’Brien K, Benton K, et al. Tuberculosis testing in correctional officers: a national random survey of jails in the United States. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:464–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bozorgmehr K, Razum O, Saure D, et al. Yield of active screening for tuberculosis among asylum seekers in Germany: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Euro Surveill. 2017;22:30491. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.12.30491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CDC - Epidemiology of Tuberculosis in Correctional Facilities, United States, 1993-2017 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiappini E, Storelli F, Tersigni C, et al. QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube test performance in a large pediatric population investigated for suspected tuberculosis infection. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2019;32:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2019.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen A, Mathiasen VD, Schön T, et al. The global prevalence of latent tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2019;54(3):1900655. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00655-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dara M, Solovic I, Sotgiu G, et al. Tuberculosis care among refugees arriving in Europe: a ERS/WHO Europe Region survey of current practices. Eur Respir J. 2016;48:808–817. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00840-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drain PK, Bajema KL, Dowdy D, et al. Incipient and Subclinical Tuberculosis: a Clinical Review of Early Stages and Progression of Infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2018;31(4):e00021–18. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00021-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esmail H, Lai RP, Lesosky M, et al. Characterization of progressive HIV-associated tuberculosis using 2-deoxy-2-(18F)fluoro-D-glucose positron emission and computed tomography. Nat Med. 2016;22:1090–1093. doi: 10.1038/nm.4161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Stockholm: ECDC; 2016. Guidance on tuberculosis control in vulnerable and hard-to-reach populations. [Google Scholar]

- 16.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Stockholm: ECDC; 2017. Systematic review on the diagnosis, treatment, care and prevention of tuberculosis in prison settings. [Google Scholar]

- 17.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control/WHO Regional Office for Europe. Tuberculosis surveillance and monitoring in Europe 2020 – 2018 data. Stockholm: ECDC [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gualano G, Mencarini P, Lauria FN, et al. Tuberculin skin test - Outdated or still useful for Latent TB infection screening. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;80S:S20–S22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Houben RM, Dodd PJ. The Global Burden of Latent Tuberculosis Infection: A Re-estimation Using Mathematical Modelling. PLoS Med. 2016;13(10):e1002152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huebner RE, Schein MF, Bass JB., Jr The tuberculin skin test. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:968–975. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.6.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Isler MA, Rivest P, Mason J, Brassard P. Screening employees of services for homeless individuals in Montréal for tuberculosis infection. J Infect Public Health. 2013;6:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamakia R, Kiazyk S, Waruk J, et al. Potential biomarkers associated with discrimination between latent and active pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;21:278–285. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.16.0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kik SV, Schumacher S, Cirillo DM, et al. An evaluation framework for new tests that predict progression from tuberculosis infection to clinical disease. Eur Respir J. 2018;52(4):1800946. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00946-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim SH, Jo KW, Shim TS. QuantiFERON-TB Gold PLUS versus QuantiFERON- TB Gold In-Tube test for diagnosing tuberculosis infection. Korean J Intern Med. 2020;35:383–391. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2019.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kunst H, Burman M, Arnesen TM, et al. Tuberculosis and latent tuberculous infection screening of migrants in Europe: comparative analysis of policies, surveillance systems and results. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;21:840–851. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.17.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lambert LA, Armstrong LR, Lobato MN, et al. Tuberculosis in Jails and Prisons: United States, 2002-2013. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:2231–2237. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lo Bue PA, Mermin JH. Latent tuberculosis infection: the final frontier of tuberculosis elimination in the USA. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(10):e327–e333. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30248-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lönnroth K, Migliori GB, Abubakar I, et al. Towards tuberculosis elimination: an action framework for low-incidence countries. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:928–952. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00214014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lönnroth K, Mor Z, Erkens C, et al. Tuberculosis in migrants in low-incidence countries: epidemiology and intervention entry points. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;21:624–637. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.16.0845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mack U, Migliori GB, Sester M, et al. LTBI: latent tuberculosis infection or lasting immune responses to M. tuberculosis? A TBNET consensus statement. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:956–973. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00120908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mancuso JD, Mazurek GH, Tribble D, et al. Discordance among commercially available diagnostics for latent tuberculosis infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:427–434. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201107-1244OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matteelli A, Rendon A, Tiberi S, et al. Tuberculosis elimination: where are we now. Eur Respir Rev. 2018;27(148):180035. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0035-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Menzies D. Use of interferon-gamma release assays for diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection (tuberculosis screening) in adults. Uptodate 2020. Available on line at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/use-of-interferon-gamma-release-assays-for-diagnosis-of-latent-tuberculosis-infection-tuberculosis-screening-in-adults. (last accessed 27-05-2000) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menzies D. Interpretation of repeated tuberculin tests. Boosting, conversion, and reversion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:5–21. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9801120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miramontes R, Hill AN, Yelk Woodruff RS, et al. Tuberculosis infection in the United States: prevalence estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2012. PLoS One. 2015 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitchell CS, Gershon RR, Lears MK, et al. Risk of tuberculosis in correctional healthcare workers. J Occup Environ Med. 2005;47:580–586. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000161738.88347.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moffa M, Cronk R, Fejfar D, et al. A systematic scoping review of environmental health conditions and hygiene behaviors in homeless shelters. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2019;222:335–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2018.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morán-Mendoza O, Marion SA, Elwood K, et al. Tuberculin skin test size and risk of tuberculosis development: a large population-based study in contacts. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11:1014–1020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mulder C, Erkens C, Kouw P, et al. Tuberculin skin test reaction depends on type of purified protein derivative: implications for cut-off values. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2019;23:1327–1334. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.18.0838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pai M, Denkinger CM, Kik SV, et al. Gamma interferon release assays for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:3–20. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00034-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pai M, Sotgiu G. Diagnostics for latent TB infection: incremental, not transformative progress. Eur Respir J. 2016;47:704–706. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01910-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Placidi D, Tonozzi B, Alessio L, et al. (Tuberculin skin test (TST) survey among healthcare workers (HCWs) in hospital: a systematic review of the literature) G Ital Med Lav Ergon. 2007;29(3 Suppl):409–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rakotosamimanana N, Richard V, Raharimanga V, et al. Biomarkers for risk of developing active tuberculosis in contacts of TB patients: a prospective cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2015;46:1095–1103. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00263-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ruhwald M, Aggerbeck H, Gallardo RV, et al. Safety and efficacy of the C-Tb skin test to diagnose Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, compared with an interferon gamma release assay and the tuberculin skin test: a phase 3, double-blind, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5:259–268. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30436-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scotto G, Fazio V, Lo Muzio L. Tuberculosis in the immigrant population in Italy: state-of-the-art review. Infez Med. 2017;25:199–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sotgiu G, Saderi L, Petruccioli E, et al. QuantiFERON TB Gold Plus for the diagnosis of tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2019;79:444–453. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2019.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Starshinova A, Zhuravlev V, Dovgaluk I, et al. A comparison of intradermal test with recombinant tuberculosis allergen (diaskintest) with other immunologic tests in the diagnosis of tuberculosis infection. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2018;7:32–39. doi: 10.4103/ijmy.ijmy_17_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sweeney TE, Wong HR, Khatri P. Robust classification of bacterial and viral infections via integrated host gene expression diagnostics. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(346):346ra91. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf7165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tissot F, Zanetti G, Francioli P, et al. Influence of bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccination on size of tuberculin skin test reaction: to what size. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:211–217. doi: 10.1086/426434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Turner CT, Gupta RK, Tsaliki E, et al. Blood transcriptional biomarkers for active pulmonary tuberculosis in a high-burden setting: a prospective, observational, diagnostic accuracy study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:407–419. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30469-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uden L, Barber E, Ford N, et al. Risk of Tuberculosis Infection and Disease for Health Care Workers: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4(3):ofx137. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Warsinske H, Vashisht R, Khatri P. Host-response-based gene signatures for tuberculosis diagnosis: A systematic comparison of 16 signatures. PLoS Med. 2019;16(4):e1002786. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Warsinske HC, Rao AM, Moreira FMF, et al. Assessment of Validity of a Blood-Based 3-Gene Signature Score for Progression and Diagnosis of Tuberculosis, Disease Severity, and Treatment Response. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(6):e183779. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Winje BA, White R, Syre H, et al. Stratification by interferon-gamma release assay level predicts risk of incident TB. Thorax. 2018 doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-211147. thoraxjnl-2017-211147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.World Health Organization. Towards tuberculosis elimination: an action framework for low-incidence countries. WHO 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2019 (Internet). Geneva (CH): World Health Organization 2018. Available on line at: https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/ (last accessed 27-05-2000) [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zak DE, Penn-Nicholson A, Scriba TJ, et al. A blood RNA signature for tuberculosis disease risk: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2016;387:2312–2322. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01316-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]