Abstract

Introduction:

In the European Union, the employment rate for the population in the age group 55-64 years has greatly increased in the last two decades. Companies, especially in sectors such as banking, are looking for new strategies to improve the productivity of workers in this age group.

Objectives:

This study was conceived with the purpose of exploring the associations between job characteristics that could influence stress and certain organizational aspects in a large population of banking workers.

Methods:

More than 2,000 workers over 50 years of age of an Italian banking group participated in the study. Work-related stress was measured with the Stress Questionnaire (SQ). Organizational aspects of work were measured with a dedicated scale included in the SQ. Demographic aspects were detected by specific questions. Structural equation modelling was used and correlation coefficients were calculated.

Results:

The results from the structural equation modeling supported the theoretical model. Organizational policies are associated with both stress correlated factors (β=0.468) and perceptions of supervisor support and social support (β=0.710). The perception of both parameters is associated with stress outcomes (β=0.365). The proposed model offered better results than a competitive model, on which a total mediation was tested, rather than a partial one (p<0.001).

Conclusions:

The results highlight the importance of an integrated assessment of the effects of organizational aspects of work and stress factors to implement the protection of physical and mental health. Further research will help to understand more thoroughly if the issues emerged are effectively related to age. This can be assessed through a case-control study that also includes younger workers.

Key words: Work-related stress, ageing, banking sector

Abstract

«Stress lavoro-correlato nel settore bancario: studio su una popolazione italiana anziana di oltre 2.000 lavoratori».

Introduzione:

Nell’Unione Europea, il tasso di occupazione della popolazione nella fascia di età 55-64 anni è notevolmente aumentato negli ultimi due decenni. In un simile contesto, le aziende – particolarmente in certi settori quali quello bancario – hanno oggi l’esigenza di implementare misure di supporto specifico per i lavoratori in tale fascia di età.

Obiettivi:

Questo studio è stato concepito con l’obiettivo di indagare le associazioni tra le caratteristiche del lavoro che potrebbero influenzare lo stress e determinati aspetti organizzativi in un’ampia popolazione di lavoratori bancari ultracinquantenni.

Metodi:

Hanno partecipato allo studio più di 2.000 lavoratori ultracinquantenni di un gruppo bancario italiano. Lo stress lavoro-correlato è stato misurato con lo Stress Questionnaire (SQ), il quale prende in considerazione diverse variabili psicosociali di interesse occupazionale e contiene una scala per la valutazione degli aspetti organizzativi. Utilizzando modelli di equazioni strutturali sono stati calcolati i coefficienti di correlazione.

Risultati:

I risultati del modello ad equazioni strutturali ha supportato il modello teorico. Le politiche organizzative sono risultate associate sia a fattori correlati allo stress (β=0.468) sia alla percezione del supporto dei supervisori e del supporto sociale (β=0.710). La percezione di entrambi i parametri è risultata associata ai risultati dello stress (β=0.365). Il modello proposto ha offerto risultati più affidabili rispetto ad un modello competitivo.

Conclusioni:

I risultati di questo studio evidenziano l’importanza di una valutazione integrata degli effetti degli aspetti organizzativi e degli stressors al fine di implementare la tutela della salute, fisica e psichica, nelle banche e, più in generale, negli ambienti di lavoro. Ulteriori ricerche potranno consentire di comprendere più a fondo se gli aspetti emersi siano effettivamente correlate all’età. Ciò potrà essere valutato mediante uno studio caso-controllo che includa anche lavoratori più giovani.

Introduction

Ageing workforce and work-related stress are two of the most current and challenging topics regarding health and safety (H&S) management at workplaces. In the European Union (EU), the employment rate for the population in the age group 55-64 years has increased from 38.4% in 2002 to 53.3% in 2015 (15). Population aging requires specific strengthening of health promotion programs and strategies to improve quality of life.

The percentage of older workers in the labor market is constantly growing and, consequently, organizations must allow them to continue working through specific support measures (12, 24, 36). Older workers represent a precious resource for organizations and society, for their knowledge and their cultural background (14, 32, 43). Strategic thinking, wisdom and problem-solving skills improve with age. Recent data show that older workers have lower rates of absenteeism and tend to be particularly loyal to their employers (27, 31, 46).

Work experience is compensating for the physiological age-related decline of cognitive processes (e.g. working memory and psychomotor functions) (7). An interesting mechanism is Selection, Optimization, and Compensation (SOC), a successful aging model that focuses not on outcomes but on the individual processes in order to maximize gains and minimize losses in response to everyday demands and functional decline in later life (2, 30). The Socio-Economic Status (SES) is another important aspect of the individual’s environment, which estimates access to material resources and social prestige. Literature findings provide evidence that SES relates to the brain’s functional network organization and anatomy across adult middle age, and that higher SES may be a protective factor against age-related brain decline (8, 9).

Viotti et al. (52), in a study among female kindergarten teachers aged 50 and over, showed that work ability can be appropriately considered a crucial resource, which can affect workers’ health and well-being by supporting workers to deal with job demands and optimally use job resources. From a practical point of view, the findings suggest that organizations should implement monitoring actions and intervention programs aimed at fine-tuning job demands and resources over the entire work life. This can promote the conservation of work ability and, thus, sustain workers’ well-being into the latter stages of their careers.

Nevertheless, the literature shows that older workers are perceived as less creative, less interested in new technologies, less integrated into the work teams and even less emotionally resilient (6, 10, 23, 42).

The banking sector is experiencing a particular moment by virtue of the changes in work organizations due to the global economic crisis (11, 16, 40, 50). In Italy, the main reason for the reorganization of the sector lies in the significant number of mergers and acquisitions. First, the rising integration of the domestic banking system, strongly encouraged by European economics authorities, has led to the creation of new large companies able to compete with the main international banking groups. In addition, reorganization was achieved accomplishing new banking alliances groups, with the consequent acquisition of a dominant position by only three large groups in the domestic market (21, 40). In the scenario described above, an aging workforce deserves special attention: support at work from colleagues and employers, and comfortable interpersonal relationships among colleagues and between employers and employees become even more important in the presence of changes in organizations (54).

To date, studies on aged banking workers have investigated work-related stress and its consequences on health (burnout, depression, etc.) in relation to demographic and occupational variables. Valente et al. (51) observed that the total number of years worked was associated with major depressive symptoms. The results of this study revealed that working in the banking sector required a constant updating of skills to deal with new models of work organization and that could arise in additional stress for employees, especially if older (26).

Amigo et al. (1) noticed that banking employees under the age of 35 and with a seniority of less than 10 years, had significantly higher scores in terms of professional efficiency than the older colleagues. This may be a consequence not only of the impulse and enthusiasm for the job, that usually younger people have, but also and above all of their better informatics skills.

Petarli et al. (38) argued that the continuous introduction of new technologies and the parallel recruitment of new workforce in the banking sector resulted in a sort of de-qualification of employees with greater seniority, who found significant criticalities in adapting to the growing computerization and the consequent reorganization of work. This condition made older employees more susceptible to stress.

The role of supervisor support and of social support is essential to avoid the negative perception of organizational policies and maintain a collaborative climate. Difficult relationships between colleagues can result in dysfunctional competition and conflict mechanisms that increase work-related stress (28, 41).

Our study aimed to explore associations between job characteristics, that could affect work-related stress, and some perceived organizational aspects in a sample of Italian bankers over the age of 50.

Literature shows that lower levels of supervisor support may increase the risk of high levels of work-related fatigue and burnout, as well as lower levels of social support from colleagues may raise the risk of developing stress complaints. Both phenomena seem to be more pronounced in older workers (48, 54, 55). In addition, it was observed that lack of skills, organizational support and discrimination are associated with work-related stress in older banking workers (1, 38, 51).

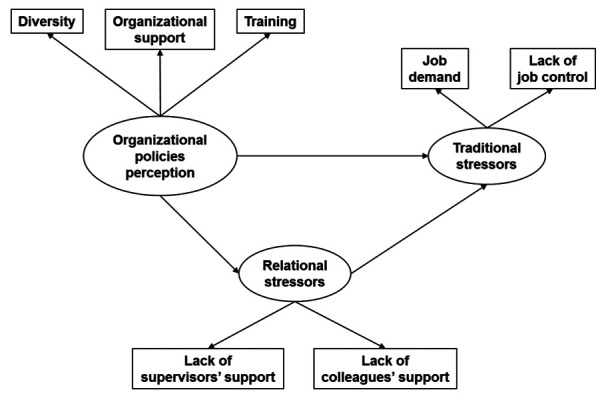

Consequently, a negative perception of organizational policies may have an inadequate impact on the awareness of supervisor and social support from colleagues, which can result in stress correlated factors. For the evaluation of these issues, we have proposed an original theoretical model, particularly focused on a construct of organizational policy perception. A workplace characterized by lack of organizational support and discriminations may strongly influence relational stress. Literature highlights the role of social support as a potential mediator (4, 35, 53) of the relationship between organizational policies and job demand and job control. The description of the theoretical model relating all the involved job related factors is presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

The proposed theoretical model

First of all, we wanted to test the association between perception of organizational policies and stress-related factors. Some stressful elements such as concern for the development of employee skills (training), the extent to which employees may be subject to stress or risks due to their diversity (diversity) and the extent to which the company appreciates and protects employees (organizational support) can contribute to work-related stress, and to its components: job demand and lack of job control.

Then we hypothesized that relational stressors (supervisor support and social support from colleagues) could be related to traditional stressors (job demand and lack of job control). In addition, we argued that organizational policies might result in a direct contribution to relational stressors and indirectly through such association can also influence traditional stressors.

We hypothesized a partial mediation as the relationship between lack of training and work-related stress for older banking workers has been highlighted in international literature (1, 22, 33, 34, 38, 51). For these reasons, we expected that perceptions of organizational policies both directly and indirectly affect work-related stress.

Methods

Participants

We have proposed to the H&S managers of a major Italian banking group to participate in a stress assessment. The managers of different bank branches on the Italian territory agreed to participate in the research and made available to their employees an adequate time to compile questionnaires during their working hours. As a compensation, we have released to each organization a report to be included in their risk assessment document (mandatory under the above mentioned Italian Legislative Decree no. 81/2008 and subsequent amendments).

The participating bank branches represented a convenient sample that also reflected a multitude of territorial environments, thus conferring greater validity to the results.

The questionnaires were administered online through the companies’ intranet portals. Anonymity and confidentiality in the responses were, however, fully assured. The questionnaires included a statement about personal data treatment, in accordance with the Italian privacy law (Italian Legislative Decree no. 196/2003 and subsequent amendments). The workers authorized and approved the use of anonymous/collective data for possible future scientific publications.

Participants were also informed that the survey was intended to fulfill legal obligations regarding the mandatory assessment of stress in the workplace, with the opportunity to use the findings to improve the quality of their working lives. In such a context, the compilation of the survey was very accurate and almost all the questionnaires were collected with complete data; a few missing elements were replaced with the means of the scales.

Instruments

Work-related stress was measured with the Stress Questionnaire (SQ), which assesses several psychosocial working variables related to work-related stress (19, 20, 33). The first version of the SQ was based on Karasek’s demand, control and support model and the Health and Safety Executive’s Management Standards work-related stress (13, 26). Based on an analysis of the literature concerning work-related stress, the SQ was further developed, adding emergent stress-related factors and emergent risks as well as recovery and economic stress (fear of crisis and non-employability) (19, 20, 33). Furthermore, the critical issues experienced in the job task were considered as well as in the physical and psychological context.

One of the most relevant features of the SQ is the psychosocial risk scale; it is based on five main psychosocial risks which might lead to stress correlated factors. The scale consists of 25 items and 5 subscales: job demand, job control, role, supervisors’ support, and colleagues’ support.

The SQ assesses five stress-related factors on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (absolutely agree) to 5 (absolutely disagree): a) role conflict, which appears when employees have no awareness of their roles and responsibilities (5 items; e.g. “I have a clear idea about what is expected of me at work”); b) colleagues’ support or collaboration and support among employees (5 items; e.g. “I get the support I need from colleagues”); c) supervisors’ support or the extent to which employees experience support and understanding from their supervisors/leaders (5 items; e.g. “My supervisor energizes me at work”); d) job demands, which refers to quantitative, demanding aspects of the job and to job pressure (6 items; e.g. “I have unrealistic deadlines”); and e) job control or job resources that pertain to the task (5 items; e.g. “I can plan my work”).

After recoding responses to positively worded items, the questionnaire gives a total score whereby a higher score indicates a greater risk of work-related stress.

Organizational policies were measured with a specific scale focusing on facilitating stress factors; this is included in the abovementioned SQ. Three scales of organizational policies were used for this study: 1) organizational support (4 items), the extent to which the organization values and cares for employees; 2) training (3 items), the concern for developing employees’ skills; and3) diversity (7 items), the extent to which employees may be subject to stress or risks for their diversity.

Demographic aspects were detected by questions in which information was requested regarding the gender, age, territorial area, job seniority and job position of responders.

Statistical analysis

The coefficients of correlation were calculated and structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine structural models. To examine the hypothesis, a series of analyses and comparisons of competitive models were conducted. Chi-square difference tests for nested models were conducted (44). In order to evaluate the fit of the models, multiple indices (of fit) were examined (5). One of the most used indices is the chi-square (χ2); a small χ2 indicated that the observed data was not significantly different from the hypothesized model. However, many authors have suggested that the chi-square test presents limitations, especially in large sample studies (49). Therefore, to support the appropriateness of the model, alternative indices, which seem preferable in large samples, were used:

- the goodness of fit index (GFI) (25);

- the comparative fit index (CFI) (3);

- the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) (47);

- the root mean square residual (RMR) (25);

- the incremental fit index (IFI) (5).

The following criteria were established to assess the model fit: GFI ≥0.90, AGFI ≥0.90, CFI ≥0.90, RMSEA <0.08, IFI ≥0.90 (45).

Results

In total, 2,007 Italian bank workers over fifty years of age took part in the study (the response rate was 37,8%): 71.2% were males and 28.8% females; 94.4% were aged between 51 and 60 years and 5.6% were over sixty years old; 73.1% had held job seniority for over 30 years; 26.3% had held job seniority for between 15 and 30 years (followed by 0.5% between 8 and 15 and 0.1% between 3 and 7). With respect to the territorial area, the sample was conveniently divided on the Italian territory: 42.9% from Northern Italy, 41.3% from Central Italy and Sardinia, 15.8% from Southern Italy and Sicily. This descriptive subdivision reflects the organization of the branches in areas of geographical operations by the banking group.

Table 1 shows correlations among the research variables. All dimensions presented in the model were correlated.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, alpha and correlations among variables

| Mean | DS | Alpha | V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | V5 | V6 | V7 | V8 | |

| V1: Lack of supervisors’ support | 2.66 | 0.84 | 0.80 | 1 | 0.283** | 0.359** | 0.531** | 0.354** | 0.296** | 0.396** | 0.472** |

| V2: Job Demands | 3.06 | 0.75 | 0.81 | 0.283** | 1 | 0.461** | 0.340** | 0.081** | 0.315** | 0.306** | 0.409** |

| V3: Lack of Job Control | 2.72 | 0.72 | 0.79 | 0.359** | 0.461** | 1 | 0.402** | 0.428** | 0.254** | 0.374** | 0.455** |

| V4: Lack of colleagues’ support | 2.46 | 0.68 | 0.77 | 0.531** | 0.340** | 0.402** | 1 | 0.344** | 0.319** | 0.345** | 0.403** |

| V5: Role conflict | 2.11 | 0.68 | 0.83 | 0.354** | 0.081** | 0.428** | 0.344** | 1 | 0.223** | 0.325** | 0.320** |

| V6: Diversity | 2.21 | 0.67 | 0.77 | 0.296** | 0.315** | 0.254** | 0.319** | 0.223** | 1 | 0.286** | 0.291** |

| V7: Training | 3.30 | 0.81 | 0.70 | 0.396** | 0.306** | 0.374** | 0.345** | 0.325** | 0.286** | 1 | 0.658** |

| V8: Organizational Support | 3.41 | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.472** | 0.409** | 0.455** | 0.403** | 0.320** | 0.291** | 0.658** | 1 |

Note: Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

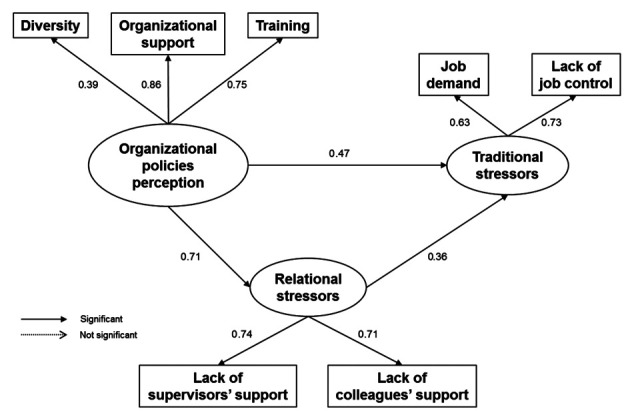

The results from the structural equation modeling supported the theoretical model (figure 1). The value of Chi Square was 173 (df=11), whereas for the competitive model (with total mediation) Chi Square was 284 (df=12). As shown in figure 2, organizational policies are associated with stress correlated factors – as well as with two of its components: job demand and lack of job control (β=0.468) – and are associated with perceptions of supervisor support and social support from colleagues (β=0.710). Finally, perceptions of supervisor support and social support from colleagues are associated with stress outcomes regarding job demand and lack of job control (β=0.365).

Figure 2.

The proposed structural equation model

Hypotheses one and two are confirmed: perceptions of supervisor support and social support from colleagues (relational stressors) partially mediate the organizational policies/work-related stress relationship, and organizational policies (training, diversity and organizational support) influence work-related stress (job demand and lack of job control), both directly and indirectly, through the mediation of relational stress (supervisor support and colleagues support). The partial mediation model has better fit indices.

An evaluation of the considered indices shows that this model meets the recommended criteria more fully than competitive models: GFI=0.97, AGFI=0.94, CFI=0.96, RMSEA=0.08, IFI=0.96. In combination, these indices suggest a satisfactory fit to the data. An examination of the path coefficients for the model (figure 2) indicates the proposed paths are significant, with standardized estimates ranging from 0.36 to 0.86. The tested model offered better results than a competitive model, on which a total mediation was tested, rather than partial (p<0.001).

Discussion

The present study supports the importance of negative organizational policies as predictors of undesirable outcome and occupational stress in aged workers. The aim of the study was to explore the associations between some organizational perceived aspects and job characteristics that could affect work-related stress in a convenient sample of Italian workers over the age of 50 years in the banking sector.

The results confirmed the hypotheses expressed. We found that supervisor support and social support from colleagues partially mediate the organizational policies/work-related stress relationship. Statistical analyses showed that negative organizational policies made job perceptions more competitive and decreased positive opinions of the leadership for over-fifty employees.

The role of social support has been extensively investigated in the literature. Viswesvaran et al. (53), in a meta-analysis, reported two studies on the various models for the role of social support in the process of work-related stress. Results of the second study indicated that social support had a threefold effect: social support reduced the strains experienced, mitigated perceived stressors, and moderated the stressor/strain relationship.

Blanch (4), a group of administrative and technical workers, evaluated whether social support mediated the effect of job demand or job control on job strain. Results showed that social support was a consistent mediator in the association of job control with job strain. The effect of job control on job strain was fully mediated by social support from supervisors and coworkers.

Nahum-Shani and Bamberger (35), in a random sample of blue-collar workers, demonstrated that the buffering effect of social support on the relationship between work hours, on the one hand, and employee health and well-being, on the other, varies as a function of the pattern of exchange relations between an employee and his/her close support providers.

Moreover, we found that positive organizational policies (training, diversity and organizational support) influenced work-related stress (job demand and lack of job control), both directly and indirectly, through the mediation of relational stress (supervisors support and support from colleagues).

In parallel, these negative organizational perceptions may play a role on the extent to which workers feel themselves to be supported by their supervisors and colleagues, and all these factors have indirect effects on work-related stress levels. Consequently, aged workers who perceive negative organizational policies and lacking social support are more likely to report stress. The association of a lack of social support with work-related stress for these workers agrees with the current literature (4, 35, 53, 55).

Zoer et al. (55) found that in workers aged between 56 and 66 years old lower levels of supervisor support increased the risk of high levels of work-related fatigue and burnout, and lower levels of social support from colleagues increased the risk of developing stress complaints.

Other studies were a bit controversial regarding age differences and social stressors. For example, Pereira et al found no significant links between age and social stressors (37). Similarly, in a study by Kumar and Sundaram, the variables that include age group, were not found to be significantly associated with the stress level (38).

According to several researches, companies have a great responsibility in the diffusion of negative or positive policies towards older employees (13, 17, 29). Indeed, our findings suggest that organizational policies may affect work-related stress both directly and indirectly via the mediation of social support perceptions from superiors and colleagues. These results confirm the relevant role of social support in the organizational policies/stress relationship.

As a whole, our study contributes to increase knowledge about work-related stress in the banking sector, with particular reference to workers over 50 years old. Results suggest that specific organizational programs for the senior workers may be important in preventing work-related stress. For example, workers often complain about a lack of support from their supervisors. Supervisor training could be important for reducing the main stress factor of these workers. Providing supervisors with necessary skills and information on the difficulties this target of workers currently is living might have a favorable effect on both individuals and teams. Therefore, our findings confirm that today it is still necessary to invest in improving attitudes towards older workers. They need to be valued for their precious skills and experience and encouraged to continue working and actively participating in the society.

Despite the strengths of this study, some limitations must be addressed. First, we have to consider with attention cross-sectional data because causality cannot be inferred. In addition, our study is based on self-reported questionnaires, as the only one source of information for data collection, which could present common bias and could inflate correlations between variables (39). Moreover, the sample is limited and not representative of the Italian population. Additionally, the survey was administered on-line, and this did not allow workers to be supported interactively during the compilation of the survey. In view of the above, we believe that further studies are needed to overcome the limitations we have described in the banking and in other employment sectors.

Nowadays, an integrated evaluation of the effects of organizational aspects of work and of work-related stressors is needed to implement the protection of health of older workers, both physical and mental, in banks and, more generally, in every kind of workplace. Consequently, we strongly recommend to companies the adoption of strategies aimed at reducing bankers’ resignations because of a lack of training and a lack of social support, also to prevent the onset of work-related stress, as well as improving wellbeing at work. Similarly, we believe it is necessary to consider that sometimes younger workers have little awareness of their roles and responsibilities.

Further research will help to understand more thoroughly if the emerged issues are effectively related to age. This can be assessed through a case-control study that also includes younger workers

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported by the authors

References

- 1.Amigo I, Asensio E, Menéndez I, et al. Working in direct contact with the public as a predictor of burnout in the banking sector. Psicothema. 2014;26:222–226. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2013.282. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2013.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baltes MM, Carstensen LL. Social psychological theories and their application to aging: From individual to collective social psychology. In: Bengtson VL, Schaie KW, editors. Handbook of theories of aging. New York (N.Y.): Springer; 1999. pp. 209–226. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107:238–426. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanch A. Social support as a mediator between job control and psychological strain. Soc Sci Med. 2016;157:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.04.007. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bollen KA. New York (N.Y.): Wiley; 1989. Structural equations with latent variables. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowen CE, Staudinger UM. Relationship between age and promotion orientation depends on perceived older worker stereotypes. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2013;68(1):59–63. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs060. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carpentieri JD, Elliott J, Brett CE, et al. Adapting to aging: older people talk about their use of selection, optimization, and compensation to maximize well-being in the context of physical decline. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2017;72(2):351–361. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw132. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carstensen LL, Turan B, Scheibe S, et al. Emotional experience improves with age: evidence based on over 10 years of experience sampling. Psychol Aging. 2011;26(1):21–33. doi: 10.1037/a0021285. doi: 10.1037/a0021285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan MY, Na J, Agres PF, et al. Socioeconomic status moderates age-related differences in the brain’s functional network organization and anatomy across the adult lifespan. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(22):E5144–E5153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1714021115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1714021115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cloostermans L, Bekkers MB, Uiters E, Proper KI. The effectiveness of interventions for ageing workers on (early) retirement, work ability and productivity: a systematic review. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2015;88:521–532. doi: 10.1007/s00420-014-0969-y. doi: 10.1007/s00420-014-0969-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Converso D, Viotti S. Post-traumatic stress reaction in a sample of bank employees victims of robbery in the workplace: the role of pre-trauma and peri-trauma factors. Med Lav. 2014;105:243–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costa G. Work and ageing. Med Lav. 2010;101(Suppl 2):57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards J, Webster S, Van Laar D, Easton S. Psychometric analysis of the UK Health and Safety Executive‘s Management Standards work-related stress Indicator Tool. Work Stress. 2008;22:96–107. [Google Scholar]

- 14.European Observatory of Working Life. 2015 Living longer, working better – active ageing in Europe. Available online at: http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/observatories/eurwork. (last accessed 19-02-2018). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eurostat Statistics Explained. 2016 Employment statistics - Data from November 2016. Available online at; http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Employment_statistics. (last accessed 19-02-2018) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fichera GP, Fattori A, Neri L, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder among bank employee victims of robbery. Occup Med (Lond). 2015;65:283–289. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqu180. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqu180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher GG, Chaffee DS, Tetrick LE, et al. Cognitive functioning, aging, and work: A review and recommendations for research and practice. J Occup Health Psychol. 2017;22(3):314–336. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000086. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giga SI, Hoel H. Violence and stress at work in financial services – Working Paper. Geneva (Switzerland): International Labour Office. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giorgi G, Arcangeli G, Cupelli V. Naples (Italy): Edises; 2012. Work-related stress – leaders and collaborators compared. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giorgi G, Arcangeli G, Cupelli V. Florence (Italy): Hogrefe; 2013. SQ - Stress Questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giorgi G, Arcangeli G, Perminiene M, et al. Work-Related Stress in the Banking Sector: A Review of Incidence, Correlated Factors, and Major Consequences. Front Psychol. 2017;12(8):2166. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02166. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giorgi G, Fiz Perez FS, Castiello D’Antonio A, et al. Psychometric properties of the Impact of Event Scale-6 in a sample of victims of bank robbery. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2015;8:99–104. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S73901. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S73901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gordon J, Jordan L. Older is wiser? It depends who you ask… and how you ask. Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2017;24:94–114. doi: 10.1080/13825585.2016.1171292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ilmarinen J. Promoting active ageing in the workplace. Bilbao (Spain): EU-OSHA. 2012 Available online at: https://osha.europa.eu/en/tools-and-publications/publications/articles/promoting-active-ageing-in-the-workplace. (last accessed 19-02-2018) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jöreskog K, Sörbom D. Chicago (IL): Scientific Software International Inc.; 1993. LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karasek RA. Job Demands, Job Decision Latitude, and Mental Strain: Implications for Job Redesign. Adm Sci Q. 1979;24:285–308. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kenny GP, Groeller H, McGinn R, Flouris AD. Age, human performance, and physical employment standards. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41((6 Suppl 2)):S92–S107. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2015-0483. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2015-0483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kristman VL, Shaw WS, Reguly P, et al. Supervisor and Organizational Factors Associated with Supervisor Support of Job Accommodations for Low Back Injured Workers. J Occup Rehabil. 2017;27(1):115–127. doi: 10.1007/s10926-016-9638-1. doi: 10.1007/s10926-016-9638-1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28a.Kumar SG, Sundaram ND. Prevalence of stress level among Bank employees in urban Puducherry, India. Ind Psychiatry J. 2014 Jan;23(1):15–7. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.144938. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.144938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lansisalmi H, Peiro J, Kivimaki M. Collective stress and coping in the context of organizational culture. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2000;9:527–559. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lockenhoff CE, Carstensen LL. Socioemotional Selectivity Theory, Aging, and Health: The Increasingly Delicate Balance Between Regulating Emotions and Making Tough Choices. J Pers. 2004;72(6):1395–1424. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00301.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lucifora C, Cappellari L, Cottini E. Work, Retirement and Health: An Analysis of the Socio-economic Implications of Active Ageing and their Effects on Health. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2014;203:172–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lunau T, Wahrendorf M, Dragano N, Siegrist J. Work stress and depressive symptoms in older employees: impact of national labour and social policies. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1086. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1086. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1086 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mucci N, Giorgi G, Cupelli V, et al. Work-related stress assessment in a population of Italian workers. The Stress Questionnaire. Sci Total Environ. 2015;502:673–9. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.09.069. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mucci N, Giorgi G, Fiz Perez J, et al. Predictors of trauma in bank employee robbery victims. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:2605–12. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S88836. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S88836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nahum-Shani I, Bamberger PA. Explaining the Variable Effects of Social Support on Work-Based Stressor-Strain Relations: The Role of Perceived Pattern of Support Exchange. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2011;114(1):49–63. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2010.09.002. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nilsson K. Conceptualisation of ageing in relation to factors of importance for extending working life - a review. Scand J Public Health. 2016;44(5):490–505. doi: 10.1177/1403494816636265. doi: 10.1177/1403494816636265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pereira D, Gross S. Elfering A: Social Stressors at Work, Sleep, and Recovery. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2015;41:93–101. doi: 10.1007/s10484-015-9317-6. doi: 10.1007/s10484-015-9317-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petarli GB, Zandonade E, Bresciani Salaroli L, Souza Bissoli N. Assessment of occupational stress and associated factors among bank employees in Vitoria, State of Espírito Santo, Brazil. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2015;20:3925–3934. doi: 10.1590/1413-812320152012.01522015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff N. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88:879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pohl M, Tortella T. Abingdon-on-Thames (U.K.): Routledge; 2017. A century of banking consolidation in Europe: the history and archives of mergers and acquisitions. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Puah LN, Ong LD, Chong WY. The effects of perceived organizational support, perceived supervisor support and perceived co-worker support on safety and health compliance. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2016;22:333–339. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2016.1159390. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2016.1159390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rauschenbach C, Göritz A, Hertel G. Age Stereotypes about Emotional Resilience at Work. Educ Gerontol. 2012;38:511–519. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rauschenbach C, Krumm S, Thielgen M, Hertel G. Age and work-related stress: a review and meta-analysis. J Manag Psychol. 2013;28:781–804. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Satorra A, Bentler P. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika. 2001;66:507–514. doi: 10.1007/s11336-009-9135-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schumacher RE, Lomax RG. Mahwah (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Association; 1996. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Staudinger UM, Finkelstein R, Calvo E, Sivaramakrishnan K. A Global View on the Effects of Work on Health in Later Life. Gerontologist. 2016;56(Suppl 2):S281–92. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw032. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steiger JH. Structural Model Evaluation and Modification: An Interval Estimation Approach. Multivariate Behav Res. 1990 Apr 1;25(2):173–80. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steinhardt MA, Dolbier CL, Gottlieb NH, et al. The relationship between hardiness, supervisor support, group cohesion, and job stress as predictors of job satisfaction. Am J Health Promot. 2003;17:382–389. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-17.6.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. New York (N.Y.): HarperCollins College Publishers; 1996. Using multivariate statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tabanelli MC, Bonfiglioli R, Violante FS. Bank robberies: A psychological protocol of intervention in financial institutions and principal effects. Work. 2013 doi: 10.3233/WOR-131625. doi: 10.3233/WOR-131625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Valente MS, Menezes PR, Pastor-Valero M, Lopes CS. Depressive symptoms and psychosocial aspects of work in bank employees. Occup Med (Lond) 2016;66:54–61. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqv124. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqv124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Viotti S, Guidetti G, Loera B, et al. Stress, work ability, and an aging workforce: A study among women aged 50 and over. Int J Stress Manag. 2017;24(Suppl 1):98–121. doi: 10.1037/str0000031. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Viswesvaran C, Sanchez JI, Fisher J. The role of social support in the process of work stress: A meta-analysis. J Vocat Behav. 1999;54:314–334. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1998.1661. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang T, Shen YM, Zhu M, et al. Effects of Co-Worker and Supervisor Support on Job Stress and Presenteeism in an Aging Workforce: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;13(1):ijerph13010072. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13010072. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13010072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zoer I, Ruitenburg MM, Botje D, et al. The associations between psychosocial workload and mental health complaints in different age groups. Ergonomics. 2011 Oct;54:943–952. doi: 10.1080/00140139.2011.606920. doi: 10.1080/00140139.2011.606920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]