Abstract

Background:

Vitiligo is an acquired, idiopathic, and common depigmentation disorder. The values of various epidemiologic parameters are often doubtful due to the methodological weaknesses of the studies.

Aims:

To elicit the magnitude of various epidemiological parameters and important correlates of vitiligo.

Materials and Methods:

Every vitiligo patient attending the outpatient department of medical colleges spread over most of the Indian states were examined over a period of 1 year. Various epidemiological and clinical variables were examined and compared with age and sex-matched controls (registered in the Clinical Trial Registry of India CTRI/2017/06/008854).

Results:

A total of 4,43,275 patients were assessed in 30 medical colleges from 21 Indian states. Institutional prevalence of vitiligo was 0.89% (0.86% in males and 0.93% in females, P < 0.001). The mean age at presentation and mean age at onset were 30.12 ± 17.97 years and 25.14 ± 7.48 years, respectively. Head–neck was the most common primary site (n = 1648, 41.6%) and most commonly affected site (n = 2186, 55.17%). Most cases had nonsegmental vitiligo (n = 2690, 67.89%). The disease started before 20 years of age in more than 46% of cases. About 77% of all cases had signs of instability during the last 1 year. The family history, consanguinity, hypothyroid disorders, and depressed mood were significantly (P < 0.001) higher among the cases. First, second, and third-degree family members were affected in 269 (60.04%), 111 (24.78%), and 68 (15.18%) cases, respectively. Work-related exposure to chemicals was significantly higher among cases (P < 0.008). Obesity was less common among vitiligo cases [P < 0.001, odds ratio (OR) 0.78, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.71–0.86].

Conclusion:

This is one of the largest studies done on vitiligo in India. The prevalence of vitiligo was found to be 0.89% among hospital attendees. Prevalence of vitiligo was higher among females than in males and prevalence of family history, consanguinity, hypothyroid disorders were higher in vitiligo than among controls.

KEY WORDS: Epidemiology, family history, India, multicentric study, prevalence, psychosocial, vitiligo

Introduction

Vitiligo is a common, acquired, progressive depigmenting disorder that results from the destruction of melanocytes in the interfollicular and/or intrafollicular region.[1] Inheritance of vitiligo is polygenic and etiology is multifactorial.[2] Role of ethnicity, environmental, occupational, metabolic, autoimmune, and other diseases is implicated in the etiopathogenesis of the disease.[3] The psychosocial impact of the disease is known to be higher in the darker races.[4,5]

Though studies have evaluated the clinical and epidemiological aspects, the usefulness of many of these studies is limited by their shorter duration, limited geographical area, small sample size, absence of a control group, and many other methodological weaknesses. Thus, data on various epidemiological parameters of vitiligo and its associations need to be validated with larger surveys done for a longer period of time.

In this multicentric case–control study, spanning over 1 year, we have evaluated a large number of samples over wide geographical regions across India and examined various clinical, psychosocial and demographic parameters associated with vitiligo.

Materials and Methods

Subjects were selected from the dermatology outpatient departments (OPD) of different medical colleges spread over most parts of India. A maximum of two medical colleges per state was included. Only, in the state of Nagaland, where there was no medical college at the time of the study, one large tertiary care, referral hospital was included.

All investigators were qualified dermatologists. They were trained for the study. Two short surveys were conducted to evaluate the training. A trial run of 2 months was conducted maintaining complete study protocol. Then, the study proper was started simultaneously in all the centers and continued for 1 year (52 weeks).

Informed and signed consent form (consent from parents/guardians for children aged below 18 years) was obtained from each participant.

Days of the week on which cases were selected were decided randomly for every center before the study started and remained constant for the entire period. On those days, all vitiligo cases attending the OPD were included except those who were unwilling, refused examinations, and moribund patients. The very next sex and age-matched (closest possible) non-vitiligo patient from the same OPD on the same day was included as control. Total number and some basic details like sex distribution of all patients attending on those days were recorded.

Patients were examined and demographic and clinical details were recorded in a predesigned printed proforma. All recorded data were then submitted in a dedicated, highly secured web-based system. Submitted data were collected in a centralized repository inaccessible to the investigators.

Vitiligo cases were clinically classified as per the latest global consensus.[6] Stability was assessed according to vitiligo disease activity (VIDA) scoring.

We used a simple, nonvalidated set of questionnaire to identify 'depressed mood'. We avoided the evaluation of 'depression' that would have necessitated a detailed and lengthy questionnaire to keep it simple as well as feasible in busy OPD in this multicenter study.

The questionnaire inquired about (i) whether the individual had a feeling of a depressed mood about their vitiligo, (ii) whether the depressed mood limited his/her daily activities like going to school, playground, office, and meeting people, and (iii) whether the disease was instigating suicidal ideas in him/her.

Laboratory reports, if available, like thyroid profile, antithyroid antibodies, blood sugar, renal function, liver function, gastrointestinal and hematological systems were included.

All centers obtained permission from the respective institutional ethics committee. The study was registered in the Clinical Trial Registry of India (CTRI), [No. CTRI/2017/06/008854].

Statistical analysis

Data collected were analyzed using statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) ver. 20.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). Chi-square test was applied to compare nonparametric variables like sex, religion, level of education, presence of family history of vitiligo, consanguinity, obesity, thyroid abnormality, anti-thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibody, diabetes, and depression-related issues between cases and controls and male and female vitiligo patients and clinical types of vitiligo. Fisher's exact test was applied to compare the presence of antithyroglobulin (TG) antibody between cases and controls. Z test was used to compare the rates of exposure to chemicals and manual labor between cases and controls. Unpaired t -test was applied to compare the difference of mean age at presentation and at onset between cases and controls and between male and female vitiligo patients.

Results

A total of 30 centers from 21 Indian states participated in the study. A total of 4,43,275 patients (2,24077 male, 50.55%, 2,19198 female, 49.45%) attended the OPD during the study period, across all the centers and were evaluated. A total of 7,924 subjects were included with 3,962 vitiligo cases and an equal number of sex and age-matched controls.

The mean age of patients was 30.12 ± 17.97 years (3 months to 88 years) and 30.41 ± 17.46 years (3 months to 86 years) among cases and controls, respectively.

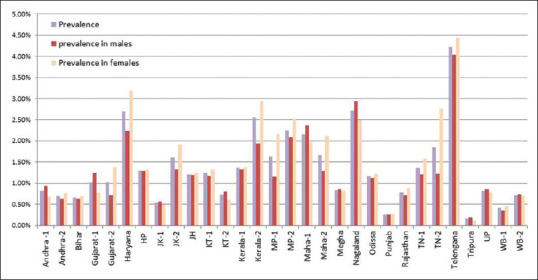

The overall institutional prevalence of vitiligo was found to be 0.89%. Institutional prevalence of vitiligo in females was higher in most Indian states and overall was significantly higher (0.93%) than in males (0.86%) (P < 0.001), [Table 1, Figure 1]. Among vitiligo cases, females outnumbered males (2,043; 51.6% vs 1,919; 48.4%) [Table 2].

Table 1.

Center wise data of cases and controls

| State# | OPD male | OPD fem | Total | Male vitiligo | Female vitiligo | Total vitiligo | Control | % of vit in OPD | % of male vit in OPD | % of fem vit in OPD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andhra Pradesh-1 | 4276 | 3980 | 8256 | 40 | 27 | 67 | 67 | 0.81% | 0.94% | 0.68% |

| Andhra Pradesh-2 | 32402 | 36755 | 69157 | 204 | 278 | 482 | 482 | 0.70% | 0.63% | 0.76% |

| Bihar | 5708 | 4735 | 10443 | 36 | 33 | 69 | 69 | 0.66% | 0.63% | 0.70% |

| Gujarat-1 | 4205 | 3862 | 8067 | 52 | 30 | 82 | 82 | 1.02% | 1.24% | 0.78% |

| Gujarat-2 | 2548 | 2168 | 4716 | 18 | 30 | 48 | 48 | 1.02% | 0.71% | 1.38% |

| Haryana | 1436 | 1343 | 2779 | 32 | 43 | 75 | 75 | 2.70% | 2.23% | 3.20% |

| Himachal Pradesh | 12376 | 13718 | 26094 | 158 | 181 | 339 | 339 | 1.30% | 1.28% | 1.32% |

| Jammu & Kashmir-1 | 15230 | 13577 | 28807 | 86 | 67 | 153 | 153 | 0.53% | 0.56% | 0.49% |

| Jammu & Kashmir-2 | 4070 | 3868 | 7938 | 54 | 74 | 128 | 128 | 1.61% | 1.33% | 1.91% |

| Jharkhand | 3024 | 2245 | 5269 | 36 | 28 | 64 | 64 | 1.21% | 1.19% | 1.25% |

| Karnataka-1 | 6148 | 5997 | 12145 | 72 | 79 | 151 | 151 | 1.24% | 1.17% | 1.32% |

| Karnataka-2 | 5095 | 4244 | 9339 | 41 | 26 | 67 | 67 | 0.72% | 0.80% | 0.61% |

| Kerala-1 | 2405 | 2611 | 5016 | 32 | 36 | 68 | 68 | 1.36% | 1.33% | 1.38% |

| Kerala-2 | 566 | 847 | 1413 | 11 | 25 | 36 | 36 | 2.55% | 1.94% | 2.95% |

| Madhya Pradesh-1 | 4254 | 3846 | 8100 | 49 | 83 | 132 | 132 | 1.63% | 1.15% | 2.16% |

| Madhya Pradesh-2 | 2743 | 1748 | 4491 | 57 | 44 | 101 | 101 | 2.25% | 2.08% | 2.52% |

| Maharastra-1 | 2839 | 3303 | 6142 | 67 | 65 | 132 | 132 | 2.15% | 2.36% | 1.97% |

| Maharastra-2 | 8052 | 6498 | 14550 | 104 | 137 | 241 | 241 | 1.66% | 1.29% | 2.11% |

| Meghalaya | 7190 | 6474 | 13664 | 61 | 53 | 114 | 114 | 0.83% | 0.85% | 0.82% |

| Nagaland | 4755 | 5123 | 9878 | 140 | 128 | 268 | 268 | 2.71% | 2.94% | 2.50% |

| Odissa | 8762 | 7321 | 16083 | 99 | 89 | 188 | 188 | 1.17% | 1.13% | 1.22% |

| Punjab | 35248 | 34146 | 69394 | 87 | 93 | 180 | 180 | 0.26% | 0.25% | 0.27% |

| Rajasthan | 13328 | 9305 | 22633 | 95 | 82 | 177 | 177 | 0.78% | 0.71% | 0.88% |

| Tamil Nadu-1 | 2405 | 1898 | 4303 | 29 | 30 | 59 | 59 | 1.37% | 1.21% | 1.58% |

| Tamil Nadu-2 | 1392 | 941 | 2333 | 17 | 26 | 43 | 43 | 1.84% | 1.22% | 2.76% |

| Telengana | 1880 | 1486 | 3366 | 76 | 66 | 142 | 142 | 4.22% | 4.04% | 4.44% |

| Tripura | 6310 | 6524 | 12834 | 12 | 8 | 20 | 20 | 0.16% | 0.19% | 0.12% |

| Uttar Pradesh | 6047 | 6566 | 12613 | 52 | 51 | 103 | 103 | 0.82% | 0.86% | 0.78% |

| West Bengal-1 | 10389 | 14518 | 24907 | 36 | 65 | 101 | 101 | 0.41% | 0.35% | 0.45% |

| West Bengal-2 | 8994 | 9551 | 18545 | 66 | 66 | 132 | 132 | 0.71% | 0.73% | 0.69% |

| Total | 224077 | 219198 | 443275 | 1919 | 2043 | 3962 | 3962 | 0.89% | 0.86% | 0.93% |

OPD: Outpatient department; Vit: vitiligo; Fem: female

Figure 1.

Institutional prevalence of vitiligo (overall, in males and in females) in all the centres (Andhra = Andhra Pradesh, HP = Himachal Pradesh, JH = Jharkhand, JK = Jammu and Kashmir, KT = Karnataka, Maha = Maharastra, Megha = Meghalaya, MP = Madhya Pradesh, TN = Tamil Nadu, UP = Uttar Pradesh, WB = West Bengal. The number (1, 2) beside the state indicates the centers in that state)

Table 2.

Differences in the clinico-demographic variables among cases and controls

| Clinical and demographic variables | Status | Case (n=3962) | Control (n=3962) | P | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 1919 (48.44%) | 1930 (48.71%) | 0.8 | 0.99 (0.90-1.08) |

| Female | 2043 (51.56%) | 2032 (51.29%) | |||

| Age (yrs)- mean, (SD) | 30.12 (17.97364) | 30.41 (17.45753) | 0.47 | ||

| Religion | Hindu -n (%) | 2758 (69.61%) | 2691 (67.92%) | 0.17 | |

| Muslim -n (%) | 764 (19.28%) | 824 (20.8%) | |||

| Christian-n (%) | 319 (8.05%) | 300 (7.57%) | |||

| Sikh-n (%) | 102 (2.57%) | 116 (2.93%) | |||

| Other-n (%) | 19 (0.48%) | 31 (0.78%) | |||

| Occupation | Exposure to chemicals like cement, rubber, plastic, fertilizers etc., n (%) | 450 (11.36%) | 377 (9.52%) | 0.008 (Z test) | |

| Manual labor with higher chances of friction, weight bearing, pressure etc., n (%) | 165 (4.16%) | 163 (4.11%) | 0.96 (Z test) | ||

| Education | Undergraduate-n (%) | 3172 (80.06%) | 3065 (77.36%) | 0.003 | 1.18 (1.05-1.31) |

| ≥Graduate -n (%) | 790 (19.94% | 897 (22.64%) | |||

| Consanguinity | Present -n (%) | 283 (7.14%) | 163 (4.11%) | <0.001 | 1.79 (1.46-2.20) |

| Absent -n (%) | 3679 (92.86%) | 3799 (95.89%) | |||

| Family history | Present -n (%) | 448 (11.31%) | 235 (5.92%) | <0.001 | 2.03 (1.73-2.40) |

| Absent -n (%) | 3514 (88.69%) | 3727 (94.08%) | |||

| Obesity | Overweight and obese (BMI ≥23) | 1548 (3.07%) | 1786 (45.08%) | <0.001 | 0.78 (0.71-0.86) |

| Non-obese (BMI <23) | 2414 (60.93%) | 2176 (54.92%) | |||

| Thyroid abnormality- overall | Present -n (%) | 145 (11.38%) | 55 (5.90%) | <0.001 | 2.05 (1.47-2.87) |

| Total number of persons tested 1274 (case), 932 (control) | Absent -n (%) | 1129 (88.62%) | 877 (94.10%) | ||

| Hypothyroid disorders | Present -n (%) | 134 (10.52%) | 50 (5.35%) | <0.001 | 2.07 (1.46-2.94) |

| Total number of persons tested 1274 (case), 932 (control) | Absent -n (%) | 1140 (89.48%) | 882 (94.64%) | ||

| Hyperthyroid disorders | Present -n (%) | 11 (0.86%) | 5 (0.51%) | 0.37 | 1.61 (0.52-5.34) |

| Total number of persons tested 1274 (case), 932 (control) | Absent -n (%) | 1263 (99.14%) | 927 (99.46%) | ||

| Positive Anti-TG antibody | Present -n (%) | 10 (11.36%) | 1 (1.69%) | 0.025 (Fisher exact test) | 7.44 (0.93-159.57) |

| Total persons tested 88 (case), 59 (control) | Absent -n (%) | 78 (88.64%) | 58 (98.31%) | ||

| Positive Anti-TPO antibody | Present -n (%) | 13 (13.27%) | 2 (3.39%) | 0.079 (Yates corrected) | 4.36 (0.88-29.012) |

| Total persons tested- 98 (cases), 59 (control) | Absent -n (%) | 85 (86.73%) | 57 (96.71%) | ||

| Diabetes | Type 1 diabetes-n (%) | 17 (0.78%) | 13 (0.83%) | P=0.83 | |

| Total persons tested -2186 (case), 1569 (control) | Type 2 diabetes-n (%) | 116 (5.65%) | 90 (5.74%) | ||

| No diabetes-n (%) | 2053 (93.92%) | 1466 (93.44%) | |||

| Depression among individual aged ≥10 years | Present | 857 (24.51%) | 338 (9.48%) | <0.001 | 3.10 (2.70-3.56) |

| Absent | 2640 (75.49%) | 3229 (90.52%) | |||

| Depression with psychosocial impact | Present | 157 (18.82%) | 33 (9.97%) | P<0.001 | 2.09 (1.38-3.19) |

| Absent | 677 (81.18%) | 298 (90.03%) |

TPO: Thyroid peroxidase; TG: Thyroglobulin; OR: Odds ratio, CI: Confidence interval; SD: Standard deviation

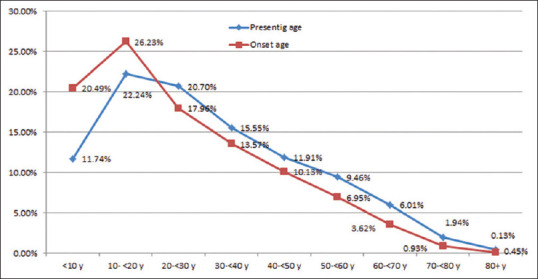

Mean 'age at onset' of vitiligo was 25.14 ± 7.48 years (1 month to 82.5 months). It was significantly higher (P < 0.001) among males (26.345 ± 18.1 years) than in females (24.021 ± 17.21 years) [Table 3]. Age at onset was earlier in segmental vitiligo (SV) than in non-segmental vitiligo (NSV) (17.3 ± 13.42 years in SV vs 26.59 ± 17.95 years in NSV).

Table 3.

Major differences between male and female vitiligo groups

| Clinical and demographic characteristics | Status | Male (n=1919) | Female (n=2043) | P | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at presentation (in year) mean, (SD) | 31.21 (18.71) | 29.09 (17.19) | <0.001 | ||

| Onset age- (in year) mean, (SD) | 26.345 (18.1) | 24.021 (17.21) | <0.001 | ||

| Duration of disease- (in year) mean, (SD) | 4.98 (8.124) | 5.11 (7.853) | 0.61 | ||

| Hypothyroid | Present-n (%) | 29 (5.06%) | 105 (14.98%) | <0.001 | 3.30 (2.12-5.19) |

| Total persons tested - 573 (cases), 701 (control) | Absent-n (%) | 544 (94.94%) | 596 (85.02%) | ||

| Hyperthyroid | Present-n (%) | 5 (0.87%) | 6 (0.86%) | 0.97 | 0.98 (0.26-3.71) |

| Total persons tested - 573 (cases), 701 (control) | Absent-n (%) | 568 (99.13%) | 695 (99.14) | ||

| Positive anti-TG antibody | Present-n (%) | 5 (13.16%) | 5 (10%) | 0.64 | 1.36 (0.31-6.04) |

| Total persons tested - 38 (cases), 50 (control) | Absent-n (%) | 33 (86.84%) | 45 (90%) | ||

| Positive anti-TPO antibody | Present-n (%) | 5 (12.2%) | 8 (14.04%) | 0.79 | 0.85 (0.22-3.20) |

| Total persons tested - 41 (cases), 57 (control) | Absent-n (%) | 36 (87.80%) | 49 (85.96%) | ||

| Type 2 diabetes | Present-n (%) | 55 (5.29%) | 61 (5.32%) | 0.97 | 0.99 (0.67-1.47) |

| Total persons tested - 1040 (cases), 1146 (control) | Absent-n (%) | 978 (94.04%) | 1075 (93.80%) | ||

| Type 1 diabetes | Present-n (%) | 7 (0.55%) | 10 (0.87%) | 0.35 | 0.63 (0.22-1.80) |

| Total persons tested - 1040 (cases), 1146 (control) | Absent-n (%) | 978 (94.04%) | 1075 (93.80%) | ||

| Family history of vitiligo | Present- n (%) | 208 (10.84%) | 240 (11.75%) | 0.36 | 1.09 (0.89-1.34) |

| Absent- n (%) | 1711 (89.16%) | 1803 (88.25%) | |||

| Depression among individual aged ≥10 years | Present | 357 (20.76%) | 500 (28.14%) | <0.001 | 1.49 (1.28-1.75) |

| Absent | 1363 (79.24%) | 1277 (71.86%) |

TPO: Thyroid peroxidase; TG: Thyroglobulin; SD: Standard deviation

Age at onset as well as age at presentation, both peaked at the second decade. More than 46% of all cases had onset before 20 years of age and about 80% of cases developed vitiligo before 40 years of age [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Trends in the presenting age and onset age in different age categories

The mean duration of the disease (vitiligo) was 5.05 ± 16.028 years, (range - <1 month to 76.5 years). No association was found between the institutional prevalence of vitiligo and religion [Table 2].

Positive family history and consanguinity were significantly higher among cases than in controls (P < 0.001, OR 2.03, 95% CI-1.73-2.40) [Table 2]. A positive history of vitiligo was found in 269 (6.79%), 111 (2.80%), and 68 (1.72%) cases among first, second, and third-degree family members, respectively.

Work-related exposure to chemicals (cement, rubber, plastics, and fertilizers) was significantly more common among vitiligo than in controls (P < 0.05) [Table 2].

Hypothyroidism was significantly more common among cases (10.52%) than in controls (5.35%) and among females (14.98%) than in males (5.06%). Positive anti-TG antibodies were significantly more common in patients with vitiligo than in controls (P = 0.025) [Tables 2 and 3].

Obesity was significantly less common among vitiligo [Table 2]. Prevalence of diabetes (both type 1 and 2) was not significantly different between cases and controls or between males and females (P > 0.05) [Tables 2 and 3]. There was no association between vitiligo and response to antidiabetic treatment.

A feeling of depressed mood among vitiligo patients aged 10 years and above was found to be three times more common than that among controls [P < 0.001, OR 3.10 (95% CI-2.70-3.56)]. A significantly higher number of females had depressed mood due to their vitiligo [P < 0.001, OR, 1.49, (95% CI - 1.28-1.75)] [Tables 2 and 3]. Patients with vitiligo were found to have a higher tendency to skip school and other social gatherings, and a higher prevalence of suicidal ideas compared to the controls [Table 2]. However, no gender difference was noted on this parameter among the vitiligo cases [Table 3].

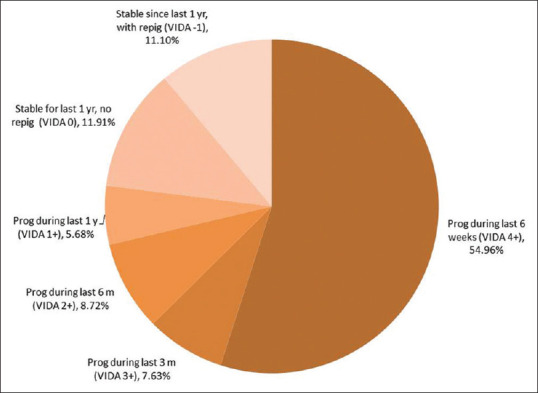

About 77% of all cases were unstable during the last 1 year as per VIDA scoring. Stable disease along with signs of repigmentation within the last 1 year was seen in 11.10% of all cases [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Distribution of stability assessed with VIDA scoring among cases (prog- progressive, repig = repigmentation, the number in bracket indicates VIDA scores)

Most common type of vitiligo was non-segmental vitiligo (NSV) (n = 2690, 67.89%) followed by focal (n = 977, 24.66%). Segmental vitiligo (SV) (n = 257, 6.49%) and mixed vitiligo (MV) (n = 38, 0.96%) were found in much less number of cases.

Most cases (n = 2815, 76.77%, excluding SV and MV cases) had less than 10% body surface area (BSA) involvement. Involvement of BSA of 10–<50%, 50–90% and >90% were found among 19.14%, 2.92% and 1.17% cases, respectively.

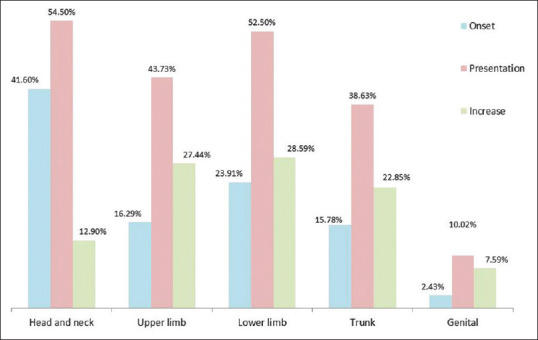

Head–neck region was the most commonly affected initial site of involvement (n = 1,648, 41.6%) and also during presentation (n = 2186, 55.17%) across all clinical types. However, the lower limb was the most commonly affected region among NSV cases [Figure 4]. The involvement of lip was more common (18.78%) than the acral areas (13.49%) and genitals (10.02%).

Figure 4.

Distribution of rates of involvement of different regions with vitiligo at the onset, at presentation, and the change with time. At presentation, multiple regions were simultaneously affected

Among all vitiligo cases, 59.24% (n = 2347) underwent some form of treatment in the past. Majority of them had undergone allopathic treatment (n = 1748, 74.49%) as the sole treatment or combined with other modalities. Ayurvedic and homeopathic treatments were utilized by 16.96%, (n = 393) and 17% (n = 394) cases, respectively. Among cases who were treated with any form of treatment in the past, a 'good' to 'satisfactory' response to previous treatment was reported by 28.05% (n = 658) cases. 'Unsatisfactory response' and 'progression despite treatment' were reported by 32.22% (n = 755) and 18.5% (n = 434) patients, respectively. Other patients either reported 'no response' or could not properly evaluate the past treatment response.

Discussion

With its approximately 1.3 billion population, India is the second most populous country. It is also the seventh largest country in the world. India is a country of great ethnic diversity and skin color. This pan-Indian study provided us a unique opportunity to assess vitiligo among a widely variable sample with diverse geographical, environmental, racial and social factors.

This survey is possibly the largest among all institutional surveys.[7] In fact, only two other surveys have a larger sample size than this and both were population-based surveys.[8,9]

To maintain the homogeneity of the selecting centers, only medical colleges were included as these cater a wide and diverse section of the population.

As per various population surveys from Greece,[10] Denmark,[11] Egypt,[12] and USA[13] relative prevalence was found to be 0.5%, 0.38%, 1.2%, and 0.1%, respectively. A recently published meta-analysis that evaluated population as well as hospital-based studies published from many continents like Asia, Africa, USA, Europe, Oceania, and Atlantic (Faroe Islands) reported a pooled population prevalence rate of 0.1% (0.1– 0.2%) in Asia, 0.4% (0.1– 0.7%) in Africa, 0.2% (0.1–0.4%) in America, 0.4% (0.2–0.5%) in Europe and 0.1% (0–0.1%) in Atlantic.[7] The same meta-analysis found the hospital-based prevalence to be 1.6% in Asia, 2.5% in Africa, and 1.5% in America. In another multicountry review, the prevalence of vitiligo was reported to vary from 0.06% to 2.28%.[14] A decreasing prevalence rate of vitiligo worldwide was also reported.[7]

Some of the previous publications from India revealed the prevalence of vitiligo from 0.6% to 1.13% [mean 1.1 ± 0.68] in the population-based surveys.[2,15,16,17] Among the hospital-based surveys,[18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26] the range was wider [0.43%-9.98%, mean 2.96 ± 0.99]. Overall prevalence was 2.512± 0.49 [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparative epidemiological profiles in previous Indian studies on vitiligo

| First author, publication year | Study type | Case types and Selection Method | Types of samples | Sample size, number of cases and duration of case selection | Geographical areas | Prevalence of vitiligo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dogra S et al. 2003[15] | Controlled, observational | Children (age- 6 to14 years) Cases from school and control from hospital Vitiligo was among many other skin diseases evaluated |

Population (School survey) | Sample size- 12,586 cases-272 Control-173 |

Chandigarh, | 2.2% |

| Bhatia V, 1997[16] | Uncontrolled, observational | Children (age group 0-14 years) | Population | Sample size-666 Cases-4 Duration-one year (1988-1989) |

Wardha, Maharastra | 0.6% |

| Das SK et al. 1985[2] | Uncontrolled Observational Two phased study |

All cases (in the first phase) and all new cases in the institutional phase | 1st phase- population (educational institutes and 3 areas) 2nd phase- institutional (single centre) |

1st phase -Sample size-15,685 Cases-72 Duration-unknown 2nd phase- Sample size- unknown Case-293 Duration-4 years (November, 1978, to December, 1982) |

Kolkata, West Bengal | 0.46% (1st phase) |

| Mehta NR et al. 1973[17] | Uncontrolled, Observational | All new cases | Population | Sample size-9065 Vitiligo-138 Duration 1 year (1971-1972) |

Surat, Gujarat | 1.13% |

| Mahajan VK et al. 2019[18] | Retrospective, Uncontrolled observational | All cases from old medical records | Institutional (single centre) | Sample size-2,17,518- Cases-945 Duration-5 years (2013-2017) |

Tanda, Himachal Pradesh | 0.43% |

| Dimri D et al., 2016[19] | Uncontrolled, Observational | All new cases (Vitiligo was among many other skin diseases evaluated) |

Institutional (single centre) | Sample size- 47465 Cases-1582 Duration 6 years, 2009 to 2014 |

Garhwal region, Uttarakhand | 3.3% |

| Agarwal S et al. 2014[20] | Uncontrolled observational, | All new cases | Institutional (single centre) | Sample size-28,842 Cases 762 Duration-5 years (2006-2010) |

Kumaun, Uttarakhand | 2.64% |

| Vora R et al. 2014[21] | Uncontrolled observational | All new cases | Institutional (single centre) | Sample size-Unknown Cases-1010 Duration-1 year |

Gujarat | Unknown |

| Kumar S et al. 2012[22] | Uncontrolled Observational |

All cases of vitiligo | Institutional (4 centres) | Sample size-443 Cases-44 A single day (20 November 2012) |

Delhi, Odisha, Mahabbubnaga, Mumbai | 9.98% |

| Poojary S 2011[23] | Retrospective Uncontrolled Descriptive |

All cases of vitiligo (from old medical record from vitiligo clinic) | Institutional (single centre) | Sample size-33252 Cses-204 Duration 6 years (2002-2008) |

Mumbai, Maharastra | 0.61% |

| Shah H et al. 2008[24] | Uncontrolled Observational |

All new cases | Institutional (single centre) | Sample size-unknown Cases-365 Duration-5-years (2001 to 2006) |

Bhavnagar, Gujarat | 1.84% |

| Dogra S et al. 2005[25] | Retrospective, Uncontrolled, observational | Cases with onset after 50 years of age (from old medical record in pigmentary clinic) | Institutional (single centre) | Sample size- 112 785 Cases- 182 Duration- 10 years (1990-99) |

Chandigarh | 2.4% |

| Handa S et al. 1999[26] | Uncontrolled, observational | All vitiligo patients | Institutional (single centre) | Sample size-57,630 Cases-1436 Duration- 4 and half years (1989-1993) |

Chandigarh | 2.5% |

All the four previous population surveys in India were conducted in some selected areas of single districts (Kolkata, Wardha, Chandigarh, and Surat). Among these, two studies were done only on children[15,16] and another one was not focused on vitiligo and surveyed many other dermatoses.[17]

The only multicentric study done in India actually surveyed hospital attendance of vitiligo cases on a single day (November 20, 2012) in all the centers.[22] Moreover, it was an uncontrolled observation, the total sample size was 443, total vitiligo cases were 44. Single-day point prevalence was reported to be 9.98%.

The study in Tanda, Himachal Pradesh was retrospective in nature and evaluated 2,17518 samples from the hospital records (5-year period) and total of 945 vitiligo cases were obtained.

The present study was conducted simultaneously in 30 centers widely distributed across 21 Indian states among 4,43,275 clinic attendees. The total sample size was 7,924 (with an equal number of vitiligo and control cases). This pan-Indian survey, as per our knowledge, is thus the largest Indian survey on vitiligo and covered wide geographical areas.

We found a significantly higher prevalence of vitiligo among females (0.93%) than in males (0.86%) (P < 0.001). Female preponderance was also reported in earlier studies from Rome,[27] Tunisia,[28] India (Gujarat)[22], and in some of the worldwide pooled data.[7] Studies conducted in Chandigarh, India[15] and Gujarat, India,[17] however reported a male preponderance, whereas no difference in sex distribution was found in a study from Kolkata, India.

Mean 'age at onset' was reported to be within the first three decades in studies by Zhanget et al.[29] and Boisseau-Garsaudet et al.[30] and in two institutional surveys from India.[21,26] We found a nearly similar result [25.14 ± 7.48 years (1 month to 82.5 months)]. In one Chinese study,[31] the median age at onset was 37.6 years. Ezzedine et al.[32] reported that most populations have mixed age-at-onset groups and have double peaks. One hospital-based survey in Saudi Arabia reported a much younger age at onset (17.4 year).[33]

We found that attendance in hospitals progressively decreased with the age of the patient. A similar observation was also made in an institutional study from Rome.[27]

Family history was found to be very high among the people of Saudi Arabia. One institutional study[33] and another one among vitiligo probands[34] from Saudi Arabia reported the prevalence of positive family history to be 42.8% and 56.8%, respectively. We found a prevalence rate of 11.31% and this is close to another study from China (9.8%). Two earlier Indian studies, both from Gujarat reported much higher rates (20.4% and 78.29%).[17,21]

Two earlier reports, one from India[26] and one from China[31] reported a higher prevalence of positive family history among SV cases. We, however, found significantly higher value in NSV.

We evaluated the prevalence of consanguinity in vitiligo cases (7.14%) and this was significantly higher than that in the control.

We elicited that the prevalence of thyroid disorders was significantly higher in vitiligo patients in comparison to the control. Additionally, positive anti-TPO and anti-TG antibodies were higher among vitiligo patients than in control. This is also in concurrence with previous studies.[9,23,35]

Similar to studies by Chen et al.[9] and Silva de Castro et al.,[35] we found that the prevalence of diabetes mellitus, both type 1 and type 2, was not significantly associated with vitiligo.

Similar to earlier studies by Silverberg et al.[36] and Dolatshahi et al.[37] we have found a significantly higher prevalence of depressed mood and psychosocial impact of the disease among patients than in control. In contrast to the study by Karelson,[38] however, we could not find any difference in the prevalence of this variable between males and females.

There is increasing evidence suggesting an intimate association between exposure to chemicals and the development of vitiligo.[39,40] We found a significant relationship between the development of vitiligo and work-related exposure to various chemicals.

In corroboration with most previous reports, NSV was found to be the most common clinical type of vitiligo in our study. The primary sites of disease development were reported to be the face, lower limb, and upper limb in earlier studies.[21,28,41,42] Head–neck region was the most common initial site as well as the most commonly involved site at presentation across all clinical types of vitiligo. However, among patients with NSV, the lower limb was more commonly affected. It was interesting to find that lips were involved in more cases than acral areas (13.49%).

We noted that a significant section of vitiligo patients availed alternative therapies like Homeopathic and Ayurvedic treatment at some point in time. We could not find studies to compare our findings.

This study has some limitations. Due to limitations in fund, investigations were not kept as mandatory. Some recall bias was also anticipated among the subjects as the study questionnaire required recall of past events. The inherent problem of all institution-based surveys, including this one is that the sample might not exactly represent the population.

Conclusion

In conclusion despite some unavoidable limitations, the essence of this study was it's strict adherence to the protocol, proper methodology, sex and age-matched control group, uniform nature of the centers with pan-Indian extent, enormous study population from the diverse geographical, social, economic, racial, cultural, and occupational background. We expect the results will serve as an authentic reference for all future studies.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study has been provided with an academic grant from the Indian Association for Dermatologists, Venereologists, and Leprologists (IADVL).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the sincere efforts of the following contributors. All authors and contributors were part of the MEDEC-V team and actively participated in the study.

Angoori Gnaneshwar Rao, SVS Medical College, Telangana; Bikash Ranjan Kar, IMS and SUM Hospital, Odissa; Dinesh Prasad Asati, AIIMS, Madhya Pradesh; Farah Sameem, SKIMS MCH, J&K; Gautam Mazumder, Tripura Medical College and Dr Bram Teaching Hospital, Tripura; Iffat Hasan, Govt. Medical College, J&K; Kapil Dev Das, Malda Medical College, West Bengal; Mithuvel Kumarsan, Cutis Skin Clinic, Tamil Nadu; Patnala Guruprasad, Andhra Medical College, Andhra Pradesh; Ranjan C Raval, GCS Medical College, Gujarat; Shrenik Balegar, Skin City, Pune; Tarang Goyal, Muzaffarnagar Medical College, Uttar Pradesh; Vani Talluru, Guntur Medical College, Andhra Pradesh; Vikas Shankar, Nalanda Medical College and Hospital, Bihar; Vikram Mahajan, Dr. Rajendra Prasad Govt. Medical College, Himachal Pradesh; Vivek Kumar Dey, People's College of Medical Sciences and Research Center, Madhya Pradesh.

References

- 1.Hann SK, Nordlund JJ. Definition of vitiligo. In: Hann SK, Nordlund JJ, editors. Vitiligo. 2nd ed. New Jersey: Blackwell Science; 2000. pp. 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Das SK, Majumder PP, Majumdar TK, Haldar B. Studies on vitiligo.II Familial aggregation and genetics. Genet Epidemiol. 1985;2:255–62. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1370020303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alkhateeb A, Fain PR, Thody A, Bennett DC, Spritz RA. Epidemiology of vitiligo and associated autoimmune diseases in Caucasian probands and their families. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:208–14. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0749.2003.00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaturvedi SK, Singh G, Gupta N. Stigma experience in skin disorders: An Indian perspective. Dermatol Clin. 2005;23:635–42. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mattoo SK, Handa S, Kaur I, Gupta N, Malhotra R. Psychiatric morbidity in vitiligo: Prevalence and correlates in India. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:573–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2002.00590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ezzedine K, Lim HW, Suzuki T, Katayama I, Hamzavi I, Lan CCE, Goh BK, et al. Revised classification/nomenclature of vitiligo and related issues: the Vitiligo Global Issues Consensus Conference. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2012;25:E1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2012.00997.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Cai Y, Shi M, Jiang S, Cui S, Wu Y, et al. The prevalence of vitiligo: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0163806. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee H, Lee MH, Lee DY, Kang HY, Kim KH, Choi GS, et al. Prevalence of vitiligo and associated comorbidities in Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2015;56:719–25. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2015.56.3.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen YT, Chen YJ, Hwang CY, Lin MW, Chen TJ, Chen CC, et al. Comorbidity profiles in association with vitiligo: A nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1362–9. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kyriakis KP, Palamaras I, Tsele E, Michailides C, Terzoudi S. Case detection rates of vitiligo by gender and age. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:328–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.03770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howitz J, Brodthagen H, Schwartz M, Thomsen K. Prevalence of vitiligo.Epidemiological survey on the Isle of Bornholm, Denmark. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:47–52. doi: 10.1001/archderm.113.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdel-Hafez K, Abdel-Aty MA, Hofny ERM. Prevalence of skin diseases in rural areas of Assiut Governorate, Upper Egypt. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:887–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Serag HB, Hampel H, Yeh C, Rabeneck L. Extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C among United States male veterans. Hepatology. 2002;36:1439–45. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.37191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krüger C, Schallreuter KU. A review of the worldwide prevalence of vitiligo in children/adolescents and adults. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1206–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dogra S, Kumar B. Epidemiology of skin diseases in school children: A study from northern India. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20:470–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2003.20602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhatia V. Extent and pattern of paediatric dermatoses in rural areas of central India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1997;63:22–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehta NR, Shah KC, Theodore C, Vyas VP, Patel AB. Epidemiological study of vitiligo in Surat area, South Gujarat. Indian J Med Res. 1973;61:145–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahajan VK, Vashist S, Chauhan PS, Mehta KIS, Sharma V, Sharma A. Clinico-epidemiological profile of patients with vitiligo: A retrospective study from a tertiary care center of North India. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019;10:38–44. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_124_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dimri D, Reddy BV, Singh AK. Profile of skin disorders in unreached hilly areas of North India. Dermatol Res Pract. 2016;2016:8608534. doi: 10.1155/2016/8608534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agarwal S, Ojha A, Gupta S. Profile of vitiligo in Kumaun region of Uttarakhand, India. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:209. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.127706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vora RV, Patel BB, Chaudhary AH, Mehta MJ, Pilani AP. A clinical study of vitiligo in a rural set up of Gujarat. Indian J Community Med. 2014;39:143–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.137150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar S, Nayak CS, Padhi T, Rao G, Rao A, Sharma VK, et al. Epidemiological pattern of psoriasis, vitiligo and atopic dermatitis in India: Hospital-based point prevalence. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5(Suppl 1):S6–8. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.144499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poojary SA. Vitiligo and associated autoimmune disorders: A retrospective hospital-based study in Mumbai, India. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2011;39:356–61. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shah H, Mehta A, Astik B. Clinical and sociodemographic study of vitiligo. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:701. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.45144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dogra S, Parsad D, Handa S, Kanwar AJ. Late onset vitiligo: A study of 182 patients. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:193–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.01948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Handa S, Kaur I. Vitiligo: Clinical findings in 1436 patients. J Dermatol. 1999;26:653–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1999.tb02067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paradisi A, Tabolli S, Didona B, Sobrino L, Russo N, Abeni D. Markedly reduced incidence of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer in a nonconcurrent cohort of 10,040 patients with vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1110–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akrem J, Baroudi A, Aichi T, Houch F, Hamdaoui MH. Profile of vitiligo in the south of Tunisia. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:670–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang XJ, Liu JB, Gui JP, Li M, Xiong QG, Wu HB, et al. Characteristics of genetic epidemiology and genetic models for vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boisseau-Garsaud AM, Garsaud P, Calès-Quist D, Hélénon R, Quénéhervé C, Claire RC. Epidemiology of vitiligo in the French West Indies (Isle of Martinique) Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:18–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X, Du J, Wang T, Zhou C, Shen Y, Ding X, et al. Prevalence and clinical profile of vitiligo in China: A community-based study in six cities. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:62–5. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ezzedine K, Thuaut AL, Jouary T, Ballanger F, Taieb A, Bastuji-Garin S. Latent class analysis of a series of 717 patients with vitiligo allows the identification of two clinical subtypes. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:134–9. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alissa A, Al Eisa A, Huma R, Mulekar S. Vitiligo-epidemiological study of 4134 patients at the National Center for Vitiligo and Psoriasis in Central Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2011;32:1291–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alzolibani A. Genetic epidemiology and heritability of vitiligo in the Qassim region of Saudi Arabia. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2009;18:119–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silva de Castro CC, do Nascimento LM, Olandoski M, Mira MT. A pattern of association between clinical form of vitiligo and disease-related variables in a Brazilian population. J Dermatol Sci. 2012;65:63–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Association between vitiligo extent and distribution and quality-of-life impairment. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:159–64. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dolatshahi M, Ghazi P, Feizy V, Hemami MR. Life quality assessment among patients with vitiligo: Comparison of married and single patients in Iran. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:700. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.45141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karelson M, Silm H, Kingo K. Quality of life and emotional state in vitiligo in an Estonian sample: Comparison with psoriasis and healthy controls. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:446–50. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harris JE. Chemical-Induced Vitiligo. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:151–61. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bonamonte D, Vestita M, Romita P, Filoni A, Foti C, Angelini G. Chemical Leukoderma. Dermatitis. 2016;27:90–9. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Barros JC, Machado Filho CD, Abreu LC, de Barros JA, Paschoal FM, Nomura MT, et al. A study of clinical profiles of vitiligo in different ages: An analysis of 669 outpatients. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:842–8. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arýcan Ö, Koç Ö, Ersoy L. Clinical characteristics in 113 Turkish vitiligo patients. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2008;17:129–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]