Abstract

Objectives:

We conducted a policy scan of state and local laws and policies across the United States related to social determinants of health among immigrants.

Methods:

We collected all state and municipal laws and policies in 10 domains that had potential to affect immigrant health from all 50 U.S. states and the 30 most populous U.S. metropolitan statistical areas. We coded these laws and policies and created an index of restrictiveness and supportiveness of immigrants.

Results:

We identified 539 state and 322 municipal laws and policies. The most common restrictive state laws and policies were in the domains of identification requirements and driver’s license access. The most common supportive state laws and policies were in the domains of health services and higher education access. The most common restrictive municipal laws and policies were in the domains of identification requirements and immigration policy enforcement. The most common supportive municipal laws and policies were in the domains of immigration policy enforcement and health services access.

Conclusions:

Most states had index scores reflecting policy environments that were primarily restrictive of immigrants, indicating potential negative impacts on social determinants of health. Further research examining the impact of these on health behaviors is warranted.

Keywords: Immigrant, law, policy, state, local, social determinants of health

State and local laws and policies may disproportionately affect marginalized populations, such as immigrants, and result in adverse health outcomes. There is a growing body of research suggesting that laws and policies related to immigration may have a significant influence on these individuals seeking and receiving a variety of health services.1-3 For example, previous research indicates that laws, such as section 287(g) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, Secure Communities, and laws regarding eligibility for driver’s licenses may reduce access to, and utilization of, needed health services among immigrant Latinx persons and consequently increase morbidity and mortality.4,5 Some laws and policies may directly affect health disparities by reducing access to prevention, screening, and treatment services. However, others may do so indirectly, through their influence on social determinants of health, such as education, employment, housing, social support, or trust in community institutions such as law enforcement.6-9

There is a pressing need to explore and elucidate links between state and local laws and policies relevant to immigrant populations and important public health outcomes, particularly those related to health disparities. For example, state and local laws and policies may be related to disproportionately high rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), unintended pregnancy, alcohol consumption, and smoking among marginalized populations, including immigrants and their children.10

While immigration-related laws and policies exist at the federal, state, and local levels, most health policy research attention has focused on the impact of only federal immigration laws and policies.11,12 This is a consequential omission for several reasons. First, in the U.S. immigration system, immigrant integration policy is entrusted mostly to the states and localities while the federal government has primary control over admissions and deportation policies.13 This means that states and localities have a primary role in making immigrant-related laws and policies in domains such as education, employment, welfare, health care, child care, licensing (driving and professional licenses), and language facilitation, to name a few. Second, since the September 2011 attacks on the United States, some states and localities have also become involved in immigration enforcement and deportation by cooperating with federal immigration officials in the identification and removal of noncitizens.4,14,15 This cooperation goes beyond those who commit crimes, to include those merely stopped for suspicion, or even with no probable cause.1 Third, in part as a result of political polarization and stalled immigration reform at the federal level,16 the number of state-level immigrant-related laws has increased substantially since the early years of the twenty-first century. Both states and local municipalities (counties and cities) have been much more active in adopting laws and policies that might negatively or positively affect immigrant health.17, 18 This variation across jurisdictions and over time provides an important opportunity for researchers and practitioners to assess the effects state and local laws and policies may have on a range of public health outcomes.

Previously, however, a major barrier to such research has been a lack of accurate and systematic specification of state and local laws and policies that potentially affect immigrant health. Researchers have studied proposed laws and policies,1, 4 but documentation of enacted laws and policies has not been systematic. We sought to identify immigrant-related state and local laws and policies that may affect social determinants of health through a systematic policy scan; code these laws and policies in terms of restrictiveness and supportiveness of immigrants; develop an index score reflecting the overall policy environment of each U.S. state; and create a publically available summary dataset to facilitate further immigration-related public health research.

METHODS

A policy scan systematically gathers and analyses policies on a particular area of interest.19 As a first step of this scan, we reviewed peer-reviewed and “gray” background literature to identify the range of immigrant-related laws and policies that could be relevant to public health and to obtain previous compilations of relevant state or local laws and policies (eg, http://www.ncsl.org/research/immigration/state-laws-related-to-immigration-and-immigrants.aspx).1 Based on this review and in consultation with policy researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), we identified ten substantive domains of state and local laws and policies that potentially could affect the health of immigrants and immigrant communities:

Access to health services for immigrants (Health Services Access)

Employment of immigrants in a broad segment of the private sector (Private-Sector Employment)

Business licensing for immigrants in a broad segment of the private sector (Business Licensing)

Access to rental housing for immigrants (Rental Housing Access)

Access to higher education for immigrants (Higher Education Access)

Access to driver’s licenses for immigrants (Driver’s License Access)

Cooperation by state or local law enforcement with federal immigration enforcement (Immigration Policy Enforcement)

Use of non-English language in health services, education, or a broad range of government and public services that potentially include health services (Non-English Language Use)

Identification requirements to access health services, education, housing, employment, or a broad range of government and public services that potentially include health services (Identification Requirements)

Prohibition of discrimination based specifically on citizenship or immigration status in health services, education, housing, employment, or in a broad range of public services that potentially include health services (Discrimination Prohibition)

We used established best practices19, 20 to identify and code laws and policies that were in effect as of January 2016 and were relevant to these ten domains in U.S. states and in municipalities comprising the 30 most populous metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) in the U.S. based on U.S. Census data as of June 2016 (www.census.gov).

Identifying and Coding Municipal Laws and Policies

Five Wake Forest University law students were trained by members of the project team to identify and code laws and policies at the municipal (county/city) level. The coders first conducted database and internet searches in June 2016 to identify all potential laws and policies of interest in all selected municipalities (all 273 counties within the 30 most populous MSAs, and all 28 cities that accounted for more than half of the population in each of these counties). The coders used several specialized databases: LexisNexis, MuniCode, eCode, and American Legal Publishing. Searches for municipal laws and policies were supplemented with web searches at municipal websites located primarily through the National Association of Counties website (https://www.naco.org/). The following search terms were used (including relevant word extensions):

alien, immigrant, immigration, nonimmigrant, citizenship, noncitizen, noncitizen, nonresident, undocumented, lawfully present, lawful permanent, legally present, legal presence, legal resident, legal residence, lawful presence, lawfully residing, lawful resident, migrant, PRUCOL, foreign-born, official language, non-English, Spanish, translator, interpreter, unauthorized worker, foreign passport, deport, detain, E-verify, social security number, foreign birth certificate, consular

Where no online information was available for a municipality, coders contacted the municipal government directly to obtain copies of laws or policies that were relevant to our search terms.

The coders then reviewed the full text of enacted laws and policies identified by these searches to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria for any of the ten domains of interest. Within each domain, they abstracted and coded summary information, including jurisdiction, effective date, type of law/policy, and legal citation, for each identified law or policy; whether it was restrictive or supportive of immigrants; and categories of immigrants it targeted, such as legal permanent resident, temporary status holder, and/or undocumented.

For each included law or policy, data were captured, coded, and managed via REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), a secure web application for building and managing online surveys and databases. To ensure reliability, two different coders were randomly assigned to review and code each law or policy separately. The two coders assigned to each law or policy then conferred with one another to resolve any discrepancies in coding. In the few instances in which they were unable to come to consensus about a coding discrepancy, two members of the project team with legal expertise determined the final coding for that particular law or policy.

Laws and policies were identified for all included cities, but no laws or policies could be located for 58 included counties. For the most part, these were smaller, outlying counties; some states had a greater concentration of counties for which laws were not available. For example, no laws or policies were available in 18 of 34 counties in Texas, 8 of 17 counties in Missouri, and 5 of 10 counties in Ohio. Furthermore, no laws or policies were available in most counties in Massachusetts and New Jersey; the relevant municipal authority in those two states is possessed by cities rather than counties. Based on our criterion of including only cities whose population was greater than half of their respective county’s, no New Jersey cities were included, and only Boston was included in Massachusetts.

In addition, some counties had some information available about their laws and policies online, but these online resources were not uniformly up-to-date. Thirty-nine counties had not updated their online information about their laws and policies since 2014. These less up-to-date counties were also scattered across different states, with six of them in Georgia. Laws in the remaining counties (as well as all selected cities) appeared to be up-to-date.

Because policies related to cooperation by local law enforcement with federal immigration enforcement are not likely to be reflected in formal laws, relevant legal policies were identified using information compiled from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (https://www.ice.gov/287g) and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (https://www.uscis.gov/save/save-agency-search-tool). These policies were coded by the project team member with the most legal expertise (M. Hall), following the same guidelines used by the other coders.

Identifying and Coding State Laws and Policies

State laws and policies were initially identified and coded by researchers at the University of Illinois at Chicago and the University of Rhode Island. The State-Level Immigration Policy Bills and Enactments Database (SIPD) was developed using LexisNexis to identify all immigration-related bills introduced in state legislatures from 1990 through 2015.21 Trained coders followed coding instructions that captured as much detail as was specified in the coding protocol that we independently created for municipal laws and policies. Coders double coded approximately nine percent of bills to assess reliability of coding. Cross-coder reliability ranged between 85% and 93% depending on the number of coding conditions included in the metrics.

Limiting the SIPD to state data that reflected enacted bills (ie, laws or policies) as opposed to introduced bills for the current study, we recoded these laws and policies according to the municipal law and policy coding protocol. When SIPD coded data were ambiguous or did not satisfy logic checking, trained study team members reviewed the original law or policy or its official synopsis to determine its relevance and proper coding.

The SIPD was not used as the primary source for state laws and policies in three of the ten domains: health services access, driver’s license access, and immigration policy enforcement. Compilations by the Urban Institute (https://www.urban.org/features/state-immigration-policy-resource), the National Immigration Law Center (https://www.nilc.org/issues/health-care/; https://www.nilc.org/issues/drivers-licenses/; https://www.nilc.org/issues/immigration-enforcement/), and the Kaiser Family Foundation (http://www.kff.org/state-category/medicaid-chip/medicaidchip-eligibility-limits/) provided more accurate and targeted coding of laws and policies within these domains for our particular research purposes.

Information about state laws and policies from these compilations was cross-tabulated with the SIPD coding in order to maximize the amount of validated identifying information (eg, legal citation, effective date, and immigrant target group). State law and policy data coding was further reviewed to identify any additional state laws or policies of relevance in the three indicated domains not contained in these compilations. Conflicts between SIPD coding and these compilations were resolved by review of the original law or policy or its official synopsis. Cross-tabulation and verification was done by the project team member with the most legal expertise (M. Hall) according to the guidelines established in the municipal law coding protocol described above.

Policy Indexing

Policy researchers have used a series of strategies to create and validate policy indices.22-27 Many studies of U.S. immigration policy have generally employed simple count indices across multiple domains.28,29 Others have used simple counts but restricted to one or two specific domains which ensures more comparability30-32 or have created weighted index schemes that include a measure of the magnitude of the effect.33,34 Most studies that include multiple domains classify legislation as either “hostile” or “welcoming” to immigrants or a variation thereof that distinguishes between restrictive and supportive legislation.28,34-36 Others have focused only on restrictive laws.31,32 However, there is no clear guidance in the literature on whether these dimensions should be conceptualized and analyzed separately, or included in models as distinct independent variables. Also unsettled is whether different types of laws should be combined as a single measure, such as netting the difference between restrictive and supportive counts, or as a ratio, such as restrictive over supportive, or restrictive as a proportion of total. Recent analyses suggests that such decisions have important implications for the results.34,37

In this study, laws and policies were summarized by indexing each jurisdiction (state or municipality) according to whether, in each of the ten domains, laws and policies were restrictive of immigrants, supportive, both, or neither. Existing research on immigration law employs both discrete single item and index-based approaches.29,33,38 We based our index development on previous classifications by Monogan (2013) and other analysts of immigration laws and policies as either hostile or welcoming to immigrants. If a state or municipality had a restrictive law or policy (or multiple restrictive laws or policies) in a domain, it received a domain score of 1. If it had a supportive law or policy (or multiple supportive laws or policies) in that domain, it received a domain score of −1. If it had both restrictive and supportive laws or policies in the same domain, or no laws or policies in that domain, it received a domain score of 0. We then summed the domain scores to generate an overall index score for each state.

Correlations

We also identified correlations across domains. We used the standard criterion of 0.4 and above to identify which correlations are relatively strong.39

RESULTS

We identified a total of 539 state and 322 municipal laws and policies across the ten domains. Organized by jurisdiction, these laws and policies existed in every state and 70 of the 301 included municipalities. Of the 861 total state and municipal laws and policies found, effective or enacted dates could be determined for 608 (71%) of them. The remaining 253 were determined simply to still be in effect in 2016, with an uncertain enactment date.

The most common restrictive laws and policies at the state level were within the domains of identification requirements (47 states), driver’s license access (36 states), and private-sector employment (23 states) (see Table 1). The most common supportive state laws and policies were within the domains of health services access (39 states) and higher education access (24 states).

Table 1.

Number of States with Restrictive and Supportive Laws by Domain (N = 50)

| Domain | No Law | Restrictive Law Only |

Supportive Law Only |

Both Supportive & Restrictive Law |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Services Access | 10 | 1 | 29 | 10 |

| Private-Sector Employment | 24 | 22 | 3 | 1 |

| Business Licensing | 42 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Rental Housing Access | 48 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Higher Education Access | 18 | 8 | 18 | 6 |

| Driver's License Access | 10 | 28 | 4 | 8 |

| Immigration Policy Enforcement | 34 | 12 | 4 | 0 |

| Non-English Language Use | 32 | 5 | 9 | 4 |

| Identification Requirements | 3 | 41 | 0 | 6 |

| Discrimination Prohibition | 48 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

At the municipal level, the most common restrictive laws and policies were within the domains of identification requirements (25 municipalities) and immigration policy enforcement (19 municipalities) (see Table 2). The most common supportive municipal laws and policies were also within the domains of immigration policy enforcement (11 municipalities), followed by health services access and non-English language use (8 municipalities each).

Table 2.

Number of Municipalities with Restrictive and Supportive Laws by Domain (N = 301)

| Domain | No Law | Restrictive Law Only |

Supportive Law Only |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health Services Access | 293 | 0 | 8 |

| Private-Sector Employment | 297 | 2 | 2 |

| Business Licensing | 299 | 2 | 0 |

| Rental Housing Access | 298 | 0 | 3 |

| Higher Education Access | 301 | 0 | 0 |

| Driver's License Access | 301 | 0 | 0 |

| Immigration Policy Enforcement | 271 | 19 | 11 |

| Non-English Language Use | 290 | 3 | 8 |

| Identification Requirements | 270 | 25 | 6 |

| Discrimination Prohibition | 294 | 0 | 7 |

Of 45 possible correlations across domains, only five relatively strong correlations were identified at the state level (Table 3). Laws and policies within the domain of driver’s license access were correlated with those within the domains of (1) identification requirements and (2) higher education access. Laws and policies within the domain of discrimination prohibition were correlated with those within the domains of (1) private-sector employment and (2) rental housing access. Finally, laws and policies within the domain of health services access were correlated with those within the domain of higher education access.

Table 3.

Correlation Matrices of Domains by State and Municipality

| State | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Services Access |

Private- Sector Employment |

Business Licensing |

Rental Housing Access |

Higher Education Access |

Driver’s License Access |

Immigration Policy Enforcement |

Non- English Language Use |

Identification Requirements |

Discrimination Prohibition |

|

| Health Services Access | 1.0 | |||||||||

| Private-Sector Employment | −0.02 | 1.0 | ||||||||

| Business Licensing | 0.25 | 0.00 | 1.0 | |||||||

| Rental Housing Access | 0.00 | 0.34* | 0.00 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Higher Education Access | 0.40* | 0.28* | 0.20 | 0.14 | 1.0 | |||||

| Driver’s License Access | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.40* | 1.0 | ||||

| Immigration Policy Enforcement | 0.03 | 0.36* | 0.27 | 0.37* | 0.30* | 0.35* | 1.0 | |||

| Non-English Language Use | 0.20 | −0.03 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.29* | 0.12 | 1.0 | ||

| Identification Requirements | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.26 | 0.01 | 0.43* | 0.23 | 0.23 | 1.0 | |

| Discrimination Prohibition | −0.21 | 0.47* | 0.08 | 0.51* | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.36* | 0.17 | 1.0 |

| Municipal | ||||||||||

| Health Services Access | 1.0 | |||||||||

| Private-Sector Employment | 0.18* | 1.0 | ||||||||

| Business Licensing | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.0 | |||||||

| Rental Housing Access | 0.19* | 0.58* | 0.00 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Higher Education Access | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||||

| Driver’s License Access | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| Immigration Policy Enforcement | 0.21* | 0.27* | 0.00 | 0.11* | NA | NA | 1.0 | |||

| Non-English Language Use | 0.53* | 0.15* | 0.00 | 0.17* | NA | NA | 0.12* | 1.0 | ||

| Identification Requirements | 0.16* | 0.18* | 0.24 | 0.23* | NA | NA | 0.18* | 0.13* | 1.0 | |

| Discrimination Prohibition | 0.25* | 0.38* | 0.01 | 0.43* | NA | NA | 0.22* | 0.22* | 0.17* | 1.0 |

p-value < .05; NA = Not applicable; no municipal laws were identified pertaining to the domains: higher education and driver’s licenses

Of 45 possible correlations across domains, only three relatively strong correlations were identified at the municipal level. Laws and policies within the domain of rental housing access were correlated to those within the domains of (1) private-sector employment and (2) discrimination prohibition. Laws and policies within the domain of health services access were correlated with those within the domain of non-English language use.

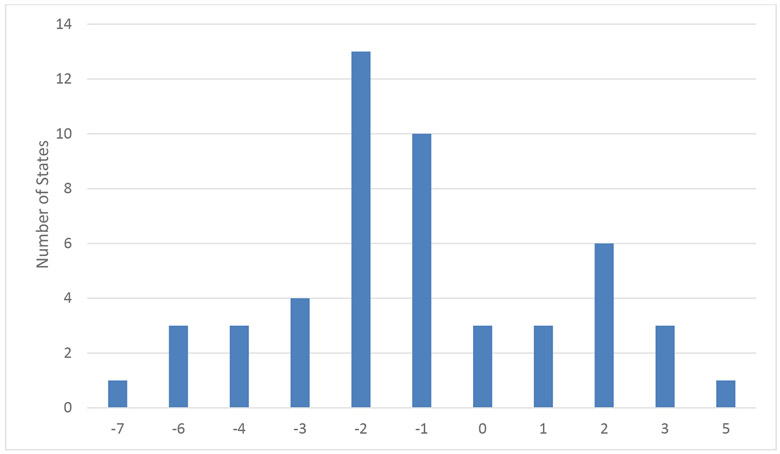

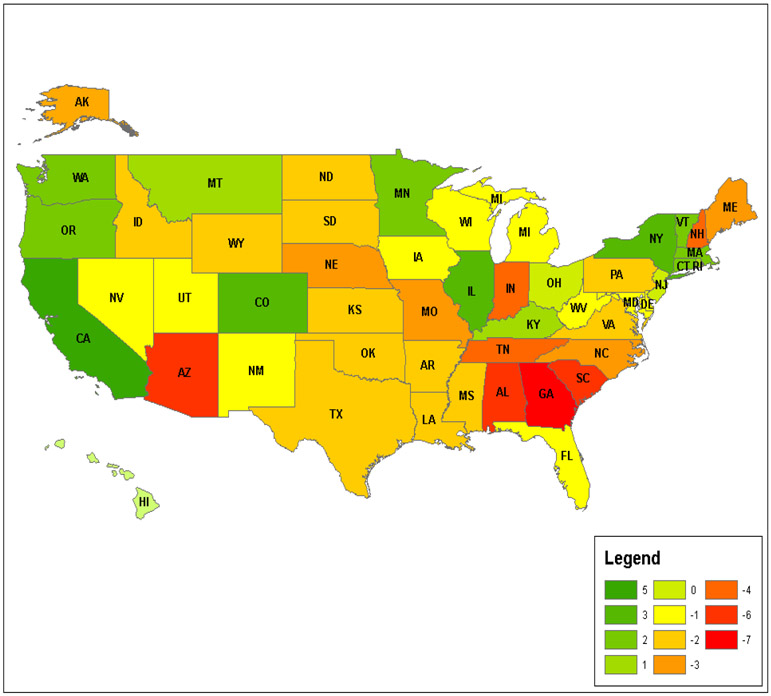

The majority of states (N = 34) had index scores of −1 or less (Figure 1), indicating policy environments that were primarily restrictive for immigrants. Three states had index scores of 0, indicating either equal presence of both restrictive and supportive laws or no laws being present. Thirteen states had index scores of 1 or greater, reflecting a policy environment that was supportive of immigrants. The geographic pattern of index scores across the U.S. states indicates more restrictive policy environments are concentrated in states in the South and Midwest and along the U.S.-Mexico border, and more supportive environments are concentrated on the West Coast and in the Northeast (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Index of State Laws Based on Restrictiveness and Supportiveness for Immigrants by Number of States.

Figure 2. State Immigration Policy Index Scores.

Note: Possible range = −10 to +10; higher scores = greater number of supportive laws and policies for immigrants

Indexing was not meaningful for municipalities, however, because most had no relevant laws or policies and only a few had multiple laws or policies.

DISCUSSION

In this policy scan, we identified, coded, and indexed state and local laws and policies that potentially affect immigrant health. In this process, some interesting patterns emerged. Overall, many states had immigrant-related laws and policies while municipalities had much fewer. In fact, all states had laws and policies in all domains, while municipalities had no laws or policies within the domains of higher education access or driver’s license access. This reflects the longstanding history of states dominating regulation in these domains.40,41

Furthermore, a majority of states had laws and policies related to five out of the ten domains, including health services access, private-sector employment, higher education access, driver’s license access, and identification requirements. Some of these states had both restrictive and supportive laws within the same domain. However, no municipality had both restrictive and supportive laws within the same domain. Potential explanations for why greater bifurcation was seen among municipalities may include the fact that municipalities may be more homogenous in their socio-political stances than entire states, or simply that municipalities have fewer relevant laws or policies than do states.

The pattern of state laws and policies rather than municipal laws and policies being predominant in the domains of discrimination prohibition, rental housing access, and immigration policy enforcement might be surprising, considering the controversy that has surrounded topics such as sanctuary cities and local anti-immigration policies.42 Although much of that controversy has focused on municipal laws and policies, our systematic review of 301 municipalities identified relatively few laws and policies. There are at least two explanations for this apparent discrepancy. First, at the local level, our objectives and data sources focused primarily on counties rather than cities, including the latter only when they accounted for more than half the county’s population. Second, our sample consisted of only the top 30 metropolitan areas. It may be that the more controversial local laws and policies have been adopted primarily by cities rather than counties, and, especially for restrictive laws, in less populous areas that were not included in our search.43

Another interesting finding was that nearly half of state and municipal laws and policies identified were enacted prior to 2006. Thus, despite the recent surge of interest in immigration policy, many of the laws and policies relevant to public health concerns went into effect well over a decade ago.42 Nevertheless, our search found a large number of laws and policies, at both the state and municipal levels, addressing all of the domains that we identified as potentially having an impact on immigrant health. It is also noteworthy that very few strong correlations were identified across domains. This suggests that states and localities often do not bring a comprehensive immigration policy perspective to bear when passing laws and policies related to different social determinants of health for immigrants.

IMPLICATIONS FOR HEALTH BEHAVIOR OR POLICY

State and local laws and policies may influence health behaviors and outcomes among immigrants. A comprehensive dataset that accurately specifies state and local laws and policies relevant to the health of immigrant populations has not previously existed, and the lack of such a dataset has been a significant barrier to assessment of the potential impact of laws and policies on the health of this particularly vulnerable population. Our summary review of this dataset, which is publically available, provides an initial picture of the content and variation of state and local laws and policies relating to health services access, private-sector employment, business licensing, rental housing access, higher education access, driver’s license access, immigration policy enforcement, non-English language use, identification requirements, and discrimination prohibition among immigrants.

This scan of immigration-related laws and policies lays groundwork to conduct further studies using this dataset, and researchers who are examining the role of state and local laws and policies in shaping public health will find it useful. Furthermore, because the impacts of laws and policies across domains likely differ, researchers should explore the various indexing methods of laws and policies. There remains a need for innovation in how laws and policies are indexed and how these indices can be used to inform policy decisions.

Building on our initial findings and the resulting dataset from this policy scan, researchers can use this dataset to more fully understand the ways in which state and local laws and policies affect immigrants’ lives and how they relate to specific public health outcomes such as STIs, unintended pregnancy, alcohol consumption, and smoking. Research is also needed to assess potential associations between state and local policy environments, or the presence or absence of specific restrictive and supportive immigrant-related laws and policies, and important and prioritized public health indicators such as those outlined in Healthy People 2020, including objectives related to access to health services and social determinants of health, in order to address the overarching 2020 goal to “achieve health equity, eliminate disparities, and improve the health of all groups.”44 Policymakers should then use this increased understanding in weighing the health-related costs and benefits of existing and proposed laws and policies. Finally, the ways in which laws and policies are implemented can also critically affect their impact and thus the role of implementation-related factors in influencing health behaviors and outcomes among immigrant populations also merits further consideration by practitioners.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this research was provided by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. All laws and policies included as part of this study, additional methods, and coded datasets are available from the authors.

Footnotes

Human Subjects Approval Statement

The Wake Forest School of Medicine Institutional Review Board reviewed this research and determined that it was exempt from further review.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Scott D. Rhodes, Department of Social Sciences and Health Policy, Wake Forest School of Medicine, and CTSI Program in Community Engagement, Winston-Salem, NC..

Lilli Mann-Jackson, Department of Social Sciences and Health Policy, Wake Forest School of Medicine, and CTSI Program in Community Engagement, Winston-Salem, NC..

Eunyoung Y. Song, Health Quality Partners, Doylestown Health, Doylestown, PA..

Mark Wolfson, Department of Social Medicine, Population, and Public Health, University of California, Riverside, School of Medicine, Riverside, CA..

Alexandra Filindra, Department of Political Science, University of Illinois, Chicago, IL..

Mark Hall, Wake Forest University School of Law and Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC..

References

- 1.Martinez O, Wu E, Sandfort T, et al. Evaluating the impact of immigration policies on health status among undocumented immigrants: A systematic review. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17(3):947–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hacker K, Anies M, Folb BL, et al. Barriers to health care for undocumented immigrants: A literature review. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2015;8:175–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Philbin MM, Flake M, Hatzenbuehler ML, et al. State-level immigration and immigrant-focused policies as drivers of Latino health disparities in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rhodes SD, Mann L, Simán FM, et al. The impact of local immigration enforcement policies on the health of immigrant Hispanics/Latinos in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):329–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mann L, Simán FM, Downs M, et al. Reducing the impact of immigration enforcement policies to ensure the health of North Carolinians: Statewide community-level recommendations. NC Med J. 2016;77(4):240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dean HD, Myles RL. Social determinants of sexual health in the USA among racial and ethnic minorities In Aral SO, Fenton KA, Lipshutz JA, (Eds). The New Public Health and STD/HIV Prevention: Personal, Public and Health Systems Approaches. New York, NY: Springer; 2013:273–292. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Filindra A, Blanding D, Garcia Coll C. The power of context: State-level policies and politics and the educational performance of the children of immigrants in the United States. Harv Educ Rev. 2011;81(3):163–193. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Academies of Sciences E, and Medicine, Health and Medicine Division, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, et al. Immigration as a Social Determinant of Health: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castaneda H, Holmes SM, Madrigal DS, et al. Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:375–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kline N When deservingness policies converge: U.S. immigration enforcement, health reform and patient dumping. Anthropol Med. 2019;26(3):280–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saunders J, Lim N, Prosnitz D. Enforcing Immigration Law at the State and Local Levels: A Public Policy Dilemma. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pham H The constitutional right not to cooperate - Local sovereignty and the federal immigration power. U Cin L Rev. 2006;74(4):1373–1413. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tichenor D, Filindra A. Raising Arizona v. United States: The origins and development of immigration federalism. Lewis Clark Law Rev. 2013;16(4):1215–1247. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Creek HM, Yoder S. With a little help from our feds: Understanding state immigration enforcement policy adoption in American federalism. Policy Stud J. 2012;40(4):674–697. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedroza JM. Deportation discretion: Tiered influence, minority threat, and “Secure Communities” deportations. Policy Stud J. 2019;47(3):624–646. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bulman-Pozen J Partisan federalism. Harv Law Rev. 2014;127(4):1078–1145. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pham H, Pham VH. Subfederal immigration regulation and the Trump effect. NYU L Rev. 2019;94:125–170. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morse A, Mendoza GS, Mayorga J. Report on 2015 State Immigration Laws. Washington, DC: National Conference of State Legislatures; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Presley D, Reinstein T, Burris SC. Resources for Policy Surveillance: A Report Prepared for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Law Program. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tremper C, Thomas SB, Wagenaar AC. Measuring law for evaluation research. Eval Rev. 2010;34(3):242–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Filindra A, Pearson-Merkowitz S. State-Level Immigration Policy Bills and Enactments Database. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois at Chicago; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bjerre L, Helbling M, Römer F, et al. Conceptualizing and measuring immigration policies: A comparative perspective. Int Mig Rev. 2015;49(3):555–600. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bjerre L, Römer F, Zobel M. The sensitivity of country ranks to index construction and aggregation choice: The case of immigration policy. Policy Stud J. 2019;47(3):647–685. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodman SW. Conceptualizing and measuring citizenship and integration policy: Past lessons and new approaches. Comp Political Stud. 2015;48(14):1905–1941. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodman SW. Indexing immigration and integration policy: Lessons from Europe. Policy Studies J. 2019;47(3):572–604. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Filindra A, Goodman SW. Studying public policy through immigration policy: Advances in theory and measurement. Policy Studies J. 2019; 47(3):498–516. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexander GR, Kotelchuck M. Quantifying the adequacy of prenatal care: A comparison of indices. Public Health Rep. 1996;111(5):408–418. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ybarra VD, Sanchez LM, Sanchez GR. Anti-immigrant anxieties in state policy: The Great Recession and punitive immigration policy in the American states, 2005–2012. State Politics Policy Q. 2016;16(3):313–339. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gelatt J, Bernstein H, Koball H. United the Patchwork:Measuring State and Local Immigrant Contexts. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Filindra A, Manatschal A. Coping with a changing integration policy context: American state policies and their effects on immigrant political engagement. Reg Stud. 2019:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hero R, Preuhs R. Immigration and the evolving American welfare state: Examining policies in the U.S. States. Am J Political Sci. 2007;51(3):498–517. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Filindra A Immigrant social policy in the American states: Race politics and state TANF and Medicaid eligibility rules for legal permanent residents. State Politics Policy Q. 2013;13(1):26–48. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monogan JE. The politics of immigrant policy in the 50 U.S. States, 2005–2011. J Public Policy. 2013;33(1):35–64. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monogan JE. Studying immigrant policy one law at a time. Policy Stud J. 2019;47(3):686–711. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Monogan JE. The politics of immigrant policy in the 50 U.S. states, 2005–2011. J Public Policy. 2013;33(01):35–64. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boushey G, Luedtke A. Immigrants across the U.S. federal laboratory: Explaining state-level innovation in immigration policy. State Politics Policy Q. 2011;11(4):390–414. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reich G One model does not fit all: The varied politics of state immigrant policies, 2005–16. Policy Studies J. 2019;47(3):544–571. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hero RE, Preuhs RR. Immigration and the evolving American welfare state: Examining policies in the US. Am J Political Sci. 2007;51(3):498–517. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akoglu H User’s guide to correlation coefficients. Turk J Emerg Med. 2018;18(3):91–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bjorklund P Undocumented students in higher education: A review of the literature, 2001 to 2016. Rev Educ Res. 2018;88(5):631–670. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Enriquez LE, Vazquez Vera D, Ramakrishnan SK. Driver’s licenses for all? Racialized illegality and the implementation of progressive immigration policy in California. Law Policy. 2019;41(1):34–58. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martinez-Schuldt RD, Martinez DE. Sanctuary policies and city-level incidents of violence, 1990 to 2010. Justice Q. 2017:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martínez-Schuldt RD, Martínez DE. Sanctuary policies and city-level incidents of violence, 1990 to 2010. Justice Q. 2019;36(4):567–593. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. U.S. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]