Abstract

Hypertension is a chronic condition that disproportionately affects African Americans. Managing high blood pressure (HBP) requires adherence to daily medication. However, many patients with hypertension take their HBP medication inconsistently, putting them at heightened risk of heart disease. Researchers have shown that these health risks are greater for African Americans than for Caucasians. In this article, we examine barriers and facilitators of medication adherence among urban African Americans with hypertension. We interviewed 24 African Americans with hypertension (58.5% women, average age 59.5 years) and conducted a comprehensive thematic analysis. Twenty-two barriers and 32 facilitators to medication adherence emerged. Barriers included side effects and forgetting while facilitators included reminders, routines and social support. Using this data, we developed a diagram of theme connectedness of factors that affect medication adherence. This diagram can guide multi-level HBP intervention research that targets African Americans to promote medication adherence, prevent heart disease, and reduce ethnic and racial health disparities.

Keywords: Hypertension, medication adherence, African Americans, minority health, health status disparities

Heart disease – including heart attacks and strokes – represents the leading cause of death in the United States [1]. High blood pressure (HBP) – also known as hypertension – is a key risk factor for heart disease. A systolic blood pressure of 130 mmHg or higher or a diastolic blood pressure of 80 mmHg or higher signifies HBP [2]. A third of U.S. adults – 75 million individuals – have HBP and this contributed to over 635,000 heart disease related deaths in 2016 [3]. Although HBP cannot be reversed, it can be controlled through lifestyle changes and medication. For example, a change in diet may reduce HBP as much as 11.4 mmHg (systolic) and 5.5 mmHg (diastolic) in patients with hypertension, within approximately 8 weeks [4]. Adherence to HBP medication has been shown to have an even larger effect. For example, a review of clinical trials illustrated that single drug therapy for loop diuretics (a class of HBP medications) may reduce HBP as much as 15.8 mmHg (systolic) and 8.2 mmHg (diastolic) in patients with hypertension, within a week’s time [5].

Although medication may have the most immediate impact on HBP, patients with hypertension often struggle with adhering to their medication regimens. Medication adherence has been broadly defined as taking medication as prescribed, and involves initiation of the treatment, taking the correct dose at the correct time, and taking the medication for as long as it is needed [6]. Nearly half of HBP medication regimens are not followed [7]. Previous studies describe numerous barriers that patients with HBP encounter to medication adherence, including: challenges that emerge in everyday life such as forgetting and physical challenges such as dealing with undesirable side effects, as well as psychological challenges such as depression, and financial challenges such as cost [8–11]. To address these medication adherence barriers, previous studies have identified approaches that support adherence, including: a consistent routine, support from family and friends, engagement with a pharmacy, and a trusting, positive relationship with a health care provider [12–16].

Medication adherence studies show differences in adherence to medication regimens between ethnic and racial groups. For example, data show that African Americans are less adherent to their HBP medication compared to white populations [17, 18]. These differences in medication adherence along with lifestyle factors, contribute to black-white disparities in blood pressure control, which result in differences in mortality risk for stroke; this risk is twice as great for African Americans, compared to Caucasians [19, 20].

There have been numerous intervention studies that have targeted HBP among African Americans and have shown promising results, including clinical care interventions, church-based self-management programs, community-based prescription programs in barbershops, and community-based physical activity programs [21–24]. However, many of these studies target one primary setting. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute recently convened a working group on research that is needed to improve hypertension treatment and control among African Americans [25]. One key finding from this working group was the need to test interventions that target multiple ecological levels from the individual level to the family level, to the policy environment. Specifically, the working group called for intervention research that tests three or more levels. Despite numerous studies on hypertension medication adherence, HBP control, and premature death, more investigation of medication adherence across multiple ecological settings is needed. This should be specific to African American populations and should explore their “lived experience.” Therefore, the purpose of this study is to examine barriers and facilitators of medication adherence for African Americans, across multiple ecological levels.

Method

Design and Context

We conducted in-depth key informant interviews and identified key themes from these interviews [26, 27]. More specifically, this involved: 1.) Developing and using a semi-structured interview guide to collect data, 2.) Extensive transcript review, 3.) Team-based generation of codes, 4.) Independent coding, 5.) Consensus building, 6.) The development of a diagram to connect themes, and 7.) Member checking.

The present study emerged from West Side Alive (WSA), a partnership between an academic medical center and a group of seven urban African American churches in Chicago. The churches are located on the predominantly African American west side of Chicago, which is a set of neighborhoods that face poverty, lower educational attainment, higher rates of violence and higher levels of chronic disease, compared to other (nearby) neighborhoods. The WSA partnership had recently conducted health screenings for over 1,000 individuals – both members of these churches and interested community residents – who were not have been members of any of the churches [28].

Participants and Data Collection

Participants had to meet the following five criteria for inclusion in this study: 1.) Be a member of one of the partner churches (or a participant in one of their health screenings), 2.) Identify as either African American or Black, 3.) Be 18 years or older, 4.) Be prescribed at least one medication for HBP, and 5.) Report not taking HBP medication as prescribed. We sampled study participants using aspects of convenience sampling. To do this, we provided the health screening participant list and study criteria to a coordinator in each of the seven churches (coordinators were church members who are paid to administer health programming) to schedule participants, using an initial (convenience) sampling approach. Both the church coordinators and the authors of the present study scheduled the individual interviews via phone, in consecutive batches of 2–4 participants, back-to-back. After each batch, interviews were transcribed, transcriptions reviewed, and initial coding conducted. All interviews were held in the churches, in a private room.

Instruments

We used three data collection instruments: An interview guide, a demographic questionnaire, and the Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ); the latter two instruments were used to describe the sample. University institutional review boards (at all authors’ institutions) reviewed and approved all study procedures. Participants provided written consent prior to the study and at the conclusion of the interview, we provided participants with a $20 cash incentive.

Interview guide.

The semi-structured interview guide consisted of eight main open-ended questions. The interviewer asked each question and probed for clarification to gather deeper information. The eight open-ended questions can be viewed in Table 1. We conducted interviews in a private room at each church. Interviews were recorded using a digital audio recorder and transcribed verbatim.

Table 1.

Open-Ended Questions on Interview Guide

| Question |

|---|

| 1. I’d like to begin by asking how HBP affects you. |

| 2. Now, think back to the most recent day you can remember, where you took your HBP medicine(s) as prescribed. Can you walk me through that day? |

| 3. Next, think back to the most recent day you can remember, where you DID NOT take your HBP medicine(s) as prescribed. Can you walk me through that day? |

| 4. When your HBP medication(s) run out, what are the steps you go through to refill it/them? |

| 5. Can you tell me about a time that someone in your life helped you take your HBP medication(s)? |

| 6. Can you tell me about a time that you visited your doctor and discussed your HBP? |

| 7. Can you tell me about the treatment plan your doctor provided for your HBP? |

| 8. Is there anything else that you would like to share about taking your HBP medication(s)? |

Demographic questionnaire.

Following the interview, participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire, consisting of closed-ended items, including: sex, educational level, employment status, date of birth, marital status, how long they had known of their HBP, difficulty paying bills, receipt of food stamp assistance, health status, number of HBP medications prescribed, and source of health insurance (if applicable).

Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ).

Participants completed ten items related to blood pressure medications from the BMQ. These items examine patient perceptions of necessity (5 items) and concerns (5 items) of prescribed medications [29]. Each item provides a short statement (e.g., “My health in the future will depend on my medicines”). Participants provide a rating from 5 (“Strongly Agree”) to 1 (“Strongly Disagree”). The sum of concern items are subtracted from the sum of necessity items for an aggregate score in which positive values suggest that the patient perceives the benefits of medication outweighs costs/concerns. Negative scores suggest that the costs/concerns outweigh the benefits. The BMQ developers validated the measure, demonstrating predictive validity.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data (from the demographic questionnaire and BMQ) was entered into Microsoft Excel for descriptive analysis. Qualitative data was analyzed through multiple phases: engagement with the data, code development, thematic coding among team members (including diagramming theme connectedness), review of themes, naming themes, and producing a report [27]. We used Dedoose (Version 8.2.14; SocioCultural Research Consultants, 2019) to analyze our data. Our analysis also involved code counts and participant counts (the count of participants that received the code one or more times). Qualitative scholars have noted several advantages to counting qualitative codes – specifically, recognizing patterns in qualitative data and representing the data holistically [30, 31]. To validate data, we had two authors independently code each interview. Then, coders discussed any disagreements until a consensus emerged. We conducted member checking with participants to establish trustworthiness of the data and assure credible findings [32]. Member checking involved a systematic review of each aspect of the themes and diagram of theme connectedness.

Findings

We conducted 21 interviews, at which point no new themes emerged related to barriers or facilitators of HBP medication adherence. We conducted an additional three interviews. No new themes emerged in these final three interviews; therefore, we ended data collection and our final dataset consisted of 24 participant interviews. On average, interviews took approximately 31 minutes.

Participant Characteristics

Table 2 provides demographic characteristics of the 24 participants in the study. Women represented the majority of participants (58.3%). Participant age averaged 59.5 years. A slight minority of participants were married (45.8%). Over 62% had at least some college, but 29.2% were unemployed and 62.5% were receiving government assistance.

Table 2.

Participant Demographic Characteristics (N=24)

| Demographic Attribute | Count | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Women | 14 | 58.3% |

| Men | 10 | 41.7% |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 9 | 37.5% |

| Married | 11 | 45.8% |

| Divorced | 2 | 8.3% |

| Widowed | 2 | 8.3% |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 1 | 4.2% |

| High school | 8 | 33.3% |

| Some college | 12 | 50.0% |

| College or advanced degree | 3 | 12.5% |

| Employment | ||

| Full time | 6 | 25.0% |

| Part time | 3 | 12.5% |

| Unemployed | 7 | 29.2% |

| Retired | 8 | 33.3% |

| Receiving Food Assistance (e.g., SNAP) | ||

| Yes | 15 | 62.5% |

| No | 9 | 37.5% |

| BP Medications Prescribed | ||

| 1 to 2 medications | 19 | 79.2% |

| 3 to 4 medications | 5 | 20.8% |

| Know of High HBP | ||

| 1 to 3 years | 4 | 16.7% |

| 4 to 6 years | 3 | 12.5% |

| 7 years or more | 17 | 70.8% |

| Beliefs About Medicines Questionnaire | ||

| Benefits Outweigh Costs & Concerns | 17 | 70.8% |

| Costs & Concerns Outweigh the Benefits | 5 | 20.8% |

| Neither (Score = 0) | 1 | 4.2% |

| Missing | 1 | 4.2% |

| Health Insurance (Multiple Selections) | ||

| State Medical Card, Medicaid, County Care | 13 | 54.2% |

| Medicare | 8 | 33.3% |

| Insurance through a current or former employer or union | 2 | 8.3% |

| TRICARE or other military health care | 1 | 4.2% |

| Veterans’ benefits | 1 | 4.2% |

| No health insurance or medical card* | 1 | 4.2% |

| General Health | ||

| Excellent | 2 | 8.3% |

| Very Good | 8 | 33.3% |

| Good | 7 | 29.2% |

| Fair | 6 | 25.0% |

| Poor | 1 | 4.2% |

Note: Although Participant 1 indicated having health insurance, she described a recent lapse in her coverage during the interview, bringing the “No health insurance” count to 2.

Nearly eighty percent of participants (79.2%) were prescribed 1 to 2 HBP medications and over 83% of participants had known of their HBP for 4 years or longer. BMQ data showed that 70.8% of participants felt that the benefits of their HBP medication outweighed the costs and their concerns of their medication. Only 4.2% of participants lacked health insurance, and despite having HBP, over seventy percent of participants ranked their health as “Good” to “Excellent.”

Emergent Themes

Our final codebook consisted of 22 codes that described barriers to medication adherence and 32 codes that described facilitators to medication adherence. Table 3 provides each barrier code, a short definition and a code count and participant count (i.e., count of participants that received the code one or more times). Participants reported undesirable side effects as the most frequent barrier to medication adherence (20 occurrences). An interruption in routine represented the second most frequent barrier (19 occurrences), followed by general forgetting (18 occurrences).

Table 3.

Barrier Codes (N=22) that Emerged During Interviews (Sorted in Descending Order by Code Count)

| Code | Short Definition | Code Count |

Participant Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Undesirable Side Effect | Not taking medication because of side effect(s) | 20 | 10 |

| 2. Routine Interrupted | Not taking medication because of a change in routine | 19 | 13 |

| 3. General Forgetting | Forgetting to take medication | 18 | 9 |

| 4. Forget So Delay | Forgot to take medication, so delaying it until next dose | 13 | 9 |

| 5. Lack Motivation | Lack motivation for taking or refilling medication | 11 | 6 |

| 6. Cost Challenging | Not refilling medication due to cost or lack of insurance | 10 | 5 |

| 7. Fatigue Pain Illness | Not taking medication because of fatigue, pain, illness | 6 | 3 |

| 8. Attitude Mistrust Drugs | Uncomfortable putting drugs/chemicals into body | 4 | 2 |

| 9. Misplacement | Not taking medication because it is in an inconvenient place | 4 | 4 |

| 10. Getting Medical Procedure | Not taking medication because of medical procedure | 3 | 2 |

| 11. Attitude Good Numbers | Lack motivation when feeling fine or HBP numbers are good | 3 | 3 |

| 12. Mistrust Medical System | Not taking medication because of mistrust in medical system | 3 | 1 |

| 13. Lack Knowledge Importance | Not taking medication because of not knowing the importance | 2 | 1 |

| 14. Mood Stress Depression | Not taking medication because of mood, stress, or depression | 2 | 2 |

| 15. Other Causes Forgetting | Not taking medication because someone caused them to forget | 2 | 2 |

| 16. Lack Routine | Not taking medication because lacking daily routine | 2 | 1 |

| 17. Mail Error | Issue with mail prevents participant from taking medication | 2 | 2 |

| 18. Attitude Lack Motivation Change Med | Lack motivation for talking to doctor to change medication | 1 | 1 |

| 19. Keep Medication Children | Keeping medication away from children results in nonadherence | 1 | 1 |

| 20. Transportation Barrier | Not refilling medication due to lack of transportation | 1 | 1 |

| 21. Logistics For Price | Burdened by visiting multiple pharmacies for best price | 1 | 1 |

| 22. Supplier Recall | Medication recalled by drug manufacturer | 1 | 1 |

Note: HBP = High Blood Pressure

Participants reported personal reminders to take medication as the most frequent facilitator of medication adherence (26 occurrences). Motivation to address or prevent a symptom represented the second most frequent facilitator (15 occurrences), followed by having a general resolve to take medication (13 occurrences). Table 4 provides each facilitator code.

Table 4.

Facilitator Codes (N=32) that Emerged During Interviews (Sorted in Descending Order by Code Count)

| Code | Short Definition | Code Count |

Participant Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Personal Reminder | Receiving a reminder to take medication | 26 | 16 |

| 2. Symptom Motivation | Taking medication to address or prevent a symptom | 15 | 9 |

| 3. Resolve Take Med | Participant has resolve to take medication | 13 | 8 |

| 4. Placement Strategy | Putting medication in a consistent place | 13 | 9 |

| 5. Routine | Having a daily routine to take medication | 12 | 9 |

| 6. Instrumental Support | Getting help with a specific task related to taking HBP medication | 8 | 7 |

| 7. General Doctor Prompt | Receiving a prompt from a doctor to take medication | 7 | 3 |

| 8. Pharmacy System | Pharmacy system prompts participant to get refill | 6 | 6 |

| 9. On Mind | Having medication “on mind” | 5 | 3 |

| 10. Insurance Assures Affordability | Having insurance makes HBP medication affordable | 3 | 3 |

| 11. Sharing Medication | Participant receives medication from personal contact | 3 | 3 |

| 12. Talked To Others | Taking HBP medication when motivated by a conversation | 3 | 2 |

| 13. Doctor Educates Medication | Doctor educates participant about HBP medication | 3 | 3 |

| 14. Organizing Meds | Participant organizes medication to ensure adherence | 3 | 2 |

| 15. Positive Feelings Meds | Participant has positive feeling about medication | 2 | 2 |

| 16. Refill Flexibility | Participant describes having multiple refill options | 2 | 1 |

| 17. Alternative Pharmacy Program | Participant gets doctor recommendation for refill program | 2 | 2 |

| 18. Away From Home | Being away from home makes medication adherence easier | 1 | 1 |

| 19. Early Bedtime | Going to bed early makes medication adherence easier | 1 | 1 |

| 20. Placement Edibles | Putting water or food near medication | 1 | 1 |

| 21. Take Meds Together | Taking multiple pills at one time | 1 | 1 |

| 22. Insurance Incentives | Purchasing non-medicine items w/medical card motivates refills | 1 | 1 |

| 23. Obtain Money Prescription | Borrowing money from others to obtain HBP medication | 1 | 1 |

| 24. Live By Pharmacy | Living near a pharmacy makes picking up medication easy | 1 | 1 |

| 25. Taking Med With Other | Taking medication at the same time as someone else | 1 | 1 |

| 26. Street Contact | Participant gets HBP medication from contact “on the street” | 1 | 1 |

| 27. Pharmacist Prevents Problems | Pharmacy contacts doctor to prevent patient medication issue | 1 | 1 |

| 28. Doctor Further Diagnosis | Doctor recommends additional tests for ideal HBP medication | 1 | 1 |

| 29. Doctor Offers Solution | Doctor helps participant troubleshoot adherence barrier(s) | 1 | 1 |

| 30. Medical Appointment Stalled | Taking medication to avoid delay during medical appointment | 1 | 1 |

| 31. Experimentation | “Experimenting” with medication regime motivates adherence | 1 | 1 |

| 32. Flexible Medication Schedule | Flexibility in time of day to take medication motivates adherence | 1 | 1 |

Note: HBP = High Blood Pressure

Theme Development, Validation, and Description

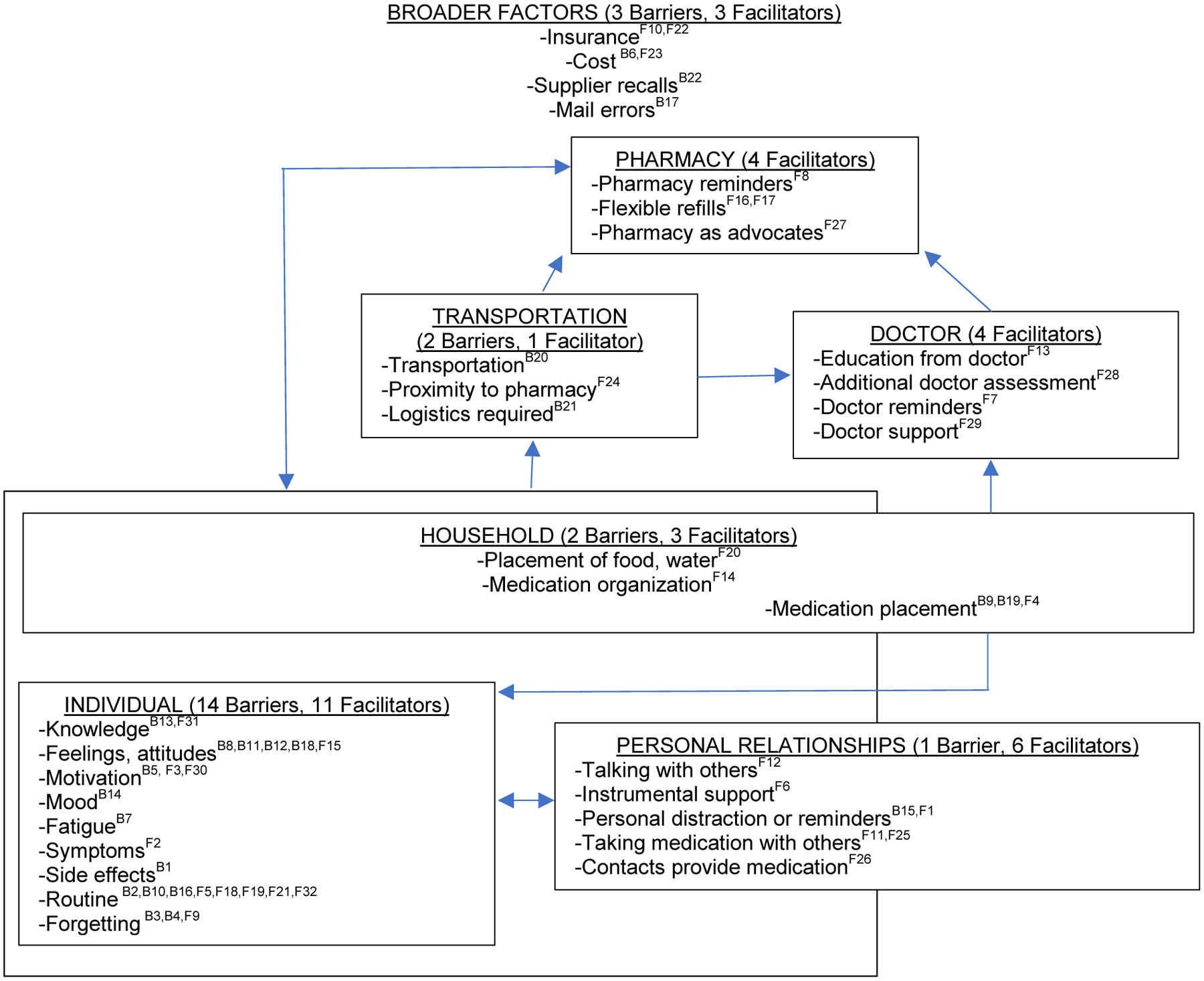

Throughout the data collection process, we developed a visual representation of the themes (Figure 1). Participants experienced the barriers and facilitators of medication adherence across several distinct ecological levels and settings, including the individual, household, relationship, and broader societal levels. Barriers and facilitators also influenced medication adherence across several settings, including the doctor’s office, pharmacy, and transportation (to the doctor’s office and the pharmacy).

Fig. 1.

This diagram depicts the barriers and facilitators that affect medication adherence, across multiple levels and settings. Superscripts indicate barriers (B) and facilitators (F) by code number (from Tables 3 and 4)

We conducted two member-checking discussions with four participants (2 women and 2 men) to establish “trustworthiness” of the data and assure credible findings [32]. The discussion facilitator provided participants with the diagram of theme connectedness (Figure 1) and walked participants through each ecological level, setting, and related code category, posing the question, “When you think about taking blood pressure medication, is there anything that we have misunderstood?” Participants did not identify any misunderstandings with ecological levels, settings, or code categories. Qualitative results are provided across each ecological level and setting as depicted in Figure 1.

Individual.

On the individual level, 14 barriers and 10 facilitators to HBP medication adherence emerged. Nine participants believed that taking their medication was a way to avoid or reduce the perceived physical effects of hypertension – the most commonly reported being headaches. For example, one participant said, “I woke up with a headache and then later on in the day the headache was still not disappearing… so I took a blood pressure pill which eventually alleviate[d] the headache.” Other participants believed that taking their medication resulted in physical side effects – including headaches. Another participant remarked, “Oh my God. That stuff [hypertension medication] was so horrible…it gave me the most intense headache I ever had.”

Participants also reported several psychological factors that affected adherence. Motivation represented one such factor. A participant described feeling a lack of motivation for taking her medication, despite seeing the effects of chronic disease in her family, “…blood pressure is important, I’m still trying to, you know, get myself to the point where, ‘[I say] hey take this seriously’.” However, for another participant, seeing his brother in the hospital created resolve for taking his medication, “My brother – he had a quadruple bypass surgery. He’s only like four years older than me. Yeah. Oh no man, I ain’t, I didn’t want to be laid up in the hospital. I don’t want to be takin’ on [additional] medication…it’s just like this, you know?”

A few participants held attitudes of mistrust with medications – one described his mistrust with medication production, “Because now, everything’s made overseas, mostly. In different countries…but, I read everything and am concerned about that…A small country that doesn’t have a law. They’ll say, well this, the basic thing that makes me feel like this [is that the] government has stopped, you know having rules, here.” Another participant described an attitude of mistrust related to potential long-term side effects of HBP medication, “I’m not a believer in medication per se. I’m just not one. I just believe that eventually pills have long term side effects on you, so if I can alleviate without taking them and I don’t have to, I won’t.

Finally, behavioral factors presented barriers and facilitators to medication adherence, on the individual level. Nine participants reported general forgetting as a barrier to medication adherence (e.g., One of these participants said, “And then there have been times that I have forgotten to take the medicine out of just forgetfulness, you know just forgot to take it.”). However, nine of the participants said they rely on a routine as a primary way to assure adherence. For example, one participant said, “It’s just a daily routine once I brush my teeth and all that good stuff and take my bath, I just go straight to the medicine cabinet take my vitamins and medications that I have to take.” Routine was effective for one participant when away from home, for another when going to bed early, and for a third when her doctor allowed her to switch the daily time that she took her HBP medication.

Household.

Within the household, participants described their placement of medication as a key facilitator to ensuring they took it as prescribed. Participants described keeping their medication at their bedside, and this being a cue for them to take it. For example, a participant said, “Its right there. It’s in your bed in the bedside table so you remember to take [it].” The most frequent household barrier was misplacement of medication – “I didn’t put it on the table, and I forgot.” In some cases, misplacement was intentional, but it affected adherence, “I don’t want it on my nightstand in my bedroom, because my nightstand is not that tall, and I have grandbabies [who might get into the medication].” Although the focus of misplacement was within the house, participants also described misplacement of medication when traveling and when out of the house (e.g., “I keep my medication in my purse when I am traveling…most of the time the bag is left in the car.”)

Personal relationships.

Personal reminders were the most frequent facilitator to take medication – 16 of 24 participants described a personal reminder as a facilitator to medication adherence. This type of reminder came from a variety of people: mothers, siblings, spouses/partners, and children. One participant described personal reminders coming from multiple family members, “So my family are consistently on me about taking my blood pressure medicine, consistently talking about, you know, how it is important, the effects of not taking it. So yes, I do have a great support system with those around me, coworkers, family, you know, so on.”

In addition to reminders and personal support, participants talked about sharing medication. This could involve receiving medication from a personal contact (“It may have been like two days or something [time in which she was out of medication], but you just try to take something, and you may find out some more people are on the same medicine you are, and they may give you a pill.” Another participant – who lacked health insurance – described turning to contacts on the street to obtain medication (but having to pay for it), “I have a couple, on the street…you pay for it. And you have to make sure it is real cause there are medicines for different things…you Google it.”

Doctor and pharmacy.

Only facilitators emerged when participants described their experience with their doctor (4 facilitators) and their pharmacy (4 facilitators). Participants describe their doctor prompting them to take their HBP medication; this often involved simple verbal statements during appointments. For example, one participant remarked, “[The doctor] always say[s] this line ‘I can’t make you take it because I’m not with you all the time. So, you need to work on taking your medication’.” Participants also described doctors educating them on their medication during appointments (“She [doctor] asks me what I want to know… she tells me why I am taking them.”). Another participant described her doctor problem-solving the “nauseous” feelings she felt in the morning after taking her medication, “So he [the doctor] was like well why don’t you stop taking it in the morning and just try it in the evening and see how that works and I’m like okay I’m going to try it in the evening.”

Overall, participants expressed satisfaction with their pharmacies. Participants described pharmacies’ use of text messaging and automated phone calls as a facilitator to medication adherence, “I don’t even have to call [the pharmacy]. Now they send a text to my phone. If I don’t respond to the text, then they’ll call me.” A participant described her relationship with the pharmacist as strong and described having a new prescription filled. The pharmacist reviewed the new prescription and said, “Well you know with this prescription here, it’s going to have some side effect with this medication so before you take it let me call and make sure they want you to take this because you are on this medicine so give me five minutes to not go nowhere,” in which the participant recalled responding to this by saying, “okay please make sure you get me better.”

Transportation.

Only three codes emerged, related to transportation (across 3 participants, total). Two participants commented on proximity to the pharmacy. One participant had easy access to the pharmacy, stating, “It’s right down the street from my house…I walk.” Another participant faced the opposite situation, “Sometimes my bus card do run out or I can’t use the bus card – my sister has it…so other than that, that is the only thing that stops me from getting to where I need to get to, so maybe once or twice a week [I] might have bus fare problems.” A third participant had lost her insurance coverage and used an online resource to identify where she could find the most cost-efficient medication (she had several chronic conditions including hypertension and diabetes). Her situation resulted in challenges to logistics, “If I’m getting it at this price at this place I should be able to go to this place with, with the fluctuation they got me going I got four different pharmacies to get my medication.”

Broader factors.

Broader factors that affect obtaining medication emerged across the interviews – including cost, insurance, mail errors, and supplier recalls. Among the 5 participants that cited cost as a challenge to medication adherence, 2 participants lacked health insurance. Costs associated with health services affected one participant, as she exclaimed, “You can’t go to the pharmacy – [at the] pharmacy you need a prescription and for a prescription you need money for the doctor.” Another participant maintained access to health care (despite a lapse in insurance coverage due to a mail error) but having to pay for multiple medications made the cost challenging, “But I did not have a prescription plan, blood pressure medicine is not that expensive, but I have other medications that are, so, you know.” Participants who had insurance found that their coverage paid all (or nearly all) the cost of the medication. Beyond insurance issues and costs, one participant cited “I had stopped taking one particular medication. The one that they had a recall on [it].”

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the facilitators and barriers to medication adherence among African Americans with HBP and develop a comprehensive representation of theme connectedness. This type of diagram is important to guide effective interventions that span multiple ecological levels, as previously called for [25]. The codes that emerged from the data show several social determinants of health – including transportation, technology (i.e., refill reminders via text message), and social support (i.e., instrumental support) – facilitate adherence [33].

It is important to consider the participant sample in the present study, when interpreting the representativeness of the themes in the diagram of theme connectedness. Demographic data reveal a slight overrepresentation of women (58.3%) and only one participant (4.2%) reported not having health insurance, which is lower than a recent, national estimate of uninsured individuals in the United States at 8.8% [34]. Qualitative research strives for transferability rather than generalizability, and the diagram of theme connectedness developed in this article would be most transferable to insured African American populations [32]. Data from the BMQ showed that over 70% of participants felt that the benefits of their HBP medication outweighed the costs and their concerns for the medication. Further, over 70% of the sample rated their health as “Good” to “Excellent” despite having HBP. This more positive view of medication and health may have been due to the length of time that participants knew of their hypertension status– over 83% of the sample knew of their hypertension for four years or more. Patients who have not known of their hypertensive status for this length of time may not be as likely to hold positive beliefs about their medication or strategies for adherence and may face barriers that did not emerge in this study. The study criteria present another consideration for these findings. Patients were required to be taking at least one HBP medication. Our demographic data show that slightly more than 79% of participants indicated taking 1 to 2 medications. Those taking just 1 to 2 medications may not experience the same number of barriers to medication adherence, compared to patients taking more than two HBP medications. Future studies may examine barriers and facilitators to medication adherence among patients taking 3 or more medications.

It was surprising that more facilitators to medication adherence emerged (N=32) than barriers to medication adherence (N=22). If we disregard barriers and facilitators that had a participant count of one (i.e., only one participant in our sample reported this barrier or facilitator), we would be left with 17 barriers and 17 facilitators. This suggests that among our sample, the facilitator list may have been longer than the barrier list because of some unique facilitators that only one participant reported. Future research may examine the prevalence of HBP medication adherence strategies.

The largest number of barriers and facilitators emerged on the individual level. This suggests that hypertension medication adherence interventions should focus on individual level barriers (e.g., strategies to adhere to medication during periods of depression or physical pain). Further, the effects of seeing family members hospitalized (or die) from HBP-related health events such as heart attacks and strokes seemed to create resolve for one patient to take his HBP medication regularly, while it seemed to have little effect on another participant who witnessed multiple family members die of strokes. This suggests that multi-level interventions need to allow for personal tailoring on the individual level, based on perceptions and motivations.

In this study, participants’ experience with health systems – doctors and pharmacies – was unanimously positive, consisting of only facilitator codes. The presence of only facilitators and no barriers among doctors and pharmacists (and majority facilitators among transportation) suggest that these aspects of adherence – filling prescriptions and attending appointments – are likely not an issue. This finding was also encouraging as previous studies report a sense of mistrust between African Americans with HBP and their physician [35–37]. It is possible, however, that individuals who agreed to participate in the present study had better relationships with their health care providers than the broader African American population. The results of the present study confirms that there is a key role for both health care providers and personal contacts, to play in promoting medication adherence.

There are numerous studies that have examined medication adherence among African Americans with hypertension [38, 12, 11]. The present study expands on this work by providing a diagram of barriers and facilitators to medication adherence, across the social ecology, that emerges from the lived experience of the participants. It is important to note that despite the use of in-depth thematic analysis, certain factors from the HBM adherence literature did not emerge in this study. For example, several studies have identified self-efficacy as a key factor to medication adherence [39, 9]. Self-efficacy did not emerge as a theme in our study and this may have also been due to the fact that participants have known of their HBP status for some time and are less attentive to their general sense of efficacy.

This study had several strengths. These key informant interviews allowed for an in-depth exploration of medication adherence among a sample of individuals that face high levels of chronic disease. This study took a qualitative, thematic approach, and enabled the construction of a multi-setting diagram of theme connectedness of barriers and facilitators to medication adherence. Finally, data was validated through independent coding and member checking. Despite these strengths, the study faced several limitations. One limitation of the study was the use of convenience sampling which may have implications for transferability of findings to other settings. Our findings would be most transferable to urban, African Americans that attend church. Our sample reflected an older patient population, that had known of their hypertensive status for several years. Future research may involve a more purposeful sampling strategy to target participants who have specific blood pressure readings and may be newer to managing medications and hypertension.

Participants in this study faced barriers to taking their HBP medication, but developed numerous facilitators to adhere to their medication regimens. This study enabled the development of a diagram of theme connectedness for HBP medication adherence that emerged from participants’ “lived experience.” This diagram aligns and expands upon previous literature that examines specific barriers and facilitators to medication adherence. This diagram can be used to guide interventions that promote medication adherence among African Americans, that span multiple settings and ecological levels, and address disparities that African Americans face in medication adherence, HBP control and ultimately, mortality.

Funding:

This project was funded by the Irwin W. Steans Center’s Community-based Research Faculty Fellowship.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article. Dr. Ruppar has served as a consultant for Becton Dickinson.

References

- 1.Heron M Deaths: Leading causes for 2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67(6):1–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr., Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C et al. Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2018; 10.1161/cir.0000000000000596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. High blood pressure. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/index.htm. Accessed 29 Apr 2020.

- 4.Roberts CK, Barnard RJ. Effects of exercise and diet on chronic disease. J Appl Physiol. 1985; 10.1152/japplphysiol.00852.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu J, Kraja AT, Oberman A, Lewis CE, Ellison RC, Arnett DK et al. A summary of the effects of antihypertensive medications on measured blood pressure. Am J Hypertens. 2005; 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vrijens B, De Geest S, Hughes DA, Przemyslaw K, Demonceau J, Ruppar T et al. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012; 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04167.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005; 10.1056/NEJMra050100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim MT, Han HR, Hill MN, Rose L, Roary M. Depression, substance use, adherence behaviors, and blood pressure in urban hypertensive black men. Ann Behav Med. 2003; 10.1207/s15324796abm2601_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoenthaler A, Ogedegbe G, Allegrante JP. Self-efficacy mediates the relationship between depressive symptoms and medication adherence among hypertensive African Americans. Health Educ Behav. 2009; 10.1177/1090198107309459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viswanathan H, Lambert BL. An inquiry into medication meanings, illness, medication use, and the transformative potential of chronic illness among African Americans with hypertension. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2005; 10.1016/j.sapharm.2004.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young JH, Ng D, Ibe C, Weeks K, Brotman DJ, Dy SM et al. Access to care, treatment ambivalence, medication nonadherence, and long-term mortality among severely hypertensive African Americans: A prospective cohort study. J Clin Hypertens. 2015; 10.1111/jch.12562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solomon A, Schoenthaler A, Seixas A, Ogedegbe G, Jean-Louis G, Lai D. Medication routines and adherence among hypertensive African Americans. J Clin Hypertens. 2015; 10.1111/jch.12566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flynn SJ, Ameling JM, Hill-Briggs F, Wolff JL, Bone LR, Levine DM et al. Facilitators and barriers to hypertension self-management in urban African Americans: Perspectives of patients and family members. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013; 10.2147/ppa.S46517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferdinand KC, Yadav K, Nasser SA, Clayton-Jeter HD, Lewin J, Cryer DR et al. Disparities in hypertension and cardiovascular disease in blacks: The critical role of medication adherence. J Clin Hypertens. 2017; 10.1111/jch.13089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Go AS, Bauman MA, Coleman King SM, Fonarow GC, Lawrence W, Williams KA et al. An effective approach to high blood pressure control: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abel WM, Efird JT. The association between trust in health care providers and medication adherence among black women with hypertension. Front Public Health. 2013; 10.3389/fpubh.2013.00066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Racial/ethnic disparities in the awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension - United States, 2003–2010. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(18):351–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoon SS, Carroll MD, Fryar CD. Hypertension prevalence and control among adults: United States, 2011–2014. 2015;220:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Boscardin WJ, Ettner SL. Contribution of major diseases to disparities in mortality. N Engl J Med. 2002; 10.1056/NEJMsa012979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lackland DT. Racial differences in hypertension: Implications for high blood pressure management. Am J Med Sci. 2014; 10.1097/maj.0000000000000308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong JC, Padula WV, Hollin IL, Hussain T, Dietz KB, Halbert JP et al. Care management to reduce disparities and control hypertension in primary care: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Med Care. 2018; 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White HL. Promoting self-management of hypertension in the African-American church. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 2018;29(1):6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Victor RG, Lynch K, Li N, Blyler C, Muhammad E, Handler J et al. A cluster-randomized trial of blood-pressure reduction in black barbershops. N Engl J Med. 2018; 10.1056/NEJMoa1717250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kling HE, D’Agostino EM, Booth JV, Patel H, Hansen E, Mathew MS et al. The effect of a park-based physical activity program on cardiovascular, strength, and mobility outcomes among a sample of racially/ethnically diverse adults aged 55 or older. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018; 10.5888/pcd15.180326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whelton PK, Einhorn PT, Muntner P, Appel LJ, Cushman WC, Diez Roux AV et al. Research needs to improve hypertension treatment and control in African Americans. Hypertension. 2016; 10.1161/hypertensionaha.116.07905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braun V, Clark V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006; 3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lynch EB, Williams J, Avery E, Crane MM, Lange-Maia B, Tangney C et al. Partnering with churches to conduct a wide-scale health screening of an urban, segregated community. J Community Health. 2019; 10.1007/s10900-019-00715-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999; 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00057-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maxwell JA. Using numbers in qualitative research. Qual Inq. 2010;16(6):475–82. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandelowski M, Voils CI, Knafl G. On quantitizing. J Mix Methods Res. 2009;3(3):208–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tolley EE, Ulin PR, Mack N, Robinson ET, Succop SM Qualitative methods in public health: A field guide for applied research. San Francisco: Wiley; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Services USDoHH. Social determinants of health. 2020. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health. Accessed 29 Apr 2020.

- 34.Berchick ER, Hood E, Barnett JC. Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2017. United States Census Bureau. 2018. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2018/demo/p60-264.pdf. Accessed 29 Apr 2020.

- 35.Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, LaVeist TA, Powe NR. Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Rep. 2003; 10.1093/phr/118.4.358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hammond WP. Psychosocial correlates of medical mistrust among African American men. Am J Community Psychol. 2010; 10.1007/s10464-009-9280-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.LaVeist TA, Nickerson KJ, Bowie JV. Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among African American and white cardiac patients. Med Care Res Rev. 2000; 10.1177/1077558700057001s07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hekler EB, Lambert J, Leventhal E, Leventhal H, Jahn E, Contrada RJ. Commonsense illness beliefs, adherence behaviors, and hypertension control among African Americans. J Behav Med. 2008; 10.1007/s10865-008-9165-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lewis LM. Factors associated with medication adherence in hypertensive blacks: A review of the literature. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2012; 10.1097/JCN.0b013e318215bb8f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]