In this issue of AJPH, Bender and Lauritsen (p. 318) use the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) since it began including sexual orientation and gender identity data in 2017 to detail sobering findings about violence endured by sexual minorities in the United States. For example, compared with heterosexual women, gay and bisexual men and lesbian and bisexual women all had greater odds—ranging from 90% to 261% increased odds—of reporting violent victimization in the last six months, including serious crimes like sexual and physical assault. Such a clear, nationally representative picture of how the wicked problem of violence disproportionately burdens sexual minority communities has, heretofore, been largely elusive, although the study results are not entirely surprising.

WHERE WE HAVE BEEN

For many health equity researchers, community advocates, and policymakers concerned about the health and well-being of sexual minority individuals, the findings are both a long-sought stanza and an expected chorus in a recitation of violence. The findings are long sought because, as the authors note, sexual orientation measures on federal surveys are not standard elements, and for many federal surveys, including NCVS, they are only recent additions. That sexual minorities can only now quantify victimization from the NCVS hearkens Sell and Holliday’s indictment of public health malpractice1; sexual minorities are a segment of the populace that funds federal surveys yet do not benefit from representation in said surveys. The results were expected because researchers for several decades have documented high rates of violent victimization among sexual minorities. In 1980, Miller and Humphreys2(p182) lamented in their article about gay men’s victimization that, “In lieu of a major study that will permit representative sampling . . . we are thrown back on availability samples and limited data.” The ensuing work over the next four decades relied on mostly convenience-based sampling,3 and the warnings of disparities were perhaps drowned out by louder warnings about biased sampling and limited generalizability. The siren now rings clear.

The ways that public health meets the challenge of addressing these disparities in violent victimization, however, are less clear. Of course, there has been social progress for sexual minorities. In the last decade, the United States saw the end of the US Department of Defense policy of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” that barred sexual minorities from openly serving in the military (although a separate ban on transgender persons is currently in effect), the legal recognition of same-sex marriage, and the protection from employment discrimination. Yet the NCVS data clearly show the seemingly ever unfinished business of equity in America. Sexual minority respondents to the NCVS who indicated surviving serious violent crime did so in the six months prior to the survey—in this era of increasing equality.

AREAS WE MUST FORGE

Mobilizing to conquer these disparities requires a deeper reckoning about the insidious architecture of violence against sexual minorities in the United States: the cunning ways that sexual minorities are made lesser and “other,” the entitlement of the perpetrators and the cultural and sociopolitical structures that embolden them, and the data and service systems inadequately designed for the hard work of equity.

The “othering” of sexual minorities happens overtly, and it quintessentially facilitates dehumanization that allows violence from an entitled majority. Sexual minorities can legally be refused housing in 23 states, and 11 states permit refusal of child welfare services to same-sex couples and their children.4 Devaluation also happens covertly when discrimination is wrapped in the facade of religious freedom, and denial of service is dismissed as a reality of capitalism. The mere act of deciding whether sexual minorities should have the right to marry or serve in the military—opportunities taken for granted by the majority but debated for a minority—is pageantry of oppression initiated by the question, “Is the minority worthy?” Arbitration of personhood is an effective dog whistle. Operationalizing these codified injustices and colloquial aggressions is an unfolding science mostly focused on sexual minorities, themselves, to understand the implications on their health. However, the lenses of science and prevention must expand to understand whether and how legislated discrimination may drive perpetration of violence and, if so, hold the blowers of the dog whistles accountable.

Perpetrators of violence against sexual minorities are largely unstudied in violence prevention. Violence prevention in the United States has uncanny penchants for recentering the responsibility on victims. For example, sexual assault prevention for women usually includes strategies about how strategically a woman should drink alcohol, how closely she should watch for date rape drugs, how she should dress, and how cautiously she should walk at night. Where are the widespread sexual assault prevention strategies that confront the irrational masculinity fueling men to think they are entitled to women’s bodies? In terms of sexual minorities, where are the prevention strategies that confront homophobic and heterosexist hegemonies casting sexual minorities as targets? At best, perpetrators’ actions are bemoaned as unpredictable, and at worst, they are viewed as justified; such dismissals sanction violence. Resources should be invested in understanding mutable characteristics of perpetrators to inform violence prevention. Simultaneous investments are necessary for public health researchers, social workers, and policymakers to develop community-based strategies to dismantle contextual factors that embolden perpetrators.

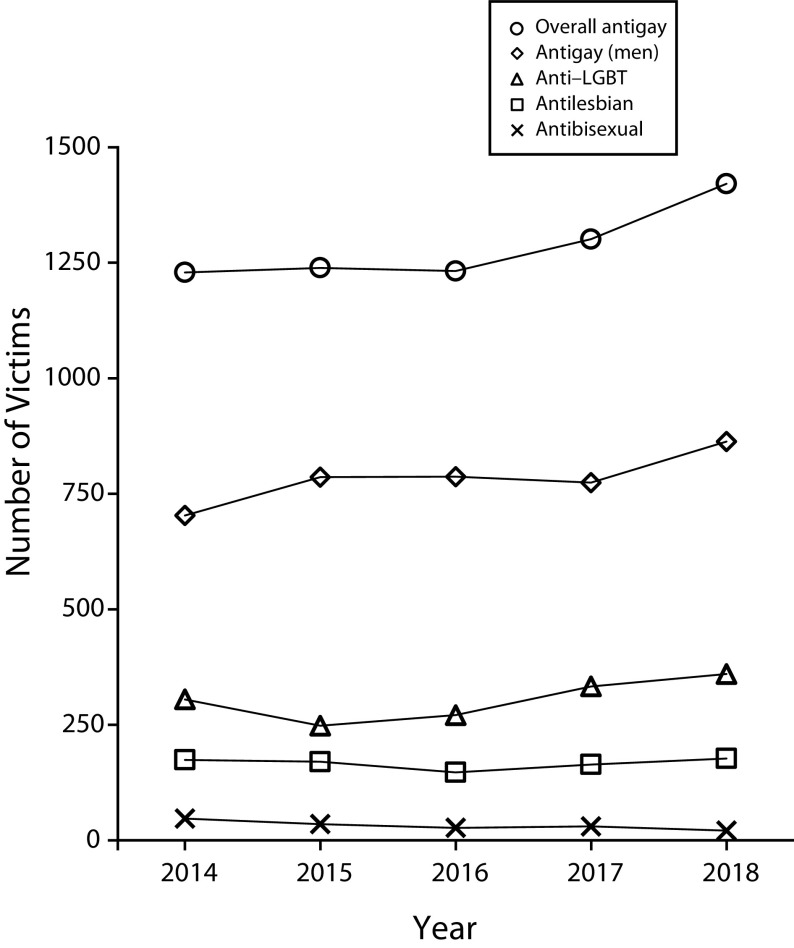

Finally, data systems and public services must meet the challenges of violence prevention and when prevention fails, honestly account the tolls of violence and serve the survivors. For example, the Federal Bureau of Investigation tracks hate crimes based on sexual orientation, indicating recent increases in sexual orientation–related hate crimes, particularly after 2016 (Figure 1).5 Yet the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s data system for hate crimes is voluntary and thus largely underestimates violence against sexual minorities. Although the NCVS data are a step toward finally achieving nationally representative estimates of violent crime victimization of sexual minorities, they alone are not enough. If sexual minorities are more likely to be victims of serious violent crime than are heterosexual persons, then a reasonable hypothesis is that death by violence is also more prevalent. Yet mortality data inclusive of sexual orientation barely exist. The NCVS results add a new layer of urgency to determine whether there are corresponding sexual orientation–related disparities in preventable deaths, which requires inclusion of data about sexual orientation in US mortality surveillance systems.6

FIGURE 1—

Number of Victims of Sexual Orientation–Based Hate Crimes, Federal Bureau of Investigation Uniform Crime Reporting: United States, 2014–2018

Note. LGBT = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender.

The NCVS results also challenge researchers, advocates, and policymakers to understand what happens when sexual minorities who are victimized then interface with legal and judicial systems; that is, if they decide to report their victimization. Limited research suggests that sexual minorities interpret police as biased,7 which could jeopardize reporting victimization, especially if that victimization was related to the victim’s sexual orientation. Even for crimes unrelated to the victim’s sexual orientation, disclosure of minority sexual orientation may emerge in official reporting or statements from spouses or partners, forcing disclosure. Again, Miller and Humphreys’ research about victimization among gay men observed that, “In being attacked, they [gay men] did not so much come out of the closet as have the closet involuntarily ripped from around them.”2(p178) The availability, acceptability, and preparedness of the postvictimization legal and social services fields for sexual minorities are vastly understudied in terms of their effectiveness for justice and healing.

Bender and Lauritsen provide America both with its clearest picture yet about violence suffered by sexual minorities and with a clarion call for public health research and practice, social work, law, and public policy to unite with communities for systemic efforts to reduce sexual orientation–related disparities in violence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (research award R21MH122852).

Note. The opinions expressed in this work are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the institution, funder, or US government.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

See also Bender and Lauritsen, p. 318.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sell RL, Holliday ML. Sexual orientation data collection policy in the United States: public health malpractice. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6):967–969. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller B, Humphreys L. Lifestyles and violence: homosexual victims of assault and murder. Qual Sociol. 1980;3(3):169–185. doi: 10.1007/BF00987134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rothman EF, Exner D, Baughman AL. The prevalence of sexual assault against people who identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual in the United States: a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2011;12(2):55–66. doi: 10.1177/1524838010390707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Movement Advancement Project. Snapshot: LGBTQ equality by state. October 28, 2020. Available at: https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps. Accessed November 4, 2020.

- 5.Federal Bureau of Investigation. FBI: UCR hate crime. Available at: https://ucr.fbi.gov/hate-crime. Accessed November 18, 2020.

- 6.Haas AP, Lane AD, Blosnich JR, Butcher BA, Mortali MG. Collecting sexual orientation and gender identity information at death. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(2):255–259. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Owen SS, Burke TW, Few-Demo AL, Natwick J. Perceptions of the police by LGBT communities. Am J Crim Justice. 2018;43(3):668–693. doi: 10.1007/s12103-017-9420-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]