Abstract

Amniotic membrane (AM) transplantation, when performed in the acute phase in Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) for patients with ocular complications, is known to reduce the morbidity of ocular complications in the chronic phase. In conditions such as SJS/TEN, AM needs to be secured to the ocular surface as well as the eyelids. Previously, techniques of securing a large sheet of AM with fibrin glue to the ocular surface and with sutures and bolsters to the eyelids have been described in the acute phase of SJS/TEN. These techniques often necessitate the use of an operating room in acutely ill patients. We describe a bedside technique that uses cyanoacrylate glue to secure the AM to the eyelids, as well as long-term outcomes in 4 patients with acute SJS/TEN. The combination of a custom symblepharon ring to secure AM over the entire ocular surface and cyanoacrylate glue to secure AM to the eyelid margins is quick, painless, does not require local or general anesthesia, and might prove useful in other conditions previously shown to benefit from AMT, such as ocular chemical injuries.

Keywords: amniotic membrane, ocular surface, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, cyanoacrylate glue

Introduction

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/ TEN) is a rare, immune-mediated disorder of the skin and mucous membranes. SJS/TEN causes widespread sloughing of the skin and mucous membranes causing ocular complications in the acute phase that can lead to life-long morbidity, including blindness. Patients with SJS/TEN commonly present with ocular inflammation in the acute phase which manifests as epithelial defects of the corneal epithelium, conjunctival epithelium, and/or eyelid margin. If the inflammation and epithelial sloughing in the acute phase is not managed appropriately, chronic ocular sequelae can result, ranging from dry eye to severe sicca with ocular surface keratinization and ankyloblepharon. Anywhere between 69–84% patients with SJS/TEN have ocular involvement in the acute phase.[1–5]

Amniotic membrane (AM) is the innermost layer of the placental fetal membranes. Processed AM can be used as a temporary bandage in inflammatory conditions of the ocular surface, including SJS/TEN and ocular burns, and provides anti-fibrotic and anti-angiogenic effects.[6] AM transplantation (AMT) within the first few days after onset of SJS/TEN was shown in one case to provide better long-term outcomes compared to AMT late in the phase of the acute disease [7] and in larger case series, to provide benefit especially when placed within the first 6 days after onset of symptoms.[8] AM can be transplanted by securing multiple 3.5 cm2 pieces to the eye and eyelids with sutures [9], but is significantly easier and faster when used as a single 5×10 cm sheet for each eye. Importantly, simply covering the cornea and limbal conjunctiva alone is inadequate for preventing long term consequences of SJS/TEN. Such procedures include the use of a single 3.5 cm2 piece of AM sutured at the limbus, or a Prokera® device (Bio-Tissue, Miami, FL) in which AM comes attached to a plastic symblepharon ring and is placed over the ocular surface like a contact lens with only topical anesthesia.[10, 11] These procedures do not address the eyelid margin disease seen in SJS/TEN and an AMT procedure which covers the eyelid margin is required.

A method of AMT using a 5×10cm sheet with the aid of sutures and bolsters at the eyelid margins under general anesthesia has been previously described.[9] However, in critically ill patients with SJS/TEN, general anesthesia may be prohibited. For those who can tolerate general anesthesia, the time, resources, and delay in treatment that general anesthesia requires can be significant. To facilitate expedient and relatively painless AMT, we describe a sutureless technique that obviates the need for general or local anesthesia.

Description of technique

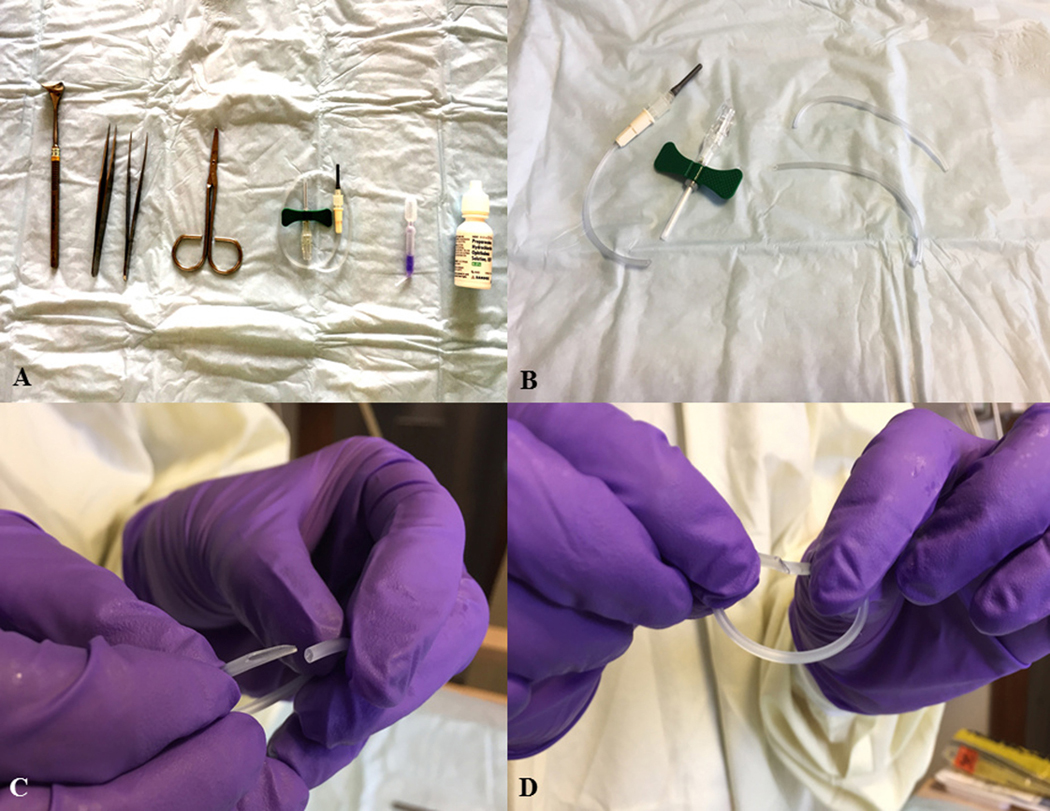

The AMT procedures were performed under intravenous sedation and with topical anesthesia from proparacaine hydrochloride ophthalmic eyedrops. The instruments required for the procedure are shown in Fig 1A. All 4 patients received AMT in both eyes as follows. First, the distance between the superior and the inferior forniceal rims is measured to estimate the appropriate diameter of the customized symblepharon ring which is fashioned from intravenous (IV) tubing (Ultra Small Bore Extension Sets, Reference Number MX453HL, Smiths Medical, Dublin, OH). One end of the IV tubing is cut with a straight edge while the other end is cut with an oblique beveled edge (Figure 1B). The oblique end is threaded into the straight edge (Figure 1C) to make a customized symblepharon ring (Figure 1D). The ring is then placed in the fornices for sizing to ensure it completely reaches the fornices without inducing lagophthalmos. The ring is then removed. Next, the periorbital skin is gently cleaned with povidone-iodine swabs, taking care to avoid inadvertent peeling of the skin from vigorous cleaning in the setting of fragile epidermis. Then, topical 5% povidone-iodine solution is placed on each eye. Though this is not a sterile procedure, sterile towels without adhesives can be used to drape each eye. The eyelashes are then removed from the superior and inferior eyelid (Figure 2A) and placement of the AMT can proceed.

Figure 1. Preparation for sutureless amniotic membrane transplantation (AMT).

(A) Instruments required from L-R, Desmarres lid retractor, two toothless forceps to hold the AM, scissors, intravenous (IV) tubing (can use that which accompanies a butterfly needle), cyanoacrylate glue, anesthetic eye drops. (B) Scissors are used to cut IV tubing for use as a customized symblepharon ring. (C) A bevelled cut is made on end of the tubing. (D) The beveled end of the tubing is threaded through the blunt end to create a customized symblepharon ring.

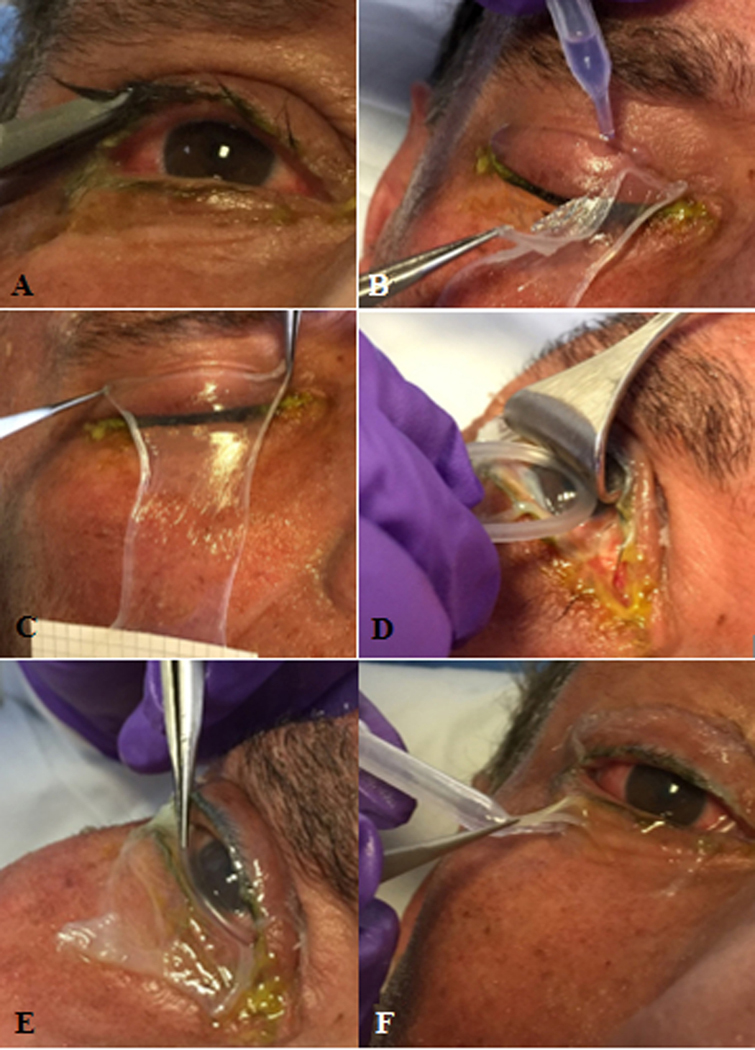

Figure 2. Procedure for sutureless amniotic membrane transplantation (AMT) in the right eye of a patient with Stevens-Johnson syndrome with ocular surface epithelial defects.

A) Upper and lower eyelashes are trimmed. B) Cyanoacrylate glue is used to secure the amniotic membrane (AM) sheet (5×10 cm) to the upper eyelid. Care is taken to ensure glue is placed at least 4mm above the eyelid margin. C) AM is held across the upper eyelid for 30 seconds to ensure adhesion. D) Desmarres lid retractor is used to retract the upper eyelid to allow the symblepharon ring to be placed in the superior fornix. E) The symblepharon ring is then tucked into the inferior fornix. F) The inferior margin of the AM is secured to the lower eyelid with cyanoacrylate glue. G) AM transplant is completed and secured to the eyelids and ocular surface. The patient should be able to close the eye without any lagophthalmos caused by the symblepharon ring.

In the acute SJS/TEN patient with moderate to severe ocular disease involving the eyelid margin, cornea and/or conjunctiva [4, 8, 12] a continuous 5 × 10 cm sheet of cryopreserved AM (Bio-Tissue, Miami, FL) is separated from the nitrocellulose paper at one edge and draped over the eyelid margins in a vertical orientation and with the epithelial basement membrane side up. Cyanoacrylate glue (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) is then placed underneath the AM on the upper eyelid skin several millimeters away from the eyelid margin, after reflecting the AM with forceps (Figure 2B). The AM is then held across the upper eyelid for 30 seconds with two forceps to ensure adhesion (Figure 2C). A Desmarres retractor is used to lift the upper eyelid off the ocular surface, and the custom symblepharon ring is used to push the AM into the superior fornix (Figure 2D) and then the inferior fornix (Figure 2E), with care to ensure the AM remains flat and unwrinkled under the symblepharon ring. A muscle hook is used to flatten and spread the AM into the desired position. Cyanoacrylate glue is then placed on the skin of the lower eyelid several mm away from the eyelid margin, and the AM is draped over the glue (Figure 2F). Excess AM beyond that attached to the eyelid margins is trimmed with scissors. Antibiotic ointment is applied over the eyelid and ocular surface, and the sterile drape removed. It should be ensured at this stage that the patient is able to close the eyelid and there is no lagophthalmos secondary to the symblepharon ring.

Standard ophthalmic care after AMT includes topical antibiotic and corticosteroid medications as previously reported.[12] Finally, the nursing team in charge of the patient’s care is notified to ensure the AM graft is left undisturbed; with no bolsters or sutures visible, it may be difficult for an untrained eye to recognize the presence of an AM. After the procedure, patients receive a daily ophthalmic evaluation to ensure that the AM remains in place.

Outcome data

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary. The study was conducted under Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliance and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Before the procedure, a written informed consent regarding the surgical procedure, risks, and benefits was obtained from each patient or legal guardian. A retrospective chart review identified 4 patients with acute SJS/TEN who received sutureless AMT, between March 1, 2017 and December 31, 2017, with follow-up ≥ 6 months after the procedure. All four patients had SJS/TEN confirmed by skin biopsy during the acute phase.

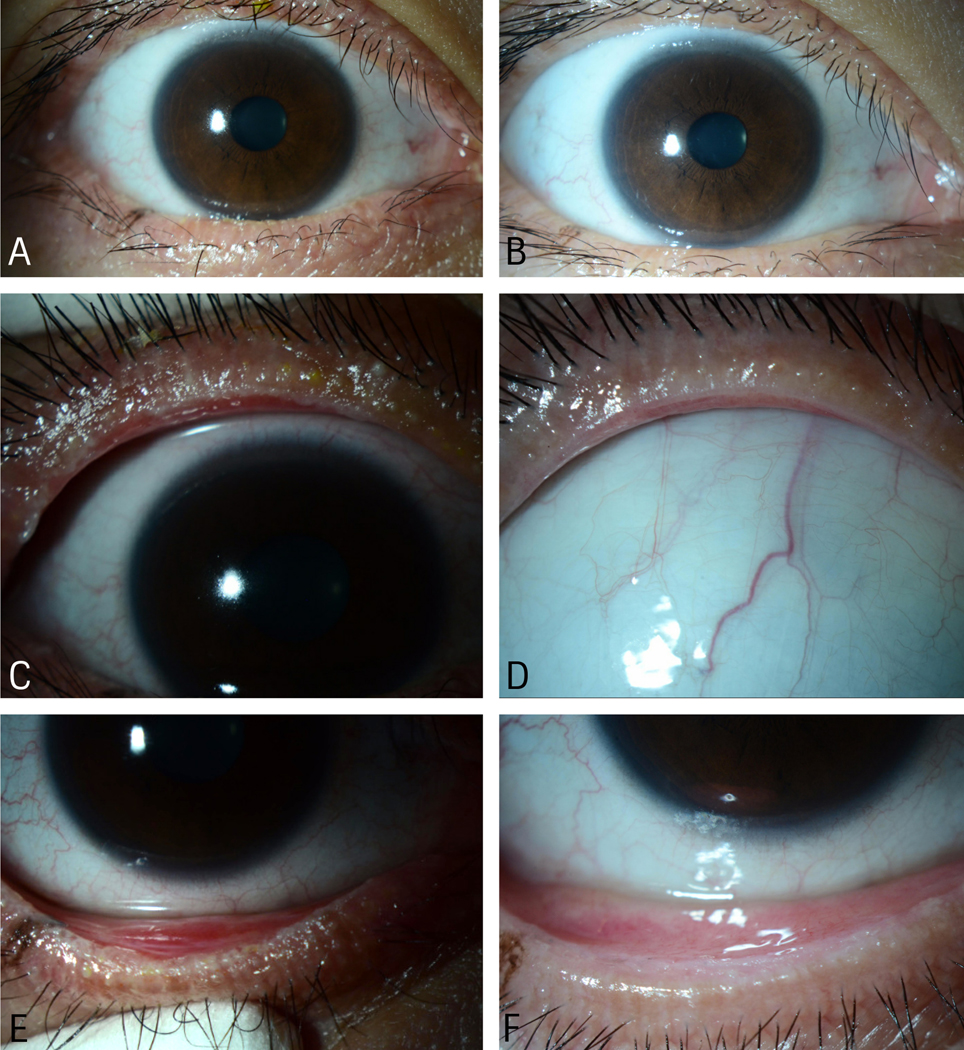

All four patients had grade 3 ocular involvement as defined by Sotozono and colleagues, with ocular surface and eyelid margin defects.[4] All four patients received AMT in both eyes, and all received prophylactic topical antibiotic and corticosteroid eyedrops, and topical corticosteroid ointment to the eyelid margin as previously described.[13] Systemic treatment included immunomodulatory medications in the acute phase for all four patients. Clinical details of the patients are mentioned in Table 1. Figure 3 depicts the right eye of Patient 4 in the sub-acute and chronic phases of SJS after AMT treatment. The mean follow-up after AMT was 12.75 months. Seven eyes of 4 patients retained BCVA of ≥ 20/40 at the last follow-up. The right eye of Patient 2 had a BCVA of 20/80 secondary to symblepharon extending to the corneal surface and neovascularization. This case is further described in the Discussion section.

Table 1.

Clinical details of four patients with acute ocular involvement of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) who underwent AMT with the technique using cyanoacrylate glue

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)/ Gender | 6/Female | 8/Female | 21/Female | 32/Female |

| Percentage of total BSA denuded | 30% | 30% | 10% | 25% |

| Presumed Etiology | Ibuprofen | Ibuprofen | Lamotrigine | Unknown |

| Visual acuity at presentation | RE 20/30, LE 20/25 | RE 20/20, LE 20/20 | RE 20/20, LE 20/25 | RE 20/20, LE 20/20 |

| Timing of AMT (days after onset of skin rash) | Day 4 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 3 |

| Ocular findings before AMT | UL desquamation of skin (BE), UL and LL margin ulceration (BE), central corneal epithelial defect (RE) | UL and LL desquamation of skin nasally (RE), BE UL and LL margin ulceration (BE), corneal epithelial defects (BE), inferior palpebral and bulbar conjunctival defects (RE) | UL margin ulceration (BE), temporal bulbar conjunctival defects (BE), palpebral conjunctival pseudomembranes (BE) | LL margin ulceration (BE), temporal bulbar conjunctival defects (BE) |

| Dissolution of AM | 6 days | 7 days | 6 days | 8 days |

| Ocular findings at last follow-up visit | irregular eyelid margin (BE), mild central LL eyelid margin keratinization (LE), tarsal conjunctival scarring (BE), meibomian gland dropout (BE) | irregular eyelid margin (BE), LL trichiasis (BE), UL and LL eyelid margin keratinization (BE), tarsal conjunctival scarring (BE), symblepharon and corneal neovascularization (RE), meibomian gland dropout | irregular eyelid margin (BE), meibomian gland disease (BE), mild LL eyelid margin keratinization (BE), tarsal conjunctival scarring (BE) | irregular eyelid margin (BE), meibomian gland disease (BE), UL and LL mild eyelid margin keratinization (BE), tarsal conjunctival scarring (BE), small symblepharon temporally (BE) |

| BCVA at last visit | RE 20/40, LE 20/40 | RE 20/80, LE 20/30 | RE 20/20, LE 20/25 | RE 20/20, LE 20/20 |

| Follow-up in months after AMT | 14 months | 15 months | 10 months | 12 months |

AM = amniotic membrane; AMT = amniotic membrane transplantation; BSA = body surface area; RE = right eye; LE = left eye; BE = both eyes; UL = upper lid; LL = lower lid; BCVA = best-corrected visual acuity

Figure 3. Ocular surface and eyelid disease of the right eye of Patient 4 after AMT in the acute phase of SJS.

A) Subacute phase image showing clear corneal surface and irregular lower eyelid margins and distichiatic eyelashes. B) Chronic phase image showing clear corneal surface and normal eyelid margin and less distichiatic eyelashes. C) Subacute phase image showing ulcerated upper eyelid margin, inflamed meibomian glands and tarsal conjunctiva, and early eyelid margin keratinization. D) Chronic phase image showing non-inflamed upper eyelid margin, conjunctiva, and meibomian glands. E) Subacute image showing irregular lower eyelid margin, inflamed meibomian glands and tarsal conjunctiva, and early eyelid margin keratinization. F) Chronic phase image showing non-inflamed and regular lower eyelid margin, meibomian glands, and conjunctiva

Discussion

Among SJS/TEN survivors, ocular complications cause the most disabling long-term sequelae.[14, 15] A role for AMT in minimizing ocular inflammation and protecting the eye in the acute phase of SJS/TEN was first reported in 2002.[16] Several studies, including multiple case series, a case-control study and a randomized controlled trial, have shown that AMT, when applied early in the course of acute AMT, can dramatically reduce long term ocular complications and morbidity.[8, 9, 11, 17, 18] It has been our practice to perform AMT in eyes of patients with acute SJS/TEN whose examination demonstrates eye findings to at least Sotozono grade 2.[4]

In our experience, AMT with suturing and bolsters can take several hours for both eyes. The combined use of a single 5×10cm sheet of AM, a custom IV tubing symblepharon ring, and cyanoacrylate glue to secure the AM to the eyelid margins permits rapid application of the AM (~20 minutes per eye), and can virtually eliminate the need for general anesthesia [8], even in the pediatric age group. Our series includes a 6-year-old and 8-year-old child, in whom bedside AMTs were easily performed. Providing general inhalational anesthesia for such a procedure in the acute phase of SJS/TEN can be problematic as a mask, oral airway, or endotracheal tube may aggravate the existing lesions or may compromise the airway by pushing tissue debris further into the respiratory passages.[19] Insertion of an oral airway or placing a mask over the face can also cause bleeding secondary to exacerbation of stomatitis and involvement of the skin of the face.[20] Additionally, patients with TEN may become rapidly hypothermic even in the controlled temperature environment of an operating room.[21]

To ensure every patient with significant ocular involvement receives AMT, we developed a novel technique of AM application. We cannot say that use of cyanoacrylate is superior in outcome to sutured eyelid bolsters as we have not compared the data between the two groups, only that it speeds AM application and causes less discomfort, allowing for a bedside procedure that eliminates the complications and complexities surrounding general anesthesia. Though we have not published outcomes between this glued AMT method and the sutured method, our preliminary data shows no difference in outcomes. Long-term ocular outcomes appear to be equivalent to published sutured AMT data. [8, 17] The right eye of Patient 2 had a poorer outcome than the others in this series. In our experience, eyes of the same patient can often have significantly different degrees of involvement from SJS/TEN. Even with AMT, eyes can still have poor outcomes. [17]. Most published studies on SJS/TEN do not go beyond 3 months of follow up and we believe significant ocular surface disease can occur between 3 and 24 months after the onset of SJS/TEN. Though the cause of a worse outcome in this eye cannot be definitively determined in this retrospective review, poor compliance with recommendations for eyelid margin surgery, as well as patient intolerance of PROSE devices, are thought to be primarily responsible for the degree of ocular surface disease.

The method we describe still achieves total coverage of the ocular surface, including the cornea and the bulbar, palpebral and forniceal conjunctiva, as well as the eyelid margin. Care does need to be taken to ensure the cyanoacrylate glue does not contact the ocular surface as it can be both toxic and abrasive, but this is easily achieved by application of the glue several millimeters away from the eyelid margin. Cyanoacrylate glue has been used successfully on the eyelid margin for temporary tarsorrhaphy in sedated and unconscious patients to prevent exposure keratopathy.[22]

Application of cyanoacrylate glue to the eyelids to secure the AM is easy to perform and does not cause bleeding as is commonly seen with sutures, possibly reducing inflammation. The skin to which it is applied epithelializes and does not scar. The glue can also be reapplied at the bedside if needed, for either a dislodged AMT, or in cases where a repeat AMT is deemed necessary.

Conclusion

Glued AMT in SJS/TEN offers an alternative to the traditional sutured AMT as a painless bedside procedure that can eliminate the need for general anesthesia and allow for delivery of expedient care. Long-term ocular outcomes appear to be equivalent to published sutured AMT data, though this needs to be systematically studied. As experience with this technique grows, additional data points can be studied and compared. However, given how rare yet severe SJS/TEN can be, we hope dissemination of this technique will allow for improved patient care, safety, and outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23EY028230. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None

References:

- [1].Gueudry J, Roujeau JC, Binaghi M, Soubrane G, Muraine M. Risk factors for the development of ocular complications of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Arch Dermatol 2009;145:157–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Yip LW, Thong BY, Lim J, Tan AW, Wong HB, Handa S, et al. Ocular manifestations and complications of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: an Asian series. Allergy 2007;62:527–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chang YS, Huang FC, Tseng SH, Hsu CK, Ho CL, Sheu HM. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis: acute ocular manifestations, causes, and management. Cornea 2007;26:123–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sotozono C, Ueta M, Nakatani E, Kitami A, Watanabe H, Sueki H, et al. Predictive factors associated with acute ocular involvement in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Am J Ophthalmol 2015;160:228–37.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Morales ME, Purdue GF, Verity SM, Arnoldo BD, Blomquist PH. Ophthalmic manifestations of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis and relation to SCORTEN. Am J Ophthalmol 2010;150:505–10.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tseng SC, Espana EM, Kawakita T, Di Pascuale MA, Li W, He H, et al. How does amniotic membrane work? Ocul Surf 2004;2:177–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ciralsky JB, Sippel KC. Prompt versus delayed amniotic membrane application in a patient with acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Clin Ophthalmol 2013;7:1031–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gregory DG. Treatment of acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis using amniotic membrane: a review of 10 consecutive cases. Ophthalmology 2011;118:908–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ma KN, Thanos A, Chodosh J, Shah AS, Mantagos IS. A Novel technique for amniotic membrane transplantation in patients with acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Ocul Surf 2016;14:31–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Shay E, Khadem JJ, Tseng SC. Efficacy and limitation of sutureless amniotic membrane transplantation for acute toxic epidermal necrolysis. Cornea 2010;29:359–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Shammas MC, Lai EC, Sarkar JS, Yang J, Starr CE, Sippel KC. Management of acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis utilizing amniotic membrane and topical corticosteroids. Am J Ophthalmol 2010;149:203–13 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kohanim S, Palioura S, Saeed HN, Akpek EK, Amescua G, Basu S, et al. Acute and chronic ophthalmic involvement in Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis - A comprehensive review and guide to therapy. II. Ophthalmic Disease. Ocul Surf 2016;14:168–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Saeed HN, Chodosh J. Ocular manifestations of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and their management. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2016;27:522–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Oplatek A, Brown K, Sen S, Halerz M, Supple K, Gamelli RL. Long-term follow-up of patients treated for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Burn Care Res 2006;27:26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Haber J, Hopman W, Gomez M, Cartotto R. Late outcomes in adult survivors of toxic epidermal necrolysis after treatment in a burn center. J Burn Care Rehabil 2005;26:33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].John T, Foulks GN, John ME, Cheng K, Hu D. Amniotic membrane in the surgical management of acute toxic epidermal necrolysis. Ophthalmology 2002;109:351–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hsu M, Jayaram A, Verner R, Lin A, Bouchard C. Indications and outcomes of amniotic membrane transplantation in the management of acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a case-control study. Cornea 2012;31:1394–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sharma N, Thenarasun SA, Kaur M, Pushker N, Khanna N, Agarwal T, et al. Adjuvant role of amniotic membrane transplantation in acute ocular Stevens-Johnson syndrome: A randomized control trial. Ophthalmology 2016;123:484–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kalhan SB, Ditto SR. Anesthetic management of a child with Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Cleve Clin J Med 1988;55:467–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Madan R, Chawla R, Dhar P, Saxena A, Dada VK. Anesthesia in Stevens Johnson syndrome. Indian Pediatr 1989;26:1038–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rabito SF, Sultana S, Konefal TS, Candido KD. Anesthetic management of toxic epidermal necrolysis: report of three adult cases. J Clin Anesth 2001;13:133–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Donnenfeld ED, Perry HD, Nelson DB. Cyanoacrylate temporary tarsorrhaphy in the management of corneal epithelial defects. Ophthalmic Surg 1991;22:591–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]