ABSTRACT

Glucose uptake assays commonly rely on the isotope-labeled sugar, which is associated with radioactive waste and exposure of the experimenter to radiation. Here, we show that the rapid decrease of the cytosolic pH after a glucose pulse to starved Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells is dependent on the rate of sugar uptake and can be used to determine the kinetic parameters of sugar transporters. The pH-sensitive green fluorescent protein variant pHluorin is employed as a genetically encoded biosensor to measure the rate of acidification as a proxy of transport velocity in real time. The measurements are performed in the hexose transporter-deficient (hxt0) strain EBY.VW4000 that has been previously used to characterize a plethora of sugar transporters from various organisms. Therefore, this method provides an isotope-free, fluorometric approach for kinetic characterization of hexose transporters in a well-established yeast expression system.

Keywords: glucose uptake assay, radiolabeled glucose, Michaelis–Menten constant, pHluorin, hexose transporters, hxt0 yeast

INTRODUCTION

As the entry point of central carbon metabolism, the transfer of sugars (mainly glucose) across cellular membranes is essential for cell survival in most life forms. Based on this premise, sugar transporters are regarded as promising drug targets to combat serious human diseases, including cancer and diabetes (Schmidl et al. 2018), or pathogens such as the malaria causative Plasmodium falciparum (Qureshi et al. 2020). Therefore, mechanisms and kinetics of sugar transporters are an object of intensive research. Current methods for measuring glucose uptake, mainly relying on isotope labeling, are cost intensive and necessitate specialized laboratories (Walsh et al. 1994a,b; Yamamoto et al. 2011). Furthermore, these experiments contribute to radioactive waste accumulation, a threat to human and environmental health that requires complex waste management strategies of governments and institutions (Poškas et al. 2019).

Isotope-free assays have also been described, employing the non-metabolizable glucose analog 2-deoxyglucose and externally added fluorogenic (Yamamoto et al. 2011) or bioluminescent (Valley et al. 2016) substrates. By using sugar analogs, the latter methods are not suitable for determining the kinetic parameters of the transporters. Here, we describe an alternative method, based on the intracellular pH change upon glucose uptake. The acidification of the yeast cytosol in response to a glucose pulse to glucose-starved cells is a well-known phenomenon (Ramos et al. 1989; Orij et al. 2009). During glucose starvation, the cytosolic pH (pHcyt) of yeast cells drops to ∼6 (Orij, Brul and Smits 2011). Under these conditions, the lack of glycolysis substrates diminishes ATP production, which leads to lower activities of the plasma membrane ATPase and the vacuolar V-ATPase, both of which consume ATP to translocate protons out of the cytosol (Orij, Brul and Smits 2011). When glucose is provided, it is transported across the plasma membrane and phosphorylated by the hexokinase as the first step of glycolysis. In this step, one molecule of ATP is hydrolyzed, and one proton is released (Fig. 1), causing the observed rapid additional acidification shortly after the glucose pulse (Ramos et al. 1989; Orij et al. 2009). Subsequently, a recovery of the neutral pHcyt up to pre-starvation conditions (pH = 7) (Reifenrath and Boles 2018) occurs, as glucose metabolism yields sufficient ATP to fuel the export of protons by the plasma membrane ATPase.

Figure 1.

Mechanism of cytosol acidification in yeast cells after a glucose pulse. Glucose is transported into the cell through a hexose transporter (Hxt) and immediately phosphorylated by the hexokinase. In this process, one molecule ATP per molecule glucose is hydrolyzed, releasing one proton and causing the drop of the pHcyt (see Fig. 2A; Figure S2, Supporting Information). With the progress of glycolysis, ATP is regenerated, fueling the plasma membrane ATPase Pma1, which actively transports protons out of the cell and thereby recovers the pHcyt. For simplicity, multiple glycolytic steps between glucose-6-phosphate and pyruvate are indicated by the dashed arrow and the stoichiometry is neglected.

Since the initial acidification is a direct consequence of glucose uptake, we reasoned that kinetics of both processes should be strongly correlated. For real-time measurements of the fast changes of pHcyt, we use the pH-sensitive green fluorescent protein (GFP) variant, the ratiometric pHluorin, which allows accurate and fast measurements in the pH range from 5.5 to 8 that were derived from emission intensity ratios from two different excitation wavelengths—390 and 470 nm (Miesenböck, Angelis and Rothman 1998; Orij et al. 2009). Importantly, overexpression of pHluorin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells does not affect the cellular metabolism (Orij et al. 2009) and a tuning of pHluorin expression levels can be neglected because of its ratiometric character (Kuhn, Rohrbach and Lanzer 2007), qualifying it as an ideal biosensor for our approach. Fluorescent dyes like fluorescein (Ramos et al. 1989), 2′7′-bis-2-carboxyethyl-5- (and -6)-carboxyfluorescein (BCECF) (Ozkan and Mutharasan 2002) or semi-naphthorhodafluor (SNARF) (Blank et al. 1992) are also often used to estimate intracellular pH but exhibit certain deficits like leakage of the dyes (Ozkan and Mutharasan 2002), the compartmentalization in particular cell types (Blank et al. 1992) or a loss of pH sensitivity over time (Weiner and Hamm 1989), in addition to considerable costs of these dyes. We developed the pHluorin-based assay in the well-established EBY.VW4000 hxt0 yeast strain, which lacks all endogenous transporters capable of hexose transport (i.e. Gal2, Hxt1-Hxt17, Agt1) (Wieczorke et al. 1999; Boles and Oreb 2018). Therefore, this strain is practically free of residual hexose uptake and has been used to express and characterize heterologous sugar transporters, including human Gluts (Boles and Oreb 2018).

RESULTS

Using pHluorin as a biosensor for time-resolved measurements of glucose uptake

With ratiometric pHluorin, the decrease of pHcyt is represented by a drop in the emission intensities ratio at 512 nm at the two excitation wavelengths 390 and 470 nm (R390/470) (Orij et al. 2009). For the purposes described in this study, we consider the time-dependent R390/470 decrease as an adequate kinetic parameter and its translation to pHcyt is therefore not necessary. Nevertheless, in initial experiments, we generated a calibration curve as described previously (Reifenrath and Boles 2018) for R390/470 values in the range from pH 5 to pH 9 (Figure S1, Supporting Information). The formula (indicated within the graph, see Figure S1, Supporting Information) confirmed the correlation between the R390/470 and pHcyt as published in previous studies (Orij et al. 2009; Reifenrath and Boles 2018) under our experimental conditions and it can therefore be used to estimate the pH range variation in the measurements shown below. We then demonstrated that the rapid changes of R390/470 can be measured in a time-resolved manner using the high-performance spectrofluorometer PTI QuantaMasterTM 8000 (HORIBA Scientific, Kyoto, Japan). We expressed pHluorin and the endogenous transporter Hxt5 (each from a separate multicopy plasmid) in the hxt0 yeast system EBY.VW4000 to avoid any interferences of the measurement with other hexose transporters. The use of multicopy plasmids for pHluorin expression has been established before (Orij et al. 2009; Reifenrath and Boles 2018), but expression levels of both, transporters and pHluorin, might vary under these circumstances (Lee et al. 2015). To take into account any putative variances due to expression levels or the physiological conditions of the cells, the average of biological triplicates was calculated for all experiments. The cells were grown on selective, low fluorescent maltose medium (see the 'Methods' section), and harvested and starved for 3.5 h. One minute after starting the fluorescence measurement, the cells were pulsed with 10 mM glucose, leading to the expected cytoplasm acidification. Within ∼10 s, a nearly linear decrease of R390/470 was observed (Fig. 2A), followed by a slower recovery phase. Moreover, the acidification rate was dependent on the glucose concentration (Fig. 2B), supporting the idea that it mirrors the velocity of glucose uptake.

Figure 2.

pHluorin-based measurement of acidification rate following a glucose pulse. The arrow indicates the time point of the glucose addition. (A) A fluorometric measurement of pHcyt changes after a glucose pulse to glucose-starved yeast cells. The change in the emission ratios (512 nm) at the two excitation wavelengths 390 and 470 nm (R390/470) of pHluorin serves as a proxy for the pHcyt change. The blue lines indicate the acidification phase in which the slope decreases linearly. Values from this phase were used to calculate the reciprocal R390/470 slope as a parameter of velocity. After the acidification phase, the R390/470 values rise gradually to the pre-starving state. The average from biological triplicates (EBY.VW4000 cells harboring the Hxt5 transporter, pulsed with 10 mM glucose) is shown exemplarily. Error bars are omitted for clarity. According to the calibration curve shown in Figure S1 (Supporting Information), the pHcyt decrease spans the range from 6.6 to 6.4 in these measurements. (B) The dependence of acidification velocity on glucose concentration. Indicated glucose concentrations were added to glucose-starved hxt0 yeast cells, expressing pHluorin and the transporter of interest (here Hxt5). The acidification velocity increases until reaching saturation.

To validate the hypothesis that the initial acidification after the glucose pulse is caused by the hexokinase-catalyzed phosphorylation of glucose (Ramos et al. 1989) under our experimental conditions, we tested pHluorin-expressing cells of the S. cerevisiae strain TSY11, which is devoid of all three yeast hexokinases (Subtil and Boles 2012). Indeed, the rapid, intense drop of pHcyt after the glucose pulse is absent in these cells but is recovered when HXK2, the predominant yeast hexokinase (Rodríguez et al. 2001), is reintroduced on a plasmid (Figure S2, Supporting Information). However, we observed a small residual decrease of R390/470 for hexokinase devoid cells (hxk0, TSY11; Subtil and Boles 2012), especially when pulsed with the higher concentration of 200 mM glucose. The same was also true for the hexose transporter devoid cells (hxt0, EBY.VW4000; Wieczorke et al. 1999) and even for cells that contain neither transporters nor kinases (hxt0/hxk0, AFY10; Farwick et al. 2014) (Figure S3A, Supporting Information). Also, the non-metabolizable sugar lactose induces this residual decrease of R390/470 (Figure S3B, Supporting Information), indicating that neither the sugar metabolism nor transport-related processes are the cause of this effect. More likely, the osmotic pressure that increases due to the addition of a sugar drives water out of the cell affecting the pHcyt in a concentration-dependent manner. Overall, this ‘background’ changes of pHcyt were low compared to those caused by glucose transport and—since they were dependent on the sugar concentration—we corrected the slopes measured in the presence of hexose transporters by subtracting the values measured for each glucose concentration in the absence of a transporter (i.e. the empty vector control) in subsequent analyses.

Suitability of the pHluorin-based method for determination of kinetic constants of glucose transporters

To evaluate the method as a tool for kinetic characterization of transporters, we selected three well-described yeast hexose transporters with glucose affinities differing within two orders of magnitude—Hxt1 (KM = 100 mM; Reifenberger, Boles and Ciriacy 1997; Roy et al. 2015), Hxt5 (KM = 6–10 mM; Diderich et al. 2001; Buziol et al. 2002) and Hxt7 (KM = 1–2 mM; Reifenberger, Boles and Ciriacy 1997). All three transporters were expressed from multicopy plasmids in EBY.VW4000 and the measurements were performed as described above. The slopes of the first time points after the pulse (as exemplified in Fig. 2A) at different glucose concentrations were determined, corrected as described above, and their reciprocal values (to avoid negative values) were plotted against respective glucose concentrations, revealing saturable kinetics (Fig. 3A–C). Fitting to the Michaelis–Menten equation produced the following apparent KM values for the transporters tested: 6.2 mM (Hxt1, Fig. 3A), 3.3 mM (Hxt5, Fig. 3B) and 1.3 mM (Hxt7, Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Glucose transport kinetics determined by the pHluorin-based assay. Michaelis–Menten constants (KM) of three prominent yeast hexose transporters Hxt1 (A), Hxt5 (B) and Hxt7 (C) were determined in the hxt0 strain background. Reciprocal values of the acidification slopes were plotted against the glucose concentration. Mean values and standard deviations were calculated from biological triplicates. The lines represent a least-square fit to the Michaelis–Menten equation. Determined KM values are indicated within the graphs.

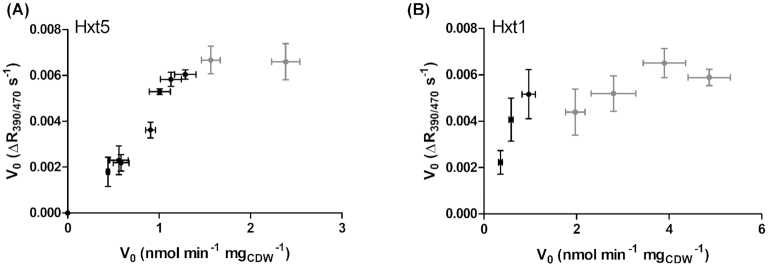

For Hxt7, the determined KM of 1.3 mM with this method is in agreement with the KM of 1–2 mM as determined by Reifenberger, Boles and Ciriacy (1997). However, the discrepancy between previously published data and the KM values of Hxt5 and (especially) Hxt1 determined by our method prompted us to re-determine the kinetics of these transporters using radiolabeled glucose but under conditions otherwise equal to those of the pHluorin-based assay (Figure S4A and B, Supporting Information). The results for Hxt1 (KM = 111.3 mM) confirmed those of Reifenberger, Boles and Ciriacy (1997) (KM = 100 mM) within the error range of the measurement. For Hxt5, we determined a slightly lower KM of 3.1 mM compared with the published values of 6.1 mM (Buziol et al. 2002) and 10 mM (Diderich et al. 2001). Strikingly, the KM values determined for Hxt5 with the pHluorin-based assay were in agreement with our results from the C14-glucose uptake assay, thereby, like the results for Hxt7, validating the new method. However, the measured KM values for Hxt1 obtained from the two methods still showed severe discrepancies. We, therefore, analyzed the correlation of V0 values measured by the pHluorin-based versus the radiolabeled glucose assay (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Correlation of initial transport velocity (V0) values measured with the pHluorin-based and radiolabeled glucose assays. V0 values measured by the radiolabeled glucose method are shown on the x-axes and those measured by the pHluorin-based assay on the y-axes, for the medium capacity transporter Hxt5 (A) and the high-capacity transporter Hxt1 (B). Error bars (standard deviation) of three replicates are shown. Correlation was calculated only for values below a threshold of 0.006 R390/470 s−1 or 1.5 nmol min−1 mgCDW−1 (excluding the data points that are colored grey).

A linear correlation is observed for both Hxt5 (r = 0.98) and Hxt1 (r = 0.96) up to a threshold at ∼0.006 R390/470 s−1 and 1.5 nmol min−1 mgCDW−1 (Fig. 4A and B), which apparently marks the upper limit of the acidification slope. We reasoned that the intrinsically high transport capacity of Hxt1 (Reifenberger, Boles and Ciriacy 1997), in combination with the expression from a strong promoter and a multicopy plasmid, could lead to approaching this threshold already at lower glucose concentration and, consequently, to an underestimation of the KM value. To test this hypothesis, we expressed Hxt1 on a low-copy plasmid (the CEN.ARS plasmid pUCPY1) and repeated the measurement of its glucose uptake kinetics (Fig. 5). By lowering its expression and, consequently, the number of transporters present at the plasma membrane, the transport capacity is diminished, reflected by lower R390/470 s−1 values (compare Figs 3A and 5).

Figure 5.

Glucose transport kinetics of the yeast hexose transporter Hxt1. The Michaelis–Menten constant (KM) was determined by the pHluorin-based assay with Hxt1 expressed on a low-copy CEN.ARS (pUCPY1) plasmid in the hxt0 strain background, and its value is indicated within the graph. Mean values and standard deviations of two (for 5, 50 and 100 mM) or three (for 10, 20, 200 and 400 mM) biological replicates are shown. The line represents a least-square fit to the Michaelis–Menten equation.

This experiment revealed a KM of 99.1 mM for the tested transporter (Fig. 5), matching both the published data (Reifenberger, Boles and Ciriacy 1997) and those from our radiolabeled glucose uptake assay (Figure S4A, Supporting Information) very well. It demonstrates that a very high Vmax value imposes an upper limit to the pHluorin-based method, likely since other factors than the transport might become rate-limiting and lead to underestimating transporter-saturating glucose concentrations. To test if hexokinase activity is a possible limiting factor, we overexpressed HXK2 along with HXT1 and pHluorin. However, despite a 3.6-fold increase in hexokinase activity (Figure S5A, Supporting Information), the apparent KM value of Hxt1 expressed from a multicopy plasmid was still underestimated (Figure S5B and C, Supporting Information). Hence, as the phosphorylation of glucose is ATP dependent, rapid ATP depletion is a likely explanation for our observation. However, we cannot rule out other bottlenecks, e.g. in the downstream glycolytic reactions.

DISCUSSION

The most commonly used method for determining glucose uptake in yeast (Boles and Oreb 2018) requires radiolabeled (14C) sugar and includes the following steps: (i) incubation of the cells with the sugar solution; (ii) quenching with an excess of unlabeled sugar; (iii) collecting the cells by filtering; (iv) washing (twice) the filter; (v) inserting the filter into a scintillation vial and (vi) measurement using a scintillation counter. The hands-on time requirement for steps (i)–(v) is considerable (∼2–3 min per sample), adding up to 60–90 min of work necessary for a typical determination of the KM value for each transporter. Moreover, scintillation counting requires 10 min per sample, and obtaining the raw data for the complete dataset is only possible after several hours (e.g. 5 h for a typical KM determination/30 samples). Our new method reduces the handling time and raw data collection to ∼90 min for the same number of samples. Importantly, signal acquisition can be monitored in real-time, enabling data quality control during the measurement, in contrast to 14C assays that can be evaluated only a posteriori. Also, the pHluorin assay substantially reduces the costs for consumables, as no radiochemicals, filters, scintillation liquid and scintillation vials are necessary. Radiochemicals are not only expensive themselves, but their handling, storage and disposal requires specialized laboratories and spaces, associated with substantial costs and administrative effort. Most importantly, the pHluorin-based method avoids the exposure of the experimenter to radiation and radioactive waste production.

It should be noted that the hexokinase-dependence cannot be regarded as a particular disadvantage of the pHluorin-based assay; previous work by others has shown that the uptake of (14C-labeled) phosphorylatable sugars is dependent on intracellular ATP concentration (Walsh, Smits and van Dam 1994c) and hexokinase activity (Smits et al. 1996), when the assays are performed on the 5-s timescale, according to the common protocol (Boles and Oreb 2018). In fact, hexose phosphorylation prevents the accumulation of intracellular sugar, which would—due to the breakdown of the concentration gradient across the membrane—cause an underestimation of the transport rates, especially for facilitative transporters, as it has been observed in hexokinase-deficient cells (Smits et al. 1996). The authors demonstrated that for determination of the ‘true’ initial velocity of sugar uptake, which is not dependent on the events downstream of the transport, the assays must be performed on the 200-ms timescale using the so-called quench-flow technique (Walsh, Smits and van Dam 1994c). Nevertheless, the kinetic constants of sugar uptake measured in wild-type (hexokinase expressing) cells were comparable on both timescales (Smits et al. 1996), demonstrating that a fairly good approximation of the transport kinetics can be obtained even on the 5-s timescale, if the sugar transport does not exceed the capacity of sugar phosphorylation. This is consistent with our observation that the upper limit of the accuracy of the pHluorin assay is determined by the capacity (Vmax) of the transporter, since a very high uptake rate leads to a saturation of the system and underestimation of the KM value, as shown here for Hxt1 when expressed from a multicopy plasmid. Based on correlation analyses (Fig. 4), we determined a threshold value of 0.006 R390/470 s−1 (corresponding to 1.5 nmol min−1 mgCDW−1 with the radiolabeled glucose uptake assay), after which the pHluorin-based assay becomes inaccurate for determination of kinetic constants in EBY.VW4000 cells. By defining the threshold value within the method itself, no a priori knowledge about the transport capacity for a particular transporter is necessary. If the upper limit is reached, low copy plasmids (as shown for Hxt1, Fig. 5), a genomic integration, weak or regulatable promoters can be applied to reduce the expression and, thereby, allow for an accurate measurement. However, if the determination of transport rates of, for example, wild-type strains (and not plasmid-expressed transporters in the hxt0 strain) is desired, transport capacities cannot be altered, which restricts the applicability of our method. Also, the prerequisite of using starved cells precludes the possibility to measure transport rates in growing cells. However, in this context it is noteworthy that all available sugar uptake assays require washing of the cells and storing them in a sugar-free solution prior to the measurement, which also likely induces starvation-like changes of cellular physiology.

In starved EBY.VW4000 cells, we have shown for three model transporters that the KM values (spanning the range from 1 to 100 mM) can be accurately determined with the pHluorin-based method. Whereas the KM value is an intrinsic property (a kinetic constant) of each transporter, the Vmax is variable, as it depends on the protein abundance (i.e. the expression level) of the transporter. Nevertheless, in some circumstances, it is desirable to determine the Vmax, e.g. for comparative purposes. Based on the strong correlation shown in Fig. 4, linear regression (Formula: [nmol min−1 mgCDW−1] = [R390/470 s−1]/0.00466) can be used to interconvert the values, at least under experimental conditions comparable to those applied here (i.e. regarding strain background, hexokinase levels and preculture conditions). For validation of the assay conditions in other laboratories, we recommend including at least one transporter plasmid used in this study as a control. While adapting the expression levels of transporters must be considered due to the above-mentioned reasons, the signal sensitivity of measurements should not be influenced by the expression level of pHluorin. Due to their ratiometric character, pHluorin-based measurements are independent of the biosensor concentration and not affected by artefacts such as bleaching (Kuhn, Rohrbach and Lanzer 2007). In previous studies, a super-folder pHluorin was expressed in S. cerevisiae cells under the control of the repressible promoter MET25 and pH calibration was performed (as in this study, see the 'Methods' section) for cells grown under fully inducible conditions (no methionine) and partly repressible conditions (0.1 mM methionine) (Reifenrath and Boles 2018). The sigmoidal-dose response fits of both experiments were in agreement within the error range (Reifenrath and Boles 2018), further indicating that the quantity of pHluorin molecules is not a relevant factor. In summary, the pHluorin-based method provides a comparably accurate, but simpler, faster, cheaper and safer alternative to the common 14C-based method for measuring uptake of glucose and other phosphorylatable sugars, which account for the preferred and largest fraction of carbohydrates used by living organisms, including humans and most human pathogens. In combination with the widely used hxt0 background, this approach can be applied to characterize all heterologous transporters that can be functionally expressed in yeast.

METHODS

Strains and media

The construction of S. cerevisiae strains EBY.VW4000 (hxt0), TSY11 (hxk0) and AFY10 (hxt0/hxk0) was reported previously (Wieczorke et al. 1999; Subtil and Boles 2012; Farwick et al. 2014). Plasmid-free cells were grown in standard YEP-media (1% (w/v) yeast extract, 2% (w/v) peptone) supplemented with 1% (w/v) maltose (for EBY.VW4000 cells) or 2% (v/v) ethanol (for TSY11 and AFY10 cells) for maintenance and preparation of competent cells. Frozen competent cells were prepared and transformed according to Gietz and Schiestl (2007). The transformants were plated on solid, selective synthetic complete (SC) medium (Bruder et al. 2016) with 1% (w/v) maltose (SCM) or 2% (v/v) ethanol (SCEtOH), where leucine, uracil or histidine were omitted as required for the selection of the plasmids. Filter-sterilized, low fluorescent, synthetic complete medium (lf-SC) containing 6.9 g/L YNB with ammonium sulfate, without amino acids, without folic acid and without riboflavin (MP Biomedicals), containing 1% (w/v) maltose or 2% (v/v) ethanol and amino acids as stated in Bruder et al. (2016), in which the respective amino acid(s) were omitted, was used for cultivation of cultures for the pHluorin measurements. For subcloning of plasmids, E. coli strain DH10B (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) was used.

Plasmid construction

For plasmid assembly, the vector backbone p425H7 (for pHluorin), p426H7 (for all applied transporters or HXK2), pUCPY1 (to express Hxt1 with lower capacity) and p423H7 (for HXT1 in the HXK2 overexpression experiment) were linearized with restriction enzymes BamH1 and EcoR1 (New England Biolabs GmbH). The backbones were transformed together with the corresponding PCR fragment in EBY.VW4000 for homologous recombination, according to Oldenburg et al. (1997). All genes applied in this study were under the control of the strong, constitutive, truncated HXT7−1–392 promoter and the CYC1 terminator. PCRs were performed with Phusion polymerase (New England Biolabs GmbH) and primers listed in Table S1 (Supporting Information). The plasmids are listed in Table S2 (Supporting Information).

Calibration of pHluorin

EBY.VW4000 cells expressing pHluorin on the multicopy p425H7 plasmid were grown overnight in 15 mL lf-SC-LEU medium containing maltose (1%, w/v) and harvested the next day in the exponential growth phase at an OD600nm of 0.5–1.5. The pellets were resuspended in PBS buffer (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4) containing 100 µg/mL digitonin and incubated 10 min on ice to permeabilize the cell wall as described by Orij et al. (2009). Thereafter, cells were washed twice and resuspended in PBS. pH calibration was performed as described in Reifenrath and Boles (2018), where the cells were added (to a final OD600nm = 0.5) to citric acid/Na2HPO4 buffer solutions, with different pH values ranging from 5.0 to 9.0. The cell/buffer suspensions were transferred into a black polystyrene clear-bottom 96-well microtitre plate (Greiner Bio One, article Nr. 655 097) and mounted onto the CLARIOstar microplate reader (BMG LABTECH GmbH) (set at 30°C) to measure the emission intensities at 512 nm when excited at 390 nm or 470 nm, respectively, to calculate the ratio R390/470. Data from biological triplicates was analyzed with the sigmoidal dose-response fit in GraphPad Prism 5.

The pHluorin-based assay and data analysis

To test the response of a sugar-pulse to sugar-starved cells, 15 mL of selective lf-SCM (or lf-SC-EtOH) medium was inoculated with the transformed cells in biological triplicates, and grown overnight in 100-mL Erlenmeyer flasks at 30°C and 180 rpm. On the next day, the cultures were harvested in the exponential growth phase (at an OD600nm between 0.5 and 1.5). Cells were washed twice with double-distilled water and resuspended in the lf-SC medium without any carbon source to a final OD600nm of 1. These suspensions were incubated at 30°C and 180 rpm in Erlenmeyer flasks for 3.5–4 h to induce starvation.

To monitor the effect of a sugar pulse to sugar-starved cells on the intracellular pH, we used a PTI QuantaMaster 8000 Spectrofluorometer (Model QM-8075-11-C, HORIBA Scientific). After starvation, 1800 µL of the cell suspension was transferred into a macro cell quartz-glass cuvette (type 100-QS, layer thickness 10 mm, volume 3.5 mL, Hellma Analytics) together with a magnetic stirring bar (3 mm × 6 mm, Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were kept in a water bath at 30°C until just before the measurement, and the temperature in the fluorometer was set to 30°C. The cuvette was mounted into the sample compartment, and the lid, which contained a sample port, was closed. The magnetic stirring function was switched on and adjusted to medium velocity. Integration time was set to 0.5 s, and slit widths were set to 3 nm. The measurement was performed by exciting the samples successively at the two excitation wavelengths 390 and 470 nm and recording the emission intensity at 512 nm. The ratio of these intensities (R390/470) was calculated and plotted on-line during the measurement, presenting one R390/470 value every 2.2 s. After 60 s, 200 µL of the 10× sugar solution was injected through the port into the cuvette with a Hamilton syringe (500 µL, Sigma-Aldrich) and the R390/470 value was recorded for another 3 min. After a total time of 4 min, the cuvette was removed from the device. For the determination of transport kinetics, this measurement was performed in biological triplicates for the following final glucose concentrations: 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200 and 400 mM (for Hxt1, for HXK2 overexpression experiments, 400 mM was omitted); 1, 1.5, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50 and 100 mM (for Hxt5); and 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100 and 200 mM (for Hxt7).

For each derived data set, the time frame after the glucose pulse, in which R390/470 decreased linearly, was identified. In this time frame, the slope (ΔR390/470/Δt) was calculated and multiplied by −1 to obtain positive values (for plotting over glucose concentrations for Michaelis–Menten analysis). The same was done with the data sets derived from the empty vector control (pHluorin-expressing EBY.VW4000 cells without any transporter), pulsed with the corresponding glucose concentration, and the average from triplicates was calculated. The corresponding empty vector control average values were subtracted for each glucose concentration from slopes obtained in transporter measurements to correct for the background change of R390/470 (see Figure S3, Supporting Information). The values were plotted against glucose concentrations and analyzed by nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prism 5 to calculate the KM parameter.

Radiolabeled glucose uptake assay

KM values for Hxt1 and Hxt5 were also determined by the conventional uptake assay using radiolabeled glucose to compare the results with the KM values derived from the pHluorin-based assay. Precultures expressing pHluorin and concomitantly either HXT1 or HXT5 on a multicopy plasmid were grown for 6 h in 30 mL lf-SCM medium, in which leucine and uracil were omitted, in a 300-mL Erlenmeyer flask. Pre-grown cells were transferred to pre-warmed lf-SCM medium, without leucine or uracil, to a total volume of 200 mL, in 2-L Erlenmeyer flasks. Despite the larger volume of the culture, cells were grown overnight under the same conditions as applied for the pHluorin-based assay (30°C, 180 rpm) and harvested on the next day in the early exponential growth phase (at an OD600nm between 0.5 and 1.5). Cells were washed twice with double-distilled water and resuspended in selective lf-SC medium without any carbon source to a final OD600nm = 1. Cell suspensions were incubated at 30°C and 180 rpm in 1-L Erlenmeyer flasks for 3.5–4 h to induce starvation. After this time, cells were transferred to 50-mL Falcon tubes, of which the empty weight has been determined before to later calculate the cell fresh and dry weight, and centrifuged (4000 × g, 5 min, 20°C). Pellets were washed once in ice-cold 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (KH2PO4, pH 6.5, adjusted with KOH). After another centrifugation (4000 × g, 5 min, 4°C), the supernatant was discarded; the pellet was weighed and resuspended in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer to a wet-weight concentration of 60 mg/mL. One hundred ten microlitre aliquots of these cell suspensions were prepared and kept on ice. The volume of the leftover cell suspension was determined, and cells were centrifuged (4000 × g, 5 min, 4°C). The pellet was frozen at −80°C overnight or longer to prepare for freeze drying. The procedure of the uptake assay, the freeze drying and the calculation of data have been described previously in detail by Boles and Oreb (Boles and Oreb 2018). The measured uptake velocity was expressed as nmol C14 glucose taken up per minute per milligram cell dry weight (nmol min−1 mgCDW−1). The cell suspension–radiolabeled glucose mixture was incubated for only 5 s before application to the membrane filter. Uptake was measured at glucose concentrations 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200 and 400 mM (for Hxt1) and 1, 1.5, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100 and 200 mM (for Hxt5).

Calculation of the KM and the Vmax was done by nonlinear regression analysis and global curve fitting in Prism 5 (GraphPad Software) with values from technical triplicates.

Preparation of protein crude extracts

To produce crude extracts, EBY.VW4000 cells expressing HXK2 on the high-copy p426H7 plasmid as well as EBY.VW4000 and TSY11 cells containing an empty p426H7 plasmid as controls were grown overnight in 30 mL SC medium without uracil and with 1% (w/v) maltose (for EBY.VW4000 cells) or 2% (w/v) galactose (for TSY11 cells). Cells were harvested at the exponential phase (at an OD600nm between 2 and 3), transferred in 50-mL Falcon tubes and centrifuged (4000 × g, 10 min, 20°C). Pellets were washed twice in double-distilled water and transferred to 2-mL Eppendorf reaction tubes during the second washing step. The pellets were suspended in 1× pellet volume of 50-mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.6, adjusted with KOH), containing 1× Halt Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Fisher) and 1 mM PMSF (Sigma-Aldrich) to prevent proteolytic degradation. The same volume glass beads (0.25–0.5 mm, Roth) were added, and cells were disrupted by vortexing on the vibrax for 10 min at 4°C. After centrifugation (13000 × g, 5 min, 4°C), the supernatant was transferred to a fresh Eppendorf reaction tube and kept on ice. Protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay (Bradford 1976).

Enzyme activity assay

Hexokinase activity was assayed, in technical triplicates, based on the coupled reaction of the hexokinase and the glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6P-DH), releasing NADPH + H+. The accumulation of NADPH + H+ can be quantified photometrically as an increase of the absorption at 340 nm (Bergmeyer 1974).

The following components of the assay were pre-mixed in cold 50-mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.6, adjusted with KOH) and stored on ice: glucose (217 mM), MgCl2 (8 mM), NADP (1.027 mM), ATP (0.71 mM) and G6P-DH (0.11 units/reaction). One hundred ninety microlitres of the mix was dispensed in a cuvette (UV-Cuvette micro, Brand) and incubated in the photometer (Ultrospec 2100 pro, Amersham Biosciences), which was pre-warmed to 30°C, for 2 min. Ten microlitres of the crude extract was added, and the sample was mixed thoroughly by pipetting up and down. A continuous measurement of the absorption at OD340nm was started and stopped after ∼10 min, when no increase of OD340nm was observed anymore. Specific activity was calculated from the slope (ΔOD340nm/Δt) (Bergmeyer 1974), taking into account the determined protein concentration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Eckhard Boles and Sebastian Tamayo Rojas for support and stimulating discussions.

FUNDING

Financial support by the NIH (grant number R01-GM123103 to JC and MO) and the Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds (travel grant to SS) is gratefully acknowledged.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Sina Schmidl, Institute of Molecular Biosciences, Faculty of Biological Sciences, Goethe University Frankfurt, 60438 Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Cristina V Iancu, Department of Chemistry, East Carolina Diabetes and Obesity Institute, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC27834, USA.

Mara Reifenrath, Institute of Molecular Biosciences, Faculty of Biological Sciences, Goethe University Frankfurt, 60438 Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Jun-yong Choe, Department of Chemistry, East Carolina Diabetes and Obesity Institute, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC27834, USA.

Mislav Oreb, Institute of Molecular Biosciences, Faculty of Biological Sciences, Goethe University Frankfurt, 60438 Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

SS performed the experiments, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. CVI helped with the experiments. MR suggested using pHluorin as a sensor for glucose uptake. JC provided advice and resources. MO conceived the kinetic analysis approach and guided the project. All authors edited and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Bergmeyer HU. Methoden der enzymatischen Analyse. Ch 4, 3rd edn Weinheim: Verlag Chemie GmbH, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Blank PS, Silverman HS, Chung OY et al. Cytosolic pH measurements in single cardiac myocytes using carboxy-seminaphthorhodafluor-1. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:H276–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boles E, Oreb M. A growth-based screening system for hexose transporters in yeast. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1713:123–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein–dye binding. Anal Chem. 1976;72:248–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruder S, Reifenrath M, Thomik T et al. Parallelised online biomass monitoring in shake flasks enables efficient strain and carbon source dependent growth characterisation of Saccharomycescerevisiae. Microb Cell Fact. 2016;15:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buziol S, Becker J, Baumeister A. et al. Determination of in vivo kinetics of the starvation-induced Hxt5 glucose transporter of Saccharomycescerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 2002;2:283–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diderich JA, Schuurmans JM, van Gaalen MC et al. Functional analysis of the hexose transporter homologue HXT5 in Saccharomycescerevisiae. Yeast. 2001;18:1515–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farwick A, Bruder S, Schadeweg V et al. Engineering of yeast hexose transporters to transport D-xylose without inhibition by D-glucose. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:5159–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz RD, Schiestl RH.. Frozen competent yeast cells that can be transformed with high efficiency using the LiAc/SS carrier DNA/PEG method. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn Y, Rohrbach P, Lanzer M. Quantitative pH measurements in Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes using pHluorin. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:1004–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ME, DeLoache WC, Cervantes B et al. A highly characterized yeast toolkit for modular, multipart assembly. ACS Synth Biol. 2015;9:975–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miesenböck G, Angelis DA, Rothman JE. Visualizing secretion and synaptic transmission with pH-sensitive green fluorescent proteins. Nature. 1998;394:192–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldenburg K, Vo KT, Michaelis S et al. Recombination-mediated PCR-directed plasmid construction in vivo in yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:451–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orij R, Brul S, Smits GJ. Intracellular pH is a tightly controlled signal in yeast. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1810:933–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orij R, Postmus J, Ter Beek A et al. In vivo measurement of cytosolic and mitochondrial pH using a pH-sensitive GFP derivative in Saccharomycescerevisiae reveals a relation between intracellular pH and growth. Microbiology. 2009;155:268–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan P, Mutharasan R. A rapid method for measuring intracellular pH using BCECF-AM. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1572:143–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poškas P, Kilda R, Šimonis A et al. Disposal of very low-level radioactive waste: Lithuanian case on the approach and long-term safety aspects. Sci Total Environ. 2019;667:464–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi AA, Suades A, Matsuoka R et al. The molecular basis for sugar import in malaria parasites. Nature. 2020;578:321–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos S, Balbin M, Raposo M et al. The mechanism of intracellular acidification induced by glucose in Saccharomycescerevisiae. J Gen Microbiol. 1989;135:2413–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reifenberger E, Boles E, Ciriacy M. Kinetic characterization of individual hexose transporters of Saccharomycescerevisiae and their relation to the triggering mechanisms of glucose repression. Eur J Biochem. 1997;245:324–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reifenrath M, Boles E. A superfolder variant of pH-sensitive pHluorin for in vivo pH measurements in the endoplasmatic reticulum. Sci Rep. 2018;8:11985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez A, Cera T de La, Herrero P et al. The hexokinase 2 protein regulates the expression of theGLK1, HXK1 and HXK2 genes of Saccharomycescerevisiae. Biochem J. 2001;355:625–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A, Dement AD, Cho KH et al. Assessing glucose uptake through the yeast hexose transporter 1 (Hxt1). PLoS One. 2015, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidl S, Iancu CV, Choe J-y et al. Ligand screening systems for human glucose transporters as tools in drug discovery. Front Chem. 2018;6:183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits HP, Smits GJ, Postma PW et al. High-affinity glucose uptake in Saccharomycescerevisiae is not dependent on the presence of glucose-phosphorylating enzymes. Yeast. 1996;12:439–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subtil T, Boles E. Competition between pentoses and glucose during uptake and catabolism in recombinant Saccharomycescerevisiae. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2012;5:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valley MP, Karassina N, Aoyama N et al. A bioluminescent assay for measuring glucose uptake. Anal Biochem. 2016;505:43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh MC, Smits HP, Scholte M et al. Affinity of glucose transport in Saccharomycescerevisiae is modulated during growth on glucose. J Bacteriol. 1994a;176:953–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh MC, Smits HP, Scholte M et al. Rapid kinetics of glucose uptake in Saccharomycescerevisiae. Folia Microbiol. 1994b;39:557–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh MC, Smits HP, van Dam K. Respiratory inhibitors affect incorporation of glucose into Saccharomycescerevisiae cells, but not the activity of glucose transport. Yeast. 1994c;10:1553–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner ID, Hamm LL. Use of fluorescent dye BCECF to measure intracellular pH in cortical collecting tubule. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:F957–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorke R, Krampe S, Weierstall T et al. Concurrent knock-out of at least 20 transporter genes is required to block uptake of hexoses in Saccharomycescerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1999;464:123–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto N, Ueda M, Sato T et al. Measurement of glucose uptake in cultured cells. Curr Protoc Pharmacol. 2011, DOI: 10.1002/0471141755.ph1214s55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.