Abstract

Background/Aim: The discovery of the nude mouse model enabled the experimental growth of human-patient tumors. However, the low establishment rate of tumors in nude and other immunodeficient strains of mice has limited wide-spread clinical use. Materials and Methods: In order to increase the establishment rate of surgical specimens of patient tumors, we transplanted tumors to nude mice subcutaneously along with large amounts of surrounding tissue of the tumor. Results: The new transplantation method increased the establishment rate in nude mice to 66% compared to the old method of implanting the surgical tumor specimen with surrounding tissue removed (14%). High stage and presence of metastasis in the patient donor are positively correlated to tumor engraftment in nude mice. Conclusion: The new method can potentially allow most cancer patients who undergo surgery or biopsy to have their own mouse model for drug-sensitivity testing.

Keywords: Patient-derived xenograft, PDX, patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX), nude mice, tumor implantation, surrounding tissue, co-implantation, take rate, individualized medicine, gynecological cancer, breast cancer

Cancer-drug sensitivity depends on the individual characteristics of the patient’s tumor. Therefore, cancer chemotherapy needs to be individualized (1,2). Rygaard was the first to successfully transplant and grow surgical cancer specimens in nude mice in 1969 (3). The surgical specimens were transplanted subcutaneously in the nude mice. Laboratories in the United States, Europe, China and Japan adopted this method and it is in use today under the term patient-derived xenograft (PDX) (4). However, since the time of Rygaard, there has not been a significant increase in the establishment frequency of human tumors in nude and other immune-deficient mice, which has inhibited the use of PDX models for individualized cancer therapy. The standard implantation technique is to first remove the surrounding tissue from the surgical cancer specimen. In the present report we describe a novel approach of co-implanting the tumor along with large amounts of surrounding tissue into a pocket made in the subcutaneous space of nude mice. The new method greatly increased the establishment frequency of patient tumors in nude mice, that should enable its wide-spread clinical use.

Materials and Methods

Athymic nude mice (AntiCancer Japan Inc, Narita, Japan) were used for tumor implantation. All procedures followed ethical procedures for use of experimental animals. All patients provided written informed consent for implantation of their tumors in nude mice under the Institutional Review Board approval of Kawasaki Medical School, Kurashiki, Japan. Tumors collected at surgery were placed in DMEM at 4˚C and cooled on ice until transplantation at the AntiCancer Japan Laboratories.

Subcutaneous transplantation of patient tumors was performed in the back-skin of nude mice under anesthesia. A skin incision of approximately 1 cm was made and the tumors and surrounding tissue derived from the patient were inserted into a deep pocket formed by the incision in the subcutaneous space. As a comparison some tumors were transplanted in which the surrounding tissue was removed as much as possible, so that only the tumor was transplanted.

The transplanted tumors were observed for 12 weeks or longer to confirm engraftment.

Results

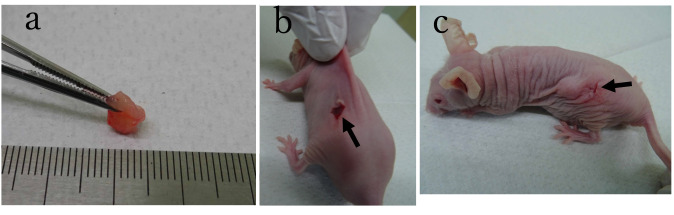

The method of tumor co-implantation along with extensive surrounding tissues is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Method of co-transplantation of tumor and surrounding tissue. (a) Representative patient-derived tumor specimen with a large amount of surrounding tissue. (b) Tumor specimen and surrounding tissue were inserted into a pocket in the subcutaneous space through an incision indicated by arrow. (c) Immediately after tumor and surrounding tissue were inserted in the subcutaneous pocket.

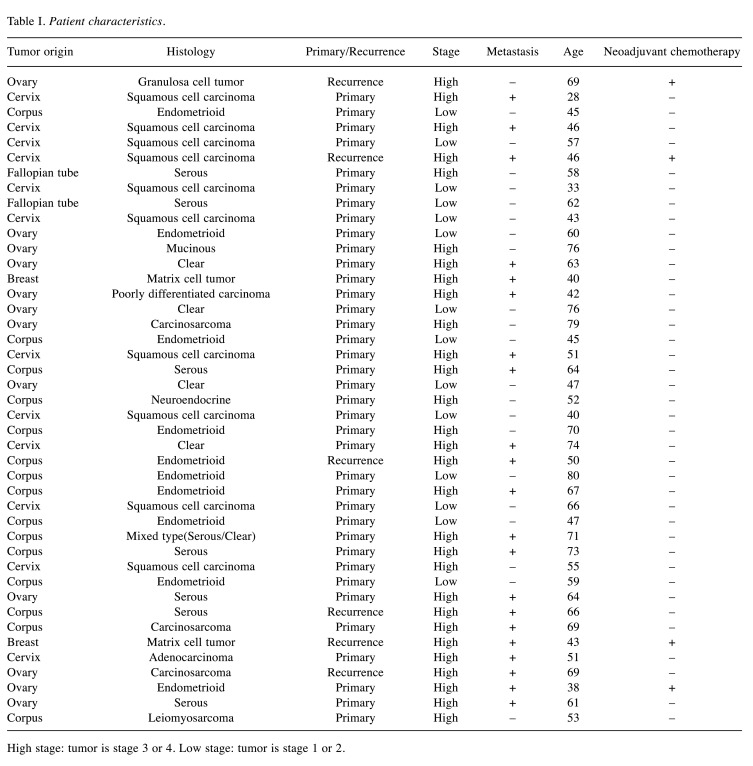

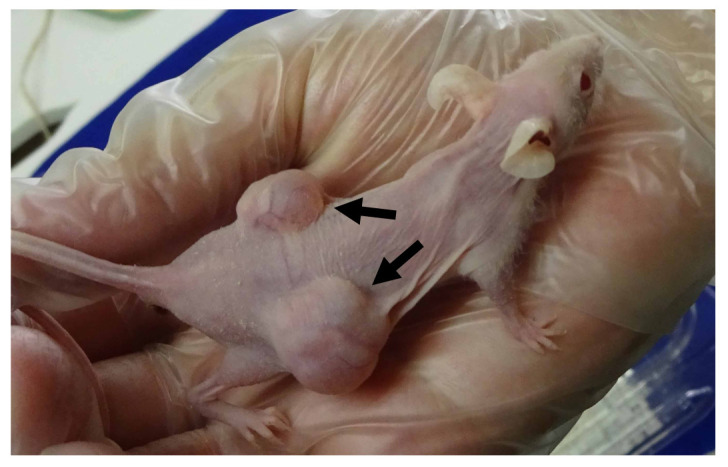

From 2015 to the present, tumor implantation in nude mice was performed for 43 cases, including 41 cases of gynecologic malignancy and 2 cases of breast cancer. Table I shows the characteristics of the patients.

Table I. Patient characteristics.

High stage: tumor is stage 3 or 4. Low stage: tumor is stage 1 or 2.

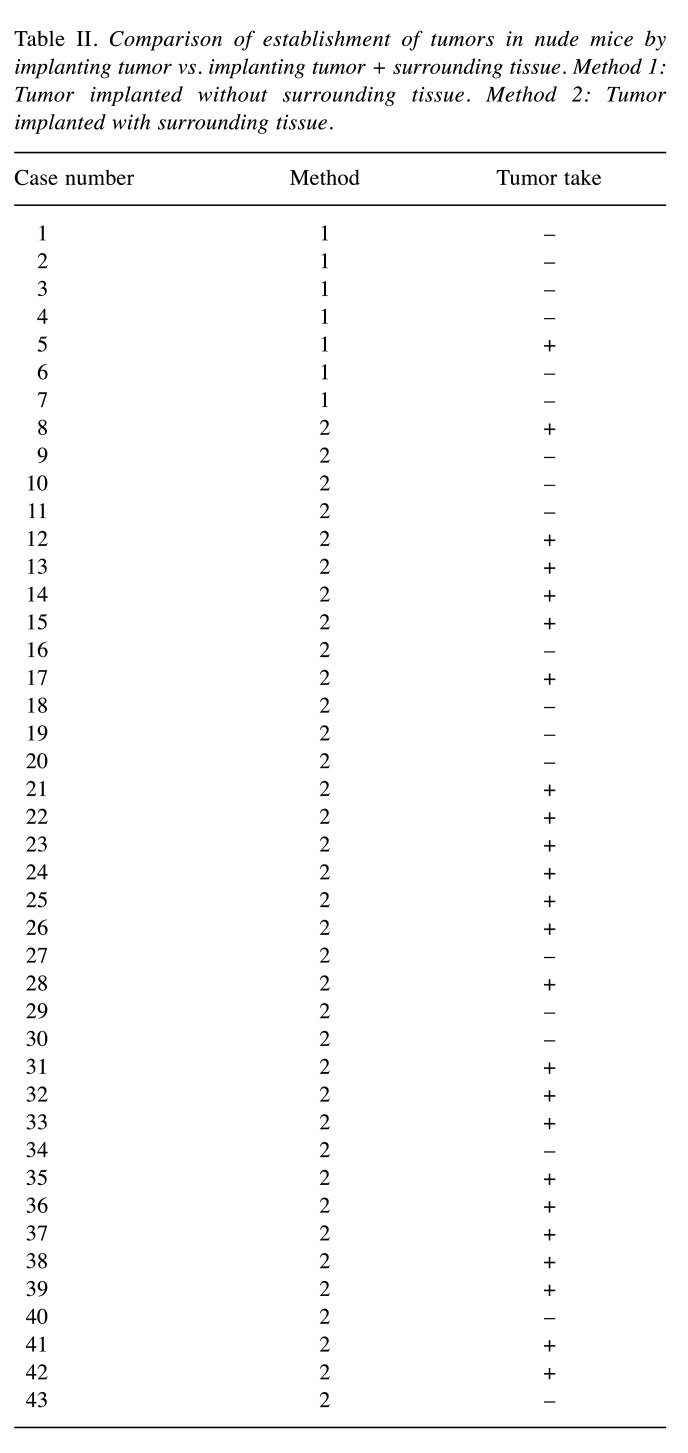

The engraftment success rate improved to 66% (p=0.02) by co-transplanting tumors with surrounding tissues compared to transplanting the tumor only (14%) (Table II). Figure 2 shows a representative growing tumor that was originally co-transplanted with surrounding tissues. Multi-variate logistic regression analysis showed that high stage and metastasis in the patient are positively related to the success of engraftment (p=0.006 and p=0.009 respectively).

Table II. Comparison of establishment of tumors in nude mice by implanting tumor vs. implanting tumor + surrounding tissue. Method 1: Tumor implanted without surrounding tissue. Method 2: Tumor implanted with surrounding tissue.

Figure 2. Representative growing patient-derived tumor co-transplanted with extensive surrounding tissue, four weeks after engraftment was performed. Arrows show the growing tumor.

Discussion

Individualized cancer therapy currently uses genome analysis (5), drug-sensitivity testing with 3-D culture of tumor fragments (6-9) or organoids (10,11) as well as patient-derived xenograft (PDX) or, patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) models (12-16). Genome analysis has helped only a limited number of cancer patients identify effective drugs (17). PDX and PDOX models for patient testing have been limited due to low take rates of patient tumors in nude and other immune-deficient mice and are therefore not widely used for individualized patient therapy.

Therefore, it is important to increase the success rate of patient-tumor establishment in nude or other immune-deficient mice in order to increase their clinical use. In the present study we have shown surrounding tissue co-transplanted with the tumor greatly increases the establishment rate of patient tumors in nude mice. This development should make PDX and PDOX models widely available for cancer patients in the future for individualized cancer therapy.

The potential disadvantage of the co-implantation method is for small tumor specimens, such as from a core-needle biopsy, in which surrounding tissue may not be available. Multi-variate logistic regression analysis showed that high tumor stage and metastasis are positively related to the success of the engraftment.

The future goal is to use the new method of patient-tumor transplantation to enable universal individualized therapy for cancer patients, such that each cancer patient has their own mouse tumor model to help identify improved therapy. The results of the present study show that high tumor stage and the presence of metastasis in the patient increased the probability of tumor engraftment in nude mice, suggesting that the patients in greatest need will have the best chance for identification of more effective therapy with a mouse model of their tumor, especially the PDOX model, which mimics the patient (4,12-16).

Conclusion

Patient-tumor engraftment is significantly increased by co-transplanting tumors and surrounding tissue in nude mice, which gives rise to the possibility of wide-spread use of individualized mouse tumor models for patients, enabling screening for effective drugs for each patient. With the use of highly-immunodeficient mice, such as NOG (18), establishment rates of patient tumors approaching 100% can be expected with the new method of the present report.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contributions

Takuya Murata provided the surgical specimens and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Chihiro Hozumi invented the new co-transplantation method and co-implanted the patient tumors with surrounding tissue in nude mice. Yukihiko Hiroshima implanted some tumors in nude mouse using the standard transplantation method. Koichiro Shimoya, Atsushi Hongo, Sachiko Inubushi and Hirokazu Tanino provided scientific advice for the project. Robert M. Hoffman supervised the study and revised the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported, in part, by a Research Project Grant R01B077 from Kawasaki Medical School. This paper is dedicated to the memory of AR Moossa MD, Sun Lee MD, Professor Li Jiaxi and Masaki Kitajima, MD.

References

- 1.Longo DL. Tumor heterogeneity and personalized medicine. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(10):956–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1200656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, Math M, Larkin J, Endesfelder D, Gronroos E, Martinez P, Matthews N, Stewart A, Tarpey P, Varela I, Phillimore B, Begum S, McDonald NQ, Butler A, Jones D, Raine K, Latimer C, Santos CR, Nohadani M, Eklund AC, Spencer-Dene B, Clark G, Pickering L, Stamp G, Gore M, Szallasi Z, Downward J, Futreal PA, Swanton C. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 366(10):883–892. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rygaard J, Povlsen CO. Heterotransplantation of a human malignant tumour to "Nude" mice. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1969;77(4):758–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1969.tb04520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patient-Derived Mouse Models of Cancer. Patient-Derived Orthotopic Xenografts (PDOX). Hoffman RM (eds.). New York, Humana Press. 2017 doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-57424-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hyman DM, Taylor BS, Baselga J. Implementing genome-driven oncology. Cell. 2017;168(4):584–599. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vescio RA, Redfern CH, Nelson TJ, Ugoretz S, Stern PH, Hoffman RM. In vivo-like drug responses of human tumors growing in three-dimensional gel-supported primary culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1987;84(14):5029–5033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.14.5029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furukawa T, Kubota T, Hoffman RM. Clinical applications of the histoculture drug response assay. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1(3):305–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffman RM, Vescio RA. Development of the histoculture drug response assay (HDRA) Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1760:39–48. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7745-1_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jun E, Park Y, Lee W, Kwon J, Lee S, Kim MB, Lee JS, Song KB, Hwang DW, Lee JH, Hoffman RM, Kim SC. The identification of candidate effective combination regimens for pancreatic cancer using the histoculture drug response assay. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):12004. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-68703-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuveson D, Clevers H. Cancer modeling meets human organoid technology. Science. 2019;364(6444):952–955. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw6985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drost J, Clevers H. Organoids in cancer research. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18(7):407–418. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu XY, Besterman JM, Monosov A, Hoffman RM. Models of human metastatic colon cancer in nude mice orthotopically constructed by using histologically intact patient specimens. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1991;88(20):9345–9349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.9345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murakami T, Murata T, Kawaguchi K, Kiyuna T, Igarashi K, Hwang HK, Hiroshima Y, Hozumi C, Komatsu S, Kikuchi T, Lwin TM, Delong JC, Miyake K, Zhang Y, Tanaka K, Bouvet M, Endo I, Hoffman RM. Cervical cancer patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) is sensitive to cisplatinum and resistant to nab-paclitaxel. Anticancer Res. 2017;37(1):61–65. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.11289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamamoto J, Murata T, Tashiro Y, Higuchi T, Sugisawa N, Nishino H, Inubushi S, Sun YU, Lim H, Miyake K, Hongo A, Nomura T, Saitoh W, Moriya T, Tanino H, Hozumi C, Bouvet M, Singh SR, Endo I, Hoffman RM. A triple-negative matrix-producing breast carcinoma patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) mouse model is sensitive to bevacizumab and vinorelbine, regressed by eribulin and resistant to olaparib. Anticancer Res. 2020;40(5):2509–2514. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.14221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Igarashi K, Kawaguchi K, Murakami T, Miyake K, Kiyuna T, Miyake M, Hiroshima Y, Higuchi T, Oshiro H, Nelson SD, Dry SM, Li Y, Yamamoto N, Hayashi K, Kimura H, Miwa S, Singh SR, Tsuchiya H, Hoffman RM. Patient-derived orthotopic xenograft models of sarcoma. Cancer Lett. 2020;469:332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffman RM. Patient-derived orthotopic xenografts: better mimic of metastasis than subcutaneous xenografts. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(8):451–452. doi: 10.1038/nrc3972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peterson JF, Roden DM, Orlando LA, Ramirez AH, Mensah GA, Williams MS. Building evidence and measuring clinical outcomes for genomic medicine. Lancet. 2019;394(10198):604–610. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31278-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito M, Hiramatsu H, Kobayashi K, Suzue K, Kawahata M, Hioki K, Ueyama Y, Koyanagi Y, Sugamura K, Tsuji K, Heike T, Nakahata T. NOD/SCID/gamma(c)(null) mouse: an excellent recipient mouse model for engraftment of human cells. Blood. 2002;100(9):3175–3182. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]