Abstract

Background/Aim: Somatostatinomas (SSomas) constitute a rare neuroendocrine tumor. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the current published literature about pancreatic SSomas and report epidemiologic and clinicopathologic data for this entity. Patients and Methods: A combined automated and manual systematic database search of the literature was performed using electronic search engines (Medline PubMed, Scopus, Ovid and Cochrane Library), until February 2020. Statistical analysis was performed using the R language and environment for statistical computing. Results: Overall, the research revealed a total of 36 pancreatic SSoma cases. Patient mean age was 50.25 years. The most common pancreatic location was the pancreatic head (61.8%). The most frequent clinical symptom was abdominal pain (61.1%). Diagnostic algorithm most often included Computed Tomography and biopsy; surgical resection was performed in 28 cases. Out of the 36 cases, 22 had been diagnosed with a metastatic tumor and metastasectomy was performed in 6 patients with a worse overall survival (OS) (p=0.029). In total, OS was 47.74 months. Conclusion: Patients with metastatic disease did not benefit from metastasectomy, but the sample size was small to reach definite conclusions. However, further studies with longer follow-up are needed for a better evaluation of these results.

Keywords: Somatostatinoma, pancreas, neuroendocrine tumors, diagnosis, therapeutic strategies

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) derive from multipotent cells that are located throughout the entire gastrointestinal (GI) tract, they belong to the diffuse endocrine system and have the ability to secret peptides. The majority of NETs are non-functional and detected in imaging studies as incidentalomas; however, a functional group which is related with various endocrine syndromes has been described (1). Among these, somatostatinoma (SSoma) constitutes an extremely rare tumor, representing 4% of NETs with an estimated incidence of 1/40,000,000 individuals per year in the general population. It is located in the pancreas or the GI tract, while 60% of cases originate in the ampulla and periampullary region (2,3). Malignancy is encountered in 60-70% of affected cases and pancreatic SSomas present with higher malignancy rates in comparison to duodenal lesions (4). Moreover, SSomas are often found in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1) or von Hippel-Lindau syndrome (vHL), whereas only a few cases are associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1; von Recklinghausen’s disease) (5-7). Usually, patients do not present with an associated clinical syndrome and 67% of them appear with metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis (8). However, overproduction of somatostatin leads to the typical SSoma syndrome, which consists of diabetes mellitus (DM), steatorrhea and diarrhea, cholelithiasis, weight loss, hypochlorhydria and achlorhydria and is apparent in less than 10% of patients (9,10).

Patients with a non-functioning SSoma can be completely asymptomatic or experience symptoms related to the tumor mass effect, the metastases or the invasion of contiguous structures (1,8). Therefore, the tumors are detected by Computed Τomography (CT), Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or, on occasion, Somatostatin Receptor Scintigraphy (SRS) and Endoscopic Ultrasonography (EUS) (1,11,12). Management of SSomas includes treatment of the excess somatostatin production, surgical interventions and adjuvant therapy when needed (11,13-15). The purpose of this study was to evaluate the published literature about pancreatic SSomasand and report on epidemiologic and clinicopathologic data for this rare entity. Biological behavior of SSomas as well as available treatment modalities, are also analyzed.

Patients and Methods

A combined automated and manual systematic database search of the relevant medical literature was performed using electronic search engines (Medline, PubMed, Scopus, Ovid and Cochrane Library), until February, 1st, 2020. Publications of interest included randomized and non-randomized studies, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, case series, case reports, letters to the editor and conference abstracts. Nevertheless, only data extracted from case reports or series were available for use with the pooled analysis. Search criteria initiated for PubMed were: (somatostatinoma OR (neuroendocrine [Title] AND (tumour [Title] OR tumor[Title] OR tumours [Title] OR tumors[Title]))) AND (“case report” OR “case series” OR “trial” OR “case-control” OR “Case Reports”[pt] OR study OR review OR meta-analysis OR letter OR conference) For other databases: (somatostatinoma OR (neuroendocrine AND (tumour OR tumor OR tumours OR tumors))) were used.

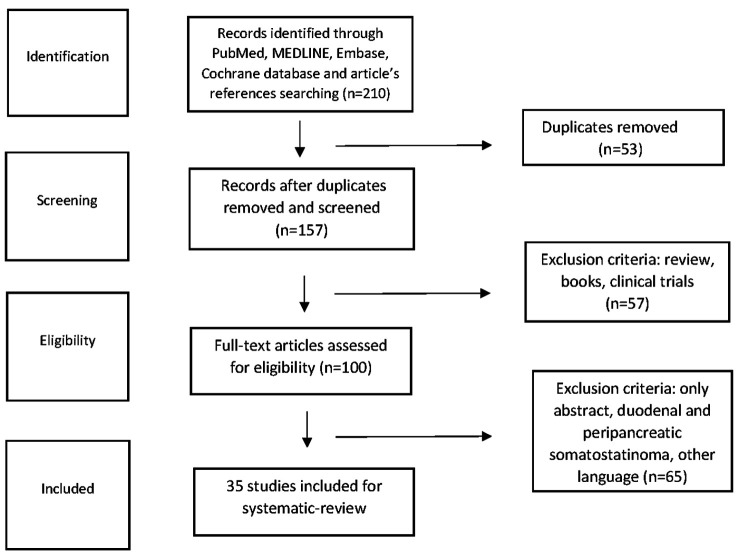

We identified all studies that reported on surgical or conservative management of SSoma tumor patients. Papers not written in English as well as cases of SSomas located in periampullary region or duodenum were excluded from our survey (Figure 1). Data extracted from eligible studies included tumor patient characteristics such as age, sex, associated diseases, clinical symptoms on presentation, diagnostic approach, tumor size, stage and location, surgical intervention type, adjuvant therapy details, tumor recurrence information, and survival (overall and disease-free) outcomes.

Figure 1. Flow diagram depicting all included surveys with regard to pancreatic SSoma cases or case series.

Statistical analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using the R language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, http://www.R-project.org). For continuous variables, Shapiro-wilk test for normality was used, and univariate analysis was performed using t-test or the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test as appropriate. Categorical variables were examined using chi-square test. Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank test was used for statistical comparisons. Multivariate comparisons were performed using cox proportional hazards models.

Results

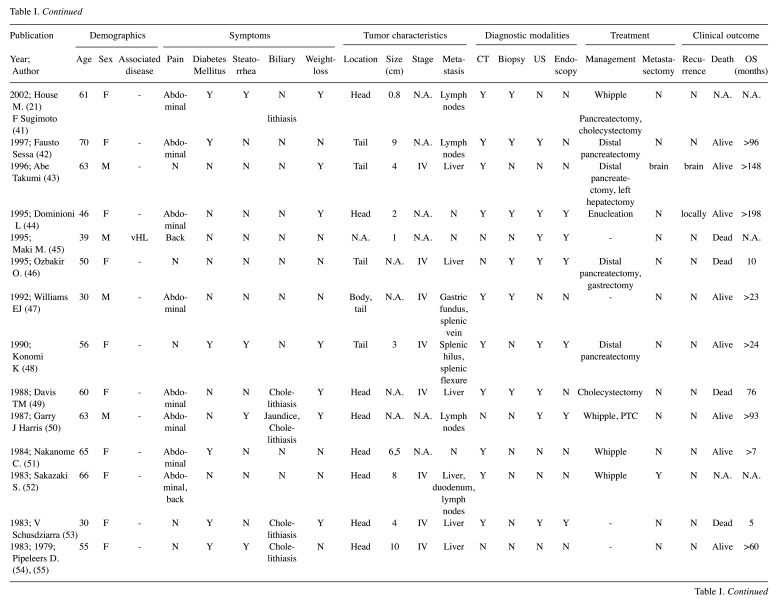

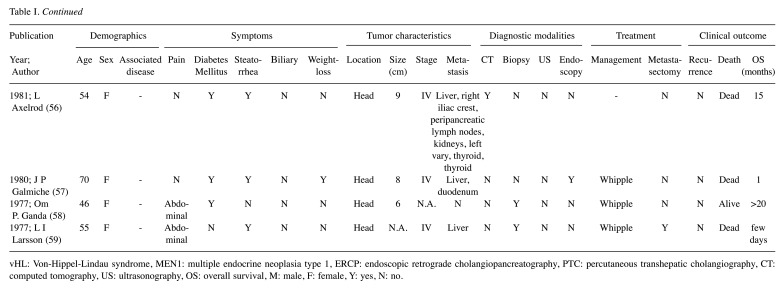

The literature search revealed 36 SSoma cases during the period from January 1977 to February 2020. Eligible articles were 36, among which one paper involved two separate cases, while two other case reports were merged as a recurrence of the same patient 16 years after resection, resulting in 36 unique cases (Table I) (4,6,9,21,28-59). Patients’ mean age was 50.25±14.39 years with a female predominance of 2:1 (24 females vs. 12 males). It is worth noting that 44.4% of cases referred to patients younger than 50 years old, while 38.9% of patients were between 50 and 64 years old. Patients older than 65 years were only 16.7% of the cases. Two patients were diagnosed with MEN1, one with Neurofibromatosis 1 (von Recklinghausen’s disease or NF1) and one with vHL syndrome.

Table I. Modified geriatric assessment domains and tools.

vHL: Von-Hippel-Lindau syndrome, MEN1: multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, PTC: percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography, CT: computed tomography, US: ultrasonography, OS: overall survival, M: male, F: female, Y: yes, N: no

Tumor characteristics analyzed in our study include pancreatic location, size, stage, metastasis and possible recurrence. The predominant pancreatic location was the pancreatic head (21 cases, 61.8%), followed by pancreatic tail (13 cases, 38.2%) and body involvement (6 cases, 17.6%) with minor overlap (11.1%). Mean tumor size was 5.21±3.26 cm. Tumor stage was markedly under-reported (55.5%), with 18 patient tumors categorized as Stage IV (90%) and only two as Stage II (10%). Out of the 36 cases, 18 had been diagnosed with a metastatic tumor (50% of total), the majority of which included a liver metastasis. Overall, possible tumor recurrences were not reported (91.7%), mainly due to the nature of the publications which did not include any cohort or trial that methodologically perform rigorous follow-up. The three reported cases of recurrence included local recurrence, liver and brain metastases.

The most common clinical symptom on admission was pain, mainly located in the abdomen (22 patients, 61.1%), while 3 patients (8.3%) presented with back pain and only 1 patient (2.8%) complained of chest pain. Other common symptoms included steatorrhea (41.7%), weight-loss (38.9%) and new onset of diabetes mellitus (DM) (33.3%). Moreover, four patients presented with jaundice (11.1%) and 7 reported cholelithiasis (19.4%); one patient (2.8%) diagnosed with MEN1 syndrome reported bilateral galactorrhoea. Diagnostic approach most often included CT (29 cases, 80.6%), biopsy (20 cases, 55.6%), ultrasonography (US) (16 cases, 44.4%), endoscopy (11 cases, 30.6%) and other methods. Surgical resection was performed in 28 cases (77.8%), 14 of which underwent Whipple’s pancreatoduodenectomy (50%), 10 distal pancreatectomy (35.7%), two cases were submitted to tumor enucleation (7.1%) and two underwent other surgical interventions (7.1%). Metastases were evident in 18 patients at the time of diagnosis (50%) while metastasectomy was performed in 6 of them (33.3%). Regarding adjuvant therapy, streptozocin was given in 9 cases, 5-FU in 4 cases and mitomycin-c in 3 cases. Additionally, there was 1 patient that was administered 111-ln octreotide. Eleven deaths were reported among the patients (36.7%) with a mean survival of 47.7 months (0.1-240 months).

Statistical analysis. In addition to the systematic review, a statistical analysis was performed. The analysis was limited by the nature of the publications which did not include any cohort or trial that evaluated patients at regular intervals for a long-term assessment. Therefore, individual data was pooled from the available case studies. Univariate analysis of the independent variables (Table II) did not reveal any significant predictors for death, apart from a significantly worse survival in metastasectomized patients (p=0.029). Multivariate analysis adjusting for age, sex and tumor size confirmed the same results (p=0.049, HR=14.5, 95% CI=1.01-207) (Table III).

Table II. Descriptive statistics in pancreatic somatostatinoma.

CT: Computerized tomography, US: ultrasonography

Table III. Univariate predictors of death in pancreatic somatostatinoma patients.

HR: Hazard Ratio, LCI: lower confidence interval (95%), HCI: higher confidence interval (95%)

Discussion

NETs derive from multipotent cells that are located throughout the entire GI tract. Even though the majority of NETS are non-functional, there is a functional group which is related with various endocrine syndromes due to the ability to secret peptides (1). SSomas represent 4% of NETs with an estimated incidence of 1/40,000,000 individuals per year in the general population (3). These tumors are the result of overproduction of somatostatin, which is a cyclic peptide of 14 amino acids secreted from delta cells of the pancreas under normal conditions. SSomas can be detected in both the pancreas and the GI tract (8,9). Previous studies estimated that NETs’ incidence is higher among older age groups with a significant rise during the last decades (16). However, in contrast to those data, our analysis revealed a tendency of pancreatic SSoma towards younger ages. Patient mean age was 50.25 years, ranging from 22 to 72 with a female predominance of 2:1. Our research indicated that SSomas were least common among older ages, while 44.4% of patients were younger than 50 years. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that analyzes all the reported cases of pancreatic SSomas since the first one, described in 1977.

These tumors are mainly silent and diagnosed incidentally or present with vague, non-specific symptoms that make the diagnosis challenging (17). However, somatostatin inhibits insulin, glucagon, cholecystokinin and gastrin, so many symptoms can occur through those mechanisms of action. Consequently, SSomas, when functional, typically present with cholelithiasis, weight loss, diarrhea, steatorrhoea and anemia. Furthermore, some patients also present with diabetes mellitus (DM) (9). According to our data, the most common clinical symptom on admission was abdominal pain. Other frequent symptoms or signs included steatorrhoea, weight-loss and new onset of DM. Consequently, in case these symptoms are present in a patient, SSomas should be included in the differential diagnosis. Interestingly, 3 patients experienced severe back pain and 1 patient documented chest pain, which could complicate and challenge the differential diagnosis. Moreover, 4 patients presented with jaundice, probably due to the obstruction of the biliary tract; galactorrhoea appeared to be a rare symptom mostly among patients diagnosed with MEN 1 syndrome. Our analysis also revealed that pancreatic head was the predominant pancreatic location, a result that agrees with the current literature.

Official diagnosis requires measuring fasting plasma somatostatin hormone concentration, which should be 3 times over the normal limits for diagnosis (4). In case of an indeterminate test result, stimulatory examinations such as secretin or calcium stimulation tests can be used. Other modalities that may contribute to the diagnostic procedure are CT or MRI as well as EUS and SRS (11,12). SRS leads to localization of the disease and possible metastases, but cannot provide data about the tumor size and its invasive potential. EUS on the other hand, is the best option in locating tumors at the head of pancreas and can obtain biopsies via fine-needle aspiration (11). Generally, though, pathological examination after surgery or biopsy provides the definitive diagnosis (18,19). According to our study, the majority of cases relied on CT for diagnosis. Other common diagnostic means utilized were endoscopy and EUS-guided biopsy. MRI, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) and fluorodeoxyglucose PET-SCAN (FDG-PET) were also proposed in few cases. Strangely enough, SRS was not popular among patients, as there was no reported case in which it constituted a mean of diagnosis.

Management of SSomas includes an attempt for relief of symptoms combined with surgical interventions and targeted adjuvant therapy (11). Regarding small tumors (less than 2 cm), surgery is the best treatment option. Nonetheless, 70-92% of patients present with advanced disease and extensive metastases, for which systemic therapy is implemented. Tumors with a size of more than 2 cm in the head of pancreas or smaller tumors with lymph node metastases will mandate a Whipple’s pancreaticoduodenectomy (20). Tumors at the body or tail of the pancreas are either enucleated (<2 cm) or removed by distal pancreatectomy (13). In our study, 18 out of 36 patients presented without metastases or locally advanced disease. With the exception of one patient that died before being operated, due to comorbidities, the remaining 17 were managed with either enucleation or with a more extensive surgery such as Whipple’s procedure or distal pancreatectomy.

Regarding patients with metastatic disease, except for systemic adjuvant therapy, more treatment options are taken into consideration (13,21). In our study, 18 out of 36 patients presented with hematogenous metastatic lesions at the time of diagnosis. Out of 14 patients that presented with liver metastases, 1 case was managed with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, 1 with radiofrequency ablation and chemoembolization and another 1 with ablation and cryotherapy. Metastasectomy was performed in a total of 6 patients, among the 18 cases that had been diagnosed with metastatic foci. Metastasectomy was the only factor that predisposed to higher risk of death (HR=14.5, 95% CI=1.01-207), even after adjusting for patient age, sex, and tumor size. That could be attributed to higher perioperative mortality, worse patient’s performance status among those who were submitted to metastasectomy, or other comorbidities that were not reported. Further studies with longer follow-up, better documentation of tumor staging, patient comorbidities and performance status should be designed, so as to better take those covariates into account and reach more accurate conclusions.

In general, SSomas’ biological behavior and prognosis are less aggressive than carcinomas, but they appear to metastasize to distant organs. This observation can be explained by the classical ‘anatomical’ hypothesis, according to which primary NETs are usually drained by the portal venous system. As a result, liver involvement is a common finding and often defines SSomas’ metastatic pattern. However, the treatment strategy is challenging and difficult to be established due to the rarity of liver metastases. A recent large review on surgical management of neuroendocrine liver metastases demonstrated similar outcomes and encouraged hepatectomy when technically feasible (22). Similar results were also presented in a review of 116 studies, which recommended metastasectomy as the potentially curative therapeutic option for patients with metastatic NET if technically feasible (23). Although these results need to be further evaluated in order to reach definite conclusions, metastasectomy seems to ameliorate symptoms caused by the excess hormonal secretion. Surgical debulking of liver metastases might alleviate the symptoms of diarrhea and steatorrhea as well (24).

Systemic therapy in patients with SSomas at an advanced stage includes somatostatin analogues for symptom relief, molecular targeted therapy (e.g., everolimus, sunitinib), and adjuvant chemotherapy (25,26). Somatostatin analogues include octreotide-LAR and lanreotide-autogel, but only in few cases has their use been successful (12,15). Interferon-alpha can also be used alone or in combination with octreotide to control symptoms in patients’ refractory to octreotide (27). 5-FU, doxorubicin and streptozocin are chemotherapy agents that were proposed in the treatment of SSoma patients with mediocre results (15). Unfortunately, in our study there were limited data as far as adjuvant therapy is concerned. The most common chemotherapy agents used in these cases were streptozocin, 5-FU and mitomycin-c. Additionally, there was 1 patient that was administered 111-ln octreotide. Overall, the five-year survival rate for patients with pancreatic SSomas is 60-100% with localized lesions or 15-60% with metastatic disease (2,9). Poor prognostic factors include large size (>3 cm), poor differentiation and positive lymph nodes. Non-functioning, poorly differentiated tumors are usually more common and have a worse prognosis than functioning ones (9). According to our study, 11 patients died during follow-up (36.7%) and the overall survival was 47.7 months.

Our systematic review summarizes the available clinical evidence in the field of pancreatic SSomas. However, it has certain limitations including heterogeneity in patient’s selection and a possible selective reporting bias as obviously not all cases are routinely reported. In addition, all included articles are retrospective case reports; therefore, the studies’ design as well as the postoperative management approach was different among surgical centers. Moreover, the total number of cases included in this study is relatively small and regional differences are apparent.

Conclusion

Pancreatic SSomas constitute a rare entity that needs to be further evaluated. The most common clinical symptoms appeared to be pain, diabetes mellitus, steatorrhea and weight loss. Regarding diagnostic algorithm, measuring fasting plasma hormone concentration, biopsy and CT are mainly required. Management of SSomas includes surgery, adjuvant therapy and relief of symptoms. For patients with advanced disease, our results indicated that metastasectomy did not provide a benefit in overall survival. However, data extracted from our survey were limited by the nature of included publications. Thus, further studies with longer follow-up and better study design are needed for better elucidation of these results.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist.

Authors’ Contributions

Aikaterini Mastoraki, Dimitrios Schizas, Eleni Papoutsi and Vasiliki Ntella designed the study; Prodromos Kanavidis, Athanasios Sioulas, Marina Tsoli, Georgios Charalampopoulos and Michail Vailas collected relevant clinical data; Aikaterini Mastoraki, Dimitrios Schizas and Evangelos Felekouras analyzed the data and wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Anderson CW, Bennett JJ. Clinical presentation and diagnosis of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2016;25(2):363–374. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kloppel G, Anlauf M. Epidemiology, tumor biology and histopathological classification of neuroendocrine tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19(4):507–517. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zamir MA, Hakim W, Yusuf S, Thomas R. Imaging of pancreatic-neuroendocrine tumors: an outline of conventional radiological techniques. Curr Radiopharm. 2019;12(2):135–155. doi: 10.2174/1874471012666190214165845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nesi G, Marcucci T, Rubio CA, Brandi ML, Tonelli F. Somatostatinoma: clinico-pathological features of three cases and literature reviewed. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:521–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garbrecht N, Anlauf M, Schmitt A, Henopp T, Sipos B, Raffel A, Eisenberger CF, Knoefel WT, Pavel M, Fottner C, Musholt TJ, Rinke A, Arnold R, Berndt U, Plöckinger U, Wiedenmann B, Moch H, Heitz PU, Komminoth P, Perren A, Klöppel G. Somatostatin-producing neuroendocrine tumors of the duodenum and pancreas: incidence, types, biological behavior, association with inherited syndromes, and functional activity. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15:229–241. doi: 10.1677/ERC-07-0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takai A, Setoyama T, Miyamoto S. Pancreatic somatostatinoma with von Recklinghausen’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:A28. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jensen RT, Berna MJ, Bingham DB, Norton JA. Inherited pancreatic endocrine tumor syndromes: advances in molecular pathogenesis, diagnosis, management, and controversies. Cancer. 2008;113:1807–1843. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parbhu SK, Adler DG. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: contemporary diagnosis and management. Hospital Practice (1995) 2016;44(3):109–119. doi: 10.1080/21548331.2016.1210474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williamson JML, Thorn CC, Spalding D, Williamson RC. Pancreatic and peripancreatic somatostatinomas. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2011;93(5):356–360. doi: 10.1308/003588411X582681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dinesh U, Pervatikar SK, Rao R. FNAC diagnosis of pancreatic somatostatinoma. J Cytol. 2009;26(4):153–155. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.62187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellison TA, Edil BH. The current management of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Adv Surg. 2012;46(1):283–296. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito T, Igarashi H, Jensen RT. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: Clinical features, diagnosis and medical treatment: Advances. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26(6):737–753. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azimuddin K, Chamberlain RS. The surgical management of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Surg Clin North Am. 2001;81(3):511–525. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johns Hopkins Medicine, The Sol Goldman Pancreatic Cancer Research Center. Islet cell tumors of the pancreas/endocrine neoplasms of the pancreas. Available at: http://pathology.jhu.edu/pancreas/news2018.php. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Metz DC, Jensen RT. Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors: pancreatic endocrine tumors. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1469–1492. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dasari A, Shen C, Halperin D, Zhao B, Zhou S, Xu Y, Shih T, Yao JC. Trends in the incidence, prevalence, and survival outcomes in patients with neuroendocrine tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1335–1342. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zakaria A, Hammad N, Vakhariya C, Raphael M. Somatostatinoma presented as double-duct sign. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2019;2019:9506405. doi: 10.1155/2019/9506405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farr CM, Price HM, Bezmalinovic Z. Duodenal somatostatinoma with congenital pseudoarthrosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1991;13(2):195–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roy J, Pompilio M, Samama G. Pancreatic somatostatinoma and MEN 1. Apropos of a case. Review of the literature. Ann Endocrinol. 1996;57(1):71–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.House MG, Yeo CJ, Schulick RD. Periampullary pancreatic somatostatinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9(9):869–874. doi: 10.1007/BF02557523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moug SJ, Leen EHorgan PG, Imrie CW. Radiofrequency ablation has a valuable therapeutic role in metastatic VIPoma. Pancreatology. 2006;6(1-2):155–159. doi: 10.1159/000090257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fung AKY, Chong CCN. Surgical strategy for neuroendocrine liver metastases. Surgical Practice. 2019;23(2):59–67. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nigri G, Petrucciani N, Debs T, Mangogna LM, Crovetto A, Moschetta G, Persechino R, Aurello P, Ramacciato G. Treatment options for PNET liver metastases: A systematic review. World J Surg Oncol. 2018;16(1):142. doi: 10.1186/s12957-018-1446-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mansour JC, Chen H. Pancreatic endocrine tumors. J Surg Res. 2004;120:139–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caplin ME, Pavel M, Ćwikła JB, Phan AT, Raderer M, Sedláčková E, Cadiot G, Wolin EM, Capdevila J, Wall L, Rindi G, Langley A, Martinez S, Blumberg J, Ruszniewski P, CLARINET Investigators Lanreotide in metastatic enteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. NEJM. 2014;371(3):224–233. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1316158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rinke A, Wittenberg M, Schade-Brittinger C, Aminossadati B, Ronicke E, Gress TM, Müller HH, Arnold R, PROMID Study Group. Placebo controlled, double blind, prospective, randomized study on the effect of octreotide lar in the control of tumor growth in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine midgut tumors (PROMID): results on long term survival. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;104(1):26–32. doi: 10.1159/000443612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vinik AI, Raymond E. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: approach to treatment with focus on sunitinib. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2013;6(5):396–411. doi: 10.1177/1756283X13493878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kilambi R, Singh AN, Das P, Madhusudhan KS, Pal S. Somatostatinoma masquerading as chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2018;47:e19–e20. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mori Y, Sato N, Taniguchi R, Tamura T, Minagawa N, Shibao K, Higure A, Nakamoto M, Taguchi M, Yamaguchi K. Pancreatic somatostatinoma diagnosed preoperatively: report of a case. JOP. 2014;15:66–71. doi: 10.6092/1590-8577/1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varsavsky M, Reyes-García R, Alonso García G, Muñoz-Torres M. An unusual association of neuroendocrine tumors in MEN 1A. Pituitary. 2012;15(3):393–397. doi: 10.1007/s11102-011-0334-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Do Cao C, Mekinian A, Ladsous M, Aubert S, D’Herbomez M, Pattou F, Bourdelle-Hego MF, Wémeau JL. Hypercalcitonemia revealing a somatostatinoma. Ann Endocrinol. 2010;71:553–557. doi: 10.1016/j.ando.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arima H, Natsugoe S, Maemura K, Hata Y, Kumanohoso T, Imamura H, Mataki Y, Kurahara H, Shinchi H, Takao S, Aikou T. Asymptomatic somatostatinoma of the pancreatic head: Report of a case. Surg Today. 2010;40:569–573. doi: 10.1007/s00595-008-4089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang B, Xie QP, Gao SL, Fu YB, Wu YL. Pancreatic somatostatinoma with obscure inhibitory syndrome and mixed pathological pattern. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2010;11:22–26. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B0900166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dinesh U, Pervatikar S, Rao R. FNAC diagnosis of pancreatic somatostatinoma. J Cytol. 2009;26:153–155. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.62187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu RS, Chen Y, Wang LH, Xu XF, Jiang DY. A large functional somatostatinoma in the pancreatic tail: Atypical CT appearances. Turkish J Gastroenterol. 2009;20:291–294. doi: 10.4318/tjg.2009.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He X, Wang J, Wu X, Kang L, Lan P. Pancreatic somatostatinoma manifested as severe hypoglycemia. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2009;18:221–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Čolović RB, Matić SV, Micev MT, Grubor NM, Atkinson HD, Latincić SM. Two synchronous somatostatinomas of the duodenum and pancreatic head in one patient. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(46):5859–5863. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suzuki H, Kuwano H, Masuda N, Hashimoto S, Kanoh K, Nomoto K, Shimura T, Katoh H. Diagnostic usefulness of FDG-PET for malignant somatostatinoma of the pancreas. Hepatogastroenterology. 2018;55:1242–1245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marakis G, Ballas K, Rafailidis S, Alatsakis M, Patsiaoura K, Sakadamis A. Somatostatin-producing pancreatic endocrine carcinoma presented as relapsing cholangitis - A case report. Pancreatology. 2005;5:295–299. doi: 10.1159/000085286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin FC, Lin CM, Hsieh CC, Li WY, Wang LS. Atypical thymic carcinoid and malignant somatostatinoma in type I multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome. Am J Clin Oncol. 2003;26:270–272. doi: 10.1097/01.COC.0000020584.56294.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugimoto F, Sekiya T, Saito M, Iiai T, Suda K, Nozawa A, Nakazawa T, Ishizaki T, Ikarashi T. Calcitonin-producing pancreatic somatostatinoma: report of a case. Surg Today. 1998;28:1279–1282. doi: 10.1007/BF02482815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sessa F, Arcidiaco M, Valenti L, Solcia M, Di Maggio E, Solcia E. Metastatic psammomatous somatostatinoma of the pancreas causing severe ketoacidotic diabetes cured by surgery. Endocr Pathol. 1997;8(4):327–333. doi: 10.1007/BF02739935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abe T, Oshida K, Matsumoto K, Iida M, Sanno N. Brain metastasis from malignant pancreatic somatostatinoma. J Neurosurg. 1996;85(4):681–684. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.85.4.0681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dominioni L, Dionigi R, Benevento A, Capella C, La Rosa S, Roncari G, Garancini S. Very late recurrence of a somatostatin cell tumor of the head of the pancreas. Pancreas. 1995;10(4):417–419. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199505000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maki M, Kaneko Y, Ohta Y, Nakamura T, Machinami R, Kurokawa K. Somatostatinoma of the pancreas associated with von Hippel-Lindau disease. Intern Med. 1995;34(7):661–665. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.34.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ozbakir O, Keleştimur F, Oztürk F, Sözüer E, Unal A, Patiroğlu TE, Güven K. Carcinoid syndrome due to a malignant somatostatinoma. Postgrad Med J. 1995;71(841):695–698. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.71.841.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams EJ, Ratcliffe WA, Stavri GT, Stamatakis JD. Hypercalcaemia secondary to secretion of parathyroid hormone related protein from a somatostatinoma of the pancreas. Ann Clin Biochem. 1992;29(3):354–357. doi: 10.1177/000456329202900321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Konomi K, Chijiiwa K, Katsuta T, Yamaguchi K. Pancreatic somatostatinoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. 1990;43(4):259–265. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930430414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davis TM, Bray G, Domin J, Bloom SR. A case of somatostatinoma: responses to food and SMS 201-995 administration. Pancreas. 1988;3(6):729–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harris GJ, Tio F, Cruz AB. Somatostatinoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. 1987;36(1):8–16. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930360104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nakanome C, Koizumi M, Fujiya H, Akai H, Toyota T, Goto Y, Kameyama J, Miyakawa K, Hanew K. Somatostatinoma syndrome accompanied by overproduction of pancreatic polypeptide. Tohoku J exp Med. 1984;142(2):201–210. doi: 10.1620/tjem.142.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sakazaki S, Umeyama K, Nakagawa H, Hashimoto H, Kamino K, Mitsuhashi T, Yamaguchi K. Pancreatic somatostatinoma. Am J Surg. 1983;146(5):674–679. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(83)90310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schusdziarra V, Grube D, Seifert H, Galle J, Etzrodt H, Beischer W, Haferkamp O, Pfeiffer EF. Somatostatinoma syndrome. Clinical, morphological and metabolic features and therapeutic aspects. Klin Wochenschr. 1983;61(14):681–689. doi: 10.1007/BF01487613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pipeleers D, Couturier E, Gepts W, Reynders J, Somers G. Five cases of somatostatinoma: Clinical heterogeneity and diagnostic usefulness of basal and tolbutamide-induced hypersomatostatinemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;56(6):1236–1242. doi: 10.1210/jcem-56-6-1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pipeleers D, Somers G, Gepts W, De Nutte N, De Vroede M. Plasma pancreatic hormone levels in a case of somatostatinoma: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1979;49(4):572–579. doi: 10.1210/jcem-49-4-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Axelrod L, Bush MA, Hirsch HJ, Loo SW. Malignant somatostatinoma: clinical features and metabolic studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1981;52(5):886–896. doi: 10.1210/jcem-52-5-886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Galmiche JP, Chayvialle JA, Dubois PM, David L, Descos F, Paulin C, Ducastelle T, Colin R, Geffroy Y. Calcitonin-producing pancreatic somatostatinoma. Gastroenterology. 1980;78(6):1577–1583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ganda OP, Weir GC, Soeldner JS, Legg MA, Chick WL, Patel YC, Ebeid AM, Gabbay KH, Reichlin S. Somatostatinoma: a somatostatin-containing tumor of the endocrine pancreas. N Engl J Med. 1977;296(17):963–967. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197704282961703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Larsson LI, Holst JJ, Kühl C, Ingemansson S, Kühl C, Jensen SL, Lundqvist G, Rehfeld JF, Schwartz TW. Pancreatic somatostatinoma. Clinical features and physiological implications. Lancet. 1977;309(8013):666–668. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)92113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]