Abstract

Aim: Follow-up strategies for primary extremity soft-tissue sarcomas (eSTS) in adults were evaluated in a systematic review of the published literature. Material and Methods: The published literature was reviewed using PubMed. Of 136,646 studies published between 1985 and 2019, 78 original articles met the inclusion criteria. Articles were selected on the basis of the PRISMA guidelines. The selected articles were then cross-searched to identify further publications. August 1, 2019 was used as the concluding date of publication. Results: A variety of follow-up schedules have been reported in recently published literature. Two official guidelines have been approved by international societies. The guidelines distinguish between high- and low-grade STS, but mention a wide range of follow-up intervals. Established tools of follow-up include computed tomograph, X-rays of the chest, and magnetic resonance imaging of the primary tumor site in addition to clinical observation and physical examination. Conclusion: Further research will be needed to establish evidence-based guidelines and schedules for follow-up strategies in patients with eSTS.

Keywords: Follow up, systematic review, malignant tumor, soft tissue sarcoma

Soft-tissue sarcomas (STS) of the extremities constitute less than 1% of all malignant tumors (1-4). Patients with high-grade STS are at risk of developing local recurrence (LR) and distant metastases (DM) after having undergone successful surgical resection of the primary tumor (5-10). Rates of STS differ in terms of size, grade, and subtype (5,11). According to the published literature, 12,750 new cases of STS and 5,270 deaths occurred in the United States, resulting in a mortality rate of about 40% in 2019 (12-14). Recent published studies have revealed a yearly incidence of about 4-5/100,000 in Europe; liposarcoma and leiomyosarcoma are the most common histological subtypes (15-17). Nearly every third patient with primarily local STS will develop DM during the follow-up period, most likely in the lungs (18).

The large majority of STS are primarily located in the extremities; about 40% occur in the lower limbs (1,2,19-30). The second most frequent location is the abdomen (retroperitoneal or visceral); the lesions are usually very voluminous at the time of presentation (1,19-23). More than 75% of malignant STS are located beneath the fascia (20,22,23,27). The median age of patients at the initial diagnosis of primary STS is around 50 years and a slight preponderance of the male gender has been reported (1,4,21,22,25,26,28,30,31).

STS are divided into more than 50 histological subtypes, arising from mesodermal or neuroectodermal tissue (15,19,32). The histological classification is based on the differentiation of tumor cells, regardless of their origin (33). The European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) (21,34), as well as Brennan and co-workers (21,34) have identified more than 80 histological entities that may be further subdivided into even greater numbers of subsets. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) makes a rough division of STS into those of the extremity (eSTS), the superficial trunk or head and neck, the retroperitoneum, the abdomen, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, desmoid tumors (aggressive fibromatosis), and rhabdomyosarcoma (35). The most prevalent histological subtype has proven to be liposarcoma, followed by leiomyosarcoma (20-22,27,28,36).

The treatment is primarily decided on the basis of tumor stage, grade, location, and the individual features of the patient. Wide excision with negative margins is the gold standard for localized eSTS. According to the American Joint Committee on Cancer, adjuvant radiotherapy was shown to be beneficial in patients with high-grade lesions, lesions in deep location or large entities (>5 cm) (37). If negative margins are not achieved at the first attempt, the surgeon is well advised to perform revision surgery with wide excision if possible (34). Radical resection, which is defined as the excision of the entire anatomical compartment including the tumor, can also be performed in some cases. However, this approach impairs the patient’s quality of life and should be avoided if medically justified (38). The extent of treatment in advanced or metastatic disease is a more complex issue and must be decided on an individual basis. Surgery remains the standard approach for lung metastases without extrapulmonary spread, provided all lesions (local and metastatic) can be excised completely even if the patient has several metastases (24,39). Chemotherapy might be added in selected cases, although its influence on survival remains to be proven, while for extrapulmonary disease it constitutes adjuvant treatment. For localized but clinically unresectable STS, the ESMO guidelines state that chemotherapy or radiotherapy should be administered either individually or in combination. The patient should be evaluated for surgery again after the treatment (34).

As regards imaging studies during follow-up, computed tomographic (CT) scans, X-rays of the chest, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of tumor sites are established procedures for STS (34). According to the published literature, ultrasonography or CT scans of the abdomen are not performed consistently, although STS is associated with metastases in virtually any region of the body, including the brain, bones, the abdomen, and the retroperitoneum (34). As these metastases are reported to be rare occurrences, a diagnostic MRI of the brain or CT scans of the abdomen are only performed when the patients are symptomatic (40). Thus, there is a lack of any consensus on the reasons for, or frequency of, follow-up examinations in patients with STS (5,34). In addition, the overall duration of follow-up and the most suitable imaging procedures are not conclusively established. The same applies to whether follow-up investigations should be conducted at specialized sarcoma centers.

Although diagnostic equipment and algorithms, interdisciplinary sarcoma boards (oncologists, radiologists, surgeons, pathologists etc.), and treatment modalities have improved markedly over time, the follow-up regimen for eSTS has not changed for decades (40). In the present report, we summarize the evidence on follow-up strategies after primary treatment of extremity STS in adult patients in terms of the frequency and duration of follow-up investigations, and the most suitable imaging procedures.

Materials and Methods

Studies published between January 1, 1985 and July 31, 2019 were included in a systematic review. In view of the fact that eSTS are rare malignancies, we considered eligible retrospective studies, case series, retrospective cohort studies, as well as individual case reports. The primary database used for the search was PubMed. As suggested in previous studies, further publications were identified by cross-searching the article references. Thus, a backward and forward citation search was performed. The concluding search date for the review was August 1, 2019. PubMed was searched using the following terms: STS OR soft tissue sarcoma* OR sarcoma* OR soft-tissue-sarcoma* AND follow-up OR follow up OR followup OR surveillance OR aftertreatment. The review was structured in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (41). Independently of each other, three Authors initially screened the published studies by their titles, and in a second step by the given abstract. Of these publications, all studies focusing on follow-up strategies after primary treatment of eSTS in adults were included. Publications with no mention of follow-up, those addressing pediatric STS, bone sarcoma, or STS at other locations than the limbs were excluded from the review. Studies comprising patients with eSTS, abdominal STS or gastrointestinal stromal tumors, leiomyosarcoma of the uterus or bone sarcoma were included when there was a clear distinction between eSTS and other STS or bone sarcoma. No publication was excluded on the basis of sample size or type of study because all of these were considered valuable for analysis. However, these factors were taken into account when interpreting the results.

Results

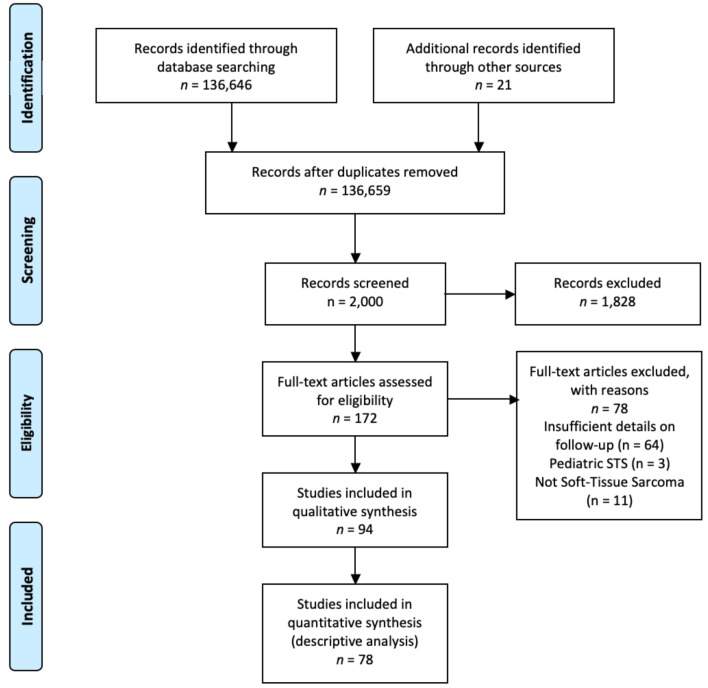

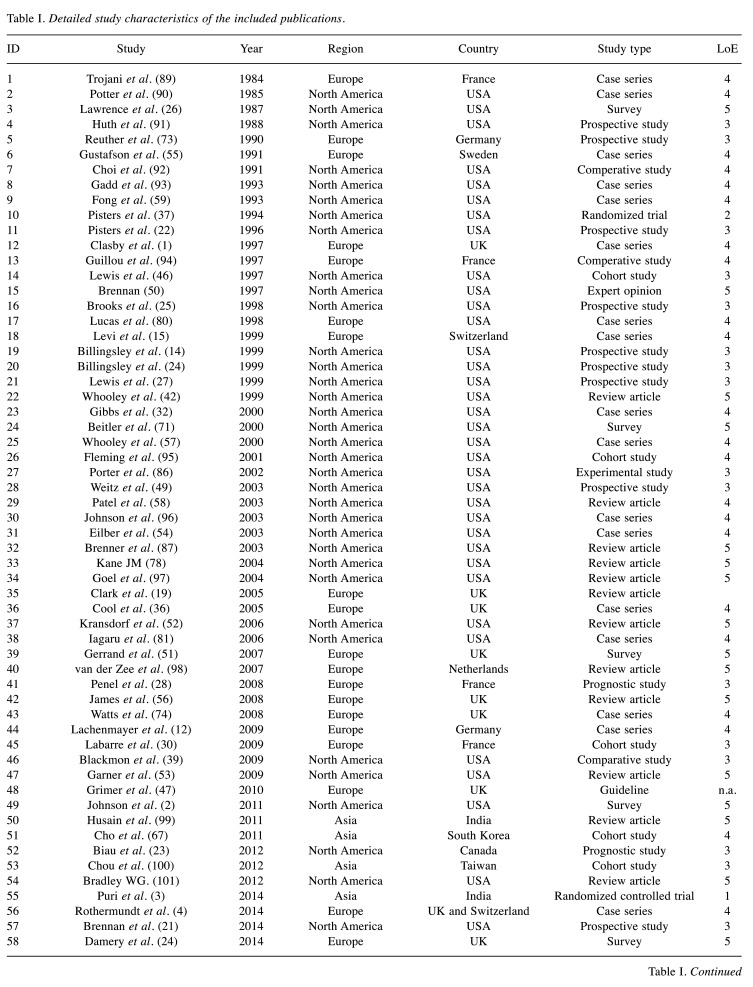

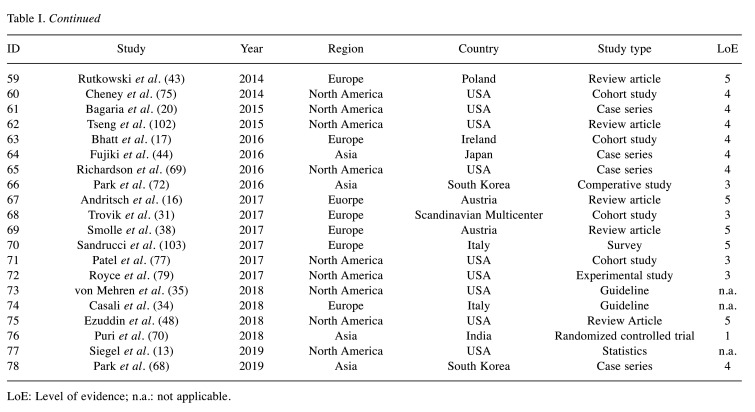

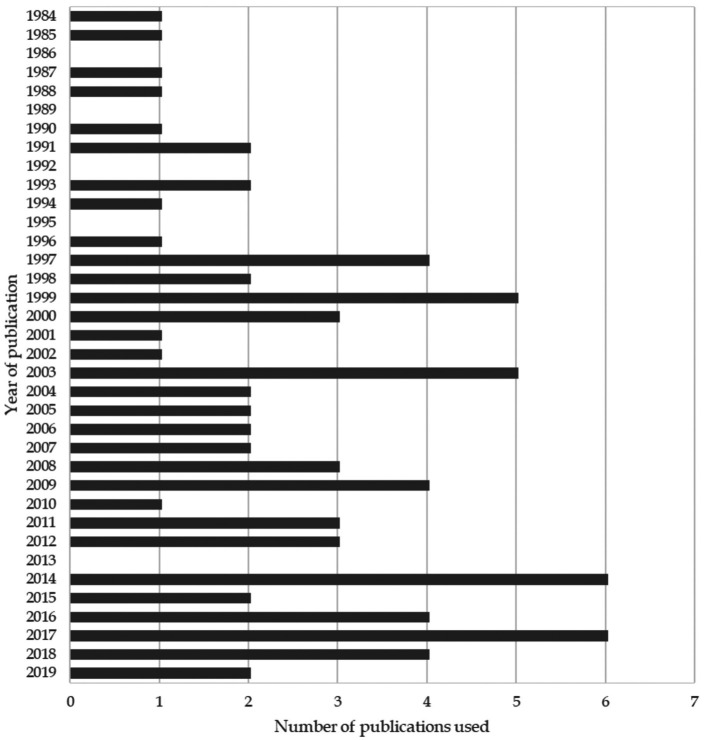

In all, 136,646 studies were identified. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 78 were deemed eligible for the analysis. Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of the study and the literature selection process according to the PRISMA checklist (41). Detailed study characteristics and the years of publication are presented in Table I and Figure 2.

Figure 1. Flow diagram according to PRISMA guidelines (41) showing study and literature selection process.

Table I. Detailed study characteristics of the included publications.

LoE: Level of evidence; n.a.: not applicable.

Figure 2. Distribution of year of publication of included studies.

The aim of follow-up after treatment for STS is early detection of LR and DM, because LR is observed in 40-60% of patients after therapy of eSTS (21,42). The majority of recurrences occurred in high-grade eSTS within the first 2 to 3 years of surveillance and were classified as early recurrence (1,32,43-46). Late recurrence may occur especially in low-grade eSTS but was found to be significantly less common than early recurrence (21,32,45,47). Since a recurrence may occur after 2 years (45) or more than 10 years of surveillance (21), the definition of a late recurrence is a crucial aspect. Risk factors influencing LR were found to be patient age (>50 years), deep location of the primary tumor (such as subfascial), primary tumor size (>5 cm), tumor grade (grade 2/3), and initial positive surgical margins (such as intralesional excision) (12,22,23,25,48-54).

The most common site (about 70%) of DM in eSTS was reported to be the lungs (14,24,42,43). Distant metastases in patients with eSTS are more frequently seen in large and deep high-grade STS (grade 2/3), independent of the histological subtype (24). Patients older than 50 years of age are at higher risk of developing DM (25,49). Moreover, the likelihood of DM is higher once the patient has developed LR, although no study has been able to prove a causal association between the two entities (22,36,46,49,50,55-57). According to some hypotheses, tumor persistence is a biological feature of sarcoma and occurs in conjunction with LR (46,55).

Although STS is known to spread by the hematological route,an embryonal variant of rhabdomyosarcoma in adults which spreads to the lymph nodes has been discovered (56,58,59). The most common histological subtypes that develop abdominal or retroperitoneal metastases are (myxoid) liposarcoma (60-62) and leiomyosarcomas (63-65). The published literature also mentions the occurrence of abdominal or retroperitoneal metastases in conjunction with rare histological subtypes such as epithelioid sarcoma (64), synovial sarcoma (64), malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (66) and myxofibrosarcoma (66).

Follow-up guidelines of Societies. A variety of follow-up schedules have been reported in the published literature. A fixed follow-up schedule for patients with eSTS permits timely detection of LR and metastatic disease (34,35). Two official guidelines have been approved by medical societies (34,35).

The guidelines issued by the ESMO make a distinction between low- and high-grade eSTS (34). For low-grade eSTS, the guidelines suggest radiological imaging and clinical investigation of the primary tumor site every 4 to 6 months for a period of 3 to 5 years, and annually thereafter (34). Chest imaging (X-ray or CT) may be performed less frequently but no precise recommendations are provided (34). For high-grade eSTS, the guidelines recommend follow-up intervals of 3 to 4 months for 2 to 3 years, and 6-month intervals until 5 years after treatment (34). Yearly investigations are advised after 5 years (34). The ESMO guidelines include clinical examination of the primary tumor site and chest imaging (not specified further) in any surveillance visit of patients with high-grade tumors (34). In general, the guidelines recommend an individual risk assessment in accordance with this directory (34).

The guidelines issued by the NCCN distinguish between follow-up strategies for American Joint Committee on Cancer stage IA/IB, stage II/III and stage IV lesions (35). For stage IA/IB, the guidelines recommend history-taking and physical examination every 3 to 6 months for a period of 2 to 3 years, and at yearly intervals thereafter (35). Distant (especially chest) and local imaging are advised with due consideration to the patient’s risks; an interval of 6 to 12 months is suggested (35). Stage II/III tumors should be monitored every 3 to 6 months for 2 to 3 years, every 6 months for another 2 years, and then annually; the follow-up investigation must include history-taking, physical examination, and chest imaging (35). Local imaging should be performed under consideration of the patient’s individual risk but is advised as a routine measure in those with unresectable disease (35). Follow-up investigations of high-stage eSTS should include history-taking, physical examination, chest imaging, and local imaging dependent on individual risk factors. These investigations should be conducted at 2- to 6-month intervals for 2 to 3 years, 6-month intervals for a further 2 years, and yearly intervals thereafter (35). However, neither the ESMO nor the NCCN guidelines mention a specific endpoint for follow-up (34,35).

Follow-up regimens in the published literature. Notwithstanding the diverse intervals for surveillance after the treatment of eSTS, the authors of published studies recommend increasingly frequent follow-up investigations (23,36,44,51,58,67-69). Follow-up investigations should be ideally performed at 3- to 4-month intervals for the first 2 years after surgery (23,36,44,51,58,67-69), and at 6-month intervals until the fifth year (1,23,36,44,51,58,67-69). This should be followed by yearly surveillance visits for a further 5 years, although a number of research groups did not specify an endpoint (23,36,44,58,67-69).

In a prospective study of eSTS follow-up, Puri et al. noted that less frequent follow-up does not result in higher recurrence rates (3,70). They suggest 6-month intervals for the first 5 years of surveillance, and yearly intervals for a further 5 years (3,70). However, more frequent visits might be indicated for certain high-grade eSTS. Therefore, the individual risk assessment remains important (70). Damery et al. examined patient preferences for follow-up and ascertained that an interval of 6 months over a total duration of 5 years is the most acceptable option for patients with sarcoma (29).

Imaging. In addition to the frequency of follow-up, the follow-up modality for local and metastatic disease is a debated issue. For local control, all reviewed studies agreed that history-taking and physical examination, or at least the latter, should be a part of every follow-up visit (14,29,31,36,44,47,51,52,57,58,67-69,71).

In addition to local physical examination, MRI scans should be considered especially for non-palpable eSTS (44,52,53,68,72-74). Suspicious palpable lesions must be investigated by MRI (47,75). With regard to distant metastasis, all authors suggest that some type of chest imaging must be conducted at every follow-up visit; the most accurate imaging modality is still a debated issue (3,24,36,44,51,57,67,69,71,76,77). While the large majority of authors believe that a chest X-ray is sufficient for routine surveillance, some regard a chest CT as the appropriate modality for the detection of lung metastases (3,24,31,36,44,51,57,67,69,71,77). Puri et al. found no evidence of potential superiority of chest CT over plain chest radiographs in the detection of lung metastases (3). Four other research groups concluded that chest X-ray suffices as a routine imaging modality; a chest CT scan should be obtained in the event of suspicious findings on the chest X-ray (14,36,44,57). After interviewing clinicians who treated patients with eSTS in the UK, Gerrand et al. concluded that a chest CT is rarely performed as a routine imaging modality for lung metastasis (51). Chest X-ray also appears to be given preference by patients, and is mentioned as the cost-effective option for primary eSTS and low-grade eSTS (29,57,58,78,79). According to the report published by Gerrand et al., it is current practice in the UK to perform routine imaging in high-risk patients (51).

Fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography (FDG-PET) has been discussed as an imaging modality for LR and metastatic spread to the lungs. However, it was proven inferior to MRI (for LR) and chest CT (for follow-up after resected eSTS). FDG-PET is not recommended as the first choice for the detection of LR and pulmonary metastases (80,81), but is a valuable tool for identifying extrapulmonary visceral spread (80).

Discussion

We analyzed original articles addressing follow-up strategies after the treatment of primary eSTS. The published literature revealed no clear consensus in regard to follow-up schedules. Although the diagnosis and treatment of these entities have improved markedly over the last few decades, the follow-up regimen has not changed over time (40). We aimed to summarize current approaches and provide an overview of existing follow-up regimens after primary treatment of eSTS. The strategies are analyzed in terms of the duration and frequency of follow-up as well as the most suitable imaging procedure.

Follow-up frequency. Postoperative follow-up after the treatment of primary eSTS, with or without curative intent, was shown to be important because it improves overall survival (71). A strict schedule contributes to early detection of LR and DM, and also helps to provide timely psychological support for the patient (19). However, the enforcement of strict follow-up regimens for all patients with eSTS has raised public, scientific, and economic concerns in recent years (5).

The risk of developing LR or DM is associated with numerous factors, such as histological STS subtype, tumor grade, tumor size, surgical margins, (neo-) adjuvant radiotherapy or chemotherapy, and patient-related factors (6-9,82-84). Our literature search revealed no clear consensus as to when and how often follow-up investigations should be performed for these patients (5,34,35). A heuristic approach is pursued at many centers: the guidelines mention 3 - to 4-month intervals during the first 3 years after surgery, every 6 months for the following 2 years, and at yearly intervals thereafter (5,34,35). Damery et al. examined patient preferences for follow-up and found that an interval of 6 months for a total duration of 5 years is most acceptable to patients with sarcoma (29). However, the current “one-follow-up-stategy-fits-all” approach may neglect the differing degrees of risk in the diverse eSTS population, and culminate in excessive surveillance for some patients. This might result in superfluous radiation exposure for patients and a significant workload for radiology departments (5,34,35).

By contrast, the absence of a regular follow-up strategy may result in a large number of patient visits to the Outpatient Department, significant costs of health care, and mental stress for the patient (5,85). Recently Smolle et al. published a model to predict the individual patient’s risk of LR and DM during follow-up; the authors used a flexible parametric approach of competing risk regression (5). These models were incorporated in the PERSARC app for individualized sarcoma care and monitoring (5,85). The limitations of the study performed by Smolle et al. include its retrospective nature, which may have resulted in a selection bias concerning diagnosis, treatment, and other aspects. However, it should be noted that their study was the first and the largest investigation of individualized follow-up strategies for high-grade eSTS with a flexible parametric model of competing risk regression (5). The study offers an evidence-based option of individual scheduling rather than adherence to calendar-based guidelines for follow-up investigations (5,34,35). The authors recommend much fewer radiological investigations for the assessment of disease status, especially after R0 resection, and take histological subtypes into account. Thus, the burden on the patient and the healthcare system is reduced (5). The use of flexible parametric models of competing risk regression to estimate the risk of LR and DM in eSTS patients is based on the fact that the risks do not increase or decrease consistently but vary markedly over time (5). However, a large-scale prospective investigation of eSTS is hindered by the rarity of this entity and the low percentage of resulting deaths (13). Furthermore, the issuance of guidelines is hindered by the diverse types of STS, and differences in their location, grade, size, and histology. Individualized follow-up might serve as a useful option for patients with eSTS.

Imaging. All of the reviewed studies agree that history-taking and physical examination, or at least the latter, should be a part of every follow-up visit (14,29,31,36,44,47,51,52,57,58,67-69,71). Tumor characteristics (location, size, grade, etc.) have a strong impact on the LR rate (23,36,44,51,58,67-69), and imply the need for follow-up imaging. In addition to the physical examination, MRI scans should be considered especially in cases of non-palpable eSTS (44,52,53,68,72-74). The published literature reveals that MRI is the best choice for local surveillance (44,52,53,68,72-74,77). Patient factors, such as a non-compatible pacemaker, claustrophobia, metal, or prostheses reduce the suitability of MRI. CT or PET-CT may be used in these instances but is less specific than MRI (72,73). Additionally, in a compliant patient with an eSTS in a superficial location, an assessment by the clinician or patient may reduce the need for local imaging because autodetection of LR has been reported in more than 50% of cases (3,4,43). Suspicious palpable lesions must be investigated further (47,75).

A comprehensive follow-up stategy should include local control as well as systemic surveillance (14,24,42,43). Concerning DM, all publications recommended chest imaging at every visit, although the authors were not unanimous about whether a chest X-ray (79,86) or a chest CT (3,24,31,36,44,51,57,67,69,71,77) is the most accurate modality. The latter modalities are the main tools of surveillance for potential metastases in the lung (79,86). Chest X-rays are considered equivalent to chest CT (3,70). Radiation exposure during a CT scan is 100-fold higher than the effective dose of an X-ray, thus raising the likelihood of carcinogenesis (87,88). CT scans or X-rays of the chest and MRI scans of the primary tumor site are well accepted. Ultrasound or CT scans of the abdomen are not obtained on a routine basis (34). eSTS is known to spread to any region of the body, including the abdomen, brain, bones and the retroperitoneum (40). However, these metastases are considered rare (40). Therefore, further diagnostic investigations such as an MRI of the brain or a CT scan of the abdomen are usually obtained when a patient has corresponding symptoms (40). Computed tomographic scans or ultrasonography of the abdomen, and even whole-body MRI should be used for early detection of metastases in the abdomen or the retroperitoneum, when the disease is still amenable to surgical resection (40). Additional FDG-PET is a valuable tool for the detection of extrapulmonary visceral metastatic spread (80).

We conclude that patients with eSTS must be followed-up at specialized sarcoma centers, although this may signify a challenge for the patient in terms of distance and accessibility.

The primary limitation of this systematic literature review is that the minimized exclusion criteria might have led to unjustified conclusions. However, we did take sample size and the hierarchy of evidence into account. The main strengths of the review are its novelty, broad basis, and the heterogeneity of the database.

Conclusion

Further research on follow-up strategies for eSTS is an urgent necessity. A small number of the numerous aspects of follow-up have been adequately researched and can be recommended without hesitation. These include the intervals of follow-up examinations. A 6-month interval between clinic visits appears to suffice, and was not inferior to shorter intervals. Furthermore, routine chest X-rays may be recommended for the detection of lung metastases. A CT of the chest should be considered as a secondary imaging modality when the chest X-ray reveals suspicious findings. An individualized follow-up strategy using a standardized flow chart for typical tumor or patient characteristics is currently being developed but calls for further improvement. The additional value of follow-up flow charts is yet to be proven. Further investigation and standardization are undoubtedly needed in this field.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contributions

D. Dammerer: Study protocol, study design, literature research, data analysis, editing and writing of the article. A. Van Beeck: Data analysis, co-editing, writing and proofreading of the article. V. Schneeweiß performed the literature research, data analysis and proofreading of the article. A. Schwabegger supervised the study results and proofread the article. All Authors made pertinent contributions to the article, and proofread and approved the final article before submission

References

- 1.Clasby R, Tilling K, Smith MA, Fletcher CD. Variable management of soft tissue sarcoma: Regional audit with implications for specialist care. Br J Surg. 1997;84(12):1692–1696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson FE, Sakata K, Sarkar S, Audisio RA, Kraybill WG, Gibbs JF, Beitler AL, Virgo KS. Patient surveillance after treatment for soft-tissue sarcoma. Int J Oncol. 2011;38(1):233–239. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puri A, Gulia A, Hawaldar R, Ranganathan P, Badwe RA. Does intensity of surveillance affect survival after surgery for sarcomas? Results of a randomized noninferiority trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(5):1568–1575. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3385-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rothermundt C, Whelan JS, Dileo P, Strauss SJ, Coleman J, Briggs TW, Haile SR, Seddon BM. What is the role of routine follow-up for localised limb soft tissue sarcomas? A retrospective analysis of 174 patients. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(10):2420–2426. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smolle MA, Sande MV, Callegaro D, Wunder J, Hayes A, Leitner L, Bergovec M, Tunn PU, van Praag V, Fiocco M, Panotopoulos J, Willegger M, Windhager R, Dijkstra SPD, van Houdt WJ, Riedl JM, Stotz M, Gerger A, Pichler M, Stöger H, Liegl-Atzwanger B, Smolle J, Andreou D, Leithner A, Gronchi A, Haas RL, Szkandera J. Individualizing follow-up strategies in high-grade soft-tissue sarcoma with flexible parametric competing risk regression models. Cancers (Basel) 2019;12(1) doi: 10.3390/cancers12010047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Italiano A, Le Cesne A, Mendiboure J, Blay JY, Piperno-Neumann S, Chevreau C, Delcambre C, Penel N, Terrier P, Ranchere-Vince D, Lae M, Le Guellec S, Michels JJ, Robin YM, Bellera C, Bonvalot S. Prognostic factors and impact of adjuvant treatments on local and metastatic relapse of soft-tissue sarcoma patients in the competing risks setting. Cancer. 2014;120(21):3361–3369. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maretty-Nielsen K, Aggerholm-Pedersen N, Safwat A, Jørgensen PH, Hansen BH, Baerentzen S, Pedersen AB, Keller J. Prognostic factors for local recurrence and mortality in adult soft tissue sarcoma of the extremities and trunk wall: A cohort study of 922 consecutive patients. Acta Orthop. 2014;85(3):323–332. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2014.90834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Novais EN, Demiralp B, Alderete J, Larson MC, Rose PS, Sim FH. Do surgical margin and local recurrence influence survival in soft tissue sarcomas. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(11):3003–3011. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1471-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willeumier J, Fiocco M, Nout R, Dijkstra S, Aston W, Pollock R, Hartgrink H, Bovée J, van de Sande M. High-grade soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities: Surgical margins influence only local recurrence not overall survival. Int Orthop. 2015;39(5):935–941. doi: 10.1007/s00264-015-2694-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singer S, Demetri GD, Baldini EH, Fletcher CD. Management of soft-tissue sarcomas: An overview and update. Lancet Oncol. 2000;1:75–85. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(00)00016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hogendoorn PCW, Mertens F, editors. Geneva: IARC Press. 2013. Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. Fourth Edition; pp. 83–84. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lachenmayer A, Yang Q, Eisenberger CF, Boelke E, Poremba C, Heinecke A, Ohmann C, Knoefel WT, Peiper M. Superficial soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities and trunk. World J Surg. 2009;33(8):1641–1649. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Billingsley KG, Lewis JJ, Leung DH, Casper ES, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Multifactorial analysis of the survival of patients with distant metastasis arising from primary extremity sarcoma. Cancer. 1999;85(2):389–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levi F, La Vecchia C, Randimbison L, Te VC. Descriptive epidemiology of soft tissue sarcomas in vaud, switzerland. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35(12):1711–1716. doi: 10.1159/000110763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andritsch E, Beishon M, Bielack S, Bonvalot S, Casali P, Crul M, Delgado Bolton R, Donati DM, Douis H, Haas R, Hogendoorn P, Kozhaeva O, Lavender V, Lovey J, Negrouk A, Pereira P, Roca P, de Lempdes GR, Saarto T, van Berck B, Vassal G, Wartenberg M, Yared W, Costa A, Naredi P. Ecco essential requirements for quality cancer care: Soft tissue sarcoma in adults and bone sarcoma. A critical review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;110:94–105. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhatt N, Deady S, Gillis A, Bertuzzi A, Fabre A, Heffernan E, Gillham C, O’Toole G, Ridgway PF. Epidemiological study of soft-tissue sarcomas in ireland. Cancer Med. 2016;5(1):129–135. doi: 10.1002/cam4.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Posch F, Leitner L, Bergovec M, Bezan A, Stotz M, Gerger A, Pichler M, Stöger H, Liegl-Atzwanger B, Leithner A, Szkandera J. Can multistate modeling of local recurrence, distant metastasis, and death improve the prediction of outcome in patients with soft tissue sarcomas. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475(5):1427–1435. doi: 10.1007/s11999-017-5232-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark MA, Fisher C, Judson I, Thomas JM. Soft-tissue sarcomas in adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(7):701–711. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bagaria SP, Wagie AE, Gray RJ, Pockaj BA, Attia S, Habermann EB, Wasif N. Validation of a soft tissue sarcoma nomogram using a national cancer registry. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22 Suppl 3:S398–403. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4849-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brennan MF, Antonescu CR, Moraco N, Singer S. Lessons learned from the study of 10,000 patients with soft tissue sarcoma. Ann Surg. 2014;260(3):416–421. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000869. discussion 421-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pisters PW, Leung DH, Woodruff J, Shi W, Brennan MF. Analysis of prognostic factors in 1,041 patients with localized soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(5):1679–1689. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.5.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biau DJ, Ferguson PC, Chung P, Griffin AM, Catton CN, O’Sullivan B, Wunder JS. Local recurrence of localized soft tissue sarcoma: A new look at old predictors. Cancer. 2012;118(23):5867–5877. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Billingsley KG, Burt ME, Jara E, Ginsberg RJ, Woodruff JM, Leung DH, Brennan MF. Pulmonary metastases from soft tissue sarcoma: Analysis of patterns of diseases and postmetastasis survival. Ann Surg. 1999;229(5):602–610. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199905000-00002. discussion 610-602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brooks AD, Heslin MJ, Leung DH, Lewis JJ, Brennan MF. Superficial extremity soft tissue sarcoma: An analysis of prognostic factors. Ann Surg Oncol. 1998;5(1):41–47. doi: 10.1007/BF02303763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawrence W, Donegan WL, Natarajan N, Mettlin C, Beart R, Winchester D. Adult soft tissue sarcomas. A pattern of care survey of the american college of surgeons. Ann Surg. 1987;205(4):349–359. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198704000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis JJ, Leung D, Casper ES, Woodruff J, Hajdu SI, Brennan MF. Multifactorial analysis of long-term follow-up (more than 5 years) of primary extremity sarcoma. Arch Surg. 1999;134(2):190–194. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Penel N, Grosjean J, Robin YM, Vanseymortier L, Clisant S, Adenis A. Frequency of certain established risk factors in soft tissue sarcomas in adults: A prospective descriptive study of 658 cases. Sarcoma. 2008;2008:459386. doi: 10.1155/2008/459386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Damery S, Biswas M, Billingham L, Barton P, Al-Janabi H, Grimer R. Patient preferences for clinical follow-up after primary treatment for soft tissue sarcoma: A cross-sectional survey and discrete choice experiment. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40(12):1655–1661. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Labarre D, Aziza R, Filleron T, Delannes M, Delaunay F, Marques B, Ferron G, Chevreau C. Detection of local recurrences of limb soft tissue sarcomas: Is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) relevant. Eur J Radiol. 2009;72(1):50–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trovik C, Bauer HCF, Styring E, Sundby Hall K, Vult Von Steyern F, Eriksson S, Johansson I, Sampo M, Laitinen M, Kalén A, Jónsson H, Jebsen N, Eriksson M, Tukiainen E, Wall N, Zaikova O, Sigurðsson H, Lehtinen T, Bjerkehagen B, Skorpil M, Egil Eide G, Johansson E, Alvegard TA. The Scandinavian Sarcoma Group central register: 6,000 patients after 25 years of monitoring of referral and treatment of extremity and trunk wall soft-tissue sarcoma. Acta Orthop. 2017;88(3):341–347. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2017.1293441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gibbs JF, Lee RJ, Driscoll DL, McGrath BE, Mindell ER, Kraybill WG. Clinical importance of late recurrence in soft-tissue sarcomas. J Surg Oncol. 2000;73(2):81–86. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(200002)73:2<81::aid-jso5>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schlag PM, Hartmann JT, Budach V. Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg. 2011. Weichgewebetumoren: Interdisziplinäres management. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Casali PG, Abecassis N, Aro HT, Bauer S, Biagini R, Bielack S, Bonvalot S, Boukovinas I, Bovee JVMG, Brodowicz T, Broto JM, Buonadonna A, De Álava E, Dei Tos AP, Del Muro XG, Dileo P, Eriksson M, Fedenko A, Ferraresi V, Ferrari A, Ferrari S, Frezza AM, Gasperoni S, Gelderblom H, Gil T, Grignani G, Gronchi A, Haas RL, Hassan B, Hohenberger P, Issels R, Joensuu H, Jones RL, Judson I, Jutte P, Kaal S, Kasper B, Kopeckova K, Krákorová DA, Le Cesne A, Lugowska I, Merimsky O, Montemurro M, Pantaleo MA, Piana R, Picci P, Piperno-Neumann S, Pousa AL, Reichardt P, Robinson MH, Rutkowski P, Safwat AA, Schöffski P, Sleijfer S, Stacchiotti S, Sundby Hall K, Unk M, Van Coevorden F, van der Graaf WTA, Whelan J, Wardelmann E, Zaikova O, Blay JY, EURACAN EGCa Soft tissue and visceral sarcomas: Esmo-euracan clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(Suppl 4):iv51–iv67. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.von Mehren M, Randall RL, Benjamin RS, Boles S, Bui MM, Ganjoo KN, George S, Gonzalez RJ, Heslin MJ, Kane JM, Keedy V, Kim E, Koon H, Mayerson J, McCarter M, McGarry SV, Meyer C, Morris ZS, O’Donnell RJ, Pappo AS, Paz IB, Petersen IA, Pfeifer JD, Riedel RF, Ruo B, Schuetze S, Tap WD, Wayne JD, Bergman MA, Scavone JL. Soft tissue sarcoma, version 2.2018, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16(5):536–563. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cool P, Grimer R, Rees R. Surveillance in patients with sarcoma of the extremities. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31(9):1020–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pisters PW, Harrison LB, Woodruff JM, Gaynor JJ, Brennan MF. A prospective randomized trial of adjuvant brachytherapy in the management of low-grade soft tissue sarcomas of the extremity and superficial trunk. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12(6):1150–1155. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.6.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smolle MA, Andreou D, Tunn PU, Szkandera J, Liegl-Atzwanger B, Leithner A. Diagnosis and treatment of soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities and trunk. EFORT Open Rev. 2017;2(10):421–431. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.2.170005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blackmon SH, Shah N, Roth JA, Correa AM, Vaporciyan AA, Rice DC, Hofstetter W, Walsh GL, Benjamin R, Pollock R, Swisher SG, Mehran R. Resection of pulmonary and extrapulmonary sarcomatous metastases is associated with long-term survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88(3):877–884. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.04.144. discussion 884-875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smolle MA, Leithner A, Bernhardt GA. Abdominal metastases of primary extremity soft tissue sarcoma: A systematic review. World J Clin Oncol. 2020;11(2):74–82. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v11.i2.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The prisma statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whooley BP, Mooney MM, Gibbs JF, Kraybill WG. Effective follow-up strategies in soft tissue sarcoma. Semin Surg Oncol. 1999;17(1):83–87. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2388(199907/08)17:1<83::aid-ssu11>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rutkowski P, Lugowska I. Follow-up in soft tissue sarcomas. Memo. 2014;7(2):92–96. doi: 10.1007/s12254-014-0146-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fujiki M, Miyamoto S, Kobayashi E, Sakuraba M, Chuman H. Early detection of local recurrence after soft tissue sarcoma resection and flap reconstruction. Int Orthop. 2016;40(9):1975–1980. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3219-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Potter DA, Glenn J, Kinsella T, Glatstein E, Lack EE, Restrepo C, White DE, Seipp CA, Wesley R, Rosenberg SA. Patterns of recurrence in patients with high-grade soft-tissue sarcomas. J Clin Oncol. 1985;3(3):353–366. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1985.3.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lewis JJ, Leung D, Heslin M, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Association of local recurrence with subsequent survival in extremity soft tissue sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(2):646–652. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.2.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grimer R, Judson I, Peake D, Seddon B. Guidelines for the management of soft tissue sarcomas. Sarcoma. 2010;2010:506182. doi: 10.1155/2010/506182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ezuddin NS, Pretell-Mazzini J, Yechieli RL, Kerr DA, Wilky BA, Subhawong TK. Local recurrence of soft-tissue sarcoma: Issues in imaging surveillance strategy. Skeletal Radiol. 2018;47(12):1595–1606. doi: 10.1007/s00256-018-2965-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weitz J, Antonescu CR, Brennan MF. Localized extremity soft tissue sarcoma: Improved knowledge with unchanged survival over time. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(14):2719–2725. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brennan MF. The enigma of local recurrence. The Society of Surgical Oncology. Ann Surg Oncol. 1997;4(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/BF02316804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gerrand CH, Billingham LJ, Woll PJ, Grimer RJ. Follow up after primary treatment of soft tissue sarcoma: A survey of current practice in the United Kingdom. Sarcoma. 2007;2007:4128. doi: 10.1155/2007/34128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kransdorf MJ, Murphey MD. Soft tissue tumors: Post-treatment imaging. Radiol Clin North Am. 2006;44(3):463–472. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garner HW, Kransdorf MJ, Bancroft LW, Peterson JJ, Berquist TH, Murphey MD. Benign and malignant soft-tissue tumors: Posttreatment MR imaging. Radiographics. 2009;29(1):119–134. doi: 10.1148/rg.291085131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eilber FC, Rosen G, Nelson SD, Selch M, Dorey F, Eckardt J, Eilber FR. High-grade extremity soft tissue sarcomas: Factors predictive of local recurrence and its effect on morbidity and mortality. Ann Surg. 2003;237(2):218–226. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000048448.56448.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gustafson P, Rööser B, Rydholm A. Is local recurrence of minor importance for metastases in soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer. 1991;67(8):2083–2086. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910415)67:8<2083::aid-cncr2820670813>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.James SL, Davies AM. Post-operative imaging of soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer Imaging. 2008;8:8–18. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2008.0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Whooley BP, Gibbs JF, Mooney MM, McGrath BE, Kraybill WG. Primary extremity sarcoma: What is the appropriate follow-up. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7(1):9–14. doi: 10.1007/s10434-000-0009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Patel SR, Zagars GK, Pisters PW. The follow-up of adult soft-tissue sarcomas. Semin Oncol. 2003;30(3):413–416. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(03)00101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fong Y, Coit DG, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Lymph node metastasis from soft tissue sarcoma in adults. Analysis of data from a prospective database of 1772 sarcoma patients. Ann Surg. 1993;217(1):72–77. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199301000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gorelik N, Reddy SMV, Turcotte RE, Goulding K, Jung S, Alcindor T, Powell TI. Early detection of metastases using whole-body MRI for initial staging and routine follow-up of myxoid liposarcoma. Skeletal Radiol. 2018;47(3):369–379. doi: 10.1007/s00256-017-2845-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sheah K, Ouellette HA, Torriani M, Nielsen GP, Kattapuram S, Bredella MA. Metastatic myxoid liposarcomas: Imaging and histopathologic findings. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37(3):251–258. doi: 10.1007/s00256-007-0424-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Behranwala KA, Roy P, Giblin V, A’hern R, Fisher C, Thomas JM. Intra-abdominal metastases from soft tissue sarcoma. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87(3):116–120. doi: 10.1002/jso.20105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grimme FAB, Seesing MFJ, van Hillegersberg R, van Coevorden F, de Jong KP, Nagtegaal ID, Verhoef C, de Wilt JHW, On behalf of the Dutch Liver Surgery Working Group Liver resection for hepatic metastases from soft tissue sarcoma: A nationwide study. Dig Surg. 2019;36(6):479–486. doi: 10.1159/000493389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thompson MJ, Ross J, Domson G, Foster W. Screening and surveillance ct abdomen/pelvis for metastases in patients with soft-tissue sarcoma of the extremity. Bone Joint Res. 2015;4(3):45–49. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.43.2000337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mizoshiri N, Shirai T, Terauchi R, Tsuchida S, Mori Y, Katsuyama Y, Hayashi D, Konishi E, Kubo T. Hepatic metastases from primary extremity leiomyosarcomas: Two case reports. Medicine. 2018;97(18):e0598. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.King DM, Hackbarth DA, Kilian CM, Carrera GF. Soft-tissue sarcoma metastases identified on abdomen and pelvis ct imaging. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(11):2838–2844. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0989-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cho HS, Park IH, Jeong WJ, Han I, Kim HS. Prognostic value of computed tomography for monitoring pulmonary metastases in soft tissue sarcoma patients after surgical management: A retrospective cohort study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(12):3392–3398. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1705-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Park JW, Yoo HJ, Kim HS, Choi JY, Cho HS, Hong SH, Han I. MRI surveillance for local recurrence in extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2019;45(2):268–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Richardson K, Potter M, Damron TA. Image intensive soft tissue sarcoma surveillance uncovers pathology earlier than patient complaints but with frequent initially indeterminate lesions. J Surg Oncol. 2016;113(7):818–822. doi: 10.1002/jso.24230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Puri A, Ranganathan P, Gulia A, Crasto S, Hawaldar R, Badwe RA. Does a less intensive surveillance protocol affect the survival of patients after treatment of a sarcoma of the limb? Updated results of the randomized toss study. Bone Joint J. 2018;100-B(2):262–268. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.100B2.BJJ-2017-0789.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Beitler AL, Virgo KS, Johnson FE, Gibbs JF, Kraybill WG. Current follow-up strategies after potentially curative resection of extremity sarcomas: Results of a survey of the members of the Society of Surgical Oncology. Cancer. 2000;88(4):777–785. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000215)88:4<777::AID-CNCR7>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Park SY, Chung HW, Chae SY, Lee JS. Comparison of mri and pet-ct in detecting the loco-regional recurrence of soft tissue sarcomas during surveillance. Skeletal Radiol. 2016;45(10):1375–1384. doi: 10.1007/s00256-016-2440-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Reuther G, Mutschler W. Detection of local recurrent disease in musculoskeletal tumors: Magnetic resonance imaging versus computed tomography. Skeletal Radiol. 1990;19(2):85–90. doi: 10.1007/BF00197611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Watts AC, Teoh K, Evans T, Beggs I, Robb J, Porter D. MRI surveillance after resection for primary musculoskeletal sarcoma. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(4):484–487. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B4.20089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cheney MD, Giraud C, Goldberg SI, Rosenthal DI, Hornicek FJ, Choy E, Mullen JT, Chen YL, Delaney TF. MRI surveillance following treatment of extremity soft tissue sarcoma. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109(6):593–596. doi: 10.1002/jso.23541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tsagozis P, Bauer HC, Styring E, Trovik CS, Zaikova O, Brosjö O. Prognostic factors and follow-up strategy for superficial soft-tissue sarcomas: Analysis of 622 surgically treated patients from the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group register. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111(8):951–956. doi: 10.1002/jso.23927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Patel SA, Royce TJ, Barysauskas CM, Thornton KA, Raut CP, Baldini EH. Surveillance imaging patterns and outcomes following radiation therapy and radical resection for localized extremity and trunk soft tissue sarcoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(6):1588–1595. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5755-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kane JM. Surveillance strategies for patients following surgical resection of soft tissue sarcomas. Curr Opin Oncol. 2004;16(4):328–332. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000127879.62254.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Royce TJ, Punglia RS, Chen AB, Patel SA, Thornton KA, Raut CP, Baldini EH. Cost-effectiveness of surveillance for distant recurrence in extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(11):3264–3270. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5996-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lucas JD, O’Doherty MJ, Wong JC, Bingham JB, McKee PH, Fletcher CD, Smith MA. Evaluation of fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in the management of soft-tissue sarcomas. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80(3):441–447. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.80b3.8232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Iagaru A, Chawla S, Menendez L, Conti PS. 18f-fdg pet and pet/ct for detection of pulmonary metastases from musculoskeletal sarcomas. Nucl Med Commun. 2006;27(10):795–802. doi: 10.1097/01.mnm.0000237986.31597.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gingrich AA, Bateni SB, Monjazeb AM, Darrow MA, Thorpe SW, Kirane AR, Bold RJ, Canter RJ. Neoadjuvant radiotherapy is associated with r0 resection and improved survival for patients with extremity soft tissue sarcoma undergoing surgery: A national cancer database analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(11):3252–3263. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-6019-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gronchi A, Ferrari S, Quagliuolo V, Broto JM, Pousa AL, Grignani G, Basso U, Blay JY, Tendero O, Beveridge RD, Ferraresi V, Lugowska I, Merlo DF, Fontana V, Marchesi E, Donati DM, Palassini E, Palmerini E, De Sanctis R, Morosi C, Stacchiotti S, Bagué S, Coindre JM, Dei Tos AP, Picci P, Bruzzi P, Casali PG. Histotype-tailored neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus standard chemotherapy in patients with high-risk soft-tissue sarcomas (ISG-STS 1001): An international, open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 3, multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(6):812–822. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30334-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Posch F, Partl R, Döller C, Riedl JM, Smolle M, Leitner L, Bergovec M, Liegl-Atzwanger B, Stotz M, Bezan A, Gerger A, Pichler M, Kapp KS, Stöger H, Leithner A, Szkandera J. Benefit of adjuvant radiotherapy for local control, distant metastasis, and survival outcomes in patients with localized soft tissue sarcoma: Comparative effectiveness analysis of an observational cohort study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(3):776–783. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-6080-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.van Praag VM, Rueten-Budde AJ, Jeys LM, Laitinen MK, Pollock R, Aston W, van der Hage JA, Dijkstra PDS, Ferguson PC, Griffin AM, Willeumier JJ, Wunder JS, van de Sande MAJ, Fiocco M. A prediction model for treatment decisions in high-grade extremity soft-tissue sarcomas: Personalised sarcoma care (PERSARC) Eur J Cancer. 2017;83:313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Porter GA, Cantor SB, Ahmad SA, Lenert JT, Ballo MT, Hunt KK, Feig BW, Patel SR, Benjamin RS, Pollock RE, Pisters PW. Cost-effectiveness of staging computed tomography of the chest in patients with T2 soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer. 2002;94(1):197–204. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Brenner DJ, Doll R, Goodhead DT, Hall EJ, Land CE, Little JB, Lubin JH, Preston DL, Preston RJ, Puskin JS, Ron E, Sachs RK, Samet JM, Setlow RB, Zaider M. Cancer risks attributable to low doses of ionizing radiation: Assessing what we really know. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(24):13761–13766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235592100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Reiser M, Kuhn F-P, Debus J. Georg Thieme Verlag KG. 2011. Radiologie. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Trojani M, Contesso G, Coindre JM, Rouesse J, Bui NB, de Mascarel A, Goussot JF, David M, Bonichon F, Lagarde C. Soft-tissue sarcomas of adults; study of pathological prognostic variables and definition of a histopathological grading system. Int J Cancer. 1984;33(1):37–42. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910330108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Potter DA, Glenn J, Kinsella T, Glatstein E, Lack EE, Restrepo C, White DE, Seipp CA, Wesley R, Rosenberg SA. Patterns of recurrence in patients with high-grade soft-tissue sarcomas. J Clin Oncol. 1985;3(3):353–366. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1985.3.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Huth JF, Eilber FR. Patterns of metastatic spread following resection of extremity soft-tissue sarcomas and strategies for treatment. Semin Surg Oncol. 1988;4(1):20–26. doi: 10.1002/ssu.2980040106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Choi H, Varma DG, Fornage BD, Kim EE, Johnston DA. Soft-tissue sarcoma: MR imaging vs. sonography for detection of local recurrence after surgery. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157(2):353–358. doi: 10.2214/ajr.157.2.1853821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gadd MA, Casper ES, Woodruff JM, McCormack PM, Brennan MF. Development and treatment of pulmonary metastases in adult patients with extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Ann Surg. 1993;218(6):705–712. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199312000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Guillou L, Coindre JM, Bonichon F, Nguyen BB, Terrier P, Collin F, Vilain MO, Mandard AM, Le Doussal V, Leroux A, Jacquemier J, Duplay H, Sastre-Garau X, Costa J. Comparative study of the National Cancer Institute and French Federation of Cancer Centers Sarcoma Group grading systems in a population of 410 adult patients with soft tissue sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(1):350–362. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.1.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fleming JB, Cantor SB, Varma DG, Holst D, Feig BW, Hunt KK, Patel SR, Benjamin RS, Pollock RE, Pisters PW. Utility of chest computed tomography for staging in patients with T1 extremity soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer. 2001;92(4):863–868. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010815)92:4<863::aid-cncr1394>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Johnson GR, Zhuang H, Khan J, Chiang SB, Alavi A. Roles of positron emission tomography with fluorine-18-deoxyglucose in the detection of local recurrent and distant metastatic sarcoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2003;28(10):815–820. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000089523.00672.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Goel A, Christy MEL, Virgo KS, Kraybill WG, Johnson FE. Costs of follow-up after potentially curative treatment for extremity soft-tissue sarcoma. Int J Oncol. 2004;25(2):429–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.van der Zee J, Kroneman MW. Bismarck or Beveridge: a beauty contest between dinosaurs. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:94. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Husain N, Verma N. Curent concepts in pathology of soft tissue sarcoma. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2011;2(4):302–308. doi: 10.1007/s13193-012-0134-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chou Y-S, Liu C-Y, Chen W-M, Chen T-H, Chen PC-H, Wu H-TH, Chiou H-J, Shiau C-Y, Wu Y-C, Liu C-L, Chao T-C, Tzeng C-H, Yen C-C. Follow-up after primary treatment of soft tissue sarcoma of extremities: impact of frequency of follow-up imaging on disease-specific survival. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106(2):155–161. doi: 10.1002/jso.23060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bradley Jr WG. Teleradiology. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2012;22(3):511–517. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rutkowski P, Ługowska I. Follow-up in soft tissue sarcomas. Memo. 2014;7(2):92–96. doi: 10.1007/s12254-014-0146-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bleloch JS, Ballim RD, Kimani S, Parkes J, Panieri E, Willmer T, Prince S. Managing sarcoma: where have we come from and where are we going. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2017;9(10):637–659. doi: 10.1177/1758834017728927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]