Abstract

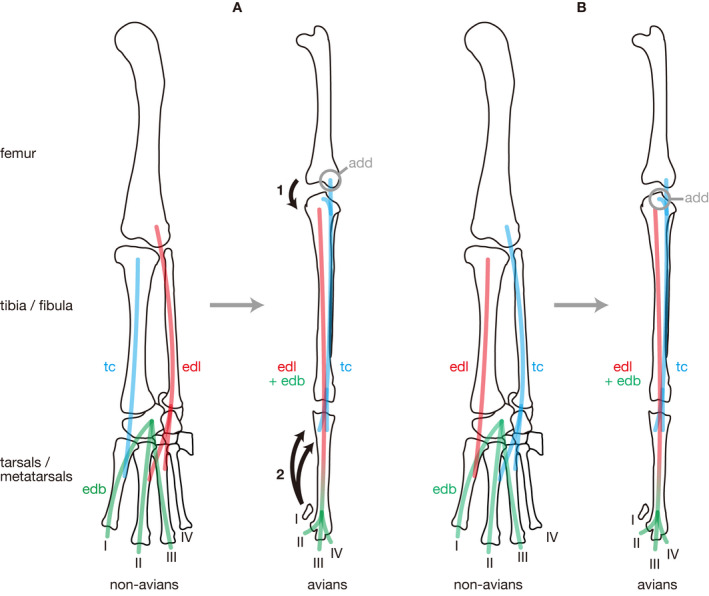

Archosaurs displayed an evolutionary trend toward increasing bipedalism in their evolutionary history, that is, forelimbs tend to be reduced in contrast to the development of hindlimbs becoming major weight‐bearing and locomotor appendages. The archosaurian locomotion has been extensively discussed based on their limb morphology because the latter reflects their locomotor modes very well. However, despite some attempts of reconstructing the hindlimb musculature in Archosauria, that of the most distal portion, the pes, has often been neglected. In order to rectify this trend, detailed homologies of pedal muscles among sauropsids were established based on dissections and literature reviews of adult conditions. As a result, homologies of some pedal muscles between non‐avian sauropsids and avians were revised, challenging classical hypotheses. The present new hypothesis postulates that the avian m. tibialis cranialis and non‐avian m. extensor digitorum longus, as well as the avian m. extensor digitorum longus and non‐avian m. tibialis anterior, are homologous with each other, respectively. This is more plausible because it requires no drastical change in the attachment sites between the avian and non‐avian homologues unlike the classical hypothesis. Many interosseous muscles in non‐archosaurian sauropsids that have long been regarded as a part of short digital extensors or flexors are also divided into multiple distinct muscles so that they can be homologized with short pedal muscles among all sauropsids. In addition, osteological correlates of attachments are identified for most of the pedal muscles, contributing to future attempts of reconstruction of this muscle system in fossil archosaurs.

Keywords: Archosauria, Aves, Crocodilia, homology, Lepidosauria, muscle, osteological correlates, pes, Sauropsida, Testudines

Despite some attempts of reconstructing the hindlimb musculature in Archosauria, that of the most distal portion, the pes, has often been neglected. In order to rectify this trend, detailed homologies of pedal muscles among sauropsids were established based on dissections and literature reviews of adult conditions. As a result, homologies of some pedal muscles between non‐avian sauropsids and avians were revised, challenging classical hypotheses. In addition, osteological correlates of attachments are identified for most of the pedal muscles, contributing to future attempts of reconstruction of this muscle system in fossil archosaurs.

1. INTRODUCTION

Since Romer’s (1923a, 1923b, 1927) pioneering work on the archosaurian limb myology based on comprehensive examinations on the relationship between osteological features and limb postures in lepidosaurs, crocodilians, and dinosaurs, locomotion in Archosauria has been extensively discussed in paleontology. Moreover, the recognition of avians (birds) as the descendants of Mesozoic theropod dinosaurs has led us to further understanding of major evolutionary changes in the limb morphology and function during the entire evolutionary history of Archosauria (Gatesy and Dial, 1996; Farlow et al., 2000; Hutchinson, 2009; Gauthier et al., 2011). Among archosaurs, the hindlimb of theropod dinosaurs is specialized for bipedal locomotion, which is inherited by extant avians. Although the main role of the hindlimb has not been altered from terrestrial locomotion within Theropoda, detailed morphology of this body part has been extensively modified on the line to Aves (Gatesy, 2002).

The musculature is fundamental for understanding locomotor functions and, thus, is the most often reconstructed aspect of the soft tissue anatomy in fossil vertebrates (e.g. Romer, 1927; Carrano and Hutchinson, 2002; Persons and Currie, 2011). Some muscle attachments leave distinct morphological signatures on bone surfaces, namely, osteological correlates, that are often preserved on fossils, such as muscle scars, crests, tubercles, trochanters, and smooth surfaces representing attachments or courses of muscles and/or tendons (Hutchinson, 2002; Burch, 2014).

Mostly based on the osteological correlates described above, reconstructions of the musculature in extinct vertebrates have been attempted for over 130 years. Relatively recently, a phylogenetically rigorous methodology for reconstructing soft anatomy in fossils was proposed (Bryant and Russell, 1993; Witmer, 1995). The methodology, widely known as the extant phylogenetic bracketing approach, is firmly based on homologous structures between at least two extant outgroups of the fossil taxon of interest and provides a criterion for rigorously establishing the limits of inferences (Witmer, 1995).

Despite some previous attempts of reconstructing the hindlimb musculature in archosaurs, the most distal portion of this body part, the pes, has often been neglected. Among many muscles associated with the pes, only those arising from more proximal portion of the hindlimb, i.e., thigh and crus, have been reconstructed, with intrinsic pedal muscles arising from and inserting on the pedal bones only briefly mentioned in past studies (Dilkes, 2000; Carrano and Hutchinson, 2002; Hutchinson, 2002). This trend is mainly because of the greater complexity of the skeleton and musculature in the pes compared to the more proximal portion, in which both bones and muscles are large and can be dissected more easily. In addition, Romer’s (1923a, 1923b) homology hypotheses of hindlimb muscles, which have been the basis for muscle reconstructions in fossil archosaurs even in recent years, did not deal with the distal segment of the hindlimb.

In order to infer evolutionary changes in the pedal muscles in Archosauria, their detailed homologies among sauropsid taxa need to be established. The first comprehensive review of the pedal musculature among extant non‐avian sauropsids (or commonly called ‘reptiles’) was the monograph of Gadow (1882). He established major divisions of pedal muscles, naming them with Roman numerals with further subdivisions indicated with Greek letters. In Gadow (1882), attachment areas of these muscles on bones were briefly described but were not figured, whereas the details of the innervation pattern of the pedal muscles were figured for Alligator mississippiensis only. More comprehensive descriptions of the innervation pattern of the pedal musculature were provided in the monographs by Ribbing (1909, 1938). However, he recognized only major divisions of muscles unlike Gadow (1882), focusing on homologies of such divisions among sauropsids and amphibians. Later, more detailed myological descriptions of the pes were undertaken for lepidosaurs (Russell and Bauer, 2008), testudines (Walker, 1973), crocodilians (Cong et al., 1998; Suzuki et al., 2011), and avians (Fujioka, 1962; Vanden Berge, 1975). Although these more recent descriptions provide detailed information on the hindlimb musculature including the pedal region, each study was focused on a narrow taxonomic range, with little consideration for homologies of muscles among taxa, especially between non‐avians and avians.

In addition, osteological correlates of muscle attachments have not been described in most anatomical studies. In the past, osteological correlates were examined in detail in studies specifically intended for paleontological applications (e.g. Hutchinson, 2001a, 2001b). However, as mentioned above, such a study is still lacking on the pedal region. For these reasons, the aim of the present study is to describe muscles associated with pedes in detail, compare their morphology, establish their homologies among extant sauropsids, and describe their osteological correlates for future paleontological applications.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

To observe the morphology of the pedal muscles in detail, the following specimens were dissected (the number in each bracket indicates the number of dissected specimens for each species): squamates Iguana iguana [2] and Varanus indicus [1], turtle Chelydra serpentina [1], crocodilians Paleosuchus palpebrosus [1] and Crocodylus porosus [2], and avians Gallus gallus [1] and Grus japonensis [1]. These specimens were fixed and preserved in aqueous solution of 70% ethanol except for Paleosuchus and one of Crocodylus, which were dissected without fixation. Positions and morphology of osteological correlates for muscle attachments were also directly observed in each dissected specimen (Figure 1).

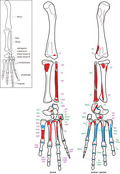

Figure 1.

Osteological correlates on the tarsometatarsus of Gallus gallus. (A) Left tarsometatarsus in dorsal view. (B) Drawing of muscle attachment sites (red) and their osteological correlates (black)

The nomenclature of the muscles follows Russell and Bauer (2008) for lepidosaurs, Walker (1973) for testudines, Suzuki et al. (2011) for crocodilians, and Vanden Berge and Zweers (1993) for avians. Putatively homologous muscles are described under each standardized name, which mostly follows nomenclature used in Suzuki et al. (2011). Although Suzuki et al. (2011) is the most detailed description of the crocodilian hindlimb muscles at this time, it is written in Japanese and thus difficult to understand for non‐Japanese researchers. Therefore, to help understanding, names of corresponding muscles used in other studies (Gadow, 1882; Ribbing, 1938; Cong et al., 1998) are indicated in Table 1. Similarly, corresponding muscle names in other studies are also indicated for lepidosaurs in Table 2, testudines in Table 3, and avians in Table 4, respectively.

Table 1.

Synonymy of crocodilian hindlimb muscles among four previous studies

| Standardized muscle name | Gadow (1882) | Ribbing (1938) | Cong et al. (1998) | Suzuki et al. (2011) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. tibialis cranialis | M. extensor longus digitorum | M. extensor digitorum communis | M. extensor digitorum longus, long head, or lateral head | M. extensor digitorum longus |

| M. extensor digitorum longus | M. tibialis anticus | M. extensor tarsi tibialis | M. extensor digitorum longus, short head, or medial head | M. tibialis anterior |

| M. peroneus longus | M. peroneus posterior, in part | M. extensor tarsi fibularis, in part | M. peroneus longus | M. peroneus longus |

| M. peroneus brevis | M. peroneus anterior | M. extensor tarsi fibularis, in part | M. peroneus brevis | M. peroneus brevis |

| M. adductor hallucis dorsalis | M. extensor hallucis proprius | M. extensores breves, in part | M. extensor hallucis longus | M. adductor hallucis dorsalis |

| M. extensor digitorum brevis | Nr. II α | M. extensores breves, in part | M. extensor hallucis brevis, in part | M. extensor digitorum I, II et III |

| Nr. II β | M. extensor digitorum brevis, in part (pars proximalis of digit II) | |||

| Nr. II γ | M. extensor digitorum brevis, in part (pars proximalis of digit III) | |||

| M. extensor hallucis brevis | Nr. IV α | M. extensores breves, in part | M. extensor hallucis brevis, in part | M. extensor hallucis brevis |

| M. extensor digiti II | Nr. IV β | M. extensores breves, in part | M. extensor digitorum brevis, in part | M. extensor digiti II |

| M. extensor digiti III | Nr. IV γ | M. extensores breves, in part | M. extensor digitorum brevis, in part | M. extensor digiti III |

| M. extensor digiti IV | Nr. III | M. extensores breves, in part | M. extensor digitorum brevis, in part | M. extensor digiti IV |

| M. interosseous dorsalis digiti II | Nr. V α | M. extensores breves, in part | Mm. interossei dorsales, in part (first slip) | M. interosseous dorsalis digiti II |

| M. interosseous dorsalis digiti III | Nr. V β | M. extensores breves, in part | Mm. interossei dorsales, in part (second slip) | M. interosseous dorsalis digiti III |

| M. interosseous dorsalis digiti IV | Nr. V γ | M. extensores breves, in part | – | M. interosseous dorsalis digiti IV |

| M. gastrocnemius | M. gastrocnemius, in part | M. gastrocnemius | M. gastrocnemius | M. gastrocnemius |

| M. flexor hallucis longus | M. gastrocnemius, in part | M. flexor profundus, in part | M. flexor hallucis longus | M. flexor digitorum longus |

| M. flexor digitorum longus | M. flexor longus digitorum | M. flexor profundus, in part | M. flexor digitorum longus | M. flexor hallucis longus |

| M. pronator profundus | M. tibialis‐posticus | M. pronator profundus | M. tibialis posterior | M. pronator profundus |

| M. interosseous cruris | M. flexor digiti quarti brevis | |||

| M. fibulocalcaneus | M. peroneus posterior, in part | M. flexor metatarsi V | M. pronator profundus | M. fibulocalcaneus |

| M. flexor digitorum brevis superficialis | Nr. VI | Mm. flexores breves superficiales | M. flexor digitorum brevis | M. flexor digitorum brevis superficialis |

| M. flexor digitorum brevis profundus | Nr. VII | M. flexor accesorius medialis | M. quadratus plantae | M. flexor digitorum brevis profundus |

| Mm. lumbricales | Nr. VIII, in part | M. flexor accesorius lateralis | Mm. lumbricales pedis, in part (superficial layer) | Mm. lumbricales |

| M. lumbricalis profundus | Nr. VIII, in part | Mm. contrahentes digitorum | Mm. lumbricales pedis, in part (deep layer) | M. lumbricalis profundus |

| M. flexor hallucis brevis | Nr. X β | Mm. flexores breves profundi, in part | M. flexor hallucis | M. flexor hallucis brevis superficialis |

| Nr. X α | M. abductor hallucis | M. flexor hallucis brevis profundus | ||

| M. adductor digiti V | – | – | – | – |

| Mm. contrahentes | Nr. X γ | Mm. flexores breves profundi, in part | Mm. interossei plantares, in part (first slip) | M. flexor digiti II |

| Nr. X δ | Mm. interossei dorsales, in part (pars plantares) | M. flexor digiti III | ||

| Nr. X ε | Mm. interossei plantares, in part (second slip) | M. flexor digiti IV | ||

| M. adductor hallucis plantaris | Nr. XI α | Mm. interdigitales, in part | M. adductor hallucis | M. adductor hallucis plantaris |

| M. interosseous plantaris digiti II | Nr. XI β | Mm. interdigitales, in part | Mm. interossei plantares, in part (first slip) | M. interosseous plantaris digiti II |

| M. interosseous plantaris digiti III | Nr. XI γ | Mm. interdigitales, in part | Mm. interossei plantares, in part (third slip) | M. interosseous plantaris digiti III |

| M. abductor digiti IV | Nr. XII | Mm. interdigitales, in part | M. abductor digiti quarti | M. abductor digiti IV dorsalis |

| M. abductor digiti IV plantaris |

Table 2.

Synonymy of lepidosaurian hindlimb muscles among three previous studies

| Standardized muscle name | Gadow (1882) | Ribbing (1938) | Russell and Bauer (2008) |

|---|---|---|---|

| M. tibialis cranialis | M. extensor longus digitorum | M. extensor digitorum communis | M. extensor digitorum longus |

| M. extensor digitorum longus | M. tibialis anticus | M. extensor tarsi tibialis | M. tibialis anterior |

| M. peroneus longus | M. peroneus posterior | M. extensor tarsi fibularis, in part | M. peroneus longus |

| M. peroneus brevis | M. peroneus anterior | M. extensor tarsi fibularis, in part | M. peroneus brevis |

| M. adductor hallucis dorsalis | M. extensor hallucis proprius | Mm. extensores breves, in part | M. adductor et extensor hallucis et indicus |

| M. extensor digitorum brevis | Nr. II | Mm. extensores breves, in part | Mm. extensores digitores breves, in part |

| M. extensor hallucis brevis | Nr. IV α, in part | Mm. extensores breves, in part | Mm. extensores digitores breves, in part |

| M. extensor digiti II | Nr. IV α, in part | Mm. extensores breves, in part | Mm. extensores digitores breves, in part |

| M. extensor digiti III | Nr. IV α, in part | Mm. extensores breves, in part | Mm. extensores digitores breves, in part |

| M. extensor digiti IV | Nr. III | Mm. extensores breves, in part | Mm. extensores digitores breves, in part |

| M. interosseous dorsalis digiti II | Nr. IV α, in part | – | Mm. extensores digitores breves, in part |

| M. interosseous dorsalis digiti III | Nr. IV α, in part | – | Mm. extensores digitores breves, in part |

| M. interosseous dorsalis digiti IV | Nr. IV α, in part | – | Mm. extensores digitores breves, in part |

| M. gastrocnemius | M. gastrocnemius, caput tibiale | M. gastrocnemius, internus | M. femorotibial gastrocnemius |

| M. gastrocnemius, caput femorale | M. gastrocnemius, externus | M. femoral gastrocnemius | |

| M. flexor hallucis longus | M. flexor longus digitorum, in part | M. flexor accessorius medialis | M. flexor digitorum longus, in part |

| M. flexor digitorum longus | M. flexor longus digitorum, in part | M. flexor profundus | M. flexor digitorum longus, in part |

| M. flexor digiti V | |||

| M. pronator profundus | M. tibialis posticus | M. pronator profundus | M. pronator profundus |

| M. fibulocalcaneus | – | M. flexor metatarsi V | M. abductor digiti quinti |

| M. flexor digitorum brevis superficialis | Nr. VI | Mm. flexores breves superficiales | Mm. flexores digitores breves |

| pfdl. calc. | |||

| M. flexor digitorum brevis profundus | Nr. VII, in part | M. flexor accessorius lateralis, in part | pfdl. met. 5 |

| Mm. lumbricales | – | Mm. flexores digitorum breves profundi | Mm. lumbricales |

| M. lumbricalis profundus | – | M. flexor accessorius lateralis, in part | pfdl. ap. |

| M. flexor hallucis brevis | Nr. X α | Mm. contrahentes digitorum, in part | M. flexor hallucis |

| M. adductor digiti V | – | – | M. adductor digiti quinti |

| Mm. contrahentes | Nr. X β–ε | Mm. contrahentes digitorum, in part | Mm. contrahentes |

| M. adductor hallucis plantaris | Nr. XI α | Mm. interdigitales, in part | Mm. interossei plantares, in part |

| M. interosseous plantaris digiti II | Nr. XI β | Mm. interdigitales, in part | Mm. interossei dorsales, in part |

| Mm. interossei plantares, in part | |||

| M. interosseous plantaris digiti III | Nr. XI γ | Mm. interdigitales, in part | Mm. interossei dorsales, in part |

| Mm. interossei plantares, in part | |||

| M. abductor digiti IV | Nr. IV β | – | Mm. extensores digitores breves, in part |

Table 3.

Synonymy of testudine hindlimb muscles among three previous studies

| Standardized muscle name | Gadow (1882) | Ribbing (1938) | Walker (1973) |

|---|---|---|---|

| M. tibialis cranialis | M. extensor longus digitorum | M. extensor digitorum communis | M. extensor digitorum communis |

| M. extensor digitorum longus | M. tibialis anticus | M. extensor tarsi tibialis | M. tibialis anterior |

| M. peroneus longus | M. peroneus anterior | M. extensor tarsi fibularis, in part | M. peroneus anterior |

| M. peroneus brevis | M. peroneus posterior | M. extensor tarsi fibularis, in part | M. peroneus posterior |

| M. adductor hallucis dorsalis | M. extensor hallucis proprius | Mm. extensores breves, in part | M. extensor hallucis proprius |

| M. extensor digitorum brevis | Nr. II | Mm. extensores breves, in part | Mm. extensores digitorum breves |

| Nr. VI | |||

| Nr. XI, in part | |||

| M. extensor hallucis brevis | Nr. XI, in part | Mm. extensores breves, in part | M. abductor hallucis |

| M. extensor digiti II | Nr. XI, in part | Mm. extensores breves, in part | Mm. interossei dorsales, in part |

| M. extensor digiti III | Nr. XI, in part | Mm. extensores breves, in part | Mm. interossei dorsales, in part |

| M. extensor digiti IV | Nr. XI, in part | Mm. extensores breves, in part | Mm. interossei dorsales, in part |

| M. interosseous dorsalis digiti II | Nr. XI, in part | Mm. extensores breves, in part | Mm. interossei dorsales, in part |

| M. interosseous dorsalis digiti III | Nr. XI, in part | Mm. extensores breves, in part | Mm. interossei dorsales, in part |

| M. interosseous dorsalis digiti IV | Nr. XI, in part | Mm. extensores breves, in part | Mm. interossei dorsales, in part |

| M. gastrocnemius | M. gastrocnemius | M. gastrocnemius | M. gastrocnemius |

| M. flexor hallucis longus | M. flexor longus digitorum, in part | M. flexor profundus, in part | M. flexor digitorum longus, in part |

| M. flexor digitorum longus | M. flexor longus digitorum, in part | M. flexor profundus, in part | M. flexor digitorum longus, in part |

| M. flexor accessorius lateralis | |||

| M. pronator profundus | M. tibialis posticus | M. pronator profundus, in part | M. pronator profundus |

| M. fibulocalcaneus | – | – | – |

| M. flexor digitorum brevis superficialis | – | – | Plantar aponeurosis |

| M. flexor digitorum brevis profundus | – | – | – |

| Mm. lumbricales | Nr. VII, in part | Mm. flexores breves superficiales, in part | M. flexor digitorum communis sublimis |

| Nr. VIII, in part | |||

| M. lumbricalis profundus | Nr. VII, in part | Mm. flexores breves superficiales, in part | Mm. lumbricales |

| Nr. VIII, in part | |||

| M. flexor hallucis brevis | Nr. XI, in part | Mm. flexores breves profundi, in part | Mm. interossei plantares, in part |

| M. adductor digiti V | – | – | – |

| Mm. contrahentes | Nr. XI, in part | Mm. flexores breves profundi, in part | Mm. interossei plantares, in part |

| M. contrahentes digitorum | |||

| M. adductor hallucis plantaris | Nr. XI, in part | Mm. interdigitales, in part | Mm. interossei plantares, in part |

| M. interosseous plantaris digiti II | Nr. XI, in part | Mm. interdigitales, in part | Mm. interossei plantares, in part |

| M. interosseous plantaris digiti III | Nr. XI, in part | Mm. interdigitales, in part | Mm. interossei plantares, in part |

| M. abductor digiti IV | Nr. XI, in part | Mm. interdigitales, in part | Mm. interossei plantares, in part |

Table 4.

Synonymy of avian hindlimb muscles among three previous studies

| Standardized muscle name | Fujioka (1962) | Vanden Berge (1975) | Vanden Berge and Zweers (1993) |

|---|---|---|---|

| M. tibialis cranialis | M. tibialis anterior | M. tibialis cranialis | M. tibialis cranialis |

| M. extensor digitorum longus | M. extensor digitorum longus | M. extensor digitorum longus | M. extensor digitorum longus |

| M. peroneus longus | M. peroneus longus | M. fibularis (peroneus) longus | M. fibularis (peroneus) longus |

| M. peroneus brevis | M. peroneus brevis | M. fibularis (peroneus) brevis | M. fibularis (peroneus) brevis |

| M. adductor hallucis dorsalis | – | – | – |

| M. extensor digitorum brevis | – | – | – |

| M. extensor hallucis brevis | M. extensor hallucis longus | M. extensor hallucis longus | M. extensor hallucis longus |

| M. extensor digiti II | – | – | – |

| M. extensor digiti III | M. extensor digiti terti | M. extensor brevis digiti III | M. extensor brevis digiti III |

| M. extensor digiti IV | – | – | – |

| M. interosseous dorsalis digiti II | M. abductor digiti secundi | M. abductor (extensor) digiti II | M. abductor digiti II |

| M. interosseous dorsalis digiti III | – | – | – |

| M. interosseous dorsalis digiti IV | M. adductor digiti quarti | M. extensor brevis digiti IV | M. extensor brevis digiti IV |

| M. gastrocnemius | M. gastrocnemius | M. gastrocnemius | M. gastrocnemius |

| M. flexor hallucis longus | M. flexor hallucls longus | M. flexor hallucis longus | M. flexor hallucis longus |

| M. flexor perforans et perforatus digiti secundi | M. flexor perforans et perforatus digiti II | M. flexor perforans et perforatus digiti II | |

| M. flexor perforans et perforatus digiti tertii | M. flexor perforans et perforatus digiti III | M. flexor perforans et perforatus digiti III | |

| M. flexor perforatus digiti secundi | M. flexor perforatus digiti II | M. flexor perforatus digiti II | |

| M. flexor perforatus digiti terti | M. flexor perforatus digiti III | M. flexor perforatus digiti III | |

| M. flexor perforatus digiti quarti | M. flexor perforatus digiti IV | M. flexor perforatus digiti IV | |

| M. flexor digitorum longus | M. flexor perforans digitorum profundus | M. flexor digitorum longus | M. flexor digitorum longus |

| M. tibialis posterior | M. plantaris | M. plantaris | |

| M. pronator profundus | – | – | – |

| M. fibulocalcaneus | – | – | – |

| M. flexor digitorum brevis superficialis | – | – | – |

| M. flexor digitorum brevis profundus | – | – | – |

| Mm. lumbricales | – | – | – |

| M. lumbricalis profundus | – | M. lumbricalis | M. lumbricalis |

| M. flexor hallucis brevis | – | – | – |

| M. adductor digiti V | – | – | – |

| Mm. contrahentes | – | – | – |

| M. adductor hallucis plantaris | M. flexor hallucis brevis | M. flexor hallucis brevis | M. flexor hallucis brevis |

| M. interosseous plantaris digiti II | M. adductor digiti secundi | M. adductor digiti II | M. adductor digiti II |

| M. interosseous plantaris digiti III | – | – | – |

| M. abductor digiti IV | M. abductor digiti quarti | M. abductor digiti IV | M. abductor digiti IV |

To assess the muscle homology, the innervation pattern has often been considered as the most significant criterion. It is because that the nerve‐muscle specificity has been assumed to be more conservative phylogenetically than are other criteria, namely, the morphology and positions of muscle attachment sites and their mechanical functions. However, Straus (1946) reviewed this concept of nerve‐muscle specificity and concluded that resemblances in the innervation pattern across taxa merely result from general similarity in the development pattern, rather than reflecting any inherent and immutable connection between the muscle and nerve. Actually, some topologically similar pedal muscles with similar mechanical functions have also been found to have different innervation patterns (Russell and Bauer, 2008). For example, the detailed innervation patterns are often inconsistent among studies on crocodilians. One muscle, m. tibialis cranialis, whose homology among crocodilians is broadly accepted, is innervated by both n. peroneus superficialis and n. peroneus profundus according to Gadow (1882) but only by n. peroneus profundus according to Cong et al. (1998) and Suzuki et al. (2011). As another example, the distal portions of both fibular nerves form a loop, which gives rise to the branch supplying m. interosseous dorsalis digiti III in crocodilians (Gadow, 1882; S. Hattori, pers. obs.). In such a loop, it is difficult to assess which nerve is dominant one contributing to the branch. In these cases, therefore, muscles with different innervation patterns are not necessarily non‐homologous (Cunningham, 1881; Gadow, 1882). Accordingly, the innervation patterns were not used as the exclusive, primary criterion for the muscle homology in the present study. Instead, the congruence among the innervation patterns, the morphology and positions of attachment sites of muscles and similarities of their mechanical functions was regarded as the strongest evidence for the homology.

3. RESULTS

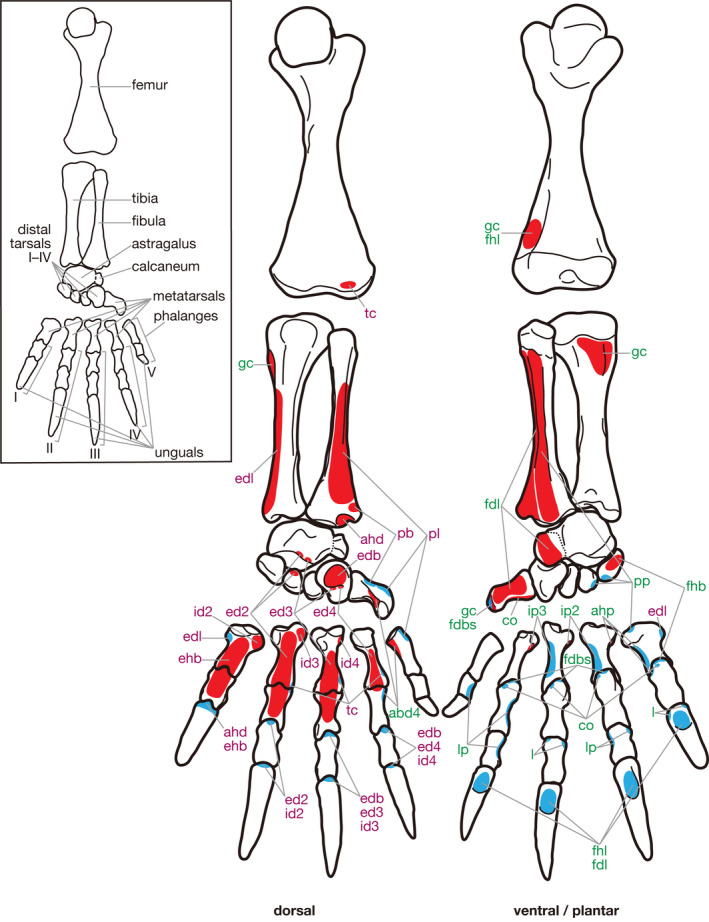

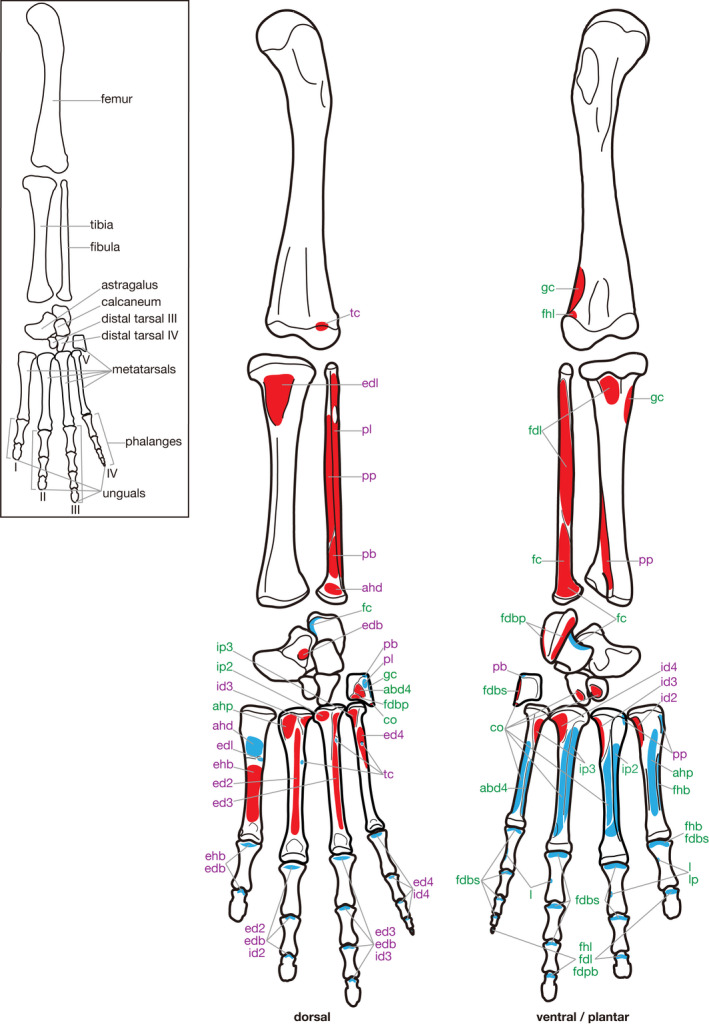

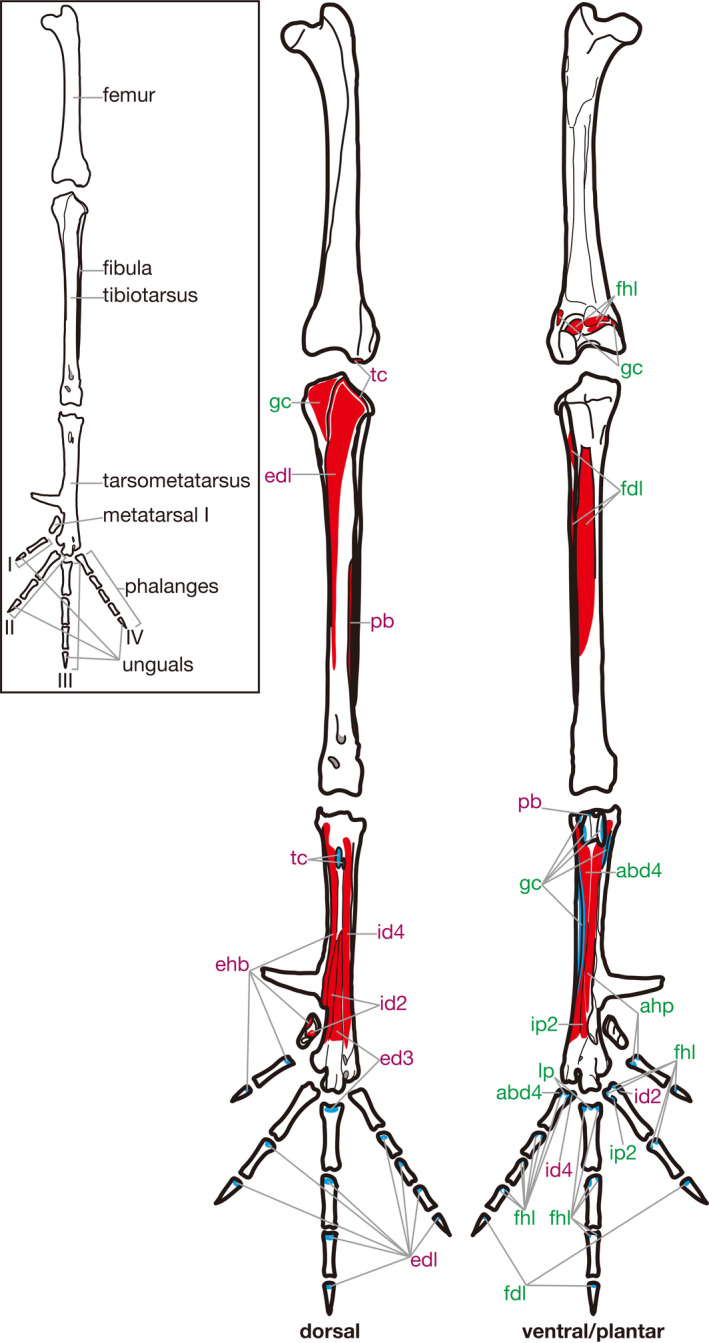

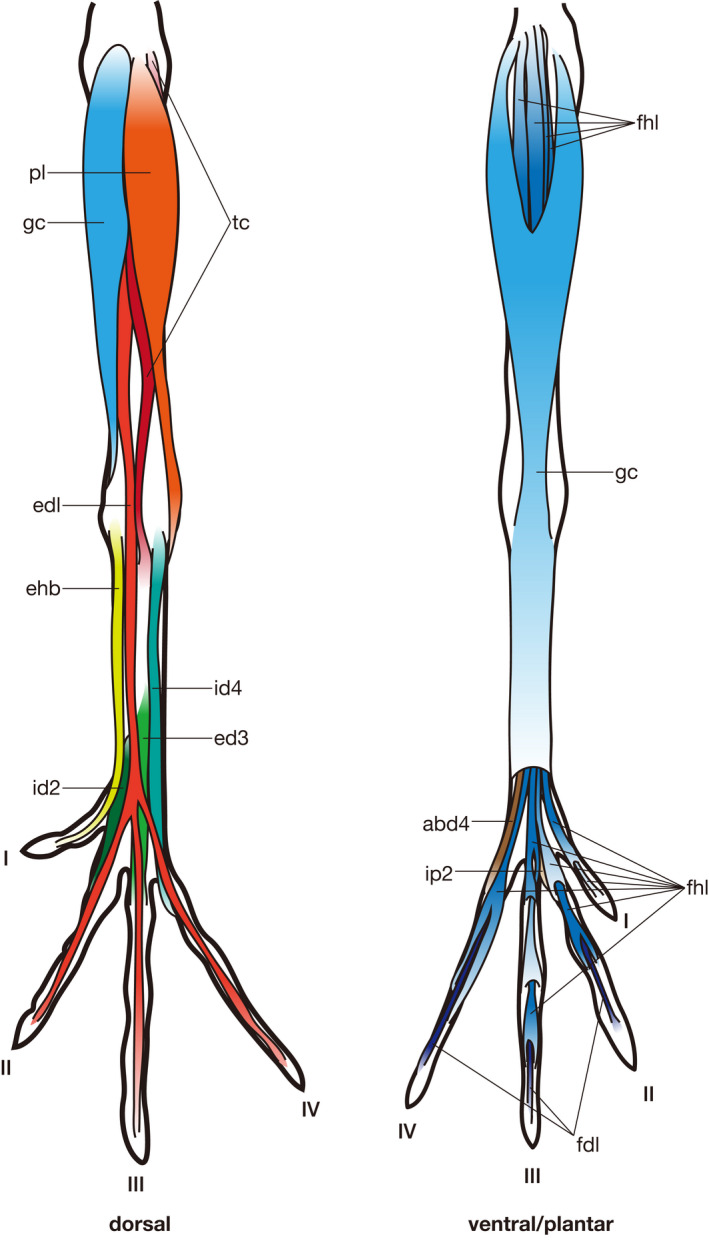

In the following section, the morphology of putatively homologous muscles across sauropsid clades is described under each heading of the proposed standardized muscle name. In order to clearly distinguish results of our first‐hand dissections and observations and descriptions cited from previous studies in the following descriptions, the former are provided in the past tense, whereas the latter are in the present tense followed by citations. Attachments on bones and superficial morphology of the described muscles are illustrated in figures: Figures 2 and 3 for Lepidodsauria, Figures 4 and 5 for Testudines, Figures 6 and 7 for Crocodilia, and Figures 8 and 9 for Aves. Homologies of muscles proposed in the present study were summarized in Table 5. Osteological correlates were recognized in more than 80% of examined muscles and were summarized in Table 6. Although the morphology of these muscles and associated osteological correlates were almost the same within each clade, there were a few differences recognized in this study as described below.

Figure 2.

Hindlimb skeleton and attachment sites of pedal muscles in Iguana iguana. Muscle origins and insertions are indicated in red and blue, respectively. Names of dorsal and ventral/plantar muscles are indicated in purple and green, respectively. See Table 5 for abbreviations

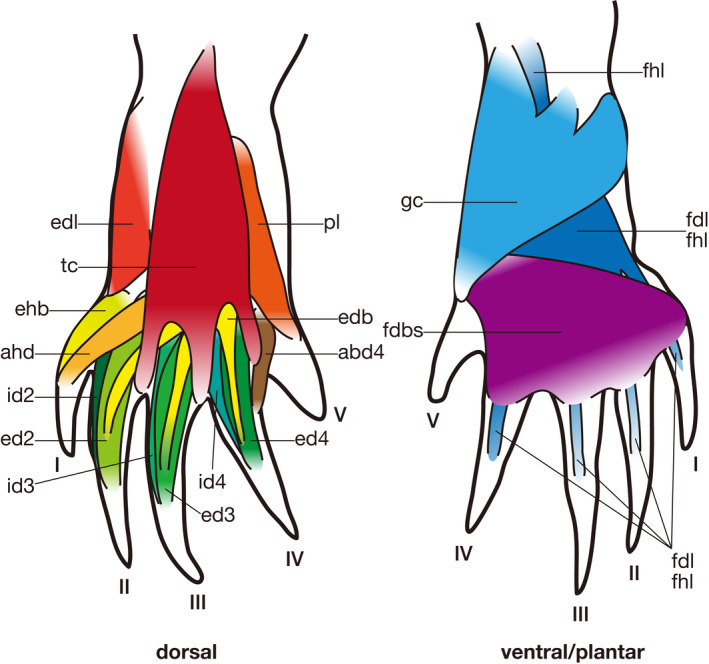

Figure 3.

Semi‐schematic illustrations of the pedal muscles of Iguana iguana (modified after Russell and Bauer, 2008). Some muscles are omitted for simplicity. See Table 5 for abbreviations

Figure 4.

Hindlimb skeleton and attachment sites of pedal muscles in Chelydra serpentina. Muscle origins and insertions are indicated in red and blue, respectively. Names of dorsal and ventral/plantar muscles are indicated in purple and green, respectively. See Table 5 for abbreviations

Figure 5.

Semi‐schematic illustrations of the pedal muscles of Chelydra serpentina (modified after Walker, 1973). Some muscles are omitted for simplicity. See Table 5 for abbreviations

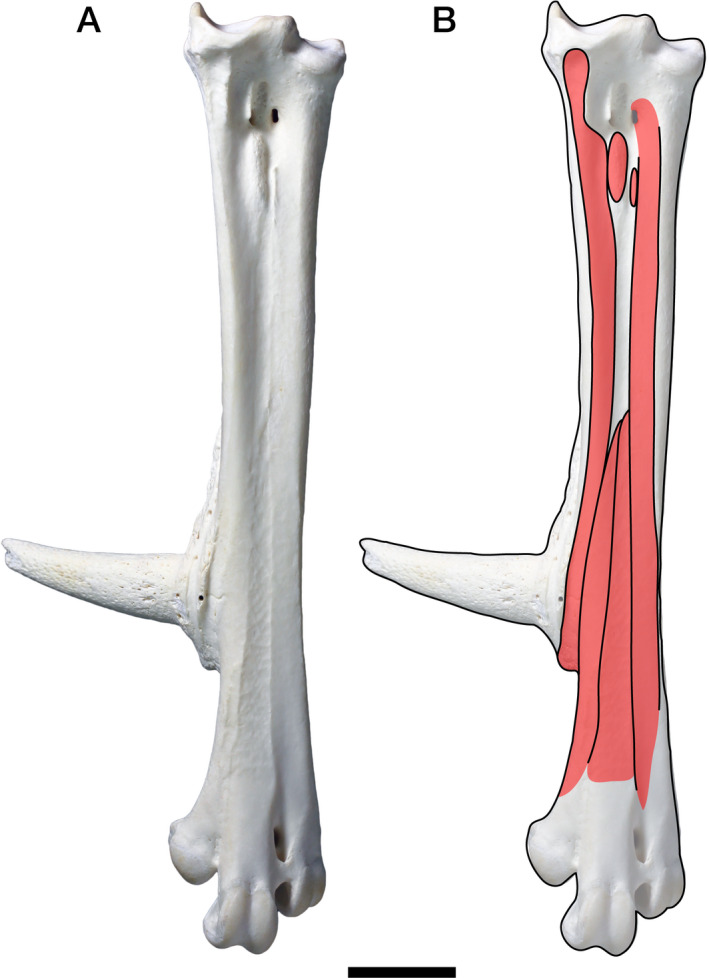

Figure 6.

Hindlimb skeleton and attachment sites of pedal muscles in Paleosuchus palpebrosus. Muscle origins and insertions are indicated in red and blue, respectively. Names of dorsal and ventral/plantar muscles are indicated in purple and green, respectively. See Table 5 for abbreviations

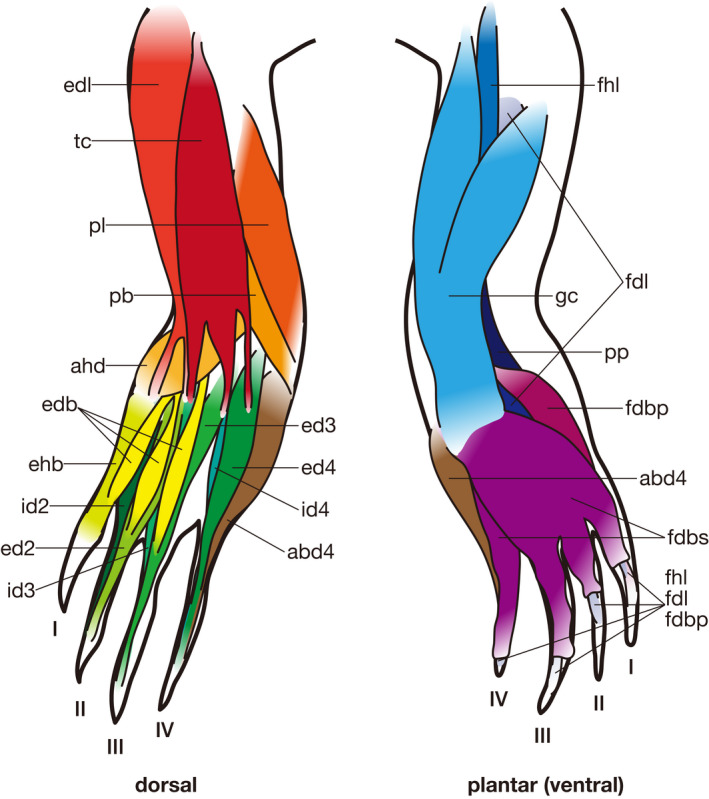

Figure 7.

Pedal muscles of Paleosuchus palpebrosus (modified after Ribbing, 1938). Some muscles are omitted for simplicity. See Table 5 for abbreviations

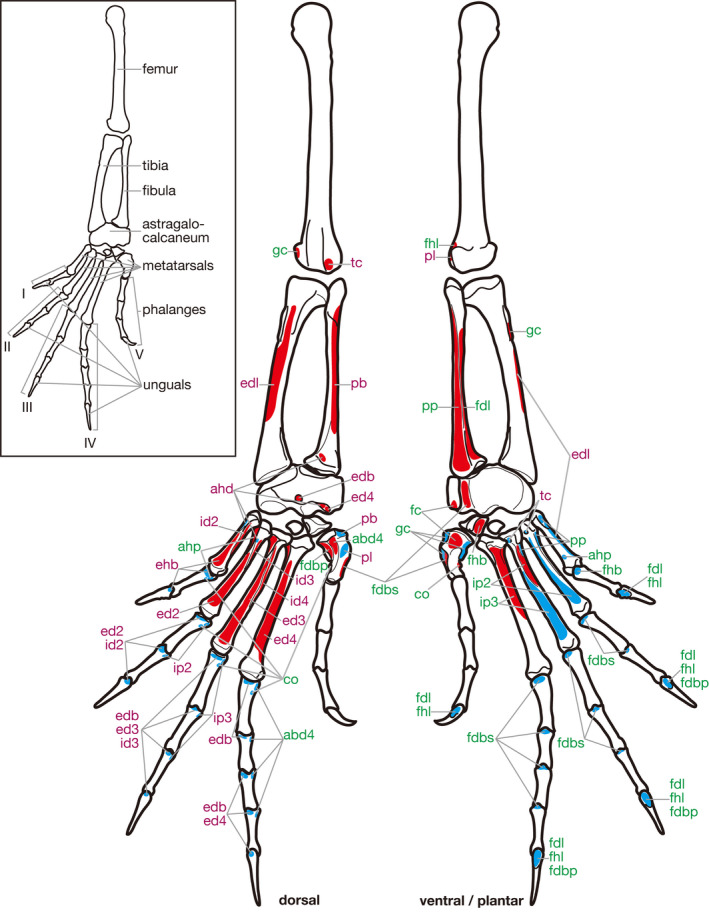

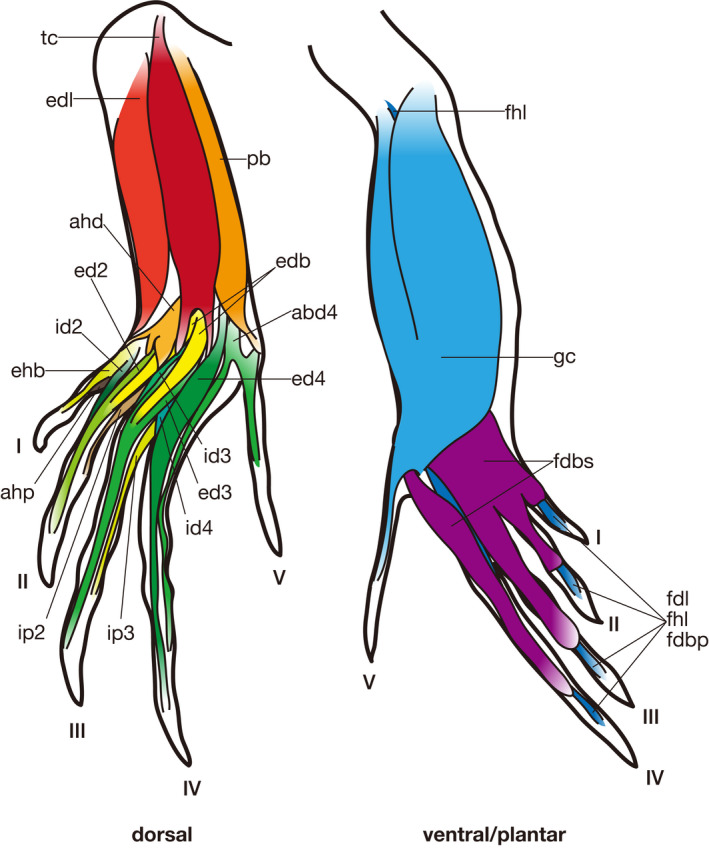

Figure 8.

Hindlimb skeleton and attachment sites of pedal muscles in Gallus gallus. Muscle origins and insertions are indicated in red and blue, respectively. Names of dorsal and ventral/plantar muscles are indicated in purple and green, respectively. See Table 5 for abbreviations

Figure 9.

Pedal muscles of Gallus gallus (modified after Yasuda, 2002). Some muscles are omitted for simplicity. See Table 5 for abbreviations

Table 5.

Muscle homology and nomenclature adopted in the present study

| Standardized muscle name | Abbreviation | Lepidosauria (Russell and Bauer, 2008) | Testudines (Walker, 1973) | Crocodilia (Suzuki et al., 2011) | Aves (Vanden Berge and Zweers, 1993) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. tibialis cranialis | tc | M. extensor digitorum longus | M. extensor digitorum communis | M. extensor digitorum longus | M. tibialis cranialis |

| M. extensor digitorum longus | edl | M. tibialis anterior | M. tibialis anterior | M. tibialis anterior | M. extensor digitorum longus |

| M. peroneus longus | pl | M. peroneus longus | M. peroneus anterior | M. peroneus longus | M. fibularis longus |

| M. peroneus brevis | pb | M. peroneus brevis | M. peroneus posterior | M. peroneus brevis | M. fibularis brevis |

| M. adductor hallucis dorsalis | ahd | M. adductor et extensor hallucis et indicus | M. extensor hallucis proprius | M. adductor hallucis dorsalis | |

| M. extensor digitorum brevis | edb | Mm. extensores digitores breves (2, 3), in part | Mm. extensores digitorum breves | M. extensor digitorum I, II, et III | |

| M. extensor hallucis brevis | ehb | Mm. extensores digitores breves (1) | M. abductor hallucis | M. extensor hallucis brevis | M. extensor hallucis longus |

| M. extensor digiti II | ed2 | Mm. extensores digitores breves (2), in part | Mm. interossei dorsales, in part | M. extensor digiti II | |

| M. extensor digiti III | ed3 | Mm. extensores digitores breves (3), in part | Mm. interossei dorsales, in part | M. extensor digiti III | M. extensor brevis digiti III |

| M. extensor digiti IV | ed4 | Mm. extensores digitores breves (4), in part | Mm. interossei dorsales, in part | M. extensor digiti IV | |

| M. interosseous dorsalis digiti II | id2 | Mm. extensores digitores breves (2), in part | Mm. interossei dorsales, in part | M. interosseous dorsalis digiti II | M. abductor digiti II |

| M. interosseous dorsalis digiti III | id3 | Mm. extensores digitores breves (3), in part | Mm. interossei dorsales, in part | M. interosseous dorsalis digiti III | |

| M. interosseous dorsalis digiti IV | id4 | Mm. extensores digitores breves (4), in part | Mm. interossei dorsales, in part | M. interosseous dorsalis digiti IV | M. extensor brevis digiti IV |

| M. gastrocnemius | gc | M. gastrocnemius | M. gastrocnemius | M. gastrocnemius | M. gastrocnemius |

| M. flexor hallucis longus | fhl | M. flexor digitorum longus (femoral head) | M. flexor digitorum longus, in part | M. flexor digitorum longus |

M. flexor hallucis longus M. flexor perforatus digiti II M. flexor perforatus digiti III M. flexor perforatus digiti IV M. flexor perforans et perforatus digiti II M. flexor perforans et perforatus digiti III |

| M. flexor digitorum longus | fdl | M. flexor digitorum longus (fibular head) | M. flexor digitorum longus, in part | M. flexor hallucis longus |

M. flexor digitorum longus M. plantaris |

| M. pronator profundus | pp | M. pronator profundus | M. pronator profundus | M. pronator profundus | |

| M. fibulocalcaneous | fc | M. abductor digiti quinti | M. fibulocalcaneous | ||

| M. flexor digitorum brevis superficialis | fdbs | M. flexores digitores breves +pfdl. calc. | Plantar aponeurosis | M. flexor digitorum brevis superficialis | |

| M. flexor digitorum brevis profundus | fdbp | pfdl. met. 5 | M. flexor digitorum brevis profundus | ||

| Mm. lumbricales | l | Mm. lumbricales | M. flexor digitorum communis sublimis | Mm. lumbricales | |

| M. lumbricalis profundus | lp | pfdl. ap. | Mm. lumbricales | M. lumbricalis profundus | M. lumbricalis |

| M. flexor hallucis brevis | fhb | M. flexor hallucis | Mm. interossei plantares, in part |

M. flexor hallucis brevis superficialis M. flexor hallucis brevis profundus |

|

| M. adductor digiti V | add5 | M. adductor digiti quinti | |||

| Mm. contrahentes | co | Mm. contrahentes | Mm. interossei plantares, in part |

M. flexor digiti II M. flexor digiti III M. flexor digiti IV |

|

| M. adductor hallucis plantaris | ahp | Mm. interossei plantales (1) | Mm. interossei plantares, in part | M. adductor hallucis plantaris | M. flexor hallucis brevis |

| M. interosseous plantaris digiti II | ip2 |

Mm. interossei dorsales, in part Mm. interossei plantares (2) |

Mm. interossei plantares, in part | M. interosseous plantaris digiti II | M. adductor digiti II |

| M. interosseous plantaris digiti III | ip3 |

Mm. interossei dorsales, in part Mm. interossei plantares (3) |

Mm. interossei plantares, in part | M. interosseous plantaris digiti III | |

| M. abductor digiti IV | abd4 | Mm. extensores digitores breves (5) | Mm. interossei plantares, in part |

M. abductor digiti IV dorsalis M. abductor digiti IV plantaris |

M. abductor digiti IV |

Arabic numerals in parentheses indicate the digits on which each muscle acts.

Table 6.

List of osteological correlates of the origin and insertion of each muscle observed in the present study

| Standardized muscle name | Origin/Insertion | Lepidosauria | Testudines | Crocodilia | Aves |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. tibialis cranialis | Origin | Absent | Absent | Absent | The lateral expansion of the cranial cnemial crest and the dorsoventral expansion of the lateral cnemial crest |

| Insertion | A tubercle on each lateroplantar aspect of MTs II & III | A laterodorsal surface of each distal shaft of MTs I–IV | A tubercle on the medial margin of each proximal shaft of MTs II–IV | Tubercles on the dorsal aspect of the proximal tarsometatarsus (tuberositas m. tibialis cranialis) | |

| M. extensor digitorum longus | Origin | Absent | A rugose longitudinal sulcus on the dorsomedial margin of the tibia | A rugose surface on the proximal‐most portion of the dorsal aspect of the tibia | A broad surface between the cranial and the lateral cnemial crests |

| Insertion | Absent | A tubercle on the proximomedial end of MT I | A bulge on each dorsal aspect of MTs I and II | The proximodorsal lip of each phalanx of digits II–IV except proximal‐most phalanges | |

| M. peroneus longus | Origin | Absent | A slightly excavated dorsal surface on the distal half of the fibula | A laterodorsal surface of the fibula, between each longitudinal ridge on the dorsal and the lateral aspects of the shaft | Proximal margins of the cranial and the lateral cnemial crests |

| Insertion | A depression on the dorsolateral aspect of MT V | Absent | A flat surface on the proximolateral margin of MT V | Absent | |

| M. peroneus brevis | Origin | Absent | Absent | A flat laterodorsal surface on the distal two thirds of the fibular shaft | A laterodorsal surface of the distal two thirds of the tibial shaft and a dorsal surface of the distal half of the fibular shaft |

| Insertion | A process on the proximolateral margin of MT V (outer process) | Absent | Absent | A proximal surface near the lateral margin of the hypotarsus (tuberculum m. fibularis brevis) | |

| M. adductor hallucis dorsalis | Origin | A dorsolateral surface of the distal end of the fibula and the medial half of the proximolateral lip of the tarsal facet of the astragalocalcaneum | A depression on the distodorsal margin of the tibia | Absent | NA |

| Insertion | Absent | Absent | Absent | NA | |

| M. extensor digitorum brevis | Origin | A depression on the dorsal aspect of astragalocalcaneum | A depression on the dorsal aspect of DT IV | A depression on the dorsal aspect of the astragalus | NA |

| Insertion | The proximodorsal lip of each phalanx of digits III and IV (as well as digits I and II in some taxa) | The proximodorsal lip of each phalanx of digits III and IV | The proximodorsal lip of each phalanx of digits I–III | NA | |

|

M. extensor hallucis brevis |

Origin | Absent | Absent | The dorsal aspect of MT I, distal to the transverse ridge | Longitudinal depressions on the medial parts of the dorsal aspects of the tarsometatarsus and MT I |

| Insertion | The proximodorsal lip of each phalanx of digit I | The proximodorsal lip of I−2 | The proximodorsal lip of each phalanx of digit I | The proximodorsal lip of each phalanx of digit I | |

| M. extensor digiti II | Origin | Absent | Absent | Absent | NA |

| Insertion | The proximodorsal lip of each phalanx of digit II | The proximodorsal lip of each of II−2 and 3 | The proximodorsal lip of each phalanx of digit II | NA | |

| M. extensor digiti III | Origin | Absent | Absent | Absent | A slightly depressed rugose surface on the dorsal aspect of the distal half of the tarsometatarsus |

| Insertion | The proximodorsal lip of each phalanx of digit III | The proximodorsal lip of each of III−2, 3, and 4 | The proximodorsal lip of each phalanx of digit III | The proximodorsal lip of III−1 | |

| M. extensor digiti IV | Origin | Lateral half of the proximolateral lip of the tarsal facet of the astragalocalcaneum | Absent | Absent | NA |

| insertion | The proximodorsal lip of each of IV−2, 3, 4 and 5 | The proximodorsal lip of each of IV−2, 3, 4 and 5 | The proximodorsal lip of each phalanx of digit IV | NA | |

|

M. interosseous dorsalis digiti II |

Origin | A longitudinal rugosity along the lateral margin of MT I | A rugosity on the proximomedial margin of the dorsal aspect of MT I | A depression on the lateroplantar aspect of MT I | An oblique groove on the medial aspect of the tarsometatarsus and the fossa metatarsi I |

| Insertion | The proximodorsal lip of each phalanx of digit II | The proximodorsal lip of each phalanx of digit II | The proximodorsal lip of II−1 | A medioplantar tubercle on the proximal end of II−1 | |

| M. interosseous dorsalis digiti III | Origin | A longitudinal rugosity along the lateral margin of the proximal half of MT II | A rugosity on the proximomedial margin of the dorsal aspect of MT II | A rugosity on the proximolateral margin of each of dorsal and lateral aspects of MT II | NA |

| Insertion | The proximodorsal lip of each phalanx of digit III | The proximodorsal lip of each of III−2, 3, and 4 | The proximodorsal lip of III−1 | NA | |

| M. interosseous dorsalis digiti IV | Origin | A longitudinal rugosity on the lateral margin of the proximal half of MT III | A rugosity on the proximomedial margin of the dorsal aspect of MT III | A depression on the lateroplantar aspect of the proximal shaft of MT III | A sulcus laterally along the origin of m. extensor brevis digiti III |

| Insertion | The proximodorsal lip of each pahalnx of digit IV | The proximodorsal lip of each of IV−2 and 3 | The proximodorsal lip of IV−1 | A tuber on the medial aspect of IV−1 | |

| M. gastrocnemius | Origin | The medial and the lateral femoral epicondyles and distal portion of the tibial ventral crest | A rugose swelling on the medial margin of the dorsal aspect of the tibia, a blunt depression on the ventral aspect of the proximal tibia, and a depression on the lateroventral aspect of the distal femur | A depression on the lateroventral margin of the distal‐most portion of the shaft of the femur | A rugose depression on the lateroventral margin of the distal‐most portion of the femoral shaft, a shallow depression just proximal to the medial distal condyle of the femur, and the medial aspect of the cranial cnemial crest of the tibia |

| Insertion | The medial and the lateral plantar tubercles of MT V | A prominent tubercle on the lateral margin of the plantar aspect of MT V | The lateral flange of MT V | Longitudinal ridges on the medial and lateral margins of the plantar aspect of the hypotarsus and the tarsometatarsal shaft | |

| M. flexor hallucis longus | Origin | Absent | A shallow and broad depression on the lateroventral aspect of the femur | Absent | Several facets on the distal end of the fossa poplitea of the femur |

| Insertion | The flexor tubercle of each ungual of digits II–IV | The flexor tubercle of each ungual of digits I–IV | The flexor tubercle of each ungual of digits I–IV | The flexor tubercle of I−2 and the proximoplantar heel of each non‐ungual phalanx of digits II–IV | |

| M. flexor digitorum longus | Origin | A depression on the medial aspect of the fibula, just distal to the fibular attachment of m. popliteus | A distinct surface between the lateral margin of the shaft and the longitudinal ridge situated laterally on the ventral aspect of the fibula | A flat surface on the ventral aspect of the fibula, and depression on the ventral aspect of the proximal‐most tibial shaft | A flat surface on the dorsal aspect of the proximal one third and the lateral and ventral aspects of the distal two thirds of the fibular shaft |

| Insertion | The flexor tubercle of each ungual of digits II–IV | The flexor tubercle of each ungual of digits I–IV | The flexor tubercle of each ungual of digits I–IV | The flexor tubercle of each ungual of digits II–IV | |

| M. pronator profundus | Origin | A flat surface on the ventral aspect of fibula | A flat surface between two longitudinal ridges on the ventral aspect of the fibular shaft | A flat surface between longitudinal stout ridges on the dorsolateral and lateral margins on the ventral aspect of the tibial shaft | NA |

| Insertion | Rugose surfaces or swellings on the proximomedial margins of the plantar aspects of MTs I–III | Absent | Narrow and rugose swelling on the proximomedial margin of the plantar aspect of MT I | NA | |

| M. fibulocalcaneous | Origin | A smooth surface on the plantar aspect of the calcaneal tuber | NA | A flat surface on the ventral aspect of the distal one third of the fibula | NA |

| Insertion | Absent | NA | The dorsal surface of the calcaneal tuber | NA | |

| M. flexor digitorum brevis superficialis | Origin | Absent | Absent | Longitudinal ridge or bulge on the lateroplantar margin of MT V | NA |

| Insertion | The proximoplantar heel of each non‐ungual phalanx of digits I–IV | The proximoplantar heel of each of II−1, III−1, and IV−1 | The proximoplantar heel of each non‐ungual phalanx of digits I–III | NA | |

| M. flexor digitorum brevis profundus | Origin | A concavity on the medial aspect of MT V | NA | Medial and lateral margins of the calcaneal tuber and the concavity on the distomedial margin of the plantar aspect of MT V | NA |

| Insertion | The flexor tubercle of each ungual of digits I–IV | NA | The flexor tubercle of the unguals of digits I–III | NA | |

| Mm. lumbricales | Origin | Absent | Absent | Absent | NA |

| Insertion | The proximoplantar heel of each non‐ungual phalanx of digits III and IV | Absent | Absent | NA | |

| M. lumbricalis profundus | Origin | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Insertion | The proximoplantar heel of each of II−1, III−1, and IV−1 | Absent | Absent | Absent | |

| M. flexor hallucis brevis | Origin | The plantar tubercle of DT IV | A depression on the plantar aspect of DT I | Absent | NA |

| Insertion | The proximoplantar heel of I−1 | The proximoplantar heel of I−1 | The longitudinal depression on the planter surface of MT I and the proximoplantar heel of I−1 | NA | |

| M. adductor digiti V | Origin | Absent | NA | NA | NA |

| Insertion | Absent | NA | NA | NA | |

| Mm. contrahentes | Origin | A small tubercle on the medial margin of the shaft of MT V | Absent | A depression on each plantar aspect of DTs III and IV and a tubercle on the distal end of MT V | NA |

| Insertion | Absent | Absent | The medioplantar surface of each of MTs II, III, and IV | NA | |

| M. adductor hallucis plantaris | Origin | The dorsomedial surface of the proximal shaft of MT II | A depression on the medial aspect of the proximal portion of MT II | A depression on the mediodorsal aspect of near the proximal end of MT II | The medial part of the sulcus flexorius of the tarsometatarsus |

| Insertion | Absent | Absent | A broad, shallow depression on the plantar aspect of MT I | The proximoplantar heel of I‐1 | |

| M. interosseous plantaris digiti II | Origin | The dorsomedial and medioplantar surfaces of the proximal shaft of MTIII | A depression on the medial aspect of MT III | Depressions on the dorsomedial and medioplantar aspects of near the proximal end of MT III | The central part of the distal sulcus flexorius |

| Insertion | The lateroplantar surface MT II | Absent | The lateroplantar surface of MT II | A small tubercle on the lateroplantar margin of the proximal end of II−1 | |

| M. interosseous plantaris digiti III | Origin | The medial and the plantar surfaces of proximal two thirds of MT IV | A depression on the medial aspect of MT IV | Depressions on the dorsomedial and medioplantar aspects near the proximal end of MT IV | NA |

| Insertion | The lateroplantar surface of MT III | Absent | The lateroplantar surface of MT III | NA | |

| M. abductor digiti IV | Origin | The dorsomedial surface of MT V | A depression on the distal aspect of the medial portion of MT V | The mediodistal margin of the dorsal aspect of MT V | The lateral portion of the sulcus flexorius |

| Insertion | Absent | Absent | A flat surface between the plantar ridge and the medial margin of MT IV | A tubercle projecting plantarly on the lateroproximal margin of IV−1 |

NA indicates the absence of the muscle itself.

3.1. Dorsal Musculature

3.1.1. Musculus tibialis cranialis

Lepidosauria: M. extensor digitorum longus (Russell and Bauer, 2008)

Testudines: M. extensor digitorum communis (Walker, 1973)

Crocodilia: M. extensor digitorum longus (Suzuki et al., 2011)

Aves: M. tibialis cranialis (Vanden Berge and Zweers, 1993)

Lepidosauria: In the dissected specimens of Iguana and Varanus, m. extensor digitorum longus arose from the dorsomedial aspect of the lateral distal condyle of the femur and inserted on the metatarsals (MTs) II and III by two tendons, as described by Russell and Bauer (2008). Each insertion tendon passed the lateral aspect of the proximal shaft of each of MTs II and III, and inserted on the tubercle on its lateroplantar aspect. It was innervated by the fibular nerve.

Testudines: In the examined specimen of Chelydra, m. extensor digitorum communis arose from the dorsal aspect of the lateral distal condyle of the femur and inserted on the lateral sides of MTs I–IV and the proximodorsal lip of I‐2, as seen in Emys (Ribbing, 1938). Among testudines, there are some variations in the insertion site. For example, Gadow (1882) described that this muscle inserts on the proximal phalanges of digits I–IV. This muscle is innervated by the fibular nerve (Walker, 1973).

Crocodilia: In the examined specimens of Paleosuchus and Crocodylus, m. extensor digitorum longus arose from the dorsal aspect of the femur, just proximal to the lateral distal condyle, as described in previous studies (Gadow, 1882; Cong et al., 1998; Suzuki et al., 2011). It inserted on the tubercle on the medial margin of each proximal shaft of MTs II–IV, whereas an additional insertion on MT I is reported by Gadow (1882), Ribbing (1909, 1938) and Cong et al. (1998). On the medial‐most insertion site, the muscle merged with m. tibialis anterior as described by Suzuki et al. (2011). This muscle is innervated by the fibular nerve (Gadow, 1882; Ribbing, 1909, 1938; Cong et al., 1998; Suzuki et al., 2011).

Aves: In the dissected specimens of Gallus and Grus, m. tibialis cranialis took the origin on the distal extremity of the lateral distal condyle of the femur (fovea tendinis m. tibialis cranialis; Vanden Berge and Zweers, 1993) and the cranial and lateral cnemial crests of the tibia (Fujioka, 1962; Vanden Berge, 1975). The tibial origins were on the lateral expansion of the cranial cnemial crest and the dorsoventral expansion of the lateral cnemial crest. This muscle inserted on the tubercles on the dorsal aspect of the proximal tarsometatarsus (tuberositas m. tibialis cranialis; Vanden Berge and Zweers, 1993). It is innervated by the common fibular nerve (Vanden Berge, 1975).

Comparison: Except for the additional origin on the proximal extremity of the tibia in avians, the sites of origin on the femur are conserved among sauropsids. The general innervation pattern also remains conservative. The insertion is generally on MTs II and III, although additional insertions are variably present. The insertion scar on the dorsal aspect of the tarsometatarsus in avians, the tuberositas m. tibialis cranialis, appears to have been originally situated on MTs II and III before the fusion among MTs. Although the name meaning a digital extensor is commonly used for this muscle in non‐avian sauropsids, the avian name m. tibialis cranialis is used to indicate this and all other sauropsid homologues in the following discussion.

3.1.2. Musculus extensor digitorum longus

Lepidosauria: M. tibialis anterior (Russell and Bauer, 2008)

Testudines: M. tibialis anterior (Walker, 1973)

Crocodilia: M. tibialis anterior (Suzuki et al., 2011)

Aves: M. extensor digitorum longus (Vanden Berge and Zweers, 1993)

Lepidosauria: In the dissected specimens of Iguana and Varanus, m. tibialis anterior took the origin from the broad area on the shaft of the tibia. In Iguana, the origin occupied the proximal two thirds on the dorsal surface and the distal two thirds on the ventral aspect of the shaft of the tibia. In Varanus, in contrast, the origin on the dorsal surface continues toward distal end of the tibia. The insertion was on the medial margin of MT I, as described by Russell and Bauer (2008). It was innervated by the fibular nerve.

Testudines: In the examined Chelydra, m. tibialis anterior arose from the dorsomedial margin of the tibia and inserted on the proximomedial end of MT I, as described by Walker (1973). The origin and insertion on bones were marked by a rugose, longitudinal sulcus, and a tubercle, respectively. It is innervated by the fibular nerve (Walker, 1973).

Crocodilia: In Paleosuchus and Crocodylus dissected in the present study, m. tibialis anterior arose from the proximal‐most portion of the dorsal aspect of the tibia marked with surface rugosity and inserted on the bulge on the dorsal aspect of each of MTs I and II. Laterally, the area of origin became broader proximodistally and was marked by distinct rugosity on the bone, as described by Suzuki et al. (2011). This muscle is innervated by the fibular nerve (Gadow, 1882; Cong et al., 1998; Suzuki et al., 2011).

Aves: In the examined Gallus and Grus, m. extensor digitorum longus took the origin from the broad surface between the cranial and lateral cnemial crests and the dorsolateral aspect of the tibial shaft. The area of origin tapered distally. It inserted on processes on the proximodorsal lips of all phalanges of digits II‐IV except for the most proximal phalanges (also described by Fujioka, 1962; Vanden Berge, 1975). This muscle is innervated by the common fibular nerve (Vanden Berge, 1975).

Comparison: The origin and innervation pattern of this muscle are conserved among sauropsids. However, the insertion is different between avians (on the distal phalanges) and non‐avian sauropsids (generally on MT I with some additional areas). The homology between non‐avian sauropsids and avians proposed here has also been considered, but not adopted, by Hutchinson (2002). Although the name ‘m. tibialis anterior’ is used in the majority of studies on sauropsids, the avian ‘m. extensor digitorum longus’ is adopted here as the general name to cleary indicate that this muscle is different from otherwise similarly named m. tibialis cranialis discussed above.

3.1.3. Musculus peroneus longus

Lepidosauria: M. peroneus longus (Russell and Bauer, 2008)

Testudines: M. peroneus anterior (Walker, 1973)

Crocodilia: M. peroneus longus (Suzuki et al., 2011)

Aves: M. fibularis longus (Vanden Berge and Zweers, 1993)

Lepidosauria: M. peroneus longus takes its origin from the lateral femoral epicondyle, just distal to the origin of m. flexor digitorum longus (Russell and Bauer, 2008). In the examined Iguana and Varanus, the insertion was marked by a depression on the dorsolateral aspect of the shaft of MT V (contra “lateral plantar tubercle” in Russell and Bauer, 2008). It is innervated by the fibular nerve (Jullien, 1967).

Testudines: In the examined Chelydra, m. peroneus anterior arose from the distal half of the dorsal aspect of the fibula and inserted on the dorsal aspect of the proximolateral margins of MT V and IV‐1. The site of origin on the lateral fibula was marked by a slightly excavated surface. It is innervated by the fibular nerve (Walker, 1973).

Crocodilia: In the dissected specimens of Paleosuchus and Crocodylus, m. peroneus longus arose from an almost entire laterodorsal aspect of the fibula (also described by Suzuki et al., 2011). This area of origin was the surface between longitudinal ridges on the dorsal and the lateral aspects of the bone. This muscle partly merged with m. peroneus brevis and inserted on the flat surface on the proximolateral margin of MT V, distally adjacent to a separate insertion site of m. peroneus brevis. This muscle is innervated by the superficial fibular nerve (Cong et al., 1998; Suzuki et al., 2011).

Aves: In Gallus, this muscle arises from the proximal margins of the cranial and lateral cnemial crests, the patellar tendon, and associated fascia (Fujioka, 1962). In Eudromia, the origin extends on the lateral aspect of the anterior cnemial crest (Suzuki et al., 2014). It inserts on soft tissues, sustentaculum tarsi, and the insertion tendon of the flexor perforatus digiti III (Fujioka, 1962; Vanden Berge, 1975). This muscle is innervated by the fibular nerve (Vanden Berge, 1975).

Comparison: The homology of this muscle hypothesized in the present study follows the one proposed by Dilkes (2000) and Hutchinson (2002). The areas of origin in crocodilians and testudines are similar to each other, but differ from those in both lepidosaurs and avians. The insertion is conserved among non‐avians, whereas the one in avians is different possibly because of the loss of MT V.

3.1.4. Musculus peroneus brevis

Lepidosauria: M. peroneus brevis (Russell and Bauer, 2008)

Testudines: M. peroneus posterior (Walker, 1973)

Crocodilia: M. peroneus brevis (Suzuki et al., 2011)

Aves: M. fibularis brevis (Vanden Berge and Zweers, 1993)

Lepidosauria: M. peroneus brevis takes its origin on the almost entire anterior, lateral and medial surfaces of the fibula for almost its entire length, and inserts on the process on the proximolateral margin of MT V (outer process; Russell and Bauer, 2008). This muscle is innervated by the fibular nerve, as is m. peroneus longus (Jullien, 1967).

Testudines: M. peroneus brevis arises from the distal end of the fibula and inserts on the proximal margin of the dorsal aspect of MT V, thus, acting with m. peroneus longus to extend and abduct digit V and probably also assisting in dorsiflexion of the pes (Walker, 1973). This muscle is innervated by the fibular nerve (Ribbing, 1938).

Crocodilia: In the dissected Paleosuchus and Crocodylus, m. peroneus brevis arose from the laterodorsal aspect of the distal two thirds of the shaft of the fibula and inserted on the proximolateral margin of MT V, as described by Cong et al. (1998) and Suzuki et al. (2011). The origin was a flat surface. It is innervated by the superficial fibular nerve (Cong et al., 1998; Suzuki et al., 2011).

Aves: M. fibularis brevis mainly arises from the most of the interosseal space between the tibia and the fibula (Fujioka, 1962; Vanden Berge, 1975; Yasuda, 2002) and inserts on a proximal surface near the lateral margin of the hypotarsus (tuberculum m. fibularis brevis; Vanden Berge and Zweers, 1993). The tibial origin was a narrow surface between two longitudinal ridges on the distal two thirds of the shaft, whereas the fibular origin was the dorsal surface of the distal half of the shaft. This muscle is innervated by the deep fibular nerve (Vanden Berge, 1975).

Comparison: Although the innervation pattern is different between crocodilians and avians, the homology of these muscles proposed here was also discussed and supported by Hutchinson (2002). The innervation pattern is conserved among sauropsids, except between crocodilians and avians, in which the superficial and deep branches of the fibular nerve supply the muscle, respectively.

3.1.5. Musculus adductor hallucis dorsalis

Lepidosauria: M. adductor et extensor hallucis et indicus (Russell and Bauer, 2008)

Testudines: M. extensor hallucis proprius (Walker, 1973)

Crocodilia: M. adductor hallucis dorsalis (Suzuki et al., 2011)

Lepidosauria: In the examined Iguana, m. adductor et extensor hallucis et indicus arose from a broad and flat or slightly depressed surface on the dorsolateral aspect of the distal fibula as well as from the medial half of a slight convex lip at the proximolateral margin of the tarsal facet of the astragalocalcaneum. This muscle inserted on the medial margin and the laterodistal part of the shaft of MT I as well as on a small area on the proximodorsal aspect of the shaft of MT II, as described by Russell and Bauer (2008). The insertion area is more limited in some taxa such as Varanus and Gekko (only on MT I) and Chamaeleo (only on MT II; Russell and Bauer, 2008). Varanus showed rugosity at the insertion area on the bone. The deep fibular nerve innervates this muscle (Ribbing, 1938:fig. 562).

Testudines: In the dissected specimen of Chelydra, m. extensor hallucis proprius arose from the distal end of the fibula and the dorsal aspect of the astragalocalcaneum, and the origin on the fibula was marked as a clear depression on the distodorsal margin of the bone. It distally merged with m. abductor hallucis and inserted on the lateral sides of the distal one third of MT I and the proximal half of I‐1 as well as on the medial side of the mid‐shaft of I‐1. In Trachemys, the origin on the astragalocalcaneum is absent (Walker, 1973, fig. 22). This muscle is innervated by the deep fibular nerve (Ribbing, 1938, fig. 560).

Crocodilia: In the examined Paleosuchus and Crocodylus, m. adductor hallucis dorsalis arose from the dorsal aspect of the distal fibula and inserted on the dorsal aspect of the proximal one third of the shaft of MT I, just proximal to the insertion of ‘m. tibialis anterior.’ In Crocodylus, the insertion has previously been described as divided into two sites (Suzuki et al., 2011). The presence of such two separate insertions, however, was not confirmed in the same species dissected in this study, thus, suggesting a possible intraspecific variation. The distal border of the insertion of this muscle was marked by a transverse ridge on the dorsal aspect of MT I. This muscle is innervated by the fibular nerve (Gadow, 1882; Ribbing, 1938; Cong et al., 1998; Suzuki et al., 2011).

Aves: This muscle is apparently absent in avians.

Comparison: The sites of origin and insertion and the innervation pattern are almost completely conserved among non‐avian sauropsid taxa. The homology of this muscle among sauropsids has already been discussed by Gadow (1882). Although Hutchinson (2002) regard this muscle as a homologue of m. extensor hallucis longus in avians (sensu Vanden Berge and Zweers, 1993), such a homology hypothesis is not accepted in this study (see the description of m. extensor hallucis brevis below).

3.1.6. Musculus extensor digitorum brevis

Lepidosauria: Mm. extensores digitores breves, in part (Russell and Bauer, 2008)

Testudines: Mm. extensores digitorum breves (Walker, 1973)

Crocodilia: M. extensor digitorum I, II et III (Suzuki et al., 2011)

Lepidosauria: In Iguana dissected in the present study, two proximal heads of mm. extensores digitores breves arose from the dorsal depression on the astragalus and inserted on the proximodorsal lip of each phalanx of digits III and IV. These slips have been described as two portions of mm. extensores breves (Russell and Bauer, 2008). In Varanus dissected in the present study, additional two slips inserting on the proximodorsal lips of digits I and II were present. This muscle is innervated by the deep fibular nerve (Ribbing, 1938).

Testudines: In the examined Chelydra, mm. extensores digitorum breves arose from the depression on the dorsal aspect of distal tarsal (DT) IV, and distally merged with mm. interossei dorsales, which together inserted on the proximodorsal lips of distal phalanges of digits III and IV. In Trachemys, this muscle has an additional origin from DT III and insertion on digit II (Walker, 1973). This muscle is innervated by the fibular nerve (Ribbing, 1938).

Crocodilia: In the dissected specimens of Paleosuchus and Crocodylus, m. extensor digitorum I, II et III arose from the depression on the dorsal aspect of the astragalus and inserted dorsally on digits I–III by the dorsal aponeurosis. In Caiman, however, the origin is not on the astragalus but on the soft tissue between this bone and the calcaneum (Suzuki et al., 2011). This muscle is innervated by the deep fibular nerve (Gadow, 1882; Cong et al., 1998; Suzuki et al., 2011).

Aves: This muscle is apparently absent in avians.

Comparison: The concentrated origin on the dorsal aspect of the tarsus is conserved among non‐avian sauropsid taxa. Between lepidosaurs and crocodilians, although the bellies inserting on digits I and II are sometimes absent in the former (at least in Iguana) and the one on digit IV is absent in the latter, the similarity in the concentrated origin on the astragalus and its osteological correlation suggests the homologous relationship between the muscles described here. Although the origin in turtles is slightly different from these lepidosaurian and crocodilian muscles, homology of this muscle among these taxa was also supported by Gadow (1882). Although this muscle has been distinguished from other short extensors in crocodilians as m. extensor digitorum I, II et III by Suzuki et al. (2011), the name m. extensor digitorum brevis is proposed as the standard name for this and all homologous muscles because these muscles sometimes lack insertions on digits I–II and/or gains the one on digit IV in non‐crocodilian sauropsids.

3.1.7. Musculus extensor hallucis brevis

Lepidosauria: Mm. extensores digitores breves, in part (Russell and Bauer, 2008)

Testudines: M. abductor hallucis (Walker, 1973)

Crocodilia: M. extensor hallucis brevis (Suzuki et al., 2011)

Aves: M. extensor hallucis longus (Vanden Berge and Zweers, 1993)

Lepidosauria,Testudines,and Crocodilia: The morphology of this muscle was mostly conserved among non‐avian sauropsids. In the examined leidosaurs and crocodilians, it took the main origin from the dorsal aspect of MT I and inserted on the proximodorsal lips of I‐1 and I‐2, as described by Cong et al. (1998) and Suzuki et al. (2011). It is innervated by the deep fibular nerve (Ribbing, 1938; Russell and Bauer, 2008; Suzuki et al., 2011). In testudines, m. abductor hallucis has an additional origin on DT I (in Trachemys; Walker, 1973). In the examined Chelydra, it instead has the additional origin on I‐1. The innervation is by the deep fibular nerve as in lepidosaurs and crocodilians (Ribbing, 1938, fig. 560).

Aves: In the dissected specimens of Gallus and Grus, m. extensor hallucis longus originated from the medial portion of the sulcus extensorius and inserted on the proximodorsal lips of I‐1 and I‐2, as described by Fujioka (1962). An additional fleshy origin on the dorsal aspect of MT I was also observed. Both origins were marked by longitudinal depressions on the medial parts of the dorsal aspects of the tarsometatarsus and MT I. This muscle is innervated by the deep fibular nerve (Vanden Berge, 1975).

Comparison: Although the area of origin of the avian m. extensor hallucis longus is different from that of m. extensor hallucis brevis in non‐avian sauropsids, these muscles are the most similar in the site of insertion and innervation patterns, suggesting their homologous relationships.

3.1.8. Musculus extensor digiti II

Lepidosauria: Mm. extensores digitores breves, in part (Russell and Bauer, 2008)

Testudines: Mm. interossei dorsales, in part (Walker, 1973)

Crocodilia: M. extensor digiti II (Suzuki et al., 2011)

Lepidosauria: In the dissected Iguana and Varanus, the slip of m. extensores digitores breves for digit II arose from the dorsal aspect of MT II and inserted on the proximodorsal lip of each phalanx of digit II, as described by Russell and Bauer (2008). This muscle is innervated by the deep fibular nerve (Ribbing, 1938)

Testudines: In the examined Chelydra, a portion of mm. interossei dorsales arose from the dorsal aspects of astragalocalcaneum, DT I, MT II, and II‐1, and inserted on the proximodorsal lips of distal phalanges of digit II. This muscle is the most likely to correspond to a portion of mm. interossei dorsales described by Walker (1973), although the origin of the latter does not attach on II‐1. It is innervated by the deep fibular nerve (Ribbing, 1938).

Crocodilia: In the dissected Paleosuchus and Crocodylus, m. extensor digiti II arose from the dorsal aspect of MT II and inserted on the proximodorsal lip of each phalanx of digit II, as described by Suzuki et al. (2011). This muscle is innervated by the deep fibular nerve (Ribbing, 1938; Cong et al., 1998; Suzuki et al., 2011).

Aves: This muscle is apparently absent in avians.

Comparison: The origin from the dorsal aspect of MT II and the innervation pattern are both conserved among non‐avian sauropsids. The additional origin on II‐1 is characteristic of Testudines but can be regarded as an expansion of the MT II origin. Although an additional origin on the proximal end of MT III was described by Russell and Bauer (2008) for the slip of mm. extensores digitores breves inserting on digit II in lepidosaurs, this head is recognized as a homologue of m. interosseous dorsalis digiti II in the present study.

3.1.9. Musculus extensor digiti III

Lepidosauria: Mm. extensores digitores breves, in part (Russell and Bauer, 2008)

Testudines: Mm. interossei dorsales, in part (Walker, 1973)

Crocodilia: M. extensor digiti III (Suzuki et al., 2011)

Aves: M. extensor brevis digiti III (Vanden Berge and Zweers, 1993)

Lepidosauria: In the dissected specimens of Iguana and Varanus, a slip of mm. extensores digitores breves arose from the dorsolateral surface of the MT III shaft, as described by Russell and Bauer (2008). This muscle distally merged with the portions of m. extensor digitorum brevis and m. interosseous dorsalis digiti III (see below), and inserted on the proximodorsal lip of each phalanx of digit III. This muscle is supplied by the deep fibular nerve (Ribbing, 1938). Although Russell and Bauer (2008) described additional origins from the lateral aspect of the distal portion of MT II and the dorsal aspect of the distal one half of MT IV, such origins were not confirmed in the present study.

Testudines: In the examined Chelydra, a portion of mm. interossei dorsales mainly arose from the dorsal aspect of MT III with additional origins on DT III and III‐1. It inserted on the distal phalanges of digit III by a dorsal aponeurosis. In Trachemys, the origin on III‐1 and the insertion on III‐2 are absent (Walker, 1973). This muscle is supplied by the deep fibular nerve (Ribbing, 1938).

Crocodilia: In the dissected Paleosuchus and Crocodylus, m. extensor digiti III arose from the dorsal surface of MT III and inserted on the proximodorsal lip of each phalanx of digit III by a dorsal aponeurosis. There are some additional origins on the proximolateral margin of MT II in Caiman (Suzuki et al., 2011) and dorsal aspect of DT III in Alligator (Cong et al., 1998). Although Cong et al. (1998) reported an additional origin arising from the astragalus that is shared with M. extensor digiti II, this slip is here regarded as a part of m. extensor digiti I, II et III following Suzuki et al. (2011). This muscle is innervated by the fibular nerve (Gadow, 1882; Ribbing, 1938; Cong et al., 1998; Suzuki et al., 2011).

Aves: The possible homologue of the crocodilian m. extensor digiti III in Gallus and Grus arose from the dorsal aspect of the distal half of the tarsometatarsus and inserted on the proximodorsal lip of III‐1. In the examined Gallus, the origin was marked by a slightly depressed rugose surface. This muscle is innervated by the superficial fibular nerve (Vanden Berge, 1975).

Comparison: The origin and insertions of these muscles are mostly conserved among sauropsids except for the presence of an additional origin in Testudines and concentration of the insertion in Aves. These muscles are consistently supplied by the deep fibular nerve in lepidosaurs, testudines, and crocodilians and appear to be homologous among these clades (Ribbing, 1938).

3.1.10. Musculus extensor digiti IV

Lepidosauria: Mm. extensores digitores breves, in part (Russell and Bauer, 2008)

Testudines: Mm. interossei dorsales, in part (Walker, 1973)

Crocodilia: M. extensor digiti IV (Suzuki et al., 2011)

Lepidosauria: In the examined Iguana, a portion of mm. extensores digitores breves, i.e., a slip arising from the lateral half of a slight convex lip at the proximolateral margin of the tarsal facet of the astragalocalcaneum, was joined on its deeper surface by some fibers of a slip arising from the dorsolateral (or “mesial” in Russell and Bauer, 2008) aspect of MT IV. A single tendon inserted on the proximodorsal lip of the ungual of digit IV, with accessory insertions on the proximal ends of IV‐2, IV‐3, and IV‐4. This muscle is innervated by the superficial fibular nerve (Ribbing, 1938).

Testudines: In the dissected Chelydra, a portion of mm. interossei dorsales had the main origin from the dorsal aspect of MT IV and additional origins from DT IV and IV‐1 and inserted on the distal phalanges of digit IV by a dorsal aponeurosis. In Trachemys, origin from IV‐1 and insertion on IV‐2 are absent (Walker, 1973). This muscle is innervated by the fibular nerve (Ribbing, 1938; Walker, 1973).

Crocodilia: In the dissected specimens of Paleosuchus and Crocodylus, m. extensor digiti IV arose from the dorsal surface of MT IV and inserted on the proximodorsal lip of each phalanx of the digit IV by a dorsal aponeurosis. Additional origins on the dorsal aspect of DT IV and the connective tissue between the calcaneum and DT IV have been described in Alligator (Cong et al., 1998) and Caiman (Suzuki et al., 2011), respectively. This muscle is innervated by the superficial fibular nerve in Caiman (Suzuki et al., 2011) and by the deep fibular nerve in Alligator (Cong et al., 1998).

Aves: This muscle is apparently absent in avians.

Comparison: All of these muscles in Lepidosauria, Testudines, and Crocodilia commonly arise from the dorsal aspect of MT IV, insert dorsally on the phalanges of digit IV, and are innervated by the fibular nerve. In addition, each of these muscles has one or more additional origins such as proximal heads from the tarsus or soft tissues.

3.1.11. Musculus interosseous dorsalis digiti II

Lepidosauria: Mm. extensores digitores breves, in part (Russell and Bauer, 2008)

Testudines: Mm. interossei dorsales, in part (Walker, 1973)

Crocodilia: M. interosseous dorsalis digiti II (Suzuki et al., 2011)

Aves: M. abductor digiti II (Vanden Berge and Zweers, 1993)

Lepidosauria: In the examined Iguana and Varanus, a part of mm. extensores digitores breves arose from the ridge‐like, longitudinal rugose area along the lateral margin of MT I by a stout tendon, and inserted on the proximodorsal lip of each phalanx of digit II by a dorsal aponeurosis. In Iguana, the origin tendon extended along this muscle and joined the medial portion of the aponeurosis, which is regarded as an “oblique intermetatarsal ligament” by Russell and Bauer (2008). In Varanus, this tendon inserted on the medial margin of the distal portion of MT II, just proximal to the distal condyle. This muscle is innervated by the deep fibular nerve (Ribbing, 1938).

Testudines: In the dissected specimen of Chelydra, there was a slip arising from the rugosity on the proximomedial margin of the dorsal aspect of MT I. This slip merged with the main slip of mm. interossei dorsales extending to digit II and inserted on the distal phalanges of digit II by a dorsal aponeurosis. This muscle is innervated by the fibular nerve (Walker, 1973).

Crocodilia: In the dissected Paleosuchus and Crocodylus, m. interosseous dorsalis digiti II arose from the depression on the lateroplantar aspect of MT I, accompanied by a stout tendinous structure. The insertion tendon of this muscle joined the dorsal aponeurosis of digit II, but most of its fibers inserted on the proximodorsal lip of II‐1, as described by Suzuki et al. (2011). This muscle is innervated by the deep fibular nerve (Gadow, 1882; Suzuki et al., 2011).

Aves: In the examined specimens of Gallus and Grus, m. abductor digiti II arose from both the lateral aspect of MT I and the dorsomedial aspect of the tarsometatarsus and inserted on the medioplantar tubercle at the proximal end of II‐1. The origin on the tarsometatarsus was marked by an oblique groove on the medial aspect of the shaft and the fossa metatarsi I. This muscle is innervated by the deep fibular nerve (Vanden Berge, 1975).

Comparison: The muscles described above all share their origin on MT I, insert on digit II, and are innervated by the deep fibular nerve. These conserved patterns suggest these are homologous with one another. The association of this muscle with the ligament‐like structure in both Lepidosauria and Crocodilia also supports this hypothesis.

3.1.12. Musculus interosseous dorsalis digiti III

Lepidosauria: Mm. extensores digitores breves, in part (Russell and Bauer, 2008)

Testudines: Mm. interossei dorsales, in part (Walker, 1973)

Crocodilia: M. interosseous dorsalis digiti III (Suzuki et al., 2011)

Lepidosauria: In the dissected Iguana and Varanus, a slip of mm. extensores digitores breves arose tendinously from the ridge‐like, longitudinal rugose area along the lateral margin of the proximal half of MT II. Distally, this muscle forms the medial portion of the dorsal aponeurosis of digit III, which inserted on the proximodorsal lip of each phalanx. In Varanus, an additional tendinous insertion was present on the medial margin of the distal portion of MT III, just proximal to the distal condyle. The belly of mm. extensores digitores breves for digit III described as “arising from the lateral aspect of the distal portion of the shaft of MT II” by Russell and Bauer (2008) probably corresponds to this muscle and represents a possible intraspecific variation. This muscle is innervated by the deep fibular nerve (Ribbing, 1938).

Testudines: In the examined specimen of Chelydra, one of several heads of mm. interossei dorsales arose from the rugosity on the proximomedial margin of the dorsal aspect of MT II and inserted on the proximodorsal lips of distal phalanges of digit III by a dorsal aponeurosis. This muscle is innervated by the fibular nerve (Walker, 1973).

Crocodilia: In the dissected Paleosuchus and Crocodylus, m. interosseous dorsalis digiti III arose from the rugose surface on the dorsal and lateral aspects of the lateral margin of proximal MT II. The insertion tendon of this muscle joined the dorsal aponeurosis of digit III, but most of its fibers inserted on the proximodorsal lip of III‐1, as described by Suzuki et al. (2011). This muscle is innervated by the fibular nerve (Gadow, 1882; Suzuki et al., 2011).

Aves: This muscle is apparently absent in avians.

Comparison: Although m. extensor digiti brevis III in avians has an insertion similar to those of the non‐avian muscles listed here, the former avian muscle is not regarded as the homologue of m. interosseous dorsalis digiti III in the present study. This is mainly because of the origin site of this avian muscle on the middle of the distal half of the tarsometatarsus more likely corresponds to MT III, rather than MT II from which m. interosseous dorsalis digiti III in non‐avians arises. In addition, this muscle in avian does not act as an adductor of digit III unlike m. interosseous digiti III in crocodilians (Suzuki et al., 2011) but instead is an extensor of this digit (Vanden Berge, 1975).

3.1.13. Musculus interosseous dorsalis digiti IV

Lepidosauria: Mm. extensores digitores breves, in part (Russell and Bauer, 2008)

Testudines: Mm. interossei dorsales, in part (Walker, 1973)