Abstract

The purpose of this investigation was to determine the effects of vocal training on neuromuscular junction (NMJ) morphology and muscle fiber size and composition in the thyroarytenoid muscle, the primary muscle in the vocal fold, in younger (9-month) and older (24-month) Fischer 344 × Brown Norway male rats. Over 4 or 8 weeks of vocal training, rats of both ages progressively increased their daily number of ultrasonic vocalizations (USVs) through operant conditioning and were then compared to an untrained control group. Neuromuscular junction morphology and myofiber size and composition were measured from the thyroarytenoid muscle. Acoustic analysis of USVs before and after training quantified the functional effect of training. Both 4- and 8-week training resulted in less NMJ motor endplate dispersion in the lateral portion of the thyroarytenoid muscle in rats of both ages. Vocal training and age had no significant effects on laryngeal myofiber size or type. Vocal training resulted in a greater number of USVs with longer duration and increased intensity. This study demonstrated that vocal training induces laryngeal NMJ morphology and acoustic changes. The lack of significant effects of vocal training on muscle fiber type and size suggests vocal training significantly improves neuromuscular efficiency but does not significantly influence muscle strength changes.

Keywords: Acoustics, Laryngeal muscle, Neuromuscular junction, Presbyphonia, Vocal fold atrophy

Age-related voice impairments occur in up to a third of adults aged older than 65 years, negatively affecting communicative ability and quality of life (1–3). One cause of voice disorders in senescence is laryngeal muscle denervation, loss of muscle mass (sarcopenia), and muscle weakness (dynapenia) (4–6). These natural aging processes can lead to muscle atrophy of the thyroarytenoid muscle (the primary muscle of the vocal fold), resulting in functional impairments in vocal fold vibration, aberrant vocal quality, difficulty with vocal projection, and increased vocal fatigue (7–9). As the number of people aged 65 years or older continues to increase, preventative and rehabilitative behavioral interventions for age-related voice problems will become essential for improving health, safety, and well-being in the aging population. Although there is emerging clinical support for the use of vocal exercise training programs to improve vocal function in older adults (10–12), there is little understanding of the specific neuromuscular mechanisms that these interventions are targeting (eg, neuromuscular coordination, muscle endurance, or muscle strength). Identifying optimal vocal exercise dose is also necessary to determine the frequency and intensity of voice training needed to make improvements in the aging voice.

Direct study of the effects of vocal training on laryngeal neuromuscular mechanisms in humans is challenging. The laryngeal muscles are encapsulated within the cartilaginous framework of the larynx and the small size of the vocal fold muscles precludes muscle biopsy. Therefore, our lab has pioneered the use of a behavioral vocal training paradigm in aging rodents that naturally produce ultrasonic vocalizations (USVs) to communicate with other rats (13,14). Previous work has demonstrated the rat larynx has similar neuromuscular structure and function to humans and that USVs and human vocalizations are produced using similar laryngeal muscle function (15). These parallels between human and animal models provide an optimal opportunity to study changes in neuromuscular structure and function in the larynx in response to increased physiological laryngeal muscle use and aging.

Our previous work with this model demonstrated age has a negative effect on post-synaptic neuromuscular junction (NMJ) motor endplate morphology within larynges of old rats with greater motor endplate dispersions and larger endplate areas, likely due to the nerve denervation and re-innervation that naturally occurs with aging (13). Old rats who were trained to increase their vocalizations over 8 weeks had smaller motor endplate dispersions in the lateral thyroarytenoid muscle resulting in NMJ morphology more comparable to young-adult rats compared to the old untrained control rats (13). These findings suggest vocal training can reduce age-related neuromuscular changes in the larynx. In a subsequent study examining vocal training duration in young rats, we again found significant decreases in NMJ motor endplate dispersion in the larynx with 8 weeks of training but not 4 weeks, suggesting a longer duration of vocal training than what is typically recommended in the limb literature may be needed to induce structural changes within the larynx (14).

Interactions between the duration of vocal training and age on NMJs within the thyroarytenoid muscle have not been directly investigated. Studying how vocal exercise may affect myosin heavy chain (MHC) composition within the muscle fiber and fiber size changes (hypo/hypertrophy) can provide insights into whether vocal exercise involves endurance or strength adaptations in the thyroarytenoid muscle. Additionally, studying changes in USV acoustics can provide insight into the functional effects of training. Therefore, we investigated the effects of age and vocal training duration and their interactions on (a) NMJ morphology, (b) muscle fiber type composition and size, and (c) USV acoustics.

Based on our previous work and current knowledge from the exercise physiology limb literature, we formed several hypotheses. First, we hypothesized that NMJ morphology within the larynx would only be significantly affected by 8 weeks of training, not by 4 weeks, with a dampened training effect in the older trained rats compared to younger trained animals. This hypothesis was based on our previous work demonstrating significant changes with 8 weeks of vocal training and the established literature on the effects of sarcopenia on neuromuscular structure and function in the limbs (13,14,16,17). Second, we anticipated reduced NMJ motor endplate dispersion ratios in larynges of vocally trained animals, suggestive of vocal training as a type of low-intensity endurance exercise. This hypothesis was informed by our previous work demonstrating similar morphological patterns in the NMJ of laryngeal muscle (13,14) and previous limb literature showing decreased endplate dispersions with low-intensity endurance exercise (18). Third, we hypothesized that the number and intensity of USVs would increase relative to the duration of vocal training, with greater pre-to-post training changes in the older group compared to the younger group. This hypothesis was based on previous USV investigations in old rats (13,19,20).

Methods

Animals

A total of 52 Fischer 344 × Brown Norway (F344BN) male rats were obtained from the National Institute on Aging animal colony, equally divided across 2 age groups. The younger male rats were 9 months old and the older male rats were 24 months old at the conclusion of the experiment. Only male rats were selected for the experimental and control groups because of the unknown effects of hormonal fluctuations—previously observed in female rats—on the vocal muscle structure and function (21). Four young-adult female rats (approximately 12 months old) were used to elicit vocalizations from the male rats and were cycled through the male rats based on the males’ responses to the females. Young and older male rats were randomly and evenly divided into 3 training groups involving different doses of weekly progressive vocal exercise training (8 weeks, 4 weeks, and untrained controls), for 8 rats per age × training group combination (48 total). Four of the older male rats in the 2 vocal training groups were non-responders to behavioral training—defined as rats that did not produce USVs in response to the female rats across multiple days and exposures—and were therefore replaced with 4 additional male rats of the same age. Based on a power analysis from our previous work (13), a minimum of 6 animals per group was needed to provide 95% power to detect significant changes in motor endplate dispersions at α = .05. Sample size was increased to n = 8 per group to account for attrition (eg, illness, unplanned death). The Institutional Animal Care Use Committee (IACUC) at New York University School of Medicine approved the animal use protocol. All rats were kept on a 12/12 reversed light cycle. Each male rat was single-housed because previous work has demonstrated rats that are isolated are more responsive to vocal training (22); the 4 female rats were kept in pairs in between training sessions. No animals were ill during the experiment and all survived to the end of the behavioral training time point.

Behavioral Training

Before initiation of the vocal training, all male and female rats underwent a 2-week habituation period upon arrival to acclimate to their new environment as well as to familiarize them to the opposite-sex exposure paradigm used to elicit initial vocalizations. After the 2 weeks, male rats in both the 4- and 8-week vocal training groups underwent training to progressively increase their vocalizations 6 days a week for either 4 or 8 weeks, depending on which vocal training group they had been assigned. The behavioral model involves a previously established operant conditioning paradigm (13,23). Briefly, a sexually receptive female rat is introduced to the home cage of a male rat, and then removed once the male expresses an interest. The removal elicits USVs from the male, which are then rewarded with a sucrose treat. Subsequent USVs can be shaped using sucrose rewards to elicit increased number of vocalizations while simultaneously phasing out the presentation of the female rat. Older and younger male rats in the control group were exposed to female rats but did not receive a sucrose reward when vocalizing in response to her removal from the home cage. The control group was instead position trained in their home cage to receive a sucrose reward at one specific location within the home cage. Male and female pairs were randomly selected based on whether the female rat was in estrous and thus sexually receptive to the male rat.

During the first week, the female was first introduced and then reintroduced to the male if vocalizations stopped for longer than a minute, for a maximum of 3 introductions and a total of 10 minutes of USV or position training. The female rat was placed in the male’s cage and then put into an isolation chamber so the male could not hear her calls. For the first week, each rat in the 2 USV training groups had a target of at least 30 USVs per training session. Individual daily training targets for each subsequent week were calculated by increasing the average number of USVs produced during the last 2 days of training at the end of each week by 50%. After 4 weeks, rats in the 8-week group were trained to increase their vocalizations by 20% each week to prevent a ceiling effect with training.

At the end of training, rats were euthanized via CO2 inhalation and confirmed with thoracotomy. The weight of each animal was documented to account for weight as a covariate of muscle fiber size. The larynx of each rat was excised and bisected dorsally and ventrally between the arytenoids, vocal folds, and midline of the thyroid cartilage. The right side of the larynx was used for NMJ morphology analysis while the left side of the larynx was used for muscle fiber analysis. Plantaris hindlimb muscle from each animal was also acquired for positive control comparisons of muscle fiber analysis. This particular hindlimb muscle was chosen because it is composed primarily of the same type of MHC Type IIb/IIx muscle fiber hybrid previously found in the larynx (24).

Neuromuscular Junction Preparation, Imaging, and Analysis

The right hemilarynx of each animal was fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 1 hour, rinsed 3 times for 15 minutes each in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and cryoprotected overnight in 20% sucrose solution. The next day, the hemilarynx was imbedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (NEG-50, Thermo Scientific) and flash-frozen in isopentane chilled to just above its freezing point by liquid nitrogen. Laryngeal tissue was sectioned longitudinally at 35 µm with a Leica CM3050 cryostat along the length of the thyroarytenoid muscle belly. Sections were placed on positively charged slides (SuperFrost Plus, Thermo Scientific) and rinsed with PBS twice for 5 minutes before being permeabilized in 0.3% TritonX-100 in Tris-buffered saline for another 5 minutes. The tissue was then blocked in wash buffer (5.0% normal goat serum, 1.0% bovine serum albumin, and 0.01% Triton X-100 in Tris-buffered saline) for 90 minutes at room temperature. The tissue was incubated overnight at 4°C in α-bungarotoxin directly conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 fluorochrome (1:1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) to label post-synaptic acetylcholine receptors; the same tissue samples were simultaneously incubated in anti-synaptotagmin-2 primary antibody (1:400; Zebrafish International Resources Center, University of Oregon) to label pre-synaptic nerve terminal membranes. The following day, the tissue was rinsed in wash buffer 3 times for 5 minutes each and then incubated in Alexa 546 secondary antibody (1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 4 hours at room temperature to tag the anti-synaptotagmin-2 primary antibody. Finally, the tissue was rinsed 3 times for 5 minutes each before being cover slipped with Prolong Gold antifade reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Ten randomly selected NMJs within the lateral and medial thyroarytenoid muscle belly (LTA and MTA, respectively) were imaged for each animal across several laryngeal sections on different slides to account for possible intramuscular variability using a Zeiss 700 spectral confocal microscope. The LTA and MTA were imaged separately due to known differences between their morphology, innervation, and function (13,25). Each NMJ was collected in a 3-dimensional (3D) 0.5-µm thick z-stack. The image stacks were analyzed using an automated custom ImageJ macro, which involved rotation of the z-stack until the maximum area of the NMJ was projected forward and flat (en face) on the computer screen. The following parameters were calculated: (a) motor endplate dispersion ratio (%), (b) total motor endplate area (µm2), and (c) pre-postsynaptic overlap between the endplate and nerve terminal (%).

These NMJ parameters represent neuromuscular remodeling previously shown with increased physiological activity in skeletal muscle (13,26–28) (refer to Johnson et al. (13,28) for comprehensive description of how these parameters were acquired and calculated). The type of morphological patterns within the NMJ is dependent on age and adaptations to task specificity. For example, NMJ motor endplates in skeletal muscle have been shown to become more dispersed with aging (13,29). Whereas increased endplate dispersions have also been shown to occur with adaptations to high-intensity strength training, motor endplates become less dispersed with low-intensity endurance training (18,29).

Motor endplate dispersion ratios and pre–post synaptic overlap parameters met assumptions of variance with Bartlett test of homogeneity of variances. Main effects of age and training group and their interactions were statistically analyzed using 2-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) in R language for statistical computing and graphics (http://www.r-project.org/). The motor endplate area parameter did not meet variance assumptions and was subsequently analyzed using a Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric 1-way ANOVA by ranks. Post hoc pairwise comparison analysis was determined using t tests with pooled standard deviations for parametric tests and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for non-parametric tests.

Myofiber Preparation, Imaging, and Analysis

Left hemilarynges and hindlimbs of each animal for muscle fiber analysis were prepared and processed using the same method as the NMJ protocol, with the exception of formaldehyde fixation due to previous work showing that fixation reduces antigenicity of MHC antibodies in muscle tissue (30,31). Tissue was sectioned in the coronal plane at 10 µm to acquire muscle cross-sections. The tissue sections were air-dried on positively charged slides for 10 minutes, blocked in 10% normal goat serum in PBS for 90 minutes at room temperature, and then incubated overnight in primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer at 4°C. Antilaminin primary antibody was used to label muscle fiber outlines (1:100; Sigma-Aldrich); MHC Type IIb and all but MHC Type IIx muscle fibers were stained with BF-F3 and BF-35 primary MHC antibodies, respectively (1:100; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank).

Sections were rinsed the following day for 3 times for 5 minutes each in PBS and then incubated in conjugated secondary antibodies for 4 hours at room temperature. Alexa Fluor 405 goat/anti-rabbit IgG, AF594 goat/anti-mouse IgM, and AF488 goat/anti-mouse IgG1 secondary antibodies were used to label laminin, MHC IIb, and all but 2× fibers, respectively. Sections were once again rinsed in PBS 3 times for 5 minutes each and then coverslipped with ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Fibers MHC IIa and MHC IIL (sometimes also referred to as IIeo, found in oculomotor muscle) were also labeled on separate slides using SC-71 (1:100; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) for MHC IIa and 4a6 (1:4; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) for MHC IIL as primary MHC antibodies and Alexa Fluor 488 goat/anti-mouse IgG1 and Alexa Fluor 594 goat/anti-mouse IgM as corresponding secondary antibodies. Finally, plantaris sections were stained for laminin, MHC IIb, and MHC IIx fibers using the same methods as for the laryngeal muscle.

Each muscle section was imaged using a Zeiss Axio Observer at 20× magnification. Medial thyroarytenoid (vocalis division) and LTA (external division) muscles were cropped and saved separately in ImageJ for separate muscle fiber analysis. Muscle fiber composition and size were analyzed for each thyroarytenoid section (MTA and LTA, respectively) using the semiautomatic muscle analysis (SMASH) application (32). To examine muscle fiber size and, therefore, the effects of USV training on laryngeal muscle hypertrophy, minimum Feret diameter—the minimum distance found between 2 parallel lines rotated around the edges of a muscle fiber—was calculated for each muscle fiber (33,34). Minimum Feret diameter correlates with muscle cross-sectional area, but the advantage of this method over cross-sectional area is that it is resistant to variability caused by slight differences in orientation of muscle sectioning (33). The total number of fibers for each MTA, LTA, and plantaris muscle as well as number of stained MHC Type IIb and IIx fiber types were identified automatically using SMASH. Because there were so few MHC Type IIa and IIL fibers in the muscle, the number of fibers for these 2 muscle types were determined manually. Muscle composition was determined by calculating the percentage of each MHC muscle fiber type by the total number of fibers within the MTA, LTA, and plantaris, respectively.

Linear mixed effect models were conducted on fiber size, with animal weight and fiber type as covariates, for MTA, LTA, and plantaris using R language for statistical computing and graphics (http://www.r-project.org/). Of note, muscle fiber MHC Types IIa and IIL accounted for less than 0.1% of the total fibers in each muscle and were therefore excluded from statistical analysis.

Acoustic USV Recording and Analysis

Ultrasonic vocalizations were recorded using Avisoft RECORDER (Avisoft Bioacoustics, Glienicke, Germany, version 4.2) prior to starting vocal training (pre-training) and at the end of the training protocol (post-training). Ultrasonic vocalizations were analyzed using DeepSqueak 2.0 (35) in MATLAB (version 9.4.0.813654 [R2018a]; The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA) to measure the following 6 parameters: (a) number of vocalizations per session, (b) intensity (dB/kHz), (c) duration (ms), (d) frequency (kHz), (e) bandwidth (kHz range), and (f) sinuosity (a dimensionless quantity of the ratio between the Euclidean distance of a straight line and curvilinear length along a curve. This parameter captures complexity of frequency modulated USVs).

Individual average delta change scores between pre- and post-training time points were calculated for each of the 6 acoustic USV parameters. Mixed-model ANOVAs were run on each parameter to assess the main effects of age (younger/older) and training group (control/4 weeks/8 weeks) and their interaction. Post hoc comparisons of significant main or interaction effects were analyzed with Bonferroni-corrected pairwise t tests.

Results

Neuromuscular Junction Morphology

The 3 measures of NMJ morphology, motor endplate area, motor endplate dispersion, and synaptic overlap, are summarized by age and training group main effects in Table 1 and interactions in Supplementary Table 1. No statistically significant interaction effects between age and training were observed.

Table 1.

The Mean ± SD of Neuromuscular Junction (NMJ) Morphology Parameters Summarized by Age (n = 24 per group) and Training Conditions (n = 16 per group)

| NMJ Parameter |

Muscle | Younger | Older | Control | 4 wk | 8 wk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motor endplate area (µm2) | LTA | 263.2 ± 58.8 |

291.7 ± 67.2 |

263.3 ± 67.6 |

277.7 ± 68.2 |

291.3 ± 56.9 |

| MTA | 146.8 ± 37.5 |

185.1 ± 56.01a |

154.7 ± 54.4 |

173.4 ± 56.3 |

169.8 ± 42.7 |

|

| Motor endplate dispersion (%) | LTA | 22.0 ± 9.0 |

25.0 ± 12.0 |

31.9 ± 10.9 |

20.3 ± 6.5b |

18.3 ± 8.7b |

| MTA | 15.8 ± 8.7 |

18.5 ± 9.1 |

19.1 ± 8.7 |

17.0 ± 9.6 |

15.2 ± 8.6 |

|

| Overlap (%) | LTA | 71.2 ± 25.2 |

80.1 ± 20.8 |

74.6 ± 21.2 |

75.6 ± 22.2 |

76.8 ± 27.4 |

| MTA | 94.0 ± 8.6 |

95.0 ± 5.8 |

93.7 ± 9.9 |

93.6 ± 6.5 |

96.0 ± 4.6 |

Notes: LTA = lateral thyroarytenoid; MTA = medial thyroarytenoid. Although there were no significant differences between age groups in the laryngeal muscle, average motor endplate dispersion ratios were larger in the older control group compared to the younger control group, which is consistent with morphological patterns in NMJs with senescence. These descriptive differences align with previous literature by Johnson et al. (13) showing greater dispersion ratios in older control animals compared to younger animals.

aSignificant age difference (p ≤ .05) from young group.

bSignificant training difference (p ≤ .05) from control group.

Effects of age

Significant age-related differences were found in the MTA with greater motor endplate area in older animals compared to younger animals (F[1,42] = 8.10, p = .007); age-related differences with motor endplate area were not observed in the LTA (F[1,42] = 2.47, p = .12). Significant age-related differences were also not observed in motor endplate dispersion ratios in either the MTA (F[1,42] = 1.08, p = .3) or the LTA (F[1,42] = 1.41, p = .24), nor were there age-related differences in synaptic overlap in either the MTA (χ 2[2] = 0.003, p = .95) or the LTA (F[1,42] = 1.77, p = .19).

Effects of training

The primary effect of training was significantly reduced endplate dispersion within the LTA (F[2,42] = 10.86, p < .001) in both the 4-week (p = .001) and 8-week (p < .001) training groups relative to the control group (Figure 1). Although there were smaller dispersion ratios in the MTA in the younger 4-week trained and both younger and older trained in the 8-week group, compared to controls, training effects on motor endplate dispersion in the MTA was not significant (F[2,42] = 0.77, p = .47); there were also no significant training effects on motor endplate area or synaptic overlap (Figure 2) in the MTA or LTA.

Figure 1.

(A) Motor endplate dispersion ratio was smaller in both the 4- and 8-week training groups in both younger and older animals in the lateral thyroarytenoid (LTA) muscle, but not the medial thyroarytenoid (MTA) muscle. Representative images of motor endplates from animals in the (B) trained and (C) untrained control groups. Significant differences within each age group are indicated in Figure 1A as follows: * = experimental group significantly different from control group (age groups combined). Dark dots in the box and whisker plots represent the median and the box the interquartile range; the whiskers extend to the 95% confidence interval for the median. Circles outside the boxes represent outliers. Scale bar = 5 µm.

Figure 2.

Representative images of poor synaptic overlap (left) and robust overlap (right) of the motor endplate (red) and nerve terminal (green). Overlap is indicated by yellow. (color online) Scale bar = 5 µm.

Muscle Fiber Size and Composition

Linear mixed effects modeling demonstrated that animal weight was not a significant predictor of fiber size or muscle composition and, therefore, weight was subsequently removed from the regression model. There were no statistically significant effects of age or training on muscle fiber size or composition in either the LTA or MTA (Figure 3). Supplementary Table 2 summarizes MHC fiber type compositions for the LTA, MTA, and plantaris. The LTA was mainly comprised of Type IIb fibers and the MTA of Type IIx fibers, which is consistent with fiber types found in the larynx in previous studies (14,24,36). Type IIa fibers accounted for less than 0.1% of total fibers in the MTA and were not found in the LTA. Type IIL was not found either the MTA or LTA. Co-expression of IIb and IIx fibers were higher in the plantaris relative to both the MTA and LTA.

Figure 3.

Average minimum Feret diameter muscle fiber size for lateral thyroarytenoid (LTA), medial thyroarytenoid (MTA), and plantaris hindlimb. Although there were average increases in the LTA of young animals with training and average decreases in the plantaris hindlimb of young with training, these training differences were not statistically significant. Any differences in responses between muscle type could have to do with individual variability across groups or due to task specificity, where the larynx was exercised more than the limbs. Training effects seemed to have even less impact on the laryngeal and plantaris hindlimb muscles in the older cohort. Box and whisker plots are expressed as medians, interquartile ranges, and outliers.

Ultrasonic Vocalization Acoustics

Number of USVs

Vocal training had a significant effect on the number of vocalizations produced at the post-training time point compared to pre-training (F[2,42] = 9.42; p < .001). The 8-week group increased the number of USVs produced post-training, whereas the control group decreased their number of USVs produced (p < .001). The increase in the 8-week group was greater than the more moderate increase in the 4-week group (p = .04). Age did not have a significant effect on number of vocalizations (F[2,42] = .18; p = .67); there was also not an age by training group interaction (F[2,42] = .30; p = .76).

Duration of USVs (ms)

There was a significant main effect of vocal training (F[2,42] = 14.38; p < .001) on USV duration. The 8-week training group increased their USV duration, whereas the control group decreased USV duration (p < .001). The increased duration in the 8-week was greater than the relatively small increased duration in the 4-week training group (p = 0.01). Age did not have a significant effect on USV duration (F[2,42] = .94; p = .34), nor was there an age by training group interaction (F[2,42] = 1.68; p = .20).

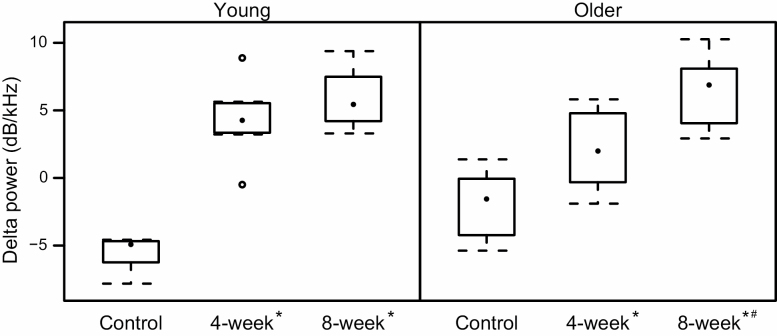

Ultrasonic vocalization intensity (mean power, dB/kHz)

Except for one older rat in the 4-week group, rats in the two training groups all increased the intensity of their USVs; in contrast, all rats in the control groups except for one had a mean decrease in their USV intensity. There was a significant interaction between vocal training and age (F[2,42] = 5.7; p < .001). The overall effect of training was similar in both age groups with increased intensity in the 8-week groups compared to decreased intensity in the control groups in both young (p < .0001) and older (p < .0001) animals as well as increased intensity in the 4-week groups compared to controls in both young (p < .0001) and older (p =.02) animals. The increase in intensity appeared more dose dependent in the older animals, with a significantly greater increase in the 8-week old group compared to the 4-week old group (p = .01). There was no different in intensity between the 4- and 8-week groups in the young animals (p = 1.0).

Average frequencies of USVs (mean kHz)

A main effect of vocal training on average USV frequency was found (F[2,42] = 8.30, p < .001) with a decrease in frequency in the 4-week group (p = .01) and 8-week group (p = .001) relative to an increase in the control group. Age did not have a significant effect on USV frequency (F[2,42] = 1.82, p = .18), nor was there an age by training group interaction for frequency (F[2,42] = .46, p = .63).

Bandwidth (kHz range)

There were no significant main effects of training on USV bandwidth (F[2,42] = 3.01, p = .06). Age (F[2,42] = 1.75, p = .19) and age by training interaction were also non-significant (F[2,42] = 2.82, p = .07).

Ultrasonic vocalization complexity (sinuosity)

A significant interaction between group and age (F[2,42] = 3.39, p = 0.04) on USV complexity was driven by a difference between younger control and older 4-week trained rats (p = .01). This comparison was not related to our experimental question. However, a main effect of training was also found (F[2,42] = 3.53, p = .04) driven by increased complexity in the 8-week training group relative to the control group (p = .048).

Supplementary Table 3 summarizes main effects of USV means and standard deviations by age and training groups; Supplementary Table 4 summarizes means and standard deviations of Age × Training interactions across the same six USV parameters (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Change in ultrasonic vocalization intensity (delta power in dB/kHz) from baseline to post-experiment by experimental group and age. Significant differences within each age group are indicated as follows: * = different than control group; # = different from 4-week group.

Discussion

This study investigated the effects of vocal exercise duration and age on laryngeal neuromuscular structure (NMJ morphology and myofiber size and composition) and function (USV acoustics). Vocal training had a greater influence on laryngeal structure and function than did age. Both young and older trained animals had significantly less NMJ motor endplate dispersion in the LTA, and produced a significantly increased number of USV with longer durations, greater intensities, and decreased USV frequency. In general, these differences were amplified in the longer 8-week training group compared to the 4-week group.

Training Results in Less NMJ Motor Endplate Dispersion

The lesser degree of NMJ motor endplate dispersion corroborates with our previous work demonstrating significantly less motor endplate dispersion in the LTA in both younger and older rats trained to vocalize for 8 weeks (13,14). However, this current study differs from our previous work in several ways. First, significant training effects on motor endplate dispersions and acoustic parameters were seen with 4 weeks of vocal training in the present study but not in previous work (14). Differences across studies could be due to the individualized progression of vocalization targets each rat received for the week in this study as opposed to increasing the same number of vocalizations across the entire training group in previous work by Johnson et al. (13); differences could also be due to the rat strain—the Long-Evans strain was used in previous work by Lenell et al. (14) compared to the F344BN strain used in this study. The implication of these differences across studies is the importance of individualizing exercise programs for optimal training progress.

Another key difference between the current study and previous work was the effect of age on neuromuscular laryngeal structure and function. Ultrasonic vocalization intensity was the only parameter significantly impacted by age in the present study. These findings contrast previous work showing both age and training effects on thyroarytenoid morphology and several USV parameters (13,37). The main reason underlying differences in results between the present study and previous work could be the age of the rats used in the older group. In the present study, 24-month old rats were used for training, while in previous work, rats in the older group were 32 months old (13,37). These findings indicate the importance of studying the effects of vocal training on the laryngeal muscles across the lifespan, not just in cross-sectional designs.

Laryngeal Muscle Fiber Composition and Size Not Significantly Affected by Age or Training

Muscle fiber composition found in the present study was similar to previous work by Lenell and colleagues (2019) (14) , which showed that the LTA was comprised primarily of IIb and the MTA primarily of IIx fibers. In contrast, the present study found no MHC Type IIL fibers in the larynx. Differences in muscle composition across studies may be due to in the strain of rat used for the 2 studies: F344BN (current study) versus Long-Evans (previous work). Of note, although not statistically significant, average fiber size was smaller in plantaris muscle in the older control group compared to the younger control group. These findings align with previous literature on the effects of biological age on the hindlimb muscles (38,39). Reduced variability in average muscle fiber size of the LTA of trained animals in both age groups compared to controls was also observed; reduced variability in fiber size was also seen in the MTA of older trained animals. Variability in fiber sizes in our study parallel previous work demonstrating greater variability in muscle fiber size as fibers within the muscle atrophy at different rates in aged hindlimb muscle (40).

Ultrasonic vocalization Training Changes Laryngeal Function

Increased USV intensity, duration, and complexity from pre-to-post training time points suggest both physiological and functional changes occur in the larynx with vocal training. Work by Riede (15) further confirms these patterns, having previously demonstrated increased laryngeal muscle contraction force and duration underlie USVs produced with greater intensity and complexity of modulated frequencies in communicative calls around 50 kHz. In contrast, untrained rats in the present study decreased their USV intensities over time. Because animals were all single-housed, rats in the control group did not communicate with other rats. Potential translational implication of these findings is that social isolation may negatively impact laryngeal muscle function.

Vocal Training as Endurance Exercise

Neuromuscular junction morphology in the skeletal limb literature has previously shown that while high-intensity endurance training results in greater dispersion of NMJ motor endplates, low-intensity endurance training results in smaller dispersions of NMJ endplates (18). Furthermore, hypertrophic changes in muscle fibers occur with strength training (ie, increased muscle force or power) but not submaximal endurance training (ie, increased muscle stamina with increased duration of use) (41–46). Although there were significant differences in NMJ morphology and greater changes in USV acoustics with vocal training in the present study, neither vocal exercise nor age had any significant effects on laryngeal muscle fiber size or composition. The lack of robust hypertrophic changes within the laryngeal muscle fibers, but presence of more compact NMJ endplates in the vocally trained animals, supports the notion that behavioral USV training is a form of low-intensity endurance training and not strength training. The physiological adaptations found in this study could be similar to physiological changes that occur in the limb muscles with submaximal endurance training, such as with training to run longer distances (↑ duration) at the same speed (↔ intensity) (eg, marathon training) (46).

The translational implications of these findings is that current behavioral vocal training programs for humans with age-related voice decline (dysphonia) may improve vocal muscle endurance and neuromuscular efficiency in the aging larynx (11,12,47). In other words, vocal exercise paradigms currently used in the clinical setting may increase reliability of synaptic transmission from the motor nerve to muscle via the NMJ—and may have less to do with strengthening or increasing the size of the laryngeal muscle fibers.

Future mechanistic studies should focus on altering the intensity of vocalizations, in addition to duration of training, by progressively increasing the mean power of USVs as training targets. High-intensity vocal training may evoke greater NMJ motor endplate expansion and dispersion ratios than seen in the present study with low-intensity vocal training.

Limitations

There were 2 main limitations to the study. The first was that only male rats were used in the experimental design to account for hormonal variability that can occur in female rats. Future work is needed to determine the effects of hormonal fluctuations (if any) on neuromuscular morphology and USV function. The second main limitation was that although delta changes on several USV parameters were observed with vocal exercise training, biochemical analyses were not performed on the laryngeal muscle as a secondary confirmation of training effect on the laryngeal muscle (eg, citrate synthase or succinate dehydrogenase enzyme analysis). In addition to future work on neuromuscular morphology changes with age and USV training, subsequent biochemical and cellular investigations in the peripheral neuromuscular system are needed to investigate the effects of age and vocal training on the laryngeal muscle.

Conclusion

Understanding laryngeal neuromuscular adaptations to vocal training in aged models is an important step towards understanding neuromuscular mechanisms that underlie vocal dysfunction in the aging voice and the impact of vocal training on these mechanisms. Our work demonstrates that vocal training has positive effects on laryngeal NMJ structure and USV acoustics. Greater differences in NMJ and USV parameters at 8 weeks of training compared to 4 weeks suggest longer training may be better for improving vocal function, especially in senescence. Comparisons between the effects of vocal training on the NMJ and muscle fiber type and size have implications for vocal exercise training improving neuromuscular efficiency and endurance and not inducing laryngeal muscle strength or size.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sabah Merchant and Renjie Bing for contributing to data collection and analysis. Images were collected in the Microscopy Core at the NYU School of Medicine.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Deafness and Communication Disorders at the National Institutes of Health (K23DC014517 to AMJ and F31DC017053 to CL).

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- 1. Golub JS, Chen PH, Otto KJ, Hapner E, Johns MM 3rd. Prevalence of perceived dysphonia in a geriatric population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(11):1736–1739. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00915.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roy N, Stemple J, Merrill RM, Thomas L. Epidemiology of voice disorders in the elderly: preliminary findings. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(4):628–633. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e3180306da1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Mahieu HF. Vocal aging and the impact on daily life: a longitudinal study. J Voice. 2004;18(2):193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2003.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mallick AS, Garas G, McGlashan J. Presbylaryngis: a state-of-the-art review. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;27(3):168–177. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clark BC, Manini TM. What is dynapenia? Nutr Burbank Los Angel Cty Calif. 2012;28(5):495–503. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.8.829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clark BC, Manini TM. Sarcopenia ≠ Dynapenia. J Gerontol Ser A. 2008;63(8):829–34. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.8.829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Malmgren LT, Fisher PJ, Bookman LM, Uno T. Age-related changes in muscle fiber types in the human thyroarytenoid muscle: an immunohistochemical and stereological study using confocal laser scanning microscopy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;121(4):441–451. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(99)70235-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sato T, Tauchi H. Age changes in human vocal muscle. Mech Ageing Dev. 1982;18(1):67–74. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(82)90031-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kendall K. Presbyphonia: a review. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;15(3):137–140. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e328166794f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sauder C, Roy N, Tanner K, Houtz DR, Smith ME. Vocal function exercises for presbylaryngis: a multidimensional assessment of treatment outcomes. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2010;119(7):460–467. doi: 10.1177/000348941011900706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lu FL, Presley S, Lammers B. Efficacy of intensive phonatory-respiratory treatment (LSVT) for presbyphonia: two case reports. J Voice. 2013;27(6):786.e11–786.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2013.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tay EY, Phyland DJ, Oates J. The effect of vocal function exercises on the voices of aging community choral singers. J Voice. 2012;26(5):672.e19–672.e27. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2011.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johnson AM, Ciucci MR, Connor NP. Vocal training mitigates age-related changes within the vocal mechanism in old rats. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(12):1458–1468. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lenell C, Newkirk B, Johnson AM. Laryngeal neuromuscular response to short- and long-term vocalization training in young male rats. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2019;62(2):247–56. doi: 10.1044/2018_JSLHR-S-18-0316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Riede T. Subglottal pressure, tracheal airflow, and intrinsic laryngeal muscle activity during rat ultrasound vocalization. J Neurophysiol. 2011;106(5):2580–2592. doi: 10.1152/jn.00478.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Konopka AR, Harber MP. Skeletal muscle hypertrophy after aerobic exercise training. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2014;42(2):53–61. doi: 10.1249/JES.0000000000000007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ogawa S, Yakabe M, Akishita M. Age-related sarcopenia and its pathophysiological bases. Inflamm Regen. 2016;36(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s41232-016-0022-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Deschenes MR, Maresh CM, Crivello JF, Armstrong LE, Kraemer WJ, Covault J. The effects of exercise training of different intensities on neuromuscular junction morphology. J Neurocytol. 1993;22(8):603–615. doi: 10.1007/BF01181487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Martins RHG, Gonçalvez TM, Pessin ABB, Branco A. Aging voice: presbyphonia. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2014;26(1):1–5. doi: 10.1007/s40520-013-0143-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Basken JN, Connor NP, Ciucci MR. Effect of aging on ultrasonic vocalizations and laryngeal sensorimotor neurons in rats. Exp Brain Res. 2012;219(3):351–361. doi: 10.1007/s00221-012-3096-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marcondes FK, Bianchi FJ, Tanno AP. Determination of the estrous cycle phases of rats: some helpful considerations. Braz J Biol. 2002;62(4A):609–614. doi: 10.1590/s1519-69842002000400008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Panksepp J, Burgdorf J. 50-kHz chirping (laughter?) in response to conditioned and unconditioned tickle-induced reward in rats: effects of social housing and genetic variables. Behav Brain Res. 2000;115(1):25–38. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00238-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ciucci MR, Vinney L, Wahoske EJ, Connor NP. A translational approach to vocalization deficits and neural recovery after behavioral treatment in Parkinson disease. J Commun Disord. 2010;43(4):319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2010.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lenell C, Johnson AM. Sexual dimorphism in laryngeal muscle fibers and ultrasonic vocalizations in the adult rat. Laryngoscope. 2017;127(8):E270–E276. doi: 10.1002/lary.26561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pitman MJ, Berzofsky CE, Alli O, Sharma S. Embryologic innervation of the rat laryngeal musculature—a model for investigation of recurrent laryngeal nerve reinnervation. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(12):3117–3126. doi: 10.1002/lary.24216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Alshuaib WB, Fahim MA. Effect of exercise on physiological age-related change at mouse neuromuscular junctions. Neurobiol Aging. 1990;11(5):555–561. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(90)90117-i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Andonian MH, Fahim MA. Endurance exercise alters the morphology of fast- and slow-twitch rat neuromuscular junctions. Int J Sports Med. 1988;09(3):218–23. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1025009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Johnson AM, Connor NP. Effects of electrical stimulation on neuromuscular junction morphology in the aging rat tongue. Muscle Nerve. 2011;43(2):203–211. doi: 10.1002/mus.21819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Deschenes MR, Sherman EG, Roby MA, Glass EK, Harris MB. Effect of resistance training on neuromuscular junctions of young and aged muscles featuring different recruitment patterns. J Neurosci Res. 2015;93(3):504–513. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bloemberg D, Quadrilatero J. Rapid determination of myosin heavy chain expression in rat, mouse, and human skeletal muscle using multicolor immunofluorescence analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kumar A, Accorsi A, Rhee Y, Girgenrath M. Do’s and don’ts in the preparation of muscle cryosections for histological analysis. J Vis Exp. 2015;(99):e52793. doi: 10.3791/52793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Smith LR, Barton ER. SMASH—semi-automatic muscle analysis using segmentation of histology: a MATLAB application. Skelet Muscle. 2014;4:21. doi: 10.1186/2044-5040-4-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pertl C, Eblenkamp M, Pertl A, et al. A new web-based method for automated analysis of muscle histology. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bright PL, Nelson RM. A capacity-based approach for addressing ancillary care needs: implications for research in resource limited settings. J Med Ethics. 2012;38(11):672–676. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2011-100205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Coffey KR, Marx RG, Neumaier JF. DeepSqueak: a deep learning-based system for detection and analysis of ultrasonic vocalizations. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44(5):859–868. doi: 10.1038/s41386-018-0303-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rhee HS, Lucas CA, Hoh JF. Fiber types in rat laryngeal muscles and their transformations after denervation and reinnervation. J Histochem Cytochem. 2004;52(5):581–590. doi: 10.1177/002215540405200503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kletzien H, Russell JA, Connor NP. The effects of treadmill running on aging laryngeal muscle structure. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(3):672–7. doi: 10.1002/lary.25520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Holloszy JO, Chen M, Cartee GD, Young JC. Skeletal muscle atrophy in old rats: differential changes in the three fiber types. Mech Ageing Dev. 1991;60(2):199–213. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(91)90131-i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Barnouin Y, McPhee JS, Butler-Browne G, et al. Coupling between skeletal muscle fiber size and capillarization is maintained during healthy aging. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2017;8(4):647–659. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kano Y, Shimegi S, Furukawa H, Matsudo H, Mizuta T. Effects of aging on capillary number and luminal size in rat soleus and plantaris muscles. J Gerontol Ser A. 2002;57(12):B422–7. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.12.B422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hughes DC, Ellefsen S, Baar K. Adaptations to endurance and strength training. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018;8(6):a029769. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a029769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lüthi JM, Howald H, Claassen H, Rösler K, Vock P, Hoppeler H. Structural changes in skeletal muscle tissue with heavy-resistance exercise. Int J Sports Med. 1986;7(3):123–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1025748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McDonagh MJN, Davies CTM. Adaptive response of mammalian skeletal muscle to exercise with high loads. Eur J Appl Physiol. 1984;52(2):139–55. doi: 10.1007/BF004333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Houston ME, Froese EA, Valeriote STP, Green HJ, Ranney DA. Muscle performance, morphology and metabolic capacity during strength training and detraining: a one leg model. Eur J Appl Physiol. 1983;51(1):25–35. doi: 10.1007/BF00952534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Staron RS, Malicky ES, Leonardi MJ, Falkel JE, Hagerman FC, Dudley GA. Muscle hypertrophy and fast fiber type conversions in heavy resistance-trained women. Eur J Appl Physiol. 1990;60(1):71–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00572189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lieber RL, Roberts TJ, Blemker SS, Lee SSM, Herzog W. Skeletal muscle mechanics, energetics and plasticity. J NeuroEngineering Rehabil [Internet]. 2017;14(1):1–16 [cited April 9, 2019]. http://jneuroengrehab.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12984-017-0318-y. doi: 10.1186/s12984-017-0318-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ziegler A, Abbott KV, Johns M, Klein A, Hapner ER. Preliminary data on two voice therapy interventions in the treatment of presbyphonia. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(8):1869–76. doi: 10.1002/lary.24548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.