Abstract

Purpose

Since 2007, the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG) has collected cycle‐based data for assisted reproductive technology (ART) in an online registry. Here, we present the characteristics and treatment outcomes of ART cycles registered during 2018.

Methods

The Japanese ART registry consists of cycle‐specific information for all ART treatment cycles implemented at 621 participating facilities. We conducted descriptive analyses for such cycles registered for 2018.

Results

In total, 454 893 treatment cycles and 56 979 neonates were reported in 2018: both increased from 2017. The mean maternal age was 38.0 years (standard deviation ± 4.7). Of 247 402 oocyte retrievals, 118 378 (47.8%) involved freeze‐all‐embryos cycles; fresh embryo transfer (ET) was performed in 50 463 cycles: a decreasing trend since 2015. A total of 199 914 frozen‐thawed ET cycles were reported, resulting in 69 357 pregnancies and 49 360 neonates born. Single ET (SET) was performed in 82.2% of fresh transfers and 83.4% of frozen‐thawed cycles, with singleton pregnancy/live birth rates of 97.2%/97.2% and 97.0%/97.2%, respectively.

Conclusions

Total ART cycles and subsequent live births increased in 2018. SET was performed in over 80% of cases, and the mode of ET has shifted continuously from using fresh embryos to frozen‐thawed ones compared with previous years.

Keywords: ART registry, freeze‐all strategy, in vitro fertilization, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology

1. INTRODUCTION

Since the first baby in Japan conceived as a result of in vitro fertilization (IVF) was born in 1983, the number of assisted reproductive technology (ART) cycles has increased dramatically each year. According to the latest preliminary report from the International Committee Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technologies for ART worldwide in 2016, Japan was the second largest user of ART worldwide in terms of the annual total number of treatment cycles performed. 1

Because it is essential to monitor the trend and situations of ART treatments implemented in our country, in 1986 the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG) began an ART registry system and launched an online registration system in 2007. Since then, cycle‐specific information for all ART treatment cycles performed in ART facilities has been collected. The aim of this report is to describe the characteristics and treatment outcomes of registered ART cycles during 2018 in comparison with previous years. 2

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Since 2007, the JSOG has requested all participating ART clinics and hospitals to register cycle‐specific information for all ART treatment cycles. The information includes patient characteristics, information on the specific ART treatment, and pregnancy and obstetric outcomes. Detailed information collected in the registry has been reported previously. 3 For ART cycles performed between January 1, 2018, and December 31, 2018, the JSOG requested registration of the information via an online registry system by the end of November 2019.

Using the registry data for 2018, we performed a descriptive analysis to investigate the characteristics and treatment outcomes of registered cycles. First, the numbers of registered cycles for the initiation of treatment, oocyte retrievals, fresh embryo transfer (ET) cycles, freeze‐all‐embryos/oocytes cycles (henceforth “freeze‐all”), frozen‐thawed embryo transfer (FET) cycles, pregnancies, and neonates were compared with those in previous years. Second, the characteristics of registered cycles and treatment outcomes were described for fresh and FET cycles. Fresh cycles were stratified according to fertilization method including IVF, intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), gamete intrafallopian transfer (GIFT), and included cycles with oocyte freezing based on medical indications. Treatment outcomes included pregnancy, miscarriage, and live birth rates, multiple pregnancies defined according to the numbers of gestational sacs in utero and of neonates. Pregnancy outcomes included ectopic pregnancy, heterotopic pregnancy, artificially induced abortion, stillbirth, and fetal reduction. Third, the treatment outcomes of pregnancy, live birth, miscarriage, and multiple pregnancy rates were analyzed according to patient age. Last, we also recorded the treatment outcomes for FET cycles using frozen‐thawed oocytes based on medical indications.

3. RESULTS

In Japan, there were 622 registered ART facilities in 2018, of which 621 participated in the ART registration system. A total of 592 registered facilities actually implemented some form of ART treatment in 2018 while 29 did not. Trends in the numbers of registered cycles, oocyte retrievals, pregnancies, and neonates born as a result of IVF, ICSI, and FET cycles from 1985 to 2018 are shown in Table 1. In 2018, 454 893 cycles were registered and 56 979 neonates were recorded. The total number of registered cycles for fresh IVF and ICSI followed by ET had decreased from the previous year in 2017. However, in 2018, the registered cycles and oocyte retrieval cycles increased from 2017 both for IVF and ICSI. Among registered fresh ET cycles, 63.2% were ICSI. The numbers of freeze‐all cycles increased both in IVF and ICSI cycles, so the numbers of neonates born after fresh ET cycles have been decreasing because of fewer such treatments. In contrast, the number of FET cycles increased continuously; in 2018, there were 203 482 (a 2.2% increase from 2017), resulting in 69 395 pregnancies and 49 383 neonates.

TABLE 1.

Trends in numbers of registered cycles, oocyte retrievals, pregnancies and neonates according to IVF, ICSI, and frozen‐thawed embryo transfer cycles, Japan, 1985‐2018

| Year | Fresh cycles | FET cycles c | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVF a | ICSI b | |||||||||||||||

| No. of registered cycles | No. of egg retrieval | No. of freeze‐all cycles | No. of ET cycles | No. of cycles with pregnancy | No. of neonates | No. of registered cycles | No. of oocyte retrievals | No. of freeze‐all cycles | No. of ET cycles | No. of cycles with pregnancy | No. of neonates | No. of registered cycles | No. of ET cycles | No. of cycles with pregnancy | No. of neonates | |

| 1985 | 1195 | 1195 | 862 | 64 | 27 | |||||||||||

| 1986 | 752 | 752 | 556 | 56 | 16 | |||||||||||

| 1987 | 1503 | 1503 | 1070 | 135 | 54 | |||||||||||

| 1988 | 1702 | 1702 | 1665 | 257 | 114 | |||||||||||

| 1989 | 4218 | 3890 | 2968 | 580 | 446 | 184 | 92 | 7 | 3 | |||||||

| 1990 | 7405 | 6892 | 5361 | 1178 | 1031 | 160 | 153 | 17 | 17 | |||||||

| 1991 | 11 177 | 10 581 | 8473 | 2015 | 1661 | 369 | 352 | 57 | 39 | |||||||

| 1992 | 17 404 | 16 381 | 12 250 | 2702 | 2525 | 963 | 936 | 524 | 42 | 35 | 553 | 530 | 79 | 66 | ||

| 1993 | 21 287 | 20 345 | 15 565 | 3730 | 3334 | 2608 | 2447 | 1271 | 176 | 149 | 681 | 597 | 86 | 71 | ||

| 1994 | 25 157 | 24 033 | 18 690 | 4069 | 3734 | 5510 | 5339 | 4114 | 759 | 698 | 1303 | 1112 | 179 | 144 | ||

| 1995 | 26 648 | 24 694 | 18 905 | 4246 | 3810 | 9820 | 9054 | 7722 | 1732 | 1579 | 1682 | 1426 | 323 | 298 | ||

| 1996 | 27 338 | 26 385 | 21 492 | 4818 | 4436 | 13 438 | 13 044 | 11 269 | 2799 | 2588 | 2900 | 2676 | 449 | 386 | ||

| 1997 | 32 247 | 30 733 | 24 768 | 5730 | 5060 | 16 573 | 16 376 | 14 275 | 3495 | 3249 | 5208 | 4958 | 1086 | 902 | ||

| 1998 | 34 929 | 33 670 | 27 436 | 6255 | 5851 | 18 657 | 18 266 | 15 505 | 3952 | 3701 | 8132 | 7643 | 1748 | 1567 | ||

| 1999 | 36 085 | 34 290 | 27 455 | 6812 | 5870 | 22 984 | 22 350 | 18 592 | 4702 | 4247 | 9950 | 9093 | 2198 | 1812 | ||

| 2000 | 31 334 | 29 907 | 24 447 | 6328 | 5447 | 26 712 | 25 794 | 21 067 | 5240 | 4582 | 11 653 | 10 719 | 2660 | 2245 | ||

| 2001 | 32 676 | 31 051 | 25 143 | 6749 | 5829 | 30 369 | 29 309 | 23 058 | 5924 | 4862 | 13 034 | 11 888 | 3080 | 2467 | ||

| 2002 | 34 953 | 33 849 | 26 854 | 7767 | 6443 | 34 824 | 33 823 | 25 866 | 6775 | 5486 | 15 887 | 14 759 | 4094 | 3299 | ||

| 2003 | 38 575 | 36 480 | 28 214 | 8336 | 6608 | 38 871 | 36 663 | 27 895 | 7506 | 5994 | 24 459 | 19 641 | 6205 | 4798 | ||

| 2004 | 41 619 | 39 656 | 29 090 | 8542 | 6709 | 44 698 | 43 628 | 29 946 | 7768 | 5921 | 30 287 | 24 422 | 7606 | 5538 | ||

| 2005 | 42 822 | 40 471 | 29 337 | 8893 | 6706 | 47 579 | 45 388 | 30 983 | 8019 | 5864 | 35 069 | 28 743 | 9396 | 6542 | ||

| 2006 | 44 778 | 42 248 | 29 440 | 8509 | 6256 | 52 539 | 49 854 | 32 509 | 7904 | 5401 | 42 171 | 35 804 | 11 798 | 7930 | ||

| 2007 | 53 873 | 52 165 | 7626 | 28 228 | 7416 | 5144 | 61 813 | 60 294 | 11 541 | 34 032 | 7784 | 5194 | 45 478 | 43 589 | 13 965 | 9257 |

| 2008 | 59 148 | 57 217 | 10 139 | 29 124 | 6897 | 4664 | 71 350 | 69 864 | 15 390 | 34 425 | 7017 | 4615 | 60 115 | 57 846 | 18 597 | 12 425 |

| 2009 | 63 083 | 60 754 | 11 800 | 28 559 | 6891 | 5046 | 76 790 | 75 340 | 19 046 | 35 167 | 7330 | 5180 | 73 927 | 71 367 | 23 216 | 16 454 |

| 2010 | 67 714 | 64 966 | 13 843 | 27 905 | 6556 | 4657 | 90 677 | 88 822 | 24 379 | 37 172 | 7699 | 5277 | 83 770 | 81 300 | 27 382 | 19 011 |

| 2011 | 71 422 | 68 651 | 16 202 | 27 284 | 6341 | 4546 | 102 473 | 100 518 | 30 773 | 38 098 | 7601 | 5415 | 95 764 | 92 782 | 31 721 | 22 465 |

| 2012 | 82 108 | 79 434 | 20 627 | 29 693 | 6703 | 4740 | 125 229 | 122 962 | 41 943 | 40 829 | 7947 | 5498 | 119 089 | 116 176 | 39 106 | 27 715 |

| 2013 | 89 950 | 87 104 | 25 085 | 30 164 | 6817 | 4776 | 134 871 | 134 871 | 49 316 | 41 150 | 8027 | 5630 | 141 335 | 138 249 | 45 392 | 32 148 |

| 2014 | 92 269 | 89 397 | 27 624 | 30 414 | 6970 | 5025 | 144 247 | 141 888 | 55 851 | 41 437 | 8122 | 5702 | 157 229 | 153 977 | 51 458 | 36 595 |

| 2015 | 93 614 | 91 079 | 30 498 | 28 858 | 6478 | 4629 | 155 797 | 153 639 | 63 660 | 41 396 | 8169 | 5761 | 174 740 | 171 495 | 56 888 | 40 611 |

| 2016 | 94 566 | 92 185 | 34 188 | 26 182 | 5903 | 4266 | 161 262 | 159 214 | 70 387 | 38 315 | 7324 | 5166 | 191 962 | 188 338 | 62 749 | 44 678 |

| 2017 | 91 516 | 89 447 | 36 441 | 22 423 | 5182 | 3731 | 157 709 | 155 758 | 74 200 | 33 297 | 6757 | 4826 | 198 985 | 195 559 | 67 255 | 48 060 |

| 2018 | 92 552 | 90 376 | 38 882 | 20 894 | 4755 | 3402 | 158 859 | 157 026 | 79 496 | 29 569 | 5886 | 4194 | 203 482 | 200 050 | 69 395 | 49 383 |

Abbreviations: ET, embryo transfer; FET, Frozen‐thawed embryo transfer; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection; IVF, in vitro fertilization.

Including gamete intrafallopian transfer.

Including split‐ICSI cycles.

Including cycles using frozen‐thawed oocytes.

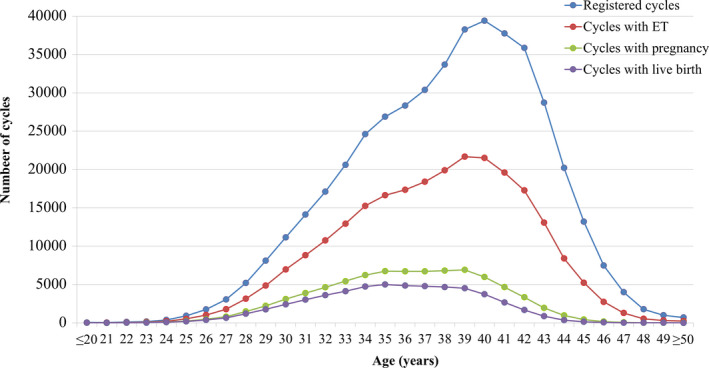

The distributions of patient age in registered cycles and different subgroups of cycles with ET, pregnancy, and live births are shown in Figure 1. The mean patient age for registered cycles was 38.0 years (standard deviation [SD] ±4.7), and 41.8% of registered cycles were for women in their 40s; the mean age for pregnancy and live birth cycles was 36.0 years (SD ± 4.1) and 35.6 years (SD ± 4.0), respectively.

FIGURE 1.

Age distributions of all registered cycles, different subgroups of cycles for ET, pregnancy, and live birth in 2018. Adapted from the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology ART Databook 2018 (http://plaza.umin.ac.jp/~jsog‐art/2018data_20201001.pdf). ET, embryo transfer

The detailed characteristics and treatment outcomes of registered fresh cycles are shown in Table 2. There were 88 072 registered IVF cycles, 28 546 split‐ICSI cycles, 127 974 ICSI cycles using ejaculated spermatozoa, 2339 ICSI cycles using testicular sperm extraction (TESE), 25 GIFT cycles, 644 cycles for oocyte freezing based on medical indications, and 3811 other cycles. Of the 247 402 cycles with oocyte retrieval, 118 378 (47.8%) were freeze‐all cycles. The pregnancy rate per ET was 22.8% for IVF and 18.7% for ICSI using ejaculated spermatozoa. Single ET was performed at a rate of 82.2%, with a pregnancy rate of 21.4%. Live birth rates per ET were 15.9% for IVF, 12.7% for ICSI using ejaculated spermatozoa, and 11.3% for ICSI with TESE. The singleton pregnancy rate and live birth rate were 97.2% and 97.2%, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics and treatment outcomes of registered fresh ART cycles in assisted reproductive technology, Japan, 2018

| Variables | IVF–ET | Split | ICSI | GIFT | Frozen oocyte | Others a | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ejaculated sperm | TESE | |||||||

| No. of registered cycles | 88 072 | 28 546 | 127 974 | 2339 | 25 | 644 | 3811 | 251 411 |

| No. of egg retrieval | 86 021 | 28 267 | 126 422 | 2337 | 25 | 638 | 3692 | 247 402 |

| No. of fresh ET cycles | 20 403 | 5058 | 23 981 | 530 | 25 | 0 | 466 | 50 463 |

| No. of freeze‐all‐embryos | 37 116 | 19 728 | 58 454 | 1314 | 0 | 538 | 1228 | 118 378 |

| No. of cycles with pregnancy | 4648 | 1310 | 4487 | 89 | 4 | 0 | 103 | 10 641 |

| Pregnancy rate per ET | 22.8% | 25.9% | 18.7% | 16.8% | 16.0% | ‐ | 22.1% | 21.1% |

| Pregnancy rate per egg retrieval | 5.4% | 4.6% | 3.6% | 3.8% | 16.0% | ‐ | 2.8% | 4.3% |

| Pregnancy rate per egg retrieval excluding freeze‐all‐embryos | 9.5% | 15.3% | 6.6% | 8.7% | 16.0% | ‐ | 4.2% | 8.3% |

| SET cycles | 17 014 | 4449 | 19 292 | 340 | 2 | ‐ | 402 | 41 499 |

| Pregnancy following SET cycles | 3933 | 1176 | 3624 | 58 | 0 | ‐ | 92 | 8883 |

| Rate of SET cycles | 83.4% | 88.0% | 80.5% | 64.2% | 8.0% | ‐ | 86.3% | 82.2% |

| Pregnancy rate following SET cycles | 23.1% | 26.4% | 18.8% | 17.1% | 0.0% | ‐ | 22.9% | 21.4% |

| Miscarriages | 1161 | 273 | 1229 | 28 | 0 | ‐ | 20 | 2711 |

| Miscarriage rate per pregnancy | 25.0% | 20.8% | 27.4% | 31.5% | 0.0% | ‐ | 19.4% | 25.5% |

| Singleton pregnancies b | 4408 | 1256 | 4247 | 85 | 3 | ‐ | 98 | 10 097 |

| Multiple pregnancies b | 113 | 29 | 143 | 1 | 0 | ‐ | 3 | 289 |

| Twin pregnancies b | 109 | 29 | 142 | 1 | 0 | ‐ | 3 | 284 |

| Triplet pregnancies b | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ‐ | 0 | 5 |

| Quadruplet pregnancies b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ‐ | 0 | 0 |

| Multiple pregnancy rate b | 2.5% | 2.3% | 3.6% | 1.2% | 0.0% | ‐ | 3.0% | 2.8% |

| Live births | 3246 | 965 | 3045 | 60 | 3 | ‐ | 78 | 7397 |

| Live birth rate per ET | 15.9% | 19.1% | 12.7% | 11.3% | 12.0% | ‐ | 16.7% | 14.7% |

| Total number of neonates | 3319 | 983 | 3150 | 61 | 3 | ‐ | 80 | 7596 |

| Singleton live births | 3164 | 947 | 2926 | 59 | 3 | ‐ | 76 | 7175 |

| Twin live births | 76 | 18 | 112 | 1 | 0 | ‐ | 2 | 209 |

| Triplet live births | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ‐ | 0 | 1 |

| Quadruplet live births | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ‐ | 0 | 0 |

| Pregnancy outcomes | ‐ | |||||||

| Ectopic pregnancies | 59 | 20 | 56 | 0 | 1 | ‐ | 1 | 137 |

| Heterotopic pregnancy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ‐ | 0 | 0 |

| Artificial abortions | 25 | 5 | 25 | 1 | 0 | ‐ | 1 | 57 |

| Still births | 18 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 0 | ‐ | 0 | 27 |

| Fetal reductions | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ‐ | 0 | 1 |

| Unknown cycles for pregnancy outcomes | 104 | 32 | 121 | 0 | 0 | ‐ | 3 | 260 |

Abbreviations: ET, embryo transfer; GIFT, gamete intrafallopian transfer; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection; IVF–ET; in vitro fertilization‐embryo transfer; SET, single embryo transfer; TESE, testicular sperm extraction.

Others including zygote intrafallopian transfer (ZIFT).

Singleton, twin, triplet and quadruplet pregnancies were defined according to the numbers of gestational sacs in utero.

The characteristics and treatment outcomes of FET cycles are shown in Table 3. There were 203 246 registered cycles, among which FET was performed in 199 914, leading to 69 357 pregnancies (pregnancy rate per FET = 34.7%). The miscarriage rate per pregnancy was 25.5%, resulting in a 24.1% live birth rate per ET. Single ET was performed at a rate of 84.4%, and the singleton pregnancy and live birth rates were 97.0% and 97.2%, respectively.

TABLE 3.

Characteristics and treatment outcomes of FET cycles in ART clinics in Japan for 2018

| Variables | FET | Others a | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of registered cycles | 202 229 | 1017 | 203 246 |

| No. of FET | 199 022 | 892 | 199 914 |

| No. of cycles with pregnancy | 69 072 | 285 | 69 357 |

| Pregnancy rate per FET | 34.7% | 32.0% | 34.7% |

| SET cycles | 167 898 | 743 | 168 641 |

| Pregnancy following SET cycles | 59 899 | 242 | 60 141 |

| Rate of SET cycles | 84.4% | 83.3% | 83.4% |

| Pregnancy rate following SET cycles | 35.7% | 32.6% | 35.7% |

| Miscarriages | 17 601 | 69 | 17 670 |

| Miscarriage rate per pregnancy | 25.5% | 24.2% | 25.5% |

| Singleton pregnancies b | 65 556 | 266 | 65 822 |

| Multiple pregnancies b | 2015 | 9 | 2024 |

| Twin pregnancies b | 1980 | 8 | 1988 |

| Triplet pregnancies b | 31 | 1 | 32 |

| Quadruplet pregnancies b | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Multiple pregnancy rate b | 3.0% | 3.3% | 3.0% |

| Live births | 47 873 | 208 | 48 081 |

| Live birth rate per FET | 24.1% | 23.3% | 24.1% |

| Total number of neonates | 49 148 | 212 | 49 360 |

| Singleton live births | 46 432 | 200 | 46 632 |

| Twin live births | 1335 | 6 | 1341 |

| Triplet live births | 14 | 0 | 14 |

| Quadruplet live births | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Pregnancy outcomes | |||

| Ectopic pregnancies | 350 | 1 | 351 |

| Heterotopic pregnancy | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Artificial abortions | 272 | 0 | 272 |

| Still births | 236 | 1 | 237 |

| Fetal reduction | 16 | 0 | 16 |

| Unknown cycles for pregnancy outcomes | 1999 | 3 | 2002 |

Abbreviations: FET, frozen‐thawed embryo transfer; SET, single embryo transfer.

Including cycles using frozen‐thawed oocyte.

Singleton, twin, triplet and quadruplet pregnancies were defined according to the numbers of gestational sacs in utero.

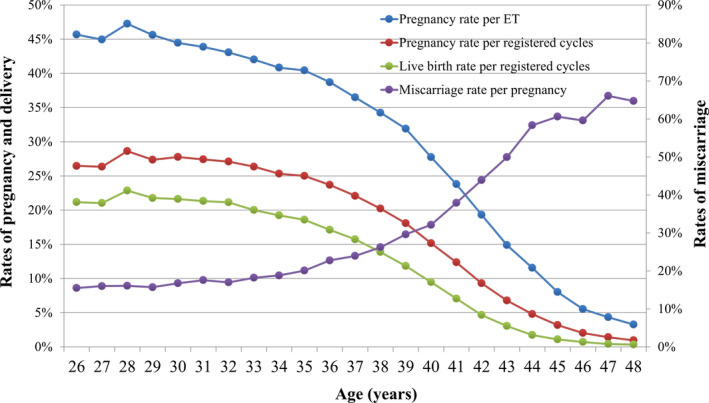

Treatment outcomes of registered cycles, including pregnancy, miscarriage, live birth, and multiple pregnancy rates, according to maternal age, are shown in Table 4. Similarly, the distribution of pregnancy, live birth, and miscarriage rates according to maternal age are shown in Figure 2. The pregnancy rate per ET exceeded 40% up to 35 years of age; this rate gradually fell below 30% after age 40 and below 10% after age 45. The miscarriage rate was below 20% under age 35 years but gradually increased to 32.1% and 49.9% for those aged 40 and 43 years, respectively. The live birth rate per registered cycle was around 20% up to 33 years of age and decreased to 9.5% and 3.1% at ages 40 and 43 years, respectively. Multiple pregnancy rates varied between 2% and 3% across most age groups.

TABLE 4.

Treatment outcomes of registered cycles according to patient age, Japan, 2018

| Age (years) | No. of registered cycles | No. of ET cycles | Pregnancy | Multiple pregnancies a | Miscarriage | Live birth | Pregnancy rate per ET | Pregnancy rate per registered cycles | Live birth rate per registered cycles | Miscarriage rate per pregnancy | Multiple pregnancy rate a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤20 | 49 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 50.0% | 6.1% | 6.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 21 | 29 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12.5% | 3.4% | 3.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 22 | 103 | 48 | 22 | 2 | 3 | 16 | 45.8% | 21.4% | 15.5% | 13.6% | 9.5% |

| 23 | 155 | 79 | 35 | 2 | 5 | 26 | 44.3% | 22.6% | 16.8% | 14.3% | 5.7% |

| 24 | 384 | 205 | 98 | 1 | 15 | 82 | 47.8% | 25.5% | 21.4% | 15.3% | 1.0% |

| 25 | 926 | 514 | 231 | 0 | 33 | 177 | 44.9% | 24.9% | 19.1% | 14.3% | 0.0% |

| 26 | 1757 | 1018 | 465 | 18 | 72 | 372 | 45.7% | 26.5% | 21.2% | 15.5% | 4.0% |

| 27 | 3037 | 1780 | 800 | 13 | 128 | 639 | 44.9% | 26.3% | 21.0% | 16.0% | 1.7% |

| 28 | 5199 | 3148 | 1488 | 32 | 239 | 1188 | 47.3% | 28.6% | 22.9% | 16.1% | 2.2% |

| 29 | 8098 | 4859 | 2216 | 74 | 348 | 1763 | 45.6% | 27.4% | 21.8% | 15.7% | 3.4% |

| 30 | 11 128 | 6951 | 3090 | 92 | 518 | 2407 | 44.5% | 27.8% | 21.6% | 16.8% | 3.0% |

| 31 | 14 116 | 8826 | 3872 | 100 | 680 | 3011 | 43.9% | 27.4% | 21.3% | 17.6% | 2.6% |

| 32 | 17 101 | 10 755 | 4632 | 117 | 786 | 3615 | 43.1% | 27.1% | 21.1% | 17.0% | 2.6% |

| 33 | 20 594 | 12 921 | 5428 | 135 | 987 | 4122 | 42.0% | 26.4% | 20.0% | 18.2% | 2.6% |

| 34 | 24 600 | 15 257 | 6229 | 176 | 1171 | 4732 | 40.8% | 25.3% | 19.2% | 18.8% | 2.9% |

| 35 | 26 892 | 16 639 | 6727 | 211 | 1350 | 5002 | 40.4% | 25.0% | 18.6% | 20.1% | 3.2% |

| 36 | 28 339 | 17 346 | 6714 | 252 | 1528 | 4848 | 38.7% | 23.7% | 17.1% | 22.8% | 3.8% |

| 37 | 30 377 | 18 393 | 6711 | 197 | 1606 | 4778 | 36.5% | 22.1% | 15.7% | 23.9% | 3.0% |

| 38 | 33 679 | 19 893 | 6813 | 217 | 1787 | 4670 | 34.2% | 20.2% | 13.9% | 26.2% | 3.3% |

| 39 | 38 256 | 21 684 | 6917 | 203 | 2049 | 4521 | 31.9% | 18.1% | 11.8% | 29.6% | 3.0% |

| 40 | 39 410 | 21 510 | 5969 | 162 | 1918 | 3733 | 27.7% | 15.1% | 9.5% | 32.1% | 2.8% |

| 41 | 37 736 | 19 608 | 4664 | 126 | 1768 | 2665 | 23.8% | 12.4% | 7.1% | 37.9% | 2.8% |

| 42 | 35 860 | 17 285 | 3339 | 91 | 1465 | 1674 | 19.3% | 9.3% | 4.7% | 43.9% | 2.8% |

| 43 | 28 715 | 13 072 | 1946 | 57 | 972 | 877 | 14.9% | 6.8% | 3.1% | 49.9% | 3.0% |

| 44 | 20 212 | 8397 | 970 | 29 | 566 | 350 | 11.6% | 4.8% | 1.7% | 58.4% | 3.1% |

| 45 | 13 187 | 5235 | 419 | 5 | 254 | 145 | 8.0% | 3.2% | 1.1% | 60.6% | 1.2% |

| 46 | 7480 | 2740 | 151 | 2 | 90 | 54 | 5.5% | 2.0% | 0.7% | 59.6% | 1.4% |

| 47 | 3994 | 1289 | 56 | 1 | 37 | 17 | 4.3% | 1.4% | 0.4% | 66.1% | 1.9% |

| 48 | 1776 | 522 | 17 | 1 | 11 | 6 | 3.3% | 1.0% | 0.3% | 64.7% | 6.3% |

| 49 | 999 | 301 | 8 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 2.7% | 0.8% | 0.3% | 62.5% | 0.0% |

| ≥50 | 705 | 224 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2.2% | 0.7% | 0.3% | 20.0% | 0.0% |

Abbreviation: ET, embryo transfer.

Multiple pregnancies were defined according to the numbers of gestational sacs in utero.

FIGURE 2.

Pregnancy, live birth, and miscarriage rates, according to patient age, among all registered cycles in 2018. Adapted from the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology ART Databook 2018 (http://plaza.umin.ac.jp/~jsog‐art/2018data_20201001.pdf). ET, embryo transfer

The treatment outcomes of cycles using frozen‐thawed oocytes based on medical indications are shown in Table 5. There were 136 such FET cycles, among which 38 cycles resulted in a pregnancy (pregnancy rate per FET = 27.9%). The miscarriage rate per pregnancy was 29.0%, resulting in a 15.4% live birth rate per ET.

TABLE 5.

Treatment outcomes of embryo transfers using frozen‐thawed oocytes based on medical indications in ART clinics in Japan, 2018

| Variables | Embryo transfer using frozen‐thawed oocytes |

|---|---|

| No. of registered cycles | 236 |

| No. of ET | 136 |

| No. of cycles with pregnancy | 38 |

| Pregnancy rate per ET | 27.9% |

| SET cycles | 91 |

| Pregnancy following SET cycles | 22 |

| Rate of SET cycles | 66.9% |

| Pregnancy rate following SET cycles | 24.2% |

| Miscarriages | 11 |

| Miscarriage rate per pregnancy | 29.0% |

| Singleton pregnancies a | 30 |

| Multiple pregnancies a | 4 |

| Twin pregnancies a | 4 |

| Triplet pregnancies a | 0 |

| Quadruplet pregnancies a | 0 |

| Multiple pregnancy rate a | 11.8% |

| Live births | 21 |

| Live birth rate per ET | 15.4% |

| Total number of neonates | 23 |

| Singleton live births | 19 |

| Twin live births | 2 |

| Triplet live births | 0 |

| Quadruplet live births | 0 |

| Pregnancy outcomes | |

| Ectopic pregnancies | 0 |

| Heterotopic pregnancy | 0 |

| Artificial abortions | 0 |

| Still births | 0 |

| Fetal reduction | 0 |

| Unknown cycles for pregnancy outcomes | 2 |

Abbreviations: ET, embryo transfer; SET, single embryo transfer.

Singleton, twin, triplet and quadruplet pregnancies were defined according to the numbers of gestational sacs in utero.

4. DISCUSSION

Using the current Japanese ART registry system for JSOG, there were 454 893 registered ART cycles and 56 979 resultant neonates, The total number of initiated fresh cycles (both IVF and ICSI) increased from the previous year. Freeze‐all cycles predominated, accounting for 47.8% of all initiated fresh cycles. The single ET rate was 82.2% for fresh transfers and 83.4% for frozen‐thawed cycles, which also showed an increasing trend since 2007, reaching a singleton live birth rate of 97% in total. These results represent the latest clinical practice of ART in Japan.

Advanced age for women receiving ART remains one of the most important factors for the increased number of ART cycles in Japan. Thus, in 41.8% of registered cycles, women were in their 40s, similar to the previous year (41.9%), but decreased somewhat from 2015 (43.4%). This might be attributed to the encouragement offered to younger couples having infertility problem to enter ART programs; the Japanese government provides incentives for women under 40s to receive six subsidies for ART to reduce the economic burden, whereas women aged 40‐42 can only receive a subsidy for three attempts. There is currently an upper limit of 73 000 000 JPY per household for the subsidies, but this policy might be changed because of the recent stagnation of the Japanese total fertility rate (TFR). The latest TFR of Japan for 2019 was 1.36, 4 which had decreased from 1.42 in 2018. 5 Establishment of effective policies for reversing this low TFR is an urgent problem in Japan's society.

The number of registered ART cycles, both fresh and frozen ET, increased from 2017 to 2018, but the numbers of neonates born in fresh ET cycles have been decreasing since 2016, mostly attributed to the decreased numbers of fresh ET cycles and increased numbers of freeze‐all cycles in Japan. As a result, more than 47% of fresh cycles were freeze‐all in Japan in 2018. This strategy is beneficial for avoiding complications related to ovarian stimulation, such as ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), especially in high‐risk patients such as those with polycystic ovary syndrome or high ovarian reserve. 6 Supraphysiological hormonal environment in fresh ET cycles might affect endometrial receptivity and implantation rate. 7 However, clinical evidence on the effect of a freeze‐all strategy for women with regular menstrual cycles is conflicting. 8 , 9 , 10 A recently published meta‐analysis including 11 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with 5379 patients reported that freeze‐all and subsequent elective FET demonstrated that importantly, neither the live birth rate (relative risk, RR 1.03, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.91‐1.17) in the subgroup of normal responders nor the cumulative live birth rate in the entire population (RR 1.04, 95% CI, 0.97‐1.11) were significantly different between the two groups. 7 On the other hand, a more recent multicenter RCT investigating the effect of blastocyst‐stage ET after freeze‐all or fresh ET cycles among 825 ovulatory women from China demonstrated that a freeze‐all strategy with subsequent elective FET achieved a significantly higher live birth rate than did fresh blastocyst ET (RR 1.26, 95% CI, 1.14‐1.41). 8 The mean age of participants was 28.8 years both for the fresh and frozen ET groups, and the mean number of aspirated oocytes was 14. Thus, we should be cautious when extrapolating these results to the Japanese population. A recent multicenter RCT conducted in Europe investigated the effect of freeze‐all and fresh blastocyst ET strategies with a gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist used to trigger final oocyte maturation among 460 women with regular menstrual cycles (mean age of participants 32.4 years in the freeze‐all group and 32.3 years in fresh ET group) demonstrated that the ongoing pregnancy rate, live birth rate, and obstetric and neonatal complications did not differ between the two groups. The study concluded that their findings warrant caution in the indiscriminate application of a freeze‐all strategy when there is no apparent risk of OHSS. 10

The strength of the Japanese ART registry is its mandatory reporting system with a high compliance rate, in cooperation with the government subsidy system. Using this system, nearly all participating ART facilities (621 of 622 facilities) have registered cycle‐specific information, so selection bias caused by a lack of participation in the registration system is unlikely. Nevertheless, several limitations exist in the registry. First, it includes only cycle‐specific information, so it is very difficult to identify cycles in the same patient using the registry in its current format. Given recent Japanese ART practice, in which nearly half of all initiated cycles are freeze‐all, widely used indicators such as pregnancy and live birth rates per aspiration cycle will be affected markedly, which could mislead public opinion regarding the quality of treatment as ET was not performed in most included fresh ART cycles. 11 It has been suggested recently that the cumulative live birth rate per oocyte aspiration is more suitable when reporting the success rate of ART outcomes. 12 , 13 Because the Japanese ART registry has asked for frozen cycles to include identification numbers for fresh cycles since 2014, using the information the cumulative live birth rate per aspiration might be informative in the future for Japan as nearly half of all cycles are freeze‐all. Second, the Japanese ART registry includes unfertilized oocyte freezing cycles only for medically indicated cases, such as fertility preservation in cancer patients (Tables 2 and 5); the registry does not include cycles with non‐medical indications: so to speak, “social oocyte freezing.” Because no other registration system currently exists for oocyte freezing, there is no information available for such cycles. Third, the registry includes several patient background factors for each cycle such as body mass index, numbers of previous pregnancies and parity, but the high missed reporting rate for those variables makes it impossible to adjust for them to calculate the success rate for ART in Japan.

In conclusion, our analysis of the ART registry for 2018 demonstrated that the total number of ART cycles increased from the previous year. SET was performed at a rate of more than 82%, resulting in a 97% singleton live birth rate. Although an increasing trend for frozen ET and freeze‐all cycles is evident Japan, further investigation is required to evaluate the effect of the freeze‐all strategy and frozen ET on cumulative live births, particularly with respect to maternal and neonatal safety issues. These data represent the latest clinical practices of ART in Japan. Further improvements in the ART registration system in Japan are important.

DISCLOSURES

Conflict of interest: There is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this study. Human rights statement and informed consent: All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the relevant committees on human experimentation (institutional and national) and the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. Animal rights: This report does not contain any studies performed by any of the authors that included animal participants.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Not applicable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all of the registered facilities for their cooperation in providing their responses. We would also like to encourage these facilities to continue promoting use of the online registry system and assisting us with our research. We thank James Cummins, PhD, from Edanz Group (https://en‐author‐services.edanzgroup.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript. This study was supported by Health and Labor Sciences Research Grants.

Ishihara O, Jwa SC, Kuwahara A, et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Japan: A summary report for 2018 by the Ethics Committee of the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Reprod Med Biol.2021;20:3–12. 10.1002/rmb2.12358

REFERENCES

- 1. Adamson GD, et al.International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology: world report on assisted reproductive technology, 2016. 2020. https://secureservercdn.net/198.71.233.47/3nz.654.myftpupload.com/wp‐content/uploads/ICMART‐ESHRE‐WR2016‐FINAL‐20200901.pdf Accessed September 13, 2020.

- 2. Ishihara O, Jwa SC, Kuwahara A, et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Japan: a summary report for 2016 by the Ethics Committee of the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Reprod Med Biol. 2019;18:7‐16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Irahara M, et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Japan: a summary report of 1992–2014 by the Ethics Committee, Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Reprod Med Biol. 2017;16:126‐132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare . Summary of vital statistics in 2019 Tokyo. 2020. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/jinkou/kakutei19/dl/02_kek.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2020

- 5. Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare . Summary of vital statistics in 2018 Tokyo. 2019. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/jinkou/kakutei18/dl/02_kek.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2020

- 6. Chen ZJ, et al. Fresh versus frozen embryos for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:523‐533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Roque M, et al. Fresh versus elective frozen embryo transfer in IVF/ICSI cycles: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of reproductive outcomes. Hum Reprod Update. 2019;25:2‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wei D, et al. Frozen versus fresh single blastocyst transfer in ovulatory women: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;393:1310‐1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vuong LN, et al. IVF transfer of fresh or frozen embryos in women without polycystic ovaries. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:137‐147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stormlund S, et al. Freeze‐all versus fresh blastocyst transfer strategy during in vitro fertilisation in women with regular menstrual cycles: multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2020;370:m2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Adamson GD, et al. International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology: world report on assisted reproductive technology, 2011. Fertil Steril. 2018;110:1067‐1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maheshwari A, McLernon D, Bhattacharya S. Cumulative live birth rate: time for a consensus? Hum Reprod. 2015;30:2703‐2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Malizia BA, Hacker MR, Penzias AS. Cumulative live‐birth rates after in vitro fertilization. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:236‐243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]