Abstract

By employing a phenotypic screen, a set of compounds, exemplified by 1, were identified which potentiate the ability of histone deacetylase inhibitor vorinostat to reverse HIV latency. Proteome enrichment followed by quantitative mass spectrometric analysis employing a modified analogue of 1 as affinity bait identified farnesyl transferase (FTase) as the primary interacting protein in cell lysates. This ligand-FTase binding interaction was confirmed via X-ray crystallography and temperature dependent fluorescence studies, despite 1 lacking structural and binding similarity to known FTase inhibitors. Although multiple lines of evidence established the binding interaction, these ligands exhibited minimal inhibitory activity in a cell-free biochemical FTase inhibition assay. Subsequent modification of the biochemical assay by increasing anion concentration demonstrated FTase inhibitory activity in this novel class. We propose 1 binds together with the anion in the active site to inhibit farnesyl transferase. Implications for phenotypic screening deconvolution and HIV reactivation are discussed.

Keywords: HIV latency, phenotypic screen, HDAC inhibitor, farnesyltransferase inhibitor

Phenotypic screening is an important method for identifying tool compounds to elicit desired cellular responses in a mechanistically agnostic manner.1−3 It has been employed extensively in target and drug discovery including identification of novel mechanisms of action as well as in drug repurposing.4 We applied this approach to identify molecules capable of activating HIV transcription in latently infected cells. During its life cycle, HIV establishes a population of long-lived, latently infected resting memory T-cells that are transcriptionally quiescent, synthesize no viral proteins, and are undetected by the host immune response. These cells contain a full viral genome, but because the HIV provirus it encodes is transcriptionally silent, they are not impacted by direct acting antiviral drugs and remain invisible to the immune system. Activation of HIV transcription in this population of cells, termed HIV latency reversal, is thought to contribute to the rebound in HIV infection after antiretroviral therapy is discontinued. There has been intense interest in identifying agents that reverse HIV latency without nonspecifically activating T-cells, to “flush” or “shock” proviral HIV from these latent cells, artificially inducing viral antigen expression, thereby making them amenable to detection and, most importantly, treatment.5,6 The histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) panobinostat,7 romidepsin8 and vorinostat,9 have shown clinical promise in terms of flushing HIV from latent cells without T-cell activation.10,11 Although expression of viral protein was detected in a subset of these studies, both the magnitude of HIV mRNA expressed and the proportion of latently infected cell population affected was low.12 We and others have sought to identify HIV latency reversing agents via ultrahigh throughput phenotypic screening.13 Our strategy focused on identifying novel compounds and mechanisms which work in synergy with vorinostat, with the goal of improving the overall magnitude of latency reversal efficacy in vivo. While vorinostat can efficiently induce HIV transcription in in vitro model systems of HIV latency, the magnitude of HIV latency reversal that can be achieved at the maximal human vorinostat exposures in these systems is suboptimal. As higher doses of HDAC inhibitors (HDACi) in humans are limited by toxicity,14 we sought to identify compounds that could induce maximal HIV expression at lower HDACi concentration without a concomitant increase cytotoxicity. In our screen, multiple classes of compounds were identified and will be described in due course. This report focuses on the benzimidazole class exemplified by compound 1 (Figure 1). By employing biophysical, biochemical, and structural studies, compound 1 was determined to inhibit farnesyl transferase (FTase) via an anion codependent mechanism.

Figure 1.

Phenotypic screen used to identify compound 1. 2.9 million compounds were screened against a cell infected with latent HIV in the presence of an EC10 of known latency reactivation agent vorinostat with the goal of finding new molecules which could act in synergy with vorinostat. Hits from this screen which reverse HIV latency result in the expression of luciferase reporter protein (illustrated with stars).

Results

HDACi Synergy Screen and Identification of HIV Latency Reversal Agent Compound 1

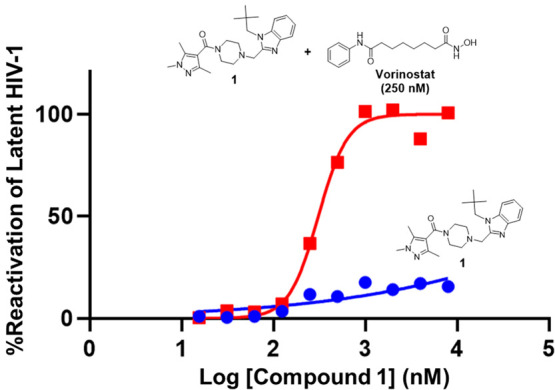

We sought to identify novel latency reactivation agents (LRAs) via a phenotypic screen. The screen was designed to detect compounds which synergize with, or add to the activity of the known HIV LRA vorinostat, a nonselective HDAC inhibitor. Briefly, an automated screen of 2.9 million compounds was performed using a Jurkat T-cell line harboring a latent HIV reporter (2C4 cells). These cells were treated with nonsaturating levels of vorinostat (250 nM), which corresponds to an EC10 in Jurkat 2C4 cells. The Jurkat 2C4 cell line contains a quiescent minimal HIV proviral genome containing HIV Env, Rev, an attenuated form of Tat (H12L) and a luciferase reporter gene under transcriptional control of the HIV LTR. Under basal conditions, HIV transcription is restricted by chromatin modifications and no significant reporter gene activity is detected. In the presence of LRAs, like HDAC inhibitors, HIV latency reversal is read out as an increase in luciferase reporter luminescence in cell lysates. The primary screen of 2.9 million compounds (tested at 4 μM) identified 16 200 compounds that showed greater than 10–20% of the maximal vorinostat stimulation activity in the assay. For this report, we wish to focus on one chemotype, exemplified by compound 1, which exhibited the desired phenotype (Figure 2). In the presence of vorinostat (EC10), 1 showed 100% stimulation activity, while in the absence of vorinostat, exhibited minimal stimulatory activity (Figure 3). Examination of structural analogues in the screen showed varying degrees of activity as well. As an extreme example, compound 2 did not exhibit activity in this assay highlighting the importance of substitution on the benzimidazole (Figure 2). Given the attractive cellular activity of 1, we sought to understand the mechanism by which it served to potentiate the activity of vorinostat by identifying its protein binding partner(s).

Figure 2.

Compound 1 was identified in a phenotypic screen. Compounds 2–4 were used to elucidate mechanism of action. For the EC50’s reported, 100% stimulatory activity was observed; 100% activity defined as max activity observed with vorinostat; EC10 vorinostat = 250 nM.

Figure 3.

Representative example of latent HIV activation by 1 (blue circles) and [1 + vorinostat] (red squares) in Jurkat 2C4 cells.

Mechanism of Action Assessment for 1

Profiling 1 for binding affinity and functional biochemical activity against common protein family panels (e.g., kinase, epigenetic regulators, GPCRs, ion channels) did not yield hits and offered little insight into mechanism. Similarly, in silico chemo-genomic profiling against our internal database of compound–protein interactions resulted in no clear association of this chemotype to a particular protein.15 Given the lack of traction with such profiling techniques, we chose to interrogate the mechanism of action via chemoproteomics.16 To facilitate this, compound 1 was modified with an ethyl amino linker on the nitrogen pyrazole (3; Figure 2) to permit immobilization via amidation on cross-linked agarose beads. Gratifyingly, model compound 4, with the linker capped N-acetamide meant to mimic resin immobilization, exhibited activity in the HDAC Jurkat synergy assay with an EC50 only slightly higher than 1, suggesting that the affinity matrix conjugate derived from 3 would maintain binding in the pull-down experiment. Cellular target profiling described herein with these compounds was performed at Evotec. Compound 3 was thus immobilized on Sepharose beads at three different concentrations (5.8, 3, and 1.4 mM) and exposed to the Jurkat cell lysates which had previously been treated with vorinostat (250 nM) to explore optimal affinity matrix/lysate ratio. Beads were washed and eluted, and bound proteins were digested, analyzed by LC-MS/MS, and detected ions matched to known tryptic peptides. Compound 3 specifically enriched proteins from cell lysate, and competition of a subset of bound proteins with 1 (30 μM) was used to differentiate specific versus nonspecific binders. At the lowest coupling density, only four proteins behaved consistently as potential targets, i.e., showing consistent enrichment across two displacement experiments: farnesyltransferase/geranylgeranyltransferase type-1 subunit alpha (FNTA), protein farnesyltransferase subunit beta (FNTB), NmrA-like family domain-containing protein 1 (NMRAL1), and AFG3-like protein 2 (AFG3L2). The parent benzimidazole 1 was used to compete with the affinity matrix allowing for binding determination. The Kd values for farnesyltransferase subunit alpha and beta with 1 were measured to be 340 and 475 nM, respectively. The NMRAL1 Kd was ∼19 μM and that of AFG3L2 was approximated at 19 μM as no displacement below 50% was observed. Given that farnesyl transferase exists as a dimer of alpha and beta domains, the Kd values were likely those measured against the dimer itself. Furthermore, 2 did not displace 1 in these experiments providing additional confidence that FTase was likely the biological target of interest. We thus focused follow up work on further elucidating this potential interaction with farnesyltransferase (FTase).

Farnesyltransferase (FTase) catalyzes the reaction of farnesylpyrophosphate (FPP) with a cysteine on a polypeptide to give a farnesyl thioether (Figure 4).17,18 As such, our first experiment was to test the ability of 1 to inhibit this process. Despite evidence for binding, no activity was observed when employing reported conditions used for known FTase inhibitors.19 It should be noted that 1 and analogues do not exhibit structural similarity to known FT inhibitor classes. In order to increase confidence in the hypothesis that 1 binds FTase we sought additional evidence for binding leveraging biophysical and structural methods.

Figure 4.

Farnesyltransferase mediated farnesyl addition to a cysteine of the Ras protein.17

The interaction of compound 1 with purified recombinant FTase was probed by employing temperature dependent fluorescence (TdF),20 which monitors the ligand-induced conformational stabilization of a protein. Thermal stabilization of FTase was assessed by comparing melting temperature (Tm) in the absence and presence of a saturating concentration of 1 (20 μM, >100x Kd from pull-down experiments). We observed a significant increase in the melting temperature of FTase in the presence of 1 (Tm = 50.4 ± 0.3 °C) compared to FTase in the absence of 1 (Tm = 46.2 ± 0.2 °C). This large shift in melting temperature (ΔTm = 4.2 °C) is indicative of a significant structural stabilization of FTase providing orthogonal evidence of binding of 1. Consistent with the cellular data, compound 2 exhibited only weak activity in the TdF experiment (ΔTm = 2 °C). While 1 did not exhibit biochemical activity, the TdF experiment increased confidence that it did in fact interact with FTase.

Given the results observed with TdF, we sought to further elucidate the interaction between compound 1 and FTase by pursuing an X-ray cocrystal structure. In a manner described previously with known FTase inhibitors, compound 1 and farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP; Figure 5) were soaked in crystals of FTase produced with bound α-hydroxy farnesyl phosphonic acid (HFP).21 No density for compound 1 was observed but clear density was observed for FPP which displaced HFP. As a follow-up screen, the original soaking experiment was repeated but instead of FPP, the truncated pyrophosphates dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMA-PP) and pyrophosphate (PPV) were individually examined with 1. Gratifyingly, density for 1 was clearly visible for both soaks (Figure 6). The density of PPV was very weak but enough to build an image. The structures of 1 in complex with FTase and DMA-PP (Figure 6a) and PPV are nearly superimposable (Figure 6b) suggesting that the binding mode of 1 does not change in the presence of the different anions. Two hydrogen bonds are observed between 1 and the side chains of chain B Ser99 and Arg202 while enclosed by a very hydrophobic environment. A closer examination reveals that 1 makes contacts across both the F-PP and CaaX pockets (Figure 7a). These pockets, along with the catalytic zinc atom, define the FTase active site, as the enzyme catalyzes transfer of the farnesyl group to the cysteine of the substrate CaaX motif. The binding mode for 1 is analogous to that observed for Lonafarnib (PDB 1O5M).22 The neopentyl group in 1 sits in a hydrophobic pocket. The ethyl moiety in 2 is insufficient to leverage these interactions potentially providing rationale for why 2 does not bind. Taken together, the chemoproteomic pulldown experiment, TdF data, and X-ray crystal structures demonstrate unambiguously that 1 binds to FTase.

Figure 5.

Anions used in cocrystallization studies with farnesyl transferase and compound 1.

Figure 6.

(a) X-ray crystal structure of FTase/DMA-PP/compound 1 complex. (b) X-ray crystal structure of FTase/PPV/compound 1 complex overlaid with structure of FTase/DMA-PP/compound 1.

Figure 7.

(a) Overlay of farnesyltransferase structures of compound 1 (this work), F-PP (from PDB1O5M), and the CaaX peptide Cys-Val-Iso-Met (from PDB 1QBQ). (b) Schematic highlighting role of t-butyl and piperidine moieties in this interaction.

Confident that 1 interacts with purified FTase in the active site, we revisited assessment of FTase inhibition activity. In particular, we sought to understand why compound 1 did not exhibit activity in the farnesyl transferase biochemical assay. The X-ray structure demonstrates that 1 likely disrupts the F-PP and CaaX binding interfaces. Furthermore, the observation that PPV or DMA-PP were necessary for detection of bound 1 in the X-ray structure analysis provides evidence that the anion may be required for inhibitory activity as well. The FTase inhibition assay was thus repeated in the presence of increasing concentrations of added dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMA-PP, Figure 8). Compound 5, a well-characterized FTase inhibitor which progressed to clinical studies (L-778,123), was employed as a positive control.17,23 As observed in Figure 7, DMA-PP has a marked effect on FTase activity, increasing inhibition 1 by orders of magnitude, to the point of equivalence with its observed cellular activity Jurkat latency reversal assay (0.34 μM versus ∼1 μM, Figure 2). Importantly, DMA-PP has minimal impact on FTi activity of control compound 5. It has been reported that nonorganic anions can have an impact on FTi activity,24 so we expanded the scope of our studies beyond DMA-PP. Analogous to the experiments with DMA-PP, inorganic anions also had an impact on FTi activity of compound 1 but not compound 2 or 5 (Figure 9). It is noted that compound 5 also has activity in the latency reversal assay (EC50 = 170 nM, 100% activation with 250 nM vorinostat present; minimal activity without vorinostat). Taken together, the results above suggest that the mechanism of HIV latency reversal by 1 in the presence of vorinostat is through farnesyl transferase inhibition. Lastly, given the implications of farnesyltransferase inhibition as a means of HIV activation in the presence of vorinostat, we also examined known farnesyltransferase inhibitors and demonstrated a strong correlation between farnesyltransferase inhibitory activity and cellular activity in the presence of vorinostat (Supporting Information).

Figure 8.

Impact of dimethylallylphosphate (DMA-PP) on farnesyl transferase inhibition by compound 1 and compound 5 (known FTase inhibitor). Note that anion alone does not inhibit FTase activity.

Figure 9.

Impact of 5 mM salt on enzymatic farnesyltransferase activity in the presence of 1, 2, and 5. Note that anion alone does not inhibit FTase activity.

Discussion

Reversal of HIV latency is a critical component of the “flush and kill” strategy for eradicating virus from infected patients.25 Inhibitors of histone deacetylase have been shown to flush latent virus clinically, as detected by increases in both viral mRNA as well as viral protein (p24). Despite this success, the magnitude of HIV mRNA expression observed is low and raises the question whether the magnitude of the response could be insufficient to induce significant HIV antigen expression. Thus, new mechanisms and molecules which potentiate or synergize with HDACi are of great interest. We conducted a phenotypic screen for novel chemical matter to augment HDACi activity. Compound 1, which exhibits LRA activity only in the presence of an HDACi, is representative of one class of molecules which came from this screen. Because its activity is dependent on cotreatment with an HDACi, it behaves differently from other HDACi suggesting an alternate mechanism of action. Given its desirable activity and the need to understand underlying mechanisms of HIV latency reversal, we sought to elucidate the mechanism of action of 1.

Compound 1 was profiled using a variety of experimental and computational approaches, but no target associations were compelling for further study. This prompted leveraging structure–activity relationships from closely related analogues identified in the phenotypic screen to build probe molecule 3 which was subsequently used in a chemo-proteomic pull-down experiment which identified FTase as a likely binding partner of this class of molecules. FTase was prioritized for further study because of the specificity of the affinity enrichment (competed by free 1), the quantitative alignment of chemoproteomic apparent Kd and cellular potency (0.34 versus 1.0 uM), the pull-down of both FTase subunits, and the high selectivity (low number of binding proteins detected) of the pull-down. An X-ray cocrystal structure and biophysical data unambiguously demonstrate FTase binding. Lastly, inhibition of purified FTase by 1 was demonstrated in a biochemical assay (i.e., cell-free), but was observed only in the presence of added anion beyond what is prescribed in a standard protocol.19

The requirement of elevated anion concentration for observation of compound 1 FTase inhibition activity is postulated to result from the binding interactions of 1 in the active site. In contrast to the majority of FTase inhibitors which bind in either the FPP or CaaX pocket, 1 partially occupies both pockets in an unusual bridged binding mode (Figure 7a).18 The degree of overlap in either pocket is likely insufficient to independently inhibit FTase mediated catalysis. Small anions, based on these data, can act in concert with 1, i.e., anion blocking the pyrophosphate site and 1 binding the CaaX and farnesyl sites (Figure 7b). Independently, anion and 1 by themselves are insufficient to prevent FTase catalysis. This observation has been made previously with structurally distinct FTase inhibitors.24,26,27 Based on a small screen (Figure 9), it appears that polyvalent anions are necessary for inhibition—likely serving as a surrogate for the diphosphate in FPP. In the cell-based HIV latency assays as well as cell lysates used for pull-downs, either ATP, pyrophosphate or phosphate is likely present in sufficient concentrations to enhance the activity of 1 for the FTase active site, in contrast to those used in the biochemical conditions.

The prerequisite for additional anion to be present also has implications for phenotypic screening and mechanism deconvolution. After a phenotypic screen is performed, one can typically be presented with numerous hits of interest. Elucidating mechanism of action of these hits requires substantial investment and typically relies upon multiple lines of investigation, including leveraging literature assay protocols for proteins. While perfectly sound, these assay conditions are not necessarily general and may result in false negatives, as observed here for 1 and FTase. It was only with complementary mechanistic tools (X-ray, Tdf, pull-down), that we were able to elucidate the mechanism of action. In this context, it is important to reiterate the frequent refrain that biochemical conditions do not necessarily mimic cellular conditions.

Lastly, FTase and 1 itself serve as useful entry points into new mechanisms for HIV latency. FTase plays an important role in farnesylation of signaling proteins.17 Interestingly, 1 cannot reverse HIV latency alone. It is postulated that vorinostat is first required to change or relax the chromatin environment sufficiently to allow transcription to occur.28 Given the critical role FTase plays in farnesylation of signaling proteins, there is potentially a downstream protein that regulates latency reversal, but requires farnesylation to occur first. Prevention of farnesylation of this speculative protein(s), via inhibition of FTase with molecules like 1, potentially augments reactivation of latent HIV after vorinostat serves to “turn the system on”. Additional mechanistic work on FTase and HDAc inhibition as it relates to HIV and further output from the phenotypic screen will be reported separately.

Conclusion

We have identified a new class of FTase inhibitors, exemplified by 1, which can activate latent HIV in the presence of vorinostat. Based on X-ray and biochemical data, inhibition of FTase by 1 occurs in a cooperative sense with polyvalent anion. This mechanism underscores the challenge and importance of understanding cellular conditions in establishing biochemical assays. Lastly, identification of new chemical matter via addition of an anion suggests the potential for finding unique, relevant chemical matter against different targets by simple modification of assay conditions.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- FTase

farnesyltransferase

- FTi

farnesyltransferase inhibitor

- HDACi

histone deacetylase inhibitors

- LRA

latency reactivation agent

- LTR

long terminal repeat

- FNTA

farnesyltransferase subunit alpha

- FNTB

farnesyltransferase subunit beta

- FPP

farnesylpyrophosphate

- TdF

Temperature dependent Fluorescence

- ΔTm

shift in melting temperature

- HFP

α-hydroxy farnesyl phosphonic acid

- DMA-PP

dimethylallyl diphosphate

- PPV

pyrophosphate

- CaaX

generic cysteine containing polypeptide

- Cys

cysteine

- Val

valine

- Iso

isoleucine

- Met

methionine

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00551.

Phenotypic screen details; synthetic procedures; temperature dependent fluorescence experimental and first derivative of fluorescence data; biochemical assay experiments; X-ray structure information and Moe ligand interaction information; FTase biochemical inhibition vs vorinostat cellular activity in the presence of FTi’s (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Swinney D. C.; Anthony J. How were new medicines discovered?. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2011, 10, 507–519. 10.1038/nrd3480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee O. W.; Austin S.; Gamma M.; Cheff D. M.; Lee T. D.; Wilson K. M.; Johnson J.; Travers J.; Braisted J. C.; Guha R.; Klumpp-Thomas C.; Shen M.; Hall M. D. Cytotoxic Profiling of Annotated and Diverse Chemical Libraries Using Quantitative High-Throughput Screening. SLAS Discov 2020, 25, 9–20. 10.1177/2472555219873068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childers W. E.; Elokely K. M.; Abou-Gharbia M. The Resurrection of Phenotypic Drug Discovery. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 1820–1828. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinney D. C. Phenotypic vs. target-based drug discovery for first-in-class medicines. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 93, 299–301. 10.1038/clpt.2012.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen T. A.; Lewin S. R. Shocking HIV out of hiding: where are we with clinical trials of latency reversing agents?. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2016, 11, 394–401. 10.1097/COH.0000000000000279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemming A. Shocking HIV out of hiding. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 138–139. 10.1038/s41577-020-0283-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen T. A.; Tolstrup M.; Brinkmann C. R.; Olesen R.; Erikstrup C.; Solomon A.; Winckelmann A.; Palmer S.; Dinarello C.; Buzon M.; Lichterfeld M.; Lewin S. R.; Østergaard L.; Søgaard O. S. Panobinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, for latent-virus reactivation in HIV-infected patients on suppressive antiretroviral therapy: a phase 1/2, single group, clinical trial. lancet. HIV 2014, 1, e13–e21. 10.1016/S2352-3018(14)70014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Søgaard O. S.; Graversen M. E.; Leth S.; Olesen R.; Brinkmann C. R.; Nissen S. K.; Kjaer A. S.; Schleimann M. H.; Denton P. W.; Hey-Cunningham W. J.; Koelsch K. K.; Pantaleo G.; Krogsgaard K.; Sommerfelt M.; Fromentin R.; Chomont N.; Rasmussen T. A.; Østergaard L.; Tolstrup M. The Depsipeptide Romidepsin Reverses HIV-1 Latency In Vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1005142 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks P. A.; Breslow R. Dimethyl sulfoxide to vorinostat: development of this histone deacetylase inhibitor as an anticancer drug. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 84–90. 10.1038/nbt1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archin N. M.; Liberty A. L.; Kashuba A. D.; Choudhary S. K.; Kuruc J. D.; Crooks A. M.; Parker D. C.; Anderson E. M.; Kearney M. F.; Strain M. C.; Richman D. D.; Hudgens M. G.; Bosch R. J.; Coffin J. M.; Eron J. J.; Hazuda D. J.; Margolis D. M. Administration of vorinostat disrupts HIV-1 latency in patients on antiretroviral therapy. Nature 2012, 487, 482–485. 10.1038/nature11286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott J. H.; Velayudham P.; Wightman F.; Solomon A.; Smith M. Z.; Cameron P. U.; Lewin S. R.; Ghneim K.; Ahlers J.; Cameron M. J.; Chomont N.; Fromentin R.; Procopio F. A.; Zeidan J.; Sekaly R.-P.; Spelman T.; McMahon J.; Brown G.; Roney J.; Hoy J. F.; Watson J.; Prince M. H.; Johnstone R. W.; Martin B. P.; Palmer S.; Odevall L.; Sinclair E.; Deeks S. G.; Hazuda D. J. Activation of HIV transcription with short-course vorinostat in HIV-infected patients on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004473 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G.; Swanson M.; Talla A.; Graham D.; Strizki J.; Gorman D.; Barnard R. J.; Blair W.; Søgaard O. S.; Tolstrup M.; Østergaard L.; Rasmussen T. A.; Sekaly R.-P.; Archin N. M.; Margolis D. M.; Hazuda D. J.; Howell B. J. HDAC inhibition induces HIV-1 protein and enables immune-based clearance following latency reversal. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e92901 10.1172/jci.insight.92901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolkenberg S. E.; Tellers D. M.; Converso A.; Barnard R. J. O. Approaches to eradicate HIV infection. Med. Chem. Rev. 2016, 51, 207–225. 10.29200/acsmedchemrev-v51.ch13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suraweera A.; O’Byrne K. J.; Richard D. J. Combination Therapy With Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors (HDACi) for the Treatment of Cancer: Achieving the Full Therapeutic Potential of HDACi. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 92–92. 10.3389/fonc.2018.00092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutchukian P. S.; Chang C.; Fox S. J.; Cook E.; Barnard R.; Tellers D.; Wang H.; Pertusi D.; Glick M.; Sheridan R. P.; Wallace I. M.; Wassermann A. M. CHEMGENIE: integration of chemogenomics data for applications in chemical biology. Drug Discovery Today 2018, 23, 151–160. 10.1016/j.drudis.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K.; Weber C.; Bairlein M.; Greff Z.; Kéri G.; Cox J.; Olsen J. V.; Daub H. Proteomics strategy for quantitative protein interaction profiling in cell extracts. Nat. Methods 2009, 6, 741–744. 10.1038/nmeth.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell I. M. Inhibitors of Farnesyltransferase: A Rational Approach to Cancer Chemotherapy?. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 1869–1878. 10.1021/jm0305467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long S. B.; Casey P. J.; Beese L. S. Reaction path of protein farnesyltransferase at atomic resolution. Nature (London, U. K.) 2002, 419, 645–650. 10.1038/nature00986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F. L.; Bishop W. R. Protein Farnesyltransferase Assays. Curr.Protoc. Pharmacol. 1998, 00, 3.4.1–3.4.13. 10.1002/0471141755.ph0304s00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantoliano M. W.; Petrella E. C.; Kwasnoski J. D.; Lobanov V. S.; Myslik J.; Graf E.; Carver T.; Asel E.; Springer B. A.; Lane P.; Salemme F. R. High-Density Miniaturized Thermal Shift Assays as a General Strategy for Drug Discovery. J. Biomol. Screening 2001, 6, 429–440. 10.1177/108705710100600609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z.; Demma M.; Strickland C. L.; Syto R.; Le H. V.; Windsor W. T.; Weber P. C. High-level expression, purification, kinetic characterization and crystallization of protein farnesyltransferase β-subunit C-terminal mutants. Protein Eng., Des. Sel. 1999, 12, 341–348. 10.1093/protein/12.4.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland C. L.; Weber P. C.; Windsor W. T.; Wu Z.; Le H. V.; Albanese M. M.; Alvarez C. S.; Cesarz D.; del Rosario J.; Deskus J.; Mallams A. K.; Njoroge F. G.; Piwinski J. J.; Remiszewski S.; Rossman R. R.; Taveras A. G.; Vibulbhan B.; Doll R. J.; Girijavallabhan V. M.; Ganguly A. K. Tricyclic Farnesyl Protein Transferase Inhibitors: Crystallographic and Calorimetric Studies of Structure-Activity Relationships. J. Med. Chem. 1999, 42, 2125–2135. 10.1021/jm990030g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appels N. M. G. M.; Beijnen J. H.; Schellens J. H. M. Development of Farnesyl Transferase Inhibitors: A Review. Oncologist 2005, 10, 565–578. 10.1634/theoncologist.10-8-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholten J. D.; Zimmerman K. K.; Oxender M. G.; Leonard D.; Sebolt-Leopold J.; Gowan R.; Hupe D. J. Synergy between anions and farnesyldiphosphate competitive inhibitors of farnesyl:protein transferase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 18077–18081. 10.1074/jbc.272.29.18077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzig E.; Kim K. C.; Packard T. A.; Vardi N.; Schwarzer R.; Gramatica A.; Deeks S. G.; Williams S. R.; Landgraf K.; Killeen N.; Martin D. W.; Weinberger L. S.; Greene W. C. Attacking Latent HIV with convertibleCAR-T Cells, a Highly Adaptable Killing Platform. Cell (Cambridge, MA, U. S.) 2019, 179, 880–894. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotter B. W.; Quigley A. G.; Lumma W. C.; Sisko J. T.; Walsh E. S.; Hamann C. S.; Robinson R. G.; Bhimnathwala H.; Kolodin D. G.; Zheng W.; Buser C. A.; Huber H. E.; Lobell R. B.; Kohl N. E.; Williams T. M.; Graham S. L.; Dinsmore C. J. 2-Arylindole-3-acetamides FPP-Competitive inhibitors of farnesyl protein transferase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001, 11, 865–869. 10.1016/S0960-894X(01)00061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid T. S.; Long S. B.; Beese L. S. Crystallographic Analysis Reveals that Anticancer Clinical Candidate L-778,123 Inhibits Protein Farnesyltransferase and Geranylgeranyltransferase-I by Different Binding Modes. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 9000–9008. 10.1021/bi049280b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W. S.; Parmigiani R. B.; Marks P. A. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: molecular mechanisms of action. Oncogene 2007, 26, 5541–5552. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.