Abstract

Background:

Sleep is thought to be important for behavioral and cognitive development. However, much of the prior research on sleep’s role in behavioral/cognitive development has relied upon self-report measures and cross-sectional designs.

Methods:

The current study examined how early childhood sleep, measured actigraphically, was developmentally associated with child functioning at 54 months. Emphasis was on functioning at preschool, a crucial setting for the emergence of psychopathology. Participants included 119 children assessed longitudinally at 30, 36, 42, and 54 months. We examined correlations between child sleep and adjustment across three domains: behavioral adjustment (i.e., internalizing and externalizing problems), socioemotional skills, and academic/cognitive abilities. We further probed consistent associations with growth curve modeling.

Results:

Internalizing problems were associated with sleep variability, and cognitive and academic abilities were associated with sleep timing. Growth curve analysis suggested that children with more variable sleep at 30 months had higher teacher-reported internalizing problems in preschool and that children with later sleep timing at 30 months had poorer cognitive and academic skills at 54 months. However, changes in sleep from 30 to 54 months were not associated with any of the domains of adjustment.

Conclusions:

Findings indicate that objectively measured sleep variability and late sleep timing in toddlerhood are associated with higher levels of internalizing problems and poorer academic/cognitive abilities in preschool.

Keywords: Sleep, adjustment problems

Introduction

Nearly 25% of children experience some type of sleep problem (Owens, 2007). For some children, this includes clinical sleep problems, such as dyssomnias (e.g., trouble falling asleep or frequent night wakings), parasomnias (e.g., sleepwalking, night terrors), sleep disordered breathing, and behavioral sleep problems (e.g., child bedtime resistance, nighttime fears). For more children, this includes variations in basic sleep parameters (e.g., short total sleep durations, lack of sleep consolidation) that appear to affect child functioning. A meta-analysis by Astill, Van der Heijden, Van IJzendoorn, and Van Someren (2012) demonstrated a link between short sleep duration and adjustment problems in 5- to 12-year-old children, including elevated externalizing and internalizing problems, and poorer executive functioning, higher-order cognitive abilities, and school performance. However, there has been much less research on how sleep problems relate to similar cognitive and behavioral skills in early childhood. Cognitive and regulatory skills develop rapidly in early childhood, so sleep loss may be especially consequential during this time (Beebe, 2011). To advance understanding of the role of sleep in children’s adaptive functioning in early childhood, the current study examined how sleep measured across two years of development in early childhood, from 30 months to 54 months, was associated with child functioning at 54 months in preschool, a crucial setting for the emergence of psychopathology versus competent adjustment.

Sleep and behavioral adjustment

Considerable research has focused on the association between poor sleep, broadly defined, and both internalizing and externalizing psychopathology (Gregory & Sadeh, 2012). Associations have been reported between parent-reported sleep problems in early childhood and increased externalizing problems, such as aggression, inattention, hyperactivity, and conduct problems (Goodlin-Jones, Tang, Liu, & Anders, 2009; Goodlin-Jones, Waters, & Anders, 2009; Hiscock, Canterford, Ukoumunne, & Wake, 2007; Lavigne et al., 1999; Quach, Nguyen, Williams, & Sciberras, 2018; Scharf, Demmer, Silver, & Stein, 2013; Staples & Bates, 2011), increased internalizing problems, such as depression, withdrawal, and anxiety (Goodlin-Jones, Tang, et al., 2009; Hiscock et al., 2007), and poorer adjustment overall (both positive and negative classroom behaviors as rated by preschool teachers; Bates, Viken, Alexander, Beyers, & Stockton, 2002). Longitudinal research suggests that increased parent-reported sleep problems in early childhood are associated with behavioral and emotional problems in early to mid-adolescence, even when controlling for previous levels of behavioral and emotional problems (Gregory & O’Connor, 2002; Quach et al., 2018).

Findings from research focused on the association between early childhood sleep (measured with actigraphy) and behavioral adjustment (i.e., internalizing and externalizing problems) have been less consistent. Cremone et al. (2018) found that later sleep timing moderated the association between negative affect and both internalizing and externalizing problems in young children, such that children high on negative affect showed the most externalizing and internalizing problems when they also had later sleep timing, but main effects between sleep and overall externalizing/internalizing problems were not found (Cremone et al., 2018). Similarly, Goodlin-Jones, Waters, et al. (2009) found no difference in actigraphic sleep parameters between preschoolers with and without clinically elevated attention problems. So, while there is substantial evidence for an association between parent reports of sleep problems and psychopathology in early childhood, additional research is needed to determine if this extends to objectively measured sleep.

Sleep and socioemotional skills

In the preschool period, where there is often a transition to formal education settings, socioemotional competencies increase in salience. Relatively few studies have focused on the association between sleep and socioemotional skills, but shorter sleep durations are reported to be associated with poorer socioemotional skills in early childhood. Vaughn, Elmore-Staton, Shin, and El-Sheikh (2015) found an association between actigraphically measured sleep duration and peer social competence. Preschoolers with longer sleep durations were better-liked by their peers and engaged more effectively in the classroom (Vaughn et al., 2015). Williams, Nicholson, Walker, and Berthelsen (2016) demonstrated that children with non-normative sleep patterns from birth to age 5 (i.e., poor sleep and increasing sleep problems with age; groups determined using latent profile analysis) were rated by teachers (at ages 6 – 7) as having poorer emotional skills and fewer prosocial skills in the classroom. Similarly, Tso et al. (2016) found that preschoolers with shorter sleep durations (i.e., eight or fewer hours of sleep per night) had poorer teacher-reported social competence and emotional maturity than their peers with longer sleep durations. Though not in the context of the classroom, Williams, Berthelsen, Walker, and Nicholson (2015) demonstrated that parent-reported sleep problems, measured every two years from birth to age 7, were associated with poorer concurrent, parent-reported emotion regulation abilities. Additionally, Williams et al. (2015) further demonstrated that sleep problems in infancy and from ages 2 to 3 were associated with poorer emotion regulation skills two years later, even when controlling for prior levels of emotion regulation. These findings are encouraging, but further research is needed on the multiple aspects of socioemotional competence and their developmental relations with multiple aspects of sleep.

Sleep and academic/cognitive abilities

Sleep problems may affect academic/cognitive abilities through several interrelated mechanisms, including through increasing daytime sleepiness (Short & Banks, 2014), through decreasing neural synaptic pruning activity that facilitates learning and memory processes (Tononi & Cirelli, 2014), and through altering functioning in the prefrontal cortex (Jones & Harrison, 2001). Consistent with this, poor sleep has been associated with a range of academic/cognitive abilities in early childhood. Parent-reported sleep problems in preschoolers have been associated with teacher-reported learning problems (Quach, Hiscock, Canterford, & Wake, 2009) and poorer executive control (i.e., working memory and interference inhibition; Nelson, Nelson, Kidwell, James, & Espy, 2015). Shorter sleep durations in preschoolers have been associated with poorer receptive vocabulary (Vaughn et al., 2015) and poorer cognitive development (Tso et al., 2016). Greater nighttime sleep consolidation has been linked to better concurrent neurocognitive performance in preschoolers (Lam, Mahone, Mason, & Scharf, 2011) and improved executive functioning at age 4 (Bernier, Beauchamp, Bouvette Turcot, Carlson, & Carrier, 2013; sleep consolidation as measured in infancy). Jung, Molfese, Beswick, Jacobi-Vessels, and Molnar (2009) found that longer parent-reported sleep durations were associated with improved cognitive abilities at age 3, but were not significantly associated with changes in cognitive abilities from ages 3 to 8. Our previous work found that later timing of sleep, measured using actigraphs, was associated with poorer cognitive abilities in toddlerhood; however, within-subject changes in sleep timing were not associated with within-subject changes in cognitive abilities (Hoyniak et al., 2018).

Current study

The literature on sleep and preschool adjustment has several important limitations. First, much of this literature relies on parent reports of sleep. Although all methods for measuring child sleep are likely prone to error, there are a number of drawbacks to relying solely on parent reports of sleep, as parents may overestimate child sleep durations and are often unaware of how frequently and how long children awaken at night (Dayyat, Spruyt, Molfese, & Gozal, 2011; Tikotzky & Sadeh, 2001). The use of actigraphy data, which derives estimates of sleep and wake patterns based on motor activity recorded by an accelerometer, has shown high levels of correspondence with polysomnography (considered the ‘gold standard’ of sleep measurement) in individuals without sleep disorders (Kushida et al., 2001). However, actigraphs may be prone to overestimating night awakenings in children; as such, it is often recommended that researchers combine actigraphy data with sleep diaries (Dayyat et al., 2011; Kushida et al., 2001). Another limitation is that many studies focusing on sleep and adjustment in early childhood rely on parent reports of both sleep and adjustment, with findings potentially inflated due to shared method variance. Next, research has often focused on single indexes of sleep (e.g., only sleep duration or sleep efficiency), yet it is important to parse out which aspects of sleep, such as variability or lateness of bedtimes, are associated with adjustment outcomes. Finally, few studies examining the association between actigraphically measured sleep and adjustment in early childhood have been longitudinal, so developmental processes underlying this association have not been well explored. There is evidence to suggest both developmental change as well as stability in sleep parameters across childhood (Galland, Taylor, Elder, & Herbison, 2012; Gregory & O’Connor, 2002; Kuula et al., 2018; Quach et al., 2018), and research is needed to understand how these developmental changes are associated with adjustment outcomes.

The current study seeks to address these limitations in the literature, examining the longitudinal association between sleep, from toddlerhood to preschool, and several domains of adjustment (behavioral, socioemotional, cognitive, and academic). Sleep was measured longitudinally at four ages: 30, 36, 42, and 54 months, in association with measures of multiple domains of adjustment at 54 months. We expected that children who had shorter sleep durations, later sleep schedules, more night-to-night variability in sleep timing and duration, and more activity during sleep (i.e., more night awakenings) throughout early childhood would also show poorer adjustment outcomes during preschool. To fully utilize our longitudinal sleep data, we used latent growth curve analysis estimating latent intercept and slope factors to characterize the trajectory of change of the sleep indexes across this developmental window, and examining if individual differences in these growth parameters were associated with individual differences in preschool adjustment. Although we expected that higher levels of sleep problems would be associated with poorer adjustment in preschool, we were uncertain whether the association between sleep and adjustment would be due to children’s initial levels of sleep variables, or due to patterns of change in sleep across time. We expected that multiple domains of sleep problems (e.g., short sleep durations and variable sleep schedules) could be associated with adjustment outcomes, so we considered a comprehensive selection of sleep indexes. The current study includes a sample of children overlapping partly with that of Hoyniak et al. (2018), which focused only on sleep and cognitive abilities in toddlerhood, not the multiple domains of functioning and longer span of development of the present study.

Method

Participants

Participants included 119 children (59 female) recruited at 30 months of age and reassessed at 36, 42, and 54 months of age. Participants were recruited as part of a wider, multi-site longitudinal study, but only children at one site completed the 54-month assessment and were included in the current study. Children were eligible to be included if they attended some form of preschool for at least a portion of the week. On average, children attended preschool for 26 hours per week (SD = 12.67).

The sample was predominately White, non-Latinx (89%; 5% Latinx, 1% Black, 1% Mixed Race, 4% Other), from two-parent households (92%, 5% single parent, 3% other), with a college-educated primary caregiver (86% college degree, 9% some college, 5% high school diploma or less). Family socioeconomic status (SES), calculated using the Hollingshead Four Factor Index (Hollingshead, 1975), ranged from 13 to 66, with M = 51.33 (SD = 11.91), reflecting the predominantly middleclass characteristics of the sample.

Missingness for each variable included in analysis is described in Table S1. Missingness was primarily limited to sleep and academic abilities variables (per cent missing ranging from 15 to 22). Missingness for the actigraphic sleep variables arose for a number of reasons, including child refusal to wear the actigraph and actigraph failure (i.e., technical problems). At each age, there were no significant differences between children with and without actigraphy data in terms of child sex, family socioeconomic status, or total sleep problems as quantified by parent-report on the Child Sleep Habits Questionnaire (Owens, Spirito, & McGuinn, 2000) at 30 months. Missingness for the academic abilities variables was due to teachers opting not to ‘grade’ their students on the Mock Report Card.

Procedures

At the 30-, 36-, 42- and 54-month visits, children were provided with an actigraph to wear for a period of two weeks. At the 54-month visit, a research assistant administered several subscales of the Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Achievement, 3rd Edition (WJ-III; Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001) to the child in a quiet location. Approximately two weeks later, the child participated in a laboratory visit where several behavioral tasks were administered. After the laboratory visit, the child’s primary preschool teacher was asked to complete questionnaires assessing various domains of child adjustment (described below). All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Indiana University and the University of Nebraska.

Measures

Sleep.

Child sleep was assessed at each time point using a MicroMini Motionlogger actigraphs (Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc., Ardsley, NY) actigraph, a watch-like accelerometer that monitors minute-by-minute motor activity to determine sleep and wake patterns. Children wore actigraphs on their non-dominant wrists continuously for one to two weeks (M = 8.96 nights, range = 3 to 17; time points with <3 days of actigraphy data collection [<1% of cases] were excluded from analysis). Variability in the number of days that the child wore the actigraph was due to child noncompliance with wearing the device, family scheduling preferences for the laboratory visit (as actigraphs were returned to the research team during this visit), and actigraph failure. The child’s primary caregiver completed daily sleep diaries that were used to mark sleep and wake times, and any times the child did not wear the actigraph. Actigraph data were processed in the AW-2 software package (Motionlogger Analysis Software Package Action W-2 software, version 2.6.92, Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc) using the Sadeh algorithm, an algorithm that has been validated for use in early childhood (Sadeh, Sharkey, & Carskadon, 1994).

Based on previous principal components analysis (Staples, Bates, Petersen, McQuillan, & Hoyniak, 2019), the large number of AW-2 actigraph variables was summarized into four composite indexes. Composite indexes were formed by standardizing the actigraphy variables (based on sleep data across all assessments) and averaging them. These four composites – sleep duration, sleep timing, sleep variability, and sleep activity – represent broad dimensions of actigraphy that are often examined in the child sleep literature (Meltzer, Montgomery-Downs, Insana, & Walsh, 2012). The specific actigraphy variables included in each composite are listed in Table 1. A separate actigraphy variable that was not in any composite, sleep onset latency – minutes the child took to fall asleep – was also examined, as this aspect of sleep is frequently examined in the child sleep literature.

Table 1.

Actigraphy variables included in composites

| Sleep composite | Variable descriptions |

|---|---|

| Sleep duration | Average sleep period (min) |

| Average duration of time in bed (min) | |

| Average minutes asleep in bed | |

| Sleep timing | Average time of midsleep (HH:MM in 24‐hour time) |

| Average time of sleep onset (HH:MM in 24-hour time) | |

| Average bedtime (HH:MM in 24-hour time) | |

| Sleep variability | SD of time of sleep onset |

| SD of duration of time in bed | |

| SD of duration of sleep period | |

| SD of time of midsleep | |

| SD of bedtime | |

| SD of minutes asleep in bed | |

| Sleep activity | Average time (min) awake after sleep onset |

| SD of average minute to minute activity levels | |

| Average number of awakenings (lasting 5 min or more) | |

| Average duration (min) of longest wake episode (after sleep onset) | |

| Average per cent of active epochs (after sleep onset) |

Adjustment.

We assessed several major domains of child adjustment:

Behavioral adjustment:

Child behavioral adjustment in the context of the classroom was assessed using teacher reports on the Caregiver-Teacher Report Form for Ages 1½–5 (C-TRF; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) and the Child Behavior Scale (CBS; Ladd & Profilet, 1996). The C-TRF is an assessment of child externalizing (subscales: aggression and attention problems) and internalizing problems (subscales: anxious/depressed symptoms, emotional reactivity, and withdrawn behaviors). Teachers indicated whether each symptom was true of the child on a 3-point scale from 0 (not true) to 2 (very true or often true). For externalizing problems, Cronbach’s alpha values were .94 and .88 for the aggression and attention problems subscales, respectively. For internalizing problems, Cronbach’s alpha values were .72, .72, and .79 for the anxious/depressed, emotional reactivity, and withdrawn subscales, respectively. The CBS included two externalizing behavior subscales (hyperactive–distractible and aggressive with peers) and one internalizing behavior subscale (anxious–fearful). Teachers indicated whether each behavior applied to the child on 3-point scale from 0 (does not apply) to 2 (certainly applies). On both measures, higher scores indicated more internalizing and externalizing problems. Cronbach’s alpha values were .90, .89, and .59 for the hyperactive–distractible, peer aggression, and anxious–fearful subscales, respectively.

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations of the externalizing behavior and internalizing behavior variables are included in Tables S2 and S3. Given the relatively large correlations within the externalizing (.58 < r < .88) and internalizing (.30 < r < .62) domains, along with the theoretical correspondence of these variables, we created two separate composites, one for externalizing problems and one for internalizing problems, standardizing and averaging scores on the four variables in each domain.

Socioemotional skills:

Children’s socioemotional skills were assessed using teacher reports on the Social Competence Scale (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1990), the Teacher Checklist (Dodge & Coie, 1987), and the CBS. The Social Competence Scale measures prosocial behaviors and emotional regulation in the classroom. Teachers indicated whether each item described the child on a 5-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very well), with higher scores indicating better social competence. Cronbach’s alpha value for the Social Competence Scale was .98. We used a subscale of Teacher Checklist that measures child peer relations, indexing the extent to which the child is well-liked by his or her peers. Teachers indicated whether each item was true of the child on a 5-point scale from 1 (never true) to 5 (almost always true), with higher scores indicating that children were more well-liked by their classmates. Cronbach’s alpha value for this subscale of the Teacher Checklist was .83. From the CBS, we included a subscale assessing peer prosocial behavior and another indexing peer exclusion. Each CBS subscale was scored such that higher scores indicated higher levels of social competence (i.e., more prosocial behavior and less exclusion by peers). Cronbach’s alpha values were .86 and .88 for the peer prosocial behavior and peer exclusion subscales, respectively.

Descriptive statistics and correlations between each of the socioemotional variables are included in Table S4. Given the relatively large correlations (.38 < r < .71) and the theoretical correspondence of variables assessing socioemotional skills, we created a composite index of socioemotional skills, taking the average of scores on the four standardized socioemotional variables.

Academic/cognitive abilities:

Child academic/cognitive abilities were assessed using two subscales of the WJ-III and teacher ratings on the Mock Report Card (Pierce, Hamm, & Vandell, 1999). The WJ-III is a standardized assessment of children’s academic/cognitive abilities. To focus on early reading and math skills, the letter-word identification subscale and the applied problems subscale were administered. Raw scores on each of the subscales were used, with higher scores indicating better performance. Preschool teachers also completed the Mock Report Card, a questionnaire that assesses child academic abilities. The Mock Report Card assesses academic skills across a variety of categories, including Reading, Math, and Writing skills, with children’s skills rated from 1 (below average) to 5 (excellent).

Descriptive statistics and correlations among the five academic/cognitive variables are shown in Table S5. Given that the correlations across the WJ-III and Mock Report Card were relatively low (.20 < r < .47; see Table S5) and that these two scales measure separable constructs, we examined these measures separately. The two WJ-III scales were standardized and averaged to create an index of child cognitive abilities. The three Mock Report Card items were standardized and averaged to create an index of child academic abilities. Given the high level of missingness on the Mock Report Card (15%, due to teachers opting not to ‘grade’ their students), we included children in analysis if they had at least one of the three Mock Report Card items completed (Reading, Math, or Writing).

Analysis plan

We first examined Pearson correlations between child sleep at each age and the five adjustment composites. To minimize the number of associations examined, in further analyses, we included only the aspects of sleep that were consistently, significantly correlated (i.e., in the same direction and at multiple ages) with adjustment. Sleep variables that showed consistent associations with adjustment were next tested with growth curve models. We then examined if individual differences in growth curve trajectories were associated with individual differences in preschool adjustment outcomes. We fit growth curves in a structural equation modeling framework to examine change in the predictor variable (sleep) and the consequences of this change for the outcome variable (adjustment).

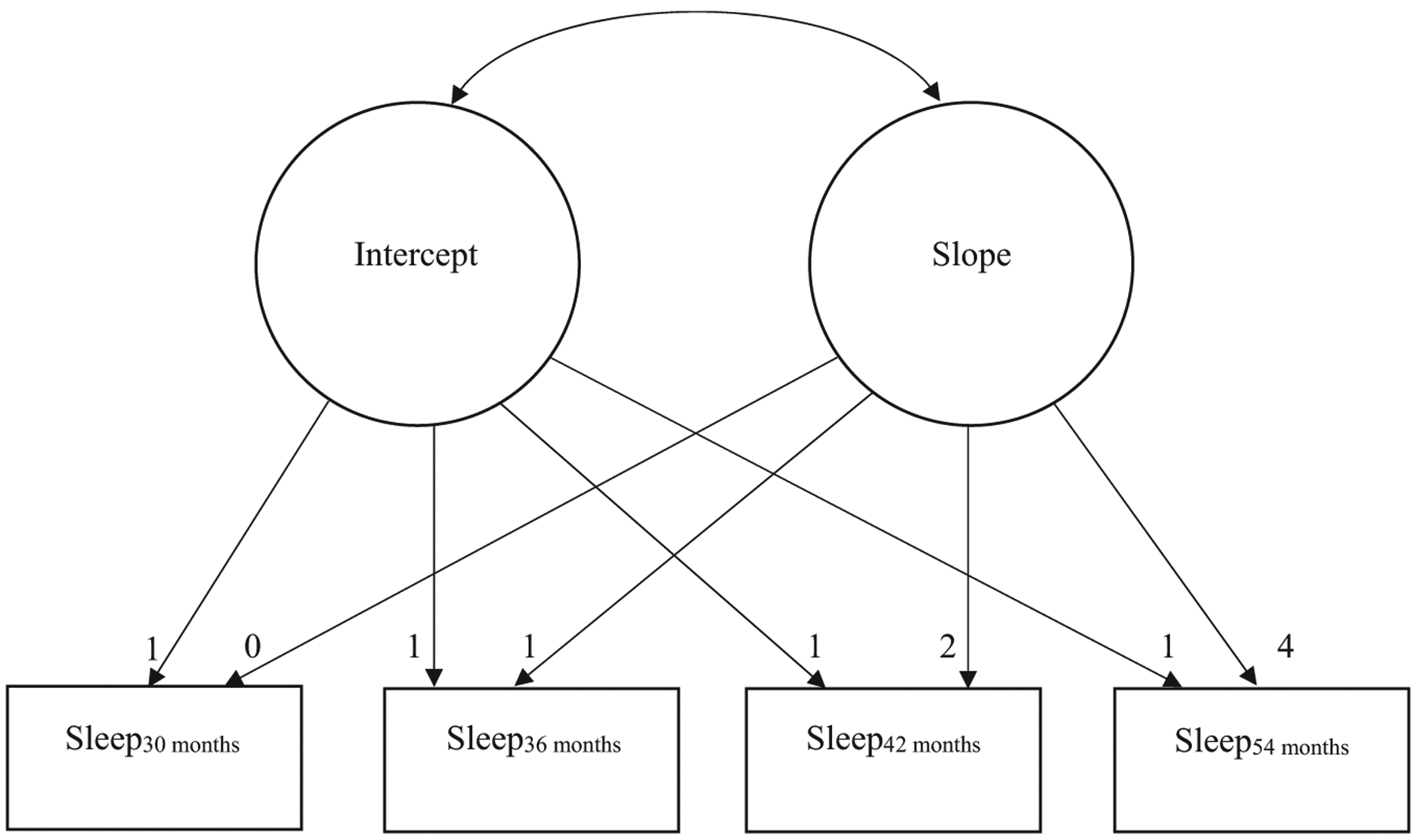

The latent growth curve models (LGCMs) generated a latent intercept parameter, quantifying the starting value of the sleep index at the first time point of assessment (30 months) and a latent slope parameter, quantifying changes in the sleep index across assessments (30 to 54 months). A depiction of our LGCM is included in Figure 1. Within this SEM framework, adjustment outcomes were then regressed on latent intercept and slope parameters. These models were then re-examined controlling for child sex, SES, and the number of months into the ‘preschool year’ that the child was at the time of the assessment. We included this month-of-preschool covariate because preschool assessments were scheduled based on the child’s age, rather than the time of school year. Consequently, the timing of the 54-month assessment could fall anywhere within the traditional preschool school year, and because exposure to formal schooling may affect adjustment or teacher-report measures of it, we controlled for this variable in analysis. Of note, the number of months the child had been in preschool at the time of the assessment was very modestly and not significantly correlated with any of the school readiness outcome variables (−.11 < r < .12, p’s > .05).

Figure 1.

Latent Growth Curve Models used to quantify growth trajectory of sleep indexes from 30 to 54 months

LGCM’s were fitted using the Lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012) in R (R Development Core Team, 2014). Full information maximum likelihood was used during model estimation to obtain parameter estimates in the presence of missing data. Following the recommendation of Preacher, Wichman, MacCallum, and Briggs (2008), we relied mainly upon the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck, 1993) index as a measure of model fit. RMSEA, a measure of absolute fit, estimates the amount of model misfit for the population, with values ranging from 0.00 to 1.00 and lower numbers indicating better model fit to the population. However, other common fit indexes are also reported for each model in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of latent growth curve models for sleep indexes

| (a) Sleep timing | (b) Sleep variability | (c) Sleep onset latency | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | P | B | SE | P | B | SE | p | |

| Means | |||||||||

| I | −00.10 | 0.08 | .23 | 0.03 | 0.07 | .67 | 40.13** | 2.22 | <.001 |

| S | −0.03 | 0.02 | .19 | −0.06* | 0.02 | .01 | −1.53** | 0.65 | .02 |

| (Co)Variances | |||||||||

| I | 0.59** | 0.10 | <.001 | 0.25** | 0.08 | .001 | 325.53 | 90.74 | <.001 |

| S | 0.02 | 0.01 | .08 | 0.004 | 0.01 | .74 | 5.86 | 13.51 | .67 |

| I ~ S | −0.04 | 0.02 | .08 | −0.03 | 0.02 | .29 | −32.57 | 25.87 | .21 |

| Fit statistics | |||||||||

| RMSEA | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.13 | ||||||

| CFI | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.84 | ||||||

| SRMR | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.12 | ||||||

I, Intercept; S, Slope; ~, Regressed on; RMSEA, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; SRMR, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual.

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics for the sleep variables at each age are provided in Table S6. Descriptive statistics for and correlations between the adjustment composites are provided in Table S7.

Correlations between sleep and adjustment

We began our analysis by examining correlations between child sleep, at each age, and the five adjustment composites (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlations between sleep and adjustment composites

| Externalizing behavior | Internalizing behavior | Socioemotional | Cognitive | Academic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 months | |||||

| Sleep duration | 0.02 | −0.10 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.14 |

| Sleep timing | −0.02 | 0.16 | −0.13 | −0.29** | −0.26** |

| Sleep variability | 0.05 | 0.25* | −0.15 | −0.10 | −0.30** |

| Sleep activity | 0.14 | 0.09 | −0.11 | 0.02 | −0.13 |

| Sleep latency | 0.16 | 0.18† | −0.17† | −0.06 | −0.28** |

| 36 months | |||||

| Sleep duration | −0.07 | −0.06 | −0.04 | 0.17 | 0.28** |

| Sleep timing | −0.01 | 0.21† | −0.10 | −0.33** | −0.22* |

| Sleep variability | −0.06 | 0.09 | −0.01 | −0.15 | −0.07 |

| Sleep activity | −0.02 | −0.09 | 0.24* | −0.11 | 0.06 |

| Sleep latency | 0.13 | 0.13 | −0.03 | 0.10 | −0.04 |

| 42 months | |||||

| Sleep duration | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.18† | 0.17 |

| Sleep timing | −0.16 | 0.12 | 0.03 | −0.28** | −0.23* |

| Sleep variability | 0.04 | 0.07 | −0.13 | 0.01 | −0.06 |

| Sleep activity | 0.15 | 0.06 | −0.09 | −0.10 | −0.09 |

| Sleep latency | −0.11 | 0.10 | 0.01 | −0.20† | −0.26* |

| 54 months | |||||

| Sleep duration | −0.19† | 0.003 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.08 |

| Sleep timing | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.21† | −0.24* | −0.12 |

| Sleep variability | 0.24* | 0.31** | −0.19† | −0.18† | 0.08 |

| Sleep activity | 0.02 | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.09 | 0.09 |

| Sleep latency | 0.12 | 0.14 | −0.13 | −0.09 | −0.04 |

p ≤ .10;

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01.

Behavioral adjustment.

For the externalizing problems composite, there was no consistent (i.e., in the same direction and at multiple ages) pattern of significant associations between sleep and externalizing problems. Only sleep variability at 54 months was significantly associated with externalizing problems (r = .24, p < .05), such that children getting more variable sleep from night to night showed more externalizing problems in the classroom. Given the general lack of significant findings, we did not further explore the longitudinal association between sleep and externalizing problems using LGCMs.

For the internalizing problems composite, there was a somewhat consistent (and significant at 30 and 54 months) association between sleep variability and internalizing problems (r = .25 and .31, p’s < .05, respectively), such that children with more variable sleep from night to night showed more internalizing problems in preschool. Therefore, we further explored the association between sleep variability and internalizing problems using LGCMs.

Socioemotional skills.

No consistent pattern of significant associations between sleep and socioemotional skills emerged. Only sleep activity at 36 months showed a significant association with socioemotional skills (r = .24, p < .05), with children with more activity during the sleep period showing better socioemotional skills in preschool. Given this general lack of significant findings, we did not further explore the longitudinal association between sleep and socioemotional skills using LGCMs.

Academic/cognitive abilities.

For the cognitive composite (comprised of WJ-III variables), there was a consistent, significant association between sleep timing and cognitive abilities at each age (−.23 < r < −.33, p’s < .05), such that children with later bedtimes across toddlerhood and into preschool showed poorer cognitive abilities in preschool. For the academic composite (comprised of Mock Report Card variables), there was a consistent, significant association between sleep timing and academic abilities at 30, 36, and 42 months (−.23 < r < −.26, p’s < .05), such that children with later bedtimes showed poorer academic abilities in preschool. Additionally, there was a significant association between onset latency and academic abilities at 30 and 42 months, such that children with longer sleep latencies showed poorer teacher-rated academic abilities in preschool. We used Latent Growth Curve Modeling to further explore the association between cognitive abilities and sleep timing, as well as the association between academic abilities and two sleep indexes – sleep timing and sleep onset latency.

Latent growth curve models

Sleep variability and internalizing problems.

The sleep variability data were adequately represented by a LGCM with a random intercept and a linear slope (RMSEA = 0.05; see Table 3b). The mean value of the intercept for sleep variability was not significant, indicating that it was not reliably different from zero (which was expected as this is a standardized variable). The mean value of the slope for sleep variability was significant and negative, suggesting that children’s sleep became less variable, linearly, across time. The variance component of the intercept was significant, suggesting between-subject variability in intercept values. Neither the variance component for the slope nor the covariance between the intercept and slope components was significant.

We then examined the association between the intercept and slope estimates from the LGCM and the internalizing problems composite. This model fit the data adequately (RMSEA = 0.07; see Table 4a). Overall, findings indicate a significant, positive association between the latent intercept and the internalizing problems composite, suggesting that children with more variable sleep at the 30-month assessment had more internalizing problems in preschool. There was no significant association between the latent slope and the internalizing problems composite. The pattern of findings remained statistically significant when the three covariates (sex, SES, and months in school) were controlled (see Table S8a). Of note, none of the covariates were associated with the latent intercept or slope for sleep variability.

Table 4.

Results of latent growth curve models with adjustment abilities. All estimates presented are standardized

| (a) Sleep variability and internalizing problems | (b) Sleep timing and cognitive abilities | (c) Sleep timing and academic abilities | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | p | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | |

| Means | |||||||||

| I | .05 | 0.13 | .68 | −.12 | 0.10 | .23 | −.12 | 0.10 | .23 |

| S | −.68 | 0.63 | .28 | −.21 | 0.17 | .22 | −.22 | 0.17 | .20 |

| (Co)Variances | |||||||||

| I | .94** | 0.06 | <.001 | .88** | 0.06 | <.001 | .90** | 0.07 | <.001 |

| S | .95** | 0.14 | <.001 | .99** | 0.03 | <.001 | .97** | 0.06 | <.001 |

| I ~ S | −.70* | 0.36 | .05 | −.39* | 0.16 | .01 | −.36* | 0.16 | .02 |

| Regressions | |||||||||

| I ~ Internal | .25* | 0.13 | .04 | ||||||

| S ~ Internal | .21 | 0.31 | .50 | ||||||

| I ~ Cognitive | −0.35** | .09 | <.001 | ||||||

| S ~ Cognitive | 0.08 | .16 | .61 | ||||||

| I ~ Academic | −0.32** | .10 | .001 | ||||||

| S ~ Academic | 0.19 | .17 | .27 | ||||||

| Fit statistics | |||||||||

| RMSEA | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.01 | ||||||

| CFI | 0.91 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| SRMR | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.05 | ||||||

I, Intercept; S, Slope; ~, Regressed on; Internal, Internalizing; RMSEA, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; SRMR, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual.

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01.

Sleep timing and academic/cognitive abilities.

The sleep timing data were adequately represented by a LGCM with a random intercept and a linear slope (RMSEA = 0.06; see Table 3a). Neither the intercept nor the slope mean value was significant, indicating that they were not reliably different from zero. Despite a nonsignificant mean slope, we retained it in our LGCM due to (a) our theoretical interest in the association between individual differences in the slope value and the school readiness composite, and (b) the adequate fit of the model. The variance component of the intercept was significant, indicating that there was substantial between-child variability in intercept values for this index. Neither the variance component for the slope nor the covariance between the intercept and slope components was significant.

We then examined the association between the intercept and slope estimates from the sleep timing LGCM and cognitive abilities. This model fit the data well (RMSEA = 0.02; see Table 4b). Overall, findings indicated a significant, negative association between the latent intercept and cognitive abilities, suggesting that children with later sleep timing at the 30-month assessment had poorer cognitive abilities in preschool. There was no significant association between the latent slope and the cognitive abilities composite. When re-examined, controlling for the three covariates, the pattern of findings held (see Table S8b). However, child SES and number of months in school were both also significantly associated with the latent intercept, such that children from lower SES backgrounds and children who had been in school for fewer months at the time of preschool assessment had later sleep timing at 30 months. Additionally, child SES was significantly associated with the latent slope, such that children from lower SES backgrounds showed faster rates of change in sleep timing. However, as the slope was not significant in the overall model, this finding will not be interpreted further.

Next, we examined the association between the intercept and slope estimates from the sleep timing LGCM and academic abilities. This model fit the data well (RMSEA = 0.01; see Table 4c). Overall, findings indicated a significant, negative association between the latent intercept and academic abilities, suggesting that children with later sleep timing at the 30-month assessment had poorer academic abilities in preschool. There was no significant association between the latent slope and the academic abilities composite. In a model controlling for the three covariates, the pattern of findings held, and the pattern of significant associations between the covariates and latent intercept/slope were identical to those described above for cognitive abilities (see Table S8c).

Sleep onset latency and academic abilities.

The sleep onset latency data were poorly represented by LGCMs with both a random intercept or a random intercept and a linear slope (RMSEA = 0.13 for both; see Table 3c for LGCM with random intercept and linear slope). Thus, we did not further model the association between sleep onset latency and academic abilities.

Discussion

In the current study, we examined how child sleep, measured objectively and longitudinally across two years of development (from 30 to 54 months), was associated with adjustment at 54 months across the domains of externalizing problems, internalizing problems, socioemotional skills, cognitive abilities, and academic abilities. The current study improves our understanding of how developmental changes in sleep, common in early childhood, are associated with later adjustment outcomes.

Sleep and externalizing problems

Contrary to our expectations, we found few significant associations between child sleep and externalizing problems across time. The only significant association occurred at 54 months and suggested that children with more variable sleep schedules showed higher levels of concurrent externalizing problems. To our knowledge, no previous studies have demonstrated a direct association between actigraphically measured sleep problems and externalizing problems in early childhood. However, a number of studies have shown an association between parent-reported sleep and externalizing problems in early childhood (Bates et al., 2002; Goodlin-Jones, Tang, et al., 2009; Goodlin-Jones, Waters, et al., 2009; Hiscock et al., 2007; Lavigne et al., 1999; Quach et al., 2018; Scharf et al., 2013), raising the possibility that these associations were due in part to shared method variance. Additional research, perhaps focusing on externalizing problems in both a state (e.g., stable externalizing problems) and trait (e.g., day to day fluctuations in problem behaviors) framework could clarify the contradictions in this literature by determining the circumstances under which an association between sleep and externalizing problems emerge.

Sleep and internalizing problems

Consistent with our expectations, we found an association between sleep variability and internalizing problems, such that children with more variable sleep schedules had more internalizing problems (e.g., anxious, depressed, and withdrawn behaviors). Growth curve analysis showed that children with more variable sleep schedules at 30 months (the first time point of assessment) had more internalizing problems in preschool, but changes in the levels of variability of children’s sleep schedules across this era of development were not associated with individual differences in internalizing problems in preschool. These findings held when controlling for child sex, SES, and months in school. Researchers have proposed a bidirectional association between sleep problems and internalizing symptoms, potentially due to fact that the same neural systems and psychobiological processes (e.g., arousal and vigilance) are thought to underlie both sleep and internalizing problems, particularly anxiety (Leahy & Gradisar, 2012). However, research findings pertaining to this bidirectional association have been variable, suggesting the complicated nature of the association between sleep and internalizing symptoms (Leahy & Gradisar, 2012; Quach et al., 2018). In the current study, we were unable to assess the directionality of the association between sleep and internalizing problems, but future studies should include an explicit focus on the bidirectional association between night-to-night sleep variability and internalizing problems.

Sleep and socioemotional skills

Contrary to our expectations, no consistent, significant associations between sleep and children’s socioemotional skills emerged. Few studies have examined the association between sleep and school-related socioemotional abilities in early childhood. Those that have suggest an association between sleep duration and child social competencies (Tso et al., 2016; Vaughn et al., 2015) or between increased sleep problems and poorer emotional regulation skills as reported by parents and teachers (Williams et al., 2015, 2016). These findings were not replicated in the current study. However, our findings are similar to those of Mindell, Leichman, DuMond, and Sadeh (2017) who found no significant association between sleep in infancy and social competence in toddlerhood. The construct of socioemotional skills is comprised of various sub-constructs and can be conceptualized in a number of different ways (e.g., peer relationships, emotional functioning in the classroom, and work habits) depending on the age of the child. As such, differences in the way socioemotional skills are quantified across studies could be contributing to discrepant findings in this literature. Increased systematic research on this question is needed to understand the unfolding developmental association between sleep and socioemotional abilities.

Sleep and academic/cognitive abilities

Consistent with our expectations, results indicated that the most robust association between sleep and adjustment occurred in the academic/cognitive abilities domain. Due to relatively low correlations across indexes of cognitive abilities and academic skills, we opted to examine these two constructs separately; however, the patterns of associations for these constructs were largely the same. Sleep timing was consistently associated with both cognitive abilities, as measured using a standardized assessment (the WJ-III), and academic abilities, as reported by preschool teachers on the Mock Report Card. Correlation analyses suggested a significant, negative association between sleep timing at 30, 36, 42, and 54 months and cognitive and academic abilities in preschool, such that children with later sleep schedules at 30, 36, 42, and 54 months had poorer cognitive abilities at 54 months and children with later sleep schedules at 30, 36, and 42 months had poorer academic abilities at 54 months. Further growth curve analyses suggested that children with later sleep timing at the 30-month assessment had poorer cognitive and academic abilities in preschool. However, changes in the timing of sleep across this era of development did not predict either cognitive or academic abilities in preschool. The cognitive and academic findings both held when controlling for child sex, SES, and months in school. However, child SES and months in school (the number of months the child was enrolled in preschool at the time of the 54-month assessment) were both also associated with sleep timing at 30 months, such that children from lower SES backgrounds and children who had been in school for fewer months at the time of the preschool assessment had later sleep timing at 30 months. Importantly, the association between sleep timing and academic/cognitive abilities held when controlling for child SES, suggesting that these results are not simply attributable to the influence of SES on both sleep and academic/cognitive abilities. These findings join a literature suggesting that young children with increased sleep problems show poorer cognitive and academic abilities (Hoyniak et al., 2018; Jung et al., 2009; Nelson et al., 2015; Quach et al., 2009; Tso et al., 2016; Vaughn et al., 2015).

Sleep across early childhood

LGCMs of sleep timing and variability did not reflect significant changes in either index across time. These findings stand in contrast to research suggesting that there are significant developmental changes in both sleep problems and normative sleep patterns across childhood (Galland et al., 2012; Gregory & O’Connor, 2002; Price et al., 2014), with sleep problems tending to decrease across early childhood (Petit et al., 2007; Williamson, Mindell, Hiscock, & Quach, 2019) and stabilizing thereafter in middle childhood (Williamson et al., 2019). However, recent evidence suggests that sleep timing may be stable, at least across middle childhood and adolescence (Kuula et al., 2018). Our findings complement and extend these findings, suggesting that sleep timing and variability might emerge as a stable individual difference as early as toddlerhood. Although not explored in the current study, several environmental factors may play a role in determining sleep timing and variability in early childhood, including parental attitudes about child sleep needs, family organization and chaos, parent work schedules (e.g., swing shift or night shift work), and parent–child bedsharing. These environmental factors may represent relatively fixed, stable family characteristics, thereby reducing the likelihood that sleep timing and variability change significantly across development. Future research is needed to understand how developmental changes in sleep differ based on the domain of sleep under consideration (e.g., consolidation, duration, and timing).

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of the current study is that it included actigraphic measures of sleep and systematically considered variables across the major domains of sleep difficulties. Of the five aspects of sleep examined, sleep timing and sleep variability had the most robust associations with adjustment outcomes. This finding corresponds with a number of other findings, demonstrating the importance of timing of, and night-to-night variability in, a child’s sleep schedule for predicting a variety of adjustment outcomes in early childhood (e.g., Hoyniak et al., 2018). Although other aspects of sleep, such as duration, are more commonly assessed in studies focusing on sleep in childhood, increased attention has recently been allotted to additional aspects of sleep including night-to-night variability and timing (e.g., Becker et al., 2017). Our findings suggest that it is important for researchers to examine a comprehensive range sleep variables, as using only one or two actigraphy indexes may not be sufficient to identify significant patterns.

The relatively small and highly educated sample in this study potentially limits the generalizability of these findings, and it will be important to replicate these results in a larger and more diverse sample. Additionally, as we timed our preschool assessments based on child age rather than time in the school year, some children had more exposure to the preschool environment than others. To address this potential limitation, we controlled for exposure to preschool in our models. Future research could compare our approach to one that fixes the time of school year during which assessments are conducted and controls for the age of the child.

Conclusion

The current study demonstrated an association between sleep across early childhood and several domains of adjustment in preschoolers. High levels of sleep variability at 30 months were associated with higher levels of internalizing, but not externalizing problems in preschool. Later child sleep schedules were associated with poorer cognitive and academic abilities. However, individual differences in changes in sleep indexes across toddlerhood into preschool were not associated with individual differences in adjustment outcomes. Additionally, several traditionally examined indexes of sleep, including sleep duration, were not reliably associated with adjustment outcomes across domains. These findings underscore the importance of simultaneously considering multiple aspects of sleep (e.g., duration, timing, and variability) when examining the association between sleep and adjustment in early childhood. Our results also demonstrate the importance of considering individual differences in sleep when examining the development of internalizing problems and academic/cognitive abilities in early childhood. Ample research suggests that sleep problems in early childhood are modifiable by relatively brief and cost-effective sleep interventions (Meltzer & Mindell, 2014; Mindell, Kuhn, Lewin, Meltzer, & Sadeh, 2006). Our findings suggest that using such interventions to address sleep problems, particularly problems related to child sleep schedules and habits (i.e., sleep timing and variability), may be impactful for decreasing internalizing problems and academic/cognitive difficulties in early childhood.

Supplementary Material

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article:

Table S1. Percent missing at each age for each variable included in analysis.

Table S2. Descriptive statistics and bivariate Pearson correlations between externalizing behavioral adjustment variables.

Table S3. Descriptive statistics and bivariate Pearson correlations between internalizing behavioral adjustment variables.

Table S4. Descriptive statistics and bivariate Pearson correlations between socioemotional variables.

Table S5. Descriptive statistics and bivariate Pearson correlations between academic variables.

Table S6. Descriptive statistics for the sleep variables at each age.

Table S7. Descriptive statistics and correlations between school readiness composites.

Table S8. Results of latent growth curve models including co-variates. All estimates presented are standardized.

Key points.

Sleep problems in early childhood are associated with poorer behavioral and cognitive development, but this research has mainly relied on cross-sectional studies and subjective reports of sleep.

We found an association between objectively measured sleep across early childhood and several domains of adjustment in preschoolers.

Better sleep at 30 months of age was associated with fewer internalizing problems and better academic/cognitive development in preschoolers, but longitudinal changes in sleep were not associated with adjustment outcomes. These findings underscore the importance of considering individual differences in sleep in interventions aimed at improving adjustment in early childhood.

Acknowledgements

The authors have declared that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

References

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla L (2000). ASEBA preschool forms & profiles: An integrated system of multi-informant assessment. Burlington, VT: Aseba. [Google Scholar]

- Astill RG, Van der Heijden KB, Van IJzendoorn MH, & Van Someren EJW (2012). Sleep, cognition, and behavioral problems in school-age children: A century of research meta-analyzed. Psychological Bulletin, 138, 1109–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates JE, Viken RJ, Alexander DB, Beyers J, & Stockton L (2002). Sleep and adjustment in preschool children: Sleep diary reports by mothers relate to behavior reports by teachers. Child Development, 73, 62–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe DW (2011). Cognitive, behavioral, and functional consequences of inadequate sleep in children and adolescents. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 58, 649–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier A, Beauchamp MH, Bouvette Turcot AA, Carlson SM, & Carrier J (2013). Sleep and cognition in preschool years: Specific links to executive functioning. Child Development, 84, 1542–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, & Cudeck R (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit In Bollen KA & Long JS (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (Vol. 154, pp. 136–162). Newbury Park, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group (CPPRG) (1990). Social Competence Scale (Teacher Version). Fast Track Project Website. [Google Scholar]

- Cremone A, Jong DM, Kurdziel LBF, Desrochers P, Sayer A, LeBourgeois MK, … & McDermott JM (2018). Sleep tight, act right: Negative affect, sleep and behavior problems during early childhood. Child Development, 89, e42–e59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayyat EA, Spruyt K, Molfese DL, & Gozal D (2011). Sleep estimates in children: Parental versus actigraphic assessments. Nature and Science of Sleep, 3, 115–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, & Coie JD (1987). Social-Information-Processing Factors in reactive and proactive aggression in children’s peer groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 1146–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galland BC, Taylor BJ, Elder DE, & Herbison P (2012). Normal sleep patterns in infants and children: a systematic review of observational studies. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 16, 213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodlin-Jones BL, Tang K, Liu J, & Anders TF (2009). Sleep problems, sleepiness and daytime behavior in preschool-age children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50, 1532–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodlin-Jones BL, Waters S, & Anders TF (2009). Objective sleep measurement in typically and atypically developing preschool children with ADHD-like profiles. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 40, 257–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory AM, & O’Connor TG (2002). Sleep problems in childhood: A longitudinal study of developmental change and association with behavioral problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 964–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory AM, & Sadeh A (2012). Sleep, emotional and behavioral difficulties in children and adolescents. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 16, 129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiscock H, Canterford L, Ukoumunne OC, & Wake M (2007). Adverse associations of sleep problems in Australian preschoolers: National population study. Pediatrics, 119, 86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB (1975). Four factor index of social status. Unpublished work.

- Hoyniak CP, Bates JE, Staples AD, Rudasill KM, Molfese DL, & Molfese VJ (2018). Child sleep and socioeconomic context in the development of cognitive abilities in early childhood. Child Development, 28, 1568–1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K, & Harrison Y (2001). Frontal lobe function, sleep loss and fragmented sleep. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 5, 463–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung E, Molfese VJ, Beswick J, Jacobi-Vessels J, & Molnar A (2009). Growth of cognitive skills in preschoolers: Impact of sleep habits and learning-related behaviors. Early Education Development, 20, 713–731. [Google Scholar]

- Kushida CA, Chang A, Gadkary C, Guilleminault C, Carrillo O, & Dement WC (2001). Comparison of actigraphic, polysomnographic, and subjective assessment of sleep parameters in sleep-disordered patients. Sleep Medicine, 2, 389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuula L, Pesonen A-K, Merikanto I, Gradisar M, Lahti J, Heinonen K, … & Räikkönen K (2018). Development of late circadian preference: sleep timing from childhood to late adolescence. The Journal of Pediatrics, 194, 182–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, & Profilet SM (1996). The Child Behavior Scale: A teacher-report measure of young children’s aggressive, withdrawn, and prosocial behaviors. Developmental Psychology, 32, 1008–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Lam JC, Mahone EM, Mason T, & Scharf SM (2011). The effects of napping on cognitive function in preschoolers. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 32, 90–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne JV, Arend R, Rosenbaum D, Smith A, Weissbluth M, Binns HJ, & Christoffel KK (1999). Sleep and behavior problems among preschoolers. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 20, 164–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leahy E, & Gradisar M (2012). Dismantling the bidirectional relationship between paediatric sleep and anxiety. Clinical Psychologist, 16, 44–56. [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer LJ, & Mindell JA (2014). Systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions for pediatric insomnia. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39, 932–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer LJ, Montgomery-Downs HE, Insana SP, & Walsh CM (2012). Use of actigraphy for assessment in pediatric sleep research. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 16, 463–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell JA, Kuhn B, Lewin DS, Meltzer LJ, & Sadeh A (2006). Behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. Sleep, 29, 1263–1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell JA, Leichman ES, DuMond C, & Sadeh A (2017). Sleep and social-emotional development in infants and toddlers. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 46, 236–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TD, Nelson JM, Kidwell KM, James TD, & Espy KA (2015). Preschool sleep problems and differential associations with specific aspects of executive control in early elementary school. Developmental Neuropsychology, 40, 167–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens J (2007). Classification and epidemiology of childhood sleep disorders. Sleep Medicine Clinics, 2, 353–361. [Google Scholar]

- Owens JA, Spirito A, & McGuinn M (2000). The children’s sleep habits questionnaire (CSHQ): Psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children. Sleep, 23, 1043–1052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce KM, Hamm JV, & Vandell DL (1999). Experiences in after-school programs and children’s adjustment in first-grade classrooms. Child Development, 70, 756–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Wichman AL, MacCallum RC, & Briggs NE (2008). Latent growth curve modeling In Lao TF (Ed.), Series: Quantitative applications in the social sciences. Thousand. Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Price AM, Brown JE, Bittman M, Wake M, Quach J, & Hiscock H (2014). Children’s sleep patterns from 0 to 9 years: Australian population longitudinal study. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 99, 119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quach JL, Hiscock H, Canterford L, & Wake M (2009). Outcomes of child sleep problems over the school-transition period: Australian population longitudinal study. Pediatrics, 123, 1287–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quach JL, Nguyen CD, Williams KE, & Sciberras E (2018). Bidirectional associations between child sleep problems and internalizing and externalizing difficulties from preschool to early adolescence. JAMA Pediatrics, 172, e174363–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team (2014). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Available from: http://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A, Sharkey KM, & Carskadon MA (1994). Activity-based sleep-wake identification: An empirical test of methodological issues. Sleep, 17, 201–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf RJ, Demmer RT, Silver EJ, & Stein REK (2013). Nighttime sleep duration and externalizing behaviors of preschool children. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 34, 384–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short MA, & Banks S (2014). The functional impact of sleep deprivation, sleep restriction, and sleep fragmentation In Bianchi MT (Ed.), Sleep deprivation and disease (pp. 13–26). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Staples AD, & Bates JE (2011). Children’s sleep and cognitive and behavioral adjustment In El-Sheikh M (Ed.), Sleep and development: Familial and socio-cultural considerations (pp. 133–164). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Staples AD, Bates JE, Petersen IT, McQuillan ME, & Hoyniak C (2019). Measuring sleep in young children and their mothers: Identifying actigraphic sleep composites. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 43, 278–285. 10.1177/0165025419830236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikotzky L, & Sadeh A (2001). Sleep patterns and sleep disruptions in kindergarten children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30, 581–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tononi G, & Cirelli C (2014). Sleep and the price of plasticity: From synaptic and cellular homeostasis to memory consolidation and integration. Neuron, 81, 12–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tso W, Rao N, Jiang F, Martin Li A, Lee S-L, Ho FK, … & Ip P (2016). Sleep duration and school readiness of Chinese preschool children. The Journal of Pediatrics, 169, 266–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn BE, Elmore-Staton L, Shin N, & El Sheikh M (2015). Sleep as a support for social competence, peer relations, and cognitive functioning in preschool children. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 13, 92–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KE, Berthelsen D, Walker S, & Nicholson JM (2015). A developmental cascade model of behavioral sleep problems and emotional and attentional self-regulation across early childhood. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 15, 1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KE, Nicholson JM, Walker S, & Berthelsen D (2016). Early childhood profiles of sleep problems and self-regulation predict later school adjustment. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 86, 331–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson AA, Mindell JA, Hiscock H, & Quach J (2019). Child sleep behaviors and sleep problems from infancy to school-age. Sleep Medicine, 63, 5–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock RW, McGrew KS, & Mather N (2001). Woodcock Johnson tests of cognitive ability III. Rolling Meadows IL: Riverside. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article:

Table S1. Percent missing at each age for each variable included in analysis.

Table S2. Descriptive statistics and bivariate Pearson correlations between externalizing behavioral adjustment variables.

Table S3. Descriptive statistics and bivariate Pearson correlations between internalizing behavioral adjustment variables.

Table S4. Descriptive statistics and bivariate Pearson correlations between socioemotional variables.

Table S5. Descriptive statistics and bivariate Pearson correlations between academic variables.

Table S6. Descriptive statistics for the sleep variables at each age.

Table S7. Descriptive statistics and correlations between school readiness composites.

Table S8. Results of latent growth curve models including co-variates. All estimates presented are standardized.