Abstract

Among the extraordinary shocks to household life caused by the Covid-19 pandemic was the sudden shift to distance learning in K-12 schools. Gone were Monday through Friday routines of school day, extracurricular activities, and evening homework; schools scrambled to launch alternative delivery systems, expecting parents to step in and spend significant amounts of time helping children continue to learn. This study examines the sudden shift to distance learning using data from U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey. Conducted weekly from April through July 2020, the survey tracked COVID-related shocks to employment, health, food and housing security, and education in the U.S. population. We use Pulse data on 200,000 households with K-12 children to examine how school systems shifted, how parents stepped up and spent time helping children learn, how parental time inputs varied with parent education, and how education changes intersected with other pandemic shocks, including job loss and food insecurity. We find that parents and children spent significantly more time in learning activities when their schools provided diversified educational inputs, especially live contact time with teachers; live contact hours also facilitated children learning on their own. Given the type of alternative schooling, less educated parents spent no less time helping children than better educated parents, although they faced significantly more problems with computer and internet access. Thus, parents generally tried to help children continue learning in the pandemic, albeit with potentially wide variation in the resources they could supply to mitigate the drop in learning.

JEL codes: D1 household behavior and family economics, J13 children, I21 analysis of education, I24 education and inequality, I18 public health

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic caused major disruptions in the supply and delivery of education. In the U.S., most primary and secondary (K-12) schools sent children home in mid-March 2020, with uncertain plans for when classes would resume.1 By mid-April most states had terminated in-person classes for the rest of the academic year (Education Week 2020a). Many school districts pivoted to some form of remote learning to help students try to stay on track for their grade level. The method and intensity of continued education varied widely by state and school district, reflecting state-level directives and local school system decisions and resources. Some school systems offered options for online, print materials, both or neither, with some having teachers hold classes online. Some schools provided extra resources needed to support distance learning such as access to laptops, tablets, and the internet (Schwartz 2020).

These disruptions in education supply are expected to result in significant setbacks for students. A Brown University study projected that students in grades 3 through 8 would start the 2020–21 academic year behind by almost half a year relative to grade-level expectations, having achieved only 63–68% of the expected learning gains in reading and only 37–50% of the expected gains in math (Kuhfeld et al. 2020). This parallels evidence from an online program, Zearn, used by many schools to teach and reinforce math skills, which shows that relative to pre-pandemic learning levels, students’ learning plummeted after children were sent home in mid-March; although learning progress recovered somewhat in April, it then plunged through the end of June (Chetty et al. 2020; Yglesias 2020). There are substantial concerns that, especially for children in younger grades, educational disruptions could have long-run effects on cognitive development and life opportunities. For example, one study found that educational disruptions in World War II significantly affected the earnings of people who were young at that time some 40 years later (Ichino and Winter‐Ebmer 2004).

It has been an important concern that households differ in the time and resources they can bring to the switch to distance learning.2 Previous research has shown that college-educated parents tend to spend more time helping children with homework than less educated counterparts, and that black and Hispanic parents spend less time than white non-Hispanic parents.3 Various reasons for these gradients have been explored, including parents’ “preferences” for children’s educational achievements, different returns to parental time providing schoolwork help, prevalence of single-parent households in which parental time is especially scarce, and/or social norms in school systems.4 Children in higher-income households are also more likely to have access to electronic devices (computer, laptop, or tablet) and high-speed internet (Garcia et al. 2020), and/or to attend schools that are relatively “wired”—factors that would facilitate a sudden shift to distance learning in higher-income communities and complicate them elsewhere. Thus, the Zearn data mentioned above show that children in higher-income zip codes sustained some math learning through May 2020, whereas math learning almost stopped for students in middle- and lower-income zip codes after getting sent home in March (Chetty et al. 2020; Yglesias 2020). Thus, households’ unequal access to resources to support distance learning may work to exacerbate inequities in children’s human capital accumulation that existed before the pandemic.

At the same time, the Covid-19 pandemic has involved some substantial shocks to parents’ time and income that intersect with new demands on their time to help children with schoolwork (Bacher-Hicks et al. 2020). Labor-market data show the extraordinary increases in unemployment associated with pandemic-related business closures in spring 2020 fell disproportionately on women and on workers without four-year college degrees (Fairlie et al. 2020). As low- and moderate-income U.S. households commonly do not have savings set aside for a rainy day (Beshears et al. 2020), job loss in the pandemic economy can lead relatively quickly to financial distress and food and housing insecurity. But also, for some, unexpected increases in parent time at home coincided with new expectations that parents help maintain children’s learning in a distance format. Here the parent-education gradient with respect to time helping children may invert or at least flatten: as better educated parents have much lower rates of job loss and much better ability to work from home, they are much less likely to have had a “positive” shock to time availability and rather have confronted new issues of “parenting while working”.

This paper examines how U.S. households dealt with the Spring 2020 educational disruptions caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, investigating time spent by parents helping children sustain learning despite substantial reductions in school-provided inputs. We use newly available data on 200,000 families with K-12 children from the Household Pulse Survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau. Launched in late April 2020, the Pulse Survey has collected weekly data from large, nationally representative samples of U.S. households, asking questions about effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, including questions about job loss, food and housing security, education disruptions, health and mental health, receipt of income support, and household financial distress. We first examine predictors of parent hours spent in teaching activities with their children, including household characteristics, features of the alternative delivery systems their schools put in place, and other COVID-related shocks experienced by the household, notably job loss. Next, we examine whether predictors of parent hours have differed by parental education, with a specific interest in understanding how more and less advantaged households may have differed in their abilities to navigate given types of distance learning arrangements. Finally, we analyze how time spent by children in learning activities on their own was affected by parental time inputs and school-system arrangements, as arrangements that facilitate independent learning valuably conserve scarce parental time.

Our results show that school and parental resources to support distance learning were unequally distributed across U.S. households, with online learning options widespread in some parts of the country and patchy elsewhere. As expected, problems with access to computers and the internet for educational purposes have been far more common among less-advantaged households and in parts of the U.S. with lower per capita income. However, we also find that increases in school-system inputs increased parents’ time helping children in ways that did not differ substantially by the parent’s level of educational attainment. In particular, adding live teacher hours to online learning platforms increased parent hours at least as much among households without high school degrees as they did among households with 4-year college degrees. This suggests, when parents had access to similar resources, they contributed to sustaining their children’s learning to similar degree—although less educated parents were more often in situations where school-provided inputs were low and the productivity of their time helping their children was held down by lack of technology. We find that parents of K-12 children generally spent considerable amounts of time helping children learn in the Covid-19 pandemic: 72% of households with K-12 children said they spent time in teaching activities with children in the previous week, with an average total time of 2.6 h per school day. We also find that, other things being equal, parents spent more time helping children when the school provided more resources such as online teaching and paper resources. Most children also spent time working by themselves in learning activities, and they spent more time working independently when their parents and teachers had spent time working with them too. In other words, both parent time and live teacher hours significantly increased independent study hours by children, although having one or the other still had a significant positive effect on children’s study time. Altogether, our results suggest that, in the Covid-19 pandemic in spring 2020, U.S. households broadly aimed to provide time inputs into their children’s learning that would complement those provided by schools, although it is too soon to say how effective these new levels and combinations of inputs have been in sustaining children’s human capital accumulation in this extraordinary time.

Data and specification

Household Pulse Survey

The Household Pulse Survey is a digitally administered survey that uses an address-based sample frame to collect nationally representative information on effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on U.S. households.5 Sample households are drawn from the Census Bureau’s Master Address File (MAF), which contains cell phone and email addresses linked to 144 million U.S. residential addresses (Fields et al. 2020).6 Households are contacted by email, cellphone, or both;7 the first household member who responds is sent an email with a link to an internet survey that is intended to take less than 20 min to complete. At the time this paper was written, Pulse data were available for the 10 weeks from April 23–May 5, 2020 (about 5–6 weeks after pandemic-related school closures) to July 2–7, 2020 (after the end of the 2019–20 academic year). An average of 91,000 households responded to the survey each week. Although the survey response rate is low by federal survey standards (3.8%), the Census Bureau is able to link address-based information from the MAF to data from other Census surveys, providing a basis for computing sample weights that adjust for differential nonresponse and can be used by analysts to make the sample data representative of U.S. households as a whole.8

In the interest of keeping the survey brief, many questions collect summary information for the household as a whole, such as “Have you or has anyone in your household experienced a loss of employment income since March 13, 2020?” Detailed information on age, education, marital status, race, ethnicity, and employment status is collected for the survey respondent only; only general information on household composition (number of adults, number of children under 18) is collected. Thus, the Pulse data cannot be used to study responses within the household to pandemic-caused shocks to employment, health, and education.9 Yet the survey’s exact focus on the pandemic’s effects, combined with its unique sample design, make it a source of nationally representative household level information that is unavailable elsewhere.

On the subject of educational disruptions, the Pulse questionnaire asks, “How has the coronavirus pandemic affected how the children in this household received education?” Possible replies were: school was canceled, classes moved to distance learning using online resources, classes moved to distance learning using paper materials sent home to children, classes changed in some other way, and there was no change because schools did not close; more than one reply could be selected.10 Respondents were also asked how many hours that children had live contact with teachers via internet or phone in the past week, and about children’s access to the internet and access to a computer or other digital device that could be used for educational purposes.

To measure household time spent on children’s education, respondents were asked, “Including hours spent during weekdays and weekends, about how many hours did household members spend on ALL teaching activities with the children in this household during the last 7 days? Enter number of hours. (If none, enter 0.)” A caveat to note is that the survey does not ask who in the household is helping the children with their schoolwork; other people in the household besides parents, like grandparents or older siblings, could be providing help as well. Nonetheless, because household hours are presumably largely provided by parents, we refer to household hours in teaching activities as “parent hours”.11

Finally, in week 6 of the survey (June 4–9), the Census Bureau added a question about children’s learning time independent of their parents to the survey: “During the last 7 days, about how many hours did the student(s) spend doing learning activities on their own? Do not include time spent with teachers or other household members. Enter the total number of hours for all students. (If none, enter 0)”.

Our analysis focuses on the 211,484 survey responses from households that had children enrolled in a K-12 public or private school as of February 2020, and answered questions about how the pandemic had affected how household members received education.12

Specification

The intersection of school system changes and household variables is the focus of our analysis. Our main specification explains PHi, the hours of parents in household i in teaching activities with their children, as a function of a vector of household characteristics, ; a vector of Covid-19 shocks to income, food security, financial distress, and health, ; characteristics of school-provided inputs into children’s education after physical schools closed, ; week- and state-specific fixed effects, wi and fi respectively; and a random error term, ui.

| 1 |

Variables included in follow from basic economics of the household.13 A basic premise of household economics is that household time is scarce and gets allocated across competing ends according to expected returns; in two-parent households, this allocation is done via bargaining, social norms, and/or other means, but as stated above, our study brackets intra-household aspects of time allocation as the Pulse data do not cover it.14 In terms of basic predictions for parental time helping children with their studies, we expect two-parent households to have higher time contributions than single parent households, because their total time endowment is higher.15 In households where the mother works, time spent helping children is expected to be lower than when she does not.16 An increasing number of children is expected to increase the household’s total time helping children, although time per child may fall. As the marginal productivity of parent time helping children is likely to be much higher for younger versus older children, we expect parents’ time to decline as children age.17 While the Pulse Survey does not collect information on children’s ages, it collects the respondent’s date of birth; from this we compute the respondent’s age, which is used as a proxy for ages of children in the household, as older parents presumably tend to have older children as well.18

As mentioned, previous research on parent time helping children with homework shows gradients with respect to parent education and race/ethnicity: better educated parents spend more time helping children with schoolwork than less educated peers, and black and Hispanic parents tend to spend less time than white non-Hispanics.19 However, the radical changes in circumstances caused by the Covid-19 pandemic could potentially flatten or steepen the parental-education gradient. On the “flattening” side, better educated parents who have shifted to work-at-home arrangements have strong incentives to be efficient in spending time helping children with school, to keep up their work responsibilities; their education and/or work experience may also allow them to take less time to shepherd a child through a given assignment, compared to a less educated counterpart.20 Moderate-education and black and Hispanic households may be especially concerned about consequences of disrupted educations on their children’s life outcomes, as some evidence suggests;21 in that case, parents in these groups may place high priority on helping their children continue to learn and may spend more time on it than better-educated peers.22 Similarly, as pandemic-caused job loss has been substantially higher for less- versus more-educated households, and for blacks and Hispanics versus whites (Fairlie et al. 2020), less-advantaged households may have had their time availability increase just as children needed them more. On the “steepening” side, more severe labor-market shocks combined with higher pre-shock economic vulnerability may tilt lower-education parents into financial distress, requiring extra time expenditure to arrange for the households’ basic needs, for example, by visiting food banks.

Variables included in specifically measure whether the labor-market and other shocks of the Covid-19 pandemic affected how much time parents had to help children with schooling. Here we include the Pulse Survey’s measure of whether the household had lost employment income since the start of the pandemic, which could increase the availability of household time to help with children’s learning. For households that were in economically vulnerable positions before the Covid-19 outbreak, parents may be too busy making arrangements to get food or defer rent or car payments to help with schoolwork; thus, our regressions also include measures of food insufficiency and having been late with last month’s mortgage or rent payment. Finally, Covid-19 illness in the household would decrease parents’ ability to help children with schoolwork. While the Pulse Survey does not ask specifically whether people in the household have been ill with the Covid-19 virus, it does ask whether the respondent has missed work due to being sick with Covid-19 or caring for someone who is, which we use as our health shock measure.

The vector of alternative schooling arrangements, , in our main specification is intended to measure possible complementarities and/or substitutabilities between school- and parent-provided inputs into children’s learning. Models of household decisions about allocation of parental time to “child investment” embed a “production function” that explains children’s accumulation of human capital as a function of school-provided inputs, parent time, and other parent-provided resources like computers and access to the internet that facilitate learning (e.g., Heckman and Mosso 2014; Attanasio et al. 2019).23 The marginal productivity of each input is positive but decreasing, but an increase in the level of a given input also increases the marginal productivity of other inputs. This suggests that a precipitous decline in school-provided inputs could substantially reduce parents’ time contributions to children’s education, as each unit of time they provide would produce little learning. But it also leads to the prediction that increased school efforts to continue education via distance learning could increase parent time helping with schoolwork, because complementarity of inputs raises the return to parents’ time.

To investigate these possibilities, we specify the vector, , to include interactions between the school’s modality of delivering education, the availability of live teacher hours, and the household’s digital access. We explore three possible modalities: school is entirely canceled,24 school has shifted to an online-only distance learning format, or school has shifted to distance learning using both online format and distribution of paper schoolwork to children and other mixed modes.25 Potentially the use of paper schoolwork along with online learning could be beneficial to children who have internet or computer access problems, and/or because it increases the scope of learning content relative to the online format only.26 We expect that, for a given mode of delivering distance learning, live teacher hours will increase parental inputs because teacher hours can be expected to increase the marginal product of parent time. Digital access is a dummy variable equal to one if the respondent reports problems with children’s access to technology for educational purposes. Our specification classifies households as having technology access problems if the respondent says children “sometimes,” “rarely,” or “never” have access to the internet for educational purposes (versus “usually” or “always”), or “sometimes,” “rarely,” or “never” have access to a computer or digital device for educational purposes (versus “usually” or “always”).27

To take into account the possibility that marginal productivities of school- and parent-provided inputs could differ by parent education, we estimate the model (1) above for households overall and separately for households at different education levels. For example, school-provided inputs may increase the marginal productivity of parent time by more in lower-and moderate-education households, than in high-education households. This would suggest that the quantity and composition of school-provided inputs could be especially important for enlisting parents’ help and sustaining children’s learning below the top part of the parental education scale.

In the context of the sudden shift to distance learning that took place in Spring 2020, we expect that increased parent hours generally benefited children’s human capital accumulation and was especially required for younger children without reading skills. However, household economics also calls attention to the fact that increased time helping children with school subtracts time from other activities of household adults and, especially in a context where parents may be working at home and/or have trouble finding child care to work outside the home, may overload their days with responsibilities and contribute to stress, fatigue and poor mood.28 Thus, to the extent that schools’ distance-learning arrangements help leverage parents’ time (e.g., by assigning work that children can largely do on their own), parents may be able to reduce their time inputs to no disadvantage to their children’s school progress. Thus, we also use the Pulse data to examine effects of parent time and school-provided inputs on children’s ability to work independently, via the following specification:

| 2 |

Where CHi is children’s hours “doing learning activities on their own” based on a question added to the Pulse Survey in week 6 (June 6–9, 2020). We expect that increased parent and teacher time will increase children’s ability to work independently as prior adult time may increase the marginal productivity of children’s time, enabling them or encouraging them to do more of it.

Descriptive statistics

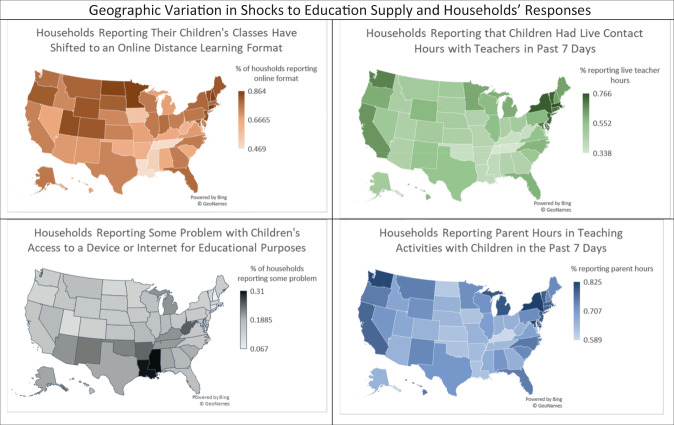

Figure 1 shows some key descriptive statistics from the Pulse data that document considerable geographic variation across the U.S. in the shift to distance learning in Spring 2020. The share of K-12 parents reporting that their children’s schools had shifted to an online distance learning format was highest in the northeast and north central parts of the country; meanwhile, it was below one-half in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee, and between one-half and two-thirds across other south central states.29 Shares of parents reporting that their children had some live contact hours with teachers were again highest in the northeast, as well as in Washington state and California. On the other hand, more than one-quarter of parents said their children “sometimes”, “rarely”, or “never” had access to a computer or the internet for educational purposes in Mississippi, Louisiana, and West Virginia, with access problems also exceeding 20% across the southwest and south central states. Again, the northeastern states stood out as better prepared for the shift to distance learning; in New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Rhode Island, for example, shares of K-12 households that had problems with computer or internet access were below 10%. Shares of parents reporting that someone in the household had spent time in teaching activities with children in the past 7 days were above 75% in a number of states, with New York topping the list at 82.5%. Shares were relatively low in the central part of the country and in West Virginia. Our empirical work explores how intersections of school system changes and households’ situations, including access to technology, affected these variations in parent time inputs into sustaining children’s learning in Spring 2020.

Fig. 1.

Geographic variation in shocks to education supply and households’ responses

Table 1 presents basic descriptive statistics on Covid19 shocks from the Pulse data, showing differences across households by the educational attainment of the parent who responded to the survey. Covid-19 shocks were experienced across all education groups, although clearly affecting less educated households more severely than the better educated. Some 55.9% of households with K-12 children reported that someone in the household had lost employment income since March 13, 2020 (which presumably includes hours reductions and unpaid leaves as well as job loss). The share was 23.3 percentage points higher for households where the respondent had less than a high school degree than it was for households where that person had a 4-year college degree, but even in the college-educated category the share was 42.7%. Among households in the below high school category, 25.3% reported not having enough food at least some days in the past week, versus 3.6% in the college-educated group. About one-quarter of households in the below high school group had been late with the previous month’s rent or mortgage payment, versus 8.5% of the college-educated group. About 2% of respondents in the below high school group were away from work due to Covid-19 illness (including taking care of someone else), versus 0.3% in the college-educated group; with the large number of observations in the data, this difference is statistically significant, as are the other differences across groups. Thus, the Pulse data show that, among households with K-12 children, less educated households faced substantial differential hardships from the pandemic, on top of the expectation for all parents of stepping up to help their children continue to learn.

Table 1.

Shares of households reporting Covid19 shocks

| All HHs w/K-12 children | By educational attainment of survey respondent | Difference between HHs where R has <High school versus 4-year college degree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <High school | HS or GED | Some college or AA | 4-year college degree | Difference | p-value | ||

| Lost employment income | 0.559 | 0.661 | 0.621 | 0.594 | 0.427 | 0.233a | 0.000 |

| Food insufficiency | 0.134 | 0.253 | 0.198 | 0.130 | 0.036 | 0.217a | 0.000 |

| Late paying rent or mortgage last month | 0.170 | 0.240 | 0.209 | 0.193 | 0.085 | 0.154a | 0.000 |

| Not working due to Covid illness (self or caring for someone else) | 0.011 | 0.021 | 0.020 | 0.009 | 0.003 | 0.018a | 0.000 |

| Number of observations | 211,484 | 5686 | 24,057 | 67,904 | 113,837 | ||

| Share of households (weighted) | 1.000 | 0.103 | 0.393 | 0.308 | 0.299 | ||

All descriptive statistics are computed using sample weights. See appendix for detailed variable definitions

aStatistically significant at 1% level

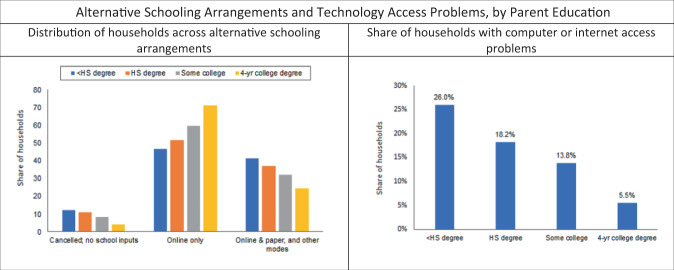

Figure 2 documents basic descriptive statistics on school system changes and households’ access to technology, which again show some clear gradients with respect to parental education. Shares of parents saying their children’s school was canceled entirely, with no shift to online delivery and no live contact with teachers via phone or internet, was 11–12% in households where the respondent had a high school degree or less, versus 4.2% of the college-educated group.30 Some 71.2% of respondents in the college-educated group said their children’s schools had shifted to online-only platforms (i.e., without also distributing schoolwork on paper), versus 47–52% of households with a high school degree or less. In the latter groups, online and paper and other mixed modes of delivery were significantly more common. As discussed below, use of paper packets as well as the internet may be valuable for delivering content to households without internet access and/or enriching learning content for households that have it. In this respect, the Pulse data show (as expected) that the problems with access to computers and the internet are more prevalent for less educated households. In the group with less than a high school degree, 26% report problems with regular access to a computer or the internet. In the college-educated group, this share was 5.5%.

Fig. 2.

Alternative schooling arrangements and technology access problems, by parent education

Figure 3 shows that, unlike distance-learning arrangements and access to technology, parental time inputs and live contact hours with teachers did not have clear gradients with respect to parent education. This finding is important given expectations based on pre-pandemic differentials that children from less-advantaged households may get relatively low levels of help from parents and/or teachers during the pandemic; instead, the data show parents and teachers contributing time similarly across household groups.31 Overall 72.2% of respondents said that some household member had spent time in the past week in teaching activities with children; the share was 71.6% in households where the respondent did not have a high school degree, versus 73.5% where the respondent had a 4-year college degree, which was an insignificant difference. Among households reporting positive parent hours, the average number was actually somewhat higher for respondents with a high school degree only (13.4 h) than it was for the college educated group (12.9 h). Overall, 54.7% of parents said their children had live contact hours with teachers in the past 7 days; shares reported by the below high school and college-educated households were virtually the same. Among households reporting positive teacher hours, the average number actually fell somewhat with parental education, e.g., it was 6.7 h in the below-high school group, versus 5.7 h for the college-educated group. Finally, in terms of time spent by children in independent learning activities (collected in weeks 6–10 of the survey only), 61% of households reported children spending some time in learning activities on their own in the past 7 days; surprisingly, this share was higher in the below high school group than it was in the college educated group (67.8% versus 61.8%), and the average number of hours did not differ significantly. Thus, the data show an unexpected pattern that, although less educated households were more likely to have schools canceled, and had significantly higher problems with computer and internet access, their school systems were providing similar levels of live teacher hours and parents provided no less time to helping children learn than the college-educated group.

Fig. 3.

Household and school time inputs, by parent education

Results

Table 2 shows our main results on predictors of parents’ time inputs.32 The first column shows predictors of the probability that someone in the household spent time with children in teaching activities in the previous week, estimated via a linear probability model, while the second column gives the predictors of the number of parent hours estimated via a Tobit model. The latter takes into account that hours cannot be below zero and in the Pulse data are top-coded at 48 h.

Table 2.

Predictors of parent hours helping children with schoolwork

| Probability that parent has positive hours | Number of parent hours | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | s.e. | Coeff. | s.e. | |

| Household and respondent characteristics | ||||

| Household type (married couple omitted) | ||||

| Single female | −0.006 | 0.007 | −0.701b | 0.348 |

| Single male | −0.030a | 0.008 | −0.999 | 0.626 |

| Number of children <18 | 0.017a | 0.002 | 1.251a | 0.099 |

| R age | −0.003a | 0.000 | −0.097a | 0.011 |

| R is working female | −0.039a | 0.004 | −1.489a | 0.178 |

| Respondent education (<HS degree omitted) | ||||

| HS degree or GED | 0.011 | 0.015 | 1.071b | 0.448 |

| Some college or AA degree | 0.034a | 0.012 | 1.830a | 0.465 |

| 4-year college | 0.057a | 0.012 | 2.243a | 0.427 |

| R race/ethnicity (white non-Hispanic omitted) | ||||

| Black non-Hispanic | 0.061a | 0.011 | 1.747a | 0.322 |

| Hispanic | 0.018a | 0.007 | −0.130 | 0.362 |

| Asian | −0.001 | 0.008 | −0.644c | 0.340 |

| Other | 0.028b | 0.014 | 1.021a | 0.393 |

| Covid-19 Shocks | ||||

| Lost employment income | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.714a | 0.208 |

| Food insufficiency | 0.038a | 0.005 | 1.982a | 0.199 |

| Rent or mortgage late last month | 0.011 | 0.008 | 0.167 | 0.277 |

| Not at work due to Covid-19 illness | −0.055a | 0.020 | 0.600 | 1.343 |

| R-reported school delivery mode(s), live teacher hours, and adequacy of HH technology access (canceled entirely is omitted) | ||||

| Online only with: | ||||

| No teacher hours, some tech access problems | 0.014 | 0.016 | 0.349 | 0.429 |

| No teacher hours, no tech access problems | −0.051a | 0.013 | −1.869a | 0.368 |

| Live teacher hours, some tech access problems | 0.344a | 0.013 | 8.678a | 0.546 |

| Live teacher hours, no tech access problems | 0.316a | 0.013 | 8.294a | 0.446 |

| Online & paper and other modes with: | ||||

| No teacher hours, some tech access problems | 0.025 | 0.017 | 0.555 | 0.592 |

| No teacher hours, no tech access problems | 0.043a | 0.016 | 1.083a | 0.397 |

| Live teacher hours, some tech access problems | 0.321a | 0.014 | 7.265a | 0.566 |

| Live teacher hours, no tech access problems | 0.351a | 0.013 | 8.716a | 0.375 |

| State and week fixed effects | Yes | Yes | ||

| Adjusted R2 or pseudo-R2 | 0.279 | 0.038 | ||

| Number of observations | 199,014 | 199,014 | ||

All regressions are run using sample weights. Standard errors are clustered at the state level.

aStatistically significant at 1% level

bStatistically significant at 5% level

cStatistically significant at 10% level

The data show that, as expected, basic household characteristics play significant roles in determining parent time spent with children on teaching activities. Single parents spent less time helping children than married-couple households, consistent with having a lower time endowment. Specifically, we find that, controlling for other factors, single male parents were less likely to report having spent time helping children in the past week, while single-female parents spent about 45 min less per week.33 Respondents who were working mothers were less likely to report that household members had helped children in the past week, and reported 1.5 fewer hours of help in the previous week, compared to respondents who were men (working or not) or women who were not working. An increasing number of children increased the probability of having provided help and number of hours spent.34 As mentioned above, the Pulse survey did not collect information on children’s ages, so we include the parent’s age as a proxy, expecting that older parents will have older children who are less likely to need the same kind of help managing schoolwork as younger children. We find that, indeed, increased parent age is associated with decreased time helping children, other things being equal.35

Results show that, after controlling for household characteristics, Covid-19 shocks, and school-system characteristics, parental time helping children was positively associated with parental education. Differences relating to the probability of spending time helping children were not large: other things being equal, households where the respondent had a 4-year college degree were 5.7 percentage points more likely to have spent time helping children in the past week than households where the respondent did not have a high school degree. Households with a high school degree spent 1 h more per week helping children compared to households in the below high-school group; for households with some college education but no 4-year degree, the difference was 1.8 h while for the college-educated group it was 2.2 h.

In terms of race and ethnicity, the Pulse data show that, controlling for other factors, households where the respondent was black and non-Hispanic spent significantly more time helping children than households with white non-Hispanic respondents: they were 6.1 percentage points more likely to have reported spending time helping children in the previous week than white non-Hispanic respondents, with the time spent 1.7 h higher. Hispanic respondents were also more likely to have reported helping children with learning, while Asian respondents reported spending about half an hour less than white non-Hispanic respondents (the latter result is statistically significant at a 10% level only). The findings for black non-Hispanic and Hispanic households differ from some previous research finding parental time to be lower for these groups than for white non-Hispanic counterparts.36 Possible reasons could include greater concerns about children falling behind,37 and/or types of school-provided inputs that could require more parental help; however, other studies in the literature also find no differences between black and Hispanic parents versus white non-Hispanic parents in the amount of help they provide, or find parents in the former group providing more help than those in the latter, as we do.38

Turning to COVID related shocks, we find that households that lost employment income since the beginning of the pandemic spent three-quarters of an hour more helping children in the previous week than households that had not. This is consistent with COVID-related job loss increasing parents’ time availability at a time when they were suddenly expected to step in and help children shift to distance learning. Households experiencing food insufficiency were also more likely to have spent time helping children; this is contrary to our expectation that parents in households that needed to make extra efforts to meet basic needs would have less time available for helping children, but may reflect extra effects of job loss (versus income loss) on both food sufficiency and parents’ time availability.

With respect to the type of alternative schooling that households faced, Table 2 clearly shows that, if the school system went online only and provided no live teaching hours and the household had no computer or internet access problems, parents actually spent less time helping children than if school was canceled entirely: they were 5.1 percentage points less likely to have spent time in teaching activities in the past week, and spent 1.9 fewer hours, than they did in households where school was canceled entirely. Households with technology problems and no live teacher hours spent the same amount of time helping children as households that had school canceled entirely, whether their school was online only or some combination of online and paper delivery.

Having live teacher hours had clear, large positive effects on parent time, whether the household had technology problems or not and whether their school was online only or a combination of online and paper delivery. Thus, compared to parents in households where school was canceled entirely, parents in households that had live teacher hours and online-only systems were 34.4 percentage points more likely to have helped children in the past week if they had technology problems and 31.6 percentage points more likely if they did not; if the system combined online and paper delivery, parents were 32.1 percentage points more likely to have helped if they had technology problems and 35.1 percentage points more likely if they did not. Numbers of parent hours were also much higher when there were live teacher hours than when there were not: for example, in a household that had combined online/paper delivery and no technology access problems, parents spent one hour more per week helping children if their children had no live teacher hours, versus 8.7 h more if they did. This suggests complementarity between teacher hours and parent hours: a shift from no teacher hours to positive hours substantially increases parental time helping children, presumably because marginal returns to parent time are higher when teachers motivate, explain and check children’s schoolwork.39

The results show some notable differences relating to technology access problems, and to systems that are online only versus online with paper options. In systems that are online only and have live teacher hours, parents were more likely to have spent time helping children and to have spent more hours if the household had technology access problems than if it did not. This shows that, while increased parent time in the pandemic may have been generally beneficial for children, as it substituted for the substantial reduction in school-provided inputs, issues of the efficiency also explain differences in parent time inputs. The result here suggests that parents less able to rely on computers and the internet to help with learning had to spend more time helping children than parents in better-equipped households, which was likely an extra hardship.

Finally, the results show that in households that had live teacher hours and no technology access problems, having a combined online/paper system was associated with higher parent time than an online-only mode. This finding is potentially consistent with emerging research that shows “blended” online learning systems—which combine online learning with face-to-face classes and a mix of online and traditional offline assignments—tend to be more effective in promoting learning than systems that are online only (Escueta et al. 2017).40

Table 3 examines differences in parents’ time inputs by parental education. Several of the findings with respect to household and respondent characteristics show up across education groups: for example, increased parent age was associated with decreased parental time inputs in all education groups. With respect to race and ethnicity, the positive finding for black non-Hispanic respondents from Table 2 appears for households that have a high school degree or more (who spent two hours more per week than white non-Hispanic counterparts), but not for those with less than a high-school degree. In the below high school group, Hispanic respondents reported spending four hours less per week helping children than white non-Hispanic counterparts, possibly reflecting language barriers to providing help.41 With respect to Covid-19 shocks, we see that increases in parental time related to losses in employment income increased parent hours for households with a high school degree or some college but not a 4-year degree, but not for those with less than a high school degree or those with a 4-year college degree.

Table 3.

Effects of school delivery mode(s), teacher hours, and adequacy of HH technology access on parent hours, by respondent education

| Number of parent hours | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Below HS | HS degree | Some college | College | |||||

| coeff | s.e. | coeff | s.e. | coeff | s.e. | coeff | s.e. | |

| Household and respondent characteristics | ||||||||

| Household type (married couple omitted) | ||||||||

| Single female | −2.32a | 0.73 | −0.95c | 0.56 | −0.34 | 0.45 | −0.01 | 0.43 |

| Single male | −1.91 | 1.23 | −0.80 | 1.08 | −1.35c | 0.71 | −1.41c | 0.75 |

| Number of children <18 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 1.14a | 0.32 | 1.45a | 0.12 | 1.83a | 0.11 |

| R age | −0.07b | 0.03 | −0.13a | 0.03 | −0.07a | 0.02 | −0.09a | 0.02 |

| R is working female | 0.35 | 0.69 | −0.99c | 0.52 | −2.02a | 0.47 | −1.69a | 0.21 |

| R race/ethnicity (white non-Hispanic omitted) | ||||||||

| Black non-Hispanic | −1.75 | 1.22 | 2.09a | 0.72 | 1.94a | 0.63 | 2.04a | 0.34 |

| Hispanic | −3.97a | 0.95 | 0.50 | 0.68 | −0.45 | 0.42 | 0.85 | 0.55 |

| Asian | −5.43a | 1.34 | −0.91 | 0.99 | −1.98a | 0.50 | 0.42 | 0.63 |

| Other | −1.81 | 3.11 | −0.12 | 1.39 | 1.52b | 0.59 | 1.71a | 0.45 |

| Covid-19 Shocks | ||||||||

| Lost employment income | 1.53 | 1.00 | 1.38b | 0.56 | 0.50b | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.26 |

| Food insufficiency | 0.79 | 0.82 | 2.09a | 0.51 | 1.90a | 0.30 | 2.08a | 0.22 |

| Rent or mortgage late last month | 1.19 | 1.05 | −0.19 | 0.53 | 0.38 | 0.41 | 0.28 | 0.31 |

| Not at work due to Covid-19 illness | −4.17b | 2.07 | 2.53 | 2.21 | 0.40 | 1.22 | −0.52 | 1.60 |

| R-reported school delivery mode(s), live teacher hours, and adequacy of HH technology access (canceled entirely is omitted) | ||||||||

| Online only with: | ||||||||

| No teacher hours, some tech access problems | 2.84 | 1.80 | 1.44 | 0.96 | −0.37 | 0.86 | −2.32a | 0.85 |

| No teacher hours, no tech access problems | −0.85 | 1.58 | −0.89 | 1.02 | −2.16a | 0.55 | −3.71a | 0.48 |

| Live teacher hours, some tech access problems | 11.72a | 2.16 | 8.35a | 1.39 | 7.69a | 0.69 | 8.05a | 0.65 |

| Live teacher hours, no tech access problems | 10.84a | 1.96 | 8.51a | 0.80 | 7.61a | 0.64 | 6.60a | 0.48 |

| Online & paper and other modes with: | ||||||||

| No teacher hours, some tech access problems | 1.20 | 1.71 | −0.57 | 1.43 | 1.90a | 0.61 | −0.63 | 0.88 |

| No teacher hours, no tech access problems | 3.97b | 1.87 | 2.12c | 1.12 | 0.82c | 0.48 | −1.64a | 0.61 |

| Live teacher hours, some tech access problems | 9.67a | 1.44 | 6.94a | 1.30 | 6.48a | 0.65 | 6.90a | 0.72 |

| Live teacher hours, no tech access problems | 10.52a | 1.35 | 8.38a | 0.91 | 8.39a | 0.55 | 7.52a | 0.49 |

| State and week fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.032 | 0.037 | 0.038 | 0.048 | ||||

| Number of observations | 4998 | 22,030 | 63,522 | 108,464 | ||||

All regressions are run using sample weights. Standard errors are clustered at the state level

aStatistically significant at 1% level

bStatistically significant at 5% level

cStatistically significant at 10% level

With respect to school-system inputs, the results show that live teacher hours increased parent hours significantly across all parent-education groups, with the magnitude of the effect especially large for households with less education. Thus, for example, a shift from canceled entirely to an online-only system with some live teacher hours and no technology access problems increased parent hours by 10.8 h per week in households if the respondent had less than a high school education, versus 6.6 h per week in the college-educated group, other things being equal. This suggests that live teacher hours were especially important for enlisting parent help in less-educated households, where the extra guidance from and engagement with a teacher may have been especially beneficial for helping parents see how they could best help.

Finally, Table 4 shows predictors of children’s time working alone on learning activities. Here household and respondent characteristics have few statistically significant effects, although parent age increases children’s independent learning time (consistent with older parents having older children who are expected to be able to work on their own) and Black non-Hispanic, Hispanic, and Asian respondents all reported children in their households spending more time working alone than white non-Hispanic respondents. However, children’s independent hours were significantly affected by hours that were spent with them by teachers and parents. In households that had online learning systems (with or without paper options) but no time spent with them by teachers or parents, children were more than 30 percentage points less likely to have spent any time learning on their own in the previous week than children in otherwise similar households for which school was canceled entirely (but parents may have spent time helping children learn).42 Thus, having schools put material online, without combining materials with parental and/or teacher time inputs, appears to discourage children from learning on their own, relative to having no school at all. To be sure, the share of households reporting no parent, teacher, or student hours rose in the second half of June as school years ended. But even in the first half of June (when schools were mostly still in session), independent student hours were lowest in households reporting online school only and no parent or teacher hours. This is consistent with students working minimally without adult support and/or parents and students bailing out of schoolwork when the school posts work online without live teacher-contact hours.

Table 4.

Effects of school delivery mode(s), teacher hours, and parent hours on children’s independent learning time

| Probability that children have independent learning time | Number of independent learning hours | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| coeff | s.e. | coeff | s.e. | |

| Household and respondent characteristics | ||||

| Household type (married couple omitted) | ||||

| Single female | −0.005 | 0.008 | −0.110 | 0.163 |

| Single male | −0.004 | 0.015 | 0.236 | 0.358 |

| Number of children <18 | −0.004 | 0.004 | 0.196a | 0.071 |

| R age | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.026a | 0.007 |

| R is working female | −0.003 | 0.005 | −0.267c | 0.162 |

| Respondent education (<HS degree omitted) | ||||

| HS degree or GED | −0.016 | 0.010 | −0.060 | 0.438 |

| Some college or AA degree | 0.001 | 0.011 | 0.448 | 0.290 |

| 4-year college | 0.013 | 0.010 | 0.529c | 0.313 |

| R race/ethnicity (white non-Hispanic omitted) | ||||

| Black non-Hispanic | 0.046a | 0.011 | 0.933a | 0.252 |

| Hispanic | 0.038a | 0.008 | 0.300c | 0.175 |

| Asian | 0.042a | 0.011 | 1.183a | 0.289 |

| Other | 0.027b | 0.013 | 0.429 | 0.339 |

| Covid-19 Shocks | ||||

| Lost employment income | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.237 | 0.160 |

| Food insufficiency | −0.007 | 0.004 | 0.273 | 0.261 |

| Rent or mortgage late last month | 0.002 | 0.006 | −0.028 | 0.208 |

| Not at work due to Covid-19 illness | −0.013 | 0.024 | −0.394 | 0.535 |

| R-reported school delivery mode(s), live teacher hours, and parent hours; tech access (canceled entirely is omitted) | ||||

| Online | ||||

| No teacher or parent hours | −0.314a | 0.012 | −3.258a | 0.221 |

| Parent hours, no teacher hours | 0.413a | 0.012 | 3.066a | 0.227 |

| Teacher hours, no parent hours | 0.298a | 0.021 | 2.016a | 0.499 |

| Both teacher and parent hours | 0.485a | 0.014 | 5.757a | 0.237 |

| Online and paper with: | ||||

| No teacher or parent hours | −0.330a | 0.014 | −3.434a | 0.181 |

| Parent hours, no teacher hours | 0.397a | 0.017 | 3.075a | 0.256 |

| Teacher hours, no parent hours | 0.083b | 0.039 | −0.771 | 0.667 |

| Both teacher and parent hours | 0.494a | 0.011 | 4.951a | 0.452 |

| Technology access problems | −0.025a | 0.009 | −0.327 | 0.207 |

| State and week fixed effects | Yes | Yes | ||

| Adjusted R2 or pseudo-R2 | 0.563 | 0.034 | ||

| Number of observations | 96,668 | 96,668 | ||

All regressions are run using sample weights. Standard errors are clustered at the state level.

a Statistically significant at 1% level

b Statistically significant at 5% level

c Statistically significant at 10% level

Whether schooling was offered online-only or online with paper options, children were about 40 percentage points more likely to have worked on their own in the past week if a parent had worked with them and 49–50 percentage points more likely to have worked on their own if both a parent and a teacher had. In contrast, teacher hours without parent hours increased the probability of children working on their own by 29.8 percentage points if their schooling was online only or 8.3 percentage points if it combined online and paper options, relative to the situation where school was entirely canceled. These findings are consistent with parents playing a key “managerial” role in helping children work effectively on their own; while both parent and teacher time increase children’s time working alone, the larger effect of parent time suggests they have better information and insights into motivating and managing their own children’s learning from the home setting. Finally, we find that problems accessing the computer or internet reduced children’s probability of having worked independently on their own, although the effect was not large: other things being equal, children in households that had computer or internet access problems were 2.5 percentage points less likely to have worked on their own in the previous week, compared to children in households without access problems.

Discussion and conclusions

In summary, our analysis shows parental time helping children learn in the Covid-19 pandemic varied with household characteristics, other Covid-19 shocks, and school-provided inputs. Consistent with basic predictions from household economics, single-parent households and households where the mother worked spent less time helping children, in line with their lower time availability; parent time increased with the number of children; and older parents spent less time working with children, consistent with older children being better able (and/or expected) to work on their own. We also find that households that had lost employment income due to Covid-19 reported more hours helping children, suggesting that job losses may have had the benefit of freeing up parent time exactly when schools expected them to help children transition to distance learning. While the Pulse data show problems accessing computers and the internet for educational purposes to be concentrated in households with less educated parents, our results also show access problems to have increased parent time helping children, suggesting that parents tried to work around digital access problems but had to spend more timing help children with given projects when they lacked digital access. Thus, school policies that give students access to technology, such as laptop or tablet loaner programs, can free up time for parents for other productive uses.

A key result of our work is that parents and children allocated more time to educational activities at home when their school systems provided more inputs as well. When schools initially closed, younger children needed immediate parental help setting up online accounts and learning to use new systems. But the Pulse data show parents to have continued spending time in teaching activities with children from April through the end of the school year. While we have no direct measure of student outcomes or the effectiveness and efficiency of this time use, past research sheds light on potential implications of our results. In terms of parental inputs, many studies show parental inputs into children’s schooling lead to increases in student performance (Fehrmann et al. 1987; Jeynes 2003, 2005; Sanders 1998; Smith and Hausafus 1998; Thorlindsson et al. 2007; Cabus and Ariës 2017).43 While the education literature points out that certain types of parental help may matter more in improving children’s school performance than parental help per se (Patall et al. 2008), parental help in the Covid-19 pandemic differed from parental help in normal times in that, at least for younger children, it was a necessary input for continued learning rather than a potentially valuable but optional complementary input.

Our results show that live teacher hours increased parent hours significantly across all parent-education groups, suggesting that extra guidance from and engagement with a teacher helps parents see how they can best help their children learn. Live teacher hours appear to make a difference in parental engagement, which could provide support to parental involvement policies in effect in numerous school districts (Kessler-Sklar and Baker 2000, Marschall and Shah 2020).

Nonetheless, it may be a fruitful area of future research to investigate the productivity of parents’ time contributions to children’s learning, and the extent to which they complemented or substituted for the dramatically different school system inputs after schools closed. In other words, even with high levels of parent and teacher hours, there are considerable uncertainties about whether stop-gap home-based learning systems could really begin to substitute for what normally happens in school. In addition, from a social welfare perspective, it is not entirely clear that more parent time on schooling is necessarily good overall. While it is almost certainly better for students, increased parental time could come at the cost of parental employment or income (which may offset some of the benefits to child learning.)

Our results also suggest an importance of distance-learning modality and its interplay with parental inputs. In instances where schools offered both online and paper inputs, rather than online only, parents spent more time working with children and children spent more time working independently. Why are parents and children putting in more time when learning resources were diversified? By giving families alternatives, offering paper packets and other resources may help bridge the gap for those who have limited access to technology (Stein et al. 2020). There may be other families, however, that actively use both types of school delivery systems, and paper can be a complement to online learning. For this latter group, the mixed modality may provide an enrichment opportunity and valuable exercises in handwriting, notetaking, problem solving by hand and also reading in print. For example, studies have found that taking notes uses different cognitive processes and that students have higher comprehension after taking notes (Faber et al. 2000; Makany et al. 2009). To the extent that increased household time reflects increased interest and engagement in learning, our finding is potentially consistent with the view that “blended” systems may promote more learning than systems that are online only (Escueta et al. 2017). This is another modality that policymakers could test going forward—using both online and paper materials—as many U.S. public schools have adopted hybrid learning where students alternate between in-person and remote days.

Finally, our results show broad-based contributions of parent time to children’s learning with respect to parent education and race/ethnicity. This is contrary to expectations that better-educated parents would spend more time helping children learn and that less-educated households would be frozen out of distance learning due to computer and internet access problems. Some of our results show gradients by parent education, but they are generally small. Our findings with respect to race and ethnicity, based on nationally representative samples of 200,000 households, show black non-Hispanic and Hispanic households having higher likelihoods of spending time helping children learn over the course of a given week than otherwise equivalent white non-Hispanic counterparts. As mentioned, the research literature suggests that ‘returns’ to parent time in terms of improving children’s outcomes may increase with the parent’s education,44 so that relatively flat gradients in parent time may not spell equally effective mitigation of loss of school-provided inputs in the sudden shift to distance learning. Nonetheless, the broad-based contributions of household time found in our analysis show parents across the educational spectrum to have been strongly concerned with doing what they could to minimize these losses.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank three anonymous referees and Shoshana Grossbard for comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this work and William Rost for discussion. Jeffrey Yaun provided valuable research assistance.

Appendix A. Variable definitions

| Household and respondent characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Household type: | |

| Married couple | Respondent is married (omitted) |

| Single female | Respondent is female and not married |

| Single male | Respondent is male and not married |

| Number of children <18 | Number of people under 18 years old currently living in the household |

| R age | 2020 minus respondent’s year of birth |

| R is working female | Respondent is female and did work for pay or profit in the last 7 days |

| Respondent education: | R’s educational attainment is: |

| Below HS | Less than high school or some high school (omitted) |

| HS degree or GED | High school graduate or equivalent (e.g., GED) |

| Some college or AA degree | Some college but degree not received or in progress, or Associates degree |

| 4-year college | Bachelors’ degree or graduate degree |

| R race/ethnicity: | R self identifies as: |

| White non-Hispanic | White alone, not of Hispanic origin (omitted) |

| Black non-Hispanic | Black alone, not of Hispanic origin |

| Hispanic | Of Hispanic origin |

| Asian | Asian alone, not of Hispanic origin |

| Other | Other race (American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, Samoan, other Pacific Islander) or more than one race, not of Hispanic origin |

| Other Covid-19 household shocks: | |

| Lost employment income | Someone in the household experienced a loss of employment income since March 13, 2020 |

| Food insufficiency | R says in the past 7 days, the household’s amount of food was “sometimes” or “often insufficient” |

| Rent/mortgage late last month | Last month’s rent or mortgage was not paid on time |

| Not at work due to Covid-19 illness | R was not at work in the past 7 days due to being sick with Covid-19 or caring for someone who was |

| Education measures | |

| School delivery mode: | R indicates that Covid-19 affected how children in the HH get education as follows: |

| Canceled | school was canceled; no distance learning via internet, schoolwork distributed on paper, or some other means; and no live teacher hours |

| Online only | distance learning took place online |

| Online+paper or other | distance learning took place online and on paper, online and via other means, or via paper or other means only |

| Technology access problems | R says that either a computer or the internet, or both, is sometimes, rarely or never available for children’s educational purposes (versus usually or always) |

| Teachers hours | Number of hours the student had live contact with a teacher by video or phone in the past 7 days |

| Parent hours | Number of hours spent by all household members on all teaching activities with children in the household in the past 7 days |

| Children’s independent learning hours | Number of hours that student(s) spent doing learning activities on their own in the past 7 days, excluding time spent with teachers or other household members |

| Time and geography | (Results not shown) |

| Week | =1 for survey weeks 1–10; 0 otherwise |

| Major metropolitan area | =1 if R lives in one of 15 major metropolitan areas; 0 otherwise |

| State | =1 if respondent lives in given state; 0 otherwise |

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

See Bacher-Hicks et al. (2020) and Education Week (2020a, b). Between March 16 and March 23, 2020, 39 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico issued state-wide school closures, which remained in effect for the rest of the school year. Montana and Wyoming issued state-wide school closure orders on March 16 but allowed them to expire in May; after that local school districts could decide whether to reopen. Between March 16 and March 24, 7 states (California, Florida, Idaho, Kentucky, Maine, South Dakota, and Tennessee) recommended state-wide school closures; most states later closed schools state-wide for the rest of the school year Education Week (2020a, b).

E.g., Porterfield and Winkler (2007), Guryan et al. (2008), Wight et al. (2009), and Dotti et al. (2016).

See references in previous footnote as well as Ramey and Ramey (2010), Heckman and Mosso (2014), and Mencarini et al. (2019).

See Fields et al. (2020) for a full description of the survey sample, methodology, and questionnaire.

The MAF contains cell phone/address pairs for over 88% of U.S. residential addresses and email/address links for almost 80% of addresses in the country.

Newly sampled households are contacted by email and text if both are available, by email if no cellphone number is available, and by text if no email is available. The survey can be answered in English or Spanish. Fields et al. (2020).

All analyses in this paper use the sample weights.

Thus, for example, it is not possible to examine “added worker” effects using the Pulse data. See, for example, Lundberg (1985), Starr (2014), Ayhan (2018), and Bredtmann et al. (2018).

As the share of respondents with K-12 children reporting no change in their children’s school is extremely small (less than one-half of one percent), and their circumstances must be unusual in ways we cannot identify, we exclude these cases from our analysis.

To reduce the possibility that respondent characteristics like age and education pertain to adult household members other than parents of the K-12 enrollees (such as young adult children or older relatives), the analysis excludes 6209 survey responses where the respondent’s age was under 26 and 4823 cases where the respondent’s age was over 65 if the household contained more adults than implied by the respondent’s marital status (i.e., more than two adults if the respondent was married or more than one if single). Note that the Pulse Survey records all people within the household age 18 or older as “adults,” which could include high school seniors and children attending college. To explore whether non-parent adult household members play a role in helping K-12 children with schoolwork, we ran alternative versions of our main regression specifications (Tables 2 and 3) including a dummy variable to indicate whether the household included non-parent adults. Results showed that reported time spent helping children learn was significantly lower in such households, compared to otherwise similar households without non-parent adults. While the explanation for that finding is not clear, it suggests that non-parent adults do not generally add to household time helping K-12 children learn.

The analysis excludes 3495 households that had children in K-12 home schooling only.

Lundberg and Pollak (2007), Browning et al. (2014). See Appendix Table 1 for detailed variable definitions.

E.g., Guryan et al. (2008), Roman and Cortina (2016), and Chiappori and Mazzocco (2017). In early evidence on the Covid-19 pandemic, Adams-Prassl et al. (2020) found that both women and men in the U.S. and U.K. who reported that they were working at home spent around 2 h per day helping children with schooling in April 2020, with somewhat more time by women; in Germany women spent almost 3 h compared to men’s hours below 2. See also Carlson et al. (2020) and Farré et al. (2020).

Gurayan et al. (2008).

e.g. Mencarini et al. (2019).

Adams-Prassl et al. (2020) find evidence of this for the U.S., U.K., and Germany.

See also Adams-Prassl, et al. (2020), Table B6.

As Gurayan et al. (2008:32–33) discuss, there are income and substitution effects related to parent income. Higher-wage parents have relatively high incentive to allocate time to paid work rather than “home-production” activities like helping children with schoolwork (a substitution effect), but their higher incomes also increase their demand for home-produced goods (which could include better-educated children) (an income effect).

Thus, for example, a Gallup poll in March 2020 found 52% of non-white parents saying they were moderately to very concerned that “the coronavirus situation will have a negative impact on [their] child’s education,” versus 36% of white parents (Brenen 2020).

Using internet search data, Bacher-Hicks et al. (2020) found that, in April 2020, people in higher-income zip codes undertook many more internet searches for educational resources than people elsewhere, suggesting more substitution of home inputs for school inputs in higher-income areas.

Gould et al. (2020), Del Boca et al. (2013), Guryan et al. (2008), Ramey and Ramey (2010), Plug and Vijverberg (2003) and Yum (2016). See Haveman and Wolfe (1995), Black et al. (2005), and Holmlund et al. (2011) for literature reviews of intergenerational transfers.

Households classified as having school “entirely canceled” said that school was canceled and reported no mode for delivering distance learning nor live teacher hours. Households that said school was canceled and reported no alternative model but reported positive live teacher hours were classified in the “other” category.

The “online and paper” category includes respondents reporting “other” modes (where survey respondents were asked to specify the mode, but the information is not publicly available), “other” and paper, “other” alone, paper alone, as well as people reporting no mode but also reporting live contact hours with teachers.

Stein et al. (2020).

It is potentially a concern that households with technology-access problems could be underrepresented in a digitally administered survey.

Responses are pooled over survey weeks. As noted, the Pulse questionnaire asked, “How has the coronavirus pandemic affected how the children in this household received education?”; because the first survey week was in April, four to five weeks after schools were initially closed, the data do not capture geographic variation in how quickly school systems were able to get alternative delivery systems in place.

Note that, although questions about hours spent by parents, teachers and children in learning activities ask specifically about the last 7 days, questions about alternative schooling arrangements asked generally about how the coronavirus pandemic affected how children in the household received education (i.e., with no reference period specified).

E.g. Torpey (2019).

The regression analyses are confined to observations with non-missing values for the variables included in the model.

Note that the information collected in the Pulse survey does not allow us to identify parent couples who are not married.

It is also possible that older children helped younger children with schoolwork, which could contribute to the positive effect. Not surprisingly, as the number of children rises, the household’s average number of helping hours per child declines, consistent with parents having to spread themselves thinner when there are more children in the house. As the average number of children per household declines with the parent’s education, average parent hours per child are somewhat higher in households with more versus less educated parents: parents average 4.9 h per child per week in households where the parent has less than a high school degree versus 5.6 h per child per week where the parent has a 4-year college degree.

As an alternative, we also split the sample into “older” and “younger” parents (using 40 and 45 as alternative cutoffs), to explore whether effects of school-system and other variables may have been more important for parents of younger children, who clearly needed parental help transitioning to distance learning and managing schoolwork. Results for the two groups were qualitatively similar, although, as expected, some of the effects were quantitatively larger in the young- versus older-parent group, indicating that parents of young children spent more time on children’s schoolwork.

E.g. Ramey (2011), citing data from the American Time Use Survey.

Horowitz (2020).

Hoover-Dempsey et al. (2001), Hill et al. (2004), Lee and Bowen (2006), Jackson and Remillard (2005), National Center for Education Statistics (2019, Table 227.40).

Billman et al. (2005), Dalhouse and Dalhouse (2009). Takeuchi et al. (2019), Sethi and Scales (2020).

Although not shown in the table, estimated fixed-effects by week show that shares of parents spending time helping children learn and the hours spent declined after mid-June, as school years ended. But even in late June and early July (survey weeks 9 and 10), 49.5% of parents reported helping children in learning activities in the previous week, down from 89.3% in late April and early May (survey weeks 1 and 2).

Note that, while Pulse Survey respondents can answer the survey in Spanish, the publicly available data do not indicate whether they did.

In households reporting that school was online only and neither a parent nor a teacher had helped children with learning activities in the past 7 days, 13.4% reported some independent student hours in the previous week. In households reporting that school was canceled entirely, 52.7% of parents said they had spent some time helping children with learning activities in the previous week, and 44.0% reported some independent student hours. It is possible that parents felt the need to step in even more when school was closed entirely. When the school was online without many school resources, parents may have decided that their inputs were not helpful, and it was a better use of their time to work or search for a job. This is a possible area for future research.

Cabus and Ariës (2017) find that having a ‘school-supportive’ home climate matters and boosts student achievement in Dutch households.

In a newly published study (Gould et al. 2020), find that when educated parents in Israel spent more time with their children, their children are better educated themselves and the link may be due, in part, to the time spent creating human capital together. Furthermore, the more time the parents spent with children, the better the student achievement.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adams-Prassl, A., Boneva, T., Golin, M., & Rauh C. (2020). Inequality in the impact of the coronavirus shock: evidence from real time surveys. Journal of Public Economicshttps://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0047272720301092.

- Attanasio, O., Boneva, T., & Rauh C. (2019). Parental beliefs about returns to different types of investments in school children. NBER Working Paper No. w25513.

- Auxier, B. & Anderson, M. (2020). As schools close due to the coronavirus, some U.S. students face a digital ‘homework gap.’ Pew Research Center, March 16. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/03/16/as-schools-close-due-to-the-coronavirus-some-u-s-students-face-a-digital-homework-gap/.

- Ayhan SH. Married women’s added worker effect during the 2008 economic crisis-The case of Turkey. Review of Economics of the Household. 2018;16(3):767–790. doi: 10.1007/s11150-016-9358-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bacher-Hicks, A., Goodman, J., & Mulhern C. (2020). Inequality in household adaptation to schooling shocks: covid-induced online learning engagement in real time. NBER Working paper No. 27555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Beshears J, Choi J, Iwry J, John D, Laibson D, Madrian B. Building emergency savings through employer-sponsored rainy-day savings accounts. Tax Policy and the Economy. 2020;34(1):43–90. doi: 10.1086/708170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Billman N, Geddes C, Hedges H. Teacher–parent partnerships: sharing understandings and making changes. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood. 2005;30(1):44–48. doi: 10.1177/183693910503000108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Black SE, Devereux P, Salvanes K. Why the apple doesn’t fall far: understanding intergenerational transmission of human capital. American Economic Review. 2005;95(1):437–449. doi: 10.1257/0002828053828635. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bredtmann J, Otten S, Rulff C. Husband’s unemployment and wife’s labor supply: the added worker effect across Europe. ILR Review. 2018;71(5):1201–1231. doi: 10.1177/0019793917739617. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brenen, M. (2020). 42% of parents worry Covid-19 will affect child’s education. Gallup Poll, March 31. https://news.gallup.com/poll/305819/parents-worry-covid-affect-child-education.aspx.

- Browning M, Chiappori P-A, Weiss Y. Economics of the family. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]