Significance

Understanding the relationship between college and political ideology is of increasing importance in the United States in the context of intense partisan polarization. Leveraging a quasi-experiment and a panel survey, we find no evidence that a sample of students moves leftward along the political spectrum during the first year of college. However, we find strong evidence of a causal effect of roommates: Students move toward their randomly assigned roommates’ political ideology over the course of their first year of college. Our study identifies causal evidence of social network effects for political views and identifies these causal effects for college students specifically. Our findings are inconsistent with claims that college makes students more liberal.

Keywords: political ideology, higher education, socialization, political science

Abstract

Does college change students’ political preferences? While existing research has documented associations between college education and political views, it remains unclear whether these associations reflect a causal relationship. We address this gap in previous research by analyzing a quasi-experiment in which university students are assigned to live together as roommates. While we find little evidence that college students as a whole become more liberal over time, we do find strong evidence of peer effects, in which students’ political views become more in line with the views of their roommates over time. This effect is strongest for conservative students. These findings shed light on the role of higher education in an era of political polarization.

Recent evidence demonstrates political polarization in public perceptions of higher education. In general, Republicans in the mass public hold negative views of colleges and universities, while Democrats remain strongly supportive of them (1, 2). Republicans’ views of higher education have become negative only recently—almost entirely since 2015. During this period, the country has seen high-profile protests for progressive causes at Yale University, the University of Missouri, and Evergreen State University, among others. Meanwhile, Republican elites’ rhetoric has become sharply critical of universities. For example, in 2017, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos criticized colleges in a speech she gave to the Conservative Political Action Conference, saying, “faculty from adjunct professors to deans tell you what to do, what to say, and more ominously, what to think.” Conservative media cover campus controversies extensively, and op-eds routinely criticize or defend putative liberal or conservative biases among college faculty, as well as student protestors who shut down academic events sponsored by their ideological opponents (3, 4). These trends—and criticisms of higher education—have only intensified in the months since institutional racism has been on the public agenda following protests against racism instigated by the deaths of George Floyd and others.

Higher education, then, has become a polarizing issue in contemporary American politics. Republicans, in particular, argue that universities pursue a left-progressive political agenda, often illustrated by the supposed epidemic of “political correctness” (5), that they are indoctrinating students to accept Marxist or otherwise leftist dogmas (6), and that conservative students are marginalized or mistreated in university communities (7). Republican politicians have increasingly attacked higher education—by slashing funding for universities, eroding tenure, cutting programs, and the like—and have sought to frame higher education as a front in the culture wars (8).

Consistent with the claims of conservative critics of higher education, research shows that college-educated citizens are, on average, more liberal and more likely to vote for Democrats than are their non−college-educated peers (9–11). While this correlation is solidly established in social scientific literature, direct evidence about the causal effect of institutions of higher education on political preferences is remarkably limited. As such, it remains unknown whether the college experience actually causes people to become more liberal. Furthermore, existing literature has done little to explore one particular pathway of ideological change, socialization: the possibility that students are influenced by their roommates, friends, or classmates.

In order to address these important questions, we analyze data from an original panel study at two large universities in the United States and examine changes in political ideology among first-year college students. Critical to the research design is a quasi-experiment: college students cannot control to whom they are assigned as roommates, and we exploit this exogenous variation. This design approach addresses limitations of naturalistic, observational studies, in which self-selection into college, or into particular experiences within college, is a strong possibility and in which causation is thus impossible to infer.

We find no evidence of broad leftward movement of students after 1 y of college; if anything, students in our sample were slightly more conservative at the end of the year compared to the beginning. Second, the quasi-random assignment of incoming first-year college students to their roommates facilitates a research design that allows us to estimate the causal effect of roommate ideology on student ideology over the course of the first year of college. We find strong evidence of such a pattern, with students moving toward their roommates’ political ideology over the course of their first year of college. Our findings, then, suggest that peer socialization can influence the direction of ideological change in college. The results also challenge claims that students become more liberal during their experiences with higher education.

The Effects of College on Political Ideology

There is little evidence that college causes students to become more liberal, although a few prior studies have uncovered suggestive evidence that liberal faculties or peer groups may lead students to move leftward over the course of their college careers (12–14), and that this leftward drift may endure for decades (15). There are several reasons why the experience of college might affect individuals’ political ideology. Institutions of higher education may influence ideology because college students are actively engaged in the study of advanced bodies of knowledge, which improves their cognitive faculties, which, in turn, produces higher levels of information seeking, processing, and organization—all of which are conducive to political understanding and engagement (16). Furthermore, existing literature suggests that individuals may be open to political socialization whenever their interest in politics grows (17). It is well established that open discussion of politics and the social world—which are common in college—induce higher levels of political engagement (18).

If college does indeed influence political ideology, it is likely that it does so, in part, through socialization—the processes by which individuals learn about the norms and practices of politics from other people. Existing research indicates that, outside of college, socialization plays a central role in shaping individual-level ideology (19–21). For example, a compelling series of findings demonstrates that parental political socialization taking place in childhood and early adolescence powerfully influences political preferences, including ideology (22–25).

In the context of college, students may learn about the norms and practices of college from professors, or from their peers. Previous scholarship has examined the influence of college professors on students’ political beliefs, but this research has yielded scant evidence of effects (26–28). Yet scholars rarely examine peer socialization as a pathway to ideological change among college students. One important exception is Mendelberg et al.’s (29) study, which shows that class−cohort socialization significantly influences students’ economic views: Students in wealthier college cohorts develop more conservative views on economic policy.

We assess a different possible pathway for socialization: that students are influenced by their college roommates. Existing research has found evidence of modest peer effects from college roommates on students’ GPA, as well as their decisions to join social groups such as fraternities (30), on phonetic and linguistic convergence among roommates (31), and on levels of civic and political engagement (20, 32, 33). Additionally, previous studies have found evidence of peer effects for alcohol use (and mixed evidence for other types of substance use) (34, 35). Given the wide range of activities and behaviors known to be shaped by roommates, it is plausible that roommates influence each other’s political views. The objective of this study is thus to examine whether any changes in political ideology among first-year college students might be attributed their roommates.

Research Design and Methods

We analyze the effects of experiences with first-year college roommates on student political ideology through an original two-wave panel survey that was designed to examine a wide range of social and health outcomes. (This study was approved by Institutional Review Boards at the University of Michigan (HUM00030251) and Cornell University (0905000400). Students were shown an informed consent document on the first page of the survey and had to indicate their consent to participate before proceeding with the survey.) The sample consists of first-year college students from two large universities in the United States—one public, one private. The students completed two online surveys: one in August of 2009 (before they began college) and another in March−April of 2010, after living with their roommate for nearly the entire academic year (sample characteristics are presented in SI Appendix, Table S1). First-year students were required to live in campus housing at both universities, and students were randomly assigned to their roommates.* We exploit this random assignment to assess the influence of roommates on students’ ideology over their first year of college.

To recruit study participants, students were sent an introductory letter with a $10 bill and a request to participate (a preincentive with no obligation), and then follow-up emails were sent to those who had not yet responded. All communications included a web link and a randomly assigned log-in ID to participate. The messages also informed students that they were entered into a sweepstakes to win cash prizes regardless of participation. About 70% of students participated in wave 1 (3,501 out of 4,971); of these, 74% (2,589) had at least one roommate who was also a wave-1 responder. Of these 2,589 useable respondents, 63% completed the second wave of the survey. Thus, our analytic sample consists of 1,641 respondents who completed both waves and had a roommate in at least the baseline.† Characteristics of the sample are presented in SI Appendix.

Our measure of the dependent variable captures a key variable in public opinion research: ideological self-identification (36). This question asked students whether they characterize their political views as “Far left,” “Liberal,” “Middle-of-the-road,” “Conservative,” or “Far right.” Students were asked this question on both the baseline and the follow-up survey.‡ The key independent variable is roommate self-identified ideology, measured on the same scale as the dependent variable.§ We also include measures for a variety of potentially relevant factors to include as control variables in supplemental models. Random assignment comes after matching on gender, and accommodating student preferences to the extent possible for room type (double, triple, quad), location on campus, coed versus same-sex hallway, and substance use (e.g., smoking versus nonsmoking). Since we have data on the variables that enter into the roommate assignment decision, we can examine whether these variables are associated with assignment to a roommate with ideology different from that of the respondent; we find no evidence of such associations (SI Appendix, Table S2; for further randomization checks, see SI Appendix, Table S11 and Fig. S1).¶

Since college students are assigned to live with each other as roommates, our research design addresses the key limitation of previous scholarship on this topic: its inability to distinguish between correlation and causation. That is, since students are unable to request roommates whose ideology matches theirs, roommate ideology is plausibly exogenous to student changes in ideology during the first year.# In the following section, we examine descriptive differences in student ideology over time in order to assess the claim that college has a liberalizing effect on students’ political views. We then analyze the quasi-experiment by regressing students’ political views at wave 2 on their roommates’ ideology. Note that, because we are observing the impact of naturalistic contact between people of different political ideology (rather than a deliberate intervention with prescribed interaction), our estimates capture intent to treat (ITT) rather than the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT).

Results and Discussion

Before investigating peer effects, we begin by assessing the distribution of ideology among the same students, in both waves of the survey, in Table 1. The table shows, first, that the students in this sample tend to lean left, consistent with the findings of existing research.

Table 1.

Distribution of student ideology at two points in time

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | |

| August 2009 | March−April 2010 | |

| Far left | 72 (4.4%) | 73 (4.4%) |

| Liberal | 689 (42.2%) | 653 (40.0%) |

| Middle-of-the-road | 584 (35.8%) | 596 (36.5%) |

| Conservative | 276 (16.9%) | 303 (18.6%) |

| Far right | 11 (0.7%) | 7 (0.4%) |

| Total | 1,632 | 1,632 |

Contrary to popular claims about the effects of college on student ideology, however, on balance, the students do not move to the left over the course of their first year in college. In fact, the table reveals a slight average movement in a conservative direction. To test whether this increase is statistically significant, we conduct a two-tailed paired t test, comparing the mean level of ideology in wave 1 to the mean level in wave 2. Here ideology is measured as on a 1 to 5 scale, where “1” is far left and “5” is far right. The mean level of conservatism increases slightly from 2.67 to 2.70, a difference which is statistically significant at P < 0.05. The students in our sample become slightly more conservative, not more liberal, during their first year in college.

Our first finding, then, is one of aggregate stability. The proportions of students in the different ideological categories changes hardly at all between August 2009 (42.2% of the sample identifies as liberal and 16.9% as conservative) and March−April of 2010 (40% of the sample identifies as liberal and 18.6% as conservative).

That said, this null pattern masks countervailing trends: Some individuals move left during the first year, and some move right. This can be seen in Table 2, which is a cross-tabulation of responses to the ideology question across the two waves of the survey.

Table 2.

Changes in student ideology over time

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Total | ||||

| Far left | Liberal | Middle | Conservative | Far right | ||

| Far left | 50 | 20 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 72 |

| Liberal | 23 | 542 | 114 | 10 | 0 | 689 |

| Middle | 0 | 87 | 430 | 67 | 0 | 584 |

| Conservative | 0 | 3 | 49 | 221 | 3 | 276 |

| Far right | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 11 |

| Total | 73 | 653 | 596 | 303 | 7 | 1,632 |

While the majority of students give an identical response to the ideology question in both waves of the survey, summing the off-diagonal responses indicates that, in total, 385 of the 1,632 students (23.6%) change between wave 1 and wave 2. Nearly all of these changes (368) are of only one point on the five-point scale. Of these movers, 216 become more conservative (those above the diagonal), while 169 become more liberal (below the diagonal). The modal respondent who changes her views is a liberal at wave 1 who then reports being moderate at wave 2. Moreover, of the 385 movers, 166 (43.1%) identify as moderates at wave 2.

Next, we ask, Do roommates influence the direction of these individual-level ideological changes during students’ first year in college? To answer this question, we first simply tabulate whether the students with a change in ideology moved toward or away from the ideology of their roommate. Of course, only students who were not the same as their roommates at wave 1 could move toward their roommates, so we focus on those students here (n = 1103). As Table 3 shows, of the students who changed ideology, 252 had a roommate of a different ideology at wave 1, and, of these, 191 (75.6%) moved toward their roommates.|| Furthermore, conservatives were somewhat more likely to move toward their roommates than were liberals.

Table 3.

Changes in student ideology relative to their roommate, among respondents who were assigned to roommate of a different political ideology

| Movement | Respondent ideology wave 1 | Total | ||||

| Far left | Liberal | Middle | Conservative | Far right | ||

| Away from roommate | 0 | 17 | 43 | 1 | 0 | 61 |

| No change | 50 | 345 | 277 | 175 | 4 | 851 |

| Toward roommate | 20 | 72 | 46 | 46 | 7 | 191 |

Next, we estimate a series of ordinary least squares multivariate regression models.** In all models, the dependent variable is the student’s ideology at wave 2, and the independent variable of interest is the roommate’s ideology at wave 1, while a key control variable is the student’s ideology at wave 1. This approach allows us to assess whether roommate ideology predicts changes in student ideology over time. Model 1 includes no additional control variables, while model 2 includes a control for institution.†† Since students were allowed to express preferences for different kinds of roommates (although not roommate political beliefs), which influenced the roommate selection process, model 3 includes control variables for students’ expressed roommate preferences, and model 4 includes controls for other roommate characteristics: binge drinking, smoking, drug use, gambling, multiple sex partners, psychological distress, parents’ educational attainment, religiosity, exercise frequency, average number of study hours, and standardized test scores. Model 5 includes controls for the characteristics of the respondents themselves, including gender, race, religiosity, and sexual orientation. Finally, model 6 includes all of the controls from models 2 to 5 (full models are presented in SI Appendix). In all models, we cluster SEs at the room.‡‡

As shown in Table 4, roommate ideology in wave 1 is indeed associated with student ideology in wave 2, even after controlling for student ideology at wave 1. In other words, over the course of the first year in college, students’ ideology tends to move toward the ideology of their roommates. The models presented in Table 4 indicate that roommate ideology is related to changes in students’ ideology over the course of their first year of college, with P values ranging from 0.012 to 0.069.§§ However, this significant association is relatively small in magnitude, as might be expected given that ideology does not change for the majority of students during this time period, and given that these students are included in the regression analysis.

Table 4.

Associations between roommate ideology (wave 1) and student ideology (wave 2)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Roommate ideology | 0.031 | 0.031 | 0.031 | 0.039 | 0.032 | 0.046 |

| SE | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.015 | 0.018 |

| P value | 0.051 | 0.054 | 0.069 | 0.026 | 0.042 | 0.012 |

| Control variable(s) | ||||||

| Student ideology (w1) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Other controls | — | Institution | Roommate Preferences | Roommate Characteristics | Student Characteristics | All (2 to 5) |

Here n = 1,632. All models are OLS regressions. Both roommate ideology and student ideology are coded on a scale of 1 to 5. The check marks indicate that wave-1 (w1) student ideology is controlled for. For the full table of coefficient estimates (including control variables), see SI Appendix, Table S4.

Next, we focus more specifically on students assigned to roommates who had different baseline political views. Here we specify “treatment” as the signed ideological distance between the respondent and their roommate at wave 1. The control group is those assigned to a roommate of the same ideology as themselves at wave 1. The outcome of interest is the signed change in respondent ideology from wave 1 to wave 2 (w2 − w1). The effect of treatment (here, the ATT) is estimated using ordinary last squares (OLS) with SEs clustered at the room level (SI Appendix, Table S5). This approach allows us to examine whether students move toward their roommates, as well as whether the effect is similar for students across the ideological spectrum (see SI Appendix, Table S12 for subgroup analysis).

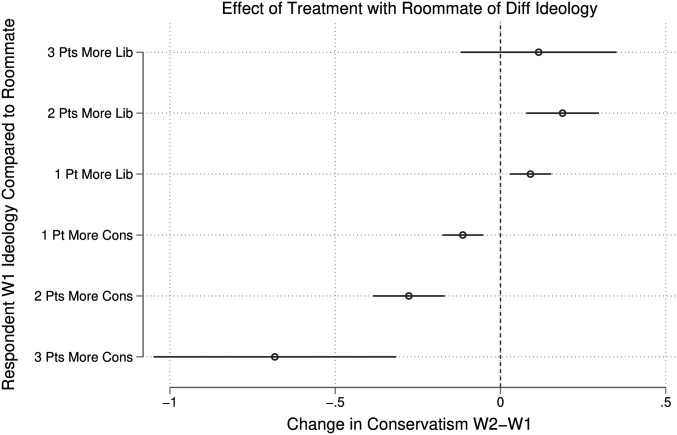

As demonstrated in Fig. 1, treatment with an ideologically different roommate exerts strong and statistically significant influence on the respondents’ ideology at wave 2, and in the expected direction.¶¶ In Fig. 1, respondent−roommate dyads with the same ideology at wave 1 are the baseline: the group to which the others are compared. For the most part, these responses are similar in magnitude on either side of the ideological spectrum. For example, if a student is three points on the scale more conservative than her roommate (i.e., the roommate is much more liberal than the respondent at wave 1), then the respondent moves, on average, about 0.6 points to the left (i.e., toward her roommate) by wave 2. Similarly, if a student is two points more liberal than her randomly assigned roommate, the student is significantly likely to be more conservative, by about 0.2 points, at wave 2 than she had been at wave 1. The only level of treatment that does not comport to this pattern is for those who are three points more liberal than their roommates. For these students, we do not find a statistically significant effect of roommate ideology. The absence of a discernible effect is likely due to a dearth of observations in this treatment level: Because of relatively low numbers of conservative and far right students at wave 1, very few respondents in the study were assigned to a roommate who was three or more points more liberal than they were (n = 59). All of these effects are robust to inclusion of the batteries of controls discussed above, as we show in SI Appendix, Table S5. Moreover, this finding is corroborated by the fact that the mean difference in ideology between roommates is smaller at wave 2 than at wave 1 among those roommate pairs whose ideology differed at the beginning of the study (1.24 at wave 1, compared to 1.11 at wave 2; a two-tailed paired t test shows this difference is significant at P < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Effect of roommate distance on change in student Ideology.

Conclusion

Social scientists have long been interested in the relationship between college education and political preferences. In recent years, questions about this relationship have reached beyond the academy to mainstream political discourse as well. Pundits and political elites routinely claim that higher education influences students’ political preferences, but high-quality evidence to evaluate this claim is in short supply.

Our study shows that the ideology of first-year college students in our sample does not change much over the course of their first year on campus, contrary to the stated fears of many high-profile conservative pundits. Moreover, to the extent that there are aggregate changes, they are generally in the conservative direction: There are more moderates and more conservatives, but fewer liberals, in the second wave of our panel than in the first.

We also leverage a quasi-experiment to test a key theoretical pathway by which ideology might change during college: socialization. We find strong evidence that college student ideology is influenced by the ideology of their roommate. We also find that the influence of roommate ideology is largely similar for students who are on either side of the ideological spectrum. Given our finding of the importance of socialization, along with the findings of other research (29), we suspect that influences of college experiences on student ideology might be found less in the classroom than in the dormitory.

There are a few limitations of this study that might productively be addressed by future scholarship. First, the five-category measure of ideology used here is slightly different from the seven-category measure often used in political science (37), and the truncated variation in the measure of this study may bias the findings toward zero. Second, although we find strong evidence that socialization is a key path of ideology change among college students, our data do not allow us to say why or how this effect obtains. Identifying the mechanisms through which roommate ideology influences students’ political views is an important avenue of future research on this topic.## Finally, the survey was conducted in 2009–2010. Future research might do well to consider whether continuing polarization—particularly partisan polarization over higher education within the mass public—is changing the dynamics of peer socialization in higher education today.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Giancarlo Visconti, Ben Johnson, and the anonymous referees for helpful comments on previous drafts; those members of campus staff who helped collect administrative data; and the students who participated in the surveys. A research grant from the William T. Grant Foundation funded this study, and Survey Sciences Group, LLC administered the survey data collection process.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

*We spoke with housing assignment officials at both universities and confirmed that there is no human element to the matching, nor any additional information being used besides the variables that we control for. The measures were not the same across the two institutions. One institution used a short list of variables (gender, coed/same sex hallway, smoker, campus area), and the other used a much longer list. The full questionnaires are presented in SI Appendix. Thus, while we don’t know the exact randomization algorithms they used, we are confident that the assignments were random conditional on the assignment variables we control for. We also note that, at both universities, students did have the option to request a roommate, and we omitted all of those students from the study. We limited the study sample to students who did not request a roommate and were therefore assigned to roommates.

†Because our analytic sample consists of only about 33% of possible respondents, it is important to examine potential biases related to nonresponse or panel attrition. To do so, we compare respondent characteristics across different levels of attrition in SI Appendix, Table S3, and find scant differences. The results suggest that attrition does not bias our estimates of the causal effect.

‡One limitation to this study we must acknowledge is that this is not the standard seven-point scale typically used to measure ideology.

§When students have multiple roommates, we use the average of the wave 1 ideology of the roommates.

¶These data were obtained from the housing offices of both schools.

#Additionally, we note that we perfectly observe all expressed roommate preferences that were incorporated into the roommate assignment process, and therefore are confident that roommate ideology does not correlate with measurement error in respondent ideology.

||These findings are substantively identical when we exclude students who started at the extremes of the distribution—that is, when we exclude those who could only move toward their roommate, if they were to move. See SI Appendix, Table S6.

**The same patterns are evident if ordered logit is used instead of OLS.

††We also conducted separate analyses for each institution, finding similar patterns for both: For the public institution, the coefficient on roommate ideology is 0.03 (SE is 0.02), and, for the private institution, the coefficient is 0.02 (SE is 0.03). See SI Appendix, Tables S7 and S8 for full analysis of the separate institutions.

‡‡Note that our estimates may be biased toward zero. Consider the possibility that reported values of the wave 2 measurement of Y may reflect relative comparisons with one’s roommate’s ideology. For example, if a somewhat conservative student is paired with a somewhat liberal roommate, they might view themselves as very conservative and very liberal (i.e., moving away from each other in political orientation) after living together, even if their true political orientations have not changed. If true, such relative comparisons would bias us in the opposite direction from the spillover effects that we report here.

§§See also SI Appendix, Fig. S2, which shows that this finding is robust to alternative specification using a randomization inference approach.

¶¶We show, in SI Appendix, that this finding is robust to estimation approaches that account for uneven probability of assignment to a roommate of different ideology than the respondent at wave 1: inverse probability weighting and propensity score matching. Because the distribution of student ideology at wave 1 is not uniform (Table 1), the likelihood of assignment to a liberal roommate is greater than the likelihood of assignment to a conservative roommate. We conceptualize treatment first as assignment to a roommate of different ideology than the respondent, and use propensity score matching (matched on the variables reported in Table 4) to estimate the ATT (SI Appendix, Table S10). We also conceptualize different levels of treatment (the absolute distance between respondent and roommate ideology at wave 1) and use inverse probability weighting to account for uneven probability of assignment into these different levels of treatment (SI Appendix, Tables S9(1)–S9(4)). Both of these approaches show strong evidence of treatment effects.

##In SI Appendix, Table S13, we present a causal mediation analysis which provides no support for the theory that the causal effect is mediated by roommate friendship.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2015514117/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

A restricted data set is available on request at: https://healthymindsnetwork.org/research/data-for-researchers/ (38).

References

- 1.Bump P., The new culture war targeting American universities appears to be working. The Washington Post, 10 July 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/politics/wp/2017/07/10/the-new-culture-war-targeting-american-universities-appears-to-be-working/. Accessed 5 June 2020.

- 2.Brown A., “Most Americans say higher ed is heading in wrong direction, but partisans disagree on why” (Pew Research Center, 26 July 2018). https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/07/26/most-americans-say-higher-ed-is-heading-in-wrong-direction-but-partisans-disagree-on-why/. Accessed 5 June 2020.

- 3.Barrett J., How politically biased are colleges? New study finds it’s far worse than anybody thought. The Daily Wire, 3 May 2018. https://www.dailywire.com/news/how-politically-biased-are-universities-new-study-james-barrett. Accessed 5 June 2020.

- 4.Cooley L., Liberalism is rampant on campus and ruining academia. Washington Examiner, 6 September 2018. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/red-alert-politics/liberalism-is-rampant-on-campus-and-ruining-academia. Accessed 5 June 2020.

- 5.Lucas R., Sessions condemns ‘‘political correctness’’ on college campuses. All Things Considered, 26 September 2017. https://www.npr.org/2017/09/26/553799118/sessions-condemns-political-correctness-on-college-campuses. Accessed 5 June 2020.

- 6.Blakely J., A history of the conservative war on universities. The Atlantic, 7 December 2017. https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2017/12/a-history-of-the-conservative-war-on-universities/547703/. Accessed 30 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaufman E., The next right-wing populist will win by attacking American higher education. National Review, 13 July 2017. https://www.nationalreview.com/2017/07/right-wing-populism-next-target-american-higher-education/. Accessed 5 June 2020.

- 8.Thompson D., The Republican war on college. The Atlantic, 7 November 2017. https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2017/11/republican-college/546308/. Accessed 30 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldman K. A., Newcomb T. M., The Impact of College on Students (Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA, 1969). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pascarella E. T., Terenzini P. T., How College Affects Students (Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA, 1991). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanson J. M., Weeden D. D., Pascarella E. T., Blaich C., Do liberal arts colleges make students more liberal? Some initial evidence? High. Educ. 64, 355–369 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newcomb T. M., Personality and Social Change: Attitude Formation in a Student Community (Dryden, 1943). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunt E., Davignon P., The invisible thread: The influence of liberal faculty on student political views at evangelical colleges. J. Coll. Character 17, 175–189 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lottes I. L., Kuriloff P. J., The impact of college experience on political and social attitudes. Sex Roles 31, 31–54 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newcomb T. M., Koenig K. E., Flacks R., Warwick D. P., Persistence and Change: Bennington College and Its Students after 25 Years (Wiley, 1967). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nie N. H., Junn J., Stehlik-Barry K., Education and Democratic Citizenship in America (University of Chicago Press, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jennings M. K., Stoker L., Bowers J., Politics across generations: Family transmission reexamined. J. Polit. 71, 780–799 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahne J., Crow D., Lee N.-J., Different pedagogy, different politics: High school learning opportunities and youth political engagement. Polit. Psychol. 34, 419–441 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Funk C. L., et al. , Genetic and environmental transmission of political orientations. Polit. Psychol. 34, 805–819 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klofstad C. A., The lasting effect of civic talk on civic participation: Evidence from a panel study. Soc. Forces 88, 2353–2375 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jost J. T., Federico C. M., Napier J. L., Political ideology: Its structure, functions, and elective affinities. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 60, 307–337 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gidengil E., O’Neill B., Young L., Her mother’s daughter? The influence of childhood socialization on women’s political engagement. J. Women Polit. Policy 31, 334–355 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coffe H., Voorpostel M., Young people, parents and radical right voting: The case of the Swiss People’s Party. Elect. Stud. 29, 435–443 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dinas E., Why does the apple fall far from the tree? How early political socialization prompts parent-child dissimilarity. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 44, 827–852 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sapiro V., Not your parents’ political socialization: Introduction for a new generation. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 7, 1–23 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly-Woessner A., Woessner M. C., My professor is a partisan hack: How perceptions of a professor’s political views affect student course evaluations. PS Polit. Sci. Polit. 39, 495–501 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelly-Woessner A., Woessner M. C., I think my professor is a Democrat: Considering whether students recognize and react to faculty politics. PS Polit. Sci. Polit. 42, 343–352 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mariani M. D., Hewitt G. J., Indoctrination U.? Faculty ideology and changes in student political orientation. PS Polit. Sci. Polit. 41, 773–783 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mendelberg T., McCabe K. T., Thal A., College socialization and the economic views of affluent Americans. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 61, 606–623 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sacerdote B., Peer effects with random assignment: Results for Dartmouth roommates. Q. J. Econ. 116, 681–704 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pardo J. S., Gibbons R., Suppes A., Krauss R. M., Phonetic convergence in college roommates. J. Phonetics 40, 190–197 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klofstad C. A., Civic Talk: Peers, Politics, and the Future of Democracy (Temple University Press, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klofstad C. A., Exposure to political discussion in college is associated with higher rates of political participation over time. Polit. Commun. 32, 292–309 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eisenberg D., Golberstein E., Whitlock J. L., Peer effects on risky behaviors: New evidence from college roommate assignments. J. Health Econ. 33, 126–138 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kremer M., Levy D., Peer effects and alcohol use among college students. J. Econ. Perspect. 22, 189–206 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conover P. J., Feldman S., The origins and meaning of liberal/conservative self-identifications. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 25, 617–654 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kinder D. R., Kalmoe N., Neither Liberal nor Conservative (University of Chicago Press, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strother L., Piston S., Golberstein E., Gollust S. E., Eisenberg D., Healthy Minds Network (2020). University of Michigan. Ann Arbor, MI. Restricted data set available through https://healthymindsnetwork.org/research/data-for-researchers/. Deposited 8 December 2014.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

A restricted data set is available on request at: https://healthymindsnetwork.org/research/data-for-researchers/ (38).