Significance

Cas9 complexed with a programmable guide RNA has been repurposed for genome-engineering applications. Mechanistic understanding of Cas9-mediated DNA cleavage provides opportunities for rational engineering of Cas9 to improve its efficiency and specificity. Domain movements of Cas9 have been well studied before DNA cleavage but not after. In this study, we observed the HNH nuclease domain motions from DNA binding to post-DNA cleavage in real time using single-molecule fluorescence techniques. The coupling between DNA cleavage activity and Cas9 conformation demonstrated in our study provides insights and motivation for future applications.

Keywords: CRISPR-Cas9, single molecule, conformational rearrangement

Abstract

CRISPR-Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes is an RNA-guided DNA endonuclease, which has become the most popular genome editing tool. Coordinated domain motions of Cas9 prior to DNA cleavage have been extensively characterized but our understanding of Cas9 conformations postcatalysis is limited. Because Cas9 can remain stably bound to the cleaved DNA for hours, its postcatalytic conformation may influence genome editing mechanisms. Here, we use single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer to characterize the HNH domain motions of Cas9 that are coupled with cleavage activity of the target strand (TS) or nontarget strand (NTS) of DNA substrate. We reveal an NTS-cleavage-competent conformation following the HNH domain conformational activation. The 3′ flap generated by NTS cleavage can be rapidly digested by a 3′ to 5′ single-stranded DNA-specific exonuclease, indicating Cas9 exposes the 3′ flap for potential interaction with the DNA repair machinery. We find evidence that the HNH domain is highly flexible post-TS cleavage, explaining a recent observation that the HNH domain was not visible in a postcatalytic cryo-EM structure. Our results illuminate previously unappreciated regulatory roles of DNA cleavage activity on Cas9’s conformation and suggest possible biotechnological applications.

The CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats)-Cas (CRISPR-associated) system targets foreign nucleic acids for destruction in bacteria and archaea (1). Among different types of the system, CRISPR-Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes has been widely used for genome editing in plant and animal cells (2–5). DNA cleavage by the CRISPR-Cas9 system involves multiple steps (6). The Cas9 enzyme associates with a guide RNA, consisting of a programmable CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and a transactivating RNA (tracrRNA), to form a Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complex (RNP) (7). The DNA substrate of Cas9 RNP contains a protospacer region complementary to the spacer sequence of crRNA, and a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) (NGG for S. pyogenes Cas9) flanking the protospacer (7). After Cas9 RNP binding, the DNA is directionally unwound from the PAM-proximal region to the PAM-distal region (8–10), and the unwound target strand (TS) is hybridized to the spacer sequence of crRNA. The TS and nontarget strand (NTS) of the DNA are cleaved by the HNH domain (residue 780 to 906) and the RuvC domain (residues 1 to 56, 718 to 765, and 926 to 1,099), respectively (7, 11). Engineering of the active site of the HNH domain or RuvC domain creates NTS nickase (Cas9dHNH, Cas9 with H840A mutation which cleaves NTS only) or TS nickase (Cas9dRuvC, Cas9 with D10A mutation which cleaves TS only) (7). The TS and NTS Cas9 nickases have also been used in many genome editing applications to achieve higher editing specificity or avoid generating double-stranded breaks (12–14). Cas9 RNP remains stably bound to the cleaved DNA for hours in vitro (8, 9, 15, 16), likely hindering DNA repair processes in cells (15). Therefore, a characterization of the postcatalysis state of Cas9 and its nickase variants has the potential to provide insights into genome editing mechanisms.

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) and structural studies have demonstrated the key roles of the HNH domain conformation in Cas9-mediated DNA cleavage (17–24). The HNH domain undergoes large conformational changes from the “undocked” inactive conformations to the “docked” active conformation with respect to its TS substrate upon on-target DNA binding, which represents a conformational activation of the HNH domain preceding DNA cleavage (18, 19). The HNH activation also involves conformational changes of the REC2 domain (residue 167 to 307) and REC3 domain (residue 497 to 713) (25). The HNH domain was not visible in a recent cryo-EM structure of the “product” state Cas9-RNA-DNA complex, suggesting the HNH domain is flexible after DNA cleavage (26). However, the previous FRET study showed that the docked conformation persists after DNA cleavage and the product state HNH domain motions were not observed (except for a special case in which the 3′ flap of the NTS was completely removed after DNA cleavage) (18), possibly because the labeling positions for the FRET donor and acceptor pair were not sensitive to the conformational differences between the docked state and the product state of the HNH domain. In this study, we created new Cas9 FRET constructs with increased sensitivity to small distance changes between the FRET pair and observed postcatalytic HNH domain motions using single-molecule FRET.

Results

Single-Molecule FRET Constructs.

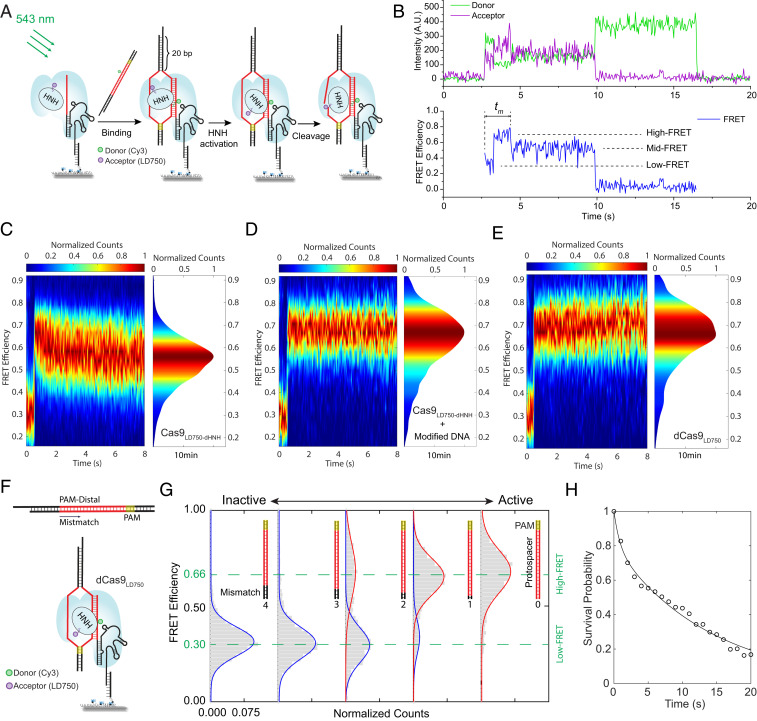

To test DNA cleavage-related Cas9 conformational changes using single-molecule FRET, a single cysteine in the SpCas9 variant (C80S/C574S/E873C) was labeled with an acceptor (photostable Cy7 derivative, LD750). We hereafter refer to the LD750-labeled Cas9 variant as Cas9LD750. We chose LD750 instead of Cy5 as the FRET acceptor in an effort to make FRET more sensitive to small distance changes (27). The acceptor labeling site, residue 873, is within the HNH domain (Fig. 1A). The TS was labeled with a donor (Cy3) which is six nucleotides (nt) away from the PAM region into the protospacer (Fig. 1B). The HNH domain adopts multiple conformations during the DNA targeting and cleavage, and its conformation in the product state was not resolved (Fig. 1A) (26). In contrast, the TS was resolved in all structures. Therefore, the Cy3 on TS is a stationary point against which HNH domain movement can be measured from the Cy3-LD750 FRET efficiency changes (Fig. 1A). The TS nickase variant of Cas9LD750 (named Cas9LD750-dRuvC, Cas9LD750 with D10A mutation), NTS nickase variant of Cas9LD750 (named Cas9LD750-dHNH, Cas9LD750 with H840A mutation), and the catalytically dead version of Cas9LD750 (named dCas9LD750, Cas9LD750 with D10A and H840A mutations) were also prepared. The labeling efficiency of LD750 measured in bulk using a spectrophotometer was 61 to 77% (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). To measure the labeling efficiency of LD750 in Cas9-RNA-DNA ternary complex using single-molecule FRET, we immobilized the Cy3-LD750 labeled Cas9-RNA-DNA ternary complex to a polymer-passivated quartz slide via biotin-NeutrAvidin interactions, we found 65 to 75% Cy3 signals colocalized with LD750 signals of single-cysteine Cas9 variants, suggesting that 65 to 75% Cas9-RNA-DNA ternary complexes were labeled with LD750 (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 B and C and SI Materials and Methods show details). Cas9LD750 was functional in cleaving the Cy3-labeled double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), although the cleavage kinetics was slower compared to wild-type Cas9 cleaving dsDNA without any labeling or modification (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A and B), as was observed from a previous study utilizing labeled Cas9 (17). We confirmed that Cas9LD750-dHNH and Cas9LD750-dRuvC cleave only the NTS and the TS, respectively (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). dCas9LD750 is catalytically dead for DNA cleavage (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C).

Fig. 1.

DNA cleavage-induced Cas9 conformational changes revealed by single-molecule FRET. (A) Conformational states of the Cas9-RNA-DNA complex in the presence of Mg2+ revealed by cryo-EM (PDB: 6O0Z, 6O0Y, and 6O0X). The target strand (blue) was labeled with Cy3 (green), and the HNH domain (yellow) was labeled with LD750 (purple). The HNH domain was not resolved in the product complex. In contrast, the target strand was resolved in all structures. (B, Top) Schematic for Cy3-labeled dsDNA substrate. The sequence of DNA target and guide RNA can be found in SI Appendix, Table S1. (B, Bottom) Schematic for smFRET construct to investigate DNA cleavage-induced Cas9 conformational changes. (C) FRET histograms before (Top) and after (Bottom) DNA cleavage in the EDTA-containing buffer. Green or red curve represents a fit to a single Gaussian peak. Blue curve represents a fit to a single or double Gaussian peaks.

TS and NTS Cleavage Differently Affect Cas9 Conformations in the Absence of Mg2+.

To compare Cas9 conformations before and after DNA cleavage, the labeled Cas9-RNA-DNA ternary complex was assembled in an ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-containing buffer (10 mM EDTA) to prevent cleavage (18), and immobilized via a biotin on the DNA to a polymer-passivated quartz slide (Fig. 1B). Histograms of single-molecule FRET efficiencies, E, before cleavage were similar across all Cas9 variants (Fig. 1C, Top row). E fluctuated between two states (E ∼ 0.67 and E ∼ 0.83) in single-molecule FRET time traces (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). Conformational fluctuations of the HNH domain before DNA cleavage in the absence of Mg2+ were also observed in a high-speed atomic force microscopy study (28). We then incubated the sample in a Mg2+-containing buffer (5 mM Mg2+) for 10 min, which induces cleavage of the majority (≥85%) of DNA (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 C and D), and obtained FRET histograms of the postcleavage state after exchanging the solution back to the EDTA-containing buffer (Fig. 1C, Bottom row). The histograms before and after the Mg2+ pulse were nearly identical for dCas9LD750 (Fig. 1C). In contrast, Cas9LD750-dRuvC showed an increase in the E ∼ 0.67 population at the expense of the E ∼ 0.83 population after the Mg2+ pulse (Fig. 1C) and did not shift further with a longer Mg2+ pulse (20 min) (SI Appendix, Fig. S4), suggesting that TS cleavage caused some changes in Cas9 conformational dynamics. TS-crRNA heteroduplex forms extensive interactions with the REC3 domain, which is known to regulate the HNH conformations (25). Our observation supports a model that TS cleavage may cause a slight conformational change of the TS-crRNA heteroduplex, which further alters the conformational dynamics of the REC3 domain and the HNH domain. However, the two-state E fluctuations were still observed after the Mg2+ pulse (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). Remarkably, the postcleavage histograms of Cas9LD750 and Cas9LD750-dHNH were very different from their precleavage histograms and showed a single peak at E ∼ 0.64 (Fig. 1C), and we did not observe E fluctuations between distinct FRET states (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B), indicating the scissile phosphate of the NTS has an important role in the conformational dynamics of the HNH domain as detected in the absence of Mg2+.

DNA Landing Assays Reveal a Mid-FRET Conformation Coupled with NTS Cleavage Activity in the Presence of Mg2+.

The above FRET measurements were performed in the absence of Mg2+. To further investigate how Cas9 conformations are coupled with DNA cleavage activity in the presence of Mg2+, we performed a single-molecule DNA landing assay in the Mg2+-containing buffer, where binding of donor-labeled DNA to a surface-tethered Cas9 RNP was detected as a sudden appearance of fluorescence signals (Fig. 2 A and B). We first investigated the effects of NTS cleavage activity on the conformation of the HNH domain. To avoid potential complications caused by TS cleavage activity, for these experiments we used Cas9LD750-dHNH and dCas9LD750 which cannot cleave the TS. A representative single-molecule FRET time trace from Cas9LD750-dHNH shows three FRET states that are sequentially visited: an initial, transient low-FRET state (E ∼ 0.30), followed by a transient high-FRET state (E ∼ 0.66), and then a relatively steady mid-FRET state (E ∼ 0.55) (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

DNA landing assay reveals a mid-FRET state coupled with NTS cleavage activity. (A) Schematic for the DNA landing assay to investigate conformational rearrangements of the HNH domain during DNA binding to Cas9 and nontarget strand cleavage by Cas9. The same DNA substrate in Fig. 1B was used here but the biotinylated ssDNA was omitted. The sequence of DNA target and guide RNA can be found in SI Appendix, Table S1. (B) Representative FRET trace of the DNA landing assay from Cas9LD750-dHNH. The low-FRET, high-FRET, and mid-FRET states are indicated. tm is the time the molecule takes to transit to the steady mid-FRET state after binding. (C–E) FRET kymograph from 0 to 8 s (Left) and FRET histogram (Right) at 10 min after DNA binding to Cas9 using Cas9LD750-dHNH (C), Cas9LD750-dHNH with phosphorothioate-modified on-target dsDNA with Cy3 (D), and dCas9LD750 (E). A total of 149 to 390 single-molecule FRET traces were used in each FRET kymograph. (F, Top) Schematic for Cy3-labeled dsDNA substrate with PAM-distal mismatches. (F, Bottom) Schematic for immobilized dCas9LD750-RNA-DNA complex for FRET measurements. (G) FRET histograms measured at 10 min after DNA binding to dCas9LD750 using DNA with four to one PAM-distal mismatches against guide RNA. Each curve shows fit to a Gaussian function. (H) Survival probability distributions of tm after photobleaching correction. Black curve shows fit to a double-exponential function. See Photobleaching Correction for the Survival Probability Plot of tm in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods for details.

Next, we assessed whether the low-high-mid FRET transitions represent an obligatory pathway. By examining 188 single-molecule traces, we found 97% (182/188) transiently visited the low-FRET state after DNA binding, then transited to higher FRET states. Only 3% of the molecules (6/188) remained at the low-FRET state until photobleaching (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). Following the low-to-high FRET transition, we observed the high-to-mid FRET transition in 53% (100/188) (Fig. 2B). Six percent (12/188) directly transited to the mid-FRET after the transient low-FRET state, probably because some short-lived states are not detected due to the finite time resolution (50 ms) (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). In a minor fraction of molecules (28/188), a E ∼ 0.92 FRET state was also observed (SI Appendix, Fig. S5C) and only 5 of them showed a subsequent transition to the mid-FRET state (SI Appendix, Fig. S5D). The FRET transitions observed in the DNA landing assay of Cas9LD750-dHNH are summarized (SI Appendix, Fig. S5E). At 10 min after DNA binding, 95% of the molecules (98/103) were found in the mid-FRET state (SI Appendix, Fig. S6), indicating the mid-FRET state persisted after NTS cleavage. These data suggest that, although molecule-to-molecule variability exists, the low-high-mid FRET transition is the main pathway to achieve the mid-FRET conformation. The low-FRET, high-FRET, and mid-FRET states are clearly visible on a kymograph of E values plotted by aligning FRET traces of molecules at the time point of low-to-high FRET transition (Fig. 2C). Control experiments using dCas9LD750 or a noncleavable phosphorothioate-modified DNA showed no detectable NTS cleavage (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C) and did not show the mid-FRET state (Fig. 2 D and E and SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Because the mid-FRET state was observed from the NTS-cleaving construct (Fig. 2C), but not from the constructs without NTS-cleavage activity (Fig. 2 D and E), we conclude that the steady mid-FRET state is coupled with NTS cleavage activity.

We hypothesized that the low- and high-FRET states observed in the DNA landing assay represent the undocked and the docked conformations of the HNH domain, respectively, before DNA cleavage (17, 18). To test this hypothesis, we measured FRET histograms of dCas9LD750 in the Mg2+-containing buffer using DNA with zero to four mismatches against guide RNA at the PAM-distal end of the protospacer (Fig. 2F). With four PAM-distal mismatches, the low-FRET state was prominently populated (Fig. 2G). As the number of PAM-distal mismatches decreased, the low-FRET population progressively decreased with an accompanying increase in the high-FRET population (Fig. 2G). For the on-target DNA, the high-FRET state was prominently populated (Fig. 2G). This trend is well corelated with the PAM-distal mismatch dependence of DNA cleavage efficiency (17, 29), HNH conformations (17, 18), and DNA unwinding activity of Cas9 (30, 31). Thus, we designated the low-FRET state and high-FRET state as the undocked and docked conformations of the HNH domain preceding DNA cleavage (Fig. 2G). The transition from the low-FRET state to the high-FRET state observed in the DNA landing experiments then represents the HNH domain activation upon DNA binding (Fig. 2 B–E and SI Appendix, Fig. S7), consistent with previous studies (17, 18). The observation of the high-to-mid FRET transition suggests the docked HNH conformation does not persist if NTS can be cleaved (Fig. 2C).

Next, we measured the time tm it takes for Cas9LD750-dHNH RNP to achieve the steady mid-FRET state after DNA binding (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S8A). We examined 140 single-molecule FRET traces from the DNA landing assay of Cas9LD750-dHNH (Fig. 2 A and B), and the survival probability of tm was plotted (Fig. 2H) after Cy3-LD750 photobleaching correction (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 and SI Materials and Methods show details). A double-exponential function was fitted to the survival probability (Fig. 2H), which yields 20.3% of the molecules with the time constant of 0.83 s and 79.7% with the time constant of 13.1 s. To investigate whether the HNH domain achieves the steady mid-FRET state before or after NTS cleavage, the time tc it takes Cas9LD750-dHNH RNP to cleave the NTS was measured from gel-based cleavage assays, which yields tc = 56.2 s (SI Appendix, Fig. S9A). Of note, the gel-based assays may underestimate the cleavage rate because it involved both DNA binding and cleavage reactions. To estimate the association rate kBinding of Cas9LD750-dHNH to the DNA target, a Cas9 binding assay was performed (SI Appendix, Fig. S9B). Cas9LD750-dHNH RNP was added to the polymer-passivated quartz slide with preimmobilized DNA molecules, and the time tBinding it takes for Cas9LD750-dHNH RNP to bind to the DNA molecules was measured by examining individual single-molecule traces (SI Appendix, Fig. S9 B and C). The association rate kBinding of Cas9LD750-dHNH RNP to the DNA molecules was proportional to the concentration of Cas9LD750-dHNH RNP after photobleaching correction, with a slope of 0.0032 (nM−1 s−1) (SI Appendix, Fig. S9 D–G and SI Materials and Methods show details of the photobleaching correction for tBinding). Under the experimental condition of the gel-based cleavage assay (i.e., 100 nM Cas9LD750-dHNH RNP and 1 nM DNA), the binding kinetics (kBinding = 100 nM * 0.0032 nM−1 s−1 = 0.32 s−1) is much faster than the measured cleavage kinetics (kc = 1/tc = 0.0178 s−1), indicating the time tc measured from the gel-based cleavage assay is a good estimation of the cleavage kinetics of Cas9LD750-dHNH RNP. The time constant for NTS cleavage is larger than the time constant for acquiring the mid-FRET state, suggesting the HNH domain more likely achieves the steady mid-FRET state before NTS cleavage. Because the mid-FRET conformation was only observed in the NTS-cleaving experiment (Fig. 2 B and C), our data support a model that mid-FRET state represents an NTS-cleavage-competent conformation, and the D10A mutation or phosphorothioate modification at the scissile bond of NTS prohibits the HNH domain from acquiring the NTS-cleavage-competent conformation, thereby preventing NTS cleavage.

The 3′ Flap of the Cleaved NTS Is Susceptible to Exonuclease Digestion.

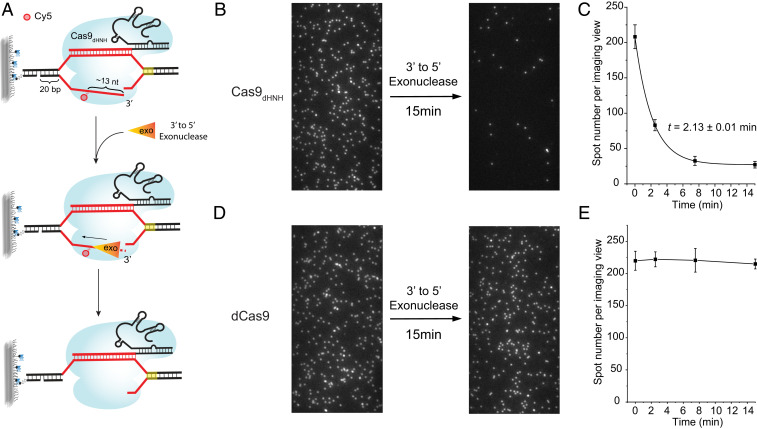

After NTS cleavage, the TS in the protospacer remains annealed to the guide RNA (26). Thus, the cleaved NTS generates a 3′ flap up to 17 nt in length. This 3′ flap was previously proposed as a preferential target of complementary donor strand for homology-dependent repair (15). To directly assess the accessibility of the 3′ flap, we developed a NTS digestion assay where a 3′-to-5′ single-stranded DNA (ssDNA)-specific exonuclease can bind and digest the 3′ flap (Fig. 3A). We first performed the NTS digestion assay using the Cas9 nickase for NTS (Cas9dHNH). In this assay, the NTS of the DNA was labeled with Cy5 at the 16th nt from the PAM without affecting cleavage activity (30) and the Cas9dHNH-RNA-DNA complex was immobilized on a quartz slide surface (Fig. 3A). By shining a 641-nm laser, the average number of Cy5 spots per imaging area was determined (Fig. 3 B and C, “0-min” time point). Next, a 3′-to-5′ ssDNA exonuclease (Klenow fragment) was added, and the average number of Cy5 spots per imaging area was determined as a function of time (Fig. 3 A–C). Remarkably, the Cy5 spots disappeared with time, with an average lifetime of 2.13 ± 0.01 min (Fig. 3 B and C). A control experiment performed using dCas9 did not show Cy5 spot number decrease (Fig. 3 D and E). Therefore, the loss of Cy5 signal when using Cas9dHNH was due to the 3′-to-5′ exonuclease digestion activity on the 3′ flap, releasing Cy5 from the surface (Fig. 3A). Together, our data suggest that the 3′ flap of the cleaved NTS is exposed and can be efficiently digested by exonucleases.

Fig. 3.

Cas9 exposes the 3′ flap of the cleaved NTS for exonuclease digestion. (A) Schematic for the NTS digestion assay. (B) Representative imaging views of the NTS digestion assay using Cas9dHNH before and after adding 3′ to 5′ exonuclease (Klenow fragment). Note that the images were taken at different locations on the slide surface. (C) Quantification of spot numbers per imaging view at different time points after adding 3′ to 5′ exonuclease in the NTS digestion assay using Cas9dHNH. Error bar represents mean ± SD, n = 17. Black curve shows fit to an exponential function. Time constant t (mean ± SE) is indicated in the plot. (D) Representative imaging views of the NTS digestion assay using dCas9 before and after adding 3′ to 5′ exonuclease. (E) Quantification of spot numbers per imaging view at different time points after adding 3′ to 5′ exonuclease in the NTS digestion assay using dCas9. Error bar represents mean ± SD, n = 17.

DNA Landing Assays Reveal Rapid HNH Conformational Fluctuations Coupled with TS Cleavage Activity in the Presence of Mg2+.

Next, we investigated the effects of TS cleavage on the conformation of the HNH domain by performing the DNA landing assay using Cas9LD750-dRuvC and Cas9LD750, the two Cas9 variants that have TS-cleaving activity (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Upon DNA binding, we again observed the transient low-FRET state followed by a transient high-FRET state for both Cas9LD750-dRuvC and Cas9LD750 (SI Appendix, Figs. S10A and S11A). Postcatalysis single-molecule FRET traces and histograms were obtained at 10 min after DNA binding (Fig. 4 A–F and SI Appendix, Figs. S10B and S11B). Different from Cas9LD750-dHNH and dCas9LD750, the FRET efficiency E for Cas9LD750-dRuvC rapidly fluctuated between E ∼ 0.38 and E ∼ 0.61 even to the time point by which 92% TS cleavage had occurred (Fig. 4 A–C and SI Appendix, Figs. S2D and S10B). Similar FRET fluctuations between E ∼ 0.38 and E ∼ 0.51 were observed for Cas9LD750 as well (Fig. 4 D–F and SI Appendix, Fig. S11B). Transition rates were calculated using vbFRET under the limited time resolution of our measurements (50 ms) (Fig. 4 B and E) (32). The E value difference between Cas9LD750 and Cas9LD750-dRuvC can be attributed to the fact that Cas9LD750 has NTS-cleaving activity but Cas9LD750-dRuvC does not (SI Appendix, Fig. S2D). A possible explanation would be that the NTS conformations in Cas9LD750-dRuvC and Cas9LD750 might be different due to the D10A mutation at the RuvC active site, which may further affect the HNH conformations because the NTS plays a key role in HNH conformations as predicted by molecular dynamics simulations (33). The E fluctuations were only observed for the TS-cleaving variants, Cas9LD750-dRuvC and Cas9LD750, not for the TS-noncleaving variants, Cas9LD750-dHNH and dCas9LD750, in the DNA landing assays (SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7). Considering that the cleaved TS remains hybridized with guide RNA, given its unambiguous density in the cryo-EM reconstruction (Fig. 1A) (26), the conformational plasticity of the postcatalytic HNH domain is responsible for the E fluctuations. We conclude that the post-TS-cleavage HNH domain possesses high flexibility. The high flexibility of the postcatalytic HNH domain also explains that the HNH domain was not visible in the product state cryo-EM reconstruction (Fig. 1A) (26).

Fig. 4.

Rapid conformational fluctuations coupled with TS cleavage activity. (A, Left) Schematic for Cas9LD750-dRuvC, which cleaves TS. (A, Right) Representative FRET trace from the DNA landing assay using Cas9LD750-dRuvC, acquired at 10 min after DNA binding to Cas9. The FRET efficiency trajectory (blue) was further idealized (red) using vbFRET (32). (B) Transition density plot from the DNA landing assay using Cas9LD750-dRuvC. The FRET transitions were identified from 100 single-molecule FRET traces acquired at 10 min after DNA binding using vbFRET. Transition rates between states are indicated in Fig. 4B, which were extracted from survival probability plots in SI Appendix, Fig. S12A. (C) FRET histogram from the DNA landing assay Cas9LD750-dRuvC, acquired at 10 min after DNA binding to Cas9. Green or red curve represents a fit to a single Gaussian peak. Blue curve represents a fit to double Gaussian peaks. (D, Left) Schematic for Cas9LD750, which cleaves both DNA strands. (D, Right) Representative FRET trace from the DNA landing assay using Cas9LD750, acquired at 10 min after DNA binding to Cas9. The FRET efficiency trajectory (blue) was further idealized (red) using vbFRET. (E) Transition density plot from the DNA landing assay using Cas9LD750. The FRET transitions were identified from 157 single-molecule FRET traces acquired at 10 min after DNA binding using vbFRET. Transition rates between states are indicated in Fig. 4E, which were extracted from survival probability plots in SI Appendix, Fig. S12B. (F) FRET histogram from the DNA landing assay Cas9LD750, acquired at 10 min after DNA binding to Cas9. Green or red curve represents a fit to a single Gaussian peak. Blue curve represents a fit to double Gaussian peaks. (G) Model for Cas9-mediated DNA cleavage. Cas9 is gray colored, except the HNH domain is yellow colored. Guide RNA, TS, and NTS are orange, blue, and light purple.

Discussion

In this work, we adopted two different schemes to immobilize the Cas9-RNA-DNA complex on a passivated slide, the DNA immobilization scheme (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Fig. S13A) and the extended tracrRNA immobilization scheme (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S13B). In the extended tracrRNA immobilization scheme, the DNA has a 20-nt ssDNA overhang as indicated in SI Appendix, Fig. S13B. The FRET histograms obtained from the two immobilization schemes were nearly identical (SI Appendix, Fig. S13), indicating that neither the immobilization schemes nor the 20-nt ssDNA affected the FRET values measured in this study.

We observed the E ∼ 0.83 state that is highly populated before DNA cleavage and completely depopulated after NTS cleavage in the EDTA-containing buffer (Fig. 1C). Similarly, the E ∼ 0.92 FRET state was observed in 15% single-molecule FRET traces a few seconds after DNA binding to Cas9LD750-dHNH RNP in the Mg2+-containing buffer (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 C and D), but it was rarely observed in the traces acquired at 10 min after DNA binding (only 1 trace out of 103 traces). Therefore, these two states with very high FRET values possibly represent precleavage HNH conformations that have not yet been characterized by previous cryo-EM or X-ray crystallography studies, and the E ∼ 0.92 FRET state is not obligatory for the majority of molecules. Of note, the higher Cy3-LD750 FRET value of the minority conformation does not necessarily mean a closer distance between the active site of the HNH domain and the scissile phosphate of TS because neither the active site of the HNH domain nor the scissile phosphate of TS is very close to the labeling positions, at least 1.4 nm away according to the structure of the Cas9-RNA-DNA complex (Protein Data Bank [PDB]: 6O0Y) (26).

A previous single-molecule FRET study using a different labeling configuration suggested that the HNH domain stably docks at a high-FRET (E ∼ 0.97) conformation (i.e., the docked conformation) after DNA cleavage (18). Because FRET is not sensitive to distance change at the range of around E ∼ 0.97 (34), relatively small conformational fluctuations would not be detectable. That the HNH domain was not visible in the product state cryo-EM reconstruction indicates the HNH domain does not remain in a steady conformation after cleaving both TS and NTS strands (Fig. 1A) (26), consistent with our observations in this study.

By comparing the FRET signals from Cas9LD750, Cas9LD750-dHNH, Cas9LD750-dRuvC, and dCas9LD750 in the DNA landing assays (Figs. 2 A–E and 4 A–F), we propose a model that the postcatalytic HNH conformations are coupled with TS and NTS cleavage activities (Fig. 4G): after the HNH domain activation, the docked conformation persists for catalytically dead Cas9. If NTS can be cleaved, the HNH domain will disengage from the docked conformation and can acquire an NTS-cleavage-competent conformation. If TS can be cleaved, the postcatalytic HNH domain possesses high flexibility.

Crystal and cryo-EM structures of wild-type Cas9 in complex with guide RNA and DNA failed to capture the PAM-distal region of NTS in electron density maps, suggesting a high degree of plasticity in the NTS (22, 26). Our data here and other studies are consistent with the model that the cleaved NTS is exposed to solvent for nucleic acid and protein binding (13, 15, 35, 36). We speculate that the 3′ flap of the cleaved NTS dissociates from the active site of the RuvC domain. During Cas9-mediated genome editing, the 3′ flap may be recognized as a single-stranded break, leading to the initiation of the DNA repair process. Therefore, although Cas9 RNP binds to both ends of cleaved DNA tightly, the DNA repair processes may start quickly at the Cas9 cleavage site.

We observed that a 3′-to-5′ ssDNA exonuclease efficiently invaded into the postcatalytic Cas9-RNA-DNA complex and digested the cleaved NTS (Fig. 3A). Our data indicate that if Cas9 cleaves the genomic DNA in a cell, any protein that acts on the 3′ end of ssDNA could be recruited to the Cas9 cleavage site through the exposed NTS. As such, it is likely that Cas9 can function as a programmable loader of ssDNA-targeting proteins to genomic DNA. We anticipate our work will facilitate both mechanistic studies and application developments of the CRISPR system.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Guide RNA and DNA Targets.

DNA oligonucleotides were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT). Cy3 or Cy5 N-hydroxysuccinimido (NHS) dyes were labeled on DNA through a thymine modified with an amine group through a C6 linker (IDT code:/iAmMC6T/). Higher than 90% labeling efficiency of DNA was confirmed by using the NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer. In the experiments using the DNA immobilization scheme (Fig. 1B), dsDNA targets were assembled by mixing the TS, NTS, and a 22-nt biotinylated adaptor strand (SI Appendix, Table S1) at 1:1.25:1 ratio in T50 buffer (10 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 8, 50 mM NaCl) and incubating at 95 °C for 1 min, then slowly cooling down to room temperature over 1 h. In the experiments using the extended tracrRNA immobilization scheme (Fig. 2A), the biotinylated adaptor strand was omitted in dsDNA targets. crRNA and tracrRNA were transcribed in vitro using the HiScribe T7 Quick High Yield RNA Synthesis Kit (NEB, E2050S). Wild-type guide RNA was annealed by mixing crRNA and tracrRNA at 1:1.25 ratio in Nuclease Free Duplex Buffer (IDT) and incubating at 95 °C for 1 min, then slowly cooling down to room temperature over 1 h. Biotinylated guide RNA was annealed by mixing crRNA and 3′ extended tracrRNA and 15-nt biotinylated adaptor annealing to the 3′ extended tracrRNA at 1:1:1 ratio in Nuclease Free Duplex Buffer (IDT) and incubating at 95 °C for 1 min, then slowly cooling down to room temperature over 1 h. The DNA and RNA sequences are listed in SI Appendix, Table S1.

Protein Preparation.

Wild-type Cas9 and dCas9 were gifts from Jennifer Doudna’s laboratory, University of California, Berkeley, CA. Cas9LD750 (C80S/C574S/E873C), Cas9LD750-dHNH (C80S/C574S/E873C/H840A), Cas9LD750-dRuvC (C80S/C574S/E873C/D10A), dCas9LD750 (C80S/C574S/E873C/D10A/H840A), and Cas9dHNH (H840A) were expressed and purified as previously described (30). See SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods for protein expression, purification, and labeling details.

Radio-Labeled Cleavage Assays.

Radioactive ATP γ-32P (PerkinElmer) along with T4 Polynucleotide Kinase (NEB, M0236S) was used to label the 5′ end of the target strand and/or nontarget strand. Cas9 and guide RNA were mixed to a final concentration of 300 nM and 100 nM, respectively, in reaction buffer (20 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 8, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5% (vol/vol) glycerol and 0.2 mg/mL bovine serum albumin [BSA]) at room temperature for 10 min. In SI Appendix, Figs. S2C and S9A, the reaction buffer was supplied with saturated Trolox (>5 mM), 0.8% (wt/vol) dextrose, 1 mg/mL glucose oxidase, and 0.04 mg/mL catalase. The radiolabeled DNA targets were then added to the mixture to a final concentration of 1 nM. Time courses were started at this point, upon addition of the DNA. At indicated times, reactions were terminated by mixing thoroughly with 2× volume of phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol 25:24:1 (Sigma-Aldrich, P3803). The supernatant was collected and mixed with 5× volume of formamide loading buffer (95% formamide, 5 mM EDTA, 0.025% (wt/vol) bromophenol blue, 0.025% (wt/vol) xylene cyanol). Samples were then resolved using Tris/borate/EDTA (TBE) polyacrylamide gels containing 15% acrylamide (19:1) and 50% (wt/vol) urea. Gels were imaged via PhosphorImager (GE Healthcare) and quantified using Image Gauge or ImageJ/Fiji (37).

Microscopy and Data Acquisition for Single-Molecule Assays.

Microscopy was performed on a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope with a custom prism type total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFM) module and Nikon 60×/1.27 NA objective (CFI Plan Apo IR 60XC WI). Solid-state lasers (Coherent, 641 nm; Shanghai Dream Lasers Technology, 543 and 750 nm) were combined and coupled to an optical fiber for illumination. Emission signals was filtered using long-pass filters (T540LPXR UF3, T635LPXR UF3, and T760LPXR UF3) and a custom laser-blocking notch filter (ZET488/543/638/750M) from Chroma. Imaging movies were recorded at 20 Hz unless indicated using an electron-multiplying charge-coupled device (EMCCD; Andor iXon 897). The microscopy system was driven using smCamera 2.0.

Single-Molecule Data Analysis.

The FRET histograms and traces were extracted from single-molecule imaging movies using custom-written scripts, as described previously (30). A γ-correction factor (γ = 1/6) was used in the FRET data to account for the differences in quantum yield and detection efficiency between Cy3 and LD750 (34). The first five frames of each molecule’s FRET efficiency time traces were used as data points to calculate the FRET histograms. More than 800 molecules were measured to obtain each FRET histogram. To obtain the survival probability plots in SI Appendix, Fig. S12, at least 100 single-molecule FRET traces were analyzed using vbFRET (32). Transition density plots were also generated using the FRET transitions identified by vbFRET. For other survival probability plots, lifetimes of interest were measured manually from individual single-molecule traces using custom-written scripts. The custom-written scripts are available at GitHub (https://github.com/ywang285/smFRET_code).

Single-Molecule FRET Assay.

For the single-molecule FRET assay in Fig. 1B, Cas9 RNP was assembled by mixing 200 nM Cas9 and 200 nM wild-type guide RNA in the Mg2+-containing buffer (20 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 8, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5% [vol/vol] glycerol, 0.2 mg/mL BSA, and saturated Trolox (>5 mM), 0.8% (wt/vol) dextrose), incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The Cas9 RNP was diluted to 40 nM using a EDTA-containing buffer (20 mM Tris⋅HCl, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM EDTA, 5% [vol/vol] glycerol, 0.2 mg/mL BSA, and saturated Trolox [>5 mM]), incubated for 10 min at room temperature. A total of 1 nM on-target dsDNA with Cy3 and biotin was then added to the mixture and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. The assembled Cas9-RNA-DNA ternary complex was diluted to 25 pM in the EDTA-containing buffer supplied with GLOXY (1 mg/mL glucose oxidase, 0.04 mg/mL catalase) and immobilized on the polyethylene glycol (PEG)-passivated flow chamber surface (Johns Hopkins University Slide Production Core for Microscopy) using NeutrAvidin-biotin interaction. The chamber was washed with the EDTA-containing buffer supplied with GLOXY to remove free Cas9-RNA-DNA ternary complex. With 543-nm laser excitation, the precleavage FRET histograms of Cy3 and LD750 colocalized spots were measured (Fig. 1C, Top row). Then the chamber was washed with Mg2+-containing buffer (20 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 8, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5% [vol/vol] glycerol, 0.2 mg/mL BSA and saturated Trolox [>5 mM], 0.8% [wt/vol] dextrose) supplied with GLOXY, incubated for 10 min at room temperature, then washed with EDTA-containing buffer. The postcleavage FRET histograms of Cy3 and LD750 colocalized spots were measured (Fig. 1C, Bottom row).

For the DNA landing assay in Figs. 2 A–E and 4 A–D, Cas9 RNP was assembled by mixing 200 nM Cas9 and 100 nM biotinylated guide RNA in the Mg2+-containing buffer and incubating at room temperature for 10 min. The Cas9 RNP was diluted to 150 pM using the Mg2+-containing buffer supplied with GLOXY and immobilized on the PEG-passivated flow chamber surface using NeutrAvidin-biotin interaction. The chamber was washed with the Mg2+-containing buffer supplied with GLOXY. To obtain the real-time FRET traces of the DNA landing assay, the movie acquisition started at 20 Hz with 543-nm laser excitation, and 5 nM on-target dsDNA with Cy3 were flowed into the chamber in the Mg2+-buffer supplied with GLOXY at 10 s after the start of movie acquisition. After ∼150 s, the movie acquisition stopped, and laser was turned off. At 10 min after flowing in the on-target dsDNA target, the FRET histograms of Cy3 and LD750 colocalized spots were measured.

For the Cas9 binding assay in SI Appendix, Fig. S9B, 50 pM on-target dsDNA with Cy3 and biotin in the Mg2+-containing buffer was immobilized on the PEG-passivated flow chamber surface using NeutrAvidin-biotin interaction. A total of 100 nM Cas9 RNP was assembled by mixing 300 nM Cas9LD750-dHNH and 100 nM wild-type guide RNA in the Mg2+-containing buffer and incubating at room temperature for 10 min. The Cas9 RNP was diluted to the concentrations indicated in SI Appendix, Fig. S9D using the Mg2+-containing buffer supplied with GLOXY. The movie acquisition started at 5 Hz with 543-nm laser excitation and the Cas9 RNP was flowed into the chamber in the Mg2+-containing buffer supplied with GLOXY at ∼10 s after the start of the movie acquisition.

For the comparison of two different immobilization schemes in SI Appendix, Fig. S13, the Cas9-RNA-DNA was assembled and immobilized to the quartz surface in the Mg2+-containing buffer supplied with GLOXY and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Then FRET histograms of Cy3 and LD750 colocalized spots were measured for different Cas9 variants.

NTS Digestion Assay.

On-target dsDNA with Cy5 was immobilized on the PEG-passivated flow chamber surface using NeutrAvidin-biotin interaction. A total of 100 nM Cas9 RNP was assembled by mixing 125 nM Cas9 and 100 nM wild-type guide RNA and incubating for 10 min at room temperature in the Mg2+-containing buffer supplied with GLOXY. The Cas9 RNP was flowed into the DNA-immobilized chamber and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. Free Cas9 RNP was flushed out using the Mg2+-containing buffer supplied with GLOXY. Next, short movies of 10 frames at 10 Hz with 641-nm laser excitation were taken at 17 different fields of view. The first 5 frames of each movie were averaged and Cy5 spot number per imaging view was measured as 0-min data (Fig. 3 C and E). A total of 0.2 U/μL DNA Polymerase I, large (Klenow) fragment (NEB, M0210S) supplied with the deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) mix (33 μM each) in the Mg2+-containing buffer supplied with GLOXY was added to the flow chamber. Cy5 spot number per imaging view was measured at 2.5 min, 7.5 min, and 15 min time points after the addition of the Klenow fragment (Fig. 3 C and E).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Doudna laboratory (University of California, Berkeley) for generously providing wild-type Cas9 and dCas9 stocks. The project was supported by grants from the NIH (GM122569 to T.H. and GM097330 to S.B) and the NSF (PHY-1430124 to T.H.). T.H. is an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. K.C. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2010650118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

Custom-written scripts for smFRET data analysis are available at GitHub (https://github.com/ywang285/smFRET_code). All other data and details about materials used are present in the article and SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Marraffini L. A., Sontheimer E. J., CRISPR interference: RNA-directed adaptive immunity in bacteria and archaea. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 181–190 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cong L., et al. , Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339, 819–823 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doudna J. A., Charpentier E., Genome editing. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 346, 1258096 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mali P., et al. , RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science 339, 823–826 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu P. D., Lander E. S., Zhang F., Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering. Cell 157, 1262–1278 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang F., Doudna J. A., CRISPR-Cas9 structures and mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 46, 505–529 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jinek M., et al. , A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337, 816–821 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh D., Sternberg S. H., Fei J., Doudna J. A., Ha T., Real-time observation of DNA recognition and rejection by the RNA-guided endonuclease Cas9. Nat. Commun. 7, 12778 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sternberg S. H., Redding S., Jinek M., Greene E. C., Doudna J. A., DNA interrogation by the CRISPR RNA-guided endonuclease Cas9. Nature 507, 62–67 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szczelkun M. D., et al. , Direct observation of R-loop formation by single RNA-guided Cas9 and Cascade effector complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 9798–9803 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gong S., Yu H. H., Johnson K. A., Taylor D. W., DNA unwinding is the primary determinant of CRISPR-Cas9 activity. Cell Rep. 22, 359–371 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ran F. A., et al. , Double nicking by RNA-guided CRISPR Cas9 for enhanced genome editing specificity. Cell 154, 1380–1389 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anzalone A. V., et al. , Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature 576, 149–157 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anzalone A. V., Koblan L. W., Liu D. R., Genome editing with CRISPR-Cas nucleases, base editors, transposases and prime editors. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 824–844 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richardson C. D., Ray G. J., DeWitt M. A., Curie G. L., Corn J. E., Enhancing homology-directed genome editing by catalytically active and inactive CRISPR-Cas9 using asymmetric donor DNA. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 339–344 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newton M. D., et al. , DNA stretching induces Cas9 off-target activity. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 26, 185–192 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sternberg S. H., LaFrance B., Kaplan M., Doudna J. A., Conformational control of DNA target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas9. Nature 527, 110–113 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dagdas Y. S., Chen J. S., Sternberg S. H., Doudna J. A., Yildiz A., A conformational checkpoint between DNA binding and cleavage by CRISPR-Cas9. Sci. Adv. 3, eaao0027 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang M., et al. , The conformational dynamics of Cas9 governing DNA cleavage are revealed by single-molecule FRET. Cell Rep. 22, 372–382 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osuka S., et al. , Real-time observation of flexible domain movements in CRISPR-Cas9. EMBO J. 37, e96941 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anders C., Niewoehner O., Duerst A., Jinek M., Structural basis of PAM-dependent target DNA recognition by the Cas9 endonuclease. Nature 513, 569–573 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang F., et al. , Structures of a CRISPR-Cas9 R-loop complex primed for DNA cleavage. Science 351, 867–871 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huai C., et al. , Structural insights into DNA cleavage activation of CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat. Commun. 8, 1375 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang F., Zhou K., Ma L., Gressel S., Doudna J. A., STRUCTURAL BIOLOGY. A Cas9-guide RNA complex preorganized for target DNA recognition. Science 348, 1477–1481 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen J. S., et al. , Enhanced proofreading governs CRISPR-Cas9 targeting accuracy. Nature 550, 407–410 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu X., et al. , Cryo-EM structures reveal coordinated domain motions that govern DNA cleavage by Cas9. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 26, 679–685 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee S., Lee J., Hohng S., Single-molecule three-color FRET with both negligible spectral overlap and long observation time. PLoS One 5, e12270 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shibata M., et al. , Real-space and real-time dynamics of CRISPR-Cas9 visualized by high-speed atomic force microscopy. Nat. Commun. 8, 1430 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sung K., Park J., Kim Y., Lee N. K., Kim S. K., Target specificity of Cas9 nuclease via DNA rearrangement regulated by the REC2 domain. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 7778–7781 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh D., et al. , Mechanisms of improved specificity of engineered Cas9s revealed by single-molecule FRET analysis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 25, 347–354 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okafor I. C., et al. , Single molecule analysis of effects of non-canonical guide RNAs and specificity-enhancing mutations on Cas9-induced DNA unwinding. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 11880–11888 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bronson J. E., Fei J., Hofman J. M., Gonzalez R. L. Jr, Wiggins C. H., Learning rates and states from biophysical time series: A Bayesian approach to model selection and single-molecule FRET data. Biophys. J. 97, 3196–3205 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palermo G., Miao Y., Walker R. C., Jinek M., McCammon J. A., Striking plasticity of CRISPR-Cas9 and key role of non-target DNA, as revealed by molecular simulations. ACS Cent. Sci. 2, 756–763 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roy R., Hohng S., Ha T., A practical guide to single-molecule FRET. Nat. Methods 5, 507–516 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rees H. A., Liu D. R., Base editing: Precision chemistry on the genome and transcriptome of living cells. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19, 770–788 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou W., et al. , A CRISPR-Cas9-triggered strand displacement amplification method for ultrasensitive DNA detection. Nat. Commun. 9, 5012 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneider C. A., Rasband W. S., Eliceiri K. W., NIH image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Custom-written scripts for smFRET data analysis are available at GitHub (https://github.com/ywang285/smFRET_code). All other data and details about materials used are present in the article and SI Appendix.