Abstract

BACKGROUND

Cholecystoduodenal fistula is a rare complication of cholelithiasis. Symptoms are usually non-specific and often indistinguishable from those of etiologic diseases, but it rarely presents as severe gastrointestinal bleeding. Bleeding associated with cholecystoduodenal fistula usually requires surgery because significant bleeding from the cystic artery is unlikely to be resolved by conservative management or endoscopic hemostasis.

CASE SUMMARY

We report a case of cholecystoduodenal fistula that presented with hematemesis which was diagnosed by endoscopy and computed tomography. Endoscopic hemostasis could not be achieved, but surgical treatment was successful. Additionally, we have presented a literature review.

CONCLUSION

Cholecystoduodenal fistula should be considered as differential diagnosis when a patient with history of gallstone disease presents with gastrointestinal bleeding.

Keywords: Biliary fistula, Hematemesis, Cholecystitis, Gallstones, Cholecystectomy, Case report

Core Tip: Cholecystoenteric fistula, an abnormal communication from gallbladder to the gastrointestinal tract, is a rare complication of cholelithiasis. It is a type of internal biliary fistula that occurs secondary to cholelithiasis in more than 90% of cases. The clinical presentation of cholecystoenteric fistula is variable, and a preoperative diagnosis is achieved rarely, while gastrointestinal bleeding as its initial presentation is also rare. Here, we report a case of cholecystoduodenal fistula that presented with hypovolemic shock due to massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

INTRODUCTION

Cholecystoenteric fistula, an abnormal communication between gallbladder and the gastrointestinal tract, is a rare complication of cholelithiasis. It is a type of internal biliary fistula that occurs as complication of cholelithiasis in more than 90% of cases[1]. The cholecystoenteric fistula presents in variable symptoms, and an accurate diagnosis prior to surgery is achieved rarely[2]. It also rarely presents as upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Here, we report a case of cholecystoduodenal fistula that presented with hypovolemic shock due to massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

An 88-year-old male visited our emergency room complaining of right upper quadrant abdominal pain, and nausea.

History of present illness

The pain started 3 d ago, which was continuous cramping pain aggravated by meal, and severity of pain had increased from numeric rating scale of 3 to 8. The patient denied fevers, diarrhea or jaundice. Upon visit to the emergency room his blood pressure and heart rate were normal, but body temperature was elevated to 38 ºC.

History of past illness

His past medical record showed that he was diagnosed with hypertension, diabetes, heart failure, chronic kidney disease, previous cerebrovascular accident, and was currently taking aspirin. Also, computed tomography of abdomen taken 2 years ago showed that he had multiple stones in gall bladder without wall thickening, and he had no history of recurrent abdominal pain.

Personal and family history

He was an ex-smoker who had quit smoking 20 years ago, and no notable family history was found.

Physical examination

Physical examination revealed tenderness at right upper quadrant and positive murphy sign.

Laboratory examinations

Initial laboratory findings were as follows; white blood cells 6200/mm3, hemoglobin 134 g/L, aspartate aminotransferase 213 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase 164 IU/L, and C-reactive protein 14.3 mg/L.

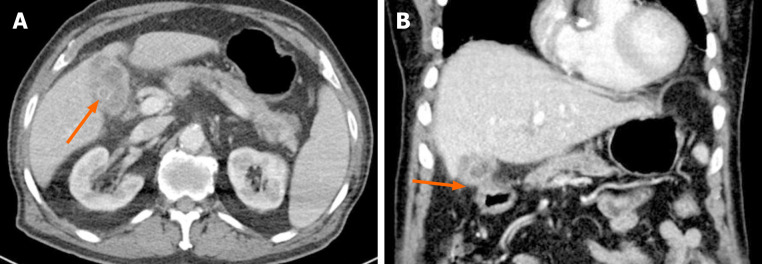

Imaging examinations

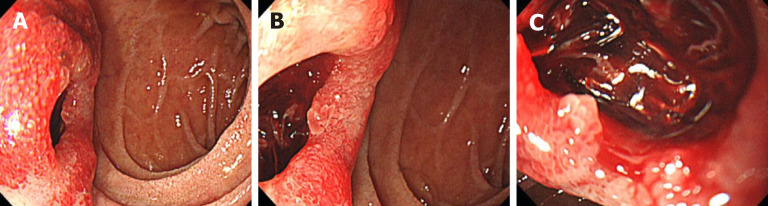

Based on past medical record and current findings, abdominal computed tomography was done which revealed a gallstone and asymmetric gallbladder wall thickening, suggestive of chronic cholecystitis (Figure 1). Once he returned to the emergency department, he suddenly complained of hematemesis and developed hypovolemic shock (blood pressure 82/50 mmHg, heart rate 100/min). Emergent esopha-gogastroduodenoscopy was done, and bleeding was suspected at the duodenal bulb. However, it was difficult to make a definite diagnosis due to poor visibility. Endoscopy was performed the following day, after his condition had stabilized, and revealed an opening at the anterior wall of the duodenal bulb filled with blood clot suggestive of bleeding from cholecystoduodenal fistula (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Radiologic images. A: Computed tomography revealed a gallstone (arrow) and a non-dilated gallbladder with wall thickening, suggestive of chronic cholecystitis; B: The gallbladder was adherent to duodenum in coronal view.

Figure 2.

Endoscopic images. A: Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed an opening at the anterior wall of the duodenal bulb; B: Closer image of duodenal bulb; C: The opening was filled with a blood clot, suggestive of bleeding from cholecystoduodenal fistula.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Final diagnosis was cholecystitis with cholecystoduodenal fistula.

TREATMENT

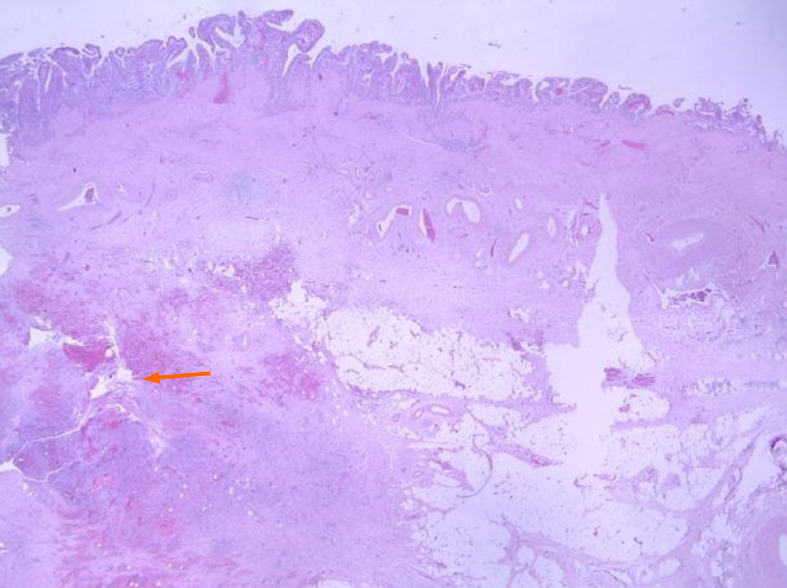

Once the diagnosis was made he underwent open cholecystectomy and fistula closure. Operative findings and pathologic examination confirmed chronic cholecystitis with cholecystoduodenal fistula (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Pathologic image of resected gallbladder. Microscopy shows the fistula in the lower portion of gallbladder mucosa (arrow, hematoxylin & eosin stain, × 15).

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

After surgery, his aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase had improved to 16 IU/L and 75 IU/L respectively. His postoperative course was uneventful with the exception of wound dehiscence, which was improved by simple dressing and suture placement. He was discharged 16 d after the operation and was followed uneventfully for 18 mo.

DISCUSSION

Most internal biliary fistulas develop spontaneously, while majority of external fistulas develop as an iatrogenic event following surgery or percutaneous interventional procedures. About 91%-94% of spontaneous internal biliary fistulas are caused by stone in the biliary tract[1], followed by peptic ulcer disease as the second most common cause. Tumors, biliary abscesses, and echinococcus cysts have also been reported as other causes of internal biliary fistula[3]. Cholecystoenteric fistula is a rare complication of gallstone disease with an autopsy reported incidence of 0.1%-0.5% and an incidence of 1.2%-5% among cholecystectomy cases[4]. The condition occurs predominantly in women around the age of 60 years[4,5]. The most common type of cholecystoenteric fistula is the cholecystoduodenal type, followed by cholecystocolonic and cholecystogastric fistula[1].

The pathogenesis of cholecystoduodenal fistula is unclear, but cholecystoenteric fistula occurring as late complications of gallstone disease is also known as Mirizzi syndrome type V[6]. Pathophysiology for such complication is explained by mechanical pressure of gallstone that causes erosion of gallbladder and common bile duct wall that eventually results in formation of cholecystobiliary fistula[7,8]. Recurrent episodes of gallbladder inflammation can also create fistula tract with other sites such as cholecystoduodenal, cholecystogastric, and cholecystocolonic fistulas[9,10].

In general, there are no specific clinical symptoms or signs suggestive of internal biliary fistula. Its symptoms are often indistinguishable from those of etiologic diseases, including abdominal pain, cholangitis with fever and/or jaundice, gallstone ileus, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, as well as acute or chronic/recurrent pancreatitis[1].

Cholecystoduodenal fistula rarely causes gastrointestinal bleeding. Invasion of the cystic artery by a duodenal ulcer may cause massive bleeding, and a gallstone can cause erosion of the same artery[4]. Reports on cholecystoduodenal fistula as a cause of severe upper gastrointestinal bleeding are rare. A thorough search of the medical literature revealed only 11 case reports published in English (Table 1)[3-5,11-18]. Among these reported cases, men were slightly more affected than women and two thirds were older than 60 years. Gallstone was the most common cause, and peptic ulcer was the etiology in only two cases. Endoscopic findings were variable and ranged from ulcer, fistulous opening, and bleeding of unknown origin. A subepithelial lesion was suspected in two cases[5,14]. Endoscopic hemostasis was attempted in four cases, but surgery was finally required in all cases[3,4,11,17]. All 13 patients that underwent surgery had good outcomes. Conservative treatment was administered to two patients and one patient expired. At autopsy, bleeding was determined to be from the cystic artery by cholecystoduodenal fistula[18].

Table 1.

Previous cases that presented with upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to a cholecystoduodenal fistula

|

Study

|

Gender/age

|

Etiology

|

Endoscopic finding

|

Treatment

|

Clinical course

|

| Corry et al[12] | F/81 | Gallstone | Not performed | Operation | Recovered |

| F/80 | Gallstone | Not performed | Operation | Recovered | |

| Schenken et a [18] | M/97 | Gallstone | Not performed | Conservative | Expired |

| Hjelmqvist et al[14] | M/54 | Gallstone | Ulcer | Operation | Recovered |

| F/86 | Gallstone | Ulcer | Operation | Recovered | |

| F/53 | Gallstone | Subepithelial lesion | Operation | Recovered | |

| Kochhar et al[15] | M/24 | Peptic ulcer | Not diagnostic (duodenal bleeding) | Operation | Recovered |

| Lee et al[4] | M/60 | Acalculous cholecystitis | Ulcer | Endoscopic hemostasis, operation | Recovered |

| Changku et al[11] | M/50 | Gallstone | Ulcer | Endoscopic hemostasis, angiography and embolization, operation | Recovered |

| Kosugi et al[16] | F/66 | Gallstone | Not diagnostic (old blood) | Operation | Recovered |

| Mohammed et al[17] | F/44 | Gallstone | Fistulous opening | Endoscopic hemostasis, operation | |

| Fefeman et al[13] | M/86 | Gallstone | Ulcer and fistulous opening | Operation | Recovered |

| Kohli et al[5] | M/82 | Gallstone | Subepithelial lesion | Conservative | Recovered |

| Vadioaloo et al[3] | M/70 | Peptic ulcer | Ulcer | Endoscopic hemostasis, operation | Recovered |

| Present case | M/88 | Gallstone | Fistulous opening | Operation | Recovered |

As cholecystoduodenal fistula is a rare cause of massive gastrointestinal bleeding, clinicians should be aware of some signs that may help in differential diagnosis. Thorough history taking is always essential as history of gallstone disease may help in considering cholecystoduodenal fistula as differential diagnosis. It has been suggested by many authors that pneumobilia, a small atrophic gallbladder adherent to the neighboring organs, and a history of jaundice may be indicators for presence of a cholecystoenteric fistula[3,4,17]. Nonvisualization of the gallbladder, despite absent history of cholecystectomy, or the presence of a thick-walled shrunken gallbladder adherent to the neighboring organs, have been reported as a suggestive finding of internal biliary fistula, especially the cholecystoenteric type.

Once the diagnosis is made, surgical treatment is the most effective method of treatment. Although many fistulas are treated with laparoscopic method due to increased skill of the surgeons and advanced techniques, open operation is preferred when there is distortion of anatomy and severe inflammation[19]. The patient in this case report received open operation due to severe inflammation. Angioembolization is another treatment to consider at available centers for identification and possible blockage of active bleeding from fistula that could not be controlled by endoscopic hemostasis. However, most fistulas are difficult to close up if recurrent cholecystitis is not controlled[11], and surgical management is usually required.

CONCLUSION

In summary, gastrointestinal bleeding caused by cholecystoduodenal fistula usually requires surgery because significant bleeding from the cystic artery is unlikely to be resolved by conservative management or endoscopic hemostasis[3]. Reported outcomes after surgery are excellent. A high index of suspicion is necessary, and early diagnosis of cholecystoduodenal fistula is essential for successful treatment.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement: Authors declare no conflict of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: October 5, 2020

First decision: October 27, 2020

Article in press: December 11, 2020

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Wang SY S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang YL

Contributor Information

Jin Myung Park, Department of Internal Medicine, Kangwon National University School of Medicine, Chuncheon 24289, Kangwon Do, South Korea; Department of Gastroenterology, Kangwon National University Hospital, Chuncheon 24289, Kangwon Do, South Korea.

Chang Don Kang, Department of Internal Medicine, Kangwon National University School of Medicine, Chuncheon 24289, Kangwon Do, South Korea; Department of Gastroenterology, Kangwon National University Hospital, Chuncheon 24289, Kangwon Do, South Korea. kcdcejhw@kangwon.ac.kr.

Ji Hyun Kim, Department of Internal Medicine, Kangwon National University School of Medicine, Chuncheon 24289, Kangwon Do, South Korea; Department of Gastroenterology, Kangwon National University Hospital, Chuncheon 24289, Kangwon Do, South Korea.

Sang Hoon Lee, Department of Internal Medicine, Kangwon National University School of Medicine, Chuncheon 24289, Kangwon Do, South Korea; Department of Gastroenterology, Kangwon National University Hospital, Chuncheon 24289, Kangwon Do, South Korea.

Seung-Joo Nam, Department of Internal Medicine, Kangwon National University School of Medicine, Chuncheon 24289, Kangwon Do, South Korea; Department of Gastroenterology, Kangwon National University Hospital, Chuncheon 24289, Kangwon Do, South Korea.

Sung Chul Park, Department of Internal Medicine, Kangwon National University School of Medicine, Chuncheon 24289, Kangwon Do, South Korea; Department of Gastroenterology, Kangwon National University Hospital, Chuncheon 24289, Kangwon Do, South Korea.

Sung Joon Lee, Department of Internal Medicine, Kangwon National University School of Medicine, Chuncheon 24289, Kangwon Do, South Korea; Department of Gastroenterology, Kangwon National University Hospital, Chuncheon 24289, Kangwon Do, South Korea.

Seungkoo Lee, Anatomy and Pathology, Kangwon National University School of Medicine, Chuncheon 200947, Kangwon Do, South Korea; Department of Pathology, Kangwon National University Hospital, Chuncheon 24289, Kangwon Do, South Korea.

References

- 1.Inal M, Oguz M, Aksungur E, Soyupak S, Börüban S, Akgül E. Biliary-enteric fistulas: report of five cases and review of the literature. Eur Radiol. 1999;9:1145–1151. doi: 10.1007/s003300050810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crespi M, Montecamozzo G, Foschi D. Diagnosis and Treatment of Biliary Fistulas in the Laparoscopic Era. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:6293538. doi: 10.1155/2016/6293538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vadioaloo DK, Loo GH, Leow VM, Subramaniam M. Massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a rare complication of cholecystoduodenal fistula. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-228654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SB, Ryu KH, Ryu JK, Kim HJ, Lee JK, Jeong HS, Bae JS. Acute acalculous cholecystitis associated with cholecystoduodenal fistula and duodenal bleeding. A case report. Korean J Intern Med. 2003;18:109–114. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2003.18.2.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kohli DR, Anis M, Shah T. Cholecystoenteric Fistula Masquerading as a Bleeding Subepithelial Mass. ACG Case Rep J. 2017;4:e125. doi: 10.14309/crj.2017.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beltran MA, Csendes A, Cruces KS. The relationship of Mirizzi syndrome and cholecystoenteric fistula: validation of a modified classification. World J Surg. 2008;32:2237–2243. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9660-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Csendes A, Díaz JC, Burdiles P, Maluenda F, Nava O. Mirizzi syndrome and cholecystobiliary fistula: a unifying classification. Br J Surg. 1989;76:1139–1143. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800761110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raiford TS. Intestinal obstruction due to gallstones. (Gallstone ileus) Ann Surg. 1961;153:830–838. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196106000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glenn F, Reed C, Grafe WR. Biliary enteric fistula. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1981;153:527–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beltran MA, Csendes A. Mirizzi syndrome and gallstone ileus: an unusual presentation of gallstone disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:686–689. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Changku J, Shaohua S, Zhicheng Z, Shusen Z. Upper gastric tract bleeding due to cholecystoduodenal fistula: a case report. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:1372–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corry RJ, Mundth ED, Bartlett MK. Massive upper-gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage. A complication of cholecystoduodenal fistula. Arch Surg. 1968;97:531–532. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1968.01340040027001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feferman Y, Bard V, Aviran N, Stein M, Kashtan H, Sadot E. An Unusual Presentation of Cholecystoduodenal Fistula: Massive Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. J Gastrointest Dig Syst. 2015;5:314. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hjelmqvist B, Borgström A, Zederfeldt B. Major gastrointestinal haemorrhage as a complication of cholecystoduodenal fistula in gallstone disease. Report of three cases. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1985;74:6–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kochhar R, Krishna PR, Gupta NM, Mehta SK. Massive gastrointestinal bleeding due to cholecystoduodenal fistula. Case report. Acta Chir Scand. 1988;154:471–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kosugi S, Tani T, Kurosaki I, Hatakeyama K. Gallstone ileus with cholecystoduodenal fistula presenting massive upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:624–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohammed N, Godfrey EM, Subramanian V. Cholecysto-duodenal fistula as the source of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2013;45 Suppl 2 UCTN:E250–E251. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schenken JR, Adamson JR. Fatal gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage: a complication of ulcerative cholecystitis, cholelithiasis, and cholecystoduodenal fistula. Am J Clin Pathol. 1970;53:423–424. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/53.3.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esparza Monzavi CA, Peters X, Spaggiari M. Cholecystocolonic fistula: A rare case report of Mirizzi syndrome. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2019;63:97–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2019.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]