Abstract

PURPOSE:

To investigate the efficacy and safety of illuminated microcatheter-assisted trabeculotomy as a secondary procedure in patients with primary congenital glaucoma (PCG).

METHODS:

This retrospective case series included patients with PCG who underwent trabeculotomy using an illuminated microcatheter with the intent of catheterizing the full circumference of Schlemm's canal in a single procedure. Success was defined as intraocular pressure (IOP) ≤21 mmHg, with or without the use of glaucoma medications. Clinical examination data were collected for up to 36 months postoperatively.

RESULTS:

Surgery was performed on 16 eyes of 16 patients. The mean patient age was 75.1 ± 69.4 months (range: 4.0–216.0 months). Complete catheterization was achieved in 11 of the 16 eyes (69%), whereas partial catheterization was achieved in five of the 16 eyes (31%). All eyes had previously undergone surgery for PCG. The mean follow-up duration was 20.3 ± 9.0 months (range, 12.0–36.0 months). IOP was reduced from a mean of 31.8 ± 6.6 mmHg preoperatively to 15.6 ± 3.7 mmHg at the final follow-up (P < 0.001). The mean preoperative number of glaucoma medications was 3.9 ± 0.5, which was reduced to 1.1 ± 1.6 at the final follow-up (P = 0.001). Ten (62.5%) of the 16 eyes did not require glaucoma medication by the final follow-up. Early transient postoperative hyphema occurred in six eyes (37.5%). No other complications were noted. All corneas were clear at the final follow-up.

CONCLUSION:

Ab externo circumferential trabeculotomy using an illuminated microcatheter may be safe and effective as a secondary surgical option for children with PCG after unsuccessful glaucoma surgery.

Keywords: 360°, childhood glaucoma, illuminated microcatheter, primary congenital glaucoma, Schlemm's canal, trabeculotomy

Introduction

Primary congenital glaucoma (PCG) is a major cause of childhood blindness in developing countries, especially in the Middle-East region.[1,2] It presumably involves a developmental abnormality in the trabecular meshwork, which impairs aqueous humor outflow.[3] While medical management is used as temporary therapy, surgery constitutes the definitive treatment.[4]

Angle surgery (goniotomy or trabeculotomy ab externo) is the primary treatment for PCG. Goniotomy is suitable when corneal clarity enables angle visualization. Otherwise, trabeculotomy ab externo is preferred.[5] Multiple attempts may be needed to achieve target intraocular pressure (IOP).[5,6] To address these limitations, a 6-0 polypropylene suture has been used for 360° trabeculotomy.[7] However, suture misdirection may occur.[8] Illuminated microcatheter-assisted circumferential trabeculotomy (MAT) may facilitate catheter tip tracking during surgery. This avoids catheter misdirection, particularly in patients with poor corneal clarity.[9] This study evaluated the effectiveness and safety of illuminated MAT in patients with PCG for whom glaucoma surgery had been unsuccessful.

Methods

Patients

This retrospective case series included 16 eyes from 16 patients who underwent MAT following unsuccessful glaucoma surgery at the King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital (KKESH; Riyadh, Saudi Arabia). Previous unsuccessful surgeries included filtering surgery or conventional trabeculotomies. All patients included in this study demonstrated the signs consistent with a diagnosis of PCG such as elevated IOP, corneal edema, glaucomatous cupping of the optic nerve, increased axial length, or increased corneal diameter. They had no other systemic or ocular abnormalities. Patients were excluded if they exhibited more than 180° of peripheral anterior synechiae. Patients were also excluded if they had previously undergone ophthalmic surgeries other than glaucoma surgery. All patients were followed up for at least 12 months. Approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of KKESH for this study protocol. The present study was carried out in accordance with the tenets of the declaration of Helsinki. The review board waived the requirement for consent due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Data collection

Detailed patient histories and clinical data were gathered from the medical records. Clinical examinations (conducted under general anesthesia or sedation) included the following components: IOP measurement, slit-lamp examination, gonioscopy, and optic disc assessment. IOP was measured using a Tonopen Avia (Reichert Technologies, Depew, NY, USA), pneumotonometer (Reichert Technologies, Depew), or iCare Pro tonometer (iCare, Vantaa, Finland). Data were collected from all procedures carried out at 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, and 36 months postoperatively. Operative reports were investigated to determine the extent of trabeculotomy. A 360° procedure was regarded as complete trabeculotomy, while a < 360° procedure was considered partial trabeculotomy. The following criteria were used to determine success rate and stability after the surgery: success comprised IOP ≤ 21 mmHg, with or without the use of glaucoma medications. Stability was defined as a stable postoperative cup-to-disc ratio (within 0.1 of the value recorded at the preoperative examination), combined with the absence of a requirement for additional glaucoma surgery.

The following data were collected from the medical records of postoperative assessments: visual acuity, IOP, number of glaucoma medications, cup-to-disc ratio, slit-lamp examination findings, and any complications. The safety of the procedure was determined on the basis of incidence and severity of complications that occurred either intraoperatively or postoperatively.

Surgical technique

Details regarding the surgical technique were gathered from the operative reports. All surgeries were conducted by a single surgeon (I.J.), whereas the patients were under general anesthesia. The eye was rotated inferiorly, following superior placement of a clear corneal traction suture (#7-0 Vicryl). To avoid regions with potential damage to Schlemm's canal caused by previous surgeries, a fornix-based conjunctival flap was created lateral to any existing flap (or bleb). A superficial scleral flap (4 mm × 4 mm) was raised. Filter papers pre-soaked in mitomycin C solution (0.2 mg/ml) were then applied to the region under and around the scleral flap for 3 min. Upon removal of the filter papers, irrigation with saline was performed. To detect and deroof Schlemm's canal, another deep scleral flap (3 mm × 3 mm) was created using a diamond blade. This second flap constituted nearly complete scleral thickness beneath the first flap. Subsequently, a temporal paracentesis was created and viscoelastic was injected into the anterior chamber.

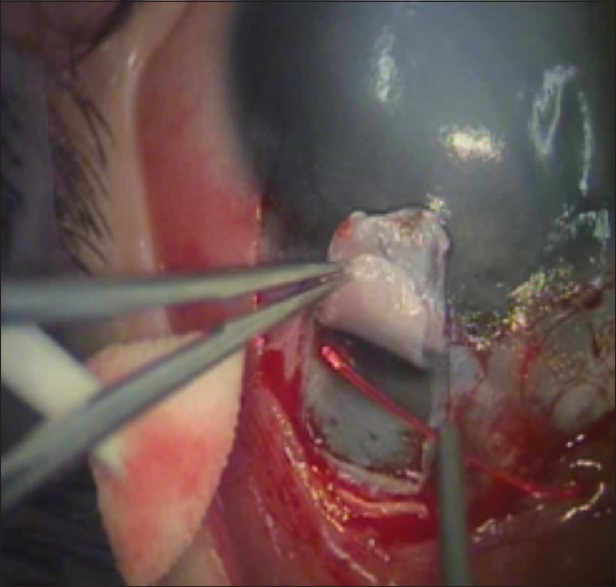

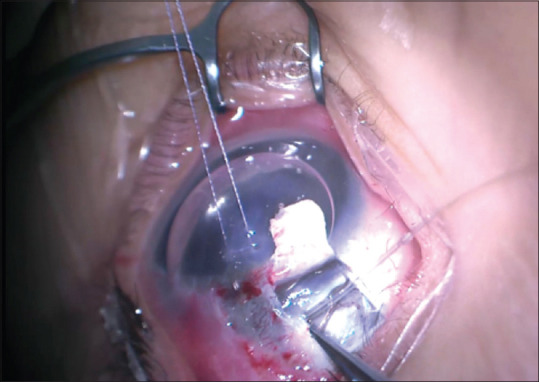

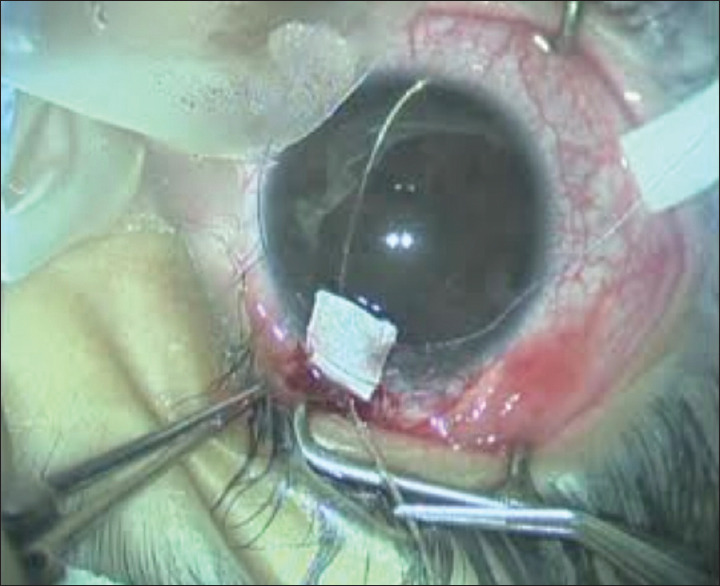

At this point, a microcatheter (iTRACK 250A; iScience Interventional, Menlo Park, CA, USA) was introduced into Schlemm's canal and threaded along the entire circumference of the canal [Figure 1]. Successful 360° catheterization was achieved when the catheter exited from the opposite end of Schlemm's canal [Figure 2]. The two ends of the microcatheter were then grasped and pulled in the opposite directions, which resulted in complete incision of Schlemm's canal [Figure 3]. During this process, the microcatheter was sometimes misdirected or encountered an obstruction. In such instances, the conjunctiva was dissected, and the sclera was cut over the illuminated tip of the catheter. This step was followed by grasping and pulling the two ends of the catheter, thereby resulting in partial incision of Schlemm's canal. Subsequently, the deep scleral flap was cut. Two nylon sutures (#10-0) were then used to loosely close the first sclera flap and a Vicryl suture (#9-0) was used to close the conjunctiva.

Figure 1.

Introduction of the tip of an illuminated microcatheter into Schlemm's canal and threading along the entire circumference of the canal

Figure 2.

Successful 360° catheterization, demonstrated by catheter exit from the opposite cut end of the canal

Figure 3.

The two ends of the illuminated microcatheter are grasped and pulled in the opposite directions, resulting in incision of Schlemm's canal

Postoperatively, patients were instructed to use 1% prednisolone acetate eye drops (Pred Forte; Allergan, Irvine, CA, USA) (six times per day for 6 weeks) and topical moxifloxacin 0.5% (four times per day for 2 weeks).

Data analysis

Data are summarized as mean ± standard deviation or median (range), as appropriate. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare within-patient data that were not normally distributed. Paired and unpaired t-tests were used for normally distributed data. The normality of the data was checked by using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Circumferential trabeculotomy was performed using an illuminated microcatheter in 16 eyes with PCG. The mean patient age was 75.1 ± 69.4 months (range, 4.0–216.0 months) at the time of surgery. Eight patients (50%) were male patients. Clinical and ocular characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. Complete catheterization was achieved in 11 patients. Partial catheterization was achieved in five patients. The mean follow-up duration was 20.3 ± 9.0 months (range, 12.0–36.0 months). In all 16 eyes (including both complete and incomplete catheterization), IOP was reduced from 31.8 ± 6.6 mmHg preoperatively to 15.6 ± 3.7 mmHg during the final follow-up visit (P < 0.001) [Table 2]. However, the difference in IOP reduction between complete and incomplete catheterization groups was not statistically significant (P = 0.271) [Table 3]. The mean preoperative number of glaucoma medications was 3.9 ± 0.5, which was reduced to 1.1 ± 1.6 at the final follow-up (P = 0.001).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with primary congenital glaucoma, before and after illuminated circumferential trabeculotomy surgery

| Patient/eye | Age at surgery (months) | Sex | Previous surgery | Trabeculotomy degrees | Preoperative |

Follow-up duration | Postoperative (at the last follow-up visit) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acuity | IOP | C/D | Number of medications | Acuity | IOP | C/D | Number of medications | ||||||

| 1/OD | 20 | Female | DS | 360 | F and F | 30 | 0.4 | 2 | 24 | F and F | 13 | 0.4 | 0 |

| 2/OD | 4 | Female | DS | 200 | F and F | 26 | 0.6 | 4 | 36 | F and F | 11 | 0.6 | 2 |

| 3/OS | 86 | Female | DS | 360 | 20/20 | 22 | 0.5 | 4 | 36 | 20/20 | 9 | 0.4 | 0 |

| 4/OD | 63 | Female | DS | 360 | 20/30 | 22 | 0.7 | 4 | 36 | 20/20 | 19 | 0.5 | 0 |

| 5/OD | 20 | Male | DS | 360 | F and F | 38 | 0.85 | 4 | 18 | F and F | 23 | 0.9 | 4 |

| 6/OD | 46 | Female | DS | 270 | F and F | 30 | 0.85 | 4 | 12 | F and F | 20 | 0.85 | 4 |

| 7/OD | 108 | Male | T and T | 180 | 20/100 | 29 | 0.9 | 4 | 18 | 20/50 | 20 | 0.9 | 3 |

| 8/OS | 17 | Female | T and T | 270 | F and F | 23 | 0.5 | 4 | 24 | F and F | 16 | 0.5 | 1 |

| 9/OS | 12 | female | DS | 360 | F and F | 33 | 0.5 | 4 | 18 | F and F | 13 | 0.5 | 0 |

| 10/OS | 189 | Male | T and T | 360 | 20/30 | 36 | 0.9 | 4 | 18 | 20/30 | 14 | 0.9 | 0 |

| 11/OD | 195 | Male | DS×2 | 360 | 20/400 | 41 | 0.9 | 4 | 12 | 20/400 | 13 | 0.9 | 0 |

| 12/OS | 96 | Male | DS | 360 | 20/40 | 38 | 0.3 | 4 | 24 | 20/30 | 12 | 0.3 | 0 |

| 13/OS | 20 | Male | DS | 360 | F and F | 30 | 0.8 | 4 | 12 | F and F | 16 | 0.8 | 0 |

| 14/OS | 50 | Female | DS | 360 | F and F | 30 | 0.4 | 4 | 12 | 20/60 | 16 | 0.4 | 0 |

| 15/OD | 216 | Male | DS | 300 | 20/400 | 42 | 0.9 | 4 | 12 | 20/400 | 17 | 0.9 | 3 |

| 16/OS | 60 | Male | DS | 360 | F and F | 38 | 0.4 | 4 | 12 | F and F | 17 | 0.4 | 0 |

OD: Right eye, OS: Left eye, DS: Deep sclerectomy, T and T: Combined trabeculotomy and trabeculectomy, F and F: Fix and follow, IOP: Intraocular pressure, C/D: Cup-to-disc ratio

Table 2.

Comparison of preoperative and postoperative parameters

| Parameter | Preoperative | Postoperative | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOP (mmHg) | Mean±SD | 31.8±6.6 | 15.6±3.7 | <0.001† |

| Median (range) | 30.0 (22.0-42.0) | 16.0 (9.0-23.0) | <0.001‡ | |

| C/D ratio | Mean±SD | 0.6±0.2 | 0.6±0.2 | 0.285† |

| Median (range) | 0.6 (0.3-0.9) | 0.6 (0.3-0.9) | ||

| Medications | Mean±SD | 3.9±0.5 | 1.1±1.6 | 0.001† |

| Median (range) | 4.0 (2.0-4.0) | 0 (0-4.0) |

†Wilcoxon signed-rank test; ‡Paired t-test. IOP: Intraocular pressure, C/D: Cup-to-disc ratio, SD: Standard deviation

Table 3.

Comparison of intraocular pressure changes between extent of circumferential trabeculotomy

| Trabeculotomy extent | Preoperative IOP | Postoperative IOP | Change in IOP | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 360° (n=11) | 32.5±6.4† | 15.0±3.8 | 17.5±6.9 | <0.001‡ |

| <360° (n=5) | 30.0±7.2 | 16.8±3.7 | 13.2±7.2 | <0.015‡ |

| Difference | - | - | 4.3 | 0.271§ |

†All values are shown as mean±SD, ‡Paired t-test, §Unpaired t-test. SD: Standard deviation, IOP: Intraocular pressure

During the follow-up period, 15 of the 16 patients demonstrated stable optic nerve cupping and all corneas remained clear. The remaining patient [patient number 5 in Table 1] required additional glaucoma surgery because the IOP remained above the target level despite maximal medical therapy. The sole complications encountered during or after surgery comprised early postoperative hyphema in six eyes (37.5%). These complications resolved during the 1st week postoperatively in all patients.

Discussion

Although goniotomy and trabeculotomy ab externo are the primary surgical treatment for PCG,[10] they have a low success rate in the Middle East, where patients often exhibit severe PCG.[5,11,12] Combined trabeculectomy trabeculotomy and tube drainage surgery have also been described as alternative treatment options; both are associated with vision-threatening complications.[4,13] An important advancement in trabeculotomy techniques has involved the capability to navigate Schlemm's canal, initially using a 6-0 polypropylene suture described by Beck and Lynch.[7] However, this technique has been associated with suture misdirection and false passage.[8] Subsequent method describe a 360° incision of the Schlemm's canal by means of a conjunctiva-sparing, ab interno approach (i.e., gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy).[14] Nonetheless, this technique also requires a clear cornea. An additional advancement includes circumferential trabeculotomy by mean of MAT for cannulation and incision of Schlemm's canal.[9] This approach has the main benefit of an atraumatic flashing tip, which facilitates appropriate insertion and prevents risks associated with misdirection.

In this retrospective study of 16 eyes with PCG that underwent MAT as a secondary procedure following unsuccessful primary surgery, 94% of the eyes exhibited good outcomes. These outcomes included controlled IOP, stabilization of ocular parameters, and prevention of vision-threatening complications. El Sayed and Gawdat.[15] reported lower IOP and the need for fewer glaucoma medications following this procedure, in comparison with conventional rigid probe trabeculotomy. Moreover, Shi et al.[16] revealed that IOP and medication use were both significantly reduced in patients with PCG who underwent MAT after unsuccessful angle surgeries. These findings are consistent with the results of our study, in which most patients showed significant IOP reduction and reduction of the number of glaucoma medications postoperatively [Table 2].

In our case series of 16 eyes, we achieved a success rate of 93.75%. This rate is similar to the success rates in previous studies that used a similar surgical approach. In a case series of 16 eyes, Sarkisian[9] demonstrated a complete success rate of 75%. In another case series of 24 eyes, Girkin et al.[17] achieved a complete success rate of 83.3%. The variations among studies may be attributable to differences in sample size and divergent definitions of “success.” In the study by Sarkisian,[9] the success rate was defined by the extent of trabeculotomy. In contrast, Girkin et al.[17] defined complete success as IOP <21 mm Hg, without the use of antiglaucoma medications. Similarly, our study defined success as IOP ≤21 mmHg, with or without the use of glaucoma medications.

MAT has been found to achieve lesser canalization of Schlemm's canal in previously operated eyes, compared with eyes that are undergoing the initial operation. This is presumably because of damage to Schlemm's canal during previous angle surgeries.[16] In our study, complete catheterization was achieved in one eye that had previously undergone angle surgery. Complete catheterization was also achieved in 10 eyes that had undergone non-penetrating deep sclerectomy [Table 1]. However, both IOP reduction and safety were similar for eyes in which full catheterization was achieved and those in which partial catheterization was achieved [Table 3]. These results are consistent with previous findings concerning a non-statistically significant difference in mean IOP reduction between eyes that underwent 360° trabeculotomy and those that underwent partial trabeculotomy using MAT.[16]

This study revealed that no associated vision-threatening complications arose as a consequence of MAT. However, 37.5% of study participants (6 of 16) showed self-limiting transient hyphema during the early postoperative period. Previous studies using this technique have also found transient hyphema in 43.6%–100% of the studied eyes.[9,17,18,19]

This study had some limitations, including its small sample size and retrospective nature. Thus, there remains a need for more prospective randomized controlled studies with more patients and longer follow-up intervals to confirm our findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings suggest that MAT is an effective and safe strategy for use as a secondary procedure in patients with PCG who have undergone unsuccessful glaucoma surgery.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Marchini G, Toscani M, Chemello F. Pediatric glaucoma: Current perspectives. Pediatric Health Med Ther. 2014;5:15–27. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Obeidan SA, Osman Eel-D, Dewedar AS, Kestelyn P, Mousa A. Efficacy and safety of deep sclerectomy in childhood glaucoma in Saudi Arabia. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014;92:65–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2012.02558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson DR. The development of the trabecular meshwork and its abnormality in primary infantile glaucoma. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1981;79:458–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu Chan JY, Choy BN, Ng AL, Shum JW. Review on the management of primary congenital glaucoma. J Curr Glaucoma Pract. 2015;9:92–9. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10008-1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson DR. Trabeculotomy compared to goniotomy for glaucoma in children. Ophthalmology. 1983;90:805–6. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(83)34484-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russell-Eggitt IM, Rice NS, Jay B, Wyse RK. Relapse following goniotomy for congenital glaucoma due to trabecular dysgenesis. Eye (Lond) 1992;6(Pt 2):197–200. doi: 10.1038/eye.1992.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beck AD, Lynch MG. 360 degrees trabeculotomy for primary congenital glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:1200–2. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100090126034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neely DE. False passage: A complication of 360 degrees suture trabeculotomy. J AAPOS. 2005;9:396–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarkisian SR., Jr An illuminated microcatheter for 360-degree trabeculotomy [corrected] in congenital glaucoma: A retrospective case series. J AAPOS. 2010;14:412–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ozawa H, Yamane M, Inoue E, Yoshida-Uemura T, Katagiri S, Yokoi T, et al. Long-term surgical outcome of conventional trabeculotomy for childhood glaucoma. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2017;61:237–44. doi: 10.1007/s10384-017-0506-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McPherson SD, Jr, Berry DP. Goniotomy vs external trabeculotomy for developmental glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1983;95:427–31. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(83)90260-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Debnath SC, Teichmann KD, Salamah K. Trabeculectomy versus trabeculotomy in congenital glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1989;73:608–11. doi: 10.1136/bjo.73.8.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagdy FM. Ab externo 240-degree trabeculotomy versus trabeculotomy-trabeculectomy in primary congenital glaucoma. Int Ophthalmol. 2020;40:2699–2706. doi: 10.1007/s10792-020-01453-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grover DS, Smith O, Fellman RL, Godfrey DG, Butler MR, Montes de Oca I, et al. Gonioscopy assisted transluminal trabeculotomy: An ab interno circumferential trabeculotomy for the treatment of primary congenital glaucoma and juvenile open angle glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99:1092–6. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-306269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El Sayed Y, Gawdat G. Two-year results of microcatheter-assisted trabeculotomy in paediatric glaucoma: A randomized controlled study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2017;95:e713–9. doi: 10.1111/aos.13414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi Y, Wang H, Yin J, Zhang X, Li M, Xin C, et al. Outcomes of microcatheter-assisted trabeculotomy following failed angle surgeries in primary congenital glaucoma. Eye (Lond) 2017;31:132–9. doi: 10.1038/eye.2016.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Girkin CA, Rhodes L, McGwin G, Marchase N, Cogen MS. Goniotomy versus circumferential trabeculotomy with an illuminated microcatheter in congenital glaucoma. J AAPOS. 2012;16:424–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Temkar S, Gupta S, Sihota R, Sharma R, Angmo D, Pujari A, et al. Illuminated microcatheter circumferential trabeculotomy versus combined trabeculotomy-trabeculectomy for primary congenital glaucoma: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159:490–7.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Girkin CA, Marchase N, Cogen MS. Circumferential trabeculotomy with an illuminated microcatheter in congenital glaucomas. J Glaucoma. 2012;21:160–3. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31822af350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]