Abstract

Objectives

Cynical hostility is a cognitive schema according to which people cannot be trusted, and it has associations with individuals’ loneliness. The present study takes a dyadic approach to examine whether cynical hostility is related to one’s own and their spouse’s loneliness. We further explore whether friendship factors serve as a mediator between individuals’ and spouses’ cynical hostility and loneliness.

Method

We used 2 waves of the Health and Retirement Study (N = 1,065 couples) and Actor-Partner Interdependence Models (APIMs) with mediation to examine the proposed model. Mediation was tested with the construction of path models and significance levels were reached using bootstrapping.

Results

For both husbands and wives, cynical hostility was significantly associated with loneliness. Husband’s loneliness was also significantly associated with his wife’s cynical hostility, but wife’s loneliness was not associated with her husband’s cynical hostility. We further found that the association between wife’s own cynical hostility and loneliness was mediated by lower levels of contact with, and support from friends. Friendship factors did not serve as mediators for husbands.

Discussion

Husbands and wives who have higher levels of cynical hostility may be more vulnerable to loneliness. High levels of cynical hostility in women may be related to deficits in their quantity and quality of friendship, and thus be associated with loneliness. Men who are married to women with a higher level of cynical hostility may experience increased loneliness, but this relationship is not explained by men’s friendships.

Keywords: Cynical hostility, Dyads, Friendship, Loneliness, Marital relationships

Cynical hostility and loneliness are both social-cognitive schemas. Cynical hostility is characterized by the belief that people are not to be trusted and are a source of wrongdoing (Smith, 1994). Loneliness is defined as a perceived gap between desired and obtained social relationships (Peplau & Perlman, 1982). Both loneliness and cynical hostility have been examined separately as predictors of health in later life, with findings indicating that both are associated with declines in individuals’ physical and mental health (Graham et al., 2006; Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2004; Valtorta et al., 2016). The relationship between cynical hostility and loneliness has not been thoroughly examined, with the exception of a recent paper suggesting theoretical and statistical links between individuals’ cynical hostility and loneliness (Segel-Karpas & Ayalon, 2019).

Despite known links between couples’ loneliness (Stokes, 2016), the relationship between cynical hostility and spouse’s loneliness has not been previously examined. Spouse’s loneliness is of interest as it places loneliness in the social context of a marital relationship. Although the marital relationship is associated with numerous benefits for individuals’ well-being, including reduced loneliness (Ayalon et al., 2013), studies have also shown that poor quality marital relationships have associations with greater loneliness (Ayalon et al., 2013; Hsieh & Hawkley, 2018). Furthermore, individuals age within a marital relationship. Retirement or an empty nest could result in an enhanced focus on the marital relationship, highlighting the reciprocal effects of partners on one another in older adulthood (Hoppmann & Gerstorf, 2009). For these reasons, it is necessary to study the associations between partner’s cognitions and dispositions, including cynical hostility, and individuals’ loneliness among older adult couples. Therefore, the first goal of this research is to test whether spouse’s cynical hostility is linked to individual’s loneliness.

While the marital relationship can be an invaluable source for social interaction, friendship also plays a major role in one’s social life. Friendship support, friendship strain, marital support, and marital strain have all been found to mediate the relationship between loneliness and well-being (Chen & Feeley, 2014). The expression of cynical hostility may not only be associated with individuals’ own social relationships, making them less desirable social partners, but also their spouses’ social relationships. For example, a spouse’s friends may choose not to go to dinner with the couple or avoid visiting the couple’s home if it means the friends have to be around the individual’ spouse that has a higher level of cynical hostility. The second goal of this paper is to examine whether the relationships between individual’s cynical hostility, spouse’s cynical hostility, and individual’s loneliness are mediated via individual’s friendships. Thus, we use a dyadic framework and examine whether individuals’ cynical hostility is related to their own and their spouses’ loneliness, and whether this association operates through one’s relationships with friends, focusing on contact with friends, friendship strain, and friendship support.

Loneliness and Cynical Hostility

Recently, Segel-Karpas and Ayalon (2019) suggested that loneliness and cynical hostility have meaningful theoretical and empirical links. Both loneliness and cynical hostility are cognitive schemas of the self in relation to others. Lonely people perceive others as not being close enough to fulfill their social needs, whereas people with a higher level of cynical hostility perceive others as untrustworthy, a potential threat, and a source of wrongdoing (Peplau & Perlman, 1982; Smith et al., 2004). Therefore, both loneliness and cynical hostility are schemas characterized by a sense of aloneness and vulnerability (Curtis & Jones, 2020; Segel-Karpas & Ayalon, 2019).

Although the suggested relationships between loneliness and cynical hostility can be bidirectional (Segel-Karpas & Ayalon, 2019), in this paper, we focus on the role of cynical hostility as the predictor of loneliness. First, the basic mistrust characterizing those with a higher level of cynical hostility can result in increased stress in social interactions, potentially leading to decreased enjoyment, as well as lower levels of perceived support (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2008) and the inability to gain support when needed (Chen et al., 2005; Lepore, 1995). Both high stress and low social support may make the individuals with a higher level of cynical hostility more vulnerable to poor social relationships, possibly increasing their loneliness. Additionally, the perception of others as a source of wrongdoing, which characterizes those with a higher level of cynical hostility, may deter individuals from seeking out social relationships, which may also be linked to loneliness (Segel-Karpas & Ayalon, 2019). Finally, hostility is also expressed in behavior (Barefoot et al., 1993), and could make individuals with a higher level of cynical hostility unattractive social counterparts, potentially leading to greater loneliness as others may not wish to interact with them (Segel-Karpas & Ayalon, 2019).

Cynical Hostility and Loneliness in Couples

The potential relationship between cynical hostility and loneliness is not limited to individual’s own social relationships, but also to one’s spouse. A prior cross-sectional study has shown that having a spouse with a higher level of cynical hostility is related to greater depressive symptoms for women, but not for men (Brummett et al., 2000). We argue that being married to a spouse with a higher level of cynical hostility may also be related to loneliness via couples’ social engagements. As both members of the couple often engage in joint activities and social interactions (Kalmijn & Bernasco, 2001), it is possible that a spouse with a higher level of cynical hostility will behave in a manner that deems the couple as less attractive social counterparts, which may lead to increased loneliness. It is also possible that individuals with a higher level of cynical hostility are less interested in social interactions and may discourage their spouses from socially engaging with others. This, in turn, may be associated with decreased social contact and increased loneliness. In this study, we suggest that individual’s loneliness is linked to their own and spouse’s cynical hostility via individual’s relationships with friends.

Friendship as a Potential Mediator

Friendship is characterized by fewer norms and requires additional effort to maintain compared to family and spousal relationships. As such, friendship offers a relationship characterized by greater flexibility in interactions compared to more obligatory relationships, such as those with a spouse or family members (Bolger & Eckenrode, 1991). Additionally, interacting with friends is associated with greater levels of life satisfaction compared to interactions with family members (Huxhold et al., 2014). However, friendships may be more susceptible to external strains due to its less obligatory nature.

Individuals’ friendship contact, support, and strain will be examined as potential mediators between cynical hostility and loneliness as they constitute two dimensions of friendship. Support and strain represent friendship quality, whereas contact with friends represent a quantitative, structural measure of friendship. Quantitative relationship measures (i.e., friendship contact) tend to have fewer associations with loneliness than qualitative relationship measures (i.e., friendship support and strain), meriting the inclusion of these two dimensions of friendship (Pinquart & Sorensen, 2001).

There are several reasons why friendship support, strain, and contact could serve as potential mediators between own cynical hostility and own and spouse’s loneliness in the present study. First, friends serve as a source of support and friendship factors have associations with loneliness. For example, among older adults, greater friendship strain is related to greater loneliness levels over time (Hawkley & Kocherginsky, 2018). Using growth mixture modeling, Ermer et al. (2020) found that wives’ lower levels of contact with friends was associated with being in a class characterized by high levels of loneliness; this pattern was not found for husbands. Additionally, friendship has stronger associations with loneliness as compared to family relationships (Pinquart & Sorensen, 2001), warranting the inclusion of friendship, rather than other social relationships such as family, in the present study.

Cynical hostility and friendship may also have meaningful associations. Holt-Lunstad et al. (2008) found that there were negative associations between cynical hostility and social support. They suggested that those that have a higher level of cynical hostility are more likely to perceive their friends as less friendly, and, as a result, less supportive. Both own and spouse’s cynical hostility may be linked to decreased contact with friends because, as previously stated, the expression of cynical hostility may make the individual with a higher level of cynical hostility and his or her spouse less attractive counterparts. Additionally, a spouse with a higher level of cynical hostility may also discourage couple-orientated gatherings, therefore, decreasing partner’s opportunities for social contact and support, and increasing his or her loneliness. The expression of cynical hostility could also be associated with greater strain and decreased support in the relationship with friends, as the expression of cynical hostility is usually considered unacceptable and may cause conflicts as well as reduce friends’ willingness to offer support.

We also propose that there might be gender differences for how friendship may or may not mediate the relationship between cynical hostility and loneliness. For women, greater friendship support is linked to their own higher levels of emotional well-being, whereas this significant association is not found for husbands (Ermer & Proulx, 2020), signaling how husbands and wives may have differing experiences within their friendships. Conversely, compared to wives, husbands tend to have couple-oriented friendships (Davidson, 2004) and are more reliant on their spouse for social support (Okun & Keith, 1998). This could suggest that there should be a stronger association between spouses’ cynical hostility and loneliness for husbands, compared to wives. Following this same line of thought, women’s own hostility may be a stronger predictor of their own friendship experiences, compared to men, which may serve as a mediator between her own cynical hostility and loneliness.

Current Study

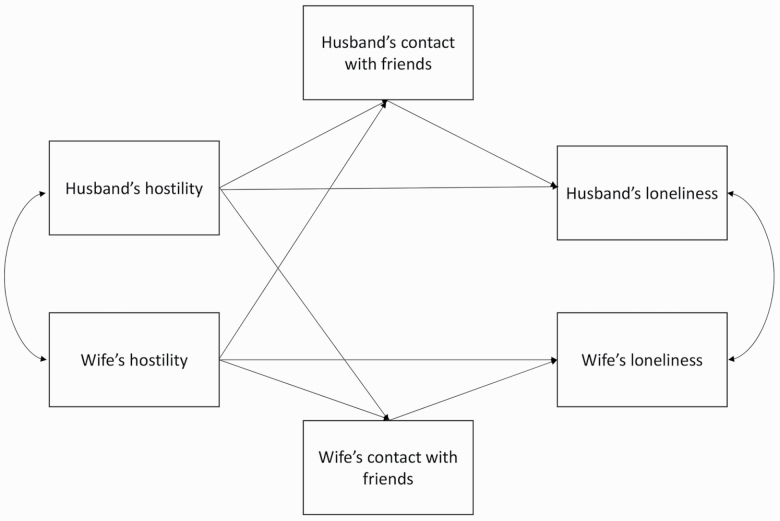

The current study takes a dyadic approach to the study of cynical hostility and loneliness. Most previous studies concentrated on the adverse effects that cynical hostility has on physical health (e.g., Smith et al., 2004), generally overlooking its possible social consequences. Similarly, loneliness is often examined in the context of individuals’ own social relationships, neglecting to examine the effects individuals’ attitudes and behaviors may have on their spouses’ loneliness. We argue that an individual’s friendship quality and quantity of contact may be associated with their own and their spouse’s cynical hostility and, through this process, be linked to loneliness for both marital partners (see Figure 1). Based on the reviewed literature, our hypotheses are as follows:

Figure 1.

Theoretical model of the relationship between couples’ hostility and loneliness as mediated by husbands’ and wives’ contact with friends.

Cynical hostility will be positively related to loneliness:

H1a: Husbands’ and wives’ cynical hostility will be positively associated with their own loneliness

H1b: Husbands’ cynical hostility will be positively associated with wives’ loneliness.

H1c: Wives’ cynical hostility will be positively associated with husbands’ loneliness.

Cynical hostility will be related to loneliness via indirect effects on:

H2: The frequency of contact with friends, such that greater hostility (both one’s own and a spouse’s) will be related to one’s own decreased social contact with friends. This, in turn, will be associated with increased loneliness

H3: Friendship support, such that greater hostility (both one’s own and a spouse’s) will be related to one’s own decreased social support from friends. Decreased social support from friends, in turn, will be associated with increased loneliness.

H4: Friendship strain, such that greater hostility (both one’s own and a spouse’s) will be related to one’s own increased strain with friends. Increased strain with friends, in turn, will be associated with increased loneliness.

Method

Participants

Data were derived from two waves of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) collected in 2006 and 2010. The HRS is a nationally representative study of the population in the United States of adults aged 50 and older, and their spouses regardless of age. The HRS is an open dataset (pre-registration is required), and can be easily accessed via the website. The first wave of data of the HRS was collected in 1992, and in 2-year intervals thereafter. Starting 2006, the HRS team assigned half the sample to participate in a lifestyle and psychosocial questionnaire (the “leave behind”). The other half of the sample was administered the leave behind in the following wave, such that longitudinal data are available in 4-year intervals. Response rates for the leave behind questionnaire were 87.7% in 2006 and 73.1% in 2010 out of the eligible respondents.

The current study includes 1065 married couples. Inclusion criteria required that participants be continuously married to one another at both 2006 and 2010 and completed the lifestyle and psychosocial questionnaire.

Measurements

Loneliness

Loneliness was measured using a shortened three-item version of the Revised UCLA Loneliness scale (Hughes et al., 2004). Respondents were asked to rate the frequency in which they feel a lack of companionship, left out, and isolated, on a scale ranging from hardly ever or never (1) to often (3). Final scores were computed as the mean of the three items (α = .81 and α = .80 for men and women respectively, in both 2006 and 2010). Data were missing for 13% of men and 14% of women.

Cynical hostility

Cynical hostility was measured using five items from the Cook-Medley Hostility Inventory (Cook & Medley, 1954; Costa Jr et al., 1986). Respondents were asked to rate their agreement with the five statements (“most people dislike putting themselves out to help other people”; “most people will use somewhat unfair means to gain profit or an advantage rather than lose it”; “no one cares much what happens to you”; “I think most people would lie in order to get ahead”; and “I commonly wonder what hidden reasons another person may have for doing something nice for me”). These items were assessed on a scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (6). Final score was computed as the average across items (α = .81 and α = .79 for men and women in 2006; α = .80 and α = .79 for men and women in 2010). Data were missing for 13% of men and women.

Contact with friends

Contact with friends was measured using three items, assessing the frequency of contact with friends via meetings, phone calls, and writing. Scale ranged from less than once a year or never (1) to three or more times a week (6). A final score was created by summing the items.

Friendship support

Friendship support was measured using three items rated on a scale ranging from not at all (1) to a lot (4). Respondents were asked how much “their friends understand the way they feel about things,” “they can rely on their friends if they have a serious problem,” and “they can open up to their friends if they need to talk about their worries.” A summary score was created by averaging the items (α = .81 and α = .84 for men and women in 2006; α = .82 and α = .85 for men and women in 2010).

Friendship strain

Friendship strain was measured using four items rated on a similar scale to support. Respondents were asked how much their friends “make too many demands,” “criticize them,” “let them down,” and “get on their nerves” (α = .76 and α = .74 for men and women in 2006; α = .75 and α = .74 for men and women in 2010).

Covariates

The covariates were all measured in 2006 and included age, race (0 = non-White, 1 = White), activities of daily living (ADL), and household income (measured using a hyperbolic inverse sine transformation to account for non-normality). These covariates were chosen due to their known relationship with loneliness (Drageset, 2004; Victor & Yang, 2012; Wu & Penning, 2015). The ADL measure consists of five activities (i.e., bathing, eating, dressing, walking across a room, and getting in or out of bed). These activities were rated as the participant having no difficulty (0) or difficulty (1) on each task. Scores were summed and ranged from 0 to 5. We also controlled for support and strain in the marital relationship, as we were interested in examining the relationship between spouse’s cynical hostility and one’s social relationships and loneliness above and beyond its associations with marital quality. Support and strain in the relationship with one’s spouse were measured with the same items as support and strain with friends, but with the focus on the marriage (perceived support: α = .72 and α = .81 for men and women, respectively; perceived strain: α = .75 and α = .78 for men and women, respectively).

Analytical Strategy

We used an Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) to examine our first hypotheses concerning the dyadic effects of loneliness on cynical hostility. Using an APIM, individuals’ loneliness was regressed on their own and their spouses’ cynical hostility, while controlling for individuals’ baseline loneliness and individuals’ baseline covariates. Throughout this paper, actor effects will refer to the link between individuals’ own hostility and their own loneliness. Partner effects will refer to the link between individuals’ own hostility and their spouses’ loneliness.

To test hypotheses H2–H4, we conducted a path model in Mplus using an APIM framework. To start, we assessed the same path model as in the first step, with direct effects between actor’s and partner’s cynical hostility at T1 and actor’s loneliness at T2, and included indirect effects through the friendship frequency of contact, support, and strain all at T2, as reported by the actor. We controlled for individuals’ own baseline loneliness and the covariates. Furthermore, each mediator at T2 was regressed on its T1 measurement and on partner’s cynical hostility, in addition to the covariates. To assess if the indirect effects of cynical hostility on loneliness through the friendship variables were significant, we conducted bootstrapping with 95% confidence intervals (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). All estimates are reported using STDYX standardization, except for Wald tests, which used unstandardized estimates.

We also assessed whether certain paths significantly differed. Chi-squared difference tests were used to test whether husbands’ and wives’ actor and partner effects differed between and within groups: for example, whether husbands’ actor and partner effects significantly differed (i.e., within gender) and whether husbands’ and wives’ actor effects significantly differed (i.e., between gender). Wald testing was used to assess the differences between husbands’ and wives’ indirect effects (Muthén & Muthén, 2017), testing how mediation operated on actor and partner effects within gender (e.g., differences between actor and partner effects for wives) and between gender (e.g., differences between actor effects for husbands and wives). Significant differences are reported in text. See Supplementary Appendix 1 for full results.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations between study variables are presented in Table 1 for within individual correlations, and in Table 2 for dyadic correlations. Husband’s and wife’s loneliness were significantly correlated at T1 (r = .29, p < .001) and T2 (r = .28, p < .001). Husband’s loneliness at T2 was significantly correlated with wife’s T1 cynical hostility (r = .16, p < .001), and wife’s loneliness was significantly correlated with husband’s cynical hostility (r = .16, p < .001).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Between Own Covariates and Study’s Variables

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 64.81 | 8.39 | .01 | .14*** | −.12*** | .05* | −.05 | .10*** | −.08** | −.13*** | −.06* | −.11*** | −.06* | −.06* | −.14*** | −.14*** | 61.49 | 8.63 | |

| 2. ADL | 0.11 | 0.46 | .01 | −.07*** | −.18*** | −.09*** | .08** | .11*** | −.06* | .07** | −.07** | .13*** | .13*** | −.06* | −.001 | −.05* | 0.14 | 0.55 | |

| 3. Racea | 0.85 | 0.35 | .12*** | −.07*** | .14*** | .08** | −.09*** | −.07* | .02 | −.12*** | .10*** | −.18*** | −.03 | −.01 | −.07* | .08** | 0.86 | 0.35 | |

| 4. Income | 11.67 | 1.13 | −.15*** | −.10*** | .13*** | .08** | −.07** | −.05 | .06* | .004 | .18*** | −.18*** | −.06* | .09** | .02 | .20*** | 11.67 | 1.13 | |

| 4. Support spouse | 3.64 | 0.49 | .06* | −.07** | .11*** | .06* | −.58*** | −.44** | .15*** | −.10** | .10*** | −.20*** | −.3*** | .16*** | −.06* | .113 | 3.47 | 0.60 | |

| 5. Strain spouse | 1.91 | 0.60 | −.06* | .06* | −.07** | −.02 | −.47*** | .44*** | −.10*** | .25*** | −.10*** | .21*** | .30*** | −.14*** | .14*** | −.09** | 1.99 | 0.65 | |

| 6. Loneliness T1 | 1.36 | 0.47 | −.13*** | .09** | −.04 | −.04 | −.43*** | .38*** | −.19*** | .23*** | −.21*** | .31*** | .59*** | −.17*** | .20*** | −.164 | 1.39 | 0.48 | |

| 8. Support friends T1 | 2.8 | 0.70 | .02 | −.03 | −.004 | .03 | .14*** | −.06* | −.18*** | −.09** | .38*** | −.23*** | −.15*** | .54*** | −.07* | .30*** | 3.19 | 0.71 | |

| 9. Strain friends T1 | 1.43 | 0.48 | −.11*** | .05 | −.05 | −.08** | −.12*** | .25*** | .25*** | −.03 | .068 | .24*** | .15*** | −.07** | .45*** | .03 | 1.42 | 0.47 | |

| 10. Contact friends T1 | 10.53 | 3.06 | −.07** | −.03 | .07** | .20*** | .05 | −.06* | −.13*** | .31*** | .04 | −.20*** | −.14*** | .28*** | .02 | .58*** | 11.57 | 3.05 | |

| 11. Hostility T1 | 3.13 | 1.11 | −.08** | .10*** | −.15*** | −.18*** | −.22*** | .19*** | .29*** | −.21*** | .29*** | .18*** | .27*** | −.21*** | .16*** | −.20*** | 2.72 | 1.07 | |

| 12. Loneliness T2 | 1.33 | 0.47 | −.08** | .12*** | −.02 | −.06* | −.34*** | .29*** | .58*** | −.12*** | .18*** | −.13*** | .24*** | −.18*** | .21*** | −.19*** | 1.37 | 0.47 | |

| 13. Support friends T2 | 2.83 | 0.73 | .004 | .001 | −.04 | .05 | .11*** | −.06 | −.12*** | .50*** | −.03 | .23*** | −.13*** | −.15*** | −.11*** | .38*** | 3.17 | 0.72 | |

| 14. Strain friends T2 | 1.38 | 0.45 | −.15*** | .03 | −.10*** | −.07* | −.10*** | .18*** | .15*** | −.01 | .47*** | .04 | .20*** | .19*** | −.008 | .04 | 1.37 | 0.44 | |

| 15. Contact friends T2 | 10.78 | 3.14 | −.12*** | −.09** | .08** | .19*** | .06* | −.07* | −.12*** | .18*** | .004 | .56*** | −.19*** | −.19*** | .30*** | .06* | 11.93 | 3.12 |

Notes: ADL = activities of daily living. The left-hand side displays estimates for men, and the right-hand side displays estimates for women.

a1 = White, 0 = non-White. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Table 2.

Dyadic Correlations of Study’s Variables

| Women | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 1. Loneliness T1 | .29*** | .14*** | −.06* | .12*** | −.07** | −.06* | .08** | −.04 | .21*** |

| 2. Hostility T1 | .18*** | .33*** | −.11*** | .11*** | −.15*** | −.09** | .09** | −.14*** | .16*** |

| 3. Support T1 | −.10** | −.13** | .22*** | −.05 | .14*** | .19*** | −.04 | .14*** | −.10** |

| 4. Strain T1 | .10** | .10** | .002 | .19*** | −.05 | −.01 | .11*** | −.02 | .06* |

| 5. Contact T1 | −.11*** | −.18*** | .13*** | .03 | .31*** | .12*** | .03 | .24*** | −.12*** |

| 6. Support T2 | −.12*** | −.08** | .12*** | .02 | .13*** | .20*** | −.05 | .12*** | −.11*** |

| 7. Strain T2 | .06* | .15*** | −.02 | .25*** | −.06* | −.02 | .17*** | .001 | .02 |

| 8. Contact T2 | −.11*** | −.16*** | .12*** | .01 | .25*** | .10** | .02 | .29*** | −.16*** |

| 9. Loneliness T2 | .24*** | .16*** | −.10*** | .05 | −.13*** | −.07* | .03 | −.10** | .28*** |

Note: *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

To test the first hypotheses suggesting the husband’s and wife’s cynical hostility levels will result in their spouse’s and their own increased loneliness, we used an APIM, regressing both partners’ loneliness levels at T2 on their own and partner’s levels of cynical hostility at T1, while controlling for their initial levels of loneliness and the covariates. Results indicated that a husband’s own cynical hostility (β = 0.059, p = .029) and his wife’s cynical hostility (β = 0.061, p = .029; see Table 3) were significantly associated with his own loneliness. However, a wife’s own cynical hostility (β = 0.091, p = .001), but not her husband’s cynical hostility (β = 0.010, p = .697), was associated with her own loneliness. Wives’ paths between their own hostility and loneliness (i.e., actor effect), and husbands’ hostility and wives’ loneliness significantly differed (i.e., partner effect; χ 2(1) = 4.048, p = .044). No other path differences were found (see Supplementary Table A).

Table 3.

Standardized Actor-Partner Effects of Hostility on Loneliness

| Husband’s loneliness T2 | Wife’s loneliness T2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

| Age | −0.024 | 0.025 | −0.011 | 0.023 |

| ADL | 0.046 | 0.037 | 0.044 | 0.032 |

| Racea | 0.064* | 0.026 | 0.042 | 0.026 |

| Income | −0.014 | 0.025 | −0.004 | 0.02 |

| Spouse support | −0.069* | 0.034 | −0.071 | 0.037 |

| Spouse strain | 0.041 | 0.029 | 0.009 | 0.033 |

| Loneliness T1 | 0.490** | 0.030 | 0.512** | 0.033 |

| Husband’s cynical hostility T1 | 0.059* | 0.027 | 0.010 | 0.026 |

| Wife’s cynical hostility T1 | 0.061* | 0.028 | 0.091** | 0.028 |

Notes: ADL = activities of daily living.

a1 = White, 0 = non-White.

*p < .05. **p < .01.

Next, we assessed whether contact with friend, friendship support, and friendship strain served as mediators between hostility and loneliness. One model was conducted for each friendship variable measured in T2, and controlled for at T1. Wives’ contact with friends significantly mediated the association between wives’ hostility and wives’ loneliness (β = 0.016, SE = 0.005, p = .003, CI: 0.008–0.057), and husbands’ contact with friends marginally mediated the link between wives’ hostility and husbands’ loneliness (β = 0.008, SE = 0.004, p = .052, CI: 0.001–0.007). Husbands’ friendship contact did not mediate the association between husbands’ hostility and husbands’ loneliness (β = 0.007, SE = 0.004, p = .109, CI: 0.000–0.007). Wives’ contact did not mediate the relationship between husbands’ hostility and wives’ loneliness (β = 0.005, SE = 0.004, p = .265, CI: −0.030 to 0.013). There was a marginally significant difference between wives’ own cynical hostility and loneliness, and husbands’ cynical hostility and wives’ loneliness (b = 0.005, SE = 0.003, p = .082). Other differences were not significant (see Supplementary Table B).

One significant indirect effect was found when assessing friendship support. The association between wives’ cynical hostility and wives’ loneliness operated through friendship support (b = 0.075, SE = 0.030, p = .011). Friendship support did not mediate the link between wives’ hostility and husbands’ loneliness (b = 0.001, SE = 0.002, p = .620), husbands’ hostility and husbands’ loneliness (b = 0.001, SE = 0.003, p = .760), or husbands’ hostility and wives’ loneliness (b = 0.000, SE = 0.004, p = .988). Wald tests found a marginal gender difference on friendship support serving as a mediator between husbands’ hostility and husbands’ loneliness, and wives’ hostility and wives’ loneliness (i.e., actor effects; [b = −0.004, SE = 0.002, p = .094]). No other significant differences were found (Supplementary Table C).

Friendship strain did not mediate any of the paths: husbands’ hostility to husbands’ loneliness: b = 0.003, SE = 0.002, p = .115; wives’ hostility to husbands’ loneliness: b = 0.001, SE = 0.001, p = .511; wives’ hostility to wives’ loneliness: b = 0.003, SE = 0.002, p = .103; and husbands’ hostility to wives’ loneliness: b = 0.000, SE = 0.002, p = .103. Due to mediation not occurring, we did not conduct formal path-differences testing.

Since marital strain and support were included as covariates in the model, we also tested the possibility that they might mediate the relationship between hostility and loneliness. We ran the models as described above using marital strain and support as mediators. We found only one significant mediator: marital strain mediated the relationship between husband’s own hostility and loneliness (b = 0.02, SE = 0.008, p = .045). The difference between the actor’s paths for husbands and wives was not significant (b = 0.001, p = .82).

Discussion

Theory and empirical findings connect cynical hostility and loneliness at the individual level (Segel-Karpas & Ayalon, 2019). Here, we suggest that it is not only an individual’s own cynical hostility that may be associated with loneliness, but also spouse’s cynical hostility. Using a dyadic framework and a longitudinal dataset, we found associations at both the actor and partner level between cynical hostility and loneliness, and found that these associations sometimes operated through friendship contact and support. Our results did differ somewhat for men and women in how spouses’ hostility was associated with loneliness.

Overall Findings in APIMs

Our main findings suggest that a wife’s cynical hostility is significantly associated not only with own, but also her husband’s loneliness. Husband’s cynical hostility, however, is associated with his own loneliness, but not his wife’s loneliness. We did not find evidence for significant gender differences between husbands’ and wives’ actor and partner paths. However, we did find evidence that the relationship between one’s own cynical hostility and loneliness, and a spouse’s cynical hostility and loneliness manifests differently for wives and husbands. For example, we found that the paths between (a) husbands’ cynical hostility and wives’ loneliness and (b) wives’ cynical hostility and wives’ loneliness significantly differed. Husbands, on the other hand, did not have significant differences between (a) wives’ cynical hostility and husbands’ loneliness or (b) husbands’ cynical hostility and husbands’ loneliness, implying that both a husband’s cynical hostility and his wife’s cynical hostility play a similar role in his loneliness.

This finding is in line with previous studies regarding how wives often maintain the emotional climate in heterosexual marriages (Gottman, 1994). Women may be more expressive about their cynical hostility as compared to their husbands, as they tend to express more emotions than men (Simon & Nath, 2004). Prior research has also consistently demonstrated that wives are more apt to exhibit negative affect, and that gender difference in expressing emotions within a marriage does not alter over the life course (Carstensen et al., 1995). Therefore, husbands in heterosexual marriages may be more susceptible to experiencing cynical hostility expressed by their wives. This may be related to husband’s loneliness as it may be harder for him to find intimacy in such relationship and should be explored in future research. Women tend to be less reliant on their husbands to create and maintain social relationships (Davidson, 2004; Okun & Keith, 1998), and having social relationships is linked to lower levels of loneliness (Hawkley & Kocherginsky, 2018). Women’s greater social independence may make them less vulnerable to their husbands’ cynical hostility than vice versa, as men, more than women, tend to nominate the spouse as the closest person to them (Fuhrer & Stansfeld, 2002).

Findings for Indirect Effects of Friendship

To explain the associations between cynical hostility and loneliness, we tested the indirect effects of friendship support, strain, and contact. We did not find that friendship support, strain, or contact mediated any associations between spouses’ cynical hostility and individuals’ loneliness. However, we did find that mediation occurred between individuals’ cynical hostility and loneliness for women.

For women, we found that their contact with friends and support from friends were significant mediators between their own cynical hostility and loneliness. It is possible that women with a higher level of cynical hostility have greater difficulty maintaining and expanding social networks. This may, in turn, be associated with a higher level of loneliness. Perhaps it is the perception of others as a source of wrongdoing, a key component in cynical hostility, that makes it difficult for women to maintain high levels of contact with, and support from friends. It is also possible that cynical hostility may decrease the number of friends who are willing to socialize and provide support to women, leaving them with less rewarding social relationships than they desire. These suggestions are also in line with previous studies finding negative associations between cynical hostility and social support (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2008). The deficits in contact and support of women with high levels of cynical hostility, and their links to loneliness highlight their potential vulnerability (Curtis & Jones, 2020; Segel-Karpas & Ayalon, 2019).

In contrast, we did not find that for men, friendship factors mediated the relationship between own cynical hostility and loneliness. It is possible that men rely more heavily on their spouses for social interaction and support (Fuhrer & Stansfeld, 2002). Hence, their spouses’ cynical hostility may be related to their own loneliness, but not necessarily via husbands’ friendships. Wives are more likely to be viewed as “kin-keepers” in their families, meaning that they are likely to be the individuals who are helping to maintain contact with external social networks (Hagestad, 1986). Husbands are more apt to have couple-oriented friendship networks (Davidson, 2004). Therefore, wives’ cynical hostility may be more likely to be associated with their husbands’ loneliness rather than the opposite, as wives who are high in cynical hostility may be less willing to initiate social activities.

Prior research has also found that women are more likely to rely on both social support within and beyond the marriage to be protected from loneliness, whereas men are more likely to be protected from loneliness due to their marriage (Dykstra & de Jong Gierveld, 2004). It is possible that, for men, relationship with a wife with a higher level of cynical hostility may be characterized by lower levels of intimacy. Wives’ inability to trust others and their perception that others are a source of potential risk may hinder their ability to be emotionally close and dependent on others (Segel-Karpas & Ayalon, 2019). Therefore, they may be less likely to offer their spouses the warmth and attachment they desire in the marital relationship, which could, in turn, be linked to spouse’s greater loneliness. Furthermore, those who have higher levels of cynical hostility may also perceive their spouse as less friendly (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2008) and more demanding, resulting in greater marital strain and higher levels of loneliness. Our initial analysis suggests that, indeed, husband’s own cynical hostility is connected to loneliness through his experience of marital strain. Finally, it is also possible that wives who are high in cynical hostility may be less willing to engage in joint activities with their husbands. These potential mechanisms should be explored in future studies.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be addressed. Despite research suggesting that long married counterparts enjoy joint friendships (e.g., Kalmijn, 2003), spouses’ joint or separate networks were not assessed in the HRS. Future research could use methods appropriate for the estimation of networks, and directly examine how spouse’s cynical hostility shapes partner’s contact with social counterparts. Second, cynical hostility was only measured twice in the HRS, thus limiting our ability to examine long-term effects and fluctuations. Moreover, while numerous studies have examined loneliness across the life course (Victor & Yang, 2012), relatively little is known about how the experience of cynical hostility differs between younger and older adults. Future research could test cynical hostility and loneliness in younger samples. Finally, cynical hostility may shape other relationships, first and foremost, the relationship with one’s family. Individuals with a higher level of cynical hostility may be less able to experience security and intimacy in their close relationships. Future research could examine hostility within the family, focusing on how hostility affects dyadic processes between partners, or between parents and children.

Despite these limitations, the study adds to the relatively little body of research examining the relationship between two cognitive schemas with important health and well-being implications. Despite the strong theoretical grounding connecting cynical hostility and loneliness (Segel-Karpas & Ayalon, 2019), little is known about their reciprocal effects in general, and the interplay between cynical hostility and loneliness in the context of social relationships. This study contributes by testing the toll cynical hostility takes not only on individuals’, but also on spouses’, perceived social relationships.

Conclusion

Practically, the results of this study suggest that, for those who are married, the couple might need to be considered as the target unit in interventions aimed at reducing loneliness in cases where a husband is experiencing loneliness. In such cases, examining the wife’s attitudes and behaviors could be helpful. Addressing the wife’s cynical hostility, perhaps through programming or counseling, may indirectly help her husband to overcome loneliness. Additionally, addressing wife’s cynical hostility may help her secure greater contact with friends and more support, and thus, reduce her own loneliness. Considering that interventions targeting social cognitions tend to have the greatest decreases in loneliness (Masi et al., 2011), targeting cynical hostility in interventions, which may be viewed as a social cognition, could be of importance for couples and individuals.

Supplementary Material

Funding

The Health and Retirement Study was sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant NIA U01AG009740).

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Acknowledgment

The Health and Retirement Study was conducted by the University of Michigan. The data are available online. The manuscript was pre-registered at the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/5cx37/.

References

- Ayalon L., Shiovitz-Ezra S., & Palgi Y (2013). Associations of loneliness in older married men and women. Aging & Mental Health, 17(1), 33–39. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2012.702725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barefoot J. C., Beckham J. C., Haney T. L., Siegler I. C., & Lipkus I. M (1993). Age differences in hostility among middle-aged and older adults. Psychology and Aging, 8(1), 3–9. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.8.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N., & Eckenrode J (1991). Social relationships, personality, and anxiety during a major stressful event. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(3), 440–449. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.3.440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummett B. H., Barefoot J. C., Feaganes J. R., Yen S., Bosworth H. B., Williams R. B., & Siegler I. C (2000). Hostility in marital dyads: Associations with depressive symptoms. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 23(1), 95–105. doi: 10.1023/a:1005424405056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen L. L., Gottman J. M., & Levenson R. W (1995). Emotional behavior in long-term marriage. Psychology and Aging, 10(1), 140–149. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.10.1.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., & Feeley T. H (2014). Social support, social strain, loneliness, and well-being among older adults: An analysis of the Health and Retirement Study. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 31(2), 141–161. doi: 10.1177/0265407513488728 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. Y., Gilligan S., Coups E. J., & Contrada R. J (2005). Hostility and perceived social support: Interactive effects on cardiovascular reactivity to laboratory stressors. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 29(1), 37–43. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2901_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook W. W., & Medley D. M (1954). Proposed hostility and Pharisaic-virtue scales for the MMPI. Journal of Applied Psychology, 38(6), 414–418. doi: 10.1037/h0060667 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa P. T. Jr, Zonderman A. B., McCrae R. R., & Williams R. B. Jr (1986). Cynicism and paranoid alienation in the Cook and Medley HO Scale. Psychosomatic Medicine, 48(3-4), 283–285. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198603000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis S. R., & Jones D. N (2020). Understanding what makes dark traits “vulnerable”: A distinction between indifference and hostility. Personality and Individual Differences, 160, 109941. doi: 10.1016/J.PAID.2020.109941 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson K. (2004). “Why can’t a man be more like a woman?”: Marital status and social networking of older men. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 13(1), 25–43. doi: 10.3149/jms.1301.25 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drageset J. (2004). The importance of activities of daily living and social contact for loneliness: A survey among residents in nursing homes. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 18(1), 65–71. doi: 10.1111/j.0283-9318.2003.00251.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra P. A., & de Jong Gierveld J (2004). Gender and marital-history differences in emotional and social loneliness among Dutch older adults. Canadian Journal on Aging = La revue canadienne du vieillissement, 23(2), 141–155. doi: 10.1353/cja.2004.0018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermer A. E., & Proulx C. M (2020). Social support and well-being among older adult married couples: A dyadic perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 37(4), 1073–1091. doi: 10.1177/0265407519886350 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ermer A. E., Segel-karpas D., & Benson J. J (2020). Loneliness trajectories and correlates of social connections among older adult married couples. Journal of Family Psychology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/fam0000652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrer R., & Stansfeld S. A (2002). How gender affects patterns of social relations and their impact on health: A comparison of one or multiple sources of support from “close persons.” Social Science & Medicine, 54(5), 811–825. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00111-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman J. M. (1994). Why marriages success or fail. Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Graham J. E., Robles T. F., Kiecolt-Glaser J. K., Malarkey W. B., Bissell M. G., & Glaser R (2006). Hostility and pain are related to inflammation in older adults. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 20(4), 389–400. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagestad G. O. (1986). Dimensions of time and the family. American Behavioral Scientist, 29(6), 679–694. doi: 10.1177/000276486029006004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley L. C., & Kocherginsky M (2018). Transitions in loneliness among older adults: A 5-year follow-up in the national social life, health, and aging project. Research on Aging, 40(4), 365–387. doi: 10.1177/0164027517698965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J., Smith T. B., Baker M., Harris T., & Stephenson D (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J., Smith T. W., & Uchino B. N (2008). Can hostility interfere with the health benefits of giving and receiving social support? The impact of cynical hostility on cardiovascular reactivity during social support interactions among friends. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 35(3), 319–330. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9041-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppmann C., & Gerstorf D (2009). Spousal interrelations in old age—a mini-review. Gerontology, 55(4), 449–459. doi: 10.1159/000211948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh N., & Hawkley L (2018). Loneliness in the older adult marriage: Associations with dyadic aversion, indifference, and ambivalence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 35(10), 1319–1339. doi: 10.1177/0265407517712480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M. E., Waite L. J., Hawkley L. C., & Cacioppo J. T (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Research on Aging, 26(6), 655–672. doi: 10.1177/0164027504268574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxhold O., Miche M., & Schüz B (2014). Benefits of having friends in older ages: Differential effects of informal social activities on well-being in middle-aged and older adults. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(3), 366–375. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn M. (2003). Shared friendship networks and the life course: An analysis of survey data on married and cohabiting couples. Social Networks, 25(3), 231–249. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8733(03)00010-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn M., & Bernasco W (2001). Joint and separated lifestyles in couple relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(3), 639–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00639.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lepore S. J. (1995). Cynicism, social support, and cardiovascular reactivity. Health Psychology, 14(3), 210–216. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.3.210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi C. M., Chen H. Y., Hawkley L. C., & Cacioppo J. T (2011). A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(3), 219–266. doi: 10.1177/1088868310377394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L. K., & Muthén B. O (2017). Mplus user’s guide. 8th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Okun M. A., & Keith V. M (1998). Effects of positive and negative social exchanges with various sources on depressive symptoms in younger and older adults. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 53(1), P4–20. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.1.p4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peplau L. A., & Perlman D (1982). Perspectives on loneliness. In Peplau L. A. & Perlman D. (Eds.), Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. Wiley-Interscience. doi: 10.2307/2068915 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M., & Sorensen S (2001). Influences on loneliness in older adults: A meta-analysis. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 23(4), 245–266. doi: 10.1207/S15324834BASP2304_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K. J., & Hayes A. F (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segel-Karpas D., & Ayalon L (2019). Loneliness and hostility in older adults: A cross-lagged model. Psychology and Aging, 35(2), 169–176. doi: 10.1037/pag0000417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon R. W., & Nath L. E (2004). Gender and emotion in the United States: Do men and women differ in self-reports of feelings and expressive behavior? American Journal of Sociology, 109(5), 1137–1176. doi: 10.1086/382111 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. W.(1994). Concepts and methods in the study of anger, hostility, and health. In A. W. Siegman and T. W. Smith (Eds.), Anger, hostility, and the heart (pp. 23–42). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. W., Glazer K., Ruiz J. M., & Gallo L. C (2004). Hostility, anger, aggressiveness, and coronary heart disease: An interpersonal perspective on personality, emotion, and health. Journal of Personality, 72(6), 1217–1270. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00296.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes J. E. (2016). Two-wave dyadic analysis of marital quality and loneliness in later life: Results from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing. Research on Aging, 39(5), 635–656. doi: 10.1177/0164027515624224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valtorta N. K., Kanaan M., Gilbody S., Ronzi S., & Hanratty B (2016). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart (British Cardiac Society), 102(13), 1009–1016. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor C. R., & Yang K (2012). The prevalence of loneliness among adults: A case study of the United Kingdom. The Journal of Psychology, 146(1–2), 85–104. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2011.613875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., & Penning M (2015). Immigration and loneliness in later life. Ageing and Society, 35(1), 64–95. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X13000470 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.