Abstract

Objectives

Beliefs about aging can contribute to health and well-being in older adults. Feeling generative, or that one is caring for and contributing to the well-being of others, can also impact health and well-being. In this study, we hypothesized that those with more positive expectations regarding aging (ERA) in the mental health domain would report greater levels of perceived social support (PSS) and lower levels of loneliness in response to a generativity intervention (vs control condition).

Method

Participants in this study (n = 73, 100% female) were randomly assigned to a 6-week generativity condition, which involved writing about life experiences and sharing advice with others, or to a control condition, which involved writing about neutral topics. Pre- and postintervention, PSS, and feelings of loneliness were measured.

Results

Those in the generativity condition with more positive ERA in the mental health domain reported greater PSS and lower loneliness postintervention.

Discussion

These results highlight the importance of psychological factors, such as ERA, in moderating the efficacy of interventions to promote social well-being in older adults.

Keywords: Beliefs, Social psychology of aging, Social support

I hate that word [anti-aging]! It should be something positive, like pro-aging.

– Julia Louis-Dreyfus, actress

Beliefs about aging are an important contributor to behavioral and health outcomes in older adults. For example, more positive beliefs about aging are linked with better health and well-being, including increased longevity (Levy, Slade, Kunkel, & Kasl, 2002; Warmoth, Tarrant, Abraham, & Lang, 2016). Beliefs about aging can also impact social well-being. Expecting to be lonelier as a function of age and stereotyping old age as a time of loneliness is associated with feeling lonelier almost a decade later (Pikhartova, Bowling, & Victor, 2016). Older adults with more positive expectations regarding aging (ERA) are also more likely to increase social engagement in the future (Menkin, Robles, Gruenewald, Tanner, & Seeman, 2016). Together, these findings suggest that having more positive ERA may play an important role in shaping older adults’ social well-being. In this study, we examined whether ERA influenced the effects of an intervention aimed at increasing social well-being.

In addition to beliefs about aging, another psychosocial factor that may influence social well-being in older adults is generativity, or the feeling that one is contributing to others, particularly younger generations. Indeed, generativity, which involves the “need to be needed” (McAdams & De St Aubin, 1992) through a desire to be useful to others, has been associated with greater psychological and social well-being (Keyes & Ryff, 1998), social support (Hart, McAdams, Hirsch, & Bauer, 2001), and prosocial behavior (Cox, Wilt, Olson, & McAdams, 2010). Furthermore, many older adults experience loneliness due to a loss of meaningful social engagement (Smith, 2012), suggesting low levels of generativity and social usefulness may contribute to subjective feelings of social isolation in this population. Importantly, providing opportunities to participate in generative activity may reduce social isolation in older adults (Carlson, Seeman, & Fried, 2000). Improving such social outcomes in older adults is a public health priority, given that greater loneliness and decreased social support are associated with greater morbidity and mortality (Blazer, 1982; Perissinotto, Stijacic Cenzer, & Covinsky, 2012).

Thus, increasing generativity via an intervention may improve older adults’ social well-being, suggesting that generativity interventions may be an effective tool for improving loneliness and perceived social support (PSS) in older adults. Specifically, previous work has found that a volunteering intervention involving intergenerational contact can increase generativity (Gruenewald et al., 2016) and improve PSS (Fried et al., 2004) in older adults. However, this type of “high intensity” intervention may not be a proper fit for all older adults, particularly ones with limitations preventing them from participating in intensive volunteering. As such, there is a need to develop generativity interventions which may impact social well-being but may also be more accessible, such as a writing-based intervention.

Furthermore, given the influence of beliefs about aging on social outcomes, it is possible that positive views about aging may also influence how older adults respond to psychological interventions. Thus, it is possible that a generativity intervention may have its most salutary effects on social well-being in older individuals with positive ERA. In support of this notion, psychological interventions are more effective for those who are motivated to and expect to benefit from the activity (Lyubomirsky & Layous, 2013). Furthermore, stereotype embodiment theory (Levy, 2009) suggests that stereotypes and beliefs about aging can lead to differential outcomes via self-fulfilling prophecies (e.g., engagement with the generativity intervention) and behaviors (e.g., self-efficacy regarding the generativity intervention).

As such, the goal of this study was to test whether ERA, specifically in the mental health domain, moderated the effect of a generativity intervention on social well-being, as a secondary analysis on a previous data set. We hypothesized that the generativity intervention would lead to greater social well-being for those with more positive ERA.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Detailed information about participants and procedures are described elsewhere (reporting the primary outcomes of the study; Moieni et al., 2020), as well as in the Supplementary Material, but are also summarized here. In brief, participants were healthy women aged 60 and older screened for feeling low in current generative achievement relative to their generative desire (Gruenewald et al., 2016).

All participants (n = 78 females) were randomized into either a 6-week generativity or control writing condition and were told that the study was investigating the relationship between writing about experiences and health. As described previously (Moieni et al., 2020) and the Supplementary Material, 5 participants did not complete the study, leaving a total final sample of 73 female participants (mean age 70.9 ± 6.5 years; 80.8% white; 35 in the control condition, 38 in the generativity condition). The sample size was determined for the primary aims of the study (Moieni et al., 2020); further details are available in the Supplementary Material.

Participants in the generativity condition wrote weekly about their life experiences and shared their wisdom and advice (for middle-aged adults) in response to topics such as: “What are some of the most important lessons you feel you have learned over the course of your life? If a middle-aged person asked you “what have you learned in your ____ years in this world,” what would you tell him or her?....” In order to provide an audience for participants’ generative action, participants in the generativity condition were informed that their responses would be collected, made anonymous, and published into a book or website intended to help middle-aged adults. For the full listing of the prompts, see Supplementary Material.

Participants in the control condition were not told that their writings would be shared and wrote about neutral topics such as: “In the space provided below, please describe what you had for lunch today—what it looked like, how it tasted…. In your writing, please try to focus on the details of what you ate, how it looked, and how it tasted, rather than on who you were with or what you were thinking about during this time….”

All participants provided written consent. All procedures were approved by the UCLA Human Subjects Protection Committee (IRB#14-000811). The general design, as well as the primary outcomes, of the study (Moieni et al., 2020), was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02472379). The secondary analyses presented here were not preregistered.

Self-report Measures

ERA Survey

The ERA Survey (Mental Health Domain), measured at preintervention, is a valid, reliable (α = .64) scale to assess participants’ beliefs about mental health as a function of age (Sarkisian, Steers, Hays, & Mangione, 2005).1 Participants were presented with four statements regarding beliefs about aging and mental health, including two items relevant to the social domain (e.g., “being lonely is just something that happens when people get old”; all four items in Supplementary Material).

Social Provisions Scale

The Social Provisions Scale, measured pre- and postintervention, is a valid, reliable (α = .90) scale to assess multiple domains of PSS, such as feelings of attachment and social integration (Cutrona, 1984; Cutrona & Russell, 1987; e.g., “I feel a strong emotional bond with at least one other person”).

UCLA Loneliness Scale

The UCLA Loneliness Scale, measured pre- and postintervention, is a valid, reliable (α = .92) scale to assess loneliness (Russell, 1996) (e.g., “how often do you feel alone?”). Loneliness and perceptions of social support were significantly correlated with each other (at preintervention, r = −.71, p < .001) but represent distinct constructs with separate, rich literatures and thus were both examined as social well-being outcomes.

General Analytic Strategy

In order to test the moderating effect of ERA on PSS and loneliness, the PROCESS macro for SPSS was used (Hayes, 2012). To examine whether ERA moderated the effect of the intervention on PSS and loneliness, we tested the interaction of condition (generativity vs control) and ERA on PSS and loneliness postintervention, controlling for preintervention values.

Results

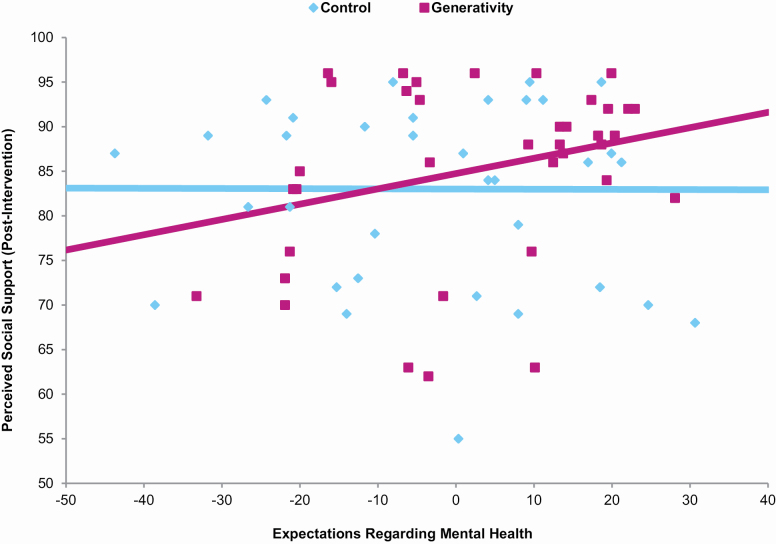

At baseline, the two groups were not different in ERA, loneliness, or PSS (ps > .2). As hypothesized, there was a significant interaction between condition (generativity vs control) and ERA, such that more positive ERA predicted greater PSS postintervention for those in the generativity condition (vs control; Figure 1; B = .174, SE = .070, 95% confidence interval [CI] = [.034, .313], t = 2.48, p < .05). Analysis of conditional effects revealed that higher ERA predicted improvements in PSS within the generativity condition (B = .172, SE = .052, 95% CI = [.068, .276], t = 3.30, p < .01), but not in the control condition (B = −.002, SE = .048, 95% CI = [−.097, .093], t = −.042, p > .9).

Figure 1.

Relationship between expectations regarding aging (ERA) in the mental health domain and perceptions of social support (PSS). ERA scores, displayed regression lines, and all statistical analyses adjusted for preintervention values on PSS.

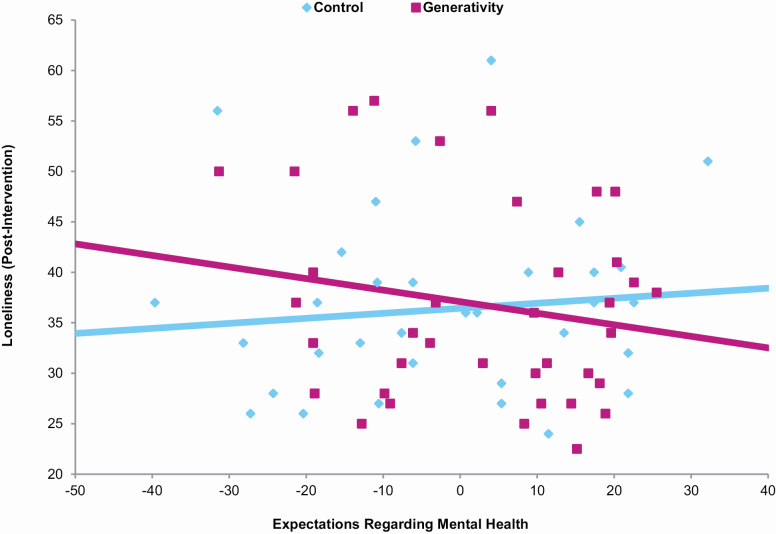

This same pattern of results held true for feelings of loneliness. As hypothesized, there was a significant interaction between condition (generativity vs control) and ERA, such that more positive ERA predicted lower feelings of loneliness postintervention for those in the generativity condition (vs control; Figure 2; B = −.164, SE = .055, 95% CI = [−.274, −.055], t = −3.00, p < .01). Analysis of conditional effects revealed that higher ERA predicted improvements in loneliness within the generativity condition (B = −.115, SE = .042, 95% CI = [−.198, −.031], t = −2.74, p < .01), but not in the control condition (B = .050, SE = .039, 95% CI = [−.027, .127], t = 1.29, p > .2).

Figure 2.

Relationship between expectations regarding aging (ERA) in the mental health domain and feelings of loneliness. ERA scores, displayed regression lines, and all statistical analyses adjusted for preintervention values on feelings of loneliness.

Discussion

Here, we tested whether ERA moderated the effect of a novel writing-based generativity intervention on social well-being. Indeed, there was a significant moderation effect of ERA on PSS and loneliness. Those in the generativity condition with more positive ERA in the mental health domain showed greater PSS and lower feelings of loneliness after the intervention.

This study provides insight into an important question in intervention development: for whom is the intervention most beneficial? In regards to the effects of a writing-based generativity intervention on social well-being, ERA appear to play a role in deriving benefit. While no work has examined this question directly, related prior work supports this finding. For example, participants with greater motivation to become happier—who expect a positive psychology intervention may lead to benefits—show greater increases in well-being (Lyubomirsky, Dickerhoof, Boehm, & Sheldon, 2011). Although participants in this study were not informed that the intervention was a well-being–enhancing intervention and thus could not explicitly expect benefits, their preexisting ERA may have played a similar role.

There are several pathways through which these beliefs about aging may impact social well-being in a generativity intervention. As suggested by stereotype embodiment theory, one way in which stereotypes of aging can lead to negative outcomes is by creating expectations that act as self-fulfilling prophecies (Levy, 2009). Thus, participants in the generativity intervention with more negative ERA may not engage as much in an intervention aiming to increase feelings of social usefulness due to their preexisting expectations. As a result of this, these participants may not derive as much benefit, leading to less favorable social well-being as a result of the intervention.

Stereotype embodiment theory also suggests that behavior may be another pathway through which beliefs and stereotypes about aging may impact outcomes (Levy, 2009). For example, priming negative age stereotypes can impair self-efficacy (Levy, Hausdorff, Hencke, & Wei, 2000). In the context of this study, impairments in self-efficacy as a result of more negative ERA may be another pathway for the moderating effects. Those in the generativity condition with lower ERA may feel that they are less effective at providing advice to others, and this lower self-efficacy may also inhibit feelings of social usefulness and generativity, driving the moderating effects.

A few limitations should be considered. First, this study was conducted in a very selective sample, exclusively female and mostly white, as well as one limited to older women who had access to the Internet and a computer. This suggests that future studies should examine these effects in more representative samples. Future studies should also directly examine the proposed mechanisms for the effects, such as examining whether participants’ self-efficacy with regards to the generativity writing task is affected as a function of ERA. Additionally, the experimental component of this study was the generativity intervention; beliefs about aging were not directly manipulated and thus causal influences of ERA on social well-being cannot be determined.

The study also had several strengths, including the development of a novel generativity intervention for older adults. Furthermore, this is a low-cost, low-effort intervention and thus potentially accessible to large segments of the older adult population. The intervention also included measures of both PSS and loneliness, allowing effects to be examined across multiple social outcomes, which are both significant contributors to health outcomes in older adults (Blazer, 1982; Perissinotto et al., 2012). Furthermore, examining moderators of interventions is an important area of investigation, allowing us to understand who may benefit the most from future interventions (Lyubomirsky & Layous, 2013). Finally, these findings may ultimately have large-scale public health impacts, as they suggest that altering personal and societal views of aging may interact with other processes to impact social well-being. However, altering negative views of aging is complex, with few effective interventions supported by evidence thus far (Kotter-Grühn, 2015). Thus, while these results theoretically may have broad clinical implications, further research is needed to identify effective, long-lasting interventions to alter negative views of aging.

In conclusion, this study provides valuable information about the effect of a novel writing-based intervention on social well-being in older adults. Those with more positive ERA, specifically in the mental health domain, may derive the most benefit from such an intervention. Thus, interventions aiming to improve social well-being through generativity may also need to alter ERA in order to maximize impact.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the staff of the UCLA Clinical and Translational Research Center, staff of the UCLA Pathology Research Portal, staff of the UCLA Inflammatory Biology Core (including Stephanie Esquivel, Nancy Herrera-Morales, Nabil Aziz, Robert Bang, and Christian Perez), and staff of the UCLA Social Genomics Core. Additionally, we would like to thank Kanika Shirole, Nina Sadeghi, Carmen Carrillo, Richard Olmstead, Heather McCreath, and Kate E. Byrne Haltom for their assistance with various aspects of the project. Thank you to members, past and present, of the UCLA SCAN labs for providing valuable feedback on several aspects of this study. Finally, thank you to Spencer Bujarski, PhD, for providing statistical consulting.

The raw data supporting the conclusions are available by request by contacting the corresponding author, Naomi Eisenberger, at neisenbe@ucla.edu. Data will be made available in this fashion because we did not ask our human subjects ahead of time if we could share the data. We will therefore make data (stripped of subjects’ identifying information) available upon request to be conservative toward protecting subjects.

Footnotes

Due to technical issues, one of the items in the mental health domain of the ERA Survey was from the 38-item version of the scale (Sarkisian, Hays, Berry, & Mangione, 2002) rather than the intended 12-item version. The item in the 12-item scale that reads “as people get older they worry more” (Item 7) instead read “quality of life declines as people age.” Removing this item from the scale does not change the results of the analyses.

Funding

This work was supported by an R03 from the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health (R03AG049254 to N. I. Eisenberger). This project also was financially supported by the UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Institute (UL1TR000124; Seed Grant) and the UCLA Older Adults Independence Center (5P30AG028748; Rapid Pilot Grant). Additionally, the first author was supported by a predoctoral NRSA fellowship from the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health (F31AG048668) and a postdoctoral fellowship from the UCLA Cousins Center for Psychoneuroimmunology. The aforementioned funders provided financial support for the study, but they were not involved in the conduct of the study in any other capacity (e.g., design, data collection, manuscript preparation, etc.).

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

References

- Blazer D. G. (1982). Social support and mortality in an elderly community population. American Journal of Epidemiology, 115, 684–694. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M. C., Seeman T., & Fried L. P (2000). Importance of generativity for healthy aging in older women. Aging (Milan, Italy), 12, 132–140. doi: 10.1007/bf03339899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox K. S., Wilt J., Olson B., & McAdams D. P (2010). Generativity, the big five, and psychosocial adaptation in midlife adults. Journal of Personality, 78, 1185–1208. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00647.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona C. E. (1984). Social support and stress in the transition to parenthood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 93, 378–390. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.93.4.378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona C. E., & Russell D. W (1987). The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress. Advances in Personal Relationships, 1(1), 37–67. [Google Scholar]

- Fried L. P., Carlson M. C., Freedman M., Frick K. D., Glass T. A., Hill J.,…Zeger S (2004). A social model for health promotion for an aging population: Initial evidence on the Experience Corps model. Journal of Urban Health, 81, 64–78. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald T. L., Tanner E. K., Fried L. P., Carlson M. C., Xue Q. L., Parisi J. M.,…Seeman T. E (2016). The Baltimore experience corps trial: Enhancing generativity via intergenerational activity engagement in later life. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71, 661–670. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart H. M., McAdams D. P., Hirsch B. J., & Bauer J. J (2001). Generativity and social involvement among African Americans and White adults. Journal of Research in Personality, 35(2), 208–230. doi: 10.1006/jrpe.2001.2318 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. Retrieved from http://afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf

- Keyes C. L. M., & Ryff C. D (1998). Generativity in adult lives: Social structural contours and quality of life consequences. In D. P. McAdams & E. de St. Aubin (Eds.), Generativity and adult development: How and why we care for the next generation (p. 227–263). Washington DC: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/10288-007 [Google Scholar]

- Kotter-Grühn D. (2015). Changing negative views of aging: Implications for intervention and translational research. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 35(1), 167–186. doi: 10.1891/0198-8794.35.167 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levy B. (2009). Stereotype embodiment: A psychosocial approach to aging. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18, 332–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01662.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy B. R., Hausdorff J. M., Hencke R., & Wei J. Y (2000). Reducing cardiovascular stress with positive self-stereotypes of aging. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 55, P205–P213. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.4.p205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy B. R., Slade M. D., Kunkel S. R., & Kasl S. V (2002). Longevity increased by positive self-perceptions of aging. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 261–270. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.2.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S., Dickerhoof R., Boehm J. K., & Sheldon K. M (2011). Becoming happier takes both a will and a proper way: An experimental longitudinal intervention to boost well-being. Emotion, 11(2), 391. doi: 10.1037/a0022575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S., & Layous K (2013). How do simple positive activities increase well-being? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(1), 57–62. doi: 10.1177/0963721412469809 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams D. P., & De St Aubin E (1992). A theory of generativity and its assessment through self-report, behavioral acts, and narrative themes in autobiography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62(6), 1003. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.62.6.1003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Menkin J. A., Robles T. F., Gruenewald T. L., Tanner E. K., & Seeman T. E (2016). Positive expectations regarding aging linked to more new friends in later life. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72(5), 771–781. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moieni M., Irwin M. R., Seeman T. E., Robles T. F., Lieberman M. D., Breen E. C.,…Eisenberger N. I (2020). Feeling needed: Effects of a randomized generativity intervention on well-being and inflammation in older women. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 84, 97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perissinotto C. M., Stijacic Cenzer I., & Covinsky K. E (2012). Loneliness in older persons: A predictor of functional decline and death loneliness in older persons. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172, 1078–1083. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pikhartova J., Bowling A., & Victor C (2016). Is loneliness in later life a self-fulfilling prophecy? Aging & Mental Health, 20, 543–549. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1023767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D. W. (1996). UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66, 20–40. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisian C. A., Hays R. D., Berry S., & Mangione C. M (2002). Development, reliability, and validity of the expectations regarding aging (ERA-38) survey. The Gerontologist, 42, 534–542. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.4.534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisian C. A., Steers W. N., Hays R. D., & Mangione C. M (2005). Development of the 12-item expectations regarding aging survey. The Gerontologist, 45, 240–248. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.2.240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. M. (2012). Toward a better understanding of loneliness in community-dwelling older adults. The Journal of Psychology, 146, 293–311. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2011.602132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warmoth K., Tarrant M., Abraham C., & Lang I. A (2016). Older adults’ perceptions of ageing and their health and functioning: A systematic review of observational studies. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 21, 531–550. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2015.1096946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.