Abstract

A 75-year-old man was admitted with a 3-month history of worsening diarrhoea and weight loss. He was on long-term immunosuppression following cardiac transplantation. Investigations revealed herpes simplex oesophagitis and stool samples were positive for norovirus. Treatment with acyclovir and nitazoxanide resulted in a complete resolution of symptoms. Norovirus is a common cause of infectious gastroenteritis, but immunosuppressed patients may present with chronic diarrhoea rather than an acute illness. This case highlights the importance of a low clinical threshold for testing for norovirus infection in immunocompromised patients.

Keywords: gastroenterology, infection (gastroenterology), infectious diseases

Background

Chronic diarrhoea in an immunocompromised patient can have many causes with the potential for significant complications including malabsorption, dehydration and acute kidney injury.1

Case presentation

A 75-year-old man presented with a 3-month history of worsening diarrhoea and weight loss. The stool had a liquid consistency without blood (type 6 and type 7 based on the Bristol Stool Chart)2 and a 24-hour frequency of up to five times, worse in the evening and overnight. The patient had lost 10 kg in 8 weeks, weighing 49 kg on admission, representing a 17% weight loss. Other symptoms included dyspepsia and odynophagia in the absence of nausea, vomiting or fever. Clinical examination revealed oral aphthous ulceration but no hepatosplenomegaly. The patient denied any seafood consumption before developing symptoms or any contact with children from an educational setting. There was no history of communal activities such as using a swimming pool.

In 1999, he underwent a cardiac transplant for post-myocardial infarction heart failure and was maintained on long-term immunosuppression with mycophenolate mofetil and ciclosporin. Two months prior to admission, the patient had experienced an episode of acute rejection and was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone. The immunosuppressive regime was intensified with the addition of prednisolone and the substitution of ciclosporin by tacrolimus because of fluctuating drug levels. His medical history also included small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (2012), cholecystectomy (2014) and stage 4 chronic kidney disease (estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) 27).

The patient was a non-smoker and abstained from alcohol after the cardiac transplant. Relevant travel history included a 5-year period living in Vietnam (returning 4 years earlier) and a recent trip to Mexico (3 months prior to symptoms).

Investigations

Investigation for coeliac disease, thyroid disorders, neuroendocrine tumour and HIV were all negative. Multiple stool cultures were negative for Clostridium difficile, Campylobacter, Salmonella and Escherichia coli. Faecal calprotectin was low (61 μg/g), indicating an absence of gastrointestinal (GI) neutrophilic inflammation. Faecal elastase for pancreatic insufficiency and 7-alpha-hydroxycholestenone testing for bile salt malabsorption were also normal. A positive hydrogen breath test suggested small intestinal bacterial overgrowth.

Upper GI endoscopy revealed mild ulceration in the lower third of the oesophagus, antral gastritis and a normal duodenum. Immunohistochemistry revealed herpes simplex virus (HSV) oesophagitis. Gastric and duodenal biopsies were histologically normal.

A colonoscopy showed diverticulosis with no associated inflammation and an ileocaecal submucosal lesion. Colonic biopsies showed no evidence of a microscopic colitis and no cytomegalovirus inclusion bodies were identified. Epstein-Barr virus and HSV staining were negative. CT scanning of the chest, abdomen and pelvis to exclude neoplasia indicated that the ileocaecal lesion was an incidental lipoma.

With no improvement in symptoms and following advice from the infectious diseases team, further stool samples were tested. These were negative for rotavirus, adenovirus, ova, cysts and parasites, with a positive PCR test for norovirus.

Treatment

Initially, mycophenolate mofetil was stopped due to concerns that the diarrhoea was a side effect of this medication; however, there was no improvement in stool consistency. Tacrolimus was continued and the dose of prednisolone doubled to 10 mg once a day.

The patient was treated with 5 days of intravenous acyclovir (260 mg three times a day) for the HSV oesophagitis, resulting in a temporary resolution of his odynophagia. However, further mouth ulcers developed and mouth swabs identified HSV on PCR testing. Following consultation with an infectious diseases physician, intravenous acyclovir was restarted at an increased dose (610 mg two times a day) adjusted for improved renal function (eGFR >30) for a total of 21 days of treatment and a 3-month course of antiviral prophylaxis was commenced.

The patient also received treatment for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth with rifaximin at a dose of 550 mg two times a day for 2 weeks.

Unfortunately, he continued to lose weight with a documented further weight loss of 3 kg (49–46 kg, body mass index (BMI) 13.3). Oral nutritional supplements were ineffective and nasogastric feeding was poorly tolerated, the patient reporting profuse diarrhoea. Parenteral nutrition was started at this point but his diarrhoea did not improve.

After the identification of norovirus, infection control measures were put in place and supportive management initiated. However, his diarrhoea persisted, prompting further consideration of a specific therapy targeting norovirus. Ribavirin was considered but with a risk of rejection occurring in solid organ transplant recipients this treatment option was discounted. Instead, nitazoxanide was given for a total of 2 weeks following reports of successful clearance in renal transplant patients, despite a concern that it may exacerbate his diarrhoea.

Outcome and follow-up

Towards the end of the 2-week course of nitazoxanide, stool consistency improved until the patient was passing one formed stool per day (Bristol Stool Chart Type 4). Despite this symptomatic response, repeat stool samples remained positive for norovirus. Parenteral nutrition was provided for a total of 6 weeks with a gradual increase in albumin and body weight to 60 kg (BMI 18). The patient restarted a normal diet and tolerated this well, allowing discharge without parenteral nutrition.

Discussion

Chronic diarrhoea may result from bacterial, viral and parasitic infection as well as other causes which were considered in the differential diagnosis (table 1).

Table 1.

Causes of chronic diarrhoea

| Potential cause | Investigations performed in this case |

| Infection (including viral and parasitic) | Stool cultures/PCR |

| Neoplasia such as colorectal cancer or lymphoma | Important to exclude in this age group. Colorectal biopsies—benign. |

| Diverticular disease | Colonoscopy—diverticulae but no features of acute diverticulitis |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Low faecal calprotectin made this diagnosis less likely |

| Microscopic colitis | No evidence on colonic biopsies |

| Drugs including immunosuppressive medications | Mycophenolate mofetil commonly causes diarrhoea, stopped with no improvement in symptoms |

| Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth | Positive hydrogen breath test suggested this as a cause |

| Pancreatic insufficiency | Faecal elastase level normal |

| Coeliac disease | Normal duodenal biopsies |

| Thyroid disorders | TSH level normal |

| Bile acid malabsorption | 7-alpha-hydroxycholestenone normal |

| Cytomegalovirus infection | Cytomegalovirus inclusion bodies not identified on biopsy |

| HIV infection | Negative serology |

| Graft versus host disease (GVHD) | Diarrhoea is common in GVHD but the absence of dermatological symptoms and low incidence in solid organ transplant patients made this diagnosis less likely. Colorectal biopsies normal. |

| Functional—irritable bowel syndrome | Diagnosis of exclusion |

TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone.

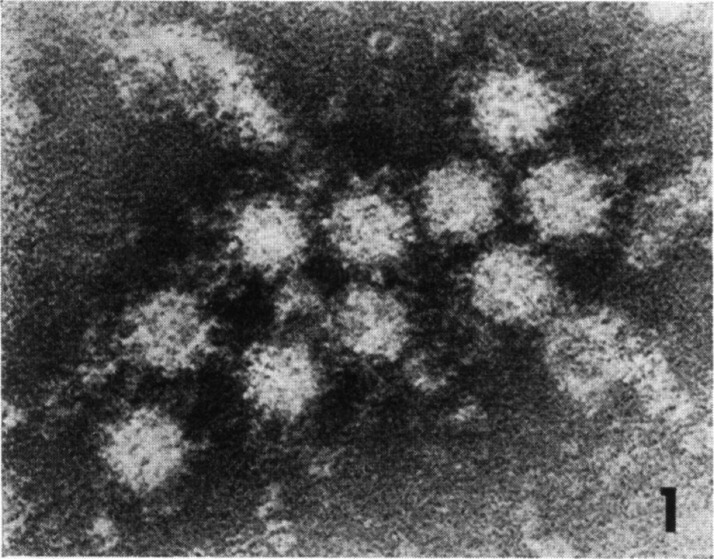

Norovirus (figure 1)3 is a common cause of infectious gastroenteritis, accounting for 90% of viral cases,4 and it frequently leads to outbreaks of diarrhoea and vomiting in healthcare settings.5 Norovirus has a high viral load in stool and vomit and a low infective dose will cause symptomatic infection highlighting its highly contagious nature.6 With an incubation period of 24–48 hours,7 infection typically causes a self-limiting gastroenteritis with individuals experiencing nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and diarrhoea over a period of 48–72 hours. The patient in this report experienced symptoms for a significantly longer duration and this influenced the initial investigations undertaken. Although symptoms may resolve after several days, norovirus may continue to be shed in the stool beyond 21 days with continued risk of faecal–oral transmission.8

Figure 1.

Electron microscopy of norovirus (adapted from Kapikian et al [3] with permission from American Society for Microbiology – License number 4974290226792, p1076).

Norovirus is diagnosed by PCR testing which is not routinely performed when stool samples are submitted for microbiological culture to exclude infections such as Escherichia coli and Campylobacter.9 Only after three negative microbiological cultures for bacterial causes was viral testing for norovirus testing performed. Earlier identification would have allowed quicker initiation of treatment.

Norovirus infection in immunocompromised patients may be more prolonged with respect to both symptoms and viral shedding.1 This patient reported several months of worsening diarrhoea but it is difficult to determine specifically when he may have acquired norovirus. It is possible that the episode of rejection requiring hospital admission and the intensification of his immunosuppressive medication contributed to the patient becoming infected with norovirus.

The prevalence of chronic norovirus infection is difficult to ascertain but it has been estimated at about 13% in patients with solid organ transplants.10 The virus may also be carried asymptomatically by immunosuppressed individuals.11 It has been suggested that in immunocompetent patients, antibody and cytotoxic T cell responses play a role in clearing the virus.12 This could explain why individuals with conditions such as common variable immunodeficiency or patients taking immunosuppressive medications may not clear the infection.

This patient was prescribed mycophenolate mofetil and this was stopped because of the drug’s side effects.13 Cessation of this drug followed liaison with the transplant team who advised an increased dose of tacrolimus based on trough samples. Decreasing the dose of prednisolone to improve the chances of clearing the norovirus infection was considered as studies have suggested reducing immunosuppression may be beneficial.14 However, there were concerns following the recent rejection episode that any reduction in immunosuppression may lead to a further episode of rejection.

Alternative treatment options were considered including the use of the antiviral agent ribavirin which in a small study by Woodward et al cleared norovirus in two out of five patients with common variable immunodeficiency enteropathy.12 However, ribavirin is associated with a risk of rejection in solid organ transplant recipient.15

The antiviral drug favipiravir was also considered since this is thought to cause norovirus mutations resulting in decreased infectivity.16 A case report describes chronic norovirus infection in a patient with common variable immunodeficiency enteropathy treated with favipiravir. Initial loading with favipiravir resulted in symptomatic improvement but the development of deranged liver function tests led to a suspension of treatment.16 Symptoms recurred and favipiravir was restarted at a lower dose with some improvement in diarrhoea. Limited supplies of the drug meant the treatment had to be stopped and symptoms returned.

The thiazolide anti-infective agent nitazoxanide is effective against anaerobic bacteria, protozoa and viruses and seemed to be the most promising.5 The mechanism of action against viruses is thought to involve targeting the cellular pathways involved in the synthesis of viral proteins. Nitazoxanide is given orally at a dose of 500 mg two times daily and the drug is metabolised to tizoxanide in the gut.5 Side effects include abdominal pain, nausea and diarrhoea.14 Ghusson et al reported that three patients with renal transplants successfully cleared norovirus after treatment with nitazoxanide.14 A clinical trial by Rossignol and El-Gohary found a 3-day course of treatment with nitazoxanide significantly reduced illness duration in immunocompetent patients with a reduced time for resolution of symptoms (1.5 days in the nitazoxanide group and 2.5 days in the placebo group).5 The patient in this report was given nitazoxanide 500 mg twice a day for 2 weeks with symptomatic improvement towards the end of the course. Side effects of his treatment included increased urinary frequency and itchy palms which have been described.

Although there is presently no licensed vaccine against norovirus, several ongoing preclinical and clinical trials are evaluating different vaccines. A phase II clinical trial of a bivalent vaccine and a phase I clinical trial of an oral vaccine are underway.11 A vaccine could potentially reduce the risk of immunosuppressed patients developing norovirus.

Conclusions

The frequency of chronic norovirus infection in solid organ transplant patients is probably underestimated with significant morbidity. It is important to consider norovirus as a cause of diarrhoea in patients who are immunosuppressed and refer promptly for specialist investigations and treatment. The use of drugs such as nitazoxanide could help these patients clear their norovirus infections; however, further research in the form of a blinded multicentre randomised control trial assessing the efficacy of this treatment would be beneficial.

Patient’s perspective.

I was admitted to hospital as I was experiencing substantial weight loss, regular diarrhoea and weakness. After a day of assessment, I was admitted to the GI ward for further evaluation and treatment.

During the twelve weeks in the GI ward I was subjected to many tests of both stool and blood including a colonoscopy and endoscopy. During the first month of treatment I was listless and lacked energy and interest in what was going on around me. I was continuing to lose weight.

When it was determined that I was suffering from norovirus a course of treatment was initiated taking into account that my immune system was suppressed because of my heart transplant. I was also being fed intravenously as my digestive system was rejecting being fed from my stomach. I responded well to the intravenous feeding and put on more than 10 kg in weight. With treatment I became less despondent and had a more positive outlook. It took a few more weeks of treatment to get me out of bed and also to attempt walking; first with a zimmer and then with a stick. This was a slow process at first but with practice it became easier as my confidence increased. When I was discharged twelve weeks later I was able to walk reasonably confidently with the aid of a stick.

During my stay on the ward, the staff at all levels from housekeeping to the very senior consultants always gave me the impression that they were doing everything they could to effectively treat me knowing there was a very fine balancing act between treatment and the immunosuppressant anti-rejection medicine. At all times I was included in the information regarding the direction of treatment. The consultants were very thorough in researching treatments. The support, encouragement and patience I received played a large part in my recovery. I will forever be grateful to all who administered care to me and say a huge thank you.

Learning points.

Patients who are immunosuppressed can develop concurrent infections such as herpes simplex oesophagitis and chronic norovirus infection.

Presentation of patients with norovirus may be atypical with chronic diarrhoea rather than acute vomiting, abdominal pain and diarrhoea.

It is important to consider molecular testing of immunosuppressed patients for norovirus in addition to routine stool cultures.

Acknowledgments

The clinical expertise from specialists in infectious diseases, haematology, cardiology and the cardiac transplant team was immensely helpful in the investigation and treatment of this patient.

Footnotes

Contributors: GA created the first draft of the case report. AS, IA and SD reviewed and contributed to subsequent drafts and the final draft.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Wright S, Kleven D, Kapoor R, et al. . Recurring Norovirus & Sapovirus Infection in a Renal Transplant Patient. IDCases 2020;20:e00776 10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997;32:920–4. 10.3109/00365529709011203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kapikian AZ, Wyatt RG, Dolin R, et al. . Visualization by immune electron microscopy of a 27-nm particle associated with acute infectious nonbacterial gastroenteritis. J Virol 1972;10:1075–81. 10.1128/JVI.10.5.1075-1081.1972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Patel MM, Hall AJ, Vinjé J, et al. . Noroviruses: a comprehensive review. J Clin Virol 2009;44:1–8. 10.1016/j.jcv.2008.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rossignol J-F, El-Gohary YM. Nitazoxanide in the treatment of viral gastroenteritis: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;24:1423–30. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03128.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xiao S, Tang J, Li Y. Airborne or fomite transmission for norovirus? A case study revisited. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14:1571 10.3390/ijerph14121571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen M-Y, Chen W-C, Chen P-C, et al. . An outbreak of norovirus gastroenteritis associated with asymptomatic food handlers in Kinmen, Taiwan. BMC Public Health 2016;16 10.1186/s12889-016-3046-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Costantini VP, Cooper EM, Hardaker HL, et al. . Epidemiologic, virologic, and host genetic factors of norovirus outbreaks in long-term care facilities. Clin Infect Dis 2016;62:1–10. 10.1093/cid/civ747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Robilotti E, Deresinski S, Pinsky BA. Norovirus. Clin Microbiol Rev 2015;28:134–64. 10.1128/CMR.00075-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bok K, Prevots DR, Binder AM, et al. . Epidemiology of norovirus infection among immunocompromised patients at a tertiary care research Hospital, 2010–2013. Open Forum Infectious Diseases 2016;3 10.1093/ofid/ofw169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Glass RI, Parashar UD, Estes MK. Norovirus gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2009;361:1776–85. 10.1056/NEJMra0804575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Woodward J, Gkrania-Klotsas E, Kumararatne D. Chronic norovirus infection and common variable immunodeficiency. Clin Exp Immunol 2017;188:363–70. 10.1111/cei.12884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dhakal P, Gami R, Appiah A, et al. . Clinical features and outcomes of mycophenolate mofetil-induced diarrhea: a systematic review. J Adv Med Med Res 2017;24:1–9. 10.9734/JAMMR/2017/37412 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ghusson N, Vasquez G, Norovirus- ST. And sapovirus-associated diarrhea in three renal transplant patients. Case Reports in Infectious Diseases 2018;2018:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Excellence, N Ribavirin | drug | BNF content published by NICE, 2020. Available: <https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/ribavirin.html#cautions> [Accessed 17 Apr 2020].

- 16. Ruis C, Brown L-AK, Roy S, et al. . Mutagenesis in norovirus in response to Favipiravir treatment. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2173–6. 10.1056/NEJMc1806941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]