Racial and ethnic disparities in reproductive health are prevalent and can be reduced through policy-level strategies and by confronting bias and racism.

Abstract

Racial and ethnic disparities in women's health have existed for decades, despite efforts to strengthen women's reproductive health access and utilization. Recent guidance by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) underscores the often unacknowledged and unmeasured role of racial bias and systemic racial injustice in reproductive health disparities and highlights a renewed commitment to eliminating them. Reaching health equity requires an understanding of current racial–ethnic gaps in reproductive health and a concerted effort to develop and implement strategies to close gaps. We summarized national data for several reproductive health measures, such as contraceptive use, Pap tests, mammograms, maternal mortality, and unintended pregnancies, by race–ethnicity to inform health-equity strategies. Studies were retrieved by systematically searching the PubMed (2010–2020) electronic database to identify most recently published national estimates by race–ethnicity (non-Hispanic Black or African American, Hispanic or Latinx, and non-Hispanic White women). Disparities were found in each reproductive health category. We describe relevant components of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act, which can help to further strengthen reproductive health care, close gaps in services and outcomes, and decrease racial–ethnic reproductive health disparities. Owing to continued diminishment of certain components of the ACA, to optimally reach reproductive health equity, comprehensive health insurance coverage is vital. Strengthening policy-level strategies, along with ACOG's heightened commitment to eliminating racial disparities in women's health by confronting bias and racism, can strengthen actions toward reproductive health equity.

Despite significant strides in women's reproductive health, disparities in access and outcomes remain, especially for racial–ethnic minorities in the United States.1–4 Reports document decades-long racial–ethnic disparities in several areas of reproductive health, including contraceptive use, sexually transmitted infection care and human papillomavirus vaccination among younger women aged 18–25 years,5 reproductive cancers,6 preterm deliveries and low-birth-weight neonates, and maternal morbidity and mortality.7 Data suggest that the disproportionate risk for women of color for reproductive health access and outcomes expand beyond individual-level risks and include social and structural factors, such as fewer neighborhood health services, less insurance coverage, decreased access to educational and economic attainment, and even practitioner-level factors such as racial bias and stereotyping.1,4,8 The Center for Reproductive Rights describes this racial–ethnic gap as a human rights issue and suggests that, “several U.S. policies may exacerbate these disparities by disproportionately burdening access to health care for women of color.”4 Solutions that lead to increased access for women must remove these social and structural barriers so that women, especially underserved racial and ethnic minority women, may access and utilize reproductive health services as needed without clinician bias or other obstacles.9

Healthy People 2020, the science-based national guidance document, considers improved health care access by making the elimination of health disparities and improvement of health for all groups an overarching goal for the United States, including for reproductive health.10 Policy-level interventions, which are often based on political will, can help move the needle toward health equity by leveling the field and reducing how often subjective bias, including individual racial bias and structural racism, factor into health care accessibility, acceptability, decision-making, and affordability.11 The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) is an example of a social-structural-policy–level intervention that helps facilitate national prevention goals by increasing health care access for millions of previously uninsured and underinsured persons.12–14 Although legal challenges continue to threaten the potential for fully expanded reproductive health access and services for women (Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/AOG/C152), the ACA has provided large gains for women who would otherwise be without health care or have copays as an access barrier.12–14 However, because federal and state rulings continue to diminish portions of the ACA that allow access to contraceptives, optimal health parity for reproductive access and services will require a fully comprehensive national health insurance reform strategy that removes barriers and strengthens access. In some cases, even when medical insurance is available among women in the same socioeconomic strata, persistent, unexplained disparities persist and suggest that racism and other social and clinician-level issues are factors; life-course approaches to understanding women and their contexts are needed by clinicians and care systems to optimize care.

The health of persons of color in the United States has been adversely affected by centuries of social and structural factors, such as unequal access to educational and employment opportunities, lack of health care access, redlining (structural racism in the U.S. housing system that forced people of color into specific neighborhoods and has contributed to stark and persistent racial disparities in wealth and financial well-being), distrust of physicians, a segregated health care workforce, negative perceptions of the health care system, and disproportionate engagement with a legal–justice system that is rooted in racism and that disproportionately incarcerates non-Hispanic Black or African American and Hispanic or Latinx compared with non-Hispanic White (hereafter referred to as Black, Hispanic, and White) peoples.2,4,7,8,15–19 These all negatively affect reproductive health outcomes and require multipronged anti-racist approaches to tear away these centuries-old systems of racism. Women of color must be listened to with empathy and solidarity, so that care and treatment responses can be appropriate; this requires a more racially and ethnically diverse workforce, anti-racist education at every level of clinical training, and increased inclusion of doulas and other patient advocates in maternal care. Additionally, clinicians should ensure that patients are fully informed regarding treatment and care options. This requires cultural humility, mindfulness, transparency, and acknowledgement of the historical injustices that have occurred and a commitment to relegate them to history. Educational trainings of all obstetrician–gynecologists (ob-gyns) regarding these social and historical contexts are warranted to strengthen patient care. Therefore, the purpose of this commentary is to update regarding reproductive health disparities in the United States and inform national health-equity efforts.

REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH DISPARITIES, ACCESS, SERVICES, AND OUTCOMES

Nearly one in three women aged 19–64 years, approximately 27 million women, were uninsured, and another 45 million delayed or avoided health care because of cost in 2010, before the ACA was implemented nationally.20 By 2018, after implementation of the ACA, an estimated 10.8 million women were uninsured, a decrease compared with 2010.21 However, gains have stalled in recent years. Having health insurance improves the chances that women will have a regular source of care and access.22–25 By including a package of women's preventive services as recommended by the Department of Health and Human Services,14 access through the ACA includes Pap tests, mammograms, and some contraceptives without copays for women; this improves comprehensive care and access for all women and may ultimately help reduce reproductive health disparities. A recent review confirmed that, since implemented in 2010, the ACA has resulted in improvements in overall coverage, access to health care, affordability, preventive care use, mental health care, use of contraceptives, and perinatal outcomes for women.23–25 However, huge challenges to coverage, access, and affordability remain for women throughout the country, and particularly in 14 mostly southern states that have not expanded Medicaid eligibility and continue to lack access through the ACA.26–28 This coverage gap disproportionately affects disenfranchised populations in the southern states and likely contributes to the wide racial–ethnic health disparities in health access and several health outcomes for women.27,28

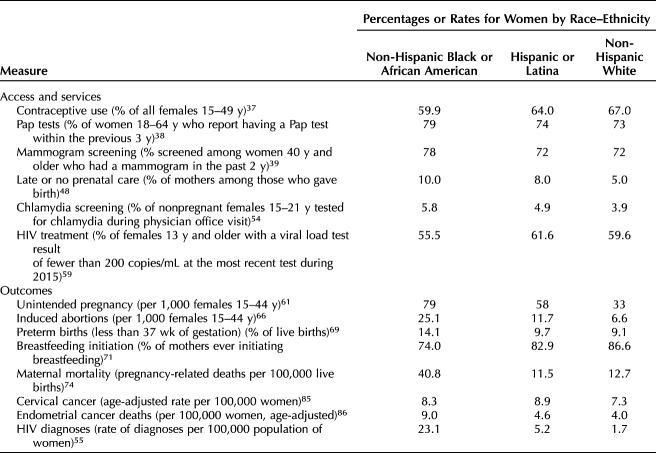

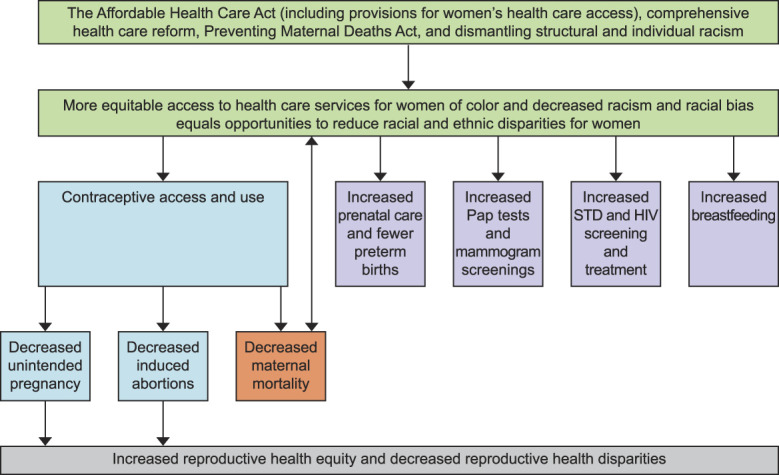

For this commentary, we reviewed and summarized (Table 1) recent national estimates for several reproductive health measures using a PubMed review (2010–2020), including services (contraceptive use,29–37 Pap tests,38–40 mammogram screening,39–45 late or no prenatal care,46–48 chlamydia screening,49–54 human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] treatment55–60) and outcomes (unintended pregnancy,61–63 induced abortions,64–66 preterm births,67–69 breastfeeding initiation,10,70–73 maternal mortality,15,74–82 cervical cancer,83–85 endometrial cancer deaths,86,87 HIV diagnoses88,89) by race–ethnicity (Black, Hispanic, and White, as classified by the authors of the studies, and examined, because we are exploring racial–ethnic disparities). By highlighting the current racial–ethnic disparities in reproductive health, our goal was to show that there are opportunities to strengthen access and care for women, toward improved reproductive health equity (Fig. 1), as underscored recently with a renewed commitment from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to eliminate these disparities.8 For the three topics below (contraceptive access, maternal mortality, and HIV diagnoses), we considered focused strategies using multilevel approaches, including addressing racism, which may work synergistically to improve clinician awareness, and access and outcomes for women. If time reveals improved access and outcomes for women of color for the three issues discussed below, lessons learned could inform other reproductive health disparity issues summarized in Table 1 and ultimately lead us toward reduced reproductive health disparities.

Table 1.

Estimated Rates of Selected Reproductive Health Measures by Race–Ethnicity, 2020

Fig. 1. Conceptual model of expanded health care access, including reduced health care professional bias, and potential effect on racial and ethnic reproductive health disparities. STD, sexually transmitted disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Sutton. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Reproductive Health. Obstet Gynecol 2021.

Focused Strategies

Contraceptive Access and Use

Cost is a known barrier to contraceptive access and use for some women.29,30 High contraceptive costs affects consistent use, which subsequently affects risk to reproductive autonomy31 and rates of unplanned pregnancies. Highly effective long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods, such as the intrauterine device and dermal implants, have higher upfront costs.29,30,32 Providing contraceptive access by removing cost barriers can be a highly effective means of increasing reproductive autonomy for all women regardless of race–ethnicity and social status.33,34 Pharmacy-level barriers also exist and can lead to some women not obtaining even prescribed or over-the-counter hormonal contraceptives. Increased reproductive access–focused training for pharmacists is important as part of expanded access for women.35

Having health insurance is associated with an increase in the likelihood of receiving family planning services,36 which can strengthen reproductive autonomy31 and decrease unplanned pregnancies. Contraceptive use among females aged 15–49 years is statistically more common among White females (67%) compared with Black females (59.9%).37 Strengthening access to comprehensive health insurance can help close this gap in contraceptive access and use (Fig. 1), as evidenced by data from a state with expanded Medicaid access.90

When considering LARC and permanent sterilization, clinicians must be aware of the historical legacy of abuse and eugenics in which women of color have been disproportionately sterilized without their consent (compared with White women) as a result of explicit bigotry. Data suggest that women of color are offered LARC more often sometimes owing to implicit biases.91 Awareness of historical and modern-day racial injustices often contribute to the lower rate of contraceptive use among Black and Hispanic women; there is a distrust by some patients that has yet to be acknowledged by many clinicians.92 To combat this, patient-centered shared decision making is a vital component of all contraceptive counseling.93

Laws that have restricted women's access to family planning and reproductive health services have also contributed to rising maternal mortality rates.81 Policy-level interventions are warranted to save women's lives. Especially with as many as 50% of pregnancies in the United States being unintended, preventing unintended pregnancies will help prevent maternal deaths. The Preventing Maternal Deaths Act, signed into law in 2018, supports state maternal mortality review committees to review every pregnancy-related death and, based on their findings, develop recommendations for how to prevent future maternal deaths; this will allow care gaps can be identified and closed.15,82 (Fig. 1).

Maternal Mortality

Maternal mortality disparities have been documented for decades in the United States.74 These disparities are a public health failure that have recently generated increased attention and policy shifts, especially because approximately 60% of pregnancy-related deaths are preventable.74 Persistently, women of color have been disproportionately affected by maternal mortality; Black women and American Indian or Alaska Native women are 3.3 and 2.5 times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than White women, respectively.74 When individual recent cases were reviewed, clinician-level biases and racism often contributed to delayed or absent care that led to deaths.75–79 Establishment of management protocols by hospitals and medical practices for the management of conditions such as postpartum hemorrhage,80 hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, and maternal cardiovascular disease will lessen the disparate care provided to women of color, increase standardized care, and improve maternal morbidity and mortality. Such protocols are necessary in both the inpatient and outpatient arenas, at the hospital or health care system level, as well as in independent medical practices.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus Diagnoses

In women, those who are Black and Hispanic account for 75% of new diagnoses of HIV.55 Given that 85.2% of women diagnosed with HIV acquire it through heterosexual contact, comprehensive and accessible gynecologic care, including HIV and sexually transmitted infection prevention and treatment programs, are essential to decrease the rates of HIV infection.55–60 Barriers to accessing such care by Black and Hispanic women need to be eliminated by providing high-quality, culturally sensitive, accessible care in local communities.

Multiple approaches are needed to address these alarming HIV diagnosis disparities, including addressing disproportionate poverty through microfinance interventions, ensuring equitable access to educational and career opportunities and reproductive health care access, and increasing access to biomedical prevention interventions, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis.88,89 Data show that Black women are less likely to be prescribed pre-exposure prophylaxis, a known, evidence-based approach to HIV prevention, compared with White women and men.94 Increasing pre-exposure prophylaxis bias-awareness is one additional strategy to increase pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake among at-risk Black women who are HIV-negative.95 Improving linkage and retention in HIV care for Black women who are HIV-positive are also important strategies to address HIV disparities. Educational strategies regarding HIV-prevention tools with clinicians and also with all sexually active women are warranted.91 Although HIV screening for sexually active women during gynecology visits is supported without copays, fewer than 20% of sexually active women reported receiving an HIV test during the past year in a recent report.96 Offering routine HIV screenings should be fully incorporated during obstetrics and gynecology visits; early diagnosis is vital for timely treatment and decreased morbidity and mortality (Fig. 1).

CONCLUSION

Racial–ethnic disparities in reproductive health access, services, and outcomes are prevalent and require heightened awareness and strategies to close these long-standing disparity gaps. Specifically for contraceptive access, preventing maternal deaths, and decreasing HIV infections, developing and strengthening policies and laws that include a focus on dismantling structural racism and implicit bias are crucial as part of the solution. Because race and ethnicity are social constructs, dismantling the structures developed based on race–ethnicity will require social solutions.97 Upstream federal-level solutions for structural racism will require the Departments of Justice, Education, Labor, and Housing and Urban Development to dismantle current systems that are rooted in a legacy of unequal treatment and move toward anti-racist judicial, educational, income (especially with hourly, low-wage jobs, which disproportionately decrease flexibility and access for women, especially women of color), and housing solutions; legislative advocacy by local and national clinicians will be vital to these efforts.98–102 Commitment from downstream leadership, followed by implementing policy-level platforms, will help strengthen the ability of ob-gyns and other clinicians to provide necessary services, improve outcomes for women, and reduce racial–ethnic reproductive health disparities.

In addition, these persistent disparities will require multiple levels of partnerships and collaborations to improve outcomes for women of color. For communities, including schools and community-based service organizations, increasing awareness and empowering women through peer education and media campaigns that are transparent regarding historical injustices while also informing regarding evidence-based services, are vital. Some community-based approaches have successfully engaged low-income Hispanic and Black women in accessing cervical and breast cancer screening services.103–106 Health care and professional organizations should hold clinicians and hospitals accountable by encouraging standardized, patient-informed approaches for clinical care and developing strategies to measure and reduce racial–ethnic disparities by linking services provided to measurable health outcomes and performance standards. At the systems level, this can help reduce reproductive health disparities by providing incentives107 for identifying and removing clinician barriers, with the goal of improved access and outcomes for patients.

Finally, as ob-gyns, we must continue to hold ourselves accountable for the improved health of our patients by addressing the racism and biases that contribute to reproductive health disparities. With renewed commitment and action from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists,108 we can help facilitate the dismantling of systemic racism that contributes to reproductive health disparities by helping to strengthen the current national health plan for women's health provisions or advocating for a more comprehensive universal health care system or both, increasing the diversification of our workforce, training our residents and fellows to understand the role of racism as it affects patients' care and how to address it, understanding our own biases, and advocating for our patients to help them feel safer in their communities that may be unjustly affected by structural racism and health inequities.9 By doing so, we will greatly improve reproductive health equity and decrease the excess burden for Black, Hispanic, and Native American women in the United States.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal's requirements for authorship.

Peer reviews and author correspondence are available at http://links.lww.com/AOG/C153.

REFERENCES

- 1.Racial and ethnic disparities in obstetrics and gynecology. Committee Opinion No. 649. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:e130–4. doi: 10.1097/AOG.000000000000121326595584 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anachebe NF, Sutton MY. Racial disparities in reproductive health outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;188:S37–42. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boonstra HD. The impact of government programs on reproductive health disparities. Guttmacher Pol Rev 2008;11:6–12. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Center for Reproductive Rights. Addressing disparities in reproductive and sexual health care in the U.S. Accessed October 14, 2020. http://reproductiverights.org/en/node/861

- 5.Murray Horwitz ME, Pace LE, Ross-Degnan D. Trends and disparities in sexual and reproductive health behaviors and service use among young adult women (aged 18–25 years) in the United States, 2002–2015. Am J Pub Health 2018;108:S336–43. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu L, Sabatino SA, White MC. Rural–urban and racial/ethnic disparities in invasive cervical cancer incidence in the United States, 2010–2014. Prev Chronic Dis 2019;16:180447. doi: 10.5888/pcd16.180447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Creanga AA, Bateman BT, Kuklina EV, Callaghan WM. Racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity: a multistate analysis, 2008-2010. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;210:435–8. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.11.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Racial bias: statement of policy. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.acog.org/clinical-information/policy-and-position-statements/statements-of-policy/2017/racial-bias

- 9.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Our commitment to changing the culture of medicine and eliminating racial disparities in women's health outcomes. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.acog.org/about/our-commitment-to-changing-the-culture-of-medicine-and-eliminating-racial-disparities-in-womens-health-outcomes

- 10.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/leading-health-indicators/2020-LHI-Topics

- 11.Hostetter M, Klein S. In focus: reducing racial disparities in health care by confronting racism. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletter-article/2018/sep/focus-reducing-racial-disparities-health-care-confronting

- 12.Sonfield A, Pollack HA. The Affordable Care Act and reproductive health: potential gains and serious challenges. J Health Polit Pol L 2013;38:373–91. doi: 10.1215/03616878-1966342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office on Women's Health. Affordable Care Act improves women's health. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.womenshealth.gov/30-achievements/31

- 14.Health Resources & Services Administration. Women's preventive services guidelines. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.hrsa.gov/womens-guidelines-2019

- 15.Kozhimannil KB, Hernandez E, Mendez DD, Chapple-McGruder T. Beyond the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act: implementation and further policy change. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190130.914004/full/

- 16.Krieger N, Van Wye G, Huynh M, Waterman PD, Maduro G, Li W, et al. Structural racism, historical redlining, and risk of preterm birth in New York City, 2013–2017. Am J Public Health 2020;110:1046–53. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2020.305656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prather C, Fuller TR, Marshall KJ, Jeffries WL., IV The impact of racism on the sexual and reproductive health of African American women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2016;25:664–71. doi:10.1089/jwh.2015.5637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans MK, Rosenbaum L, Malina D, Morrissey S, Rubin EJ. Diagnosing and treating systemic racism. N Engl J Med 2020;383:274–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2021693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardeman RR, Medina EM, Boyd RW. Stolen breaths. N Engl J Med 2020;383:197–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2021072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robertson R, Collins SR. Women at risk: why increasing numbers of women are failing to get health care they need and how the Affordable Care Act will help. Findings from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey of 2010. Issue Brief 2011;3:1–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaiser Family Foundation. Women's health insurance coverage. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/womens-health-insurance-coverage-fact-sheet/

- 22.Lillie-Blanton M, Hoffman K. The role of health insurance coverage in reducing racial/ethnic disparities in health care. Health Aff 2005;24:398–408. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benefits to women of Medicaid expansion through the Affordable Care Act. Committee Opinion No. 552. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121:223–5. doi: 10.1097/01.aog.0000425664.05729.2c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee LK, Chien A, Stewart A, Truschel L, Hoffmann J, Portillo E, et al. Women's coverage, utilization, affordability, and health after the ACA: a review of the literature. Health Aff (Millwood) 2020; 39:387–94. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koh HK, Graham G, Glied SA. Reducing racial and ethnic disparities: the action plan from the Department of Health and Human Services. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:1822–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sommers BD, Baicker K, Epstein AM. Mortality and access to care among adults after state Medicaid expansions. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1025–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1202099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garfield R, Orgera K, Damico A. The coverage gap: uninsured poor adults in states that do not expand Medicaid. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid/

- 28.Artiga S, Damico A, Garfield R. The impact of the coverage gap for adults in states not expanding Medicaid by race and ethnicity. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/the-impact-of-the-coverage-gap-in-states-not-expanding-medicaid-by-race-and-ethnicity/

- 29.Kavanaugh ML, Jones RK, Finer LB. Perceived and insurance-related barriers to the provision of contraceptive services in U.S. abortion care settings. Women Health Issues 2011;21:S26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gariepy AM, Simon EJ, Patel DA, Creinin MD, Schwarz EB. The impact of out-of-pocket expense on IUD utilization among women with private insurance. Contraception 2011;84:e39–42. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Potter JE, Stevenson AJ, Coleman-Minahan K, Hopkins K, White K, Baum SE, et al. Challenging unintended pregnancy as an indicator of reproductive autonomy. Contraception 2019;100:1–4. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2019.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dehlendorf C, Park SY, Emeremni CA, Comer D, Vincett K, Borrero S. Racial/ethnic disparities in contraceptive use: variation by age and women's reproductive experiences. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.01.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Birgisson NE, Zhao Q, Secura GM, Madden T, Peipert JF. Preventing unintended pregnancy: the contraceptive CHOICE project in review. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2015;24:349–53. doi:10.1089/jwh.2015.5191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Secura GM, Madden T, McNicholas C, Mullersman J, Buckel CM, Zhao Q, et al. Provision of no-cost, long-acting contraception and teenage pregnancy [published erratum appears in N Engl J Med 2014;372:297]. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1316–23. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1400506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cappiello JD, Schommer LM. Increasing access to care through pharmacy provision of hormonal contraceptives: a nursing perspective. Womens Healthc A Clin J NPs 2019. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.npwomenshealthcare.com/increasing-access-to-care-through-pharmacy-provision-of-hormonal-contraceptives-a-nursing-perspective/ [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saleeby E, Brindis CD. Women, reproductive health, and health reform. JAMA 2011;306:1256–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daniels K, Abma JC. Current contraceptive status among women aged 15–49: United States, 2015–2017. NCHS Data Brief, No. 327. National Center for Health Statistics; 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaiser Family Foundation. Women ages 18-64 who report having a Pap smear within the past three years by race/ethnicity. Timeframe: 2016-2018. Accessed September 8, 2020. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/percent-of-women-ages-18-64-who-report-having-had-a-pap-smear-within-the-past-three-years-by-raceethnicity/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

- 39.Kaiser Family Foundation. Women age 40 and older who report having had a mammogram within the past two years by race/ethnicity. Timeframe: 2016-2018. Accessed September 8, 2020. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/state-indicator/mammogram-rate-for-women-40-years/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

- 40.Swan J, Breen N, Coates RJ, Rimer BK, Lee NC. Progress in cancer screening practices in the United States. Results from the 2000 national health interview survey. Cancer 2003;97:1528–40. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sabatino SA, Coates RJ, Uhler RJ, Breen N, Tangka F, Shaw KM. Disparities in mammography use among US women aged 40-64 years, by race, ethnicity, income, and health insurance status, 1993-2005. Med Care 2008;46:692–700. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817893b1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Njai R, Siegel PZ, Miller JW, Liao Y. Misclassification of survey responses and Black-White disparity in mammography use, behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 1995-2006. Prev Chronic Dis 2011;8:A59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levy AR, Bruen BK, Ku L. Health care reform and women's insurance coverage for breast and cervical cancer screening. Prev Chronic Dis 2012;9:120069. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.120069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DeGroff A, Carter A, Kenney K, Myles Z, Melillo S, Royalty J, et al. Using evidence-based interventions to improve cancer screening in the national breast and cervical cancer early detection program. J Public Health Manag Pract 2016;22:442–9. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adams EK, Breen N, Joski PJ. Impact of the national breast and cervical cancer early detection program on mammography and Pap test utilization among White, Hispanic, and African American women. Cancer 2007;109(2 suppl):348–58. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ranji U, Salganicoff A. Medicaid and women's health coverage two years into the Affordable Care Act. Womens Health Issues 2015;25:604–7. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2015.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cox RG, Zhang L, Zotti ME, Graham J. Prenatal care utilization in Mississippi: racial disparities and implications for unfavorable birth outcomes. Matern Child Health J 2011;15:931–42. 10.1007/s10995-009-0542-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Child Trends Data Bank. Late or no prenatal care. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.childtrends.org/indicators/late-or-no-prenatal-care

- 49.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2018. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/STDSurveillance2018-full-report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chesson HW, Kent CK, Owusu-Edusel K, Jr, Leichliter JS, Aral SO. Disparities in sexually transmitted disease rates across the eight Americas. Sex Transm Dis 2012;39:458–64. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318248e3eb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harling G, Subramanian S, Barnighausen T, Kawachi I. Socioeconomic disparities in sexually transmitted infections among young adults in the United States: examining the interaction between income and race/ethnicity. Sex Transm Dis 2013;40:575–81. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31829529cf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep 2015;64:1–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wiehe SE, Rosenman MB, Wang J, Katz BP, Fortenberry JD. Chlamydia screening among young women: individual- and provider-level differences in testing. Pediatrics 2011;127:e336–44. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-0967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoover KW, Leichliter JS, Torrone EA. Chlamydia screening among females aged 15–21 years—multiple data sources, United States, 1999–2010. MMWR Suppl 2014;63(suppl-2):80–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report, 2018 (preliminary); vol. 30. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2018-preliminary-vol-30.pdf

- 56.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents, Department of Health and Human Services. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents living with HIV. Accessed December 3, 2020. http://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/guidelines/documents/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf

- 58.Health Resources & Services Administration. Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program. Data reports and slide decks. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://hab.hrsa.gov/data/data-reports

- 59.Hoover KW, Hu X, Porter SE, Buchacz K, Bond MD, Siddiqi AE, et al. HIV diagnoses and the HIV care continuum among women and girls aged ≥13 years-39 states and the District of Columbia, 2015-2016. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2019;81:251–6. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Geter A, Sutton MY, Armon C, Buchacz K, HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. Disparities in viral suppression and medication adherence among women in the USA, 2011-2016. AIDS Behav 2019;23:3015–23. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02494-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008-2011. N Engl J Med 2016;374:843–52. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1506575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Shifts in intended and unintended pregnancies in the United States, 2001-2008. Am J Public Health 2014;104(suppl 1):S43–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thomas A. Policy solutions for preventing unplanned pregnancy. Accessed October 15, 2020. http://www.brookings.edu/reports/2012/03_unplanned_pregnancy_thomas.aspx

- 64.Jones RK, Kavanaugh ML. Changes in abortion rates between 2000 and 2008 and lifetime incidence of abortion. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117:1358–66. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821c405e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dehlendorf C, Harris LH, Weitz TA. Disparities in abortion rates: a public health approach. Am J Pub Health 2013;103:1772–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jatlaoui TC, Eckhaus L, Mandel MG, Nguyen A, Oduyebo T, Petersen E, et al. Abortion surveillance—United States, 2016. MMWR Surveill Summ 2019;68:1–41. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6811a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Braveman PA, Heck K, Egeret S, Marchi KS, Dominguez TP, Cubbin C, et al. The role of socioeconomic factors in Black–White disparities in preterm birth. Am J Public Health 2015;105:694–702. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Howell EA, Janevic T, Hebert PL. Differences in morbidity and mortality rates in Black, White, and Hispanic very preterm infants among New York City hospitals. JAMA Pediatr 2018;172:269–77. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.4402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MJK, Rossen LM. Births: provisional data for 2018. Vital statistics rapid release; No. 7. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr-007-508.pdf?utm_source=morning_brew [Google Scholar]

- 70.Beauregard JL, Hamner HC, Chen J, Avila-Rodriguez W, Elam-Evans LD, Perrine CG. Racial disparities in breastfeeding initiation and duration among U.S. infants born in 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:745–8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6834a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rates of any and exclusive breastfeeding by socio-demographics among children born in 2016, CDC National Immunization Survey. Accessed December 3, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/nis_data/rates-any-exclusive-bf-socio-dem-2016.htm

- 72.Kozhimannil KB, Jou J, Gjerdingen DK, McGovern PM. Access to workplace accommodations to support breastfeeding after passage of the Affordable Care Act. Womens Health Issues 2016;26:6–13. 10.1016/j.whi.2015.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Feldman-Winter L Ustianov J Butts-Dion S Heinrich P Merewood A, et al. Best fed beginnings: a nationwide quality improvement initiative to increase breastfeeding. Pediatrics 2017;140:e20163121. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Petersen EE, Davis NL, Goodman D, Cox S, Syverson C, Seed K, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in pregnancy-related deaths—United States, 2007–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:762–5. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6835a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Callaghan WM. Maternal mortality: addressing disparities and measuring what we value. Obstet Gynecol 2020;135:274–5. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Young S. Confronting racial bias in maternal deaths. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.webmd.com/baby/news/20200117/confronting-racial-bias-in-maternal-deaths

- 77.Howell EA. Reducing disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2018;61:387–99. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Underwood L. Saving moms, saving lives. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200423.488851/full/

- 79.Chuck E, Assefa H. She hoped to shine a light on maternal mortality among Native Americans. Instead, she became a statistic of it. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/she-hoped-shine-light-maternal-mortality-among-native-americans-instead-n1131951

- 80.Main EK, Chang SC, Dhurjati R, Cape V, Profit J, Gould JB. Reduction in racial disparities in severe maternal morbidity from hemorrhage in a large-scale quality improvement collaborative. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020;223:123.e1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.01.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Taylor J, Novoa C, Hamm K, Phadke S. Eliminating racial disparities in maternal and infant mortality: a comprehensive policy blueprint. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2019/05/02/469186/eliminating-racial-disparities-maternal-infant-mortality/ [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hawkins SS, Ghiani M, Harper S, Baum CF, Kaufman JS. Impact of state-level changes on maternal mortality: a population-based, quasi-experimental study. Am J Prev Med 2020;58:165–74. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yoo W, Kim S, Huh WK, Dilley S, Coughlin SS, Partridge EE, et al. Recent trends in racial and regional disparities in cervical cancer incidence and mortality in United States. PLoS One 2017;12:e0172548. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Benard VB, Thomas CC, King J, Massetti GM, Doria-Rose VP, Saraiya M. Vital signs: cervical cancer incidence, mortality, and screening - United States, 2007-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014;63:1004–9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. U.S. Cancer Statistics Data Visualizations Tool, based on 2019 submission data (1999-2017): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute. Accessed December 3, 2020. www.cdc.gov/cancer/dataviz. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Henley SJ, Miller JW, Dowling NF, Benard VB, Richardson LC. Uterine cancer incidence and mortality—United States, 1999–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:1333–8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6748a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Doll KM, Winn AN, Goff BA. Untangling the Black-White mortality gap in endometrial cancer: a cohort simulation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;216:324–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bradley EL, Williams AM, Green S, Lima AC, Geter A, Chesson HW, et al. Disparities in incidence of human immunodeficiency virus infection among Black and White women—United States, 2010–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:416–18. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6818a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bradley ELP, Geter A, Lima AC, Sutton MY, Hubbard McCree D. Effectively addressing human immunodeficiency virus disparities affecting US Black women. Health Equity 2018;2:329–33. doi: 10.1089/heq.2018.0038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Moniz MH, Kirch MA, Solway E, Goold SD, Ayanian JZ, Kieffer EC, et al. Association of access to family planning services with Medicaid expansion among female enrollees in Michigan. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e181627. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.1627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kathawa CA, Arora KS. Implicit bias in counseling for permanent contraception: historical context and recommendations for counseling. Health Equity 2020;4:326–9. doi: 10.1089/heq.2020.0025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Higgins JA, Kramer RD, Ryder KM. Provider bias in long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) promotion and removal: perceptions of young adult women. Am J Public Health 2016;106:1932–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Holt K, Reed R, Crear-Perry J, Scott C, Wolf S, Dehlendorf C. Beyond same-day long-acting reversible contraceptive access: a person-centered framework for advancing high-quality, equitable contraceptive care. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020;222:S878.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.11.1279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Huang YA, Zhu W, Smith DK, Harris N, Hoover KW. HIV preexposure prophylaxis, by race and ethnicity — United States, 2014–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:1147–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bradley ELP, Hoover KW. Improving HIV preexposure prophylaxis implementation for women: summary of key findings from a discussion series with women's HIV prevention experts. Women Health Issues 2018;29:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2018.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Evans ME, Tao G, Porter SE, Gray SC, Huang YA, Hoover KW. Low HIV testing rates among US women who report anal sex and other HIV sexual risk behaviors, 2011-2015. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;219:383–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.08.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yudell M, Roberts D, DeSalle R, Tishkoff S. Taking race out of human genetics. Science 2016;351:564–5. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Balko R. There's overwhelming evidence that the criminal justice system is racist. Here's the proof. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/opinions/systemic-racism-police-evidence-criminal-justice-system/ [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chatterji R. Fighting systemic racism in K-12 education: helping allies move from the keyboard to the school board. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education-k-12/news/2020/07/08/487386/fighting-systemic-racism-k-12-education-helping-allies-move-keyboard-school-board/ [Google Scholar]

- 100.Feagin JR. Excluding Blacks and others from housing: the foundation of White racism. Cityscape A J Pol Dev Res 1999;4:79–91. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Greene S, Galvez MM, Ramakrishnan K, Brown M. HUD ignores evidence on discrimination, segregation and concentrated poverty in fair housing proposal. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/101823/hud_ignores_evidence_on_discrimination_segregation_and_concentrated20poverty_in_fair_housing_proposal_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 102.Patrick K, Berlan M, Harwood M. Low-wage jobs held primarily by women will grow the most over the next decade. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://nwlc-ciw49tixgw5lbab.stackpathdns.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Low-Wage-Jobs-Held-Primarily-by-Women-Will-Grow-the-Most-Over-the-Next-Decade-2018.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 103.Glynn SJ. An unequal division of labor: how equitable workplace policies would benefit working mothers. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2018/05/18/450972/unequal-division-labor/ [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fouad MN, Partridge E, Dignan M, Holt C, Johnson R, Nagy C, et al. A community-driven action plan to eliminate breast and cervical cancer disparity: successes and limitations. J Cancer Educ 2006;21(1 suppl):S91–100. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2101s_16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bullock K, McGraw SA. A community capacity-enhancement approach to breast and cancer screening among older women of color. Health Soc Work 2006;31:16–25. doi: 10.1093/hsw/31.1.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rosenbaum S, Wood SF. Turning back the clock on women's health in medically underserved communities. Women Health Issues 2015;25:601–3. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2015.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chin MH. Creating the business case for achieving health equity. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:792–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3604-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Joint statement: collective action addressing racism. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.acog.org/news/news-articles/2020/08/joint-statement-obstetrics-and-gynecology-collective-action-addressing-racism [Google Scholar]