Clinical Implications.

-

•

Health information should build trust, promote health protection actions, and ensure adherence to recommended health measures. Despite the context of a coronavirus pandemic that has potential to trigger acute asthma attacks, only a minority of sources provided explicit self-management information.

Asthma affects more than 339 million people worldwide1 and, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), those with severe asthma may be at high risk of becoming severely ill with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).2 In addition to following COVID-19 prevention information, people with asthma need to be supported to self-manage their condition, such as having an asthma action plan and ensuring adherence to medication. Supporting asthma self-management reduces hospitalizations, emergency department attendances, and unscheduled consultations,3 which is important when health care services are stretched.4 We aimed to rapidly review online COVID-19 information publicly available in English for people with asthma, to explore whether the information addresses relevant health actions to minimize the risk of contracting and spreading COVID-19, and encourages asthma self-management.

We searched for online COVID-19 information for people with asthma using Google search terms, for example, “asthma patient support” and “government health information.” Organizations were identified at a global level, and for 5 majority English-speaking countries (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States). The inclusion and exclusion criteria are outlined in Table I . Webpages that met the inclusion criteria were downloaded on April 20, 2020, and on May 18, 2020, to assess information changes over time. We developed a coding framework informed by the WHO guideline for emergency risk communication (ERC)5 and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) asthma guidelines.6 Relevant WHO ERC guidance components included building trust (eg, timeliness, acknowledging uncertainty, and providing links to other services), providing nontechnical and consistent messaging, and promoting health protection actions. Self-management elements of the NICE asthma guidelines, for example, adherence to preventer medication, having an asthma action plan, and speaking to a health care professional, were included. Data were extracted, and text (excluding images and videos) was coded by the authors (A.H.Y.C., B.D., T.J., or K.M.). Readability was assessed using the Flesch-Kincaid and the Simple Measure of Gobbledygook grade formulas. Intercoder reliability was assessed at random with approximately 15% of the included webpages.

Table I.

COVID-19 information for people with asthma inclusion/exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Freely and currently available online COVID-19 information | COVID-19 information that is not freely available online (therefore difficult for the public to access) or not currently available (eg, archived information) |

| Information aimed at people categorized as high-risk/vulnerable, or those with respiratory conditions, eg, asthma, or those with generic long-term conditions | Information aimed at the general population who are not at high risk (eg, information about COVID-19 for the general public), or information aimed at health care professionals |

| Information from organizations within the 5 majority native English-speaking countries (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States), or global-level information (eg, WHO) | Country-specific information that is not from 1 of the 5 included countries (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States), and information that is not for a global audience |

| Information from health information providers, global intergovernmental organizations, national governments, public health organizations, patient support organizations, and private health information services | Information from online health providers, eg, online pharmacies, medical practices, and information from other sources not listed in the inclusion criteria (eg, social media, forums, blogs, and news websites) |

| Information within countries should be at a government level and not at a state level | State-level information |

| Information available in the English language | Non-English information, even if an English translated version exists |

COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; WHO, World Health Organization.

We identified and included 102 webpages from 43 unique organizations that provided COVID-19 information for those categorized as high risk across the 6 countries/areas (data files are available from Edinburgh DataShare: https://doi.org/10.7488/ds/2982). Organizations included intergovernmental/global organizations (n = 6), government organizations (n = 8), patient support organization/charities (n = 16), private health information organizations (n = 6), and public health organizations (n = 7). Terms used to define risk groups varied across and within organizations and ranged from specific terms, for example, asthma to severe asthma, or broader terms, for example, lung or respiratory conditions. Some organizations used multiple categories to describe those at risk.

All but 1 of the organizations provided information relevant to the WHO ERC guideline. Most organizations (n = 35 [81%]) provided links to other services or information. In terms of timeliness, only 14 (33%) organizations reported reviewing or updating information within the week before the initial download date (April 20, 2020). By the second download date (May 18, 2020), three-quarters (n = 32 [74%]) stated they had reviewed or updated their information. Half the organizations (n = 23 [53%]) acknowledged or communicated uncertainty in their information, for example, “We are learning more about COVID-19 every day; CDC will update the advice below as new information becomes available.” Most (n = 32 [74%]) organizations provided consistent messaging, for example, by linking to other information organizations or providing figures and statistics from reputable organizations (eg, WHO). The mean Flesch-Kincaid readability across all organizations was 10.4 (range, 4.7-15.5), and the mean Simple Measure of Gobbledygook score was 9.9 (range, 5.5-15.8), both equating to approximately a US grade level 10 (15-16 years). Only 9 (21%) organizations provided information written at or below the average US grade level of 8 (13-14 years). Organizations provided the following precautions that people could take to protect their health during the pandemic: 37 of the 43 (86%) provided COVID-19–specific advice, for example, handwashing and isolating with symptoms, whereas 19 (44%) organizations provided information on optimizing general physical health, for example, guidance on exercise or diet, and 16 (37%) provided information about mental health and well-being.

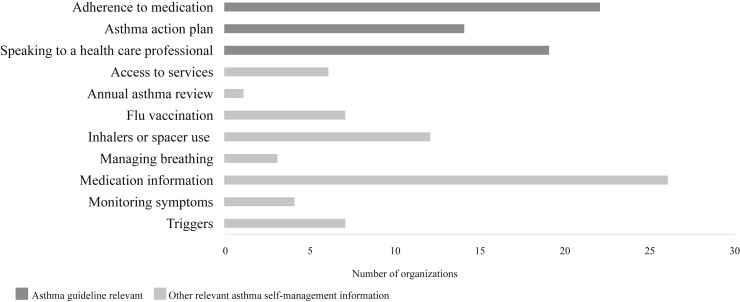

All but 7 organizations provided information about asthma self-management (n = 36 [84%]) (Figure 1 ). Just over half (n = 24 [56%]) covered information related to NICE guideline recommendations, with most highlighting adherence to medication (n = 22 [51%]) and speaking to a health care professional (n = 21 [49%]). Only 14 (33%) organizations advised following an asthma action plan, or discussed the (initially debated) role of steroids in the context of COVID-19. Of the 19 organizations that were focused on respiratory conditions or allergies, 5 (26%) did not provide asthma guideline relevant self-management information alongside their COVID-19 information. Most organizations (n = 34 [79%]) provided other asthma self-management information, for example, information about medications (n = 26), inhalers or spacer use (n = 12), triggers (n = 7), flu vaccination (n = 7), access to services (n = 6), monitoring peak flow (n = 4), breathing control (n = 3), and annual asthma reviews (n = 1).

Figure 1.

Provision of asthma self-management information by self-management information type. The graph illustrates the number of organizations that provide information in the different asthma self-management categories. The dark lines are information related to asthma guidelines; the pale gray lines are other self-management information for people with asthma.

To summarize, our rapid review found that almost all the information organizations provided information relevant to the WHO ERC guideline, with approximately half the organizations providing guideline-recommended self-management information. However, less than a third referenced following an asthma action plan—an important omission from information that is intended to help people manage potential deteriorations in asthma control. Second waves of COVID-19 are already being reported,7 , 8 highlighting the need to ensure optimal asthma management to reduce unscheduled care.3 We found important variations in the definitions of risk, which could lead to confusion especially in countries with multiple sources of information; we thus recommend that risk categories should be agreed and clarified. Future COVID-19 information should also be written to lower readability scores to increase information accessibility.

Limitations include exclusion of social media posts in the review. However, health information websites are more trusted than social media9; therefore, its exclusion may not limit findings. Although we used the WHO ERC guideline to assess the information content, we also used the NICE guidelines, which may have been less relevant to risk communication because the guidelines focus on asthma management rather than pandemic risk communication.

In conclusion, COVID-19 online information developed for people categorized as high risk of severe illness from COVID-19 largely followed the WHO ERC guideline and provided some asthma self-management strategies, though omitted advice to use (or arrange to be provided with) an asthma action plan. Although rates of provision of asthma action plans are suboptimal, in the context of a pandemic, having explicit asthma self-management information, when providing COVID-19 information for individuals with asthma, is particularly important to ensure asthma outcomes are optimized.

Acknowledgments

We thank Atena Barat, PhD, Vicky Hammersley, PhD, and Momoko Phelan for their contribution to this work.

Footnotes

No funding was received for this work.

Conflicts of interest: K. McClatchey and B. Delaney are supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) IMP2ART (IMProving IMPlementation of Asthma self-management as RouTine) programme of work (grant no. RP-PG-1016-20008), outside the current work. T. Jackson is supported by Asthma UK as part of the Asthma UK Centre for Applied Research (grant nos. AUK-AC-2012-01 and AUK-AC-2018-01), outside the current work. A. H. Y. Chan reports grants from Innovate UK, A+ Charitable Trust (Auckland District Health Board), Maurice and Phyllis Paykel Trust, Universitas 21, New Zealand Pharmacy Education Research Fund, Auckland Academic Health Alliance, Asthma UK, and the University of Auckland; reports consultancy fees from Janssen-Cilag and UCL-Business spin-out company Spoonful of Sugar Ltd; and is the recipient of the Robert Irwin Postdoctoral Fellowship, outside the submitted work. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Global Asthma Network. The Global Asthma Report 2018. Auckland, New Zealand: Global Asthma Network; 2018. Available from: http://www.globalasthmareport.org/Global%20Asthma%20Report%202018.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2020.

- 2.World Health Organization Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public: Mythbusters. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public/myth-busters Available from:

- 3.Pinnock H., Parke H.L., Panagioti M., Daines L., Pearce G., Epiphaniou E., et al. Systematic meta-review of supported self-management for asthma: a healthcare perspective. BMC Med. 2017;15:64. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0823-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willan J., King A.J., Jeffery K., Bienz N. Challenges for NHS hospitals during covid-19 epidemic. BMJ. 2020;368:m1117. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2017. Communicating risk in public health emergencies: a WHO guideline for emergency risk communication (ERC) policy and practice. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . 2017. Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management. NICE Guideline [NG80]https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng80 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization WHO speaks at the European Parliament on the COVID-19 response. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-06-2020-who-speaks-at-the-european-parliament-on-the-covid-19-response Available from:

- 8.Wise J. Covid-19: risk of second wave is very real, say researchers. BMJ. 2020;369:2294. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams S.L., Ames K., Lawson C. Preferences and trust in traditional and non-traditional sources of health information–a study of middle to older aged Australian adults. J Communication Healthcare. 2019;12:134–142. [Google Scholar]