Abstract

Youth represent 21% of new HIV diagnoses in the United States. Gay, bisexual, and transgender (GBT) youth, particularly those from communities of color, and youth who are homeless, incarcerated, in institutional settings, or engaging in transactional sex are most greatly impacted. Compared with adults, youth have lower levels of HIV serostatus awareness, uptake of antiretroviral therapy (ART), and adherence. Widespread availability of ART has revolutionized prevention and treatment for both youth at high risk for HIV acquisition and youth living with HIV, increasing the need to integrate behavioral interventions with biomedical strategies. The investigators of the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (ATN) completed a research prioritization process in 2019, focusing on research gaps to be addressed to effectively control HIV spread among American youth. The investigators prioritized research in the following areas: (1) innovative interventions for youth to increase screening, uptake, engagement, and retention in HIV prevention (eg, pre-exposure prophylaxis) and treatment services; (2) structural changes in health systems to facilitate routine delivery of HIV services; (3) biomedical strategies to increase ART impact, prevent HIV transmission, and cure HIV; (4) mobile technologies to reduce implementation costs and increase acceptability of HIV interventions; and (5) data-informed policies to reduce HIV-related disparities and increase support and services for GBT youth and youth living with HIV. ATN’s research priorities provide a roadmap for addressing the HIV epidemic among youth. To reach this goal, researchers, policy makers, and health care providers must work together to develop, test, and disseminate novel biobehavioral interventions for youth.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, adolescents

Introduction

The HIV Epidemic in the United States

HIV infections among adolescents and young adults aged 13 to 24 years have more than doubled in the last 15 years, and these individuals represented 21% of the epidemic population (approximately 7100 infected youth) in the United States in 2018 [1-3]. Gay, bisexual, and transgender (GBT) youth represented up to 70% of new infections among youth in 2017. Among GBT youth, 37% were Black youth and 29% were Hispanic/Latino youth in terms of race/ethnicity, whereas 28% were White youth [3]. HIV also disproportionally impacts other marginalized youth, including those who are homeless, those who are incarcerated, those placed in foster care or other types of institutions, and those who engage in transactional sex [4-18]. Furthermore, there are geographic disparities in new HIV diagnoses. As reflected in the Ending the HIV Epidemic Initiative, southern states accounted for 52% of new HIV diagnoses in 2017 [19]. To stop HIV among adolescents, it is essential to routinely engage youth at the highest risk for HIV in prevention strategies and to achieve and sustain viral suppression in all youth living with HIV.

HIV Prevention and Treatment Continua

There are sequenced steps, referred to as the HIV treatment continuum and the HIV prevention continuum, that provide a metric for monitoring success toward ending the HIV epidemic. The first step in the HIV treatment continuum is to identify youth living with undiagnosed HIV infection. To achieve this, youth at high risk for HIV acquisition need to be tested for HIV every 3 months. However, 60% of youth living with HIV remain undiagnosed, and this is the highest rate in any age group [2]. Once diagnosed, the next steps are to ensure that youth living with HIV are linked to care, receive antiretroviral therapy (ART), and are regularly monitored so they can achieve viral suppression. ART, which is more effective and easier to take than before, improves quality of life and reduces early mortality. Furthermore, when youth achieve viral suppression, the risk of HIV transmission is reduced [9,10]. Impressively, about two-thirds (68%) of youth living with HIV are linked to care within 1 month of their diagnosis [13]. Among youth in care, 98% were prescribed antiretroviral therapy and 89% achieved viral suppression at 1 year [13]. However, less than half (34%-44%) of youth living with HIV are retained in HIV care for a year or more, and viral suppression among youth living with HIV is only about 16% at 5 years after diagnosis (compared with 58% among adults) [14,15], indicating that linkage to care is insufficient to achieve and sustain viral suppression [20].

Similar to the HIV treatment continuum, the HIV prevention continuum involves several key steps [21]. These include (1) access to health care; (2) regular HIV testing for youth at high risk, especially among GBT youth; (3) adoption of prevention strategies, such as condom use, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) for one time acute exposure; and (4) retention and adherence to these prevention strategies over time. Many youth, especially GBT youth, have limited access to health care. Approximately one in three GBT youth between 12 and 17 years of age do not receive preventive care, and one in three do not seek or receive care within a year of symptom onset for a health problem [16,18,22]. Youth who need PrEP are those least aware of and least likely to use PrEP [17,18]. Despite the demonstration of PrEP acceptability among GBT youth [23], PrEP utilization estimated from 2017 national data was only 9.4% among young men who have sex with men (MSM) compared with 19.9% among all MSM [24]. Although the proportion of health care providers prescribing PrEP in the United States has risen to 24%, differences in PrEP use between racial/ethnic groups remain, with a use percentage of 26% among eligible Black MSM versus 42% among White MSM [25]. Moreover, once initiated, PrEP adherence has been found to be suboptimal among young MSM, even when paired with tailored behavioral interventions [23,26].

In light of the suboptimal utilization of the treatment and prevention continua, the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (ATN) identified research gaps and defined five priority areas to guide its research agenda. The ATN is the only domestic research network (established in 2001) focused on youth at high risk for HIV and youth living with HIV (age 12-24 years). In this paper, we outline ATN’s research agenda for reducing new HIV infections among youth in the United States.

Overview of the ATN

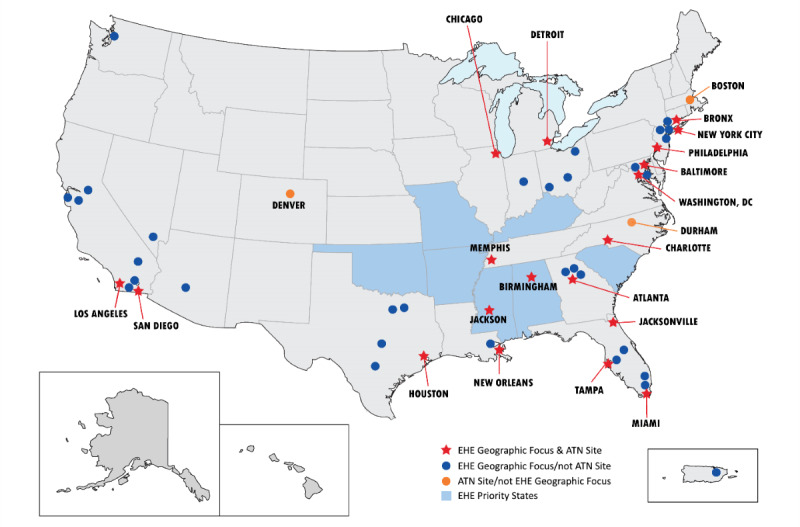

The ATN is a collaborative National Institutes of Health (NIH)–supported research network with the goal of reducing the number of HIV infections among youth by (1) increasing the number of youth who know their HIV status; (2) developing, testing, and scaling up sustained use of biobehavioral approaches (condoms, PrEP, and PEP) among youth at high risk for HIV; and (3) increasing the number of youth living with HIV who achieve and sustain viral suppression. The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development provides the primary financial support for this network; additional resources are provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. As shown in Figure 1, ATN sites are located in heavily impacted areas, many of which were identified in the Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America (EHE) initiative [27]. These sites reflect the concentration and the distribution of youth living with HIV nationally.

Figure 1.

Map of Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions study sites and Ending the HIV Epidemic geographic areas.

First established in 2001, the ATN is in its fourth project period. Currently, the ATN is comprised of three thematically focused peer-reviewed Research Program Grants (U19) (Scale It Up, CARES, and iTech), a Coordinating Center (U24), a number of independent and cross-network research protocols managed by the U24, a Diversity Scholars Program, and several cross-network working groups. The ATN facilitates the sharing of ideas, data, scientific expertise, and specialized resources, such as equipment, services, and clinical facilities. Although all ATN protocols address one or more steps in the HIV treatment and/or prevention continua, they are addressed through the thematic lens of their managing U19. Thus, research projects are complementary and act synergistically to achieve the network’s goals (a list of currently funded ATN projects can be found on the ATN website) [28]. A brief summary of each U19 is provided below.

ATN Scale It Up includes six studies specifically focused on implementation science and the process of improving self-management among youth [29]. This multisite U19 identifies and builds on efficacious and effective interventions to improve self-management among youth at high risk for HIV infection and youth living with HIV. One of its goals is to develop, test, and disseminate new methods for implementation and analysis with strong theoretical foundations, such as tailored motivational interviewing to help adolescent medicine providers advance the movement of their patients across the treatment and care continua. To attain this goal across all the interventions being tested in Scale It Up, researchers are assessing how youth self-management varies over time, is improved by interventions, and mediates intervention effects.

CARES is focused on identifying and leveraging novel community-based settings to act as gateways where youth at high risk and youth living with HIV can be engaged in HIV prevention and treatment [30]. Youth recruited into one of CARES’ three studies complete a behavioral assessment and are tested for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) every 4 months. Both seronegative youth and youth living with HIV enrolled in the studies receive a stepped care model of increasingly intensive interventions, which include text messaging and mobile self-assessment, peer support through social media groups, and interpersonal coaching. This stepped care model has been successfully used with other chronic diseases [31-33], and CARES is evaluating the model’s efficacy for HIV prevention and treatment.

iTech aims to lower the burden of HIV infection by developing and evaluating innovative interdisciplinary research on technology-based interventions across the HIV prevention and care continua for youth at high risk or youth living with HIV [34]. Each of iTech’s 11 research projects includes the use of technological innovations (eg, apps/mobile websites, videoconferencing/telehealth, and home-based HIV/STI testing) to advance the field. The iTech objectives are discussed in more detail under the Technology section below.

The Coordinating Center provides support, coordination, and operational infrastructure to the three ATN research programs and provides expertise in project management, data management, and statistics to the ATN [35]. The Coordinating Center manages multiple network studies, collaborating with principal investigators and project sites at health care organizations and universities around the country.

Development of the ATN Research Priorities

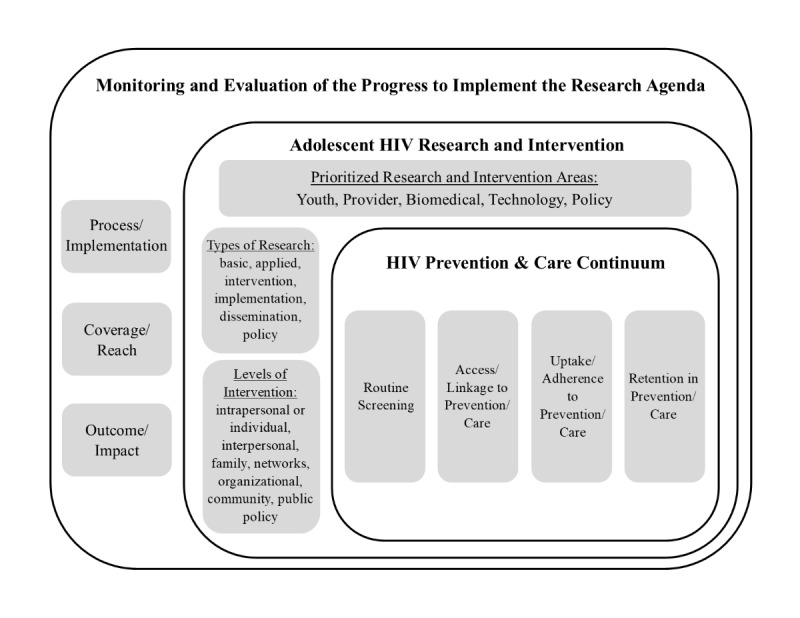

The Executive Committee (EC), the leadership and governing body of the ATN, is comprised of representatives from each U19, the Coordinating Center, participating National Institutes of Health, selected scientific experts, and community youth representatives. The EC identifies emergent scientific priorities, defines the research agenda, and fosters collaboration with other HIV research networks and investigators. To begin the research prioritization process, the EC held a series of conference calls, workshops, presentations, and meetings. Furthermore, the EC surveyed ATN investigators and consulted with scientific experts outside of the EC to identify the key research issues, priorities, and knowledge gaps regarding the adolescent HIV/AIDS epidemic in the country. The EC completed the research prioritization process in 2019 and identified the following five priority research areas: (1) innovative strategies to engage youth in HIV treatment and prevention, (2) health systems and provider interventions, (3) biomedical interventions, (4) technology, and (5) data-informed policies. A nested model (Figure 2) was also created to illustrate the complex set of factors that need to be considered in attempting to implement and evaluate the newly developed research plan.

Figure 2.

A nested model of the research needed to defeat the rising HIV epidemic among adolescents and young adults in the United States. This model includes the primary targeted outcomes to achieve reductions in HIV among youth at high risk and viral suppression among youth living with HIV.

At the core of the nested model lies the continua of care elements for both HIV prevention and HIV treatment, since these are the focal points for ATN’s research and intervention work. At the next level are our prioritized research areas that could be applied to all of the factors within the continua of care. Also included in this level are descriptions of the various types of research that could be conducted in order to explore prioritized research areas (ie, basic, applied, intervention, implementation, dissemination, and policy) and the levels at which ATN’s research and interventions could be focused (ie, intrapersonal or individual, interpersonal, family, networks, organizational, community, and public policy). The outermost level demonstrates the need to continually monitor and evaluate the research agenda to assess its utility and to offer insights for needed adjustments. We suggest that such monitoring and evaluation should occur at three different levels in order to ensure maximum benefit to adolescents, including process/implementation, coverage/reach, and outcome/impact.

Three principles emerged that guided our thinking as we developed the research priorities. First, the recognition that segmenting by serostatus was no longer salient since the approaches (eg, sustained health care engagement and ART adherence for PrEP or treatment as prevention) needed to promote movement along the HIV treatment continuum for youth living with HIV and the HIV prevention continuum for youth at risk are similar. Second, at each step on these continua, youth often confront multiple barriers to care that may stem from personal and interpersonal issues, societal/community norms, structural factors, and challenges with the health care system. Furthermore, the salience of these barriers varies by geography, context, and sociocultural contexts. Third, there are concurrent developmental processes unfolding during adolescence. Youth are most likely to first initiate risky behaviors that lead to HIV acquisition or transmission during adolescence, including sexual activity without a condom, and alcohol and drug use [36-38]. Adolescence is also the period of onset of many lifelong mental health challenges, particularly among sexual, gender, racial, and ethnic minority youth [39]. These developmental trajectories offer opportunities for interventions, such as comprehensive sex and substance abuse prevention, and age-appropriate and culturally sensitive HIV-prevention programs [40]. The developmental processes are more complicated for GBT youth, who face additional challenges stemming from their marginalized and stigmatized sexual orientation [41-44]. For instance, unlike their heterosexual peers, GBT youth must decide who, when, how, where, and what to disclose regarding their sexual orientation and/or their HIV status [45,46].

ATN’s Priority Research Areas

Overview

In this section, we describe each research priority area and highlight some of ATN’s efforts to address them. It is important to note that the ATN regularly reviews these research priorities to ensure that they continue to be responsive to scientific advances, changes in the epidemic of HIV, and emerging needs in the youth we serve.

Innovative Strategies to Engage Youth in HIV Treatment and Prevention

Engaging youth in interventions to increase their uptake, adherence, and retention with HIV treatment and prevention services poses great challenges but remains a critical research priority. It has long been known that community agencies and venues where youth congregate are fruitful settings for engaging youth [47,48]. Providing safe and affirming spaces where youth can receive culturally congruent support and services can promote engagement of HIV prevention and treatment services [49]. The importance of using text messages and social media platforms and apps for engaging and retaining youth is increasing [50-54]. Recent community mobilization programs, focused on addressing structural-level factors to improve HIV testing and prevention, yielded mixed results [55-57].

Leveraging and expanding this knowledge, ATN investigators have launched innovative studies that are examining social media–based strategies for engaging, recruiting, and retaining youth in research studies and testing technology-based interventions. For example, one current ATN project focuses on helping youth living with HIV secure jobs through vocational training to overcome socioeconomic barriers to health care [58]. ATN studies are focusing on how to more effectively reach youth with adaptations or novel delivery strategies of evidence-based interventions that are lower cost, more attractive, and more accessible, while having a greater impact on decreasing HIV transmission and acquisition, and increasing engagement and adherence to therapeutic and preventive interventions.

Implementation science research is one of the most important approaches for optimizing interventions and maximizing their impact on youth at high risk for HIV acquisition and youth living with HIV. The ATN employs innovative methods, such as implementation-effectiveness hybrids, to address effectiveness and implementation along the same timeline [59]. The portfolio of current ATN studies also includes interventions that were designed with dissemination in mind. They can be scaled rapidly, reduce the need to precisely replicate a manualized intervention, and focus on each youth’s personal risks, tailoring the work to address the variability that occurs across and between communities [60,61]. The studies also build on evidence-based interventions systematically assembled and disseminated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), and Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) to identify the most robust intervention components for wider utilization and scale-up.

Health Systems and Provider Interventions

Although researchers have identified that adolescents prefer medical care that is local, integrated, quick, confidential, nonprejudicial, hassle-free, and inexpensive [62,63], this type of care is yet to become widely available. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) youth face particular challenges in accessing and receiving culturally affirming health care services, as health care providers and others with whom youth interact in care settings may hold stigmatizing views of LGBTQ youth [64-66]. Such forms of stigma perpetuated by health care providers and others in clinical settings have been shown to be barriers to seeking health care, especially among transgender young people [67-69]. These challenges may be exacerbated for LGBTQ youth of color, as racism is a form of intersectional stigma that negatively impacts access to health care, especially for Black LGBTQ youth [65,70,71]. Clinical providers can play a pivotal role in promoting change within their organization, reducing stigma, and increasing youths’ engagement and progression through the HIV prevention and care continua. Health system and provider interventions can promote changes in practice as well as in care settings. For example, training medical, clerical, and administrative staff to be culturally responsive to GBT youth clients successfully transformed policies and protocols of a set of health care agencies [72]. Providing feedback on the perceived quality of a clinic’s care and services can also improve the quality of care and the services provided. For example, a current ATN project in iTech sends “mystery shoppers,” adolescent consumer advocates, to visit existing HIV testing sites to evaluate their HIV counseling and testing services according to a number of youth-focused dimensions. Testing sites receive informational reports that they can use to improve service delivery [73].

Despite the efficacy of PrEP and PEP in reducing HIV acquisition, some providers are reticent to prescribe these medications to youth because they are concerned about risk compensation (ie, adjusting one’s behavior according to the perceived level of risk), nonadherence, and ART toxicities [74,75]. Other providers have expressed concerns regarding prescribing PrEP and ART to substance users [76]. Clearly, provider-based interventions to promote PrEP and PEP are needed. Although several approaches for scaling up PrEP and PEP in youth have been developed [77,78], they are yet to be widely disseminated and some are yet to be rigorously evaluated. For instance, public health jurisdictions, such as the New York City Health Department, are using academic detailing, a strategy typically used by pharmaceutical companies that engages providers in their work setting, to efficiently educate providers about PrEP [79,80]. Interventions to help providers to deliver culturally affirming care to GBT youth are also needed. Although there are many text and web resources to promote the use of PrEP among primary care providers, the efficacy of these programs to improve practice and services for youth has not been fully evaluated [81-83]. TMI, one of the studies in Scale it Up, addresses this need.

Biomedical Interventions

PrEP, PEP, and treatment as prevention have become important biomedical interventions that can either protect youth from becoming infected or ensure longer life and higher quality of life for youth living with HIV [9,84,85]. The first trials of PrEP (tenofovir plus emtricitabine) in 15- to 21-year-old youth at high risk for HIV infection, conducted by the ATN, demonstrated that PrEP offered high levels of protection for youth who were adherent and did not identify safety concerns [26,86,87]. Concerns related to long-term adherence to daily oral therapy has led researchers to examine the efficacy of long-acting antiretroviral agents, particularly injectable formulations of ART, which are currently being evaluated in phase III studies with adults, and broadly neutralizing antibodies, which are currently in phase IIb testing [88-90]. To help ensure that these novel formulations are approved for youth, the ATN is collaborating with the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) to examine the acceptability, tolerability, and adherence to injectable cabotegravir in youth. Because of its experience navigating the ethical, legal, and regulatory issues associated with the participation of youth in trials of biomedical interventions, the ATN has and will continue to play a pivotal role in advancing biomedical prevention efforts for youth [91,92].

HIV vaccine research and the development of immune-based and topical microbicidal–based therapies are other promising biomedical interventions [93-97]. Basic and clinical scientists have made major developments in knowledge about HIV reservoirs and interventions for an HIV cure, although attempts to achieve a cure have been unsuccessful to date [98,99]. One of the studies in the CARES U19 focuses on treatment of acutely infected youth, comparing their viral reservoirs over time to those of youth with established infections who were treatment naive. This project will provide important data on developmentally linked immunological processes associated with early and sustained viral suppression. Additionally, there has been an improved understanding of the role of the mucosal microbiome, semen exposure, and STIs in the risk of HIV acquisition and transmission [100]. The most futuristic approaches are studies of gene editing, which look to either eliminate the CCR5 gene or mutate the HIV virus successively so that it is no longer robust and easily transferable [101]. When these interventions are ready for testing, the ATN is well positioned to initiate trials of these biomedical studies in collaboration with researchers conducting trials with adults.

Technology

Technology use is ubiquitous among adolescents; thus, its power and reach can be harnessed for interventions targeting each stage of the prevention and care continua. Technology offers unique opportunities to recruit, engage, and retain adolescents in research through provision of tailored messages, inclusion of game-based elements, and delivery of personalized theory-based intervention components and health content [102]. Given that more than 96% of youth aged 18 to 29 years in the United States have smartphones and regularly use the internet for a variety of activities, interventions delivered through the internet and mobile phones are highly acceptable to youth [103,104]. Although the costs for initial start-up and development of technology-based interventions are high, once developed, the associated costs of adaptation and dissemination are more moderate. It is not surprising that the number of researchers developing and testing internet- and app-based HIV interventions is rapidly increasing. Unfortunately, these efforts are not well coordinated, and there is a proliferation of similar apps or websites that fail to make novel contributions or address unanswered questions [105,106].

Each ATN U19 program (iTech, CARES, and Scale it Up) is developing and evaluating innovative technology–based interventions across the HIV prevention and care continua. iTech focuses on the evaluation of technologically oriented and youth-oriented interventions, with each project utilizing mobile technologies, including apps, mobile-optimized websites, and online video counseling. The apps within iTech are tailored to the population addressed (eg, seronegative youth and youth living with HIV), the targeted health outcome (eg, PrEP uptake or adherence, engagement with health care, and viral suppression), and the technology platform utilized. iTech will foster the identification of the specific features across apps that are most used and most useful for specific populations. Using a harmonized set of technology-focused metrics and paradata for evaluation and cost-effectiveness analyses, iTech represents a coordinated effort that will allow for more impactful technology-based interventions. For example, one of its projects is a three-arm, randomized, controlled trial that is testing the efficacy of P3 (Prepared, Protected, emPowered), a novel, theory-based mobile app to promote PrEP adherence through social networking and gamification. This app utilizes game mechanics (rewards and unlocking app features) and social networking/peer support to also improve retention in PrEP clinical care and PrEP persistence among GBT youth [107].

In contrast, CARES adopted low-cost, scalable, device-agnostic platforms that are utilized across all subpopulations and outcomes, with a focus on personalizing risk messages within platforms. Personalized messaging will be the same regardless of the delivery format (text message, phone call, and video chat). CARES interventions combine text messages and peer-support chat rooms with more traditional counseling methods. The CARES approach focuses on messages and probes, which address the following core functions of behavioral change: establish a framework for change, convey necessary information, build self-management skills, address barriers, and provide tools and support. Scale It Up is conducting an effectiveness trial, called SMART, of an intervention comparing text messaging and cell phone support to improve HIV medication adherence among youth living with HIV. Youth are recruited and enrolled online, using social media and app-based approaches. Across all ATN projects, the opportunity to provide a tailored suite of technology-based tools is a useful and innovative way to engage youth at high risk or youth living with HIV to improve HIV-related prevention and treatment outcomes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Technology-based tools utilized in ATN studies.

| Name of the study | Brief description of technology-based tools | Associated theories | Targeted outcomes | Research program |

| YouThrive | Web app including peer support via social networking, daily tips for living with HIV, self-monitoring tools, and goal setting/tracking | Information, motivation, and behavioral skills model | Viral suppression | iTech |

| Get Connected | Web app with content tailored to demographic characteristics, HIV/STIa risk behaviors, and sociocultural contexts of individual participants | Integrated behavior model and self-determination theory | Uptake of HIV prevention services, PrEPb awareness, and willingness | iTech |

| LYNX | Mobile app including personalized HIV risk scores, HIV/STI testing, and prevention information | Information, motivation, and behavioral skills model | HIV/STI testing and PrEP uptake | iTech |

| My Choices | Mobile app including tools for tracking HIV risk, HIV/STI testing, and prevention information | Social cognitive theory | HIV/STI testing and PrEP uptake | iTech |

| P3 | Mobile app utilizing game mechanics and social networking features P3+ includes provision of in-app adherence coaching |

Social cognitive theory and Fogg behavioral model | PrEP adherence, retention in PrEP care, and PrEP persistence | iTech |

| SMART | Comparison of text messaging–based and cell phone–based adherence support | Supportive accountability model | Viral suppression and adherence self-management | Scale It Up |

| TMI | Automatic feedback reports to providers to improve motivational interviewing competency | Modeling, rehearsal (verbal/behavioral), and feedback strategies | Motivational interviewing competency | Scale It Up |

| Stepped Care for Youth | Stepped care intervention utilizing text messaging and monitoring, peer support via online social networks, and e-coaching | N/Ac | Viral suppression | CARES |

| Engaging Seronegative Youth | Text messaging and monitoring, peer support via online social networks, and e-coaching | N/A | HIV/STI testing, PrEP uptake, and adherence | CARES |

| Triggered Escalating Real-time Adherence (TERA) | Electronic dose monitoring, adherence monitoring via text messaging, and e-coaching as needed | Therapeutic drug monitoring | ART adherence and viral suppression | Coordinating Center |

| ePrEP | Mobile app–based home care system for PrEP prescription and care | Anderson behavioral model adapted to HIV care | PrEP adherence, retention in PrEP care, and PrEP persistence | iTech |

| TechStep | Stepped care intervention utilizing text messaging, a web app, and e-coaching | Information, motivation, and behavioral skills model | PrEP uptake and reduction of HIV risk behaviors | iTech |

aSTI: sexually transmitted infection.

bPrEP: pre-exposure prophylaxis.

cN/A: not applicable.

Data-Informed Policies

Actionable policies are optimally derived from and shaped by data. Fortunately, many of the recent state and federal policy shifts in the United States reflect the belief that youth should be empowered to advocate and take individual responsibility for their health. Some of these shifts include expanding minors’ authority to consent to health care, including care related to sexual activity and STIs, HIV testing and treatment, and the constitutional right to privacy regarding a minor’s decision to obtain contraceptives [108].

Most states today have a policy requiring some form of HIV education. Federally funded school-based HIV prevention programs typically do not address issues related to GBT youth and thus are not relevant for these youth [109,110]. For instance, many state-supported abstinence-only programs exclude discussions of same-gender sexuality (eg, State Abstinence Education Grant Program). Furthermore, the efficacy of such programs to reduce STI incidence and HIV prevalence has not been established since the majority of evaluations were not powered to detect changes in biological outcomes. A recent meta-analysis of school-based interventions reported that only one of seven programs reduced STI incidence and none decreased HIV incidence [111]. Thus, rigorous evaluation of multilevel school-based programs is being considered as a future ATN research priority.

Evidence on the relationship between school climate and hate crimes should be used to inform and create policies to monitor the increase and levy consequences for discriminatory acts against marginalized groups such as GBT youth. Similarly, policies to create safe spaces for GBT youth and monitor the success of engaging GBT youth and other youth at high risk for HIV acquisition should also be enacted [112]. There is evidence that in jurisdictions with more affirming LGBTQ school climates, these youth reported fewer days of episodic drinking and fewer drinking days at school [113]. The ATN is gathering and disseminating data to policy makers, public health officials, and other officials to make informed decisions and implement efficacious HIV prevention and treatment models for US youth. The Community-Engaged Dissemination and Implementation Research (CEDI) Workgroup is working in collaboration with ATN members to translate their evidence-based research findings for dissemination and implementation in clinic and community settings, and to inform policy and advocacy for delivery of care. Another example is the work being conducted by the ATN Modeling Core, which is developing a detailed health policy mathematical model to monitor and evaluate HIV in adolescents and young adults. The Modeling Core is using a novel approach to microsimulation modeling of HIV disease progression, patterns of care, and treatment outcomes, and applying innovative statistical methods to populate the model with data about patterns of health care, HIV viral load trajectories, and ART derived from completed ATN studies and other national studies. This model will be used to evaluate the potential clinical and economic impacts of ATN intervention trials to support medication adherence, retention in care, and improved clinical outcomes for youth living with HIV and inform decision makers [114,115].

Responsiveness to Emerging Needs

While the current ATN agenda focuses on community and provider interventions that are acceptable to youth and scalable at the national level, the network’s structure is nimble enough to allow for additional high-priority studies generated internally within the network and/or in collaboration with other networks, agencies, and outside investigators. The EHE identified several focus and geographical areas where ATN investigators and research programs can contribute [27]. Taking the EHE focus areas into consideration, the network solicited research studies in 2019 that included a focus on (1) conducting assessments that use an implementation science framework, (2) expanding ongoing efforts in EHE geographic areas to reach underserved youth, or (3) building connections with health departments and other community-based partners in EHE geographic areas.

New projects resulting from this allow the network to increase its youth research portfolio in focused EHE geographic areas where ATN is currently not represented and to contribute to efforts to end the HIV epidemic. The ATN will continue to regularly review its priorities and launch new studies in response to changing needs, scientific advances, and epidemiological shifts in HIV incidence.

Conclusions

This paper describes the top five research priority areas guiding ATN’s efforts to address the domestic HIV epidemic in youth. Monitoring implementation and progress from current ATN projects requires ongoing monitoring of the indicators of coverage and outcomes as youth progress through the HIV prevention and care continua, and targeting efforts in areas most heavily impacted such as EHE hotspots. Addressing the research agenda and key priority areas for youth at high risk for HIV infection and youth living with HIV also necessitates ongoing collaborations between academic research institutions, health care providers, community-based organizations, impacted communities, and youth in the United States, as well as scientific leadership and expertise on state-of-the-art HIV prevention and care research for adolescents through the ATN.

Acknowledgments

This report was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, and the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions Executive Committee. The comments and views of the authors do not necessarily represent the views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Abbreviations

- ATN

Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions

- ART

antiretroviral therapy

- EC

Executive Committee

- EHE

Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America

- GBT

gay, bisexual, and transgender

- LGBTQ

lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer

- MSM

men who have sex with men

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- PAW

Policy and Advocacy Workgroup

- PEP

postexposure prophylaxis

- PrEP

pre-exposure prophylaxis

- STI

sexually transmitted infection

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: ACS receives support from a Gilead FOCUS grant. The other authors have no conflicts to declare.

References

- 1.HIV Surveillance Reports: Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2015. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [2017-01-27]. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html.

- 2.HIV Among Youth. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [2017-01-27]. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/youth/index.html.

- 3.HIV and Gay and Bisexual Men. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [2017-01-27]. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/msm/index.html.

- 4.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Song J, Gwadz M, Lee M, Van Rossem R, Koopman C. Reductions in HIV risk among runaway youth. Prev Sci. 2003 Sep;4(3):173–87. doi: 10.1023/a:1024697706033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romero EG, Teplin LA, McClelland GM, Abram KM, Welty LJ, Washburn JJ. A longitudinal study of the prevalence, development, and persistence of HIV/sexually transmitted infection risk behaviors in delinquent youth: implications for health care in the community. Pediatrics. 2007 May;119(5):e1126–41. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0128. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/17473083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahrens KR, McCarty C, Simoni J, Dworsky A, Courtney ME. Psychosocial pathways to sexually transmitted infection risk among youth transitioning out of foster care: evidence from a longitudinal cohort study. J Adolesc Health. 2013 Oct;53(4):478–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.05.010. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/23859955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerassi LB, Jonson-Reid M, Plax K, Kaushik G. Trading Sex for Money or Compensation: Prevalence and Associated Characteristics from a Sexually Transmitted Infection (STI) Clinic Sample. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2016;25(9):909–920. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2016.1223245. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28190952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lightfoot M, Rotheram-Borus M. Interventions for High-Risk Youth. In: Peterson JL, DiClemente R, editors. Handbook of HIV Prevention. New York: Springer US; 2000. pp. 129–145. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: Recommendations for a public health approach. World Health Organization. 2016. [2017-01-27]. https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/arv/arv-2016/en/ [PubMed]

- 10.Cohen J. Breakthrough of the year. HIV treatment as prevention. Science. 2011 Dec 23;334(6063):1628. doi: 10.1126/science.334.6063.1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sutton SS, Magagnoli J, Hardin JW. Odds of Viral Suppression by Single-Tablet Regimens, Multiple-Tablet Regimens, and Adherence Level in HIV/AIDS Patients Receiving Antiretroviral Therapy. Pharmacotherapy. 2017 Feb;37(2):204–213. doi: 10.1002/phar.1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bangsberg DR. Less than 95% adherence to nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor therapy can lead to viral suppression. Clin Infect Dis. 2006 Oct 01;43(7):939–41. doi: 10.1086/507526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.HIV Surveillance Reports Archive: Monitoring Selected National HIV Prevention and Care Objectives by Using HIV Surveillance Data, United States and 6 Dependent Areas, 2015. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [2017-01-27]. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance-archive.html#supplemental-archive.

- 14.Zanoni BC, Mayer KH. The adolescent and young adult HIV cascade of care in the United States: exaggerated health disparities. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014 Mar;28(3):128–35. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0345. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24601734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minniear TD, Gaur AH, Thridandapani A, Sinnock C, Tolley EA, Flynn PM. Delayed Entry into and Failure to Remain in HIV Care Among HIV-Infected Adolescents. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2013 Jan;29(1):99–104. doi: 10.1089/aid.2012.0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahana SY, Fernandez MI, Wilson PA, Bauermeister JA, Lee S, Wilson CM, Hightow-Weidman LB. Rates and correlates of antiretroviral therapy use and virologic suppression among perinatally and behaviorally HIV-infected youth linked to care in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015 Feb 01;68(2):169–77. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000408. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25590270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strauss BB, Greene GJ, Phillips G, Bhatia R, Madkins K, Parsons JT, Mustanski B. Exploring Patterns of Awareness and Use of HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Among Young Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Behav. 2017 May;21(5):1288–1298. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1480-0. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/27401537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eaton LA, Driffin DD, Bauermeister J, Smith H, Conway-Washington C. Minimal Awareness and Stalled Uptake of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Among at Risk, HIV-Negative, Black Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015 Aug;29(8):423–9. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0303. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26083143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.HIV in the United States by Region. US Center for Disease Control and Prevention. [2017-01-27]. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/geographicdistribution.html.

- 20.Kapogiannis BG, Koenig LJ, Xu J, Mayer KH, Loeb J, Greenberg L, Monte D, Banks-Shields M, Fortenberry JD, Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions The HIV Continuum of Care for Adolescents and Young Adults Attending 13 Urban US HIV Care Centers of the NICHD-ATN-CDC-HRSA SMILE Collaborative. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020 May 01;84(1):92–100. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McNairy ML, El-Sadr WM. A paradigm shift: focus on the HIV prevention continuum. Clin Infect Dis. 2014 Jul;59 Suppl 1:S12–5. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu251. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24926026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nordin JD, Solberg LI, Parker ED. Adolescent primary care visit patterns. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(6):511–6. doi: 10.1370/afm.1188. http://www.annfammed.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=21060121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hosek SG, Rudy B, Landovitz R, Kapogiannis B, Siberry G, Rutledge B, Liu N, Brothers J, Mulligan K, Zimet G, Lally M, Mayer KH, Anderson P, Kiser J, Rooney JF, Wilson CM, Adolescent Trials Network (ATN) for HIVAIDS Interventions An HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Demonstration Project and Safety Study for Young MSM. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017 Jan 01;74(1):21–29. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001179. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/27632233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sullivan PS, Sanchez TH, Zlotorzynska M, Chandler CJ, Sineath RC, Kahle E, Tregear S. National trends in HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis awareness, willingness and use among United States men who have sex with men recruited online, 2013 through 2017. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020 Mar;23(3):e25461. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25461. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32153119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang C, McMahon J, Fiscella K, Przybyla S, Braksmajer A, LeBlanc N, Liu Y. HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Implementation Cascade Among Health Care Professionals in the United States: Implications from a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2019 Dec 01;33(12):507–527. doi: 10.1089/apc.2019.0119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hosek SG, Landovitz RJ, Kapogiannis B, Siberry GK, Rudy B, Rutledge B, Liu N, Harris DR, Mulligan K, Zimet G, Mayer KH, Anderson P, Kiser JJ, Lally M, Brothers J, Bojan K, Rooney J, Wilson CM. Safety and Feasibility of Antiretroviral Preexposure Prophylaxis for Adolescent Men Who Have Sex With Men Aged 15 to 17 Years in the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2017 Nov 01;171(11):1063–1071. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2007. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28873128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ending the HIV Epidimic: Plan for America. HIV.gov. [2020-09-30]. https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/overview.

- 28.The Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (ATN) [2020-12-02]. https://atnweb.org/atnweb/

- 29.Scale It Up. [2020-09-30]. https://www.etr.org/scaleitup/

- 30.ATN CARES. [2020-09-30]. https://www.atncares.org/

- 31.Von Korff M, Tiemens B. Individualized stepped care of chronic illness. West J Med. 2000 Feb;172(2):133–7. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.172.2.133. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/10693379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Simon G, Walker E, Unützer J, Bush T, Russo J, Ludman E. Stepped collaborative care for primary care patients with persistent symptoms of depression: a randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999 Dec;56(12):1109–15. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bair MJ, Ang D, Wu J, Outcalt SD, Sargent C, Kempf C, Froman A, Schmid AA, Damush TM, Yu Z, Davis LW, Kroenke K. Evaluation of Stepped Care for Chronic Pain (ESCAPE) in Veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan Conflicts: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 May;175(5):682–9. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.The UNC/Emory Center for Innovative Technology (iTech) [2020-09-30]. https://itechnetwork.org/

- 35.Collaborative Studies Coordinating Center. [2020-11-28]. https://sites.cscc.unc.edu/cscc/

- 36.Arain M, Haque M, Johal L, Mathur P, Nel W, Rais A, Sandhu R, Sharma S. Maturation of the adolescent brain. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:449–61. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S39776. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S39776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crone EA, Dahl RE. Understanding adolescence as a period of social-affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012 Sep;13(9):636–50. doi: 10.1038/nrn3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mutumba M, Harper GW. Mental health and support among young key populations: an ecological approach to understanding and intervention. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(2 Suppl 1):19429. doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.2.19429. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25724505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dahl RE. Adolescent brain development: a period of vulnerabilities and opportunities. Keynote address. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004 Jun;1021:1–22. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Almeida J, Johnson RM, Corliss HL, Molnar BE, Azrael D. Emotional distress among LGBT youth: the influence of perceived discrimination based on sexual orientation. J Youth Adolesc. 2009 Aug 24;38(7):1001–14. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9397-9. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/19636742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaufman M. Adolescent sexual orientation. Paediatr Child Health. 2008 Sep;13(7):619–30. doi: 10.1093/pch/13.7.619. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/19436504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bry LJ, Mustanski B, Garofalo R, Burns MN. Resilience to Discrimination and Rejection Among Young Sexual Minority Males and Transgender Females: A Qualitative Study on Coping With Minority Stress. J Homosex. 2018;65(11):1435–1456. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2017.1375367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Earnshaw VA, Reisner SL, Juvonen J, Hatzenbuehler ML, Perrotti J, Schuster MA. LGBTQ Bullying: Translating Research to Action in Pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2017 Oct;140(4) doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0432. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=28947607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Fernandez MI. Sexual orientation and developmental challenges experienced by gay and lesbian youths. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1995;25 Suppl:26–34; discussion 35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.D'Angelo LJ, Abdalian SE, Sarr M, Hoffman N, Belzer M, Adolescent Medicine HIV/AIDS Research Network Disclosure of serostatus by HIV infected youth: the experience of the REACH study. Reaching for Excellence in Adolescent Care and Health. J Adolesc Health. 2001 Sep;29(3 Suppl):72–9. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00285-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marano MR, Stein R, Williams WO, Wang G, Xu S, Uhl G, Cheng Q, Rasberry CN. HIV testing in nonhealthcare facilities among adolescent MSM. AIDS. 2017 Jul 01;31 Suppl 3:S261–S265. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001508. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28665884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rotheram-Borus MJ. Expanding the range of interventions to reduce HIV among adolescents. AIDS. 2000 Jun;14 Suppl 1:S33–40. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanner AE, Philbin MM, Duval A, Ellen J, Kapogiannis B, Fortenberry JD, Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions "Youth friendly" clinics: considerations for linking and engaging HIV-infected adolescents into care. AIDS Care. 2014 Feb;26(2):199–205. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.808800. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/23782040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bassett IV, Wilson D, Taaffe J, Freedberg KA. Financial incentives to improve progression through the HIV treatment cascade. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2015 Nov;10(6):451–63. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000196. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26371461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Horvath T, Azman H, Kennedy GE, Rutherford GW. Mobile phone text messaging for promoting adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Mar 14;(3):CD009756. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009756. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22419345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Pachankis JE, Gamarel KE, Surace A, Golub SA, Parsons JT. Feasibility, Acceptability, and Preliminary Efficacy of a Live-Chat Social Media Intervention to Reduce HIV Risk Among Young Men Who Have Sex With Men. AIDS Behav. 2015 Jul;19(7):1214–27. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0911-z. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25256808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Noar SM, Black HG, Pierce LB. Efficacy of computer technology-based HIV prevention interventions: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009 Jan 02;23(1):107–15. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831c5500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Swendeman D, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Innovation in sexually transmitted disease and HIV prevention: internet and mobile phone delivery vehicles for global diffusion. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010 Mar;23(2):139–44. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328336656a. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20087189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ellen JM, Greenberg L, Willard N, Korelitz J, Kapogiannis BG, Monte D, Boyer CB, Harper GW, Henry-Reid LM, Friedman LB, Gonin R. Evaluation of the effect of human immunodeficiency virus-related structural interventions: the connect to protect project. JAMA Pediatr. 2015 Mar;169(3):256–63. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3010. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25580593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miller RL, Boyer CB, Chiaramonte D, Lindeman P, Chutuape K, Cooper-Walker B, Kapogiannis BG, Wilson CM, Fortenberry JD. Evaluating Testing Strategies for Identifying Youths With HIV Infection and Linking Youths to Biomedical and Other Prevention Services. JAMA Pediatr. 2017 Jun 01;171(6):532–537. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0105. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28418524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miller RL, Chiaramonte D, Strzyzykowski T, Sharma D, Anderson-Carpenter K, Fortenberry JD. Improving Timely Linkage to Care among Newly Diagnosed HIV-Infected Youth: Results of SMILE. J Urban Health. 2019 Dec 01;96(6):845–855. doi: 10.1007/s11524-019-00391-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.ATN 151 Work-to-Prevent: Employment as HIV Prevention (W2P) ClinicalTrials.gov. [2018-07-19]. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03313310.

- 59.Naar S, Hudgens MG, Brookmeyer R, Idalski Carcone A, Chapman J, Chowdhury S, Ciaranello A, Comulada WS, Ghosh S, Horvath KJ, Ingram L, LeGrand S, Reback CJ, Simpson K, Stanton B, Starks T, Swendeman D. Improving the Youth HIV Prevention and Care Cascades: Innovative Designs in the Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2019 Sep;33(9):388–398. doi: 10.1089/apc.2019.0095. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/31517525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, Flannery D, Rice E, Adamson DM, Ingram B. Common factors in effective HIV prevention programs. AIDS Behav. 2009 Jun;13(3):399–408. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9464-3. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/18830813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chambers DA. Sharpening our focus on designing for dissemination: Lessons from the SPRINT program and potential next steps for the field. Transl Behav Med. 2019 Jul 17; doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibz102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Newman BS, Passidomo K, Gormley K, Manley A. Use of Drop-In Clinic Versus Appointment-Based Care for LGBT Youth: Influences on the Likelihood to Access Different Health-Care Structures. LGBT Health. 2014 Jun;1(2):140–6. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2013.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hadland SE, Yehia BR, Makadon HJ. Caring for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning Youth in Inclusive and Affirmative Environments. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016 Dec;63(6):955–969. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.001. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/27865338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jadwin-Cakmak L, Bauermeister JA, Cutler JM, Loveluck J, Kazaleh Sirdenis T, Fessler KB, Popoff EE, Benton A, Pomerantz NF, Gotts Atkins SL, Springer T, Harper GW. The Health Access Initiative: A Training and Technical Assistance Program to Improve Health Care for Sexual and Gender Minority Youth. J Adolesc Health. 2020 Jul;67(1):115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goldenberg T, Jadwin-Cakmak L, Popoff E, Reisner SL, Campbell BA, Harper GW. Stigma, Gender Affirmation, and Primary Healthcare Use Among Black Transgender Youth. J Adolesc Health. 2019 Oct;65(4):483–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.04.029. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/31303554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hafeez H, Zeshan M, Tahir MA, Jahan N, Naveed S. Health Care Disparities Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth: A Literature Review. Cureus. 2017 Apr 20;9(4):e1184. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1184. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28638747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gridley SJ, Crouch JM, Evans Y, Eng W, Antoon E, Lyapustina M, Schimmel-Bristow A, Woodward J, Dundon K, Schaff R, McCarty C, Ahrens K, Breland DJ. Youth and Caregiver Perspectives on Barriers to Gender-Affirming Health Care for Transgender Youth. J Adolesc Health. 2016 Sep;59(3):254–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mayer KH, Garofalo R, Makadon HJ. Promoting the successful development of sexual and gender minority youths. Am J Public Health. 2014 Jun;104(6):976–81. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.White Hughto JM, Reisner SL, Pachankis JE. Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Soc Sci Med. 2015 Dec;147:222–31. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26599625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cuevas AG, O'Brien K, Saha S. African American experiences in healthcare: "I always feel like I'm getting skipped over". Health Psychol. 2016 Sep;35(9):987–95. doi: 10.1037/hea0000368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Institute of Medicine . Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bauermeister JA, Pingel ES, Sirdenis TK, Andrzejewski J, Gillard G, Harper GW, Michigan Forward in Enhancing ResearchCommunity Equity (MFierce) Coalition Ensuring Community Participation During Program Planning: Lessons Learned During the Development of a HIV/STI Program for Young Sexual and Gender Minorities. Am J Community Psychol. 2017 Sep;60(1-2):215–228. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12147. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28685871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bauermeister JA, Golinkoff JM, Horvath KJ, Hightow-Weidman LB, Sullivan PS, Stephenson R. A Multilevel Tailored Web App-Based Intervention for Linking Young Men Who Have Sex With Men to Quality Care (Get Connected): Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2018 Aug 02;7(8):e10444. doi: 10.2196/10444. https://www.researchprotocols.org/2018/8/e10444/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Smith DK, Mendoza MC, Stryker JE, Rose CE. PrEP Awareness and Attitudes in a National Survey of Primary Care Clinicians in the United States, 2009-2015. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156592. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156592. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0156592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Krakower D, Ware N, Mitty JA, Maloney K, Mayer KH. HIV providers' perceived barriers and facilitators to implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis in care settings: a qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2014 Sep;18(9):1712–21. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0839-3. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24965676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Krakower DS, Ware NC, Maloney KM, Wilson IB, Wong JB, Mayer KH. Differing Experiences with Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis in Boston Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Specialists and Generalists in Primary Care: Implications for Scale-Up. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2017 Jul;31(7):297–304. doi: 10.1089/apc.2017.0031. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28574774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu A, Cohen S, Follansbee S, Cohan D, Weber S, Sachdev D, Buchbinder S. Early experiences implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention in San Francisco. PLoS Med. 2014 Mar;11(3):e1001613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001613. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, Bacon O, Doblecki-Lewis S, Postle BS, Feaster DJ, Matheson T, Trainor N, Blue RW, Estrada Y, Coleman ME, Elion R, Castro JG, Chege W, Philip SS, Buchbinder S, Kolber MA, Liu AY. High interest in preexposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men at risk for HIV infection: baseline data from the US PrEP demonstration project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015 Apr 01;68(4):439–48. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000479. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25501614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Prevent HIV and Other STIs. NYC Government. 2018. [2017-03-14]. http://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/health/health-topics/playsure.page.

- 80.NYC Health Dept. Lauches PrEP, PEP Outreach Campaign. POZ. [2017-03-14]. https://www.poz.com/article/nyc-promotes-prep-26694-2670.

- 81.Learning Resources — Learning Modules. National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center. [2017-03-14]. https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/resources/type/learning-module/

- 82.Introducing the CCC PrEPline! National Clinical Consultation Center. [2017-03-14]. http://nccc.ucsf.edu/2014/09/29/introducing-the-ccc-prepline/

- 83.Saag M, Daskalakis D, Ramers C, Smith D. Preventing HIV Infection in the Primary Care Setting: The Role of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis. Medscape. [2017-06-15]. https://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/867876_sidebar1.

- 84.Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Lassiter JM, Whitfield THF, Starks TJ, Grov C. Uptake of HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) in a National Cohort of Gay and Bisexual Men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017 Mar 01;74(3):285–292. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001251. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28187084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Paltiel AD, Freedberg KA, Scott CA, Schackman BR, Losina E, Wang B, Seage GR, Sloan CE, Sax PE, Walensky RP. HIV preexposure prophylaxis in the United States: impact on lifetime infection risk, clinical outcomes, and cost-effectiveness. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Mar 15;48(6):806–15. doi: 10.1086/597095. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/19193111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Haberer JE, Bangsberg DR, Baeten JM, Curran K, Koechlin F, Amico KR, Anderson P, Mugo N, Venter F, Goicochea P, Caceres C, O'Reilly K. Defining success with HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: a prevention-effective adherence paradigm. AIDS. 2015 Jul 17;29(11):1277–85. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000647. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26103095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Van der Elst EM, Mbogua J, Operario D, Mutua G, Kuo C, Mugo P, Kanungi J, Singh S, Haberer J, Priddy F, Sanders EJ. High acceptability of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis but challenges in adherence and use: qualitative insights from a phase I trial of intermittent and daily PrEP in at-risk populations in Kenya. AIDS Behav. 2013 Jul;17(6):2162–72. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0317-8. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/23080358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Study to Evaluate the Efficacy, Safety, and Tolerability of Long-acting Intramuscular Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine for Maintenance of Virologic Suppression Following Switch From an Integrase Inhibitor in HIV-1 Infected Therapy Naive Participants. ClinicalTrials.gov. [2018-07-19]. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02938520.

- 89.Study Evaluating the Efficacy, Safety, and Tolerability of Switching to Long-acting Cabotegravir Plus Long-acting Rilpivirine From Current Antiretroviral Regimen in Virologically Suppressed HIV-1-infected Adults. ClinicalTrials.gov. [2018-07-19]. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02951052.

- 90.Evaluating the Safety and Efficacy of the VRC01 Antibody in Reducing Acquisition of HIV-1 Infection Among Men and Transgender Persons Who Have Sex With Men. ClinicalTrials.gov. [2018-07-19]. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02716675.

- 91.Kapogiannis BG, Handelsman E, Ruiz MS, Lee S. Introduction: Paving the way for biomedical HIV prevention interventions in youth. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010 Jul;54 Suppl 1:S1–4. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e2cf8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gilbert AL, Knopf AS, Fortenberry JD, Hosek SG, Kapogiannis BG, Zimet GD. Adolescent Self-Consent for Biomedical Human Immunodeficiency Virus Prevention Research. J Adolesc Health. 2015 Jul;57(1):113–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.03.017. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26095412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rerks-Ngarm S, Pitisuttithum P, Nitayaphan S, Kaewkungwal J, Chiu J, Paris R, Premsri N, Namwat C, de Souza M, Adams E, Benenson M, Gurunathan S, Tartaglia J, McNeil JG, Francis DP, Stablein D, Birx DL, Chunsuttiwat S, Khamboonruang C, Thongcharoen P, Robb ML, Michael NL, Kunasol P, Kim JH, MOPH-TAVEG Investigators Vaccination with ALVAC and AIDSVAX to prevent HIV-1 infection in Thailand. N Engl J Med. 2009 Dec 03;361(23):2209–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bar KJ, Sneller MC, Harrison LJ, Justement JS, Overton ET, Petrone ME, Salantes DB, Seamon CA, Scheinfeld B, Kwan RW, Learn GH, Proschan MA, Kreider EF, Blazkova J, Bardsley M, Refsland EW, Messer M, Clarridge KE, Tustin NB, Madden PJ, Oden K, O'Dell SJ, Jarocki B, Shiakolas AR, Tressler RL, Doria-Rose NA, Bailer RT, Ledgerwood JE, Capparelli EV, Lynch RM, Graham BS, Moir S, Koup RA, Mascola JR, Hoxie JA, Fauci AS, Tebas P, Chun T. Effect of HIV Antibody VRC01 on Viral Rebound after Treatment Interruption. N Engl J Med. 2016 Nov 24;375(21):2037–2050. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1608243. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/27959728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Caskey M, Schoofs T, Gruell H, Settler A, Karagounis T, Kreider EF, Murrell B, Pfeifer N, Nogueira L, Oliveira TY, Learn GH, Cohen YZ, Lehmann C, Gillor D, Shimeliovich I, Unson-O'Brien C, Weiland D, Robles A, Kümmerle T, Wyen C, Levin R, Witmer-Pack M, Eren K, Ignacio C, Kiss S, West AP, Mouquet H, Zingman BS, Gulick RM, Keler T, Bjorkman PJ, Seaman MS, Hahn BH, Fätkenheuer G, Schlesinger SJ, Nussenzweig MC, Klein F. Antibody 10-1074 suppresses viremia in HIV-1-infected individuals. Nat Med. 2017 Feb;23(2):185–191. doi: 10.1038/nm.4268. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28092665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Frohlich JA, Grobler AC, Baxter C, Mansoor LE, Kharsany AB, Sibeko S, Mlisana KP, Omar Z, Gengiah TN, Maarschalk S, Arulappan N, Mlotshwa M, Morris L, Taylor D, CAPRISA 004 Trial Group Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science. 2010 Sep 03;329(5996):1168–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=20643915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Baeten JM, Palanee-Phillips T, Brown ER, Schwartz K, Soto-Torres LE, Govender V, Mgodi NM, Matovu Kiweewa F, Nair G, Mhlanga F, Siva S, Bekker L, Jeenarain N, Gaffoor Z, Martinson F, Makanani B, Pather A, Naidoo L, Husnik M, Richardson BA, Parikh UM, Mellors JW, Marzinke MA, Hendrix CW, van der Straten A, Ramjee G, Chirenje ZM, Nakabiito C, Taha TE, Jones J, Mayo A, Scheckter R, Berthiaume J, Livant E, Jacobson C, Ndase P, White R, Patterson K, Germuga D, Galaska B, Bunge K, Singh D, Szydlo DW, Montgomery ET, Mensch BS, Torjesen K, Grossman CI, Chakhtoura N, Nel A, Rosenberg Z, McGowan I, Hillier S, MTN-020–ASPIRE Study Team Use of a Vaginal Ring Containing Dapivirine for HIV-1 Prevention in Women. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 01;375(22):2121–2132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506110. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26900902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Luzuriaga K, Gay H, Ziemniak C, Sanborn KB, Somasundaran M, Rainwater-Lovett K, Mellors JW, Rosenbloom D, Persaud D. Viremic relapse after HIV-1 remission in a perinatally infected child. N Engl J Med. 2015 Feb 19;372(8):786–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1413931. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25693029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Deeks SG, Lewin SR, Ross AL, Ananworanich J, Benkirane M, Cannon P, Chomont N, Douek D, Lifson JD, Lo Y, Kuritzkes D, Margolis D, Mellors J, Persaud D, Tucker JD, Barre-Sinoussi F, International AIDS Society Towards a Cure Working Group. Alter G, Auerbach J, Autran B, Barouch DH, Behrens G, Cavazzana M, Chen Z, Cohen A, Corbelli GM, Eholié S, Eyal N, Fidler S, Garcia L, Grossman C, Henderson G, Henrich TJ, Jefferys R, Kiem H, McCune J, Moodley K, Newman PA, Nijhuis M, Nsubuga MS, Ott M, Palmer S, Richman D, Saez-Cirion A, Sharp M, Siliciano J, Silvestri G, Singh J, Spire B, Taylor J, Tolstrup M, Valente S, van Lunzen J, Walensky R, Wilson I, Zack J. International AIDS Society global scientific strategy: towards an HIV cure 2016. Nat Med. 2016 Aug;22(8):839–50. doi: 10.1038/nm.4108. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/27400264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Galvin SR, Cohen MS. The role of sexually transmitted diseases in HIV transmission. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004 Jan;2(1):33–42. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hütter G, Nowak D, Mossner M, Ganepola S, Müssig A, Allers K, Schneider T, Hofmann J, Kücherer C, Blau O, Blau IW, Hofmann WK, Thiel E. Long-term control of HIV by CCR5 Delta32/Delta32 stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2009 Feb 12;360(7):692–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Muessig KE, Nekkanti M, Bauermeister J, Bull S, Hightow-Weidman LB. A systematic review of recent smartphone, Internet and Web 2.0 interventions to address the HIV continuum of care. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015 Mar;12(1):173–90. doi: 10.1007/s11904-014-0239-3. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25626718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Holloway IW, Rice E, Gibbs J, Winetrobe H, Dunlap S, Rhoades H. Acceptability of smartphone application-based HIV prevention among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2014 Feb;18(2):285–96. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0671-1. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24292281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rice E, Tulbert E, Cederbaum J, Barman Adhikari A, Milburn NG. Mobilizing homeless youth for HIV prevention: a social network analysis of the acceptability of a face-to-face and online social networking intervention. Health Educ Res. 2012 Apr;27(2):226–36. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr113. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22247453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Thirumurthy H, Lester RT. M-health for health behaviour change in resource-limited settings: applications to HIV care and beyond. Bull World Health Organ. 2012 May 01;90(5):390–2. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.099317. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22589574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hightow-Weidman LB, Muessig KE, Bauermeister J, Zhang C, LeGrand S. Youth, Technology, and HIV: Recent Advances and Future Directions. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015 Dec;12(4):500–15. doi: 10.1007/s11904-015-0280-x. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26385582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.LeGrand S, Knudtson K, Benkeser D, Muessig K, Mcgee A, Sullivan PS, Hightow-Weidman L. Testing the Efficacy of a Social Networking Gamification App to Improve Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Adherence (P3: Prepared, Protected, emPowered): Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2018 Dec 18;7(12):e10448. doi: 10.2196/10448. http://www.researchprotocols.org/2018/12/e10448/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Berlan ED, Bravender T. Confidentiality, consent, and caring for the adolescent patient. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009 Aug;21(4):450–6. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32832ce009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Harper GW, Riplinger AJ. HIV prevention interventions for adolescents and young adults: what about the needs of gay and bisexual males? AIDS Behav. 2013 Mar;17(3):1082–95. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rasberry CN, Condron DS, Lesesne CA, Adkins SH, Sheremenko G, Kroupa E. Associations Between Sexual Risk-Related Behaviors and School-Based Education on HIV and Condom Use for Adolescent Sexual Minority Males and Their Non-Sexual-Minority Peers. LGBT Health. 2018 Jan;5(1):69–77. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2017.0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mirzazadeh A, Biggs MA, Viitanen A, Horvath H, Wang LY, Dunville R, Barrios LC, Kahn JG, Marseille E. Do School-Based Programs Prevent HIV and Other Sexually Transmitted Infections in Adolescents? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Prev Sci. 2018 May 8;19(4):490–506. doi: 10.1007/s11121-017-0830-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hatzenbuehler ML. The Influence of State Laws on the Mental Health of Sexual Minority Youth. JAMA Pediatr. 2017 Apr 01;171(4):322–324. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.4732. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28241255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Coulter RW, Birkett M, Corliss HL, Hatzenbuehler ML, Mustanski B, Stall RD. Associations between LGBTQ-affirmative school climate and adolescent drinking behaviors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016 Apr 01;161:340–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.02.022. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26946989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Neilan A, Bangs A, Hudgens M, Patel K, Agwu A, Gaur A. Can Adherence Interventions be Cost-Effective Among Youth with HIV?. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); March 8-11, 2020; Boston, Massachusetts. 2020. Mar 08, [Google Scholar]

- 115.Neilan AM, Patel K, Agwu AL, Bassett IV, Amico KR, Crespi CM, Gaur AH, Horvath KJ, Powers KA, Rendina HJ, Hightow-Weidman LB, Li X, Naar S, Nachman S, Parsons JT, Simpson KN, Stanton BF, Freedberg KA, Bangs AC, Hudgens MG, Ciaranello AL. Model-Based Methods to Translate Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions Findings Into Policy Recommendations: Rationale and Protocol for a Modeling Core (ATN 161) JMIR Res Protoc. 2019 Apr 16;8(4):e9898. doi: 10.2196/resprot.9898. https://www.researchprotocols.org/2019/4/e9898/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]