Abstract

Cytosolic 5′-nucleotidases II (cNT5-II) are an evolutionary conserved family of 5′-nucleotidases that catalyze the intracellular hydrolysis of nucleotides. In humans, the family is encoded by five genes, namely NT5C2, NT5DC1, NT5DC2, NT5DC3, and NT5DC4. While very little is known about the role of these genes in the nervous system, several of them have been associated with neuropsychiatric disorders. Here, we tested whether manipulating neuronal expression of cNT5-II orthologues affects neuropsychiatric disorders-related phenotypes in the model organism Drosophila melanogaster. We investigated the brain expression of Drosophila orthologues of cNT5-II family (dNT5A-CG2277, dNT5B-CG32549, and dNT5C-CG1814) using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Using the UAS/Gal4 system, we also manipulated the expression of these genes specifically in neurons. The knockdown was subjected to neuropsychiatric disorder-relevant behavioral assays, namely light-off jump reflex habituation and locomotor activity, and sleep was measured. In addition, neuromuscular junction synaptic morphology was assessed. We found that dNT5A, dNT5B, and dNT5C were all expressed in the brain. dNT5C was particularly enriched in the brain, especially at pharate and adult stages. Pan-neuronal knockdown of dNT5A and dNT5C showed impaired habituation learning. Knockdown of each of the genes also consistently led to mildly reduced activity and/or increased sleep. None of the knockdown models displayed significant alterations in synaptic morphology. In conclusion, in addition to genetic associations with psychiatric disorders in humans, altered expression of cNT5-II genes in the Drosophila nervous system plays a role in disease-relevant behaviors.

Subject terms: Molecular neuroscience, ADHD, Schizophrenia

Introduction

The family of cytosolic 5′-nucleotidase II (cNT5-II) consists of five highly conserved enzymes, encoded by the NT5C2, NT5DC1, NT5DC2, NT5DC3, and NT5DC4 genes. Research so far has mainly concentrated on NT5C2, which catalyzes the dephosphorylation of purine nucleotides into corresponding purine nucleosides. The enzyme has a high affinity for 5′-inosine monophosphate (IMP) and 5′-guanosine monophosphate (GMP) and is likely to play a role in regulating cellular IMP and GMP levels1. NT5C2 has also been shown to negatively regulate phosphorylation of the alpha subunit of 5′-adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK alpha) and protein translation2,3. No research has yet addressed the 5′-nucleotidase activity of other family members; however, domain similarity infers conserved catalytic activity.

Dysfunction of members of the cNT5-II family has been linked to immunological disorders, sensitivity to cancer treatment, and to metabolic disorders4. Additionally, associations with neurological and psychiatric disorders have been reported (Supplementary Table 1A–E). Truncation and aberrant splicing of NT5C2 causes a form of spastic paraplegia (SPG45), which is frequently accompanied by intellectual disability (ID), a thin corpus callosum, and symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)5–8. Neuronal expression of Drosophila NT5C2 orthologue has also been shown to be essential for locomotor performance2. Associations of NT5C2 have additionally been seen with cognitive abilities as well as schizophrenia in several genome-wide association studies (GWASs)9 (Supplementary Table 1A). The schizophrenia risk variants rs11191419 and ch10_104957618_I were associated with reduced NT5C2 expression in the fetal and adult brain10. Furthermore, a locus containing NT5C2 was genome-wide significantly associated with insomnia in a recent GWAS11. Another family member, NT5DC2, has also repeatedly been associated with cognitive performance, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder9 (Supplementary Table 1C). It was shown that NT5DC2 can competitively inhibit monoamine synthesis by inhibiting tyrosine hydroxylase12. Suggestive associations with ADHD and bipolar disorder have also been noted for NT5DC1 in genetic association studies13,14, and the expression level of Nt5dc3 in a mouse model has been positively correlated with reversal learning performance15. No links with brain function have been reported for NT5DC4 so far.

Little is yet known about how the cNT5-II enzymes affect the brain and nervous system. Animal models provide excellent opportunities to deepen our understanding of this highly conserved gene family. The fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster is a well-established, cost-efficient and time-efficient model to investigate human traits and diseases, both somatic and brain-based. Despite the evolutionary distance between flies and humans, a strong conservation of genes and regulatory networks exists (e.g., see refs. 16,17), and nearly 75% of disease-related human genes have functional Drosophila orthologs18,19. Genetic manipulation is fast and easy, e.g., through the UAS/Gal4 system, which allows manipulation of gene expression specifically in desired tissues or cell populations, such as neurons20. We have previously shown that manipulation of ADHD genes in Drosophila caused altered locomotor activity and reduced sleep21,22. Additionally, in a large-scale screen of Drosophila models of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders, we demonstrated that deficits in habituation learning, a simple form of learning that serves as a cognitive filter, were highly abundant23. Altered habituation has been reported in, for example, Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), ADHD and schizophrenia24. Here, we studied the expression of cNT5-II genes, i.e., CG1814, CG2277, and CG32549 (Supplementary Fig. 1), in the nervous system of Drosophila across the lifespan and investigated effects of neuronal knockdown of the Drosophila orthologues on neuropsychiatric disorder-relevant phenotypes of locomotor activity, sleep, habituation, as well as on synapse morphology.

Materials and methods

Fly stocks

Flies were maintained and crossed on standard corn meal medium at 28 °C, 60% relative humidity, unless specified. The following inducible UAS-RNAi Drosophila lines were obtained from the Vienna Drosophila Resource Center (VDRC), RNAi1–v19096 (w1118;; P[GD8619]v19096) and RNAi2–v106195 (P[KK102549]VIE-260B/CyO) to knockdown CG1814 (termed dNT5C); RNAi1–v20869 (w1118;; P[GD9772]v20869) and RNAi2–v108903 (P[KK105724]VIE-260B) to knockdown CG2277 (termed dNT5A); RNAi1–v30079 (w1118;; P[GD14594]v30079) and RNAi2–v103916 (P[KK101772]VIE-260B) to knockdown CG32549 (termed dNT5B)25. The v60000 line served as genetic background control for RNAi1 and v60100 for RNAi2. Validation experiments of the RNAi lines are available in Supplementary Fig. 2. The v110662 line (P[KK100579]VIE-260B), contains insertion at both 30B and 40D landing sites, and v60101, containing a UAS sequence at the 40D landing site, served as positive controls for diagnostic PCR determining the landing site. For expression level analysis, wild type flies derived from Canton S and Oregon R strains were used. The following drivers were used to induce knockdown ubiquitously (w*;; da.G32-Gal4) or pan-neuronally (yw* UAS-Dcr2 hs(X);; nSyb-Gal4). UAS-Dcr2 was used to increase the efficiency of the knockdown25. For the habituation assay, two copies of GMR-wIR element were included in the driver line to suppress the eye color in the progeny, which is required for the light-off jump reflex (LOJR) to occur (w-; 2xGMR-wIR; nSyb-Gal4, UAS-Dcr2)26.

RNA extraction and quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR)

To determine Drosophila cNT5-II (dNT5) genes expression in the brain, ten male animals of each indicated developmental stage were collected, washed from excess food and dissected in ice-cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to dissect the brains from the rest of the body. Both tissue fractions were submerged in RNAlater (Sigma, Germany) and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. The investigated developmental stage were chosen based on the ones represented in data resources such as FlyAtlas and modENCODE27,28. The total RNA was then isolated with Arcturus Picopure (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Lithuania) and measured with Qubit HS RNA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Lithuania) or Nanodrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from total RNA with iScript kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA). The cDNA was diluted 10× and subjected to qRT-PCR using Power SYBR® Green PCR master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, UK) with 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) in 384-well plate format (primer sequences available in Supplementary Table 2). Primer sets were designed with Primer329, unless specified. eIF-1A and αTub84B were used as internal control. Cycle threshold (CT) values were determined with SDS 2.4 (Applied Biosystems) and the difference of expression level was determined using ΔΔCT method30. Significance was calculated using paired T-test with Prism 5.03 (Graphpad Software, San Diego, CA).

Neuromuscular junction visualization and quantification

Neuromuscular junction visualization and quantification were performed as described by Nijhof et al. and Castels-Nobau et al.31,32. In brief, third instar wandering male larvae were dissected according to the open book preparation method and preserved in 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. The larvae were incubated overnight at 4 °C with mouse anti-nc82 (1:125) (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), followed by 2 h incubation at room temperature with Alexa 488 goat-anti-mouse (1:125) (Invitrogen Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) to visualize active zones. To visualize the postsynaptic morphology of the motor neuron terminals, specimen were further incubated for 1.5 h at room temperature with anti-Dlg-1 antibody (1:25) (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) that had previously been conjugated with the Zenon Alexa Fluor 568 Mouse IgG1 labeling kit (Invitrogen, CA, USA). The immunolabeled larvae were mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and imaged with a Zeiss Axio Imager microscope at 630x magnification using 63× oil immersion objective lens with ApoTome.2 (Zeiss). Images were analyzed with the Drosophila NMJ morphometrics macro31,32 in FIJI 1.49k33 to obtain eight interdependent morphology-related parameters (area, perimeter, length, longest branch length, bouton count, branch point, branch number, and island) and number of active zone. For each genotype, synapses from 5 to 10 animals were analyzed. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s post-hoc test against appropriate genetic background controls was performed with Prism 5.03 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) to obtain an adjusted p-value (padj).

Behavioral assays

Habituation

The habituation assay was performed as previously described23. Flies were grown and maintained at 25 °C, 70% humidity for habituation experiments. Male flies were collected with CO2, allowed to recover for at least 48 h and tested in the light-off jump reflex system (Aktogen, Hungary) at 3–7 days post-eclosion. Individually housed flies received 100 light-off pulses for 15 ms with 1 s interpulse interval. The frequency of wing vibration following a jump response was measured at each trial and a threshold was applied to filter out background noise. Data were collected and analyzed in a custom made Labview Software (National Instruments). Only genotypes with >50% of flies that jump at least once within the first five trials (n jumpers) were analyzed. The total number of tested flies (n total) and the number of flies jumping on the first five trials (n jumpers) are provided in Supplementary Table 3. Habituation was quantified using the trials-to-criterion (TTC), which corresponds to the number of the trial at which a fly stops jumping for at least five consecutive trials. General linear model regression analysis with correction according to the number of RNAi lines tested was performed on the log-TTC values using R statistical software to obtain an adjusted p-value (padj).

Activity and sleep monitoring

Activity and sleep monitoring were performed as described by van der Voet et al. and Klein et al.21,22. Male flies age 3–5 days were collected with CO2 and allowed to recover for at least 24 h. The flies were then monitored using Drosophila activity monitoring (DAM) system (Trikinetics, Waltham, MA, USA) at 28 °C 60% relative humidity for 4 days in 12:12-h light:dark scheme. Activity counts were collected in 30-s bins. Activity and sleep analysis were performed with Sleep and Circadian Analysis MATLAB Program (SCAMP)34; sleep was defined as a minimum of 5 min of inactivity35. Both activity and sleep were averaged over 4 days and plotted in 30-min bins. Day was defined as the interval between zeitgeber (ZT) 0–12 h and night as ZT 12–24 h. Day and night total activity, total sleep, activity while awake, sleep latency, sleep bout, and sleep bout duration were averaged over 4 days and were separately tested with one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test against their respective genetic background controls in Prism 5.03 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) to obtain final p-value (padj).

Results

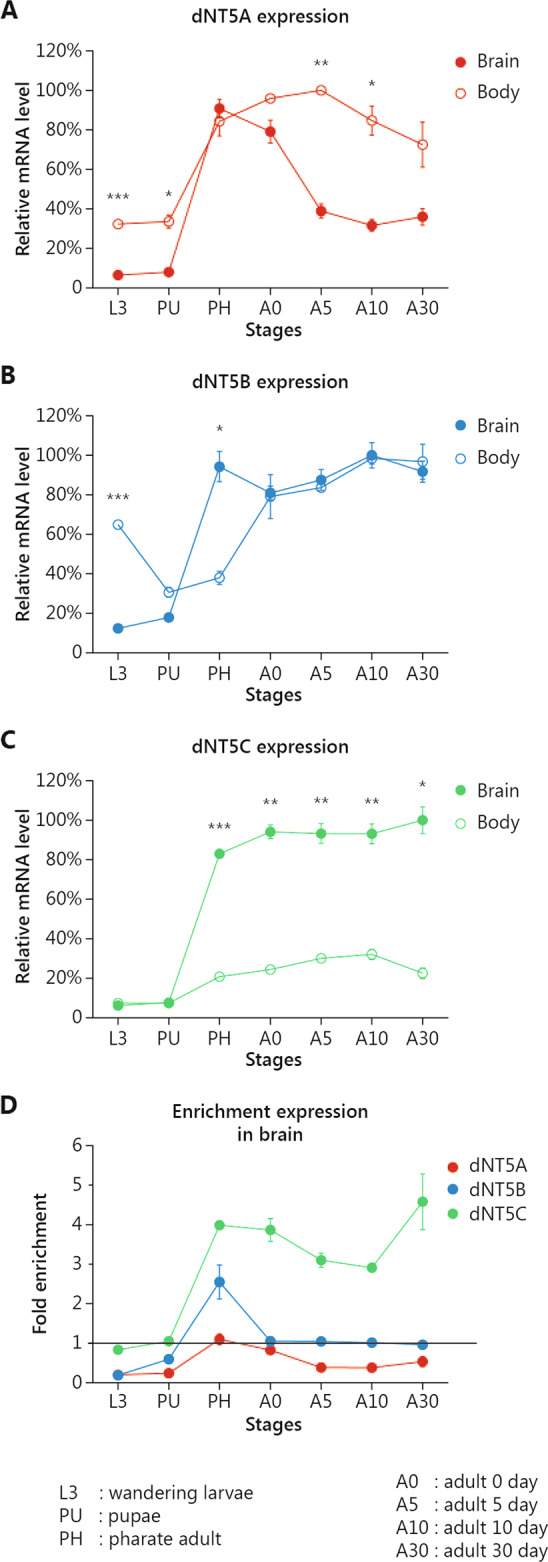

Expression of cNT5-II genes in the Drosophila central nervous system across lifespan

We investigated the following cNT5-II gene orthologues in Drosophila: dNT5A (CG2277, ortholog of NT5DC1), dNT5B (CG32549, ortholog of NT5C2 and NTDC4), and dNT5C (CG1814, ortholog of NT5DC2 and NT5DC3). The phylogenetic relationships between these genes are visualized in Supplementary Fig. 1. Investigating the expression of the Drosophila cNT5-II (dNT5) genes using qRT-PCR analysis to determine expression levels of each gene in the brain relative to the rest of the body across developmental stages, we found all three genes to be expressed in the brain (Fig. 1A–C). Expression of the genes was low at L3 larval (L3) and early pupal (PU) stages and increased from late pupal/pharate (PH) stage onwards. Expression of dNT5A was consistently lower in the brain than in the rest of the body, except for the PH stage (Fig. 1A, D). Also, dNT5B expression was initially higher in the rest of the body than in the brain at L3 and PU stages, but at the PH stage, brain expression increased up to 5-fold and remained similar to the expression in the body throughout adult stages (A0–A30) (Fig. 1B, D). Expression of dNT5C was initially similar in the brain and the rest of the body, but with onset at from the PH stage, brain expression became highly enriched and remained so throughout adult stages (Fig. 1C, D). Absolute expression levels, and thereby also absolute differences between expression of the three paralogous genes cannot be deduced from qRT-PCR data.

Fig. 1. dNT5 genes are expressed in the Drosophila brain, where dNT5C shows the highest enrichment compared to dNT5A and dNT5B.

A–C mRNA levels of A dNT5A, B dNT5B, and C dNT5C in brain (filled circles) and rest of the body (empty circles) at different developmental stages, quantified by qRT-PCR relative to the maximum value detected among the assessed stages (100%). D Enrichment of expression levels in the brain compared to the body for each individual dNT5 gene. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. Paired T-test was performed to obtain a p-value. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). N = 3 biological replicates/stage, ten animals/replicate.

Altered expression of dNT5 genes in RNAi-mediated knockdown

We validated available RNAi lines targeting each member of the dNT5 family. All RNAi constructs are predicted to be highly specific, with <0.5% predicted off-target 19-mers (s19 score >0.99, obtained from VDRC website, www.vdrc.at). First, we performed diagnostic PCR to map the integration site of UAS-RNAi2, as constructs from the VDRC KK collection might be inserted in chromosome 2 at either 30B and/or 40D locus. dNT5A RNAi2 and dNT5C RNAi2 constructs were integrated only at the 30B locus, and dNT5B RNAi2 was inserted at the 40D locus. As insertions at the 40D locus can be associated with off-target effects, we did not pursue characterizing dNT5B RNAi2. We proceeded to determine knockdown efficacy of the remaining RNAi lines. Ubiquitous knockdown with dNT5A RNAi1 and RNAi2 reduced dNT5A mRNA level to 20 and 85% of the genetic background control in adulthood, respectively, as determined by using two independent primer pairs (Supplementary Fig. 2B, C). Knockdown of dNT5A with RNAi1 did not alter dNT5B and dNT5C levels; knockdown with RNAi2 slightly lowered also dNT5C level, although this finding did not withstand correction for multiple testing (Supplementary Fig. 2B, C). Ubiquitous knockdown using the remaining dNT5B RNAi line reduced dNT5B level to 40% of the genetic background control in adulthood (Supplementary Fig. 2D). This knockdown did not affect dNT5A or dNT5C levels (Supplementary Fig. 2D). Ubiquitous knockdown with dNT5C RNAi1 and RNAi2 reduced dNT5C levels to 35 and 25% of the genetic background control in adulthood, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2E, F). Knockdown of dNT5C with RNAi1 did not alter dNT5A or dNT5B levels (Supplementary Fig. 2E). Knockdown with RNAi2 showed a slight reduction of dNT5A, but only detected with one primer pair (Supplementary Fig. 2F).

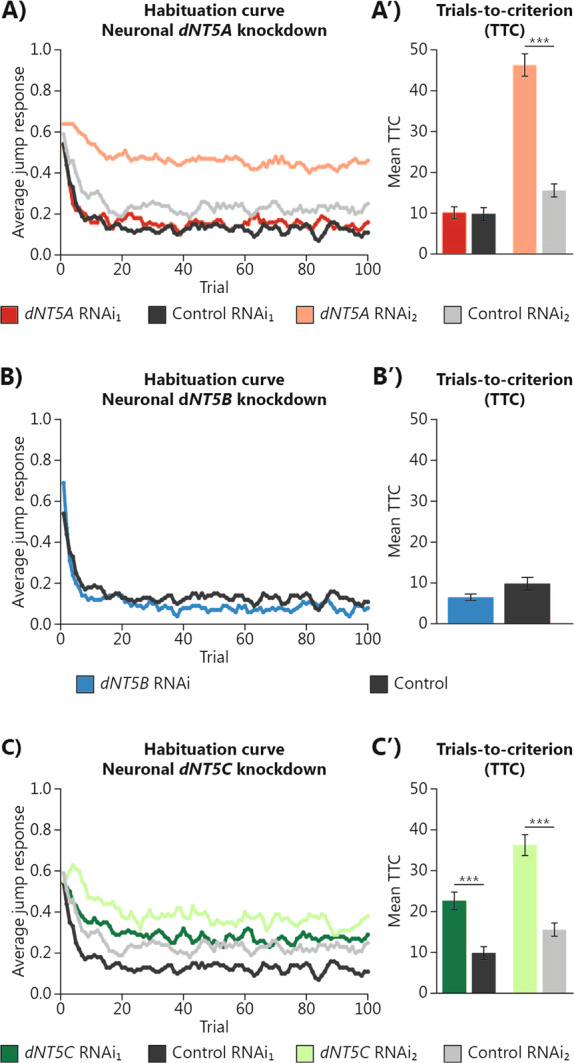

Characterization of dNT5 models in neuropsychiatric disorders-related behaviors

Because of their association with neuropsychiatric disorders in humans, we further asked whether manipulating the expression of Drosophila dNT5 genes in neurons would impact neuropsychiatric disorders-relevant behaviors. We first tested dNT5 models in the light-off jump habituation paradigm, where the flies showed strong initial jumping reaction to non-threatening stimuli (light-off) which gradually weakened due to habituation learning23,26. Habituation is quantified as TTC, the number of stimuli needed to reach habituation criterion (see “Methods” section). Pan-neuronal dNT5A knockdown with RNAi1 showed a TTC similar to the one observed in the genetic background control (padj > 0.05) (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Table 3), while use of RNAi2, caused severe habituation deficits with a 3-fold increased TTC value compared to its control (padj < 0.001) (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Table 3). Pan-neuronal dNT5B knockdown did not affect habituation (padj > 0.05) (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Table 3). Pan-neuronal dNT5C knockdown caused habituation deficits with both RNAi lines (Fig. 2C), with both knockdown models showing more than a 2-fold increase of the TTC value (RNAi1 padj < 0.001; RNAi2 padj < 0.001) (Fig. 2C’ and Supplementary Table 3).

Fig. 2. Neuronal manipulation of dNT5A and dNT5C expression causes habituation deficits.

A–C Average jumping response of A dNT5A, B dNT5B, and C dNT5C pan-neuronal RNAi induction upon 100 consecutive light-off stimuli. A′, B′, C′ Quantification of trials-to-criterion (TTC). A Pan-neuronally induced dNT5A RNAi2 (w; 2xGMR-wIR/UAS-dNT5A RNAi2; nSyb-Gal4, UAS-Dcr2, n = 176) habituated slower than the RNAi2 control (w; 2xGMR-wIR/+; nSyb-Gal4, UAS-Dcr2, n = 123), while RNAi1 (w; 2xGMR-wIR; nSyb-Gal4, UAS-Dcr2/UAS-dNT5A RNAi1, n = 122) habituated similarly to its control (w; 2xGMR-wIR; nSyb-Gal4, UAS-Dcr2/+, n = 112). B Pan-neuronally induced dNT5B RNAi (w; 2xGMR-wIR; nSyb-Gal4, UAS-Dcr2/UAS-dNT5B RNAi, n = 97) habituated similarly to control (w; 2xGMR-wIR; nSyb-Gal4, UAS-Dcr2/+, n = 112). C Pan-neuronally induced dNT5C RNAi1 (w; 2xGMR-wIR; nSyb-Gal4, UAS-Dcr2/UAS-dNT5C RNAi1, n = 161) and RNAi2 (w; 2xGMR-wIR/UAS-dNT5C RNAi2; nSyb-Gal4, UAS-Dcr2, n = 138) habituated slower than their respective controls (RNAi1: w; 2xGMR-wIR; nSyb-Gal4, UAS-Dcr2/+, n = 112; RNAi2: w; 2xGMR-wIR/+; nSyb-Gal4, UAS-Dcr2, n = 123). All genotypes were tested together. Genetic background controls for dNT5A, dNT5B, and dNT5C RNAi1 as well as for dNT5A and dNT5C RNAi2 are identical, respectively, and re-plotted across panels for convenience. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. General linear model regression analysis with correction according the the number of RNAi tested was performed on the log-TTC values to obtain an adjusted p-value (padj). (*padj < 0.05, **padj < 0.01, ***padj < 0.001). N = 3 biological replicates, minimum 30 flies/replicate.

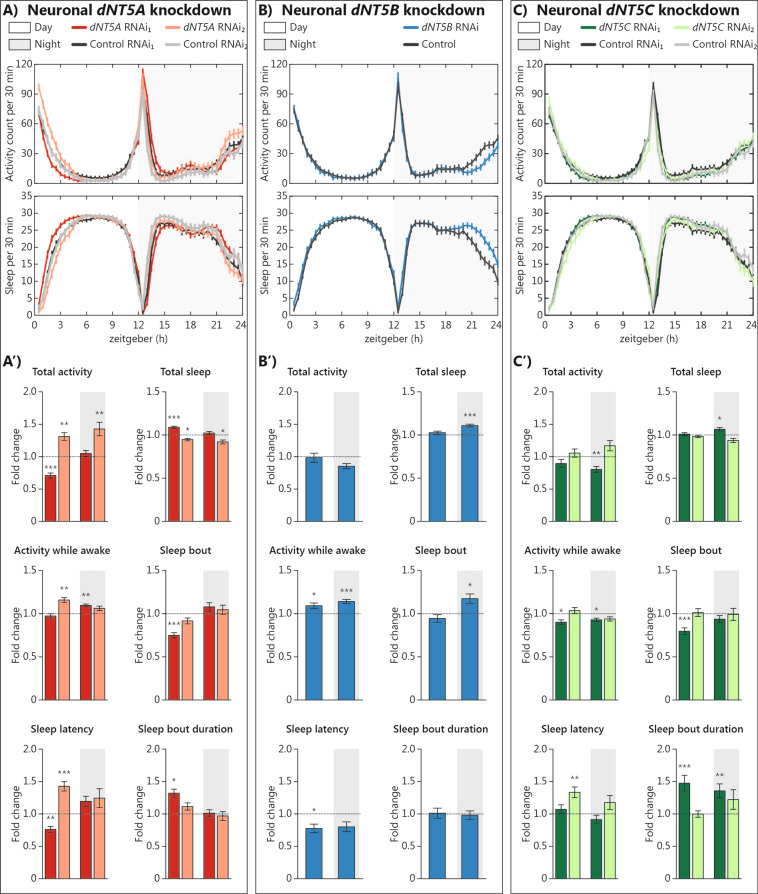

Increased locomotor activity and reduced sleep have been previously shown to characterize Drosophila models of ADHD21,22. Furthermore, increased sleep in male flies has been reported in a Drosophila model of schizophrenia36. When monitoring activity and sleep of dNT5 genes knockdown, we found slight activity and sleep differences compared to controls (Fig. 3A–C). Pan-neuronal dNT5A knockdown with RNAi1 caused 30% less activity counts (padj < 0.001) and 10% increased sleep (padj < 0.001) during the day (Fig. 3A′ and Supplementary Table 4A). Conversely, knockdown with RNAi2 increased activity counts by 30% (padj < 0.01) and reduced sleep by 5% (padj < 0.05) during the day; during the night, the RNAi2 construct increased activity counts by 40% (padj < 0.01) and reduced sleep by 10% (padj < 0.05) (Fig. 3A′ and Supplementary Table 4B). Pan-neuronal dNT5B knockdown showed 10% increased total night sleep (padj < 0.001) (Fig. 3B′ and Supplementary Table 4A). Pan-neuronal dNT5C knockdown with RNAi1 showed 20% reduced total night activity (padj < 0.01) and 5% increased night sleep (padj < 0.05) (Fig. 3C′ and Supplementary Table 4A), but knockdown with RNAi2 showed similar total activity and sleep to the control (Fig. 3C′ and Supplementary Table 4B). Altogether, manipulation of the different dNT5s did affect activity and sleep, with knockdown consistently leading to reduced activity and/or increased sleep, but always in a relatively mild fashion.

Fig. 3. Neuronal manipulation dNT5A, dNT5B, and dNT5C only slightly affected activity and sleep.

A–C Activity and sleep plot of pan-neural manipulation of A dNT5A (RNAi1: w, UAS-Dcr2;; nSyb-Gal4/UAS-dNT5A RNAi1, n = 84; RNAi2: w, UAS-Dcr2; UAS-dNT5A RNAi2; nSyb-Gal4, n = 77), B dNT5B (w, UAS-Dcr2;; nSyb-Gal4/UAS-dNT5B RNAi, n = 71), and C dNT5C (RNAi1: w, UAS-Dcr2;; nSyb-Gal4/UAS-dNT5C RNAi1, n = 86; RNAi2: w, UAS-Dcr2; UAS-dNT5C RNAi2; nSyb-Gal4, n = 61). All genotypes were tested together. Genetic background controls for dNT5A, dNT5B, and dNT5C RNAi1 as well as for dNT5A and dNT5C RNAi2 are identical, respectively, and re-plotted across panels for convenience. A′, B′, C′ Quantification of activity and sleep parameters, normalized to respective control (RNAi1: w, UAS-Dcr2;; nSyb-Gal4/+, n = 88; RNAi2: w, UAS-Dcr2; +; nSyb-Gal4, n = 62). Error bars represent standard error of the mean. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test was used to obtain an adjusted p-value (padj) (*padj < 0.05, **padj < 0.01, ***padj < 0.001). N = 3 biological replicates, minimum 20 flies/replicate.

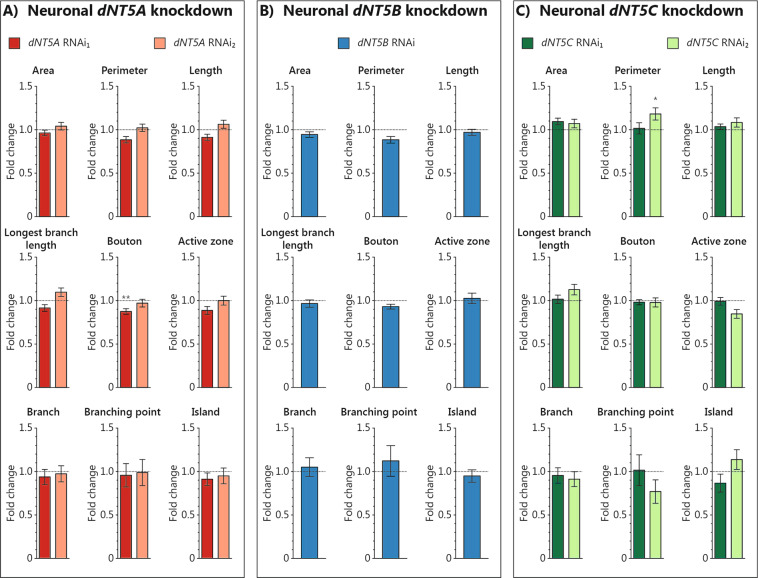

Characterization of synapse morphology in dNT5 models

In addition to the behavioral assays, we also examined synaptic morphology in the dNT5 neuronal knockdown models. Disruption of synaptic development and function has been implicated in multiple psychiatric disorders37–39. For example, the schizophrenia risk gene DISC1 has been shown to regulate synaptogenesis at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction (NMJ)40, a popular model synapse in the fruit fly41,42. In a comprehensive assessment of eight interdependent morphological parameters and the number of active zones, synaptic terminals in the dNT5 models developed largely comparable to their controls (Fig. 4A–C and Supplementary Fig. 3). Pan-neuronal dNT5A knockdown with RNAi1 showed 12% less synaptic boutons than control animals (padj < 0.01) (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Table 5A, B), while pan-neuronal dNT5C knockdown with RNAi2 showed 18% larger perimeter than its control (padj < 0.05) (Fig. 2C and Supplementary Table 5A, B). The dNT5 proteins thus appear to only have very minor, if any, effect on NMJ development and morphology.

Fig. 4. Neuronal manipulation of dNT5A, dNT5B, and dNT5C did not affect development of synaptic terminals at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction (NMJ).

A–C Synaptic NMJ parameters of pan-neuronal manipulation of A dNT5A (RNAi1: w, UAS-Dcr2;; nSyb-Gal4/UAS-dNT5A RNAi1, n = 34; RNAi2: w, UAS-Dcr2; UAS-dNT5A RNAi2; nSyb-Gal4, n = 33), B dNT5B (w, UAS-Dcr2;; nSyb-Gal4/UAS-dNT5B RNAi, n = 29), and C dNT5C (RNAi1: w, UAS-Dcr2;; nSyb-Gal4/UAS-dNT5C RNAi1, n = 15; RNAi2: w, UAS-Dcr2; UAS-dNT5C RNAi2; nSyb-Gal4, n = 26). All values were normalized to respective control (dNT5A, dNT5B, and dNT5C RNAi1: w, UAS-Dcr2;; nSyb-Gal4/+, n = 36; dNT5A and dNT5C RNAi2: w, UAS-Dcr2; +; nSyb-Gal4, n = 40). Representative NMJ terminal microscope images are presented in Supplementary Fig. 3. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test was used to obtain an adjusted p-value (padj). (*padj < 0.05, **padj < 0.01, ***padj < 0.001). N = 5–10 animals/genotype.

Discussion

Despite multiple associations to neuropsychiatric disorders, the role of the cytosolic 5′-nucleotidase II (cNT5-II) family of enzymes in nervous system functioning is still largely unknown. Prior to the current study, among the cNT5-II family members, a neuronal function had only been demonstrated for NT5C2; the neuronal function of NT5DC1, NT5DC2, NT5DC3, and NT5DC4 was yet to be investigated. Here, we investigated the neuronal expression and function of NT5C2, NT5DC1, NT5DC2, NT5DC3, and NT5DC4 orthologous genes in Drosophila. Our data showed that the cNT5-II (dNT5) genes are expressed in the brain and that altering their neuronal expression in Drosophila is linked to altered habituation, activity, and/or sleep. Our findings further establish the role of the cNT5-II family, particularly NT5DC2 and/or NT5DC3, in the nervous system.

Among the dNT5 genes, dNT5C, the orthologue of NT5DC2 and NT5DC3, showed the strongest evidence for an important neuronal role. Its expression was enriched in the adult brain. This finding is in line with publicly available single cell RNA sequencing data, which showed more dNT5C-positive cells than dNT5A-positive and dNT5B-positive ones in the brain43. Consistent with the robust expression in the brain, dNT5C also caused the strongest deficits in habituation learning upon pan-neuronal knockdown. Considering that habituation correlates with cognitive performance44 and NT5DC2 is linked to cognitive performance and educational attainment through multiple GWASs9, our findings also reinforce NT5DC2’s association with cognitive performance. NT5DC2 knockdown has been shown to increase the synthesis of catecholamines in a cellular model12. Increased monoaminergic signaling in the brain has consistently been shown to promote wakefulness across species45,46. Indeed, we found mild effects of dNT5C pan-neuronal knockdown on activity and sleep, though predominantly for the RNAi line producing the stronger knockdown. More generally, the habituation test appeared to be the most sensitive to dNT5C pan-neuronal knockdown. dNT5C knockdown has less influence on locomotor activity, sleep, and morphology of NMJ terminals. Further research is warranted to follow-up on the behavioral effects of NT5DC2 and the role of monoaminergic signaling therein.

Out of all cNT5-II family members, only NT5C2 had been studied for its neuronal role prior to our study. NT5C2 was shown to regulate protein translation in neural progenitor cells, and neuronal expression of dNT5B, orthologue of NT5C2 and NT5DC4, was shown to cause motor defects in a climbing assay2. Moreover, NT5C2 has the strongest association to neuropsychiatric disorders among the cNT5-II family members (Supplementary Table 1). Despite such evidence, neuronal knockdown of dNT5B did not alter neuropsychiatric disorder-related behaviors in the current study. It should be noted, however, that the outcome was based on the data from only one RNAi construct. Furthermore, as this induced dNT5B RNAi reduced dNT5B mRNA level by half, the knockdown might have been not efficient enough to alter behavior and synaptic morphology. In addition, despite previous report of motor defects upon neuronal dNT5B knockdown, we did not observe significantly affected motor function in our habituation assays, as illustrated by the effective initial jump response of dNT5B knockdown flies and similar number of flies jumping throughout the habituation assay. The difference between the two studies may be explained by the different behaviors (climbing versus startle response) that exploit different neuronal circuits, and hence are not directly comparable. Also, the two studies employed different genetic tools: Duarte et al.2 used elav-Gal4 in their study, while we used another pan-neuronal driver, nSyb-Gal4. While both drivers are widely used pan-neuronal drivers, differences in onset, promotor strength, and/or persistence in adulthood are likely to exist and can lead to different levels of knockdown in neuronal subpopulations.

For dNT5A, the orthologue of NT5DC1, we found that knockdown with RNAi2, associated with weaker knockdown, was accompanied by severe habituation deficits, while knockdown with RNAi1, associated with stronger knockdown, showed normal habituation. This is surprising, but following explanations might be given. First, RNAi-mediated silencing can also (partly) occur through repression of translation47. The degree of knockdown upon induction of RNAi2 might potentially be an underestimation. Second, despite the high predicted specificity of all RNAi lines utilized in this study, we cannot formally exclude an off-target effect. Third, the knockdown observed using the ubiquitous driver might incompletely reflect the knockdown induced by the neuronal driver. Fourth, knockdown with RNAi2 was accompanied by nominally reduced expression of dNT5C. Since dNT5C knockdown was associated with strong habituation deficits, reduced dNT5C level may potentially contribute to the habituation deficits detected in pan-neuronal RNAi2-mediated dNT5A knockdown. Future studies should investigate whether habituation deficits in this model was caused by altered dNT5C level or purely caused by altered dNT5A level. Prior to our study, NT5DC1 had only been linked to cognitive function and neuropsychiatric disorders through GWASs9. Our findings on dNT5A function in habituation learning, activity, and sleep support the hypothesis of NT5DC1 having a role in neuropsychiatric disorders and cognitive function.

Our findings should be viewed in the context of the strengths and limitations of this study. We used the animal model Drosophila melanogaster combined with a reverse genetics approach to study the function of dNT5 genes in behavior and synapse morphology to complement genetics studies and non-invasive research in humans. Using qRT-PCR, we determined the enrichment of each dNT5 genes in the brain relative to the rest of the body. Since qRT-PCR only allows to compare expression of the same gene or amplicon in multiple conditions, it is not possible to compare expression of the three genes with each other. An objective method that allow comparison is RNAseq. Such large scale genomic data is publicly available43, although it is not available at the time resolution of our experiments. The fly model provides a tissue-specific gene manipulation system combined with RNAi-mediated knockdown, which allowed the study of dNT5 gene functions specifically in neurons. However, RNAi-mediated knockdown is predominantly dependent on the specificity and efficiency of the RNAi construct. While we carefully chose RNAi lines with high s19 score (>0.99) to ensure specificity and incorporated UAS-Dcr2 element to enhance knockdown efficiency25, knockdown induced might not be sufficient to cause stronger effects, especially on activity and sleep. Moreover, in the current study, we only set out to study knockdown of the dNT5 genes, extrapolating from the few findings in humans linked to malfunctioning of the gene/protein and reduced gene expression. However, most links to human behavior come from GWAS, where it is still difficult to define the direction of effect of associated genetic variants. We therefore cannot exclude a role for overexpression of the dNT5 genes in the phenotypes studied here. More research is warranted to investigate the consequence of dNT5 gene overexpression in psychiatric disorders-related behavior.

In summary, we here confirmed existing evidence for a neuronal role of cNT5-II family members, and extended knowledge by reporting such a role also for NT5DC1, NT5DC2, and NT5DC3 using Drosophila as a model. The dNT5 genes impact habituation learning, activity, and sleep, providing supporting evidence that cNT5-II family genes can contribute to the etiology of neuropsychiatric disorders. Although research so far might have only been focused on the neurobiology of NT5C2, studying the neuronal role of other cNT5-II family members, especially NT5DC2 and NT5DC3, can provide additional insight into the biology underlying the neuropsychiatric disorders.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center and Vienna Drosophila RNAi center for providing transgenic fly stocks used in this study. We thank Michaela Fenckova for generating driver stock for habituation paradigm. This work was supported by grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) Innovation program in the Vici (grant 016-130-669 to Barbara Franke), TOP grant (912-12-109 to Annette Schenck), and Veni scheme (grant 91.614.084 to Monique van der Voet).

Conflict of interest

Barbara Franke has received educational speaking fees from Medice. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors jointly supervised this work: Annette Schenck, Barbara Franke

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41398-020-01149-x).

References

- 1.Zimmermann H. 5’-Nucleotidase: molecular structure and functional aspects. Biochem J. 1992;285:345–365. doi: 10.1042/bj2850345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duarte RRR, et al. The psychiatric risk gene NT5C2 regulates adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase signaling and protein translation in human neural progenitor cells. Biol. Psychiatry. 2019;86:120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.03.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kulkarni SS, et al. Suppression of 5’-nucleotidase enzymes promotes AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) phosphorylation and metabolism in human and mouse skeletal muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:34567–34574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.268292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jordheim, L. P. Expanding the clinical relevance of the 5’-nucleotidase cN-II/NT5C2. Purinergic Sig. 14, 321–329 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Dursun U, et al. Autosomal recessive spastic paraplegia (SPG45) with mental retardation maps to 10q24.3-q25.1. Neurogenetics. 2009;10:325–331. doi: 10.1007/s10048-009-0191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novarino G, et al. Exome sequencing links corticospinal motor neuron disease to common neurodegenerative disorders. Science. 2014;343:506–511. doi: 10.1126/science.1247363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elsaid MF, et al. NT5C2 novel splicing variant expands the phenotypic spectrum of Spastic Paraplegia (SPG45): case report of a new member of thin corpus callosum SPG-Subgroup. BMC Med. Genet. 2017;18:33. doi: 10.1186/s12881-017-0395-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Straussberg R, et al. Novel homozygous missense mutation in NT5C2 underlying hereditary spastic paraplegia SPG45. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2017;173:3109–3113. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watanabe K, et al. A global overview of pleiotropy and genetic architecture in complex traits. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:1339–1348. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0481-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duarte RRR, et al. Genome-wide significant schizophrenia risk variation on chromosome 10q24 is associated with altered cis-regulation of BORCS7, AS3MT, and NT5C2 in the human brain. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. 2016;171:806–814. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lane JM, et al. Biological and clinical insights from genetics of insomnia symptoms. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:387–393. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0361-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakashima A, et al. Identification by nano-LC-MS/MS of NT5DC2 as a protein binding to tyrosine hydroxylase: downregulation of NT5DC2 by siRNA increases catecholamine synthesis in PC12D cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019;516:1060–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.06.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zayats T, et al. Exome chip analyses in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Transl. Psychiatry. 2016;6:e923. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Hulzen KJE, et al. Genetic overlap between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder: evidence from genome-wide association study meta-analysis. Biol. Psychiatry. 2017;82:634–641. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laughlin RE, et al. Genetic dissection of behavioral flexibility: reversal learning in mice. Biol. Psychiatry. 2011;69:1109–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bier E. Drosophila, the golden bug, emerges as a tool for human genetics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005;6:9–23. doi: 10.1038/nrg1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.St Johnston D. The art and design of genetic screens: Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002;3:176–188. doi: 10.1038/nrg751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reiter LT, et al. A systematic analysis of human disease-associated gene sequences in Drosophila melanogaster. Genome Res. 2001;11:1114–1125. doi: 10.1101/gr.169101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lloyd TE, Taylor JP. Flightless flies: Drosophila models of neuromuscular disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010;1184:e1–e20. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05432.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Voet M, et al. ADHD-associated dopamine transporter, latrophilin and neurofibromin share a dopamine-related locomotor signature in Drosophila. Mol. Psychiatry. 2016;21:565–573. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein, M. et al. Contribution of intellectual disability-related genes to ADHD risk and to locomotor activity in Drosophila. Am. J. Psychiatry 177, 526–536 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Fenckova M, et al. Habituation learning is a widely affected mechanism in Drosophila models of intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorders. Biol. Psychiatry. 2019;86:294–305. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDiarmid TA, Bernardos AC, Rankin CH. Habituation is altered in neuropsychiatric disorders—a comprehensive review with recommendations for experimental design and analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017;80:286–305. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dietzl G, et al. A genome-wide transgenic RNAi library for conditional gene inactivation in Drosophila. Nature. 2007;448:151–156. doi: 10.1038/nature05954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stessman HAF, et al. Disruption of POGZ is associated with intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorders. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016;98:541–552. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graveley BR, et al. The developmental transcriptome of Drosophila melanogaster. Nature. 2011;471:473–479. doi: 10.1038/nature09715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leader DP, et al. FlyAtlas 2: a new version of the Drosophila melanogaster expression atlas with RNA-Seq, miRNA-Seq and sex-specific data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D809–D815. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Untergasser A, et al. Primer3-new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nijhof B, et al. A new Fiji-based algorithm that systematically quantifies nine synaptic parameters provides insights into Drosophila NMJ morphometry. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2016;12:e1004823. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castells-Nobau, A. et al. Two algorithms for high-throughput and multi-parametric quantification of Drosophila neuromuscular junction morphology. J. Vis. Exp.123, e55395 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Schindelin J, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donelson NC, et al. High-resolution positional tracking for long-term analysis of Drosophila sleep and locomotion using the “tracker” program. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e37250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosato E, Kyriacou CP. Analysis of locomotor activity rhythms in Drosophila. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:559–568. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sawamura N, et al. Nuclear DISC1 regulates CRE-mediated gene transcription and sleep homeostasis in the fruit fly. Mol. Psychiatry. 2008;13:1138–1148. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitchell KJ. The genetics of neurodevelopmental disease. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2011;21:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hall J, et al. Genetic risk for schizophrenia: convergence on synaptic pathways involved in plasticity. Biol. Psychiatry. 2015;77:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang J, et al. Genotype to phenotype relationships in autism spectrum disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 2015;18:191–198. doi: 10.1038/nn.3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Furukubo-Tokunaga K, et al. DISC1 causes associative memory and neurodevelopmental defects in fruit flies. Mol. Psychiatry. 2016;21:1232–1243. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coll-Tane, M. et al. Intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorders ‘on the fly’: insights from Drosophila. Dis. Model. Mech. 2019. 12, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Charng WL, Yamamoto S, Bellen HJ. Shared mechanisms between Drosophila peripheral nervous system development and human neurodegenerative diseases. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2014;27:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davie K, et al. A single-cell transcriptome Atlas of the aging Drosophila brain. Cell. 2018;174:982–98 e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kavšek M. Predicting later IQ from infant visual habituation and dishabituation: a meta-analysis. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2004;25:25. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2004.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nall A, Sehgal A. Monoamines and sleep in Drosophila. Behav. Neurosci. 2014;128:264–272. doi: 10.1037/a0036209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scammell TE, Arrigoni E, Lipton JO. Neural Circuitry of wakefulness and sleep. Neuron. 2017;93:747–765. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fukaya T, Tomari Y. MicroRNAs mediate gene silencing via multiple different pathways in drosophila. Mol. Cell. 2012;48:825–836. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.