Significance

Modern agriculture is dependent on the yearly application of large quantities of nitrogen fertilizer acquired via the chemical fixation of N2 in the Haber–Bosch process. More sustainable agricultural systems take advantage of biological nitrogen fixation, particularly the symbiosis between nitrogen-fixing bacteria called rhizobia and leguminous plants. A long-term goal of symbiotic nitrogen-fixation (SNF) research is to optimize its use in agriculture by improving rhizobia or by engineering symbiotic relationships into nonlegumes. Using the model rhizobium Sinorhizobium (Ensifer) meliloti, we establish that only 58 genes from the 1.35-Mb pSymA megaplasmid are required for effective SNF. This minimal SNF gene set, and genetic platform, have important implications for engineering approaches to optimize rhizobia inoculants and transfer symbiotic abilities to novel backgrounds.

Keywords: rhizobia, nitrogen fixation, synthetic biology, symbiosis, root nodule

Abstract

Reduction of N2 gas to ammonia in legume root nodules is a key component of sustainable agricultural systems. Root nodules are the result of a symbiosis between leguminous plants and bacteria called rhizobia. Both symbiotic partners play active roles in establishing successful symbiosis and nitrogen fixation: while root nodule development is mostly controlled by the plant, the rhizobia induce nodule formation, invade, and perform N2 fixation once inside the plant cells. Many bacterial genes involved in the rhizobia–legume symbiosis are known, and there is much interest in engineering the symbiosis to include major nonlegume crops such as corn, wheat, and rice. We sought to identify and combine a minimal bacterial gene complement necessary and sufficient for symbiosis. We analyzed a model rhizobium, Sinorhizobium (Ensifer) meliloti, using a background strain in which the 1.35-Mb symbiotic megaplasmid pSymA was removed. Three regions representing 162 kb of pSymA were sufficient to recover a complete N2-fixing symbiosis with alfalfa, and a targeted assembly of this gene complement achieved high levels of symbiotic N2 fixation. The resulting gene set contained just 58 of 1,290 pSymA protein-coding genes. To generate a platform for future synthetic manipulation, the minimal symbiotic genes were reorganized into three discrete nod, nif, and fix modules. These constructs will facilitate directed studies toward expanding the symbiosis to other plant partners. They also enable forward-type approaches to identifying genetic components that may not be essential for symbiosis, but which modulate the rhizobium’s competitiveness for nodulation and the effectiveness of particular rhizobia–plant symbioses.

Biological N2 fixation is catalyzed by an oxygen-sensitive metalloenzyme, nitrogenase, that is widely distributed in bacteria and archaea but is not found in eukaryotic organisms (1). A key group of N2-fixing bacteria from the α- and β-Proteobacteria, referred to as rhizobia, form N2-fixing nodules on the roots of leguminous plants such as clover, alfalfa, pea, and soybean (2). Over the past 50 years, many bacterial and plant genes that are involved in the symbiosis have been identified (3, 4), and initiatives are now underway to engineer the N2-fixation ability into major cereal crop plants that do not fix N2 (5, 6). Approaches that involve engineering root-nodule formation on nonleguminous crops will ultimately require recognition, invasion, and N2 fixation by bacteria that are “compatible” with the engineered plant host. Such a compatible symbiont must be recognized by the plant, tolerated by its immune system, and supplied with an energy source to carry out N2 fixation.

Compatibility between rhizobia and legumes is governed at the early stages by the production of a rhizobial signaling molecule, Nod Factor (synthesized by proteins encoded by nod/nol/noe genes), in response to plant flavones. Recognition of a compatible Nod Factor by legume LysM receptors triggers nodule organogenesis and physiological adjustments in the plant. In nodules, nitrogen fixation by rhizobia depends on the expression of nitrogenase (encoded by nif genes) and metabolic adaptation to the oxygen-limited environment of the nodule that includes producing a high O2-affinity cytochrome oxidase (encoded by fix genes) (7). Symbiosis genes are encoded on extrachromosomal replicons or integrative conjugative elements that allow the exchange of symbiotic genes by horizontal gene transfer (8). However, horizontal transfer of essential symbiotic genes (nod, nif, fix) alone is often not sufficient to convert a naive bacterium into a compatible symbiont for a legume (9). Therefore, elucidating the complete complement of genes required for the establishment of a productive symbiosis between rhizobia and legumes will be critical for future efforts to engineer symbiotic nitrogen fixation (SNF) in cereals. One approach to constructing compatible rhizobia for cereals is to engineer SNF into bacteria with a preexisting ability to colonize cereals (10). In this case, a suitable genetic platform for redesigning symbiosis gene clusters for broad host-range transfer would ameliorate these efforts, as Escherichia coli has for engineering free-living diazotrophy (11, 12).

The model rhizobium Sinorhizobium (Ensifer) meliloti forms symbiosis with legumes of the genera Medicago and Melilotus, including the important forage crop alfalfa (Medicago sativa) and the model legume Medicago truncatula. Symbiotic genes in S. meliloti are located on two large extrachromosomal replicons called pSymA and pSymB (13, 14). The pSymA megaplasmid is traditionally referred to as the symbiotic megaplasmid because it contains the nod, nif, and fix genes. The tripartite organization of the S. meliloti genome allows for massive genome reduction (∼45%), and we recently reported a strain in which both pSymA and pSymB were removed (15). We recognized that backgrounds lacking the extrachromosomal replicons represent a unique opportunity to use a gain-of-function approach to identify the minimum set of genes required by a rhizobium to engage in an effective symbiosis with its legume hosts. As a starting point, we identified single-copy regions of the megaplasmids required for symbiotic proficiency with alfalfa by screening an S. meliloti deletion library spanning >95% of genes on pSymA and pSymB (16).

In this study, we describe the identification of a minimal symbiotic gene complement from pSymA that is sufficient for the formation of N2-fixing root nodules and robust growth promotion of its legume hosts. Based on the minimal subset, we develop a transformative synthetic biology platform for future approaches to manipulating symbiotic genes.

Results

All pSymA Genes Essential for SNF Are Localized to Three Regions Totaling 162 kb (minSymA1).

The overall goal of this work was to identify a minimal gene set from the 1,354-kb pSymA megaplasmid that is necessary and sufficient for robust SNF on alfalfa. We assessed SNF using plant assays performed in pots containing a quartz sand–vermiculite growth substrate and a nitrogen-deficient nutrient solution. These conditions allowed for vigorous growth of plants, while also allowing for a robust measure of symbiotic nitrogen fixation based on shoot dry-weight accumulation.

To facilitate the genomic analyses, we removed pSymA from our wild-type S. meliloti RmP110 strain (termed ∆pSymA) and developed “landing pad” sites to allow targeted integration of the symbiotic gene clusters. A previous analysis of pSymA revealed that only the A117, A118, and A121 regions of pSymA are essential for SNF (16) (Fig. 1A). In the first version of the minimal symbiotic genome (minSymA1), we combined these regions and integrated them into the ∆pSymA strain. This was accomplished by deleting the A301 region separating A121 from A118 and then capturing the resulting ∼161-kb A117-A118-A121 region in E. coli (Materials and Methods). The A117-A118-A121 region was integrated into the ΔhypRE::FRT landing pad of pSymB (LP-B1) in S. meliloti RmP110 ΔpSymA, and we designated the resulting S. meliloti strain as minSymA1.0 (Fig. 1B).

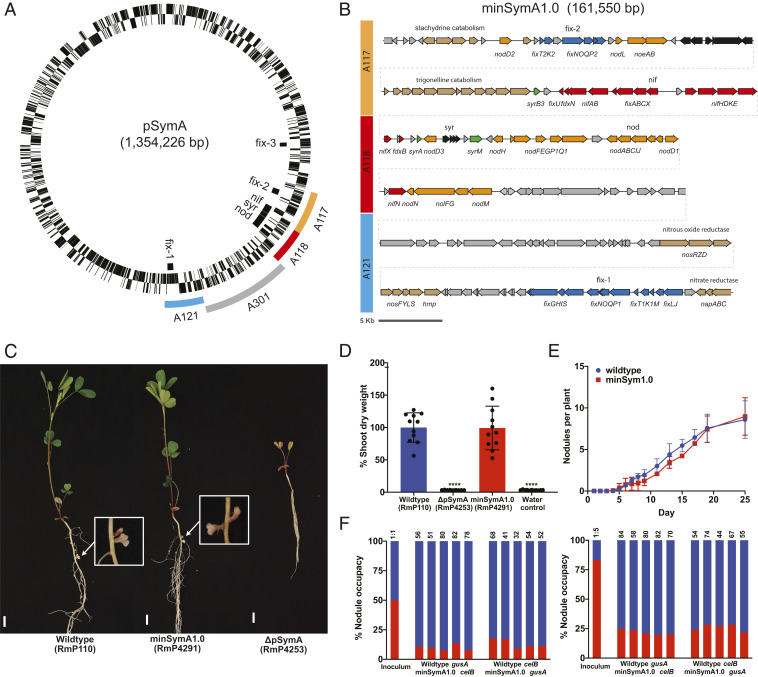

Fig. 1.

Isolation of the minimal symbiotic genome, minSymA1.0. (A) Circular map of the symbiotic megaplasmid pSymA from S. meliloti 1021 with symbiotic loci indicated inside the circle. The three essential symbiotic regions (A117, A118, and A121) as defined in diCenzo et al. (16) are colored outside the circle. The gray A301 region was deleted in order to bring the three essential symbiotic regions adjacent to one another. (B) Map of minSymA1.0 containing the A117, A118, and A121 symbiotic regions. Open reading frames (ORFs) and characterized genes are shown. Gene cluster names correspond to the locus designations in A. ORFs are colored according to their function as follows: orange—NF production and regulation, and nodulation efficiency; red—nitrogenase synthesis, assembly, electron supply, and regulation; blue—high-affinity terminal oxidase synthesis, assembly, and regulation; green—syr-associated transcriptional regulation; brown—other characterized metabolic genes not associated directly with SNF; gray—uncharacterized ORFs. (C) Images of alfalfa plants and nodules 31 d following inoculation with wild type, minSymA1.0, and ΔpSymA strains. (Scale bars, 1 cm.) (D) Relative shoot dry weight of M. sativa plants 35 to 38 d post inoculation. Wild type and minSymA1.0 were not significantly different in a one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (P = 0.9995); ****P < 0.0001 indicates significant difference from wild type. Each data point represents one independent replicate and is calculated from the average shoot dry weight in one pot (six plants per pot). (E) Kinetics of nodule formation on alfalfa for wild type compared to minSymA1.0. Data are the average of two independent experiments with 16 plants per experiment. (F) Competitiveness of minSymA1.0 (red) for nodule occupancy when coinoculated with wild type (blue). Data are presented from 10 pots including reversal of the marker gusA and celB genes as indicated. Plants were inoculated at a ratio of 50% minSymA1.0 (Left) and 80% minSymA1.0 (Right). Total number of nodules examined are indicated above each bar.

Alfalfa plants inoculated with minSymA1.0 formed N2-fixing nodules, and, remarkably, their shoot dry-weight (SDW) was statistically indistinguishable from plants inoculated with the wild-type RmP110 (Fig. 1 C and D). The wild-type and minSymA1.0 strains formed a similar number of nodules (7.42 ± 2.55 and 7.77 ± 1.02 nodules plant−1); their rates of N2 fixation as measured by acetylene reduction were also similar (SI Appendix, Table S1). Since minSymA1.0 removed such a significant portion of pSymA (∼1,100 genes), we extended our phenotypic characterization to test for compromises in earlier stages of the symbiotic lifestyle (17, 18). Using a chromogenic marker system (19), we found that, while minSymA1.0 and the wild-type form nodules at a similar rate (Fig. 1E), competitiveness for nodule occupancy is severely reduced in minSymA1.0 compared to the wild type (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1F). When present as 50% of the inoculum, 12% of nodules contain minSymA1.0, and when present as 80% of the inoculum, only 24% of nodules contain minSymA1.0. Thus, despite its robust SNF phenotype, the minSymA1.0 strain is outcompeted by the wild type. Presumably genes on pSymA that are not included in minSymA1.0 are important for earlier stages of the plant–microbe interaction, particularly in an ecological context in soil when competing bacteria are present.

Refinement of the Minimal Symbiotic Genome to 75 kb (minSymA2).

To refine and reduce the minimal pSymA symbiotic genome, we identified symbiotic loci within the 162-kb minimal pSymA of minSymA1.0 based on the literature (13, 20–29) and then sequentially combined these loci using yeast recombineering to generate a minSymA2.0 genome. Twelve fragments that carried known nod and nif loci from the A117-A118 region of minSymA1.0 were assembled and combined with three fragments containing the fix-1 locus of A121 (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2). The reassembled gene clusters retained their native promoters and gene order as present in the wild type. The resulting construct, bearing ∼62 kb of pSymA, was integrated into the ∆hypRE::FRT pSymB landing pad of strain RmP110 ∆pSymA to generate minSymA2.0. While minSymA2.0 was Nod+ Fix+ on alfalfa, SNF was clearly compromised and the plant SDW was only ∼30% of plants inoculated with the wild type (Fig. 2 B and G). To investigate the cause of this reduced symbiotic performance, first the fix-1 locus was examined and found to completely restore SNF to an A121 deletion; hence, no additional genes present in A121 are required for SNF (Fig. 2C). Next, minSymA2.0 was transferred to strains carrying deletions (ΔA401-ΔA406) that removed various subregions of the A117-A118 region (Fig. 2D); minSymA2.0 complemented the symbiotic phenotype of the ΔA402-ΔA406 deletions but not ΔA401 (Fig. 2E). Furthermore, the SDW of plants inoculated with ΔA401 was similar to that of plants inoculated by minSymA2.0 (∼30% wild type). The A401 region contains the fix-2 locus (Fig. 2D). Although this locus was previously described as dispensable for SNF (29), and was thus excluded from minSymA2.0, these data led us to hypothesize that the fix-2 locus is nevertheless required for efficient SNF. We assembled the fix-2 region and found that it restored the SDW of ΔA401 to wild-type levels when introduced (Fig. 2F). Finally the fix-2 region was transferred to minSymA2.0 to generate minSymA2.1. The dry weights of alfalfa plants inoculated with minSymA2.1 were statistically indistinguishable from the wild type (mean ∼80%) (Fig. 2 F and G), confirming that the nonessential fix-2 locus contributes to SNF efficiency.

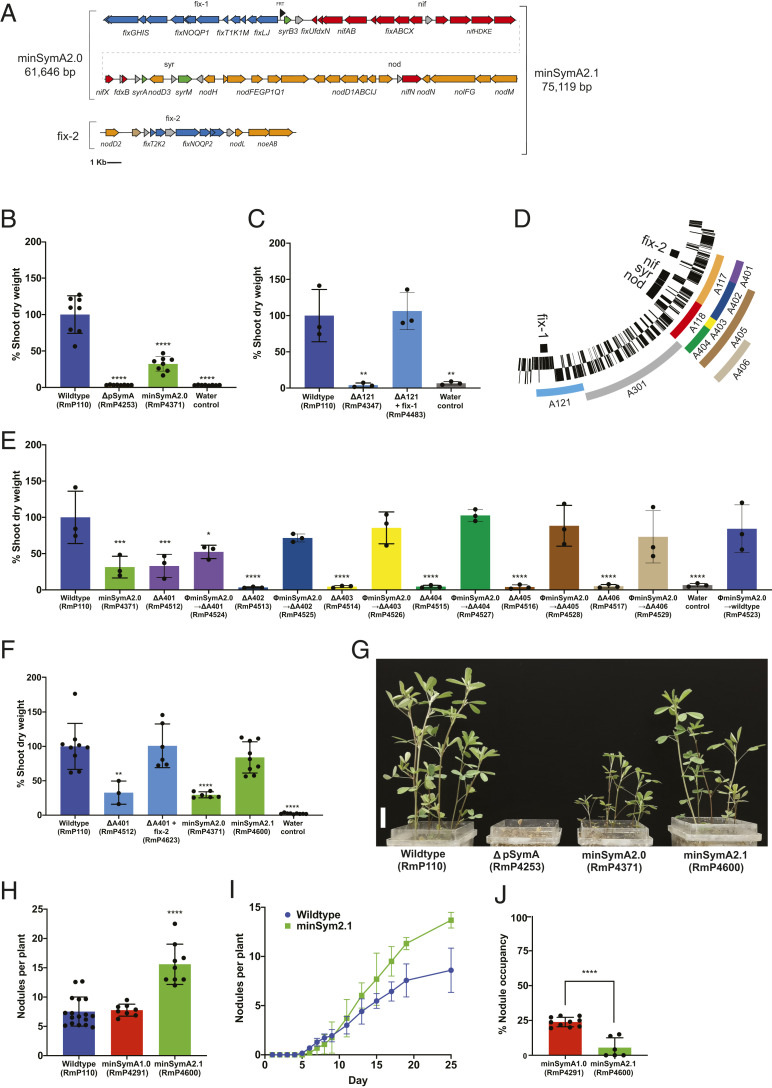

Fig. 2.

Symbiotic phenotypes of minSymA2.0 and minSymA2.1 assembled by yeast recombineering. (A) Map of minSymA2.0 and minSymA2.1, with genes represented as arrows. Annotations and coloring are as described in Fig. 1B. (B) Shoot dry weight of alfalfa inoculated with minSymA2.0 in a ΔpSymA background (38 d post inoculation). (C) Shoot dry weight of alfalfa inoculated with the ∆A121 mutant with and without the fix-1 locus assembled by yeast recombineering and integrated into the LP-B1. Shoot dry-weight measurements were taken 28 d post inoculation. (D) Map of pSymA subdeletions (E). Complementation of the ∆A401-∆A406 deletions with minSymA2.0 introduced by transduction (measured 28 d post inoculation). (F) Complementation of the ∆A401 deletion strain with the fix-2 locus and the SDW phenotype of minSymA2.1 (minSymA2.0 + fix-2) (38 d post inoculation). For B, C, E, and F, each data point represents one independent replicate and is calculated from the average shoot dry weight in one pot (six plants per pot). (G) Representative image of M. sativa plants in pots. The labels below each pot indicate the strain used as inoculum. (Scale bar, 2 cm.) (H) Average number of Fix+ nodules formed per plant by minSymA1.0 and minSymA2.1 compared to wild type. Each data point represents one independent replicate calculated from the average number of nodules per plant in one pot (six plants per pot). (I) Kinetics of nodule formation by minSymA2.1 compared to wild type. Data are the average of two independent experiments with 16 plants per experiment. (J) Percentage nodule occupancy of minSymA1.0 and minSymA2.1 when competed as 80% of the inoculum with the wild type. Each data point represents one independent replicate and is calculated from the proportion in one pot (four plants per pot). Shoot dry-weight assays and nodule number statistical significance was assessed with one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons tests and is presented compared to wild type. Significance of percentage nodule occupancy was tested with a two-way paired t test. For all significance testing: *P < 0.1, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Although the shoot dry weights were similar, alfalfa plants inoculated with minSymA2.1 (Fig. 2 F and G) contained significantly more root nodules compared to plants inoculated with the wild type or minSymA1.0 (Fig. 2H). Nodulation kinetics analyses revealed that wild type and minSymA2.1 initially formed nodules at similar rates (Fig. 2I); however, following the first appearance of pink nodules (∼7 d), a significantly increased rate of nodulation occurred in minSymA2.1. This result could reflect autoregulation of nodulation by the plant compensating for a limitation in symbiotic efficiency of minSymA2.1 nodules (30). We also considered that the genomic location where symbiotic gene clusters are integrated could influence their expression, but we found no evidence that the site of integration of the symbiotic genes alters the symbiotic performance of the strain (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

When assayed for nodulation competitiveness using 80% minSymA2.1 and 20% wild-type RmP110 in the inoculum, we observed an even greater impairment in competitiveness for nodule occupancy than that observed for minSymA1.0. On average, minSymA2.1 occupied ∼5% of nodules, and 50% of plants tested completely lacked minSymA2.1 (Fig. 2J).

Simplification and Functionalization of Symbiotic Genes (minSymA3).

To further streamline the minimal genome, we eliminated additional nonessential genes and generated distinct modules containing the functionally related nod, nif, and fix genes with their native promoters. Starting with minSymA2.0, the syr loci (nodD3, syrM, syrA, syrB3, and sma0809) were removed, and we repositioned nifN with the nif genes and nodL and noeAB with the other nod genes to generate minSymA3.0 (Fig. 3A). Alfalfa inoculated with minSymA3.0 had substantially reduced SDW compared to the those inoculated with wild type, and, as in the case of minSymA2.0, the addition of the fix-2 locus (giving minSymA3.1) resulted in near wild-type levels of N2 fixation (Fig. 3B). Moreover, as in the case of minSymA2.1, an increased nodule number phenotype was observed for minSymA3.1 (∼17 ± 4 nodules plant−1, P < 0.0001 vs. wild type).

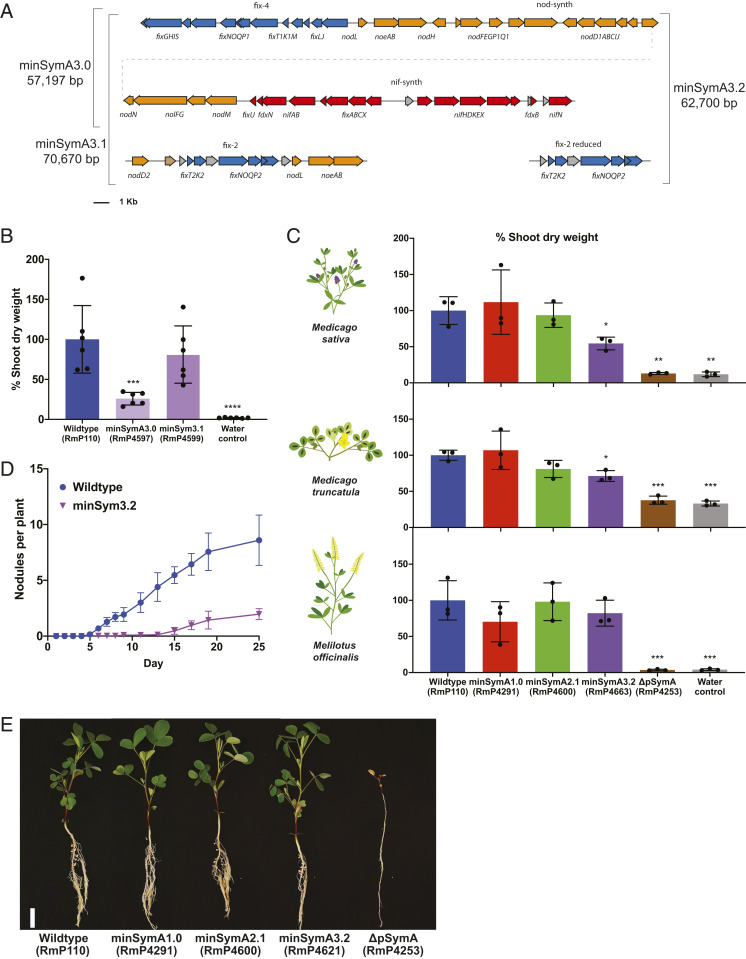

Fig. 3.

Functionalization and simplification of the minimal symbiotic genome. (A) Map of the gene contents of minSymA3.0, minSymA3.1, and minSymA3.2. Genes are represented as arrows. Annotations and coloring are as described in Fig. 1B. (B) Shoot dry weight of alfalfa plants inoculated by minSymA3.0 and minSymA3.1 (38 d post inoculation). (C) Comparison of shoot dry weight of three different legume hosts inoculated with wild type, minSymA1.0, minSymA2.1, or minSymA3.2 (31 d post inoculation). For B and C, each data point represents one independent replicate and is calculated from the average shoot dry weight in one pot (six plants per pot for M. sativa and four plants per pot for M. truncatula and M. officinalis). (D) Kinetics of nodule formation on alfalfa inoculated with minSymA3.2 compared to wild type. (E) Images of M. officinalis plants inoculated with S. meliloti minSymA strains (31 d post inoculation). (Scale bar, 2 cm.) Data are the average of two independent experiments with 16 plants per experiment. For shoot dry-weight assays, statistical significance was assessed with one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test and is presented compared to wild type. *P < 0.1, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

To place the transcriptional activation of the nod genes exclusively under the control of NodD1, the transcriptional regulator nodD2 was removed along with duplicated copies of nodLnoeAB to create minSymA3.2, which then contained just 63 kb of DNA from pSymA (58 of 1,290 protein-coding genes) (Fig. 3A). Considering the known host-dependent phenotypes associated with loss of nodD2 (31), in characterizing minSymA3.2, symbiotic assays were performed with the model legume M. truncatula and a representative from the Melilotus genus, Melilotus officinalis, in addition to alfalfa (SI Appendix, Table S1). The minSymA1.0, minSymA2.1, and minSymA3.2 strains were symbiotically proficient on the three host plants, and, while the shoot dry weight of M. sativa and M. truncatula inoculated with minSymA3.2 appeared reduced relative to plants inoculated with wild type (∼55 and 70%, respectively), that reduction was not statistically significant for M. officinalis (∼80% wild type) (Fig. 3 C and E and SI Appendix, Figs. S4 and S5). This observation is consistent with the increased role of NodD2 in nodulation of Medicago species that has been observed previously (31, 32). Nodule kinetics data for M. sativa inoculated with minSymA3.2 revealed a severe impairment in the rate of nodule formation (Fig. 3D), which is likely reflected in the reduced dry-weight phenotype (Fig. 3C).

Adapting minSymA3 as a Synthetic Biology Platform.

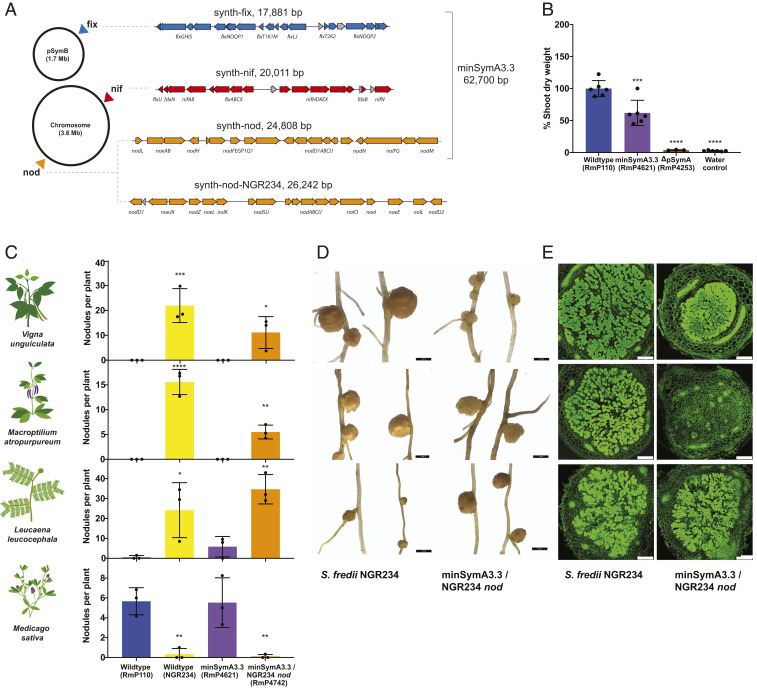

An ideal synthetic biology platform for manipulating SNF would consist of distinct nod, nif, and fix clusters to facilitate their independent manipulation. To this end, we split the functionalized nod, nif, and fix elements in minSymA3.2 into separate DNA fragments and integrated them at unlinked positions across the S. meliloti genome (minSymA3.3) (Fig. 4A). The symbiotic performance of minSymA3.3 was consistent with that of minSymA3.2 (Figs. 4B and 3C). As a proof of concept to demonstrate the utility of this platform, we amplified the Sinorhizobium fredii NGR234 nod/nol/noe genes from four locations in its genome and assembled them as a 26-kb synthetic nod cluster that we integrated into the S. meliloti genome in place of the S. meliloti nod genes in minSymA3.3 (Fig. 4A). S. fredii NGR234 is known for its ability to nodulate the broadest host range of any rhizobia. Engineered S. meliloti with the heterologous Nod Factor gained the ability to elicit root nodule formation on Vigna unguiculata (cow pea), Macroptilium atropurpureum (siratro), and Leucaena leucocephala (Fig. 4 C and D). Although the nodules were ineffective, significant numbers of bacteroids were visualized inside plant cells of V. unguiculata and L. leucocephala nodules, indicating that nodule invasion continued past the infection stage (Fig. 4E and SI Appendix, Fig. S6).

Fig. 4.

Symbiotic phenotypes of minSymA3.3 modules and chimera with NGR234 nod genes. (A) Schematic showing the locations where the nod, nif, and fix symbiotic clusters were integrated into the S. meliloti genome. Map of the synthetic nod, nif, and fix clusters with genes represented as arrows. Annotations and coloring are as described in Fig. 1B. (B) Shoot dry-weight accumulation by S. meliloti hosts inoculated with an S. meliloti strain with synth-nod, synth-nif, and synth-fix integrated into different locations in the genome. Each data point represents one independent replicate and is calculated from the average shoot dry weight in one pot (six plants per pot). (C) Nodule formation on S. fredii NGR234 hosts by S. meliloti minSymA3.3 engineered with NGR234 nod genes (28 d post inoculation). Each data point represents one independent replicate and is calculated from the average number of nodules per plant in one pot (six plants per pot for M. sativa, four plants per pot for V. unguiculata and M. atropurpureum, and two plants per pot for L. leucocephala). (D) Light microscopy images of representative nodules formed by S. fredii NGR234 and S. meliloti minSymA3.3 engineered with NGR234 nod genes. (Scale bars, 2 mm.) (E) Confocal microscopy of nodules formed by S. fredii NGR234 and S. meliloti minSymA3.3 engineered with NGR234 nod genes. (Scale bars, 250 μm.) For shoot dry-weight assays and nodule number, statistical significance was assessed with one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test and is presented compared to wild-type S. meliloti. *P < 0.1, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Discussion

We define the minimal symbiotic genome as a horizontally acquired group of genes that are required for the formation of N2-fixing root nodules on leguminous plants. Based on previous failed attempts to confer effective SNF to related nonrhizobia by transfer of rhizobia symbiotic plasmids (4), we believe a minimal group of symbiotic genes will function only when present in a compatible genomic background such that, when the two gene sets are combined, the resulting organism can form functional N2-fixing root nodules. The compatible genomic background that we employ here is S. meliloti lacking the 1,354-kb pSymA megaplasmid.

We used a sequential, iterative approach to reduce the pSymA megaplasmid from 1,354-kb to a 63-kb region (58 genes) that is sufficient for the formation of N2-fixing root nodules on alfalfa (M. sativa), M. truncatula, and M. officinalis. This report describes the manipulation of these genes with a goal of defining a minimal functional gene complement, and thus is an important step toward the synthetic manipulation of these genes. A key consideration in this work was a desire to construct a minimal genome that retained high levels of symbiotic N2 fixation in robust plant growth assays, and we achieved that goal. Achieving this required inclusion of the reiterated fix genes in the fix-2 locus (fixTKNOQP2). A requirement for two copies of fixNOQP for effective SNF has been reported in other rhizobia (33, 34), although the reason for this requirement is not understood. The 63-kb minSymA3.2 genome formed effective symbiosis with M. sativa, M. truncatula, and M. officinalis, producing shoot dry-weight values from 50 to 80% of wild type (Fig. 3C).

Further reduction of the minimal 63-kb gene complement described here is possible as several nod, nif, and fix genes that we have included are not absolutely essential for SNF. However, we focused here on maintaining effective symbiosis, and their removal would undoubtedly reduce SNF or disrupt transcriptional units bearing essential symbiotic genes. Based on genome sequence data, many other rhizobia maintain smaller complements of SNF genes than those of S. meliloti. One of the smallest is recognized as a 35-kb region present on a 560-kb plasmid in Cupriavidus taiwanensis LMG19424 (35). While not functionally characterized, the C. taiwanensis symbiotic cluster is considerably smaller than the S. meliloti minimal pSymA reported here. The discrepancy is partially a result of a significantly expanded set of nod genes in S. meliloti that may reflect differences in the recruitment of other genes to tailor the interactions to different host plants, e.g., permissive and nonpermissive host plants (36). A second major difference is the absence of fix genes encoding the high-affinity terminal electron acceptor required for symbiosis in the C. taiwanensis cluster, likely functionally replaced by homologous genes on the chromosome (35).

Based on our ability to recover nodule formation and nitrogen fixation exclusively with nod, nif, and fix clusters, all of the bacterial genes from pSymA involved in fundamental aspects of the root-nodule symbiosis in laboratory conditions appear to be known. However, our data suggest that, in natural field conditions, the minSymA strains would be severely out-competed by resident rhizobia. Presumably, many genes present on the pSymA megaplasmid, such as the rhizobactin siderophore gene cluster (15), play roles in growth and survival in soil environments. Competition for nodule occupancy is an important trait for the success of rhizobial inoculants in agriculture (37). Defining the minimal symbiotic genome facilitates gain-of-function approaches that can now be used to elucidate pSymA genes, as well as genes from other highly competitive rhizobia, that contribute to nodulation competitiveness. Similarly, gain-of-function approaches could be used to investigate the genetic basis of the substantial variance in compatability observed between different S. meliloti strains and their legume hosts (38).

Manipulating the minimal symbiotic genome provides a crucial foundation for future approaches to engineering of the symbiosis, be it altering host range, increasing N2-fixation efficiency, or engineering symbionts that can establish a symbiosis with major nonlegume crops. The functionalized nod, nif, and fix elements in minSymA3.3 facilitate independent manipulation of these gene clusters. To this end, we demonstrated the feasibility of engineering S. meliloti to elicit nodule formation on nonnative host plants by replacing the S. meliloti minimal nod gene cluster with a 26-kb synthetic nod cluster from S. fredii NGR234 (Fig. 4). The inability of these nodules to fix nitrogen suggests the presence of additional host-range determinants and highlights the complexities of altering the rhizobium host range. Engineering LysM Nod-factor (NF) receptors of legumes to perceive the NF from noncognate symbionts has recently been accomplished (39). Together with exchanging the nod cluster of minSymA3.3 with those from other rhizobia, these approaches could enable investigations into the factors beyond NF signaling that govern the compatibility between legumes and their cognate rhizobial partners. Such research will undoubtedly be critical to engineering symbiotic nitrogen fixation in cereal crops.

While pSymA, long referred to as the symbiotic megaplasmid, contains the genes most directly associated with SNF, other genes that are essential for SNF are present on the 1,683-kb pSymB chromid including those for the metabolism of C4-dicarboxylates and exopolysaccharide biosynthesis. We are presently using the workflows established here to identify a minimal pSymB complement that is sufficient for SNF. In addition, the genetic predispositions or adjustments required to allow a bacterium to evolve into a symbiotic nitrogen fixer are unclear (9). In this respect, assuming that nod, nif, and fix genes are appropriately expressed, it will be interesting to investigate whether this minSymA or individual minSym regions can also function in other phylogenetically related and distant strains.

Materials and Methods

Microbial Growth Conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in SI Appendix, Table S2. Complex and defined media used for growth of E. coli (LB) and S. meliloti (LBmc, M9) were used as described previously along with growth conditions and antibiotic concentrations (15, 16). Saccharomyces cerevisiae was cultured with yeast extract peptone dextrose (YPD) complex medium, and synthetic complete (SC) defined medium lacking histidine or uracil. All yeast media were supplemented with 40 mg•L−1 adenine sulfate.

Genetic Manipulations.

Routine conjugations from E. coli to S. meliloti were performed by triparental mating including the E. coli MT616 helper strain in addition to the donor and recipient (40). Transductions between S. meliloti strains were performed using the ΦM12 bacteriophage (41).

Deletion Construction.

The ΔA401-ΔA406 deletions were constructed with the Flp-FRT method by flanking the region to be excised through single-crossover homologous recombination of plasmids bearing FRT sites (pTH1937 [Neomycin (Nm)R] and pTH3291 [Gentamicin (Gm)R]) as described previously (42).

In Vivo Capture of A117, A118, and A121.

RmP4219 (ΔA301) was used as a starting point for the capture of the symbiotic regions A117, A118, and A121. First, the FRT scar and associated sequences between A118 and A121 from ΔA301 were removed by sacB-mediated double homologous recombination (43) with pTH3237. Plasmid pTH3237 was made by combining DNA from the ends of A118 (pSymA nucleotide [nt] 506,533 to 507,338) and A121 (pSymA nt 623,673 to 624,173) in pTH2919 (SI Appendix, Table S2 and Fig. S1). To mediate excision of the now-adjacent A117-A118-A121 regions, FRT sites were introduced directly upstream of A117 and downstream of A121 by ΦM12 transduction of the integrated vector backbones of pTH1522 (A117) and pTH1937 (A121) from RmP938 and RmP946, respectively. The resulting strain, RmP4309, was then used for in vivo cloning of A117-A118-A121 (16). Briefly, a plasmid carrying a protocatechuate (PCA)-inducible Flp recombinase (pTH2505) was introduced to RmP4309 by conjugation to generate RmP4310. RmP4310 was used in a triparental mating with RifR E. coli DH5α as a recipient. The mating was performed on LBmc with 2.5 mM PCA to induce Flp recombinase. Flp-mediated recombination resulted in the excision of A117-A118-A121 as a GmR, NmR plasmid that was captured and maintained in E. coli via p15A and pMB1 origin of replication elements from the pTH1522 and pTH1937 backbones (SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

Assembly of Symbiotic Regions by Yeast Recombineering.

For assembly of symbiotic regions, ∼4-kb DNA fragments were amplified by PCR with Q5 High Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs) and pTH3255 plasmid template DNA to maximize fidelity. Approximately 40 bp of homology on the ends of each amplicon was used to guide linear assembly into YAC/BAC (yeast/bacterial artificial chromosome) shuttle vectors and was incorporated into fragment design or added to PCR primers when relevant. Transformation of the linearized vectors and amplified fragments into S. cerevisiae VL6-48 was performed using the high-efficiency LiAc/SS carrier DNA/PEG method (44). Assembly of a circular plasmid in recombinants was selected using SC-H minimal medium based on histidine prototrophy. S. cerevisiae colonies were screened for the presence of symbiotic regions by PCR using primers from consecutive fragments. Putative correct plasmid assemblies were isolated from S. cerevisiae using the protocol described by Brumwell et al. (45) and transformed by electroporation into Lucigen TransforMax EPI300 E. coli. Plasmids were then isolated from Epi300 strains following copy number induction with L-arabinose and verified by restriction digest pattern (typically with BamHI, EcoRI, and HindIII) and ultimately Illumina sequencing once integrated into the S. meliloti genome.

For assembly of pTH3278, the fix-1 locus was amplified as three fragments and assembled into pAGE3.0 linearized with ClaI/I-SceI (to remove S. meliloti repABC and Phaeodactylum tricornutum selectable marker). An FRT site was introduced upstream of fixL, and the I-SceI site was reconstituted for future rounds of cloning. For assembly of pTH3294, the nif, syr, and nod loci were amplified as 12 fragments and assembled into pTH3278 linearized with I-SceI. The FRT/attB integration vectors pTH3369 and pTH3370 were constructed by amplifying the FRT/attB sites from pTH2884 as a 262-bp fragment and cloning into pAGE1.0 and pAGE2.0, respectively, via ClaI/I-SceI.

For assembly of pTH3372, the fix-2 locus was amplified as three fragments and assembled into pTH3369 linearized with PacI. The synthetic nod and synthetic nif clusters were assembled independently via PacI into pTH3369 and pTH3370 as seven and five fragments, respectively, to construct pTH3371 (synth-nod) and pTH3373 (synth-nif). They were also combined and added to the fix-1 locus as a 12-fragment assembly into pTH3278 linearized with I-SceI to construct pTH3375 (plasmid for minSymA3.0). The fix genes from the fix-2 locus were assembled individually into pTH3369 via PacI (pTH3396) and combined with fix-1 into a synthetic fix cluster (synth-fix) by assembly into pTH3278 via I-SceI (pTH3376).

Primers used to amplify fragments for symbiotic cluster assembly, and the pSymA genomic location of each fragment for symbiotic cluster assembly, are indicated in SI Appendix, Table S3.

Curing of pSymA from RmP110.

Incompatibility was used to cure RmP110 of pSymA by sequential conjugation with pTH2993 (to supply antitoxins) and pTH2992 (pSymA incα incompatibility element). Putative ΔpSymA colonies were identified based on the inability to utilize trigonelline as a sole carbon source and by PCR. The spontaneous curing of pTH2992 was screened for based on Gm sensitivity, and pTH2993 was removed by introducing a plasmid bearing an isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible I-SceI meganuclease (pJG592). IPTG (1 mM) was included in the selection medium, and transconjugants were screened for loss of pTH2992 based on spectinomycin (Sp) sensitivity. Finally, spontaneous curing of pJG592 was screened for based on tetracycline (Tc) sensitivity, resulting in RmP4247 (RmP110 ΔpSymA). Ultimately, the absence of pSymA and other plasmids was verified by genome sequencing of the minSymA strains assembled from this background.

Construction of Landing Pads for Integration of Symbiotic Regions.

LP-B1 was constructed in the ΔpSymA background by transducing a pSymB ΔhypRE::FRT-kan-FRT cassette (pSymB nt 272,683 to 273,672) (46) into RmP4247 (RmP110 ΔpSymA). The kan cassette was removed by introduction of pTH2505 (Flp) and a NmS TcR colony was purified and designated RmP4253. The resulting single FRT site (ΔhypRE::FRT) served as LP-B1, with integration catalyzed by Flp recombinase expressed from pTH2505.

For landing-pad LP-C1, we utilized a ΦC31 attB site that was previously integrated at nucleotide position 3,234,050 in the chromosome of RmP110 (47). Strains RmP2667 (SmR, TcR) and RmP1685 (SmR, NmR) that were used for plasmid integration also contained an IPTG-inducible ΦC31 integrase gene integrated elsewhere in the chromosome (47). To separate the integrated DNA from the ΦC31 integrase gene, and to place it in the desired background, including a ΔpSymA background, the integrated DNA was transferred by transduction with selection for the antibiotic resistance marking the integrated DNA.

For landing-pad LP-C2, we utilized an FRT site generated during the deletion of the chromosomal gene manB in RmP2227 (replaces chromosome nt 2,082,053 to 2,084,585) (48).

All landing pads were constructed at a distance (>200 kb apart) sufficient for integrated constructs to be combined by ΦM12 transduction.

Integration of Plasmids Bearing Symbiotic Regions.

We utilized two approaches to integration of plasmids bearing symbiotic regions into the S. meliloti genome. We took advantage of the reversible nature of FRT-FRT Flp-mediated recombination to catalyze integration of plasmids that contained a single FRT site (from excision of symbiotic regions in the case of pTH3255 or introduced in primers during yeast recombineering) into strains bearing FRT landing pads. We also used ΦC31 integrase to introduce plasmids bearing attP sequences into attB landing pads in the genome. (SI Appendix, Figs. S1 and S2).

To construct RmP4291 (minSymA1.0), pTH3255 was introduced into RmP4253 (contains LP-B1 and pTH2505) by triparental mating, and Flp recombinase was induced by including 2.5 mM protocatechuate in the mating spot. S. meliloti transconjugants with integrated pTH3255 were selected for using M9 minimal medium with 10 mM trigonelline as a sole carbon source (the A117 region in pTH3255 contains the trigonelline catabolism gene cluster) and streptomycin (Sm). Transconjugants were further screened for GmR, and single colony purified three times to give RmP4291. To validate integration into LP-B1, transduction of RmP4291 with a wild-type RmP110 ΦM12 lysate was selected with M9 minimal medium with 10 mM L-hydroxyproline as a sole carbon source. Transductants that recovered the ability to grow using hydroxyproline were screened for the ability to grow on LBmc containing Nm and Gm, and all failed to grow. The expected integration into the FRT site was later verified by genome sequencing of RmP4291.

Integration of yeast-assembled pTH3278 into LP-B1 to form RmP4346 was performed similarly by triparental mating. In these cases, the donor E. coli strain Epi300 was SmR, and so was counterselected based on an inability to grow on M9 minimal medium supplemented with Nm and 10 mM galactose as the sole carbon source (counterselection of E. coli based on leucine auxotrophy and galactose catabolism mutation). NmR transconjugants were patch plated onto Tc to identify strains that had lost the unstable flp plasmid pTH2505. A NmR TcS colony was selected and purified. Correct insertion into the ΔhypRE::FRT site was verified by the L-hydroxyproline utilization transduction strategy described above and by verifying the inability of L-Hyp+ transductants to grow on LBmc with Nm. Plasmids derived from pTH3278 were integrated into LP-B1 in the RmP4253 background and verified in the same way, including pTH3295 (minSymA2.0/RmP4371), pTH3275 (minSymA3.0/RmP4597), and pTH3376 (synth-fix/RmP4598). The expected integration into the FRT site of pTH3295, pTH3275, and pTH3376 was later verified at the nucleotide level by genome sequencing of RmP4371, RmP4621, and RmP4663.

Integration of pTH3372 (fix-2) into LP-C1 in RmP2667 to create RmP4532 was performed by attB/attP recombination via ΦC31 integrase. A triparental mating was performed to conjugate pTH3372 into RmP2667, and 0.5 mM IPTG was included in the LBmc medium for mating spot incubation to induce the integrase. Selection was performed as described above on M9 minimal medium with galactose as a sole carbon source and with Sp to select for plasmid integration. A SpR colony was selected and purified. We used a workflow that we developed previously for verification of correct integration into this attB site on the chromosome (47). We transduced the SpR-marked integrant into the methionine auxotroph RmP1615, which contains a metH::Tn5 (NmR) insertion ∼5 kb upstream of LP-C1. We then verified NmS and methionine prototrophy phenotypes in >90% of transductants, which indicated that the SpR plasmid was integrated into LP-C1. The integrated plasmid was introduced to RmP4371 (minSymA2.0) and RmP4597 (minSymA3.0) by transduction to form RmP4600 (minSymA2.1) and RmP4599 (minSymA3.1). The fix-2 cluster in pTH3396 was integrated and validated in the same way to create RmP4661 and transduced into RmP4597 to produce RmP4663 (minSymA3.2). Integration of pTH3373 (synth-nif) into LP-C1 to form RmP4612 was performed in the TcS LP-C1 background RmP1685. All other steps were as described above except TcR was used for selection. Ultimately, correct integrations were confirmed by genome sequencing.

To allow integration into LP-C2, pTH2505 was introduced by triparental mating. Next, pTH3375 or pTH3434 were introduced from Epi300 by triparental mating, Flp recombinase from pTH2505 was induced in the mating spot with 2.5 mM PCA, and integrants were selected with M9 minimal medium with Sp and galactose as the sole carbon source. SpR colonies (RmP4618/RmP4737) were purified, and integration into the manB FRT site was verified by transducing the SpR integrant into a wild-type RmP110 background and by testing the tranductants for loss of the ability to grow using arbutin as a sole carbon source [phenotype resulting from loss of manB (48)] on M9 minimal medium. The expected integration was later confirmed by genome sequencing of RmP4621 and RmP4741.

Generation of Chromogenic Marker Strains for Evaluating Competition for Nodule Occupancy.

To evaluate S. meliloti strains for competitiveness, we utilized the chromogenic marker system based on nodule-specific expression of gusA (β-glucuronidase) and celB (thermostable β-galactosidase) (19). We integrated PnifH-controlled gusA and celB (49) into an intergenic region downstream of the pheA gene in the S. meliloti chromosome as the integration site (chromosome nt 257,195 to 257,274) and devised a workflow based on phenylalanine auxotrophy to allow transfer of integrated gusA and celB genes to other S. meliloti backgrounds by two-step transduction. A Tn5-233 insertion in pheA that results in phenylalanine auxotrophy can be transduced into chosen backgrounds by selecting for GmR or SpR, and then markerless gusA or celB genes can be introduced by cotransduction with a functional pheA allele by selecting for phenylalanine prototrophy.

Plasmids for integration of PnifH::gusA and PnifH::celB into the S. meliloti genome were assembled in two steps. First, DNA flanking the chromosomal integration site (chromosome nt 256,639 to 257,195, and chromosome nt 257,274 to 257,640) were amplified from the S. meliloti genome and assembled on either side of PnifH::gusA or PnifH::celB amplified from pOGG0253 or pOGG0254 by three-fragment Level 1 Golden Gate cloning into the vector pOGG024 as previously described (49) to produce pTH3362 (gusA) and pTH3383 (celB). Next, the three fragments were amplified from pOGG024 as a single amplicon and cloned into pJQ200SK via XbaI/PstI. The resulting plasmids, pTH3364 (gusA) and pTH3385 (celB), were introduced into the S. meliloti RmP110 genome by single crossover in a triparental mating selecting for Sm Gm resistance. Double homologous recombinants were selected by streaking SmR GmR transconjugants on LBmc with 5% sucrose and screening for colonies that were now GmS, resulting in RmP4505 (RmP110 gusA) and RmP4506 (RmP110 celB). Correct integration of gusA and celB in the genome was verified by PCR.

To transfer gusA and celB to the minSymA1.0 background, pheA::Tn5-233 was first transduced from RmG340 to RmP4219, and a SpR Phe− transductant (RmP4507) was purified and then transduced to Phe+ with ΦM12 lysates of RmP4505 and RmP4506, respectively, and selection with M9 minimal medium. The resulting strains were verified as SpS and were designated as RmP4508 (minSymA1.0 gusA) and RmP2509 (minSymA1.0 celB). The same strategy was used to transfer gusA and celB to the minSymA2.0 background, and then the fix-2 cluster was introduced, creating RmP4645 (minSymA2.1 gusA) and RmP4646 (minSymA2.1 celB).

Genome Sequencing and Analysis.

Genomic DNA from S. meliloti strains with symbiotic plasmids integrated into the genome were sequenced with Illumina HiSeq at the Farncombe Family Digestive Health Research Institute at McMaster University. Reads were aligned to a map of the expected genome sequence [derived from the S. meliloti 1021 reference genome (50)] with Geneious R11 software (mapper: Geneious; sensitivity: medium sensitivity/fast; fine-tuning: up to five iterations; reads not trimmed). The sequence of integrations was evaluated manually for possible mutations, and in one case an ambiguous region in fixT of RmP4371 was amplified by PCR and confirmed to be as expected by Sanger sequencing. DNA sequencing of minSymA2.0 (∼62 kb) revealed that its sequence was as predicted from the Rm1021 sequenced genome except for a single missense mutation (H389 to Y) within the coding sequence of NifB. This mutation had no apparent effect on the N2-fixing symbiosis as minSymA2.0 completely complemented the Fix− phenotypes of the ΔA402 and ΔA405 deletions that removed nifB (Fig. 2E). DNA sequencing of the regions integrated in minSymA1.0, minSymA3.2, and minSymA3.3 confirmed a complete match to the expected sequence from the Rm1021 genome sequence.

Symbiotic Assays.

For SNF assays, plants were grown in Leonard jar assemblies with a 1:1 (wt/wt) mixture of quartz sand and vermiculite, and 250 mL of Jensen’s medium (51). Each Leonard jar contained six to eight seedlings, and they were inoculated 2 d after planting with 10 mL of water containing ∼107 rhizobial cells/mL.

M. sativa cv. Iroquois (alfalfa), M. truncatula A17 (barrel medic), M. officinalis (yellow sweet clover), V. unguiculata (cow pea), M. atropurpureum (siratro), and L. leucocephala (river tamarind) were used for plant assays. M. sativa seeds were sterilized with 95% ethanol for 5 min, followed by 2.5% sodium hypochlorite for 20 min. Seeds were then washed with sterile water for 1 h, replacing the water every 15 min. M. truncatula and M. officinalis seeds were first scarified with anhydrous sulfuric acid for 12 min until small black spots were observed on the tegument surface. They were washed several times with sterile water and then sterilized with 2.5% sodium hypochlorite for 2 min and rinsed again with sterile water five to six times. V. unguiculata, M. atropurpureum, and L. leucocephala were scarified with anhydrous sulfuric acid for 8, 10, and 12 min, respectively, and washed extensively with sterile water. The treated seeds were germinated in the dark for 2 d on 0.9% agar plates prior to planting. Competition for nodulation assays were conducted with four seedlings per jar, which were inoculated 2 d post planting with a predefined ratio of two strains (marked with gusA and celB), totaling 104 cells per jar. Nodule occupancy was assessed by sequential staining with Magenta-glc and X-gal following thermal treatment essentially as described previously (19), except X-gal staining was incubated for 2 d to enhance blue-color formation in nodules.

Plants were grown in Conviron E15 growth chambers with incandescent and fluorescent lights or in Conviron Adaptis A1000 growth chambers with LED lights set to maximum. Chambers were programmed with a day setting of 21 °C for 18 h and a night setting of 17 °C for 6 h for S. meliloti hosts and a day setting of 28 °C for 12 h and a night setting of 20 °C for 8 h for S. fredii hosts. Plant shoots were harvested and dried at 55 °C to a constant weight (for 1 to 2 wk) and weighed. Roots were removed from sand/vermiculite and rinsed with water, and the visibly Fix+ (pink) nodules were counted. To assess nodule wet weight, Fix+ nodules were picked from the roots as they were counted and weighed immediately. The absence of nodules on the water control verified lack of cross-contamination, and strains were routinely cultured from nodules and screened for antibiotic resistance phenotypes to verify that nodules were formed by the appropriate inoculant strain.

Acetylene reduction assays were performed by gas chromatography using a HP6890 gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies) as previously described (52). Rates of acetylene reduction were determined based on a linear rate of ethylene produced across 18 min.

Confocal microscopy of nodules was performed as previously described (52).

Nodule kinetics were established by visible assessment of nodule organ formation on Jensen’s 1% agar slopes (20 mL) in glass tubes. Sixteen seedlings were inoculated with 100 μL of ∼107 rhizobial cells/mL of water, and nodules were counted every day for the first 9 d and then every 2 d.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sukhnoor Bindra for assistance curing pSymA from RmP110; Lisa Situ for creating the landing pad strain RmP4253; Dick Morton and past members of the T.M.F. laboratory for advice and multiple strain constructions; Joel Griffitts for the gift of plasmid pJG592; and Bogumil Karas for discussions and advice regarding assembly in yeast.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2018015118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

All study data are included in the article and supporting information.

References

- 1.Dixon R., Kahn D., Genetic regulation of biological nitrogen fixation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 621–631 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masson-Boivin C., Giraud E., Perret X., Batut J., Establishing nitrogen-fixing symbiosis with legumes: How many rhizobium recipes? Trends Microbiol. 17, 458–466 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roy S., et al. , Celebrating 20 years of genetic discoveries in legume nodulation and symbiotic nitrogen fixation. Plant Cell 32, 15–41 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.diCenzo G. C., et al. , Multidisciplinary approaches for studying rhizobium-legume symbioses. Can. J. Microbiol. 65, 1–33 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mus F., et al. , Symbiotic nitrogen fixation and the challenges to its extension to nonlegumes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82, 3698–3710 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oldroyd G. E. D., Dixon R., Biotechnological solutions to the nitrogen problem. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 26, 19–24 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oldroyd G. E. D., Murray J. D., Poole P. S., Downie J. A., The rules of engagement in the legume-rhizobial symbiosis. Annu. Rev. Genet. 45, 119–144 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geddes B. A., Kearsley J., Morton R., diCenzo G. C., Finan T. M., “The genomes of rhizobia” in Advances in Botanical Research, Frendo P., Frugier F., Masson-Boivin C., Eds. (Elsevier, 2020), Vol. 94, pp. 213–249. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doin de Moura G. G., Remigi P., Masson-Boivin C., Capela D., Experimental evolution of legume symbionts: What have we learnt? Genes (Basel) 11, 339 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geddes B. A., et al. , Use of plant colonizing bacteria as chassis for transfer of N2-fixation to cereals. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 32, 216–222 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang X., et al. , Using synthetic biology to distinguish and overcome regulatory and functional barriers related to nitrogen fixation. PLoS One 8, e68677 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Temme K., Zhao D., Voigt C. A., Refactoring the nitrogen fixation gene cluster from Klebsiella oxytoca. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 7085–7090 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnett M. J., et al. , Nucleotide sequence and predicted functions of the entire Sinorhizobium meliloti pSymA megaplasmid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 9883–9888 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finan T. M., et al. , The complete sequence of the 1,683-kb pSymB megaplasmid from the N2-fixing endosymbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 9889–9894 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.diCenzo G. C., MacLean A. M., Milunovic B., Golding G. B., Finan T. M., Examination of prokaryotic multipartite genome evolution through experimental genome reduction. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004742 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.diCenzo G. C., Zamani M., Milunovic B., Finan T. M., Genomic resources for identification of the minimal N2-fixing symbiotic genome. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 2534–2547 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Göttfert M., et al. , At least two nodD genes are necessary for efficient nodulation of alfalfa by Rhizobium meliloti. J. Mol. Biol. 191, 411–420 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bromfield E. S., Lewis D. M., Barran L. R., Cryptic plasmid and rifampin resistance in Rhizobium meliloti influencing nodulation competitiveness. J. Bacteriol. 164, 410–413 (1985). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sánchez-Cañizares C., Palacios J., Construction of a marker system for the evaluation of competitiveness for legume nodulation in Rhizobium strains. J. Microbiol. Methods 92, 246–249 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruvkun G. B., Sundaresan V., Ausubel F. M., Directed transposon Tn5 mutagenesis and complementation analysis of Rhizobium meliloti symbiotic nitrogen fixation genes. Cell 29, 551–559 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klipp W., Reiländer H., Schlüter A., Krey R., Pühler A., The Rhizobium meliloti fdxN gene encoding a ferredoxin-like protein is necessary for nitrogen fixation and is cotranscribed with nifA and nifB. Mol. Gen. Genet. 216, 293–302 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Earl C. D., Ronson C. W., Ausubel F. M., Genetic and structural analysis of the Rhizobium meliloti fixA, fixB, fixC, and fixX genes. J. Bacteriol. 169, 1127–1136 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swanson J. A., Mulligan J. T., Long S. R., Regulation of syrM and nodD3 in Rhizobium meliloti. Genetics 134, 435–444 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mulligan J. T., Long S. R., A family of activator genes regulates expression of Rhizobium meliloti nodulation genes. Genetics 122, 7–18 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kondorosi E., Banfalvi Z., Kondorosi A., Physical and genetic analysis of a symbiotic region of Rhizobium meliloti: Identification of nodulation genes. Mol. Gen. Genet. 193, 445–452 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horvath B., et al. , Organization, structure and symbiotic function of Rhizobium meliloti nodulation genes determining host specificity for alfalfa. Cell 46, 335–343 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Batut J., et al. , Localization of a symbiotic fix region on Rhizobium meliloti pSym megaplasmid more than 200 kilobases from the nod-nif region. Mol. Gen. Genet. 199, 232–239 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kahn D., et al. , Rhizobium meliloti fixGHI sequence predicts involvement of a specific cation pump in symbiotic nitrogen fixation. J. Bacteriol. 171, 929–939 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Renalier M. H., et al. , A new symbiotic cluster on the pSym megaplasmid of Rhizobium meliloti 2011 carries a functional fix gene repeat and a nod locus. J. Bacteriol. 169, 2231–2238 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mortier V., De Wever E., Vuylsteke M., Holsters M., Goormachtig S., Nodule numbers are governed by interaction between CLE peptides and cytokinin signaling. Plant J. 70, 367–376 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Györgypal Z., Iyer N., Kondorosi A., Three regulatory nodD alleles of diverged flavonoid-specificity are involved in host-dependent nodulation by Rhizobium meliloti. Mol. Gen. Genet. 212, 85–92 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Honma M. A., Asomaning M., Ausubel F. M., Rhizobium meliloti nodD genes mediate host-specific activation of nodABC. J. Bacteriol. 172, 901–911 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reyes-González A., et al. , Expanding the regulatory network that controls nitrogen fixation in Sinorhizobium meliloti: Elucidating the role of the two-component system hFixL-FxkR. Microbiology (Reading) 162, 979–988 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schlüter A., et al. , Functional and regulatory analysis of the two copies of the fixNOQP operon of Rhizobium leguminosarum strain VF39. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 10, 605–616 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amadou C., et al. , Genome sequence of the β-rhizobium Cupriavidus taiwanensis and comparative genomics of rhizobia. Genome Res. 18, 1472–1483 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Meyer S. E., et al. , Symbiotic Burkholderia species show diverse arrangements of nif/fix and nod genes and lack typical high-affinity cytochrome cbb3 oxidase genes. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 29, 609–619 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Triplett E. W., Sadowsky M. J., Genetics of competition for nodulation of legumes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 46, 399–428 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sugawara M., et al. , Comparative genomics of the core and accessory genomes of 48 Sinorhizobium strains comprising five genospecies. Genome Biol. 14, R17 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bozsoki Z., et al. , Ligand-recognizing motifs in plant LysM receptors are major determinants of specificity. Science 369, 663–670 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Finan T. M., Kunkel B., De Vos G. F., Signer E. R., Second symbiotic megaplasmid in Rhizobium meliloti carrying exopolysaccharide and thiamine synthesis genes. J. Bacteriol. 167, 66–72 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Finan T. M., et al. , General transduction in Rhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 159, 120–124 (1984). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Milunovic B., diCenzo G. C., Morton R. A., Finan T. M., Cell growth inhibition upon deletion of four toxin-antitoxin loci from the megaplasmids of Sinorhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 196, 811–824 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quandt J., Hynes M. F., Versatile suicide vectors which allow direct selection for gene replacement in gram-negative bacteria. Gene 127, 15–21 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gietz R. D., Schiestl R. H., High-efficiency yeast transformation using the LiAc/SS carrier DNA/PEG method. Nat. Protoc. 2, 31–34 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brumwell S. L., et al. , Designer Sinorhizobium meliloti strains and multi-functional vectors enable direct inter-kingdom DNA transfer. PLoS One 14, e0206781 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.White C. E., Gavina J. M., Morton R., Britz-McKibbin P., Finan T. M., Control of hydroxyproline catabolism in Sinorhizobium meliloti. Mol. Microbiol. 85, 1133–1147 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.diCenzo G., Milunovic B., Cheng J., Finan T. M., The tRNAarg gene and engA are essential genes on the 1.7-Mb pSymB megaplasmid of Sinorhizobium meliloti and were translocated together from the chromosome in an ancestral strain. J. Bacteriol. 195, 202–212 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kibitkin K., Transport and Metabolism of β-Glycosidic Sugars in Sinorhizobium meliloti (McMaster University, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Geddes B. A., Mendoza-Suárez M. A., Poole P. S., A bacterial expression vector archive (BEVA) for flexible modular assembly of golden gate-compatible vectors. Front. Microbiol. 9, 3345 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Galibert F., et al. , The composite genome of the legume symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti. Science 293, 668–672 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vincent J. M., A Manual for the Practical Study of Root-Nodule Bacteria (Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1970). [Google Scholar]

- 52.diCenzo G. C., Zamani M., Cowie A., Finan T. M., Proline auxotrophy in Sinorhizobium meliloti results in a plant-specific symbiotic phenotype. Microbiology (Reading) 161, 2341–2351 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and supporting information.