Abstract

Aim:

The aim of this study is to compare the diagnosis of patients with temporomandibular joint (TMJ) internal derangements which had been diagnosed using Research Diagnostic Criteria/Temporomandibular Disorders (RDC/TMD) with the dynamic high resolution sonography findings.

Settings and Design:

Axis I section of RDC/TMD form had been applied to participants. Participants were divided into three groups as healthy TMJ, disc displacement with reduction, and disc displacement without reduction. The diagnoses had been compared with the dynamic high-resolution sonography findings.

Materials and Methods:

Twelve of the patients had been treated with laser therapy, whereas 13 patients were treated with stabilization splint. Seventeen patients were treated with anterior repositioning splint (n = 42). After the application of different treatment modalities, the position of the articular disc had been determined with Axis I of RDC/ TMD form and dynamic high-resolution sonography. The findings were compared and statistically analyzed.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Statistical analyses of data were analyzed with Turcosa Cloud (Turcosa Ltd Co, Turkey).

Results:

For the right TMJ, pretreatment and posttreatment ultrasonography (USG) diagnoses and RDC/ TMD clinical diagnoses were found similar (κ = 0.125–0.008). No statistically significant relationship was found (P > 0.05). For the left TMJ, pretreatment USG diagnosis and RDC/TMD clinical diagnose were found similar (κ = 0.070). No statistically significant relationship was found (P > 0.05). For the left TMJ, posttreatment USG diagnosis and RDC/TMD clinical diagnose were compared. A statistically significant difference was found (κ = 0.256). A statistically significant relationship was found (P < 0.05).

Conclusions:

Axis 1 of RDC/TMD form which is used for the diagnosis of internal derangements and dynamic high resolution sonography was not found in the agreement.

Keywords: Disk displacement, dynamic high-resolution sonography, temporomandibular joint

INTRODUCTION

The most common reason for temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction is disc displacement which is described as the abnormal relationship between disc and condyle.[1] Anterior disc displacement with reduction (ADDWR) is defined as the disc-condyle relationship which is seated with a “click” noise during mouth opening. In ADDWR, the mandible deviates to the affected side until the click and then returns to the midline during mouth opening.[1,2,3] Anterior disc displacement without reduction (ADDWoR) may develop with the progress of this clinical condition. Deflection of the midline to the affected side can be observed in addition to severely limited mouth opening. The protrusive movement which accompanies the deflection to the affected side is also limited.[3,4]

Imaging indications of temporomandibular disorders (TMD) are unsuccessful conservative treatment, the presence of worsening symptoms or atypical symptoms and preoperative evaluation.[1,2] Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is considered as the gold standard to diagnose TMD, relatively low availability and high-cost cause MRI to be disadvantageous as an imaging method.[2,5,6] Conventional imaging techniques that can be available in almost all dental clinics such as panoramic radiography, depicts only the late degenerative changes in TMJ. Computed tomography (CT) and cone-beam CT (CBCT) cannot produce the images of soft tissues such as the articular disc. Besides, the use of CT/CBCT as a routine scanning method is not recommended due to high radiation dose.[2]

Dynamic high-resolution sonography is defined as a noninvasive, inexpensive, easily accessible, and safe imaging method to diagnose TMJ disc displacement and degenerative diseases.[7] In addition, there are studies reporting that MRI is in excellent agreement with ultrasonography (USG).[8] It has been reported that specifically 12.5 MHz ultrasound provides much more reliable results to identify disc displacement.[9]

The aim of this study is to compare the diagnosis of patients who had TMJ internal derangement diagnosis with Research Diagnostic Criteria/TMDs (RDC/TMD) questionnaire with dynamic high-resolution sonography findings. Furthermore, low dose laser and two different occlusal splints (centric relation splint and anterior positioning splint) therapies were applied and the status of TMD was evaluated again with RDC/TMD axis I and USG. The null hypothesis of the study was “there is agreement between the RDC/TMD axis I form which was used to identify TMJ internal derangements and dynamic high-resolution sonography.”

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was carried out with 42 patients (10 male and 32 female) who had referred to Erciyes University Faculty of Dentistry Department of Prosthodontics with the complaints of TMJ pain, limited mandibular movements and TMJ noises. Patients' age was between 18 and 60 years old, the mean age was 25.88 ± 10.41 [Table 1]. Ethical approvals were taken from Erciyes University Clinical Researches Ethics Committee (Decision no: 2016/04). The participants were informed, and the written consent forms were obtained.

Table 1.

Comparison of age and sex between study groups

| Groups | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior repositioning splint (n=17) | Stabilisation splint (n=13) | Laser (n=12) | Total (n=42) | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 3 (17.6) | 3 (23.1) | 4 (33.3) | 10 (23.8) | 0,601 |

| Female | 14 (82.4) | 10 (76.9) | 8 (66.7) | 32 (76.2) | |

| Age | 29.00±10.62 | 27.30±12.66 | 19.91±2.93 | 25.88±10.41 | 0.054 |

Data were given as n (%) and mean±SD. Age and gender distributions of the groups were found statistically insignificant (P>0.05). SD: Standard deviation

Axis I section of RDC/TMD form was applied to the patients who were included in the study. The joints were divided into three groups as healthy TMJs, ADDWR, and ADDWoR.

Seventeen patients were treated with anterior repositioning splint, 13 patients with stabilisation splint, and 12 of them were treated with low-dose laser therapy. The treatment groups were determined randomly.

After 6 months of the treatment period, all patients were re-evaluated with RDC/TMD Axis I and dynamic high-resolution sonography. Two diagnosis methods were compared.

Research diagnostic criteria/temporomandibular disorders

RDC/TMD form which is accepted internationally and considered as the reference index was used to identify whether the patients had TMJ internal derangements.[10]

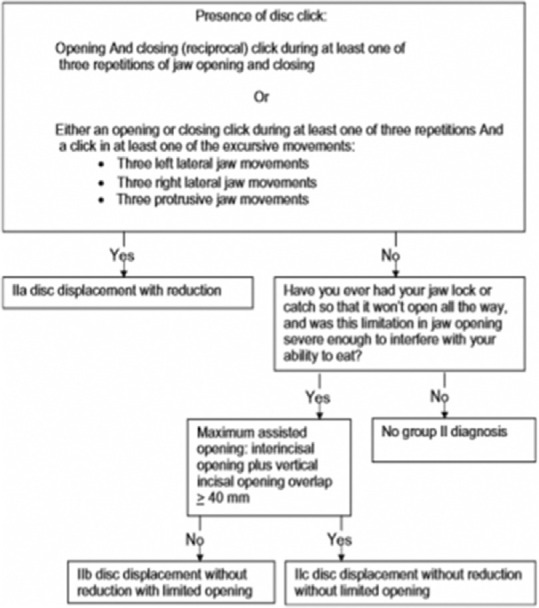

A diagnosis algorithm was established to identify these patients. RDC/TMD axis I group II diagnosis algorithm diagram which requires separate examination of right and left joints was shown in Figure 1.[11] RDC/TMD consists of two axises. Axis I is a clinical examination form and used for the diagnosis of TMDs. Axis II is a questionnaire form which provides information about the deficiencies and depression due to pain and the correlation between the psychosocial status and TMD.

Figure 1.

Revised Group II Disc Displacements diagnostic algorithm (Reprinted by permission from the Journal of Orofacial Pain 2010;24:70)

In the present study, the Turkish translation of RDC/TMD questionnaire which was recommended by the International RDC/TMD Consortium was used.[12] The evaluation of data obtained with RDC/TMD was performed according to the recommendations of Dworkin and LeResche.[10] Clinical examinations were performed by a single investigator (R. E.) according to these guidelines in the present study.

Ultrasonographic examination

The ultrasonographic examinations were performed to diagnose internal derangements. The procedures were carried out in Erciyes University Department Faculty of Dentistry by a dentomaxillofacial radiologist (M. E.) who had more than 5 years of experience in USG. The examinations were performed for both right and left sides using B-mode and high-frequency linear scanning transducer (14–7.2 MHz; PLT-1204 BT) USG device (AplioTM 500; Toshiba Medical Systems Corporation, Otawara, Japan).

A water-based gel was used to prevent possible air entrance between the probe and the skin. The examinations were performed while the participants were sitting. Transducers were positioned on TMJ in horizontal and longitudinal plane and the lateral pole of the transducer was placed contacting to the tragus. The normal articular disc was screened as a thin homogeneous hypoechoic structure in glenoid fossa with a more defined mandibular condyle echogenicity. Patients were instructed to open their mouths slowly to maximum mouth opening and to close. The static examination was performed while the mouth was in the closed and fully open position, followed by the dynamic examination which was performed during the joint opening. The scannings were repeated a few times for each joint. Examiner was blind to patients' clinic data.

TMJ disc displacement in USG was classified according to the following criteria:

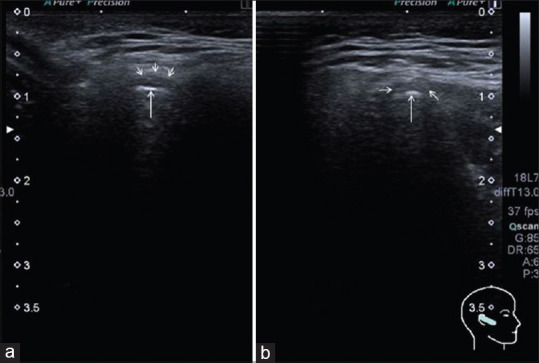

Normal disc position: In closed mouth position and the maximum opening, the articular disc is seated on the condyle head [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Normal disc position. a: closed mouth, b: open mouth

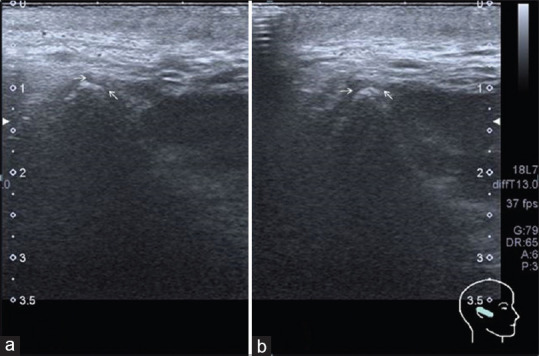

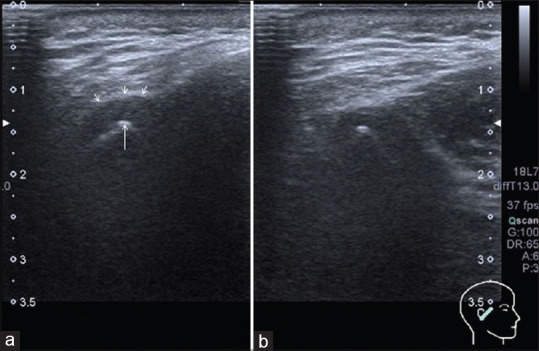

Disc displacement with reduction: In closed mouth position, the articular disc is anterior to the mandibular condyle. In the translation of the condyle to articular eminence, the disc is seated on the condyle [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Disc displacement with reduction. a: closed mouth, b: open mouth

Disc displacement without reduction: In closed mouth position, the articular disc is anterior to the condyle. In the maximum mouth opening, the articular disc cannot reduce to its normal position. The articular disc is seated in the anterosuperior of the condyle [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Disc displacement without reduction. a: closed mouth, b: open mouth

Statistical analyses

The normal distribution of the data was evaluated with histogram, q-q graphics, and Shapiro-Wilk test. The relationship between the qualitative variables was analyzed with the Pearson Chi-square test. The agreement between USG and clinical diagnosis was evaluated with the Kappa test. One-way variation analyses (ANOVA) was used for quantitative variables in intergroup comparisons. Statistical analyses of data were analyzed with Turcosa Cloud (Turcosa Ltd Co, Turkey) A significance level was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Forty-two patients (10 male 328%], 32 [76.2%] female) who were aged between 18 and 60 years old participated in this study. The mean age of the participants was 25.88 ± 10.41 [Table 1].

Patients in the treatment groups were evaluated with RDC/TMD form at the beginning of the treatment and after the treatment (6th month). Intragroup and intergroup comparisons were made.

For the right TMJ, pretreatment and posttreatment USG diagnoses and RDC/TMD clinical diagnoses were found similar (κ = 0.125–0.008). No statistically significant relationship was found (P > 0.05) [Table 2].

Table 2.

The evaluation of agreement between ultrasonography and research diagnostic criteria/temporomandibular disorder diagnoses for right temporomandibular joint (pre- and post-treatment)

| Parameters | Right TMJ RDC/TMD diagnosis pretreatment | κ | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | ADDWR | ADDWoR | Total | |||

| Right TMJ USG diagnosis pretreatment | ||||||

| Normal | 2 (13.3) | 10 (66.7) | 3 (20.0) | 15 (100.0) | 0.125 | 0.223 |

| ADDWR | 2 (7.7) | 23 (88.5) | 1 (3.8) | 26 (100.0) | ||

| ADDWoR | 0 | 1 (100.0) | 0 | 1 (100.0) | ||

| Total | 4 (9.5) | 34 (81.0) | 4 (9.5) | 42 (100.0) | ||

| Parameters | Right TMJ RDC/TMD diagnosis posttreatment | κ | P | |||

| Normal | ADDWR | ADDWoR | Total | |||

| Right TMJ USG diagnosis posttreatment | ||||||

| Normal | 10 (43.5) | 10 (43.5) | 3 (13.0) | 23 (100.0) | 0.008 | 0.941 |

| ADDWR | 6 (33.3) | 7 (38.9) | 5 (27.8) | 18 (100.0) | ||

| ADDWoR | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | ||

| Total | 17 (40.5) | 17 (40.5) | 8 (19.0) | 42 (100.0) | ||

Data were given as n (%). Right TMJ pretreatment USG and RDC/TMD diagnoses were compared. No statistically significant relationship was found (P>0.05). Right TMJ posttreatment USG and RDC/TMD diagnoses were compared. No statistically significant relationship was found (P>0.05). RDC/TMD: Research diagnostic criteria/temporomandibular disorders, TMJ: Temporomandibular joint, USG: Ultrasonography, ADDWR: Anterior disc displacement with reduction, ADDWoR: Anterior disc displacement without reduction

For the left TMJ, pretreatment USG diagnosis and RDC/TMD clinical diagnose were found similar (κ = 0.070). No statistically significant relationship was found (P > 0.05) [Table 3].

Table 3.

The evaluation of agreement between ultrasonography and research diagnostic criteria/temporomandibular disorders diagnoses for left temporomandibular joint (pre- and post-treatment)

| Parameters | Left TMJ RDC/TMD pretreatment diagnosis | κ | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | ADDWR | ADDWoR | Total | |||

| Left TMJ USG diagnosis pretreatment | ||||||

| Normal | 2 (11.8) | 14 (82.4) | 1 (5.9) | 17 (100.0) | 0.070 | 0.444 |

| ADDWR | 1 (4.0) | 22 (88.0) | 2 (8.0) | 25 (100.0) | ||

| ADDWoR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total | 3 (7.1) | 36 (85.7) | 3 (7.1) | 42 (100.0) | ||

| Parameters | Left TMJ RDC/TMD posttreatment diagnosis | κ | P | |||

| Normal (%) | ADDWR (%) | ADDWoR (%) | Total (%) | |||

| Left TMJ USG diagnosis posttreatment | ||||||

| Normal | 11 (47.8) | 7 (30.4) | 5 (21.7) | 23 (100.0) | 0.256 | 0.037 |

| ADDWR | 5 (26.3) | 13 (68.4) | 1 (5.3) | 19 (100.0) | ||

| ADDWoR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total | 16 (38.1) | 20 (47.6) | 6 (14.3) | 42 (100.0) | ||

Data was given as n (%). Left TMJ pretreatment USG and RDC/TMD diagnoses were compared. No statistically significant relationship was found (P>0.05). Left TMJ posttreatment USG and RDC/TMD diagnoses were compared. A statistically significant relationship was found (P<0.05). RDC/ TMD: Research diagnostic criteria/temporomandibular disorders, TMJ: Temporomandibular joint, USG: Ultrasonography, ADDWR: Anterior disc displacement with reduction, ADDWoR: Anterior disc displacement without reduction

For the left TMJ, posttreatment USG diagnosis and RDC/TMD clinical diagnose were compared. A statistically significant difference was found (κ = 0.256). A statistically significant relationship was found (P < 0.05) [Table 3].

DISCUSSION

TMD are widespread health problems that affect a considerable portion of the population. TMD-related facial pain may adversely affect daily life of patients. More and more patients are referring to dentists for TMD treatment. In the United States, it was reported that overall management cost of TMD has reached to $4 billion annually without the imaging cost.[13] MRI is considered as the gold standard to examine TMJ soft-tissue structures.[14] Although MRI provides excellent information about TMJ structures, it has significant disadvantages such as being expensive and having necessity of advanced equipment. These aforementioned disadvantages led clinicians to search a more practical imaging modality for TMD. An inexpensive and simple diagnostic technique is needed for the imaging of TMJ and especially the follow-up after treatments. High-frequency USG seems to be promising due to technologic developments in transducers and previous researches.

USG is recommended for the examination of TMDs due to its acceptable sensitivity and considerable advantages compared to MRI (inexpensive, allows to use with patients who have pacemakers, metallic implants, and claustrophobia).[15] It is an operator-dependent technique. Real-time images which were evaluated by expert radiologists may provide information about the displacement of TMJ disc through dynamic sonography during maximum mouth opening.[7] Kundu et al.[15] evaluated the usefulness of USG to determine TMDs in their review. An overview of related articles revealed that the sensitivity of USG to determine disc displacement is 41%–90% (compared to MRI as the gold standard). In their study, it was also shown that sensitivity increases with higher transducer frequency.

Based on high-resolution sonograms, a previous study reported the diagnostic accuracy as follows: The presence of internal derangements, disc displacement with reduction, disc displacement without reduction were 95%, 92%, and 90%, respectively.[16] Uysal et al.[8] stated that agreement of MRI and USG is excellent in the presence of TMJ intracapsular derangement. A similar study reported that specificity as 16%–94% and sensitivity as 66%–91%.[17] Hence, several authors reported that identifying the disc displacement through 12.5 MHz USG provides more reliable results.[17] In the presented study, internal derangements were identified using 14 MHz high-frequency linear scanning transducer.

Jank et al. evaluated 132 TMJs which had the internal derangement diagnosis via high-resolution USG.[18] They reported that both sensitivity and accuracy of USG as 78% compared to MRI which is considered as the gold standard to identify soft-tissue pathologies.

Our study population of 42 participants indicated a higher incidence of internal derangements of TMJ in women than in men, in line with previous studies.[19,20,21] This may be related to women's greater sensitivity to health, higher levels of stress hormones, their use of oral contraceptives, or other factors.[22,23]

The onset of symptoms occurs mostly between the ages of 20 and 40 years,[24] and our findings were within this range (mean age of onset, 25.88 ± 10.41). The symptoms of joint derangement are more noticeable in children and young adults,[25] and people over the age 60 years rarely complain of TMJ derangement symptoms.[26] In fact, the main difference between TMJ derangement and other joint derangements is that it has a higher incidence in young people.[27] This may be due to the self-limiting nature of the derangement and higher levels of anxiety and stress in younger people.

In the present study, a total of 42 TMJs were examined and three different treatment modalities were applied. The articular disc position was evaluated with dynamic high-resolution sonography. Imaging procedures were performed before and after treatment.

Axis I of RDC/TMD is a reliable examination tool to diagnose patients with disc displacement with reduction which had been used for years.[10,12] DC/TMD is a recent diagnostic tool which had been announced after RDC/TMD.[13] The presented study is a part of a doctoral thesis which had been started in 2014. Therefore, before DC/TMD was announced, most of the study groups were included in the study and their treatment had been initiated. For this reason, RDC/TMD was used to diagnose disc displacement with reduction in this study.

RDC/TMD is a questionnaire form that had been used in epidemiological and clinical controlled researches since 1992.[28,29] In 2012, Park et al. compared the diagnoses obtained from MRI and TMD/RDC form.[30] In their study, Cohen kappa value was determined as 0,336. No agreement was found between two diagnostic methods. Naeije et al. evaluated the usefulness of RDC/TMD to diagnose the patients with ADDWR.[31] They stated that the use of RDC/TMD can be misleading. It may conclude a false positive or negative result. Therefore it was not reported as a valuable diagnostic tool for TMD.

Given the high costs of TMD treatment, highly accurate and easily accessible diagnostic methods are required in both the diagnosis and the effectiveness of treatment. USG is a more accessible and less expensive imaging method compared to MRI.

In the present study, the authors performed USG examinations and RDC/TMD questionnairies before and after treatment. Thus, the agreement between USG and RDC/TMD form was compared twice.

Since USG is an operator dependent technique, all diagnoses were made by a single operator, unaware of the clinical diagnosis, to avoid different interpretations from the operator.

In the present study, for the patients with temporomandibular internal derangements, there is no statistically significant agreement between the dynamic high-resolution sonography and RDC/TMD Axis I form in general. Therefore, the null hypothesis was rejected. However, this result also supports the findings of RDC/TMD forms' internal irregularity diagnoses which are not compatible with MRI diagnoses in the literature.[32,33,34]

When the posttreatment USG diagnosis and RDC/TMD clinical diagnosis were compared for left TMJ, a statistically significant difference was found (κ = 0.256). However, Landis and Koch defined the kappa coefficient, which indicates the degree of compliance, as “compliance below the middle” in the range of 0.21–0.40.[35] As a result of Kappa analysis, compliance below the middle may not be important in clinical applications between 2 diagnostic methods.

The agreement between clinical and imaging-based diagnosis of disc displacement ranges from 59% to 90% of previous studies.[36,37,38] The results of this study are in accordance with previous reports that show such a disparity. Many authors suggest that clinical evaluation does not always allow an accurate assessment of the disc position and its reduction on mouth opening.[37,39,40] According to the present results, such misdiagnosis was most frequent in ADDWR.

Galhardo and his team; evaluated the performance of RDC/TMD in the diagnostic field using MRI as the gold standard. As a result, they showed that there are limitations in the use of RDC/TMD for the diagnosis of articular TMDs as they give false positive results.[32]

That work using the RDC/TMD was performed with a study group of 40 consecutive patients diagnosed with a clinical diagnosis of disc displacement with reduction in at least one TMJ; it described a positive predictive value (PPV) of 56% for disc displacement with reduction, a PPV of 92% for internal derangement, and a preponderance of false-negative errors, especially for asymptomatic TMJs. These findings may indicate that both the clinical diagnostic criteria for TMDs and the RDC/TMD subgroup of disc displacement with reduction are insufficient reliable to predict the MRI diagnoses of a functional disc–condyle relationship.[33,34]

It should be noted that our study was limited in that the follow-up period was only 6 months. Studies with a longer follow-up periods should be planned in future.

CONCLUSION

Within the limitation of the present study, there is no agreement between the diagnosis obtained from dynamic high resolution sonography and clinical diagnose of Axis I of RDC/TMD form.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tvrdy P. Methods of imaging in the diagnosis of temporomandibular joint disorders. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2007;151:133–6. doi: 10.5507/bp.2007.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manfredini D, Guarda-Nardini L. Ultrasonography of the temporomandibular joint: A literature review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;38:1229–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young AL. Internal derangements of the temporomandibular joint: A review of the anatomy, diagnosis, and management.J. Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2015;15:2. doi: 10.4103/0972-4052.156998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pertes RA, Gross SG. Clinical Management of Temporomandibular Disorders and Orofacial Pain. 1st ed. Illinois, Chicago: Quintessence Publishing; 1995. pp. 1–12. 69-89. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cakir-Ozkan N, Sarikaya B, Erkorkmaz U, Aktürk Y. Ultrasonographic evaluation of disc displacement of the temporomandibular joint compared with magnetic resonance imaging. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:1075–80. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jank S, Haase S, Strobl H, Michels H, Häfner R, Missmann M, et al. Sonographic investigation of the temporomandibular joint in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: A pilot study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:213–8. doi: 10.1002/art.22533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Habashi H, Eran A, Blumenfeld I, Gaitini D. Dynamic high-resolution sonography compared to magnetic resonance imaging for diagnosis of temporomandibular joint disk displacement. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;34:75–82. doi: 10.7863/ultra.34.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uysal S, Kansu H, Akhan O, Kansu O. Comparison of ultrasonography with magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of temporomandibular joint internal derangements: A preliminary investigation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94:115–21. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.126026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brandlmaier I, Rudisch A, Bodner G, Bertram S, Emshoff R. Temporomandibular joint internal derangement: Detection with 12.5 MHz ultrasonography. J Oral Rehabil. 2003;30:796–801. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2003.01063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dworkin SF, LeResche L. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: Review, criteria, examinations and specifications, critique. J Craniomandib Disord. 1992;6:301–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schiffman EL, Ohrbach R, Truelove EL, Tai F, Anderson GC, Pan W, et al. The research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders.V: Methods used to establish and validate revised Axis I diagnostic algorithms. J Orofac Pain. 2010;24:63–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.International Consortium for RDC / TMD-based Research. [[Last accessed on 2010 Mar 20]]. Available from: http://rdc-tmdinternationalorg/

- 13.Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E, Look J, Anderson G, Goulet JP, Svensson P, et al. Diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (DC/TMD) for clinical and research applications: Recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. J Oral Facial Pain H. 2014;28:1–6. doi: 10.11607/jop.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bag AK, Gaddikeri S, Singhal A, Hardin S, Tran BD, Medina JA, et al. Imaging of the temporomandibular joint: An update. World J Radiol. 2014;6:567–82. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v6.i8.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kundu H, Basavaraj P, Kote S, Singla A, Singh S. Assessment of TMJ disorders using ultrasonography as a diagnostic tool: A review. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:3116–20. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/6678.3874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emshoff R, Jank S, Bertram S, Rudisch A, Bodner G. Disk displacement of the temporomandibular joint: Sonography versus MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:1557–62. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.6.1781557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klatkiewicz T, Gawriołek K, Pobudek Radzikowska M, Czajka-Jakubowska A. Ultrasonography in the diagnosis of temporomandibular disorders: A meta-analysis. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:812–7. doi: 10.12659/MSM.908810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jank S, Rudisch A, Bodner G, Brandlmaier I, Gerhard S, Emshoff R. High-resolution ultrasonography of the TMJ: Helpful diagnostic approach for patients with TMJ disorders? J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2001;29:366–71. doi: 10.1054/jcms.2001.0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samuel F. Comparing TMD diagnoses and clinical findings at Swedish and US TMD centers using research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Facial Pain H. 1996;10:240–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yap AU, Dworkin SF, Chua EK, List T, Tan KB, Tan HH. Prevalence of temporomandibular disorder subtypes, psychologic distress, and psychosocial dysfunction in Asian patients. J Orofac Pain. 2003;17:21–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shetty R. Prevalence of signs of temporomandibular joint dysfunction in asymptomatic edentulous subjects: A cross-sectional study. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2010;10:96–101. doi: 10.1007/s13191-010-0018-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Randolph CS, Greene CS, Moretti R, Forbes D, Perry HT. Conservative management of temporomandibular disorders: A posttreatment comparison between patients from a university clinic and from private practice. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1990;98:77–82. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(90)70035-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warren MP, Fried JL. Temporomandibular disorders and hormones in women. Cells Tissues Organs. 2001;169:187–92. doi: 10.1159/000047881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greene CS. Temporomandibular disorders in the geriatric population. J Prosthet Dent. 1994;72:507–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(94)90123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mintz S. Craniomandibular dysfunction in children and adolescents: A review. Cranio. 1993;11:224–31. doi: 10.1080/08869634.1993.11677970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Osterberg T, Carlsson GE, Wedel A, Johansson U. Across sectional and longitudinal study of craniomandibular dysfunction in an elderly population. J Craniomandib Disord. 1991;6:237–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Bont LG, Stegenga B. Pathology of temporomandibular joint internal derangement and osteoarthrosis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;22:71–4. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80805-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manfredini D, Ahlberg J, Winocur E, Guarda-Nardini L, Lobbezoo F. Correlation of RDC/TMD axis I diagnoses and axis II pain-related disability.A multicenter study. Clin Oral Investig. 2011;15:749–56. doi: 10.1007/s00784-010-0444-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanefi K, Mumcu E, Muzaffer A. Use of results diagnostic criteria temporomandibular disorders (RDC/TMD) in diagnosis of temporomandibular disorders. J Istanbul Univ Fac Dent. 2012;40:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park JW, Song HH, Roh HS, Kim YK, Lee JY. Correlation between clinical diagnosis based on RDC/TMD and MRI findings of TMJ internal derangement. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41:103–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naeije M, Kalaykova S, Visscher CM, Lobbezoo F. Evaluation of the research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders for the recognition of an anterior disc displacement with reduction. J Oral Facial Pain H. 2009;1:23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galhardo AP, da Costa Leite C, Gebrim EM, Gomes RL, Mukai MK, Yamaguchi CA, et al. The correlation of research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders and magnetic resonance imaging: A study of diagnostic accuracy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;115:277–84. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark GT, Delcanho RE, Goulet JP. The utility and validity of current diagnostic procedures for defining temporomandibular disorder patients. Adv Dent Res. 1993;7:97–112. doi: 10.1177/08959374930070022101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emshoff R, Brandlmaier I, Bösch R, Gerhard S, Rudisch A, Bertram S. Validation of the clinical diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders for the diagnostic subgroup Disc derangement with reduction. J Oral Rehabil. 2002;29:1139–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2002.00980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bertram S, Rudisch A, Innerhofer K, Pümpel E, Grubwieser G, Emshoff R. Diagnosing TMJ internal derangement and osteoarthritis with magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:753–61. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Emshoff R, Rudisch A. Validity of clinical diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: Clinical versus magnetic resonance imaging diagnosis of temporomandibular joint internal derangement and osteoarthrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;91:50–5. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.111129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Emshoff R, Rudisch A, Innerhofer K, Brandlmaier I, Moshen I, Bertram S. Magnetic resonance imaging findings of internal derangement in temporomandibular joints without a clinical diagnosis of temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Rehabil. 2002;29:516–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2002.00883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barclay P, Hollender LG, Maravilla KR, Truelove EL. Comparison of clinical and magnetic resonance imaging diagnosis in patients with disk displacement in the temporomandibular joint. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;88:37–43. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(99)70191-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yatani H, Suzuki K, Kuboki T, Matsuka Y, Maekawa K, Yamashita A. The validity of clinical examination for diagnosing anterior disk displacement without reduction. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;85:654–60. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]