Abstract

Introduction

Emergency physicians frequently provide care for patients who are experiencing viral illnesses and may be asked to provide verification of the patient's illness (a sick note) for time missed from work. Exclusion from work can be a powerful public health measure during epidemics; both legislation and physician advice contribute to patients’ decisions to recover at home.

Methods

We surveyed Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians members to determine what impacts sick notes have on patients and the system, the duration of time off work that physicians recommend, and what training and policies are in place to help providers. Descriptive statistics from the survey are reported.

Results

A total of 182 of 1524 physicians responded to the survey; 51.1% practice in Ontario. 76.4% of physicians write at least one sick note per day, with 4.2% writing 5 or more sick notes per day. Thirteen percentage of physicians charge for a sick note (mean cost $22.50). Patients advised to stay home for a median of 4 days with influenza and 2 days with gastroenteritis and upper respiratory tract infections. 82.8% of physicians believe that most of the time, patients can determine when to return to work. Advice varied widely between respondents. 61% of respondents were unfamiliar with sick leave legislation in their province and only 2% had received formal training about illness verification.

Conclusions

Providing sick notes is a common practice of Canadian Emergency Physicians; return‐to‐work guidance is variable. Improved physician education about public health recommendations and provincial legislation may strengthen physician advice to patients.

Keywords: emergency departments, illness verification, sick notes, viral illness

1. INTRODUCTION

Public health agencies recommend that patients with minor illnesses stay home to recover and to avoid infecting others. 1 Exclusion from work can be a powerful public health measure during outbreaks 2 ; in the US, workplace spread of influenza‐like illness conferred a population‐attributable risk of 5 million additional cases in a study of H1N1 spread during the 2009 epidemic. 3 Emergency physicians frequently see patients with viral infections in the emergency department and are asked to provide guidance about return to work. In some instances, patients may seek medical care solely for the purpose of obtaining a “sick note”, placing unnecessary burden on emergency care providers and systems. 4

In Canada, provincial legislation determines the duration of time that a patient can stay home from work, whether or not an employer can require a sick note, and if patients are paid for sick days. These standards vary significantly between the different provinces and territories. In Ontario, Canada's most populated province, the current legislation provides three unpaid days of job‐protected leave for personal illness, injury, or medical emergency. Employers may ask for a sick note for illness verification, thereby necessitating the employee to seek medical care. During the COVID‐19 pandemic, the legislation has been amended to provide an unspecified number of days of unpaid, job‐protected infectious disease emergency leave. This leave covers isolation, quarantine, and to provide care for family members due to school and day‐care closures. Employers cannot require employees to provide sick notes for the infectious disease emergency leave. 5

Legislation on emergency medical leave and sick notes impact the ability of patients to adhere to physician recommendations. Despite this, little is known about physician knowledge of these standards.

2. OBJECTIVES

We performed a survey of Canadian emergency physicians to determine:

What impacts do “sick notes” for brief illnesses have on patients and the healthcare system?

How long do healthcare providers advise patients to remain off work if they are sick with a brief illness?

What training and/or policies are in place to help healthcare providers issue sick notes?

3. METHODS

Following a literature review, the survey was designed by consensus of four authors, and revised following review by an additional physician and a labor policy expert. The survey was distributed in English only via SurveyMonkey 6 (Appendix 1). The Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP) administered the survey. The link was distributed by email to all CAEP physician members three times in 2‐week intervals between December 2019 and January 2020. Participation in the survey was voluntary and all responses were anonymous.

The survey included multiple‐choice demographic questions, as well multiple‐choice questions and open‐ended, numeric responses to quantify variables such as the duration of time that physicians advise patients to stay home from work, the cost of a sick note, and the frequency with which patients require additional medical care. Participants were allowed to skip questions and data from incomplete surveys were included. Data were analyzed in the R statistical programming language. 7 No financial incentive was provided for participating.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Participant characteristics

Of the 1524 CAEP physician members surveyed, 182 participated. 51.1% reported Ontario as their practice location. 79% practiced emergency medicine exclusively, with the remainder practicing emergency medicine and family medicine, sports medicine, or other specialties.

4.2. Impact on emergency department flow and functioning

The majority (75.1%) of respondents answered that their practice environment does not have a sick note policy in place, or that they were unsure about the policy (10.7% of respondents). Only 13% of emergency providers charge patients for a sick note. The fee charged ranges from $5 to 80 (Canadian dollars), with a mean cost of $22.50. Most physicians provide at least one sick note per day (76.4%), with 4.2% reporting that they provide 5 or more notes per day. 89.7% of respondents believe that patients require additional medical care on half of visits or less.

4.3. Advice to patients

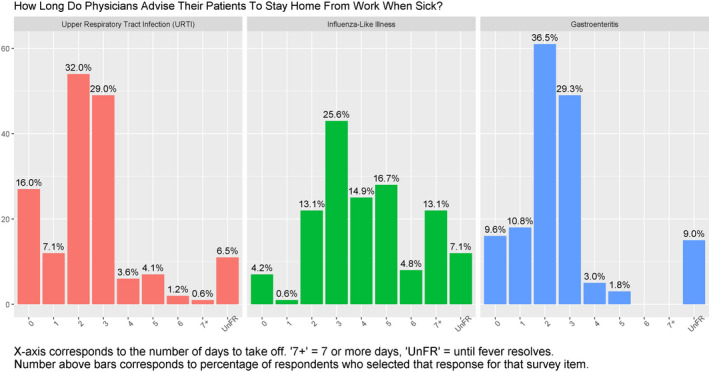

Most respondents answered that they advise patients to remain at home for minor illnesses, however, the duration of exclusion from work varied. For influenza‐like illness, respondents advised patients to remain home from work for a median of 4 days. For an upper respiratory tract infection and for gastroenteritis, respondents advised patients to remain home from work for a median of 2 days. For all conditions, a proportion of respondents did not provide a discrete number of days, rather answered that they advise patients to remain at home until the fever has resolved. The distribution of responses is illustrated in Figure 1. 82.8% of respondents believed that a patient is capable of determining when to return to work “most of the time”, 17.2% believed “sometimes”, and none answered “rarely”.

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of responses of survey participants to the question of how long they advise patients to stay home when sick for three different illnesses. UnFR, until fever resolves; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection

4.4. What knowledge do providers have?

61.2% of participants answered that they were not familiar with the current sick leave legislation in their province, and 18.8% stated that they were unsure. Only 2% of respondents had received training on illness verification during medical school or residency.

5. DISCUSSION

5.1. Interpretation and implications

This survey confirmed our hypothesis that many Emergency Department (ED) physicians are writing sick notes on a daily basis, and that ED providers believe that most of these patients do not require additional care for their viral illness and can safely decide for themselves when to return to work. The CAEP position statement on sick notes recommends that governments prevent employers from requesting sick notes; this study improves our understanding of the frequency with which ED providers are required to see patients for this administrative task. 8

Despite the public health implications, emergency physicians are providing varied advice to patients about exclusion from work while unwell. Increased physician education is needed to ensure that providers are aware of the latest public health recommendations for patients, both during and beyond epidemics. In other conditions, physicians guidance to remain off work is associated with the duration of time used for recovery, however, patients also report receiving advice that they cannot adhere to. 9 In our study, most physicians reported that they were unfamiliar with local sick leave legislation, meaning that providers are unknowingly advising patients to stay home for a period that could, in fact, threaten job and income loss. Physicians require greater knowledge beyond the biomedical paradigm in order to have informed conversations with their patients about return to work. This education could take place in the form of dedicated teaching on occupational health during residency training programs, increased involvement of occupational health specialists in emergency departments, and improved communication of current medical leave policy by policymakers to front‐line health practitioners.

5.2. Limitations

This study included only Canadian emergency physicians, and findings may not be generalizable to primary care settings or in other jurisdictions. Respondents may also represent a biased subset; it is possible that respondents have different sick note provision practices than non‐respondents. This survey did not use a previously validated questionnaire, however, open‐ended questions allowed physicians to provide further clarification to accompany their responses, which was reviewed by the authors. Despite the response rate, we believe that these findings provide an important initial understanding of the current situation in Canada.

6. CONCLUSIONS

Providing sick notes is a common practice of Canadian Emergency Physicians, and may have significant impact on departmental functioning, particularly during viral outbreaks. Advice to patients is variable, and physicians have limited knowledge of governmental policy that impacts sick leave. Improved physician education may be one mechanism to provide better return‐to‐work guidance to patients.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

KH, JM, and HS came up with the idea for this study. KH, JM, HS, and CJV all contributed to survey development and conceptualization of the study. CJV helped with the REB submission. DA did the statistical analysis for this study. KH wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and JM, HS, and CJV edited and revised the manuscript.

DISCLOSURES

Approval of the research protocol: This study received ethics approval from the University of Toronto Health Sciences research ethics board. Informed consent: All participants provided informed consent prior to participating in the survey. Registry and the registration no. of the study/trial: N/A. Animal studies: N/A. Conflict of interests: Carolina Jimenez Vanegas is a paid staff member of the Decent Work and Health Network, which is supported by a grant from the Atkinson Foundation. Drs Hayman, Sheikh, and McLaren are steering committee members of the network and receive no compensation (financial or otherwise) for this activity.

APPENDIX 1.

Health provider attitudes towards illness verification

Your participation in this survey is voluntary. You may withdraw from this study at any time.

Definition of terms

Minor illness or injury

Medical condition that impairs the employee's ability to fully function at work, such as influenza, an upper respiratory tract infection, gastroenteritis, concussion, or severe low back strain. The patient is expected to return to full function after the illness has run its course.

Exclusion

Conditions resulting from workplace injuries are excluded from this survey.

This survey applies to illness verification for workers. Student requests are not included in this survey.

Demographic questions (select all that apply)

-

What kind of medicine do you practice (select all that apply)?

Emergency medicine

Family medicine

Sports medicine

Other subspecialty:

-

What is your level of training or specialization?

Resident

CCFP

CCFP‐EM

FRCPC

Nurse practitioner

-

Where do you practice medicine (select all that apply):

Academic emergency department

Community emergency department – urban

Community emergency department – rural

Office‐based clinic

Urgent Care

What province do you practice in?

(List of all provinces provided)

Questions: please select one answer only

-

Are you familiar with the current sick leave legislation in your province?

Yes

No

Unsure

-

When treating a patient with a viral URTI, do you advise them to stay home from work?

Yes

No

Sometimes

-

If you advise the patient to stay home, how many days do they require off work (on average)?

__________

-

When treating a patient with an influenza‐like illness, do you advise them to stay home from work?

Yes

No

Sometimes

-

If you advise the patient to stay home, how many days do they require off work (on average)?

__________

-

When treating a patient with gastroenteritis, do you advise them to stay home from work?

Yes

No

Unsure

-

If you advise the patient to stay home, how many days do they require off work (on average)?

__________

-

Do physicians/nurses in your practice setting charge patients for sick notes?

Yes

No

Sometimes

-

If so, what is the median cost of a note, in Canadian Dollars?

___________ (Canadian Dollars)

-

Is there a standard medical note policy in your clinic/hospital?

Yes

No

Unsure

-

Do you believe that patients are capable of determining when they are able to return to work?

Most of the time

Sometimes

Rarely

-

How often do patients who request sick notes require additional medical care for diagnosis or treatment? Please enter a percentage estimate (For example, 0% means that patients requesting sick notes never need additional medical care. 100% means that patients always require additional medical care).

___________ (Percentage value from 0 to 100)

-

Approximately how often do you provide a sick note?

Never

Once/week

Once/day

2‐5 notes per day

5‐10 notes/day

>10 notes/day

-

Did you receive training on illness verification during medical/nursing school or residency?

Yes

No

Unsure

Do you have any additional comments? (Open)

Hayman K, McLaren J, Ahuja D, Jimenez Vanegas C, Sheikh H. Emergency physician attitudes towards illness verification (sick notes). J Occup Health. 2021;63:e12195 10.1002/1348-9585.12195

Funding information

This study was supported by a grant from the Atkinson Foundation. The Atkinson Foundation had no input into any component of the study and has not reviewed this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Public Health Agency of Canada . Flu (influenza): symptoms and treatment. 2018 October 19. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public‐health/services/diseases/flu‐influenza.html

- 2. Public Health Agency of Canada . Coronavirus disease (COVID‐19): Being prepared. 2020 March 17. Available from: www.canada.ca/en/public‐health/services/diseases/2019‐novel‐coronavirus‐infection/being‐prepared.html#a5.

- 3. Kumar S, Quinn SC, Kim KH, Daniel LH, Freimuth VS. The impact of workplace policies and other social factors on self‐reported influenza‐like illness incidence during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):134‐140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Canadian Medical Association . Maintaining Ontario’s leadership on prohibiting the use of sick notes. Submission to the standing committee on finance and economic affairs. 2018 Nov 15. Available from https://policybase.cma.ca/documents/Briefpdf/BR2019‐03.pdf

- 5. Ontario Employment Standards Act , 2000, S.O. 2000, c. 41. Available from: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/00e41

- 6. Survey Monkey Inc ., San Mateo, California, USA. Available from: www.surveymonkey.com

- 7. R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. https://www.R‐project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 8. McLaren J, Hayman K, Sheikh H. CAEP position statement on sick notes for minor illness. 17 March 2020. Available from: caep.ca/wp‐content/uploads/2020/03/CAEP‐Sick‐Note‐Position‐Statement‐2020.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9. Guadet LA, Eliyahu L, Beach J, et al. Workers’ recovery from concussions presenting to the emergency department. Occup Med. 2019;69(6):419‐427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]