Abstract

Objective Cultural and health service obstacles affect the quality of pregnancy care that women from vulnerable populations receive. Using a participatory design approach, the Stress in Pregnancy: Improving Results with Interactive Technology group developed specifications for a suite of eHealth applications to improve the quality of perinatal mental health care.

Materials and Methods We established a longitudinal participatory design group consisting of low-income women with a history of antenatal depression, their prenatal providers, mental health specialists, an app developer, and researchers. The group met 20 times over 24 months. Applications were designed using rapid prototyping. Meetings were documented using field notes.

Results and Discussion The group achieved high levels of continuity and engagement. Three apps were developed by the group: an app to support high-risk women after discharge from hospital, a screening tool for depression, and a patient decision aid for supporting treatment choice.

Conclusion Longitudinal participatory design groups are a promising, highly feasible approach to developing technology for underserved populations.

Keywords: patient decision aid, participatory design, depression, pregnancy, low socioeconomic status

BACKGROUND

Disorders of mental health are the leading cause of disability globally 1 and remain underdiagnosed and undertreated. 2 Common mental disorders during pregnancy and the year postpartum (perinatal mental disorders, PMD—most often depression and anxiety) affect 14% to 23% of women overall and as many as 50% of those with low income. They increase the risk of both poor maternal and pediatric outcomes. 3,4 Low-income women and those from minority ethnic groups are simultaneously at greater risk for PMD and less likely to receive care for these disorders. 5,6 These women face a range of both patient- and health services–related obstacles to care. 7

The use of patient-centered eHealth strategies that accommodate end user needs holds promise to overcome a range of care obstacles for this vulnerable population. 8 Participatory methodologies are used to improve the patient centeredness of various interventions. 9 Provider engagement with patients is especially valuable when designing computer-based interventions for vulnerable populations. 10 This can help promote bilateral exchange of knowledge, help address bias and disparities in the development of new interventions, and identify and address obstacles and opportunities among patients and their providers. 11–13

In this paper, we describe an iterative participatory design strategy that resulted in a suite of 3 eHealth tools geared to the particular support needs of low-income, ethnic/racial minority women at risk for PMD. We briefly discuss the apps that were developed and end with recommendations for using this approach.

METHODS

We initiated a participatory design group in January 2013 to address issues surrounding depression in pregnancy called Stress in Pregnancy: Improving Results with Interactive Technology (SPIRIT). The work of this group was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Pennsylvania and focused on the needs of low-income and ethnic minority women in the urban Philadelphia area.

Setting and participants

The SPIRIT group met monthly at a large hospital-based outpatient prenatal care center for low-income, Medicaid-insured women in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. The group comprised members of the 2 key stakeholder groups—women with history of depression in pregnancy and their prenatal providers (nurse practitioners, physicians, social workers, care facilitators, psychologists, and psychiatrists)—as well as center administrators, mental health services researchers, and an application developer (programmer). The center is part of the University of Pennsylvania Health System and cares for approximately 4000 pregnant women annually. More than 90% of the patients seen are US-born African Americans with a high rate of low literacy. 14 An initial information session for all frontline clinical, administrative, and support staff was carried out to recruit staff members. This included obstetrics/gynecology physicians, nurse practitioners, nurses, medical assistants, front desk staff, and mental health providers. The session was announced at a staff meeting and through flyers. Key members of the staff seen as potential champions of the project because of their interest in perinatal depression were approached in person.

Clinicians from the SPIRIT group were asked to identify from their own patient panels potential patient members with a history of perinatal depression and potential interest in participating. Providers invited their patients to come to a SPIRIT meeting to learn about the group.

Process

Participatory design meetings occurred monthly in a waiting area of the prenatal center immediately following the regular workday and lasted 2 hours. From January through June 2013, participants were compensated with $25 for their time. Patients joined the group in March 2013. From July 2013 onwards, compensation was increased to $50 due to increased funding for the project. Participants were also provided with a simple dinner. The group collectively wrote a mission statement, which included the objective of improving communication and healthy outcomes in women with emotional distress using easily accessible interactive technology.

SPIRIT group meetings focused on generating ideas and providing feedback on brief pilot studies implemented by providers, clinical administrative staff, health information technology developers, and video producers. Meetings were facilitated by the research team and involved brainstorming, problem-solving, role-playing, and feedback on content. Role-playing to review impact of the applications on clinical workflow was particularly effective; members of the group were able to observe proposed workflows and provide immediate responses and suggestions for modifications which could then be discussed for issues such as technical feasibility. Patient participants were critical to identifying favored language, features, and stylistic elements of the “look” of the app that were appropriate to the target population. Input on readability and literacy challenges with language used in the app were particularly targeted by these members of the group. The SPIRIT group took a rapid cycle iterative design approach. 11 At each meeting, the SPIRIT group reviewed progress, provided feedback, tested available pilot software, and formulated specific recommendations for immediate next steps. The tools were then revised for the next meeting. Some examples of changes implemented as a result of this process are shown in table 1 .

Table 1.

Examples of changes to design derived from SPIRIT group process—decision aid

| Functionality | Change | Reason for Change |

|---|---|---|

Personified Interface:

|

Addition of animated “guide” to live actor |

|

| Video presentation of content | Break videos into small clips of less than 1 minute |

|

| Navigation | Allow users to skip sections of application |

|

| Content | ||

| Language used | Modification of guide scripts to a more familiar style | Patient team members found initial scripts to be intimidating and unfamiliar |

| Appearance of guides (live actor and animation) |

|

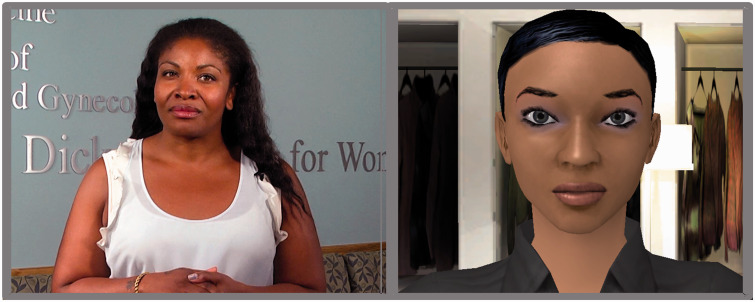

Physical characteristics of the live actor and animation guides were selected based on their appeal to the team members, particularly patients |

| Selection of treatments | Elimination of some treatment options | Treatment options which were not realistically accessible to the target group were eliminated to save user time |

The health care researchers supported the SPIRIT group by organizing and managing the meetings and reviewing literature to gather relevant evidence and content for each of the proposed applications. The researchers also drafted scripts and specifications informed by such considerations as readability and the high rate of limited literacy in the target population. 14 Following lean design principles, the programmer and developer members of the design group were less involved initially until a satisfactory specification was established, after which they developed and presented working prototypes. 11

Live-action videography was carried out on location. Animated “guides” were produced using a commercial software product (Moviestorm; Moviestorm Limited, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Sound for the animation was taken from the live-action video.

RESULTS

Over the course of 24 months, from January 2013 through December 2014, the SPIRIT participatory design team developed 3 applications: the MyGamePlan suicide prevention mobile app for iPhone (Apple Inc, Cupertino, California), a tablet-based screening tool for PMD, and a patient decision aid (PtDA) for supporting treatment decisions for depression in pregnancy by women and their clinicians. The SPIRIT group consisted of a core group of participants ( n = 17) comprising patients with history of depression in pregnancy ( n = 4), prenatal providers ( n = 2), social workers/care managers ( n = 2), mental health specialists ( n = 2), a clinic administrator ( n = 1), support staff ( n = 3), research staff ( n = 2), and a programmer ( n = 1). Average attendance was 13 (range, 5-22 members). Of the initial 17 SPIRIT members, 12 continued for the full development period (71%), while the remaining membership had turnover.

DISCUSSION

MyGamePlan

The SPIRIT group developed a downloadable suicide prevention smartphone application for iPhone called MyGamePlan. This application was designed for use by patients discharged from an inpatient hospitalization for suicide risk. MyGamePlan includes a set of functionalities to support the transition following hospitalization including the following: (1) scheduling and reminder features for follow-up, (2) standard safety plan support, and (3) connections to local resources which take advantage of geo-location capabilities of the mobile device. The design team was expanded for this application to temporarily include (1) a discharge-planning clinical social worker at an inpatient psychiatric center within the same health system, and (2) the parent of a suicide victim with strong interest in advocacy for discharge support.

Depression screening tool

The SPIRIT group developed a tablet-based, self-report screening tool for risk of PMD using a validated 2-stage process with an initial 2-question screen followed by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. 15–17 The screening tool was designed to allow implementation of efficient universal screening for these conditions. The design process included fitting within existing workflow. A series of role-plays were used to work out this process; each step of the screening through risk identification and response by the members of the staff (support staff, prenatal providers, and mental health specialists) was reviewed during SPIRIT meetings with immediate feedback by team members and corrections to design. The final process involved initial identification of eligible patients (following standard recommendations 3 times over the course of pregnancy and postpartum) during appointment check-in. Patient responses are linked to a patient’s unique office visit using a visit bar code generated by scheduling software used in the center. Patients take the tablet computer to their seats to complete questions in privacy before seeing a clinician. The screening includes validated strategies designed to reduce the burden and increases the efficiency of the process. 15 A provisional diagnosis based on these answers is provided for use by clinicians. 16,17 These results are immediately transmitted wirelessly through a secure hospital Wi-Fi network to the electronic health record accessible to health care providers for use in that visit. Patients with current self-harm risk are flagged for immediate assessment of risk severity.

Technology to improve patient services, a tablet-based patient decision aid

The most ambitious of the apps developed by SPIRIT was a PtDA to help women with perinatal depression learn about and discuss different treatment modalities with their providers. 18 Patient and provider education about available choices is critical to engaging and monitoring women at risk for PMD, where choices are strongly influenced by patient preference. The group’s design work was guided by the Ottawa Decision Support Framework and International Patient Decision Aids Standards ( figure 1 ): (1) assess client and practitioner determinants of decisions to identify decision support needs, (2) provide decision support tailored to client needs, and (3) evaluate the decision making process and outcomes. 18,19 The group identified a set of key features for the electronic PtDA ( table 2 ). Guiding design principles included accommodating patient preferences, clinical usefulness, cultural appropriateness, and accessibility to women with low literacy. 19 The group went on to evaluate depression treatment options for inclusion in the decision aid. Four criteria were identified by the group and used to select and describe treatment options: evidence of benefit, evidence of harm, ease of use, and availability to the patient population. The final set of treatments is listed in table 3 .

Figure 1:

Ottawa Decision Support Framework TIPS, Technology to Improve Patient Services.

Table 2.

Features of TIPS patient decision aid.

| Feature |

|---|

| General |

| Audio-video |

| Interactive design |

| Patient decision aid a |

| Psychoeducation |

| Values clarification |

| Stratified presentation of options |

| Review of options |

| Patient-selected preferences |

| Clinical needs of center |

| Screening tool for risk of depression |

| Clinical summary |

| Provider decision support |

| Inclusion in electronic medical record |

a International Patient Decision Aids Standards components. 16

Table 3.

Treatments covered in the TIPS tablet-based patient decision aid

| Treatment |

| Antidepressant medications |

| Psychotherapeutic counseling |

| Watchful waiting |

| Bright light therapy |

| Exercise |

| Behavioral activation |

| Massage therapy |

| Relaxation therapy |

| Music therapy |

PtDA functionalities

Technology to Improve Patient Services (TIPS) is a mobile, tablet-based application developed for patient use in the waiting room. Some examples of the role that the SPIRIT group had in the design of this application are shown in table 3 . The SPIRIT group selected a tablet as the medium for the PtDA for (1) ease of use in the waiting room before appointments, (2) patient familiarity with mobile devices, and (3) ability to integrate audio and visual components for low-literacy users. A personified interface “guide” approach was chosen—both a live actor and an animated guide were used to enhance engagement with the application process (see figure 2 ). SPIRIT group members felt that the animated option provided an alternative that would be appealing to a substantial portion of users. The actual utilization and preferences of these options will be formally assessed in future evaluation work.

Figure 2:

Selected Characters for TIPS-personified Interface.

The final design of the TIPS app is shown in figure 3 . Patients screening positive for risk of depression are directed to the PtDA. An introductory video allows navigator selection. Patients are then taken through a series of content and question sections that include (1) psychoeducation—introducing patients to depression in pregnancy, and (2) values clarification—where users review preferences regarding features of potential treatments such as safety and efficacy in the context of pregnancy. Results of the depression screening sections determine initial treatment recommendations for patients based on treatment guidelines. 20 The algorithm used to generate this list incorporates severity of depression symptoms and the presence of thoughts of self-harm. All 9 of the treatments are available as icons on the screen of the tablet. The navigator describes each treatment, the evidence of benefit and harm, and ease of use.

Figure 3:

TIPS App Schematic TIPS, Technology to Improve Patient Services.

A patient ultimately selects specific treatment preferences that she wishes to discuss with her prenatal care providers. This information is summarized along with screening results and the values clarification summary for the patient (in paper form) as well as her prenatal provider (electronically through the electronic medical record). Prenatal providers are given additional brief clinical decision support so that they are prepared to discuss and initiate a plan.

In order to balance the need for rapid viewing of videos and potential need for updates of content, the TIPS PtDA utilizes a hybrid app design with a web-based element but with preloaded videos on the tablet devices for viewing. Content will be updated based on new findings as part of the management of the app.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Multistakeholder participatory design groups are an effective way of developing patient-centered, eHealth solutions for low-income and racial/ethnic minority populations. Since such groups take time to establish, we recommend budgeting adequate time and resources to develop applications. Champions from a range of stakeholder groups played a large role in successfully establishing the group. By recruiting patients from the caseload of providers already involved in SPIRIT, we ensured that there already was an established trust between end users and provider stakeholders.

CONTRIBUTORS

All of the authors of this work have made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the analysis or interpretation of data for the work; drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published. All authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

COMPETING INTERESTS

None.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant No. 1 K18 HS022441-01 and the Penn Medicine Center for Innovations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors prepared the current manuscript for the SPIRIT group. Ms. Gordon was supported by a grant from the FOCUS Fellowship on Women’s Health of the Perelman School of Medicine of the University of Pennsylvania.

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization . The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 update . Geneva, Switzerland: : WHO; ; 2008. . [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jiang HJ, Elixhauser A, Nicholas J, et al. . Care of Women in U.S. Hospitals . Vol. 2 . Rockville, MD: : Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; ; 2000. . [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chung TK, Lau TK, Yip AS, et al. . Antepartum depressive symptomatology is associated with adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes . Psychosomatic Med 2001. ; 63 ( 5 ): 830 – 4 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gaynes B, Gavin N, Meltzer-Brody S, et al. . Perinatal Depression: Prevalence, Screening Accuracy, and Screening Outcomes: Summary . Rockville, MD: : Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; ; 2005. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chabrol H, Teissedre F, Saint-Jean M, et al. . Prevention and treatment of post-partum depression: a controlled randomized study on women at risk . Psychol Med 2002. ; 32 ( 6 ): 1039 – 47 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cooper PJ, Murray L, Wilson A, et al. . Controlled trial of the short- and long-term effect of psychological treatment of post-partum depression . Brit J Psychiatr 2003. ; 182 : 412 – 9 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shakespeare J, Blake F, Garcia J . A qualitative study of the acceptability of routine screening of postnatal women using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale . Br J Gen Pract 2003. ; 53 ( 493 ): 614 – 9 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Agarwal S, Labrique A . Newborn health on the line the potential mHealth applications . JAMA 2014. ; 312 ( 3 ): 229 – 30 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jones L, Wells K . Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research . JAMA 2007. ; 297 ( 4 ): 407 – 10 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chang BL, Bakken S, Brown SS, et al. . Bridging the digital divide: reaching vulnerable populations . J Am Inform Assoc 2004. ; 11 ( 6 ): 448 – 57 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bodker K, Kensing F, Simonsen J . Participatory IT Design; Designing for Business and Workplace Realities . Cambridge, MA: : The MIT Press; ; 2004. . [Google Scholar]

- 12. van Bruinessen IR, van Weel-Baumgarten EM, Snippe HW, et al. . Active patient participation in the development of an online intervention . J Med Internet Res 2014. ; 16 ( 11 ). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Luxton DD, McCann RA, Bush NE, et al. . mHealth for mental health: integrating smartphone technology in behavioral healthcare . Prof Psychol Res Pract 2011. ; 42 ( 6 ): 505 – 12 . [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bennett I, Switzer J, Aguirre A, et al. . ‘Breaking it down': patient-clinician communication and prenatal care among African American women of low and higher literacy . Ann Fam Med 2006. ; 4 : 334 – 40 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bennett IM, Coco A, Coyne JC, et al. . Efficiency of a two-item pre-screen to reduce the burden of depression screening in pregnancy and postpartum: an IMPLICIT network study . J Amer B Fam Med 2008. ; 21 ( 4 ): 317 – 25 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, et al. . Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many . J Gen Int Med 1997. ; 12 : 439––45. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW . The PHQ-9—Validity of a brief depression severity measure . J Gen Int Med 2001. ; 16 : 606––13. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Volk RJ, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Stacey D, et al. . Ten years of the International Patient Decision Aid Standards Collaboration: evolution of the core dimensions for assessing the quality of patient decision aids . BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013. ; 13.(2): S1 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Légaré F, O'Connor AC, Graham I, et al. . Supporting patients facing difficult health care decisions: use of the Ottawa Decision Support Framework . 2006. . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yonkers KA, Wisner KL, Stewart DE, et al. . The management of depression during pregnancy: a report from the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . Gen Hosp Psychiatr 2009. ; 31 ( 5 ): 403 – 13 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]