Abstract

In contrast to most Burkholderia species, which affect humans or animals, Burkholderia glumae is a bacterial pathogen of plants that causes panicle blight disease in rice seedlings, resulting in serious damage to rice cultivation. Attempts to combat this disease would benefit from research involving a phage known to attack this type of bacterium. Some Burkholderia phages have been isolated from soil or bacterial species in the order Burkholderiales, but so far there has been no report of a complete genome nucleotide sequence of a phage of B. glumae. In this study, a novel phage, FLC5, of the phytopathogen B. glumae was isolated from leaf compost, and its complete genome nucleotide sequence was determined. The genome consists of a 32,090-bp circular DNA element and exhibits a phylogenetic relationship to members of the genus Peduovirus, with closest similarity to B. multivorans phage KS14. In addition to B. glumae, FLC5 was also able to lyse B. plantarii, a pathogen causing rice bacterial damping-off disease. This is the first report of isolation of a P2-like phage from phytopathogenic Burkholderia, determination of its complete genomic sequence, and the finding of its potential to infect two Burkholderia species: B. glumae and B. plantarii.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00705-020-04811-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Burkholderia is the type genus of family Burkholderiaceae, which, together with a number of ecologically diverse organisms, comprises the order Burkholderiales, class Betaproteobacteria. The order Burkholderiales includes 10 other genera in addition to Burkholderia [1] and includes truly environmental saprophytic organisms, phytopathogens, and opportunistic pathogens that infect humans and animals. Bacteriophages are also widespread in the biosphere and probably have an important influence on the evolution, diversity, and ecology of environmental bacteria [2–4].

So far, 37 complete genome sequences of Burkholderia phages have been registered in the NCBI genome database [1, 5–8], isolated from Burkholderia cepacia (an opportunistic human pathogen that most often causes pneumonia), B. cenocepacia (another opportunistic pathogen causing infections in patients with cystic fibrosis and chronic granulomatous disease), B. pseudomallei (causing melioidosis), and B. thailandensis (closely related to B. pseudomallei). Also, related prophage islands, diversified and modulated, have been identified in Burkholderia genomes [9–12].

Concerning the phytopathogenic species B. glumae, which causes panicle blight and seedling rot diseases, thereby reducing rice yield [13, 14], the whole genome sequences of seven strains of B. glumae (BGR1, PG1, LMG2196, AU6208, 3252-8, 336gr-1, and NCPPB3923) have been registered in the NCBI genome database [15] and shown to contain B. glumae prophage DNA [16, 17]. In addition, B. glumae phages have been isolated from river or puddle water [18]. However, to date, there is no complete genome DNA sequence of a B. glumae phage. Therefore, efforts were made to isolate B. glumae phages from leaf compost. This is the first report of the complete genome nucleotide sequence of a P2-like phage that lyses two plant-pathogenic Burkholderia species: B. glumae and B. plantarii.

The phage particle isolation procedure is described in the Electronic Supplementary Materials. Electron microscopy of the phage particle showed that it consists of an icosahedral capsid with a contractile tail (Fig. S1B). Tailed phages belong to the families Myoviridae, Podoviridae or Siphoviridae in the order Caudovirales, contain double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), and represent the most numerous, the most widely distributed, and probably the oldest group of bacteriophages [19, 20].

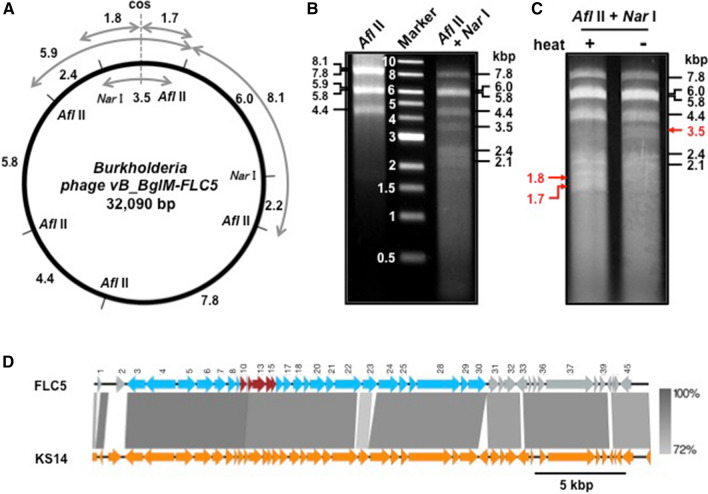

Isolation of phage DNA, construction of the phage DNA library, DNA sequencing and data analysis are described in the Electronic Supplementary Materials. The genome of the Burkholderia phage consisted of a 32,090-bp circular dsDNA molecule (Fig. 1A). The restriction enzyme digestion patterns obtained after cutting the circular genomic DNA with Afl II or Nar I were in agreement with the restriction map predicted from the nucleotide sequence (Fig. 1A and B). A cohesive end site required for termination of packaging of the phage chromosome is labeled as “cos” in Fig. 1A. Detection of 1.7- and 1.8-kbp DNA fragments, which seem to be generated from a 3.5-kbp DNA fragment by treatment at 80 °C for 15 min (Fig. 1C), and alignment of core nucleotide sequence including cos (Fig. S2) suggested that the cos sequence is present in the genome of the Burkholderia phage. The genome nucleotide sequence has been submitted to the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ database with accession number LC528882, in which the terminal nucleotide of the cos site is oriented as + 1 (Fig. S2).

Fig. 1.

Genomic structure of Burkholderia phage vB_BglPM-FLC5. A. Schematic representation of the genomic DNA, showing cleavage sites for AflII and NarI. Numbers represent the size of fragments in nucleotide base pairs (kbp) created by digestion with AflII and/or NarI. B. Electrophoretic analysis of genomic DNA of FLC5 digested with AflII (left lane) or AflII and NarI (right lane). Center lane: DNA ladder size marker. C. Electrophoretic analysis of genomic DNA of FLC5 digested with AflII and NarI, followed by heating at 80 °C for 15 min (heat +) and then chilling on ice for 5 min. As a control, AflII and NarI-digested FLC5 DNA was not treated at 80 °C (heat -). A cohesive end site required for termination of packaging of the phage chromosome is labeled as “cos”. 1.7- and 1.8-kbp DNA fragments, which appear to have been generated from an unheated 3.5-kbp DNA fragment containing “cos” by heat treatment, are indicated by red arrows. D. Functional gene map and comparative genomic analysis of Burkholderia phage FLC5 of B. glumae and KS14 of B. multivorans. Red arrows represent the host lysis module; light blue arrows represent the phage structure and packaging module; and gray arrows represent genes encoding the DNA partitioning protein, zinc finger CHC2-family transcription factor, repressor protein, serine recombinase and hypothetical proteins

Nucleotide sequence comparisons, using BLASTn revealed 92% identity (query coverage, 89%) to the complete DNA genome sequence of Burkholderia phage KS14, which was isolated from an extract of Dracaena sp. soil plated on B. multivorans C5393 [21] and belongs to the family Myoviridae, subfamily Peduovirinae, genus Peduovirus. Thus, the purified phage was assigned the name "Burkholderia phage vB_BglM-FLC5", derived from ʻa virus of Bacteria, infecting Burkholderia glumae, with Myoviridae morphologyʼ, and the strain was designated "FLC5".

Open reading frames (ORFs) encoding gene products gp1 to 45 were identified and assigned to the FLC5 genome DNA by the method described in the Electronic Supplementary Materials (Fig. 1D and Table S1). The functions of proteins encoded by the FLC5 genome were predicted by homology searches using BLASTp. ORFs 10 to 15 encode a host lysis module, and a phage structure and packaging module is encoded by ORFs 3–9 and 16–30, respectively (Fig. 1D and Table S1). Serine recombinase, repressor protein, zinc finger CHC2-family transcription factor, and a DNA partitioning protein are encoded by ORFs 33, 34, 38 and 45, respectively (Fig. 1D and Table S1).

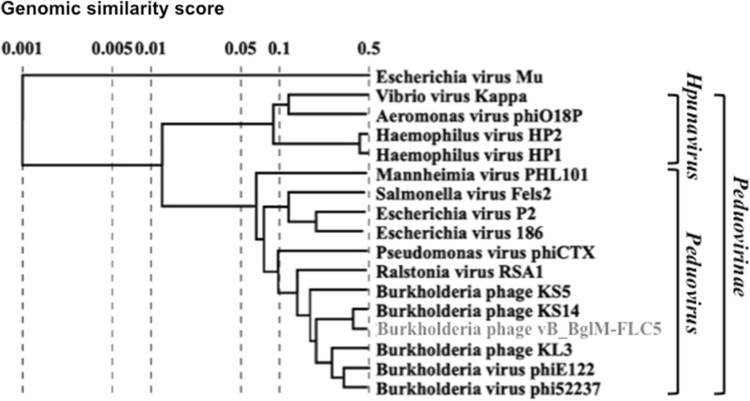

A multiple sequence alignment was performed of the genome sequence of Burkholderia phage FLC5 and those of 16 other Myoviridae members. The latter included 11 Peduovirus phages and four Hpunavirus phages, forming the in-group compared against Muvirus phage Mu of Escherichia. The analysis revealed the highest sequence identity of FLC5 to phage KS14 of B. multivorans (i.e., Burkholderia phage KS14) and, accordingly, the closest relationship in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2). Considering that Burkholderia phage KS14, which is the closest relative of FLC5, is a temperate phage [22], FLC5 may not be obligately lytic but temperate. It is also possible that FLC5 may be a mutant lacking ability to lysogenize.

Fig. 2.

Whole-genome phylogenetic tree of Burkholderia phage FLC5 and 15 members of the subfamily Peduovirinae, including 11 members of the genus Peduovirus, four members of the genus Hpunavirus, and one member of the genus Muvirus (phage Mu of Escherichia) generated using ViPTree v1.9 [8]

Upon PCR analysis of genomic DNA from B. glumae MAFF302746 using primers specific for phage FLC5 (see Methodology in Electronic Supplementary Materials), no amplified DNA products were obtained, whereas the 16S rDNA fragment of B. glumae MAFF302746, which was used for isolation of FLC5 in our experiment, was detected by PCR using primers specific for 16S rDNA (Fig. S3). This indicated that FLC5 was not derived from prophage sequences in the B. glumae MAFF302746 genome but instead from a Burkholderia phage collected from leaf compost.

Rice panicle blight and seedling rot caused by B. glumae and rice bacterial damping-off and seedling blight caused by B. plantarii are major bacterial diseases affecting rice nursery seedling cultivation [13, 14, 23]. To survey the host range of Burkholderia phage FLC5, the susceptibility of five isolates of B. glumae and six isolates of B. plantarii was examined. Three isolates of B. glumae (MAFF302746, MAFF301169 and MAFF302417) and one isolate of B. plantarii (MAFF302475) were lysed by Burkholderia phage FLC5 (Table S2), demonstrating that it has the potential to control two major bacterial diseases of rice nursery seedling cultivation.

Nucleotide sequence accession number The GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ accession number for Burkholderia phage vB_BglM-FLC5 is LC528882.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by grants for “Scientific Research on Innovative Areas” from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Science, Sports and Technology (MEXT), Japan (grant numbers 16H06429, 16K21723, and 16H06435), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) and (C) (grant numbers 19H02953 and 20K06045), Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research (grant number 19K22300) and by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) through the JSPS Core-to-Core Program (Advanced Research Networks) entitled “Establishment of international agricultural immunology research-core for a quantum improvement in food safety”. We thank the Human Genome Center at the University of Tokyo for allowing us to use their supercomputer, and GeneBank (NARO, Tsukuba, Japan) for supplying B. glumae.

Author contributions

HT conceived the study; RS, KI and SA conducted the experiments; RS and SM analyzed the data; RS, SM, SA, TF, RK, and HT interpreted the results. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript for publication.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Coenye T. The Family Burkholderiaceae. In: Rosenberg E, DeLong EF, Lory S, Stackebrandt E, Thompson F, editors. The Prokaryotes. Chapter 28. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2013. pp. 759–776. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamilton G. Virology: the gene weavers. Nature. 2006;441:683–685. doi: 10.1038/441683a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suttle CA. Marine viruses-major players in the global ecosystem. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:801–812. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas CM. Mechanisms of, and barriers to, horizontal gene transfer between bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:711–721. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gill JJ, Young R. Therapeutic applications of phage biology: history, practice and recommendations. In: Miller AA, Miller PF, editors. emerging trends in antibacterial discovery: answering the call to arms. Norfolk, Caister: Academic Press; 2011. pp. 367–410. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lynch KH, Dennis JJ. Genomics of Burkholderia phages. In: Coenye T, Mahenthiralingam E, editors. Burkholderia, from genomes to function. Norfolk, Caister: Academic Press; 2014. pp. 221–250. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Semler DD, Lynch KH, Dennis JJ. The promise of bacteriophage therapy for Burkholderia cepacia complex respiratory infections. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;1:27. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2011.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Summer EJ, Gill JJ, Upton C, Gonzalez CF, Young R. Role of phages in the pathogenesis of Burkholderia, or “where are the toxin genes in Burkholderia phages?”. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2007;10:410–417. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chain PSG, Denef VJ, Konstantinidis KT, et al. Burkholderia xenovorans LB400 harbors a multi-replicon, 9.73-Mbp genome shaped for versatility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15280–15287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606924103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holden MTG, Titball RW, et al. Genomic plasticity of the causative agent of melioidosis, Burkholderia pseudomallei. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14240–14245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403302101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holden MTG, Seth-Smith HMB et al (2009) The genome of Burkholderia cenocepacia J2315, an epidemic pathogen of cystic fibrosis patients. J Bacteriol 191:261–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Yu Y, Kim HS, et al. Genomic patterns of pathogen evolution revealed by comparison of Burkholderia pseudomallei, the causative agent of melioidosis, to avirulent Burkholderia thailandensis. BMC Microbiol. 2006;6:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-6-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ham JH, Melanson RA, Rush MC. Burkholderia glumae: next major pathogen of rice? Mol Plant Pathol. 2011;12:329–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2010.00676.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uematsu T, Yoshimura D, Nishiyama K, Ibaraki T, Fujii H. Occurrence of bacterial seedling rot in nursery flat, caused by grain rot bacterium Pseudomonas glumae. Ann Phytopathol Soc Jpn. 1976;42:310–312. doi: 10.3186/jjphytopath.42.310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee H-H, Park J, Kim J, Park I, Seo YS. Understanding the direction of evolution in Burkholderia glumae through comparative genomics. Curr Genet. 2016;62:115–123. doi: 10.1007/s00294-015-0523-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Francis F, Kim J, Ramaraj T, Farmer A, Milton C, Rush MC, Ham JH. Comparative genomic analysis of two Burkholderia glumae strains from different geographic origins reveals a high degree of plasticity in genome structure associated with genomic islands. Mol Genet Genom. 2013;288:195–203. doi: 10.1007/s00438-013-0744-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim JY, Lee T-H, Nahm BH, Choi YD, Kim M, Hwang I. Complete genome sequence of Burkholderia glumae BGR1. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:3758–3759. doi: 10.1128/JB.00349-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adachi N, Tsukamoto S, Inoue Y, Azegami K. Control of bacterial seedling rot and seedling blight of rice by bacteriophage. Plant Dis. 2012;96:1033–1036. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-03-11-0232-RE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hendrix RW, Smith MC, Burns RN, Ford ME, Hatfull GF. Evolutionary relationships among diverse bacteriophages and prophages: all the world's a phage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2192–2197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ackermann H-W. Bacteriophage taxonomy. Microbiol Aust. 2011;32:90–94. doi: 10.1071/MA11090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seed KD, Dennis JJ. Experimental bacteriophage therapy increases survival of Galleria mellonella larvae infected with clinically relevant strains of the Burkholderia cepacia complex. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:2205–2208. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01166-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lynch KH, Stothard P, Dennis JJ. Genomic analysis and relatedness of P2-like phages of the Burkholderia cepacia complex. BMC Genom. 2010;11:599. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azegami K, Nishiyama K, Watanabe Y, Kadota I, Ohuchi A, Fukuzawa C. Pseudomonas plantarii, sp. nov., the causal agent of rice seedling blight. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1987;37:144–152. doi: 10.1099/00207713-37-2-144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.