Abstract

Introduction

This case report details the surgical treatment of an RA patient who presented with concomitant AAI and subaxial spondylotic stenosis and was subsequently treated via a C1–2 screw–rod construct, semispinalis cervicis sparing C3 laminectomy, and C4–C7 laminoplasty. Our case report is the first to describe a surgical approach for treatment of concomitant AAI and subaxial spondylotic stenosis in a patient with RA.

Case presentation

A 66-year-old male with a history of rheumatoid arthritis and atlantoaxial instability presented to an outpatient spine clinic with complaints of neck pain and worsening gait imbalance. A flexion–extension MRI revealed compression of the posterior aspect of the C1 ring on the back of the spinal cord during flexion, resulting in cord deformation; subaxial spondylosis with moderate associated stenosis and congenital narrowing from C3–7; and central cord compression with T2 signal change at C5–6. A C1–2 arthrodesis was performed and the subaxial spinal cord was then decompressed by performing a seminspinalis-sparing C3 laminectomy, C4–6 laminoplasties, and C7 dome laminectomy. Follow-up flexion–extension radiographs demonstrated satisfactory hardware position at C1–2 and full range of motion at C3–7.

Discussion

This is the first study to describe the surgical management of an RA patient with concomitant AAS and subaxial spondylotic stenosis. Patients with these simultaneous pathologies can be considered for decompression caudal to the C1–2 arthrodesis, though they should be adequately counseled regarding the risk of developing SAS requiring subsequent fusion.

Subject terms: Bone, Outcomes research

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disease that has a worldwide prevalence in the adult population of 1–2% [1]. After the small peripheral joints of the extremities, the cervical spine is the second most commonly involved region of the body, and its involvement is associated with an increase in morbidity and mortality [2–4]. Changes in the cervical spine secondary to RA are progressive in nature [5–8], resulting in a characteristic cascading pattern of instability that begins with atlantoaxial instability (AAI) [9–13], followed by subsequent development of vertical subluxation (VS) of the axis [14, 15], and subaxial subluxation (SAS) [16]. Cervical spine involvement in RA is of particular import due to the significantly increased risk of myelopathy, vertebrobasilar insufficiency, and sudden death, particularly when VS and SAS are present [6, 16–18]. Timely surgical intervention is critical to prevent worsening instability and neurologic compromise [19, 20].

A vast body of literature exists investigating the surgical treatment of cervical instability in RA patients. For RA patients with AAI, a variety of surgical treatment options exist [21–28], all with the ultimate goal of fusing the C1–2 segment. When SAS is present, the goal of surgical intervention is to decompress the spinal cord to prevent the progression of myelopathy while fusing the spine to prevent further subluxation; here again, multiple techniques have been described [29–37]. On the other hand, subaxial spondylotic stenosis, which lacks the hypermobile segmental subluxation seen in SAS, is commonly treated with an isolated motion-sparing decompression. Therefore, in patients with RA it is critical to differentiate the underlying pathogenesis of their subaxial stenosis in order to guide subsequent surgical intervention. To our knowledge, there are no studies in the current literature that investigate the combined surgical treatment of concomitant AAI and subaxial spondylotic stenosis in patients with RA. This case report details the surgical treatment of an RA patient who presented with concomitant AAI and subaxial spondylotic stenosis and was subsequently treated via a C1–2 screw–rod construct, semispinalis cervicis (SSC) sparing C3 laminectomy, and C4–C7 laminoplasty. Our case report is the first to describe a surgical approach for treatment of concomitant AAI and subaxial spondylotic stenosis in a patient with RA.

Case presentation

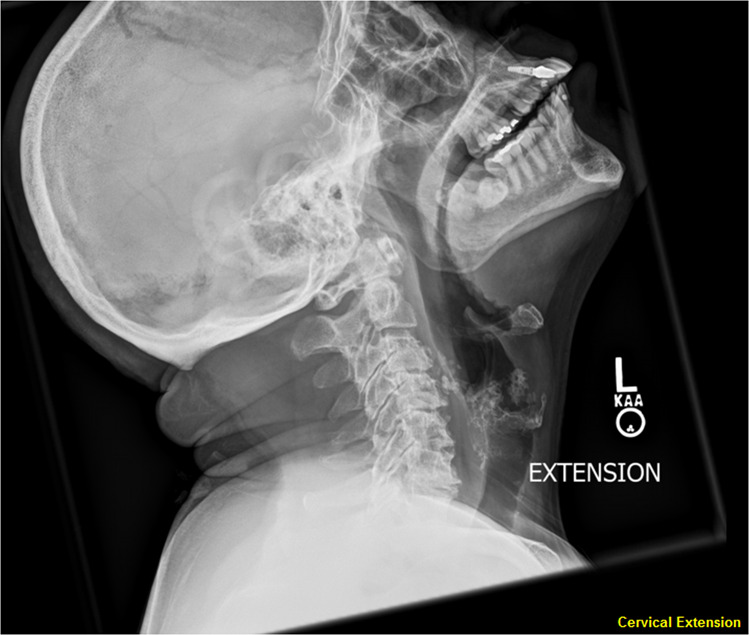

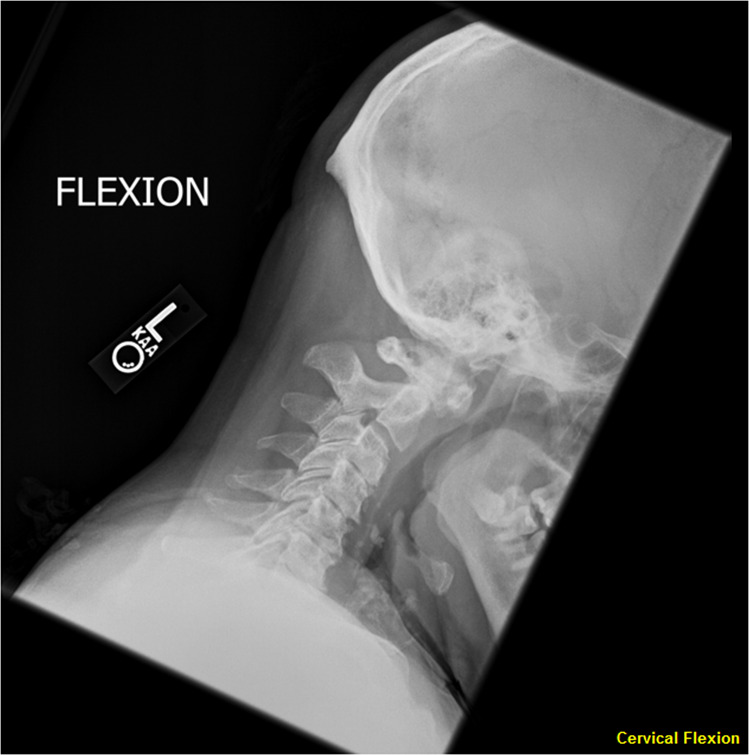

A 66-year-old male with a history of RA and AAI presented to an outpatient spine clinic with complaints of neck pain and worsening gait imbalance. He reported a Neck Disability Index (NDI) of 26% and a Visual Analog Score (VAS) of 3/10. Previous treatment for his RA included long-term pharmacologic treatment with Adalimumab (Humira, AbbVie Inc., North Chicago, Illinois, USA) and Methotrexate [38, 39]. On physical examination, the patient was noted to have bilateral 4-/5 intrinsic hand weakness, positive Hoffman’s sign bilaterally, patellar hyperreflexia, and gross instability on tandem gait evaluation. Review of the patient’s flexion–extension X rays demonstrated 7.5 mm of C1–2 instability (Figs. 1, 2). Due to the patient’s signs of myelopathy and radiographs demonstrating AAI, a flexion–extension MRI was performed and revealed compression of the posterior aspect of the C1 ring on the back of the spinal cord during flexion, resulting in cord deformation; subaxial spondylosis with moderate associated stenosis and congenital narrowing from C3–7; central cord compression with T2 signal change at C5–6; and moderate bilateral foraminal stenosis at C3–4, C4–5, C5–6, and C6–7 (Figs. 3, 4). Due to the foraminal stenosis present on the MRI, an EMG was obtained and demonstrated chronic bilateral C5–8 radiculopathies without evidence of uncompensated denervation. A CT of the cervical spine and CT angiogram were obtained for preoperative planning purposes. After a thorough discussion of treatment options, the patient opted to pursue surgical stabilization via a C1–2 arthrodesis with C3 laminectomy and C4–7 laminoplasty.

Fig. 1. Preoperative cervical radiograph.

Preoperative cervical extension radiograph demonstrating atlantoaxial instability.

Fig. 2. Preoperative cervical radiograph.

Preoperative cervical flexion radiograph demonstrating atlantoaxial instability.

Fig. 3. Preoperative cervical MRI.

Sagittal cut of cervical spine T2 MRI in extension demonstrating atlantoaxial instability.

Fig. 4. Preoperative cervical MRI.

Sagittal cut of cervical spine T2 MRI in flexion demonstrating atlantoaxial instability.

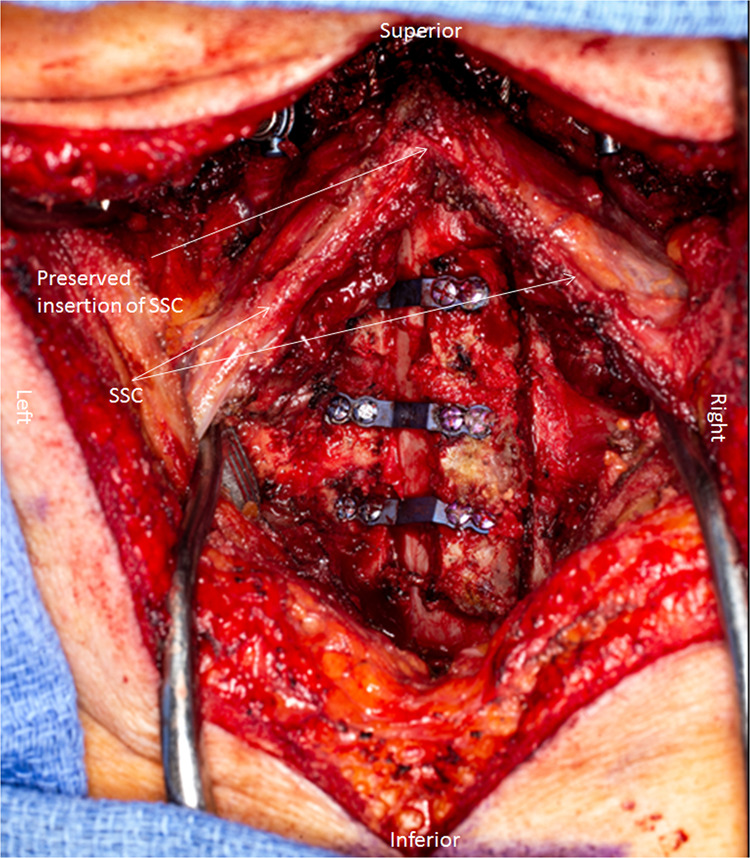

After completion of a pre-anesthesia medical evaluation and temporary discontinuation of the patient’s Humira and Methotrexate, the patient was brought to the operating theater. He was positioned prone and placed in bivector traction to keep the neck in a neutral position. Following midline superficial dissection, exposure was performed of the entirety of C1, the cranial aspect of C2, and the C3–6 laminae in their entirety while preserving the bilateral facet capsules. Special attention was paid to preserving the SSC along its course and at its insertion in the C2 spinous process (Figs. 5, 6). C1–2 arthrodesis was performed via C1 lateral mass and C2 pars screws with autologous iliac crest bone graft and sublaminar cabling using a modified Dickman technique. The subaxial spinal cord was then decompressed by performing a C3 laminectomy, C4–6 laminoplasties, and C7 dome laminectomy. The patient tolerated the procedure without intraoperative complications.

Fig. 5. Intraoperative photograph posterior cervical spine.

Intraoperative photograph demonstrating sparing of the insertion of the semispinalis cervicis in the C2 spinous process.

Fig. 6. Intraoperative photograph posterior cervical spine.

Intraoperative photograph demonstrating sparing of the insertion of the semispinalis cervicis in the C2 spinous process.

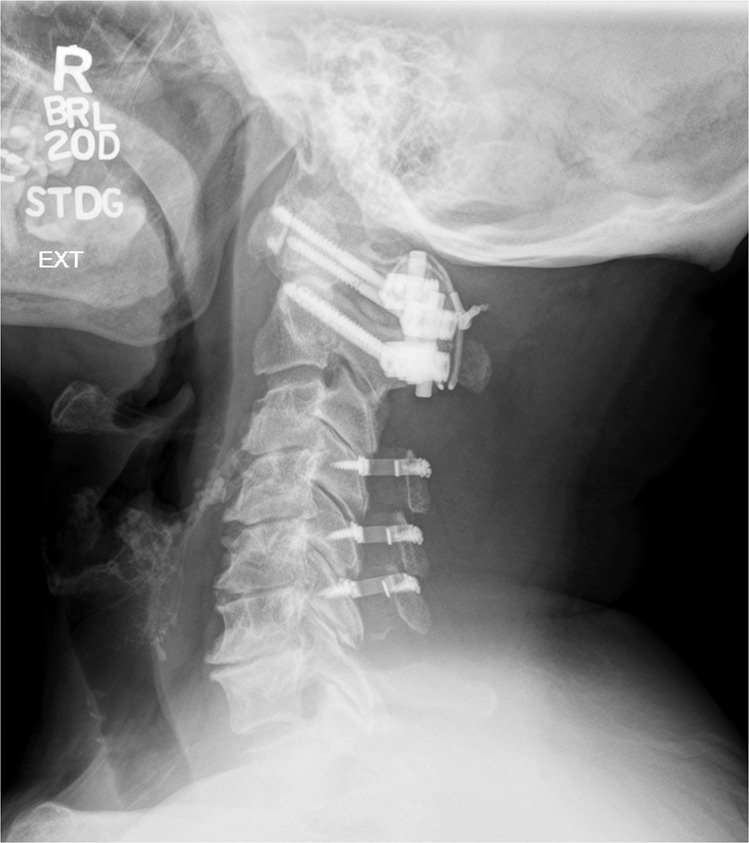

Postoperatively, the patient was transferred to the general care floor in stable condition. The patient had an uneventful hospital course and was discharged home on postoperative day 2. At his 3-month follow-up appointment, the patient reported significantly improved gait balance, motor strength, and neck pain. He reported a NDI of 28% and VAS of 1/10. Physical examination demonstrated full strength in bilateral upper and lower extremities other than improved residual 4+/5 weakness in the intrinsic musculature of bilateral hands. His postoperative flexion–extension radiographs demonstrated satisfactory hardware position at C1–2 without signs of instability and full range of motion at C3–7 at 3-month follow-up (Figs. 7, 8, 9). At his 6-month follow-up appointment, the patient continued to report an improvement in his preoperative symptoms with an NDI of 26% and occasional pain rated as a VAS of 2/10. On examination, he demonstrated improved strength in bilateral hand intrinsics with stable, persistently poor tandem gait. A full cervical spine X-ray series including AP, lateral, extension, and flexion radiographs demonstrated appropriate hardware position at C1–2 without signs of dynamic instability and full range of motion at C3–7 (Figs. 10, 11, 12). The patient’s postoperative course has remained uncomplicated.

Fig. 7. Postoperative cervical radiograph.

Lateral radiograph of the fusion construct at the 3-month follow-up appointment.

Fig. 8. Postoperative cervical radiograph.

Flexion radiograph of the fusion construct at the 3-month follow-up appointment.

Fig. 9. Postoperative cervical radiograph.

Extension radiograph of the fusion construct at the 3-month follow-up appointment.

Fig. 10. Postoperative cervical radiograph.

Lateral radiograph of the fusion construct at the 6-month follow-up appointment.

Fig. 11. Postoperative cervical radiograph.

Extension radiograph of the fusion construct at the 6-month follow-up appointment.

Fig. 12. Postoperative cervical radiograph.

Flexion radiograph of the fusion construct at the 6-month follow-up appointment.

Discussion

Historically, surgical approaches to AAI included the Gallie fusion [23], Brooks fusion [21], interlaminar clamping, and multiple modifications of these procedures [25–28]. More recently, transarticular screw fixation and C1 screw-and-rod constructs utilizing either C2 pars or C2 pedicle screws have become the new standard of care for C1–2 fusion in the setting of AAI [24, 27, 30, 40–44]. In a recent systematic review comparing these two constructs, both systems were associated with favorable, equivalent fusion rates [30]. In this case report, our patient presented with AAI and a flexion–extension MRI demonstrating posterior cord compression by the posterior ring of C1. Following C1–2 arthrodesis with C1 lateral mass screws and C2 pars screws, postoperative flexion–extension radiographs demonstrated reduction of the atlantoaxial subluxation and no instability at the C1–2 junction.

The surgical treatment of subaxial myelopathy involves utilization of decompressive procedures such as laminoplasty [31, 32, 35–37] or multilevel laminectomy and fusion [29, 33, 34]. Cervical laminoplasty has the distinct advantage of preserving motion through the subaxial cervical spine and is commonly utilized in patients with minimal neck pain and adamant interest in preserving motion. For this reason, cervical laminoplasty has been a commonly used procedure for compressive spondylotic myelopathy and has demonstrated satisfactory long-term results in this setting [32, 35, 45]. However, conventional C3 laminoplasty involved transiently detaching the SSC insertion from the C2 spinous process in order to access C3 for laminoplasty and then repairing the C2 insertion at the time of wound closure [31]. This technique fell out of favor due to poor patient reported outcomes thought to be related to high failure rates of the SSC insertion repair [31], resulting in cervical malalignment and the development of persistent axial symptoms [46–48]. To avoid complications associated with failed repair of the SSC insertion, Takeuchi et al. devised a new protocol for subaxial decompression that involved performing a C3 laminectomy with C4–7 laminoplasties [37], thus permitting decompression of the C2–3 segment without violation of the SSC insertion. Results of this new protocol demonstrated an increase in the percentage of patients without postoperative axial symptoms from 19 to 52.5% (p = 0.035) and a decrease in the percentage of patients with relative worsening symptoms postoperatively from 50 to 17.5% (p = 0.020). Since its publication, this new laminoplasty technique has gained popularity due to the relative ease of the C3 laminectomy compared to C3 laminoplasty, the preservation of the SSC insertion on C2, and its utility in the management of compressive spondylotic cervical myelopathy. In our case report, the patient’s MRI demonstrated subaxial spondylotic stenosis from C3–7 with cord compression and associated T2 signal change at C5–6. A C3 laminectomy was performed, thereby preserving the insertion of the SSC on the spinous process of C2, followed by C4–6 laminoplasties and, as a slight variation of the protocol, a C7 dome laminectomy. When seen at postoperative follow-up his gait instability and weakness were markedly improved, and flexion–extension radiographs demonstrated normal motion through his subaxial cervical spine.

Though the literature pertaining to the treatment of AAI and subaxial spondylotic stensosis as individual entities is vast, there is no study available in the literature that discusses the treatment of these pathologies when they present concomitantly in RA. In our patient with AAI, C1–2 arthrodesis was indicated to relieve the deforming cord compression by the posterior arch of C1 as demonstrated on flexion MRI. However, our patient also presented with concomitant findings of subaxial spondylotic stenosis and cord compression with T2 signal change at C5–6 and physical examination findings consistent with myelopathy, necessitating a subaxial cervical decompression. In order to preserve motion through the subaxial cervical spine, our patient underwent a C3 laminectomy and C4–7 laminoplasty. Unlike conventional C3–7 laminoplasty techniques, our approach preserved both cervical motion and the insertion of the SSC on the C2 spinous process, which has been associated with a reduced rate of postoperative axial symptoms [37].

Patients with RA who present with concomitant AAI and subaxial spondylotic stenosis represent a treatment challenge. Though these patients clearly require a C1–2 arthrodesis, appropriate treatment of the subaxial stenosis is less clear. There are no studies in the literature investigating surgical treatment of these pathologies when they occur together. In this case report, we describe the treatment of concomitant AAS and subaxial spondylotic stenosis in an RA patient via a C1–2 arthrodesis utilizing C1 lateral mass screws and C2 pars screws, C3 laminectomy, and C4–7 laminoplasties. Utilizing this approach, we were able to stabilize the patient’s atlantoaxial junction, decompress the subaxial spinal cord, preserve the SSC, and preserve motion in the subaxial cervical spine. This is the first study to describe the surgical management of an RA patient with concomitant AAS and subaxial spondylotic stenosis. Patients with these concomitant pathologies who deny significant neck pain, lack imaging findings consistent with SAS, and adamantly desire to pursue motion-sparing procedures can be considered for decompression caudal to the C1–2 arthrodesis, though they should be adequately counseled regarding the risk of developing SAS requiring subsequent fusion.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Linos A, Worthington JW, O’Fallon M, Kurland LT. The epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis in Rochester Minnesota: a study of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 1980;111:87–98. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halla JT, Hardin JG, Vitek J, Alarcón GS. Involvement of the cervical spine in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:652–9. doi: 10.1002/anr.1780320522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heywood A, Learmonth I, Thomas M. Cervical spine instability in rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 1988;70:702–7. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.70B5.3192564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moncur C, Williams HJ. Cervical spine management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: review of the literature. Phys Ther. 1988;68:509–15.. doi: 10.1093/ptj/68.4.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujiwara K, Owaki H, Fujimoto M, Yonenobu K, Ochi T. A long-term follow-up study of cervical lesions in rheumatoid arthritis. J Spinal Disord. 2000;13:519–26.. doi: 10.1097/00002517-200012000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pellicci PM, Ranawat CS, Tsairis P, Bryan WJ. A prospective study of the progression of rheumatoid arthritis of the cervical spine. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1981;63:342–50.. doi: 10.2106/00004623-198163030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wasserman BR, Moskovich R, Razi AE. Rheumatoid arthritis of the cervical spine-clinical considerations. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2011;69:136–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yurube T, Sumi M, Nishida K, Miyamoto H, Kohyama K, Matsubara T, et al. Incidence and aggravation of cervical spine instabilities in rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective minimum 5-year follow-up study of patients initially without cervical involvement. Spine. 2012;37:2136–44.. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31826def1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isdale IC, Conlon PW. Atlanto-axial subluxation. A 6-year follow-up report. Ann Rheum Dis. 1971;30:387–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.30.4.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martel W. The occipito-atlanto-axial joints in rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1961;86:223–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathews JA. Atlanto-axial subluxation in rheumatoid arthritis. A 5-year follow-up study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1974;33:526–31.. doi: 10.1136/ard.33.6.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rana NA. Natural history of atlanto-axial subluxation in rheumatoid arthritis. Spine. 1989;14:1054–6. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198910000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharp J, Purser DW. Spontaneous atlanto-axial dislocation in ankylosing spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1961;20:47–77. doi: 10.1136/ard.20.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ranawat CS, O’Leary P, Pellicci P, Tsairis P, Marchisello P, Dorr L. Cervical spine fusion in rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1979;61:1003–10.. doi: 10.2106/00004623-197961070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Redlund-Johnell I, Pettersson H. Radiographic measurements of the cranio-vertebral region. Designed for evaluation of abnormalities in rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Radiol Diagn. 1984;25:23–8. doi: 10.1177/028418518402500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yonezawa T, Tsuji H, Matsui H, Hirano N. Subaxial lesions in rheumatoid arthritis. Radiographic factors suggestive of lower cervical myelopathy. Spine. 1995;20:208–15. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199501150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsunaga S, Sakou T, Onishi T, Hayashi K, Taketomi E, Sunahara N, et al. Prognosis of patients with upper cervical lesions caused by rheumatoid arthritis: comparison of occipitocervical fusion between c1 laminectomy and nonsurgical management. Spine. 2003;28:1581–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paus AC, Steen H, Røislien J, Mowinckel P, Teigland J. High mortality rate in rheumatoid arthritis with subluxation of the cervical spine: a cohort study of operated and nonoperated patients. Spine. 2008;33:2278–83.. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817f1a17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grob D. Atlantoaxial immobilization in rheumatoid arthritis: a prophylactic procedure? Eur Spine J. 2000;9:404–9. doi: 10.1007/s005860000174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sunahara N, Matsunaga S, Mori T, Ijiri K, Sakou T. Clinical course of conservatively managed rheumatoid arthritis patients with myelopathy. Spine. 1997;22:2603–7. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199711150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brooks AL, Jenkins EB. Atlanto-axial arthrodesis by the wedge compression method. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1978;60:279–84.. doi: 10.2106/00004623-197860030-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clark CR, Goetz D, Menezes A. Arthrodesis of the cervical spine in rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1989;71:381–92.. doi: 10.2106/00004623-198971030-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gallie W. Fractures and dislocations of the cervical spine. Am J Surg. 1939;46:495–9. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(39)90309-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goel A, Laheri V. Plate and screw fixation for atlanto-axial subluxation. Acta Neurochir. 1994;129:47–53. doi: 10.1007/BF01400872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grob D, Dvorak J, Panjabi M, Froehlich M, Hayek J. Posterior occipitocervical fusion. A preliminary report of a new technique. Spine. 1991;16:S17–24. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199103001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grob D, Magerl F. Surgical stabilization of C1 and C2 fractures. Orthopade. 1987;16:46–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harms J, Melcher RP. Posterior C1–C2 fusion with polyaxial screw and rod fixation. Spine. 2001;26:2467–71.. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200111150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wertheim SB, Bohlman H. Occipitocervical fusion. Indications, technique, and long-term results in thirteen patients. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1987;69:833–6. doi: 10.2106/00004623-198769060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.An HS, Gordin R, Renner K. Anatomic considerations for plate-screw fixation of the cervical spine. Spine. 1991;16:S548–51. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199110001-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elliott RE, Tanweer O, Boah A, Morsi A, Ma T, Frempong-Boadu A, et al. Outcome comparison of atlantoaxial fusion with transarticular screws and screw-rod constructs: meta-analysis and review of literature. Clin Spine Surg. 2014;27:11–28. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e318277da19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iizuka H, Shimizu T, Tateno K, Toda N, Edakuni H, Shimada H, et al. Extensor musculature of the cervical spine after laminoplasty: morphologic evaluation by coronal view of the magnetic resonance image. Spine. 2001;26:2220–6. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200110150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawaguchi Y, Kanamori M, Ishihara H, Ohmori K, Nakamura H, Kimura T. Minimum 10-year followup after en bloc cervical laminoplasty. CORR. 2003;411:129–39. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000069889.31220.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Magerl F, Seemann P-S (1987) Stable posterior fusion of the atlas and axis by transarticular scree fixation. In: Kehr P, Weildner A (eds) Cervical spine 1, Strasbourg 1985, Springer, Vienna, 1987, pp 322–7.

- 34.Roy-Camille R, Mazel C, Saillant G, et al. Rationale and techniques of internal fixation in trauma of the cervical spine, in Errico TJ, Bauer RD, Waugh T (eds) Spinal Trauma. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1991, Vol 1, pp 163–9.

- 35.Seichi A, Takeshita K, Ohishi I, Kawaguchi H, Akune T, Anamizu Y, et al. Long-term results of double-door laminoplasty for cervical stenotic myelopathy. Spine. 2001;26:479–87.. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200103010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shiraishi T, Fukuda K, Yato Y, Nakamura M, Ikegami T. Results of skip laminectomy-minimum 2-year follow-up study compared with open-door laminoplasty. Spine. 2003;28:2667–72.. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000103340.78418.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takeuchi K, Yokoyama T, Aburakawa S, Saito A, Numasawa T, Iwasaki T, et al. Axial symptoms after cervical laminoplasty with C3 laminectomy compared with conventional C3-C7 laminoplasty: a modified laminoplasty preserving the semispinalis cervicis inserted into axis. Spine. 2005;30:2544–9. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000186332.66490.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clarke MJ, Cohen-Gadol AA, Ebersold MJ, Cabanela ME. Long-term incidence of subaxial cervical spine instability following cervical arthrodesis surgery in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Surg Neurol. 2006;66:136–40. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2005.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ito H, Neo M, Sakamoto T, Fujibayashi S, Yoshitomi H, Nakamura T. Subaxial subluxation after atlantoaxial transarticular screw fixation in rheumatoid patients. Eur Spine J. 2009;18:869–76.. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-0945-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goel A, Dange N. Immediate postoperative regression of retroodontoid pannus after lateral mass reconstruction in a patient with rheumatoid disease of the craniovertebral junction: case report. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;9:273–6. doi: 10.3171/SPI/2008/9/9/273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goel A, Pareikh S, Sharma P. Atlantoaxial joint distraction for treatment of basilar invagination secondary to rheumatoid arthritis. Neurol India. 2005;53:238. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.16424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goel A, Sharma P. Craniovertebral realignment for basilar invagination and atlantoaxial dislocation secondary to rheumatoid arthritis. Neurol India. 2004;52:338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Härtl R, Chamberlain RH, Fifield MS, Chou D, Sonntag VK, Crawford NR. Biomechanical comparison of two new atlantoaxial fixation techniques with C1-2 transarticular screw-graft fixation. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;5:336–42. 10.3171/spi.2006.5.4.336. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Sim HB, Lee JW, Park JT, Mindea SA, Lim J, Park J. Biomechanical evaluations of various c1-c2 posterior fixation techniques. Spine. 2011;36:E401–7.. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31820611ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wada E, Suzuki S, Kanazawa A, Matsuoka T, Miyamoto S, Yonenobu K. Subtotal corpectomy versus laminoplasty for multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a long-term follow-up study over 10 years. Spine. 2001;26:1443–7. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200107010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hosono N, Yonenobu K, Ono K. Neck and shoulder pain after laminoplasty. A noticeable complication. Spine. 1996;21:1969–73. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199609010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kawaguchi Y, Matsui H, Ishihara H, Gejo R, Yoshino O. Axial symptoms after en bloc cervical laminoplasty. J Spinal Disord. 1999;12:392–5. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199912050-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshida M, Tamaki T, Kawakami M, Nakatani N, Ando M, Yamada H, et al. Does reconstruction of posterior ligamentous complex with extensor musculature decrease axial symptoms after cervical laminoplasty? Spine. 2002;27:1414–8. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200207010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]