Abstract

Introduction

The treatment of intestinal perforation caused by the SBC enters the small intestine in elderly patients is a challenge for urologists. The report is to share our experience of conservative treatment after a 90-year-old male with the suprapubic bladder catheter enters the small intestine.

Presentation of case

Because of the device was obstructed, a 90-year-old male went to our hospital with his family and requested to replace the SBC. When the fistula tube was replaced, it entered the intestine through the intestinal injury site instead of entering the bladder. During the hospitalization, the patient was given supportive treatments and the SBC was dynamically monitored daily and it was intermittently withdrawn out during this period. After the drainage volume was less than 10 mL for three consecutive days and the intestinal fistula was healing gradually, the catheter was taken out.

Discussion

According to our experience, the common complications in the process include failure to pull out the SBC, abnormal position of the SBC, and poor drainage of the SBC. However, the drainage tube placing into the small intestine through the original hole of the suprapubic bladder fistula during the replacement process is quite rare. When elderly patients have traumatic small bowel perforation, the diagnosis and treatment of intestinal perforation in elderly patients was particularly important.

Conclusion

The conservative treatment of intestinal perforation is suitable for elderly patients who are unsuitable or unwilling to undergo a surgical operation. Of course, it should be in accordance with the patient's condition to make the right choice of treatment.

Abbreviations: SBC, suprapubic bladder catheter; SBCI, suprapubic bladder catheter insertion

Keywords: Suprapubic bladder catheter insertion, Intestinal perforation, Conservative treatment

1. Introduction

Suprapubic bladder catheter insertion (SBCI) is suitable for bladder obstruction due to benign prostatic hyperplasia, urethral stricture or phimosis. In addition, SBCI can also be used as a simple solution for indwelling catheterization in patients with severe urinary incontinence or neurogenic bladder outlet dysfunction [[1], [2], [3]]. For patients who retained the SBC for a long time, replacing the SBC is a basic operation in the clinical work of urologists. However, it is very rare for that the SBC enters the small intestine during the replacement process. The treatment of intestinal perforation caused by the SBC enters small intestine in elderly patients is also a challenge for urologists. To date, there is a lack of relevant research reports and case sharing.

In this study, we reported a rare case to share our experience of conservative treatment after a 90-year-old male with the suprapubic bladder catheter enters the small intestine. This study is reported in line with the SCARE checklist [4].

2. Presentation of case

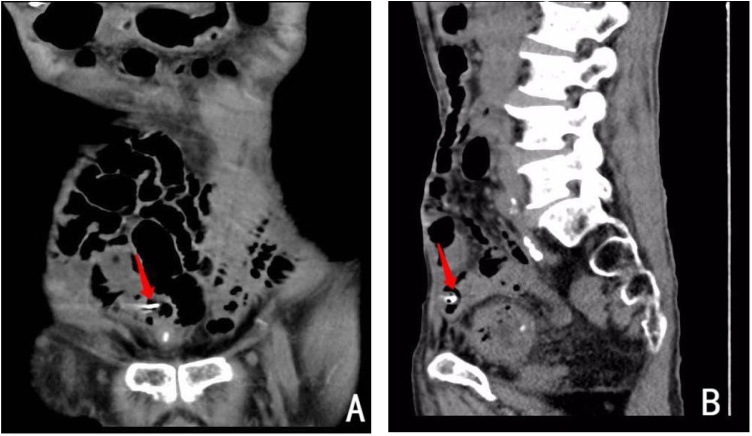

A 90-year-old male underwent a suprapubic cystostomy in our hospital on January 22, 2019, due to acute urinary retention caused by neurogenic bladder. The SBC was in him for a long time after the operation, even though it was recommended to replace the device every month. On September 22, 2019, the patient felt that the SBC was obstructed, and the patient's family repeatedly used an iron wire (approximately 4 mm in diameter) to unblock it. However, the drainage tube was still clogged. Therefore, he went to our hospital with his family and requested to replace the SBC. When we took out the original bladder catheter, a little dark green liquid could be seen at the tip. After we replaced it, the liquid, which was suspected of intestinal juice, was spotted to draw out. Therefore, we immediately performed CT examination of the patient's lower abdomen. Results showed a significant dilation of the intestine, and the replacement device was suspected to be placed in the small intestine (Fig. 1: A, B). We performed a urinary catheterization and indwelled the urinary catheter for the patient at the bedside. Then the yellow urine was leading out, which was significantly different in color from the SBC (Fig. 2). Therefore, it is confirmed that the SBC did not enter the bladder but entered the small intestine.

Fig. 1.

CT of the lower abdomen. The tip of the suprapubic bladder catheter was located in the small intestine.

Fig. 2.

The dark green drainage fluid on the left is suspected of intestinal fluid.

His surgical history was significant with two laparotomies: 1. Thirty years ago, the intestinal repair was performed at the local hospital due to traumatic intestinal rupture. 2. On November 15, 2018, he went through the right ureteral bladder replantation and double J tube drainage in our hospital.

In the first two weeks after hospitalization, the patient received supportive treatments such as diet prohibition, anti-infection, acid suppression, parenteral nutrition support, and maintenance of electrolyte balance in the body. During this period, the amount of intestinal juice through the SBC was dynamically monitored daily. After two weeks, the patient was allowed on a fluid diet, and the drainage of the SBC was monitored daily. In addition, the device was withdrawn out intermittently during the period. After the drainage volume was less than 10 mL for three consecutive days (Fig. 3), and the intestinal fistula healed gradually, the catheter was pulled out. The patient continued to stay in the hospital for the abdominal observation. After 3 days, the whole abdominal CT examination confirmed that there was no intestinal fistula, the patient was allowed to be discharged.

Fig. 3.

Daily drainage volume of the suprapubic bladder catheter.

3. Discussion

SBCI is a common operation for patients with acute urinary retention who have failed transurethral catheterization in clinical work. There are few reports concerning the safety of this procedure, but it is considered to be safe and simple. Although it is highly recognized in clinical work, this procedure has certain shortcomings, especially the various complications of the placement process such as hematuria or catheter displacement, in which severe complications can lead to intestinal perforation and even death [5,6]. Hall et al. [7] analyzed that among 11,473 patients who underwent suprapubic catheter insertion, only one case was identified with bowel injury. Therefore, bowel injury caused by the SBCI is very rare in practical clinical work.

Since replacing the SBC is a simple operation, there are not much efforts and attention on it from clinicians. According to our experience, the common complications in the process include failure to pull out the SBC, abnormal position of the SBC, and poor drainage of the SBC. However, the drainage tube placing into the small intestine through the original hole of the suprapubic bladder fistula during the replacement process is quite rare. This case is about a 90-year-old patient with poor nutrition, thin abdominal wall, decreased bowel excretion function, and obvious bowel dilation. In addition, the patient has experienced bowel surgery and lower abdomen surgery before. Local tissues are prone to form adhesions with the small intestine. The process of dredging the pipes with sharp instruments by family members can easily damage the small intestine. When the suprapubic bladder fistula was changed on admission, the bladder collapsed, causing the disappearance of the original hole. When the fistula tube was replaced through the original hole of the suprapubic bladder fistula, the fistula tube entered the intestine through the intestinal injury site but not the bladder.

When elderly patients have traumatic small bowel perforation, they are easy to be misdiagnosed by missing the unclear expression and unobvious abdominal signs. Therefore, the diagnosis of intestinal perforation in elderly patients is particularly important. In addition, for older patients with poor general conditions, the choice of treatment for gastrointestinal perforation should be more careful. For the treatment of gastrointestinal perforation, The preferred intervention is the emergent surgical repair [8,9]. While, for these patients unsuitable or unwilling to undergo operation, nonsurgical treatment is preserved [10].

In our experience, the keys to the success of conservative treatment lies in: 1. Early and timely diagnosis; in this case, the color of the drainage fluid was suspected to be intestinal fluid which was spotted after replacing the SBC, and the diagnosis was quickly confirmed by CT of the lower abdomen. 2. Strictly master the indications; the patient is a 90-year-old with poor nutrition, who also has high surgical risks. Therefore, an emergency surgery is not considered before obvious signs of acute peritonitis appear, and conservative treatment is recommended. 3. Unobstructed, effective, and sufficient time for gastrointestinal decompression; in this case, the SBC reinserted in this patient entered into the intestine through the small intestinal perforation, forming a drainage tube that was connected to the outside world, which largely ensured that intestinal fluid did not enter the abdominal cavity and cause the symptoms of peritoneal irritation. Therefore, the patient had no obvious signs of acute peritonitis after the onset of the disease, which also provided a guarantee for the conservative treatment of the patient. During this period, the amount of intestinal juice through the SBC was dynamically monitored daily. After the drainage volume was less than 10 mL for three consecutive days, and the intestinal fistula healed gradually, the catheter was taken out. 4. Effective supportive treatment; the patients were given supportive treatments such as diet prohibition, anti-infection, acid suppression, parenteral nutrition support, and maintenance of electrolyte balance in the body. 5. Observation of abdominal signs; after the conservative treatment, the symptoms tend to stabilize. In addition, whether the abdominal distension is aggravated is particularly important in the process of disease assessment. For those with mild abdominal distension or not worsened after treatment, most conservative treatments can be successful. In this case, the patient's abdominal signs were stable during the treatment period, especially after eating and removing the drainage tube. Since no abdominal signs were aggravated, it is suggested that the conservative treatment was effective.

4. Conclusion

The conservative treatment of intestinal perforation is suitable for elderly patients who are unsuitable or unwilling to undergo a surgical operation. Of course, it should be in accordance with the patient's condition to make the right choice of treatment.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Funding

This study was funded by grants from the National Natural Science Cultivate Foundation of Guizhou Provincial People’s Hospital ([2018]5764-0). The main function of the funding in this study was to support the study design and writing of the report.

Ethical approval

This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Guizhou Provincial People's Hospital. The committee approved the requirement for verbal informed consent to be obtained from participants.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Author contribution

BW contributed to the study design, data collection, interpretation and manuscript writing. DP contributed to data collection and interpretation. GHL and ZLS contributed to data analysis and manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Registration of research studies

Not Applicable.

Guarantor

Bo Wang.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Contributor Information

Bo Wang, Email: 761446379@qq.com.

Di Pan, Email: 383590624@qq.com.

Guangheng Luo, Email: luoguangheng1975@163.com.

Zhaolin Sun, Email: szl5926186@163.com.

References

- 1.Harrison Simon C.W., Lawrence W.T., Morley R. British Association of Urological Surgeons’ suprapubic catheter practice guidelines. BJU Int. 2011;107:77–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geng V., Cobussen-Boekhorst H., Farrell J. Evidence-based Guidelines for Best Practice in Urological Health Care. European Association of Urology Nurses (EAUN); Arnhem (The Netherlands): 2012. Catheterisation indwelling catheters in adults. Urethral and suprapubic. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feifer A., Corcos J. Contemporary role of suprapubic cystostomy in treatment of neuropathic bladder dysfunction in spinal cord injured patients. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2008;27:475–479. doi: 10.1002/nau.20569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrabi C., Mathew G.G., for the SCARE Group The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;84 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahluwalia R.S., Johal N., Kouriefs C. The surgical risk of suprapubic catheter insertion and long-term sequelae. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2006;88:210–213. doi: 10.1308/003588406X95101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheriff M.K., Foley S., McFarlane J. Long-term suprapubic catheterisation: clinical outcome and satisfaction survey. Spinal Cord. 1998;36:171–176. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall S., Ahmed S., Reid S. A national UK audit of suprapubic catheter insertion practice and rate of bowel injury with comparison to a systematic review and meta-analysis of available research. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2019;38:2194–2199. doi: 10.1002/nau.24114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Behrman S.W. Management of complicated peptic ulcer disease. Arch. Surg. 2005;140:201–208. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lohsiriwat V., Prapasrivorakul S., Lohsiriwat D. Perforated peptic ulcer: clinical presentation, surgical outcomes, and the accuracy of the Boey scoring system in predicting postoperative morbidity and mortality. World J. Surg. 2009;33:80–85. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9796-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bertleff Mariëtta J.O.E., Lange J.F. Perforated peptic ulcer disease: a review of history and treatment. Dig. Surg. 2010;27:161–169. doi: 10.1159/000264653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]