Key Points

Question

In patients with acute large vessel occlusion stroke, is mechanical thrombectomy alone noninferior to combined intravenous thrombolysis using 0.6-mg/kg alteplase plus mechanical thrombectomy regarding functional outcomes?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 204 patients, a favorable functional outcome occurred in 59.4% of those randomized to mechanical thrombectomy alone and in 57.3% of those randomized to combined intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy (odds ratio, 1.09 [95% confidence limit below the noninferiority margin of 0.74]).

Meaning

The findings failed to demonstrate noninferiority of mechanical thrombectomy alone, compared with combined intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy, for favorable functional outcome following acute large vessel occlusive ischemic stroke, although the wide confidence intervals around the effect estimate also did not allow a conclusion of inferiority.

Abstract

Importance

Whether intravenous thrombolysis is needed in combination with mechanical thrombectomy in patients with acute large vessel occlusion stroke is unclear.

Objective

To examine whether mechanical thrombectomy alone is noninferior to combined intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy for favorable poststroke outcome.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Investigator-initiated, multicenter, randomized, open-label, noninferiority clinical trial in 204 patients with acute ischemic stroke due to large vessel occlusion enrolled at 23 hospital networks in Japan from January 1, 2017, to July 31, 2019, with final follow-up on October 31, 2019.

Interventions

Patients were randomly assigned to mechanical thrombectomy alone (n = 101) or combined intravenous thrombolysis (alteplase at a 0.6-mg/kg dose) plus mechanical thrombectomy (n = 103).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary efficacy end point was a favorable outcome defined as a modified Rankin Scale score (range, 0 [no symptoms] to 6 [death]) of 0 to 2 at 90 days, with a noninferiority margin odds ratio of 0.74, assessed using a 1-sided significance threshold of .025 (97.5% CI). There were 7 prespecified secondary efficacy end points, including mortality by day 90. There were 4 prespecified safety end points, including any intracerebral hemorrhage and symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage within 36 hours.

Results

Among 204 patients (median age, 74 years; 62.7% men; median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score, 18), all patients completed the trial. Favorable outcome occurred in 60 patients (59.4%) in the mechanical thrombectomy alone group and 59 patients (57.3%) in the combined intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy group, with no significant between-group difference (difference, 2.1% [1-sided 97.5% CI, −11.4% to ∞]; odds ratio, 1.09 [1-sided 97.5% CI, 0.63 to ∞]; P = .18 for noninferiority). Among the 7 secondary efficacy end points and 4 safety end points, 10 were not significantly different, including mortality at 90 days (8 [7.9%] vs 9 [8.7%]; difference, –0.8% [95% CI, –9.5% to 7.8%]; odds ratio, 0.90 [95% CI, 0.33 to 2.43]; P > .99). Any intracerebral hemorrhage was observed less frequently in the mechanical thrombectomy alone group than in the combined group (34 [33.7%] vs 52 [50.5%]; difference, –16.8% [95% CI, –32.1% to –1.6%]; odds ratio, 0.50 [95% CI, 0.28 to 0.88]; P = .02). Symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage was not significantly different between groups (6 [5.9%] vs 8 [7.7%]; difference, –1.8% [95% CI, –9.7% to 6.1%]; odds ratio, 0.75 [95% CI, 0.25 to 2.24]; P = .78).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients with acute large vessel occlusion stroke, mechanical thrombectomy alone, compared with combined intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy, failed to demonstrate noninferiority regarding favorable functional outcome. However, the wide confidence intervals around the effect estimate also did not allow a conclusion of inferiority.

Trial Registration

umin.ac.jp/ctr Identifier: UMIN000021488

This noninferiority trial compares the effects of mechanical thrombectomy with vs without intravenous thrombolysis (0.6-mg/kg alteplase) on 90-day disability among patients with acute large vessel occlusive ischemic stroke.

Introduction

Randomized trials have consistently shown that mechanical thrombectomy with or without intravenous thrombolysis using recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) can improve the outcome in patients with acute stroke due to large vessel occlusion.1,2,3,4,5,6,7 Intravenous thrombolysis (with dosage of 0.9-mg/kg alteplase) prior to mechanical thrombectomy is recommended by national guidelines for patients with large vessel occlusion, within 4.5 hours of symptom onset.8,9,10

A meta-analysis of 5 randomized clinical trials reported that outcomes following mechanical thrombectomy did not differ significantly between patients receiving and not receiving intravenous thrombolysis.11 However, this concerned an observational comparison because intravenous thrombolysis was withheld only in the presence of contraindications for rt-PA. A retrospective study also showed that the outcomes between mechanical thrombectomy alone and combined intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy were not significantly different.12 However, a meta-analysis showed the combined intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy was associated with favorable outcome compared with mechanical thrombectomy alone.13

Intravenous thrombolysis performed in addition to mechanical thrombectomy in patients with large vessel occlusion has some potential benefits, such as earlier therapy initiation and increased chance of reperfusion. However, intravenous thrombolysis in addition to mechanical thrombectomy may increase the risk of intracerebral hemorrhage and other bleeding complications.14 Noninferiority of mechanical thrombectomy alone, compared with combined therapy, would have potential clinical consequences because the extra cost and stroke team labor associated with intravenous thrombolysis could be avoided if outcomes of mechanical thrombectomy alone were not worse than outcomes of combined therapy.

The Direct Mechanical Thrombectomy in Acute LVO Stroke (SKIP) study was designed to evaluate whether the outcomes with mechanical thrombectomy alone were noninferior than the outcomes with combined thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy.

Methods

Trial Design and Oversight

This trial was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of each hospital. Enrolled patients or their relatives provided written informed consent. This trial was an investigator-initiated, multicenter, randomized, open-label, noninferiority clinical trial. Detailed aspects of the study design are provided in the final trial protocol with summary of all changes (Supplement 1), the final statistical analysis plan with summary of all changes (Supplement 2), and a prior trial design publication.15 The study was to test whether mechanical thrombectomy alone was noninferior to combined intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy with regard to functional outcome in intravenous thrombolysis–eligible patients. All patients were required to have large vessel occlusion without large ischemic core lesions.

Patients and Participating Centers

This study was performed at 23 stroke centers capable of endovascular therapy in Japan. Patients were allowed to be evaluated in another hospital and transferred to one of the study centers. Eligible patients were 18 to 85 years old, had acute stroke with internal carotid artery (ICA) or M1 occlusion evaluated by magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) or computed tomographic angiography (CTA), had a baseline Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECTS) (range, 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating fewer early ischemic changes) of 6 to 10 or Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI)–ASPECTS (range, 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating fewer early ischemic changes) of 5 to 10, initial National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score (range, 0 [no symptoms] to 42 [most severe neurologic deficits]) equal to 6 or greater, were functionally independent prior to stroke, with modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score (range, 0 [no symptoms] to 6 [death]) of 0 to 2 , and met the criteria of the Japanese guidelines for treatment with the lower dose of 0.6 mg/kg of alteplase as intravenous thrombolysis within 4.5 hours from onset.16 The NIHSS score was assessed at baseline. The mRS score was assessed at 90 days after onset. For detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria, see eBox 1 in Supplement 3.

Randomization and Interventions

Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to 1 of 2 treatment groups using a web-based data management system: the mechanical thrombectomy alone group or the combined group. Using a stratified permuted block method (a block size of 4), we balanced the number of patients into the 2 treatment groups of each hospital. Alteplase was used at the only dosage (0.6 mg/kg) approved by the Japanese government. Mechanical thrombectomy was performed with any device approved by the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan. Balloon guide catheter was selected as the guiding catheter on mechanical thrombectomy. Concomitant stenting and angioplasty of cervical and intracranial ICA occlusive lesions were permitted without device restrictions. All stroke centers were required to start mechanical thrombectomy within 30 minutes from randomization. rt-PA infusion was continued during mechanical thrombectomy for those in the combined intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy group.

Radiologic Assessment

At admission, the baseline clinical characteristics were assessed by research physicians at each hospital, including the NIHSS score, occluded artery site17 at admission and start of mechanical thrombectomy, ASPECTS on MRI or CT, and expanded Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction (eTICI) scale score (range, 0-3, higher scores indicate better reperfusion) on digital subtraction angiography. After enrolling all patients, a core imaging assessment committee (2 expert neurologists, S.F. and T. Hirano), who were blinded to the intervention, independently reassessed the occlusion site, ASPECTS, and presence of intracerebral hemorrhage as prespecified adverse events. Clot migration was defined as change of occlusion site on findings between initial MRA/CTA and initial digital subtraction angiography.

Outcome Measures

The mRS score was assessed by physical examination or telephone interview at 90 days after onset by site personnel who were blinded to treatment group assignment. The primary outcome measure was favorable outcome defined as an mRS score of 0 to 2 at 90 days. In a sensitivity analysis, primary outcome results were analyzed using per-protocol analysis.

The prespecified secondary outcome measures were shift analysis of disability levels on the mRS; mRS score of 5 to 6; mRS score of 0 to 1; mRS score of 0 to 3; mortality at 90 days; successful reperfusion defined as an eTICI scale18 score of 2b to 3 on end-of-procedure catheter angiography; recanalization, defined as modified Mori scale19 score of 2 to 3 (scale ranges from 0 [no recanalization] to 3 [nearly complete recanalization]) on 48-hour CTA/MRA.

The prespecified adverse events were any intracerebral hemorrhage at 36 hours from onset; symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage defined by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) criteria20; symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage defined by Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke–Monitoring Study (SITS-MOST) criteria21; and other major bleeding events (eBox 2 in Supplement 3).

In the initial protocol, the investigators requested that the IRB allow use of mRS scores of 0 to 2 for noninferiority in the primary analysis. However, the IRB suggested to the investigators to change from an mRS score of 0 to 2 for noninferiority to an mRS score of 5 to 6 for superiority in the primary analysis prior to study start because there were no confirmed data to support the mRS score of 0 to 2 approach compared with the mRS score of 5 to 6 approach. After 103 patients had been enrolled in this trial, Weber et al22 reported an observational study that provided more data regarding the end point of an mRS score of 0 to 2. Consequently, the IRB accepted the use of an mRS score of 0 to 2 for noninferiority in the primary analysis. Therefore, on August 1, 2018, the primary outcome was changed from superiority for poor outcome to noninferiority for favorable outcome. Study investigators had not reviewed any patient data before the primary outcome change. The study investigators included stroke neurologists, neurosurgeons, and statisticians. This trial was monitored by an independent data monitoring committee and event evaluation committee.

Noninferiority Margin and Sample Size Calculations

In a retrospective analysis of patients eligible for intravenous thrombolysis, Weber et al22 reported favorable functional outcome (mRS score 0-2) in 48.6% of patients (n = 70) who had received mechanical thrombectomy alone and 35.2% of those (n = 105) who received intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy. As described in detail in the published study protocol for this study,15 the noninferiority margin was set as the odds ratio of 0.74 using the fixed-margin approach, which was derived from a previous meta-analysis of combined intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy compared with the best medical treatment.11 Based on those results, it was estimated that 178 patients (89 patients in each group) were needed to statistically show the noninferiority of the odds ratio for the primary outcome in the mechanical thrombectomy alone group compared with the intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy group, based on comparison of the 2 proportions with a 1-sided α level of .025 and a power of 0.80. Therefore, the target enrollment was set at 200 patients because of considering possible treatment failures, protocol violations, and dropouts. Detailed information on the calculation of sample size is described in the statistical analysis plan in Supplement 2.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using the primary analysis set, which was defined as all patients enrolled to the trial.

In the primary analysis, patients were analyzed according to the group to which they were randomized. The primary analysis involved testing for noninferiority of the rate of a favorable outcome at 90 days of mechanical thrombectomy alone compared with combined intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy. Unadjusted logistic regression analysis was used to test noninferiority. As described in detail in the protocol,15 we set an odds ratio of 0.74 as the noninferiority margin, using the fixed-margin approach, which was derived from a previous meta-analysis of combined intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy compared with the best medical treatment.11 As sensitivity analysis of the primary outcome, noninferiority analyses of a favorable outcome was also performed using the per-protocol analysis set, which excluded patients with mRS scores prior to stroke higher than 2 and a large volume infarct (ASPECTS of 0-5 or DWI-ASPECTS of 0-4) from the primary analysis set.

In the prespecified secondary efficacy analysis, the mRS scores were compared between groups to test for the noninferiority of mechanical thrombectomy compared with combined intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy, using ordinal logistic regression (shift analysis). The proportional odds assumption of the shift analysis was validated by a Brant test. Furthermore, mortality at 90 days; reperfusion rate of the occluded arteries; mRS score of 5 to 6, 0 to 1, or 0 to 3 at 90 days; and recanalization of modified Mori grade of 2 or 3 at 72 hours after stroke onset were compared between the 2 groups using unadjusted logistic regression analysis.

As prespecified adverse events, any and symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage and other bleeding events were assessed for superiority of mechanical thrombectomy alone compared with combined therapy. In the post hoc analysis, mixed-effect logistic regression analysis of the primary outcome was performed with study site as a random effect. In addition, association between any intracerebral hemorrhage and clinical outcome at 90 days, and subgroup plot–adjusted treatment effect for favorable outcome were assessed.

The primary noninferiority analysis used a 1-sided significance threshold of .025, as did all other noninferiority analyses. Superiority analyses used a 2-sided significance threshold of .05. The heterogeneity of treatment effects on the primary outcome across subgroups was examined using an interaction test for the treatment × subgroup interaction. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, findings for analyses of secondary end points and subgroup analyses should be interpreted as exploratory.

All data analyses were performed with JMP version 11 software (SAS Institute) and Stata version 14 software (StataCorp).

Results

Characteristics of the Patients

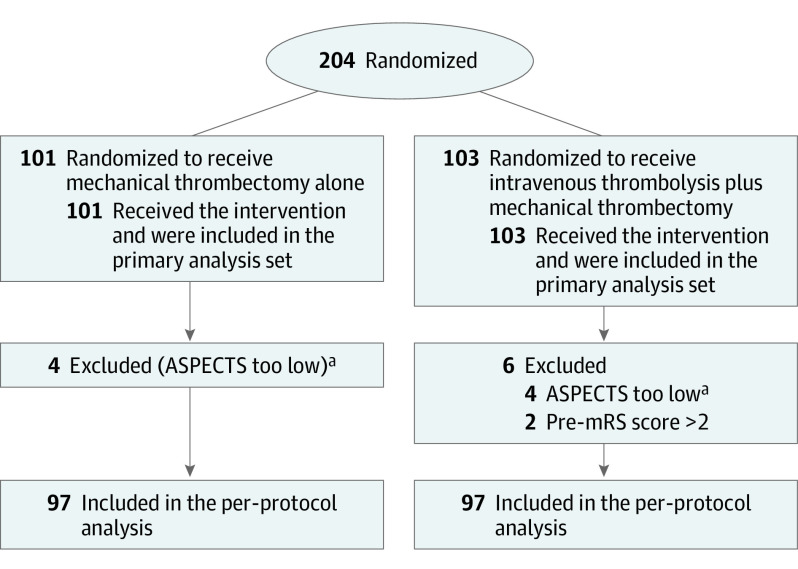

From January 2017 through July 2019, 204 patients were enrolled. The median age was 74 years, 128 (62.7%) were men, and the median NIHSS score was 18 (interquartile range [IQR], 12-23) (Table 1). At admission, 181 (88.7%) and 23 (11.3%) patients were assessed by MRI/MRA and CT/CTA, respectively. The median ASPECTS was 8 (IQR, 6-9) and the occluded vessel site was ICA in 77 patients (37.7%), M1 proximal in 37 (18.1%), and M1 distal in 90 (44.1%). Patients were randomized into 2 groups: 101 (49.5%) in the mechanical thrombectomy alone group and 103 (50.5%) in the combined intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy group. Ten patients did not fulfill the inclusion criteria (2 patients had a poor mRS score and 8 had a low ASPECTS. Therefore, 194 patients (97 in each group) were included in the per-protocol analysis (Figure 1). No baseline covariate or outcome data were missing, except for 12 cases (5.9%) for modified Mori grade. Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline according to group.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Patients at Baseline.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical thrombectomy alone (n = 101) | Intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy (n = 103) | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 74 (67-80) | 76 (67-80) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 56 (55) | 72 (70) |

| Female | 45 (45) | 31 (30) |

| Weight, median (IQR), kg | 59 (52-66) | 60 (53-68) |

| Medical historya | ||

| Hypertension | 61 (60) | 61 (59) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 57 (56) | 64 (62) |

| Smoking | 42 (42) | 54 (52) |

| Dyslipidemia | 30 (30) | 37 (36) |

| Diabetes | 16 (16) | 17 (17) |

| Past stroke | 12 (12) | 14 (14) |

| Past cardiovascular disease | 7 (7) | 7 (7) |

| Antiplatelet agent | 16 (16) | 18 (17) |

| Anticoagulant agent | 19 (19) | 17 (17) |

| Blood glucose level at admission, mean (SD), mg/dL | 135 (48) | 135 (52) |

| TOAST classificationb | ||

| Large artery (atherosclerosis) | 21 (21) | 15 (15) |

| Cardioembolism | 67 (66) | 72 (70) |

| Other determined/undetermined etiology | 13 (13) | 16 (16) |

| Blood pressure at admission, median (IQR), mm Hg | ||

| Systolic | 158 (132-172) | 150 (134-171) |

| Diastolic | 83 (75-98) | 86 (78-98) |

| NIHSS score at admission, median (IQR)c | 19 (13-23) | 17 (12-22) |

| Examination at admission | ||

| MRI/MRA | 86 (85) | 95 (92) |

| CT/CTA | 15 (15) | 8 (8) |

| Occluded site by MRA/CTA | ||

| ICA | 41 (41) | 36 (35) |

| M1 proximald | 19 (19) | 18 (17) |

| M1 distal | 41 (41) | 49 (48) |

| Occluded site by DSA | ||

| None | 1 (1) | 0 |

| ICA origin | 13 (13) | 16 (16) |

| ICA C4-5 | 6 (6) | 6 (6) |

| ICA C1-3 | 17 (17) | 14 (14) |

| M1 proximald | 10 (10) | 12 (12) |

| M1 distal | 44 (44) | 35 (34) |

| M2 | 10 (10) | 20 (19) |

| ASPECTSe | 7 (6-9) | 8 (6-9) |

| ASPECTS of 0-4 | 4 (4) | 4 (4) |

| Tandem lesionf | 9 (9) | 13 (13) |

| Modified Rankin Scale score before stroke | ||

| 0 | 84 (83) | 88 (85) |

| 1 | 11 (11) | 6 (6) |

| 2 | 6 (6) | 7 (7) |

| 3 | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Onset-to-door time, mean (SD), min | 92 (57) | 100 (55) |

| Door-to-randomization time, mean (SD), min | 37 (23) | 36 (19) |

| Randomization–to–rt-PA time, mean (SD), min | 14 (10) | |

| Randomization-to-puncture time, mean (SD), min | 20 (20) | 22 (16) |

| First procedural characteristics | ||

| Clot retrieval by stent | 58 (57) | 59 (57) |

| Aspiration | 34 (34) | 30 (30) |

| Intra-arterial thrombolysis | 1 (1) | 0 |

Abbreviations: ASPECTS, Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score; CT, computed tomography; CTA, computed tomographic angiography; DSA, digital subtraction angiography; ICA, internal carotid artery; IQR, interquartile range; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; M1, segment of the middle cerebral artery; M2, segment of the middle cerebral artery; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; rt-PA, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator; TOAST, Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment for stroke type.

SI conversion factor: To convert glucose to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0555.

Medical history was based on self-report, with the exception of the presence of atrial fibrillation, which was based on medical history and findings on electrocardiography performed at admission.

The TOAST classification23 denotes 5 subtypes of ischemic stroke: (1) large-artery atherosclerosis, (2) cardioembolism, (3) small vessel occlusion, (4) stroke of other determined etiology, and (5) stroke of undetermined etiology. The TOAST classification was based on clinical information and the radiological findings of MRI/CT.

Scores on the NIHSS range from 0 to 42, with higher scores indicating more severe neurologic deficits.

M1 proximal occlusion is defined as occlusion within 5 mm from bifurcation according to a previous study.17

Scores on the ASPECTS range from 0 to 10, with lower scores indicating more severe ischemic core lesion.

Cases in which an extracranial internal carotid occlusive lesion accompanied the intracranial lesion.

Figure 1. Flowchart of Enrollment, Randomization, and Treatment of the SKIP Randomized Clinical Trial.

Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to the mechanical thrombectomy alone group or the intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy group using a permuted block design stratified by site. Each site was not required to provide screening logs during the recruitment phase. Thus, the number of patients assessed for eligibility is not available. ASPECTS indicates Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score; mRS, modified Rankin Scale.

aASPECTS too low indicates ASPECTS less than 5 on initial diffusion-weighted imaging or less than 6 on initial computed tomography.

Endovascular Therapy

Five patients did not undergo mechanical thrombectomy because of aortic dissection (n = 2) and impossibility of approach (n = 1) in the mechanical thrombectomy alone group and because of spontaneous recanalization (n = 1) and impossibility of approach (n = 1) in the combined group. Therefore, 199 patients (97.5%) underwent mechanical thrombectomy. The median door-to-randomization time was 33 minutes (IQR, 23-48), randomization-to-puncture time was 18 minutes (IQR, 11-25), and puncture-to-reperfusion time was 34 minutes (IQR, 22-55). The randomization-to-puncture time was not statistically significantly different between the 2 groups (mechanical thrombectomy alone vs intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy: 16 minutes [IQR, 11-24] vs 19 minutes [13-27], P = .38). In the combined group, the puncture was performed before the administration of rt-PA in 22 patients (21.4%). The rate of clot migration was not significantly different between the 2 groups (25/100 [25%] vs 28/103 [27%], P > .99).

Primary Outcome

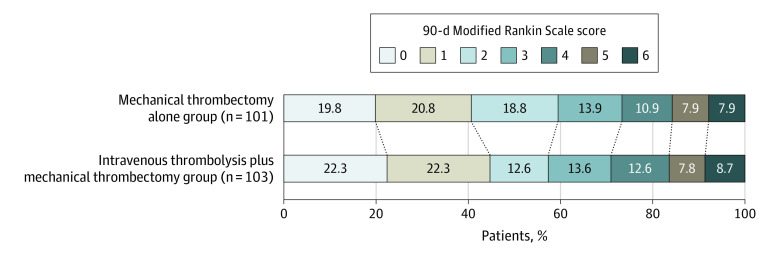

In the primary analysis set, a favorable outcome was observed in 60 of 101 patients (59.4%) in the mechanical thrombectomy alone group and in 59 of 103 (57.3%) in the combined group (difference, 2.1% [1-sided 97.5% CI, –11.4% to ∞]; odds ratio, 1.09 [1-sided 97.5% CI, 0.63 to ∞]; 1-sided noninferiority P = .18). Therefore, noninferiority of mechanical thrombectomy alone to combined intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy was not proven (Table 2 and Figure 2). In the per-protocol analysis, a favorable outcome was observed in 59 of 97 patients (60.8%) in the mechanical thrombectomy alone group and in 57 of 97 (58.8%) in the combined group, and noninferiority of the primary outcome measure was not proven (difference, 2.1% [1-sided 97.5% CI, –13.7% to ∞]; odds ratio, 1.06 [1-sided 97.5% CI, 0.60 to ∞]; P = .22).

Table 2. Primary and Secondary Efficacy End Points and Adverse Eventsa.

| Mechanical thrombectomy alone (n = 101) | Intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy (n = 103) | Noninferiority analysis | Superiority analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate of difference, % (97.5% 1-sided CI) | Odds ratio (97.5% 1-sided CI)b | P valuec | Estimate of difference, % (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P valuec | |||

| Primary outcome | ||||||||

| Modified Rankin Scale score 0-2 at 90 d, No. (%) | 60 (59.4) | 59 (57.3) | 2.1 (–11.4 to ∞) | 1.09 (0.63 to ∞) | .18 | |||

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||||

| Modified Rankin Scale score reduction (shift analysis) | 0.97 (0.60 to ∞) | .27 | ||||||

| Mortality at 90 d, No. (%) | 8 (7.9) | 9 (8.7) | –0.8 (–9.5 to 7.8) | 0.90 (0.33 to 2.43) | >.99 | |||

| TICI grade ≥2b, No. (%)d | 91 (90.1) | 96 (93.2) | –3.1 (–11.8 to 5.6) | 0.66 (0.24 to 1.82) | .46 | |||

| Adverse event outcomes | ||||||||

| Any ICH at 36 h from onset, No. (%) | 34 (33.7) | 52 (50.5) | –16.8 (–32.1 to –1.6) | 0.50 (0.28 to 0.88) | .02 | |||

| Symptomatic ICH (NINDS criteria) at 36 h from onset, No. (%)e | 8 (7.9) | 12 (11.7) | –3.7 (–13.0 to 5.6) | 0.65 (0.25 to 1.67) | .48 | |||

| Symptomatic ICH (SIT-MOST criteria) at 36 h from onset, No. (%)f | 6 (5.9) | 8 (7.8) | –1.8 (–9.7 to 6.1) | 0.75 (0.25 to 2.24) | .78 | |||

Abbreviations: ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; NINDS, National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke; SITS-MOST, Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-Monitoring Study; TICI, Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction.

All analyses were conducted using the primary analysis set.

The noninferiority margin was an odds ratio of 0.74.

P values refer to the comparison between mechanical thrombectomy alone and intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy.

The TICI grading system was based on the angiographic appearances of the treated occluded vessel and its distal branches: scores on the TICI grade range from 0 to 3, with 0 indicating no perfusion; 1, penetration with minimal perfusion; 2a, only partial filling (<50%) of the entire vascular territory; 2b, partial filling (≥50%); 2c, near complete perfusion with the exception of slow flow or a few distal cortical emboli; and 3, complete perfusion.

Symptomatic ICH was also assessed according to NINDS trial criteria: any intracerebral hemorrhage with neurologic deterioration from baseline (increase of ≥1 in the NIHSS score) or death within 36 hours.

The main definition of symptomatic ICH was the definition from the SITS-MOST: a large local or remote parenchymal ICH (>30% of the infarcted area affected by hemorrhage with a mass effect or extension outside the infarct) in combination with neurologic deterioration from baseline (increase of ≥4 in the NIHSS score) or death within 36 hours.

Figure 2. Functional Outcomes at 90 Days From Onset According to the Modified Rankin Scale Score.

Scores on the modified Rankin Scale range from 0 to 6, with 0 indicating no symptoms; 1, symptoms without clinical disability; 2, slight disability; 3, moderate disability; 4, moderately severe disability; 5, severe disability; and 6, death.

Secondary Outcome

In the primary analysis set, we analyzed the overall distribution of the mRS score at 90 days (shift analysis of the disability level). Mechanical thrombectomy alone was not associated with a favorable shift in the distribution of the mRS score at 90 days (odds ratio, 0.97 [1-sided 97.5% CI, 0.60 to ∞]; noninferiority P = .27), without any violation of the proportional odds assumption (Brant test P = .90). The number of deaths within 90 days after onset was 8 (7.9%) in the mechanical thrombectomy alone group and 9 (8.7%) in the combined group (difference, –0.8% [95% CI, –9.5% to 7.8%]; odds ratio, 0.90 [95% CI, 0.33 to 2.43]; P > .99). The 2 groups did not significantly differ in rates of successful reperfusion after mechanical thrombectomy, defined as eTICI grade of 2b or greater (91 [90.1%] vs 96 [93.2%]; difference, –3.1% [95% CI, –11.8% to 5.6%]; odds ratio, 0.66 [95% CI, 0.24 to 1.82]; P = .46) (Table 2). Other prespecified secondary outcome data are described in the eTable in Supplement 3.

Adverse Events

Intracerebral hemorrhage was assessed by only CT at 36 hours from onset. Of 86 patients with intracerebral hemorrhage, 16 patients showed parenchymal hematoma 2 defined by European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study criteria. The rate of any intracerebral hemorrhage at 36 hours from onset was lower in the mechanical thrombectomy alone group than in the combined group (34 [33.7%] vs 52 [50.5%]; difference, –16.8% [95% CI, –32.1% to –1.6%]; odds ratio, 0.50 [95% CI, 0.28 to 0.88]; P = .02). However, the rate of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage was not significantly different between the 2 groups, based on the NINDS criteria (8 [7.9%] vs 12 [11.7%]; difference, –3.7% [ 95% CI, –13.0% to 5.6%]; odds ratio, 0.65 [95% CI, 0.25 to 1.67]; P = .48) and the SIT-MOST criteria (6 [5.9%] vs 8 [7.8%]; difference, –1.8% [95% CI, –9.7% to 6.1%]; odds ratio, 0.75 [95% CI, 0.25 to 2.24]; P = .78). In the post hoc analysis, patients with any intracerebral hemorrhage (symptomatic [n = 14] and asymptomatic [n = 72]) had less frequently favorable outcomes than those without intracerebral hemorrhage (41.9% [36/86] vs 70.3% [83/118], P < .001). The incidence of other hemorrhagic events was not significantly different (1/101 [1%] and 4/103 [4%], P = .37) (1 [1.0%] vs 4 [3.9%]; difference, –2.9% [95% CI, –0.08 to 0.02]; odds ratio, 0.25 [95% CI, 0.03 to 2.25]; P = .37) between the 2 groups.

Subgroup Analysis and Post Hoc Analyses

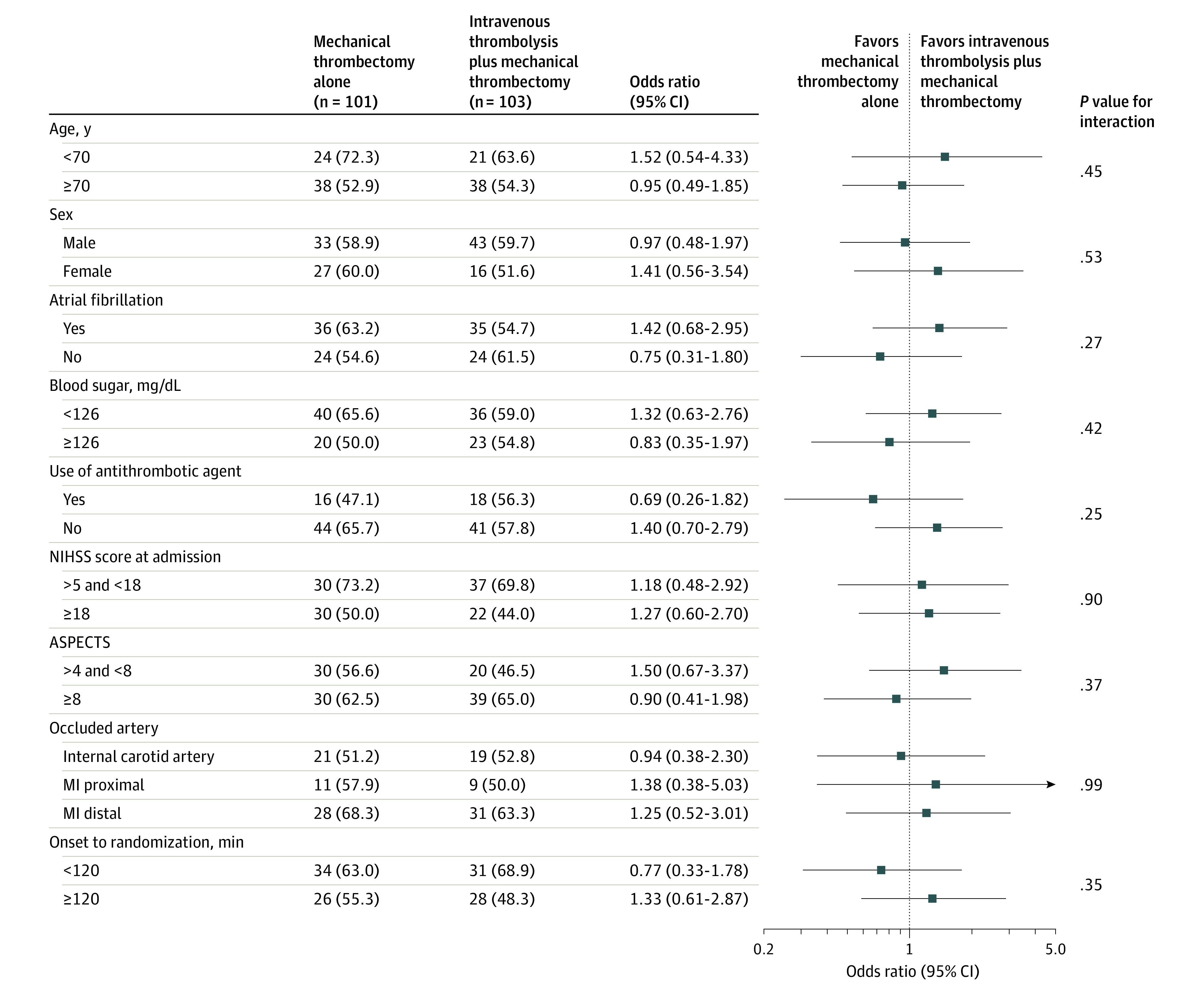

There was no significant heterogeneity of effect on the primary outcome across the post hoc subgroups: age, sex, atrial fibrillation, blood glucose, antithrombotic agent, NIHSS score, ASPECTS, occluded artery at admission, and onset randomization time (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Subgroup Plot Showing the Adjusted Treatment Effect for Favorable Outcome, With P Values for Heterogeneity Across Subgroups.

ASPECTS indicates Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score; M1, middle cerebral artery M1 segment; and NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. To convert glucose to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0555.

The results for the primary outcome of the post hoc mixed-effect logistic regression analysis with study site as a random effect were similar (odds ratio, 1.09 [1-sided 97.5% CI, 0.63 to ∞]; noninferiority P = .17).

Discussion

This clinical trial of patients with acute large vessel occlusion stroke failed to demonstrate noninferiority of mechanical thrombectomy alone compared with combined intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy with regard to favorable functional outcome. Although this study hypothesis could not be proved, the point estimates of treatment effect for mechanical thrombectomy alone was nominally slightly better, not worse, compared with combined therapy. Accordingly, a larger trial or meta-analysis of trials is needed to conclusively assess noninferiority.

Recent studies have evaluated the effectiveness of mechanical thrombectomy therapy compared with that for combined intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy therapy in patients with acute large vessel occlusion stroke.1,5,12,13,22,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31 A meta-analysis demonstrated that combined intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy therapy was associated with a higher likelihood of functional independence compared with that for mechanical thrombectomy alone therapy (odds ratio, 1.52 [95% CI, 1.32 to 1.76]).32 However, these results were obtained from retrospective cohort studies, in which mechanical thrombectomy alone was performed on many rt-PA–ineligible patients.33 In contrast, Kaesmacher et al34 reported that a meta-analysis using only rt-PA–eligible patients could not conclude that mechanical thrombectomy alone had more favorable outcome compared with combined intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy.

This study demonstrated that any intracerebral hemorrhage within 36 hours from onset was significantly lower in the mechanical thrombectomy alone group than in the combined group. However, symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage did not significantly differ between the 2 groups. Intracerebral hemorrhage is associated with high morbidity and mortality after mechanical thrombectomy therapy.35 Administration of rt-PA alone is known to increase the rate of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage 3- to 10-fold vs that with controls, though absolute numbers were low.14,20 In this trial, the incidence of any intracerebral hemorrhage was significantly higher in the combined group than in the mechanical thrombectomy alone group. The higher frequency of any intracerebral hemorrhage may be caused by the administration of rt-PA. Many reports have shown that symptomatic, but not asymptomatic, intracerebral hemorrhage is associated with poor outcomes.36,37,38 Van Kranendonk et al39 reported that any intracerebral hemorrhage has a potential for poor outcome. In the post hoc analysis of this study, favorable outcomes were significantly less frequent in patients with any intracerebral hemorrhage than in those without intracerebral hemorrhage. Further studies are needed to clarify the relationship between any intracerebral hemorrhage and patient outcome.

The combined intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy therapy might be considered to be disadvantaged by the delayed start of mechanical thrombectomy due to the preparation of rt-PA administration. However, the randomization-to-puncture time was not statistically significantly different between the 2 groups. In 22 cases (21.4%) in the combined group, groin puncture occurred before the start of intravenous thrombolysis. Therefore, rt-PA administration might be not a disadvantage to the starting of mechanical thrombectomy therapy.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, this was an open-label study regarding the use of rt-PA. Second, the sample size and the noninferiority margin of 0.74 were calculated from previous studies using a dose of 0.9 mg/kg of alteplase. In addition, the noninferiority margin was selected using the fixed-margin method rather than the minimal clinically important difference. Third, favorable outcomes were more frequent than expected, which may have resulted in a reduction of study power. Recently, the Direct-MT trial40 in China, which was a similar randomized clinical trial to this trial, demonstrated noninferiority for mechanical thrombectomy alone compared with combined intravenous thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy with regard to functional outcome. In addition, 3 randomized clinical trials (MR CLEAN-NO IV [ISRCTN80619088], SWIFT DIRECT [NCT03192332], and DIRECT-SAFE [NCT03494920]) similar to this trial are ongoing. Meta-analyses that include these trials may provide greater clarity.

Conclusions

Among patients with acute large vessel occlusion stroke, mechanical thrombectomy alone, compared with combined intravenous thrombolysis plus mechanical thrombectomy, failed to demonstrate noninferiority regarding favorable functional outcome. However, the wide confidence intervals around the effect estimate also did not allow a conclusion of inferiority.

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eBox 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria of the SKIP Study

eBox 2. Prespecified Outcome Measures in the SKIP Study

eTable. Primary and Secondary Efficacy Endpoints and Adverse Events

eAppendix. SKIP Study Investigators

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Jovin TG, Chamorro A, Cobo E, et al. ; REVASCAT Trial Investigators . Thrombectomy within 8 hours after symptom onset in ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(24):2296-2306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berkhemer OA, Fransen PS, Beumer D, et al. ; MR CLEAN Investigators . A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(1):11-20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell BC, Mitchell PJ, Kleinig TJ, et al. ; EXTEND-IA Investigators . Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke with perfusion-imaging selection. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(11):1009-1018. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A, et al. ; SWIFT PRIME Investigators . Stent-retriever thrombectomy after intravenous t-PA vs t-PA alone in stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(24):2285-2295. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1415061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, et al. ; ESCAPE Trial Investigators . Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(11):1019-1030. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bracard S, Ducrocq X, Mas JL, et al. ; THRACE investigators . Mechanical thrombectomy after intravenous alteplase versus alteplase alone after stroke (THRACE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(11):1138-1147. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30177-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muir KW, Ford GA, Messow CM, et al. ; PISTE Investigators . Endovascular therapy for acute ischaemic stroke: the Pragmatic Ischaemic Stroke Thrombectomy Evaluation (PISTE) randomised, controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(1):38-44. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2016-314117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP Jr, et al. ; American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Clinical Cardiology . Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44(3):870-947. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e318284056a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turc G, Bhogal P, Fischer U, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO)—European Society for Minimally Invasive Neurological Therapy (ESMINT) Guidelines on Mechanical Thrombectomy in Acute Ischaemic StrokeEndorsed by Stroke Alliance for Europe (SAFE). Eur Stroke J. 2019;4(1):6-12. doi: 10.1177/2396987319832140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toyoda K, Koga M, Iguchi Y, et al. Guidelines for intravenous thrombolysis (recombinant tissue–type plasminogen activator), the third edition, March 2019: a guideline from the Japan Stroke Society. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2019;59(12):449-491. doi: 10.2176/nmc.st.2019-0177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, et al. ; HERMES collaborators . Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet. 2016;387(10029):1723-1731. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00163-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broeg-Morvay A, Mordasini P, Bernasconi C, et al. Direct mechanical intervention versus combined intravenous and mechanical intervention in large artery anterior circulation stroke: a matched-pairs analysis. Stroke. 2016;47(4):1037-1044. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mistry EA, Mistry AM, Nakawah MO, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy outcomes with and without intravenous thrombolysis in stroke patients: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2017;48(9):2450-2456. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.017320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hacke W, Donnan G, Fieschi C, et al. ; ATLANTIS Trials Investigators; ECASS Trials Investigators; NINDS rt-PA Study Group Investigators . Association of outcome with early stroke treatment: pooled analysis of ATLANTIS, ECASS, and NINDS rt-PA stroke trials. Lancet. 2004;363(9411):768-774. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15692-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki K, Kimura K, Takeuchi M, et al. The randomized study of endovascular therapy with versus without intravenous tissue plasminogen activator in acute stroke with ICA and M1 occlusion (SKIP study). Int J Stroke. 2019;14(7):752-755. doi: 10.1177/1747493019840932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamaguchi T, Mori E, Minematsu K, et al. ; Japan Alteplase Clinical Trial (J-ACT) Group . Alteplase at 0.6 mg/kg for acute ischemic stroke within 3 hours of onset: Japan Alteplase Clinical Trial (J-ACT). Stroke. 2006;37(7):1810-1815. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000227191.01792.e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirano T, Sasaki M, Mori E, Minematsu K, Nakagawara J, Yamaguchi T; Japan Alteplase Clinical Trial II Group . Residual vessel length on magnetic resonance angiography identifies poor responders to alteplase in acute middle cerebral artery occlusion patients: exploratory analysis of the Japan Alteplase Clinical Trial II. Stroke. 2010;41(12):2828-2833. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.594333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goyal M, Fargen KM, Turk AS, et al. 2C or not 2C: defining an improved revascularization grading scale and the need for standardization of angiography outcomes in stroke trials. J Neurointerv Surg. 2014;6(2):83-86. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2013-010665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mori E, Minematsu K, Nakagawara J, Yamaguchi T, Sasaki M, Hirano T; Japan Alteplase Clinical Trial II Group . Effects of 0.6 mg/kg intravenous alteplase on vascular and clinical outcomes in middle cerebral artery occlusion: Japan Alteplase Clinical Trial II (J-ACT II). Stroke. 2010;41(3):461-465. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.573477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(24):1581-1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wahlgren N, Ahmed N, Dávalos A, et al. ; SITS-MOST investigators . Thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke in the Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-Monitoring Study (SITS-MOST): an observational study. Lancet. 2007;369(9558):275-282. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60149-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weber R, Nordmeyer H, Hadisurya J, et al. Comparison of outcome and interventional complication rate in patients with acute stroke treated with mechanical thrombectomy with and without bridging thrombolysis. J Neurointerv Surg. 2017;9(3):229-233. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2015-012236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams HP Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke: definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial: TOAST, Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke. 1993;24(1):35-41. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.24.1.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leker RR, Pikis S, Gomori JM, Cohen JE. Is bridging necessary? a pilot study of bridging versus primary stentriever-based endovascular reperfusion in large anterior circulation strokes. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24(6):1163-1167. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rai AT, Boo S, Buseman C, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis before endovascular therapy for large vessel strokes can lead to significantly higher hospital costs without improving outcomes. J Neurointerv Surg. 2018;10(1):17-21. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2016-012830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coutinho JM, Liebeskind DS, Slater LA, et al. Combined intravenous thrombolysis and thrombectomy vs thrombectomy alone for acute ischemic stroke: a pooled analysis of the SWIFT and STAR studies. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(3):268-274. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.5374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abilleira S, Ribera A, Cardona P, et al. ; Catalan Stroke Code and Reperfusion Consortium . Outcomes after direct thrombectomy or combined intravenous and endovascular treatment are not different. Stroke. 2017;48(2):375-378. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minnerup J, Wersching H, Teuber A, et al. ; REVASK Investigators . Outcome after thrombectomy and intravenous thrombolysis in patients with acute ischemic stroke: a prospective observational study. Stroke. 2016;47(6):1584-1592. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.012619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dávalos A, Pereira VM, Chapot R, Bonafé A, Andersson T, Gralla J; Solitaire Group . Retrospective multicenter study of Solitaire FR for revascularization in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2012;43(10):2699-2705. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.663328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mulder MJ, Berkhemer OA, Fransen PS, et al. ; MR CLEAN investigators . Treatment in patients who are not eligible for intravenous alteplase: MR CLEAN subgroup analysis. Int J Stroke. 2016;11(6):637-645. doi: 10.1177/1747493016641969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nogueira RG, Gupta R, Jovin TG, et al. Predictors and clinical relevance of hemorrhagic transformation after endovascular therapy for anterior circulation large vessel occlusion strokes: a multicenter retrospective analysis of 1122 patients. J Neurointerv Surg. 2015;7(1):16-21. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2013-010743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katsanos AH, Malhotra K, Goyal N, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis prior to mechanical thrombectomy in large vessel occlusions. Ann Neurol. 2019;86(3):395-406. doi: 10.1002/ana.25544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phan K, Dmytriw AA, Lloyd D, et al. Direct endovascular thrombectomy and bridging strategies for acute ischemic stroke: a network meta-analysis. J Neurointerv Surg. 2019;11(5):443-449. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-014260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaesmacher J, Mordasini P, Arnold M, et al. Direct mechanical thrombectomy in tPA-ineligible and -eligible patients versus the bridging approach: a meta-analysis. J Neurointerv Surg. 2019;11(1):20-27. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-013834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fiorelli M, Bastianello S, von Kummer R, et al. Hemorrhagic transformation within 36 hours of a cerebral infarct: relationships with early clinical deterioration and 3-month outcome in the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study I (ECASS I) cohort. Stroke. 1999;30(11):2280-2284. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.30.11.2280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molina CA, Alvarez-Sabín J, Montaner J, et al. Thrombolysis-related hemorrhagic infarction: a marker of early reperfusion, reduced infarct size, and improved outcome in patients with proximal middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke. 2002;33(6):1551-1556. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000016323.13456.E5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dzialowski I, Pexman JH, Barber PA, Demchuk AM, Buchan AM, Hill MD; CASES Investigators . Asymptomatic hemorrhage after thrombolysis may not be benign: prognosis by hemorrhage type in the Canadian alteplase for stroke effectiveness study registry. Stroke. 2007;38(1):75-79. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000251644.76546.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lei C, Wu B, Liu M, Chen Y. Asymptomatic hemorrhagic transformation after acute ischemic stroke: is it clinically innocuous? J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23(10):2767-2772. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Kranendonk KR, Treurniet KM, Boers AMM, et al. ; MR CLEAN investigators . Hemorrhagic transformation is associated with poor functional outcome in patients with acute ischemic stroke due to a large vessel occlusion. J Neurointerv Surg. 2019;11(5):464-468. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-014141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang P, Zhang Y, Zhang L, et al. ; DIRECT-MT Investigators . Endovascular Thrombectomy with or without Intravenous Alteplase in Acute Stroke. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):1981-1993. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eBox 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria of the SKIP Study

eBox 2. Prespecified Outcome Measures in the SKIP Study

eTable. Primary and Secondary Efficacy Endpoints and Adverse Events

eAppendix. SKIP Study Investigators

Data Sharing Statement