Key Points

Question

What are the short-term effects of atabecestat in preclinical Alzheimer disease (AD), and are adverse effects reversible after stopping treatment?

Findings

In this truncated randomized clinical trial of 557 participants with preclinical AD, atabecestat treatment was associated with statistically significant greater, dose-related cognitive worsening and neuropsychiatric adverse events (AEs) vs placebo. Baseline to last off-treatment cognitive assessment suggested return to baseline cognitive status, and frequency of neuropsychiatric AEs returned to placebo levels after stopping atabecestat.

Meaning

This study’s findings confirm dose-related worsening of cognition and neuropsychiatric AEs in atabecestat-treated participants, with recovery after up to 6 months off treatment.

Abstract

Importance

Atabecestat, a nonselective oral β-secretase inhibitor, was evaluated in the EARLY trial for slowing cognitive decline in participants with preclinical Alzheimer disease. Preliminary analyses suggested dose-related cognitive worsening and neuropsychiatric adverse events (AEs).

Objective

To report efficacy, safety, and biomarker findings in the EARLY trial, both on and off atabecestat treatment, with focus on potential recovery of effects on cognition and behavior.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b/3 study conducted from November 2015 to December 2018 after being stopped prematurely. The study was conducted at 143 centers across 14 countries. Participants were permitted to be followed off-treatment by the original protocol, collecting safety and efficacy data. From 4464 screened participants, 557 amyloid-positive, cognitively normal (Clinical Dementia Rating of 0; aged 60-85 years) participants (approximately 34% of originally planned 1650) were randomized before the trial sponsor stopped enrollment.

Interventions

Participants were randomized (1:1:1) to atabecestat, 5 mg (n = 189), 25 mg (n = 183), or placebo (n = 185).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcome: change from baseline in Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite score. Secondary outcomes: change from baseline in the Cognitive Function Index and the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status total scale score. Safety was monitored throughout the study.

Results

Of 557 participants, 341 were women (61.2%); mean (SD) age was 70.4 (5.56) years. In May 2018, study medication was stopped early owing to hepatic-related AEs; participants were followed up off-treatment for 6 months. Atabecestat, 25 mg, showed significant cognitive worsening vs placebo for Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite at month 6 (least-square mean difference, −1.09; 95% CI, −1.66 to −0.53; P < .001) and month 12 (least-square mean, −1.62; 95% CI, −2.49 to −0.76; P < .001), and at month 3 for Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (least-square mean, −3.70; 95% CI, −5.76 to −1.63; P < .001). Cognitive Function Index participant report showed nonsignificant worsening at month 12. Systemic and neuropsychiatric-related treatment-emergent AEs were greater in atabecestat groups vs placebo. After stopping treatment, follow-up cognitive testing and AE assessment provided evidence of reversibility of drug-induced cognitive worsening and AEs in atabecestat groups.

Conclusions and Relevance

Atabecestat treatment was associated with dose-related cognitive worsening as early as 3 months and presence of neuropsychiatric treatment-emergent AEs, with evidence of reversibility after 6 months off treatment.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02569398

This randomized clinical trial evaluates the short-term effects of atabecestat in preclinical Alzheimer disease.

Introduction

β-Site amyloid precursor protein (APP)–cleaving enzyme-1, or β-secretase-1 (BACE-1), controls the rate-limiting step in the generation of amyloid-β (Aβ) from APP. Early intervention with a BACE-1 inhibitor (BACEi) represents a promising therapeutic approach to slow progression of Alzheimer disease (AD), particularly at the stage of preclinical AD when accumulation of Aβ is accelerating, prior to extensive, irreversible neurodegeneration.1

Atabecestat, a nonselective oral BACE-1 and BACE-2 inhibitor, was in development by Janssen Research & Development LLC and Shionogi and Co Ltd for treating AD. Atabecestat demonstrated significant median reductions from baseline (averaged over 24 hours, at steady state; see the trial protocol in Supplement 1) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Aβ1-40 of approximately 52% and 84% at doses of 5 mg and 25 mg daily, respectively.2 The EARLY phase 2b/3 confirmatory registration trial was conducted to evaluate efficacy and safety of atabecestat for slowing cognitive decline in preclinical AD. A longitudinal extension phase 2 study was ongoing in parallel to EARLY.3

In May 2018, based on significant dose-related liver enzyme elevations in participants receiving atabecestat in both studies, Janssen Research & Development concluded the benefit/risk was no longer favorable for atabecestat; hence, randomization and dosing were terminated before enrollment completion.

A preliminary analysis of this trial (before completing the off-drug safety follow-up phase) revealed a small but consistent dose-related cognitive worsening, evident at first postbaseline assessment at 3 months.4 Other BACEis reported similar findings.5,6 Here, we report final clinical, safety, and biomarker data, both on and off atabecestat treatment, in the EARLY trial, focusing on potential recovery of adverse effects.

Methods

Participants

Clinically normal (Clinical Dementia Rating [CDR] global score of 0 and generally healthy) participants aged between 60 and 85 years with/without subjective memory difficulties were enrolled. Participants with elevated brain amyloid, as demonstrated by either CSF or amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) scan at screening, were eligible (eMethods 1 in Supplement 2). Exclusions included treatment with acetyl-cholinesterase-inhibitor or memantine, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or physical evidence of substantial/unstable disease (eMethods 2 in Supplement 2).

Study Design, Randomization, and Blinding

This global (143 sites), double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b/3 study aimed to enroll 1650 participants. Study protocol/amendments (Supplement 1) were approved by institutional review boards at all study sites. All participants provided written informed consent.

Participants were originally randomized (1:1:1) to atabecestat, 10 mg or 25 mg once daily, or placebo. Owing to dose-related hepatic enzyme elevations, the 10-mg dose was reduced to 5 mg, maintaining the blind; 11 participants received 10 mg before this amendment. Thereafter, participants were randomized (1:1:1) to atabecestat, 5 mg or 25 mg, or placebo. Randomization was stratified by apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 carrier status (carrier/noncarrier) and country. Blinding for study drug assignment was maintained until the database was finalized after trial termination.

Study Assessments

Screening included 4 steps assessing participants’ general health, clinical scales, brain MRI, and amyloid status. Clinical assessments and MRI were subsequently evaluated every 6 months following randomization (schedule of events can be found in the trial protocol in Supplement 1).

The original protocol permitted following participants after stopping the study drug to continue to assess safety and efficacy outcomes. After discontinuation of atabecestat, all willing participants were followed up off-treatment for up to an additional 6 months, according to the original protocol schedule of activities. To reduce participant burden, priority was given to safety and primary/key secondary outcomes. Blinding to original treatment assignment was maintained. Because participants varied in their time in the study since randomization, the on-treatment and off-treatment evaluations as well as on-treatment exposure and off-treatment observation times were variable (eMethods 3 in Supplement 2).

Efficacy Assessments

The primary end point was change from baseline in the Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite (PACC) score7,8 and on-treatment data reported to month 18. The PACC score was defined as the sum of transformed z scores for each of the 4 components of the measure. The PACC was administered during screening, at baseline, and every 6 months after baseline with alternating versions.

The key secondary outcome was the Cognitive Function Index (CFI), a participant-reported and study partner-reported outcome measure that includes 15 questions (14 contribute to the total score).9,10 The CFI was assessed at baseline and every 12 months following randomization and assessed perceived ability to perform high-level functional tasks in daily life and sense of overall cognitive function. Participants and study partners independently rated participant function.

Cognition was additionally assessed by change from baseline in the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS)11 total scale score; on-treatment data were reported to month 15. The RBANS was administered during screening, at 3 months after randomization, and every 6 months after in alternating versions.

Other efficacy measures reported include assessment of functional performance using AD Cooperative Study Activities of Daily Living-Prevention Instrument (ADCS-ADL-PI), clinical status using CDR sum of boxes (CDR-SB), and global score. Additional secondary objectives include analyses of baseline to last on-treatment PACC total score, RBANS total score, individual components of the PACC and RBANS, and participant-rated and study partner–rated CFI change from baseline to 12 months taking study medication. The PACC and RBANS had enough posttreatment evaluations to be analyzed for potential recovery of cognitive worsening. Average exposure time on-treatment and observation time off-treatment were analyzed.

Safety Assessments

Safety and tolerability were monitored throughout the study, including incidence, severity, and type of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), weight and vital sign measurements, serial MRIs, and clinical laboratory results. For TEAEs more frequently observed during atabecestat treatment, frequency off-treatment was reported.

Imaging and Biomarkers

Exploratory end points with available data included brain volume measurement by volumetric MRI (vMRI) and markers of tau (phosphorylated-tau [p181tau]) and neurodegeneration (neurofilament light chain [NfL], total-tau [t-tau]) in CSF. Correlation between change in biomarkers (vMRI, CSF t-tau or p181tau, and NfL) and change in cognition was also analyzed.

Statistical Analysis

Assuming 2-sided type I error of 0.05, maximum 30% attrition, and an SD of 2.44 PACC units, randomization of 1650 participants was planned to provide 80% power to detect 35% slowing of cognitive change (approximately 0.49 PACC units). Due to early cessation of dosing, only 557 participants (34%) were randomized; 37% of these had a postbaseline PACC. Statistical analyses conducted are considered exploratory in nature and were performed at the .05 level of significance without adjustment for multiple comparisons.

The primary outcome measure (PACC) was analyzed using mixed-effects model-repeated measures (MMRM). The dependent variable was change from baseline for the PACC at each follow-up visit. Fixed terms for this model were treatment group, sex, country, APOE-ε4 carrier status, education level, PACC baseline score, age at study entry, average hippocampal volume at baseline, time (as a factor), and the interaction of treatment and time. Analyses of changes from baseline using a similar MMRM model were performed for the following: each PACC component and RBANS subtest, RBANS total scale, participant-reported and study partner–reported CFI total score, and ADCS-ADL-PI. Biomarker analyses were carried out for participants with at least 85% treatment compliance at the analysis time.

The TEAEs, serious TEAEs, and off-treatment AEs were summarized by system-organ class and preferred terms. The AEs with onset more than 7 days after the last dose were defined as off treatment. Safety evaluation also included assessment of laboratory tests, weight, and vital signs.

To explore the possibility of recovery from worsened cognitive performance after stopping atabecestat, 2 approaches were used. First, irrespective of exposure or observation time, observed PACC change before and after treatment discontinuation was summarized within each treatment group. Second, a linear mixed-effect model of PACC over time was fit with fixed effects, accounting for exposure and observation time. All statistical analyses were performed with R, version 3.4.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing), and results were reported as point estimates with appropriate estimates of variability.

Results

Participant Disposition

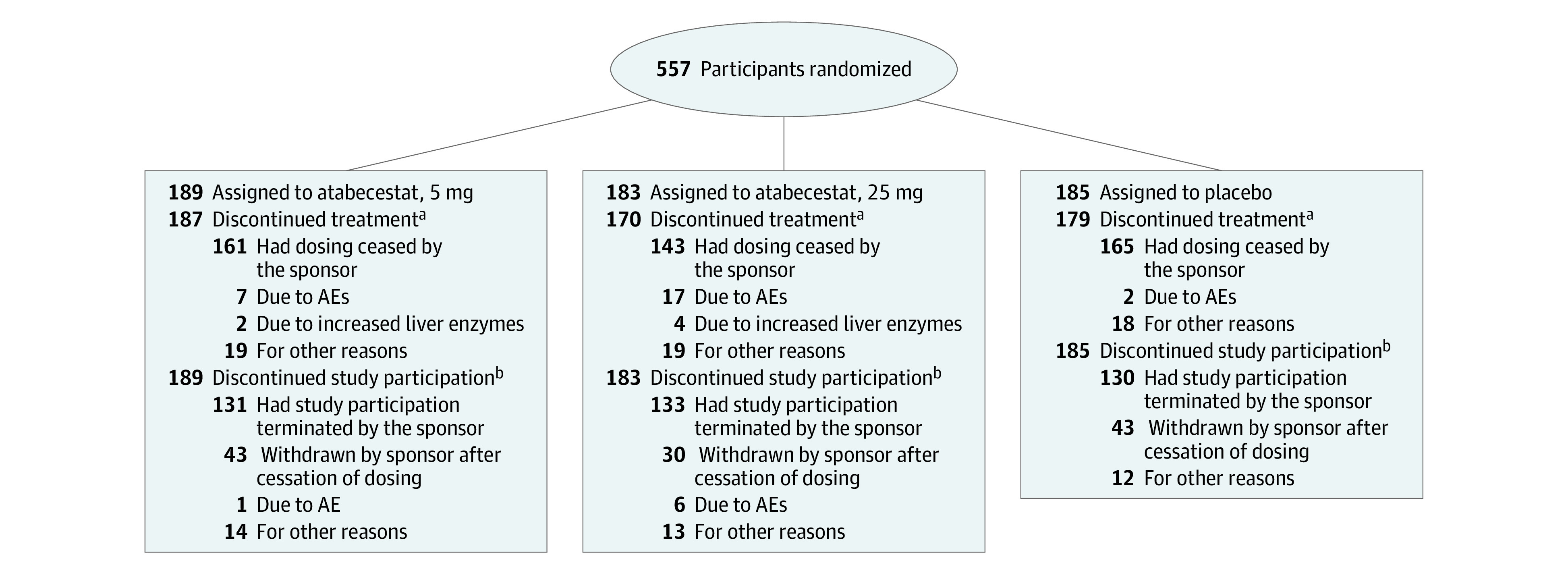

From November 23, 2015, to May 17, 2018, a total of 557 participants were randomized: 189 to atabecestat, 5 mg, 183 to atabecestat, 25 mg, and 185 to placebo. Demographic and baseline disease characteristics were generally well balanced across treatment groups for both ITT and on-treatment and off-treatment populations (Table 1; eTables 1 and 2 in Supplement 2). Most participants (n = 469; 84.2%) discontinued study medication owing to dosing cessation by the sponsor (Figure 1). Discontinuations owing to AEs and increased liver enzymes were more frequent in the atabecestat groups vs placebo (Figure 1).

Table 1. Demographics and Baseline Characteristics (ITT Analysis Set)a.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 185) | Atabecestat | ||

| 5 mg (n = 189) | 25 mg (n = 183) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 70.2 (5.81) | 70.6 (5.26) | 70.5 (5.62) |

| Age category, y | |||

| <65 | 33 (17.8) | 23 (12.2) | 30 (16.4) |

| 65-74 | 106 (57.3) | 121 (64.0) | 111 (60.7) |

| ≥75 | 46 (24.9) | 45 (23.8) | 42 (23.0) |

| Women | 108 (58.4) | 116 (61.4) | 117 (63.9) |

| Race | |||

| White | 167 (90.3) | 173 (91.5) | 168 (91.8) |

| Black or African American | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1.1) |

| Asian | 12 (6.5) | 11 (5.8) | 11 (6.0) |

| American Indian or Alaska native | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

| Other | 4 (2.2) | 3 (1.6) | 2 (1.1) |

| Ethnicityb | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 8 (4.3) | 6 (3.2) | 7 (3.8) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 176 (95.1) | 183 (96.8) | 176 (96.2) |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 16 (8.7) | 10 (5.3) | 14 (7.7) |

| High school and higher | 169 (91.4) | 179 (94.7) | 169 (92.3) |

| BMI | |||

| Mean (SD) | 26.9 (4.51) | 26.2 (4.27) | 26.7 (4.88) |

| Category | |||

| Normal, 18.5 to <25 | 70 (38.5) | 72 (38.5) | 75 (41.9) |

| Overweight, 25 to <30 | 70 (38.5) | 80 (42.8) | 67 (37.4) |

| Obese, ≥30 | 42 (23.1) | 32 (17.1) | 36 (20.1) |

| MMSE score, mean (SD) | 28.2 (1.81) | 28.3 (1.65) | 28.2 (1.65) |

| Scores | |||

| PACC | |||

| No. | 80 | 75 | 66 |

| Mean (SD) | −0.26 (3.00) | 0.16 (2.690) | −0.01 (2.840) |

| RBANS total | |||

| No. | 119 | 117 | 110 |

| Mean (SD) | 99.9 (13.69) | 101.1 (12.09) | 100.1 (13.60) |

| APOE ε4 carrier | 102 (55.1) | 108 (57.1) | 103 (56.3) |

| Adjusted baseline hippocampal volume, mean (SD) | 5634.0 (577.62) | 5631.7 (599.96) | 5666.9 (675.42) |

| CFI total score | |||

| Participant | |||

| No. | 178 | 184 | 181 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.9 (2.06) | 1.9 (2.01) | 1.7 (1.89) |

| Study partner | |||

| No. | 176 | 182 | 180 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.3 (1.90) | 1.1 (1.56) | 1.4 (1.98) |

Abbreviations: APOE ε4, apolipoprotein E ε4 allele; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CFI, cognitive function index; ITT, intention-to-treat; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; PACC, Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite; RBANS, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status.

One hundred forty-three centers; in the United States (61 centers), Japan (13 centers), Spain (12 centers), Australia (9 centers), Germany (9 centers), United Kingdom (8 centers), Italy (7 centers), Belgium (6 centers), Denmark (4 centers), the Netherlands (4 centers), Mexico (3 centers), Canada (2 centers), Finland (4 centers), and Sweden (1 center).

One patient from the placebo group was of unknown ethnicity.

Figure 1. Participant Disposition.

AE indicates adverse event.

aParticipants who discontinued study medication for other reasons before sponsor stopped atabecestat dosing.

bParticipants who discontinued the study. Participants could remain in the study after stopping study medication. Most study discontinuations were due to the sponsor stopping the study.

Most participants were women (n = 341; 61.2%), and the mean (SD) age was 70.4 (5.56) years. The study population was highly educated, and 55% to 57% carried at least 1 APOE4-ε4 allele. At the time study intervention was stopped, the median exposure duration was 21.1 weeks (interquartile range, 10.5-36.0); median follow-up off-treatment was 14.7 weeks (interquartile range, 9.9-16.7).

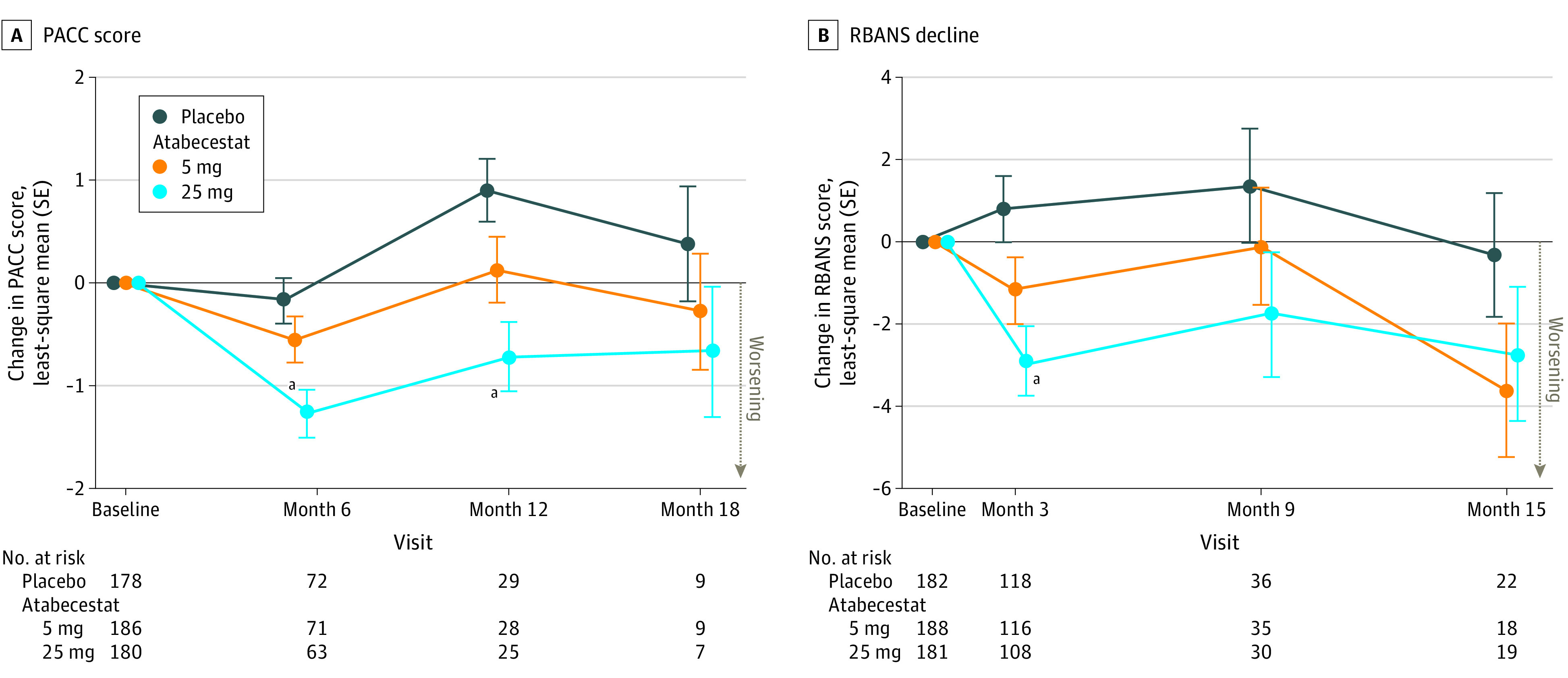

Cognitive Results

In MMRM analyses, at month 6, the least-square mean (LSM) differences of the PACC score for atabecestat, 5 mg and 25 mg, vs placebo, indicated worsening of cognitive performance: −0.38 (95% CI, −0.92 to 0.17; P = .17) and −1.09 (95% CI, −1.66 to −0.53; P <.001), respectively. The 12-month LSM differences were consistent: −0.79 (95% CI, −1.63 to 0.05; P = .06) for 5-mg atabecestat and −1.62 (95% CI, −2.49 to −0.76; P <.001) for 25-mg atabecestat (Figure 2A; eTable 3 in Supplement 2). Sensitivity analyses performed by removing participants with hepatic enzyme elevations (alanine aminotransferase [ALT] more than 3 times the upper limit of normal [ULN]), and those with neuropsychiatric AEs confirmed that neither the hepatic-related nor neuropsychiatric-related AEs fully accounted for the cognitive worsening (eTable 4 in Supplement 2). Analyses of the individual PACC components showed significantly worse cognitive performance in the atabecestat, 25 mg, group vs placebo at 6 months on all components except Mini-Mental State Examination (eTable 5 in Supplement 2).

Figure 2. Least-Square Mean (SE) Difference of Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite (PACC) (A) and Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) (B) Decline (Intention-to-Treat [ITT] Analysis Set).

A, PACC is defined as the sum of transformed z scores for each of the 4 components of the measure: sum of free and total recall on the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, Delayed Paragraph Recall score on Logical Memory from the Wechsler Memory Scale, Digit-Symbol Coding Subtest (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale IV); and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) total score. A decrease of 1 baseline standard deviation on each component would result in a 4-point decrease in the composite. B, RBANS consists of 12 subtests measuring the following 5 indices (domains): attention, language, visuospatial/construction, immediate memory, and delayed memory.

aP < .001.

Decline on RBANS total scale was also evident at first postbaseline assessment at 3 months (Figure 2B); LSM treatment differences were significant for the 25-mg group (−3.70; 95% CI −5.76 to −1.63; P <.001) and nonsignificant for the 5-mg group (−1.97; 95% CI, −3.99 to 0.05; P = .06). At months 9 and 15, nonsignificant negative LSM treatment differences were seen for both treatment groups. The MMRM analyses of individual RBANS subtests showed impaired performance on multiple subtests in atabecestat groups vs placebo, but no group differences were noted for any subtest (eTable 6 in Supplement 2).

Participant CFI total score LSM difference between atabecestat groups and placebo at month 12 did not show significant group differences; however, nonsignificant subjective worsening from baseline to 12 months was apparent for the 25-mg atabecestat group (eFigure 1A in Supplement 2). There were no treatment group differences for the CFI study partner version (eFigure 1B in the Supplement), participant or study partner versions of the ADCS-ADL-PI, the CDR-SB, or proportion of participants progressing to CDR global score of at least 0.5 (not shown).

Evidence for Recovery After Stopping Treatment

Mean (SD) change in PACC from baseline to last point receiving treatment worsened (−1.23 [1.7]; 95% CI, −1.72 to −0.74), but from last on-treatment to last off-treatment assessment improved by 1.0 point (1.92; 95% CI, 0.47 to 1.54) for the 25-mg atabecestat group (eTable 7 and eFigure 2 in Supplement 2 for linear mixed-effects model results). The RBANS total scale score mean (SD) change from baseline to last on-treatment worsened −1.6 (8.29; 95% CI, −4.01 to 0.8) points, but last on-treatment to last off-treatment scores improved by 1.08 (8.81; 95% CI, −1.45 to 3.61) points for the 25-mg atabecestat group (eTable 7 in Supplement 2).

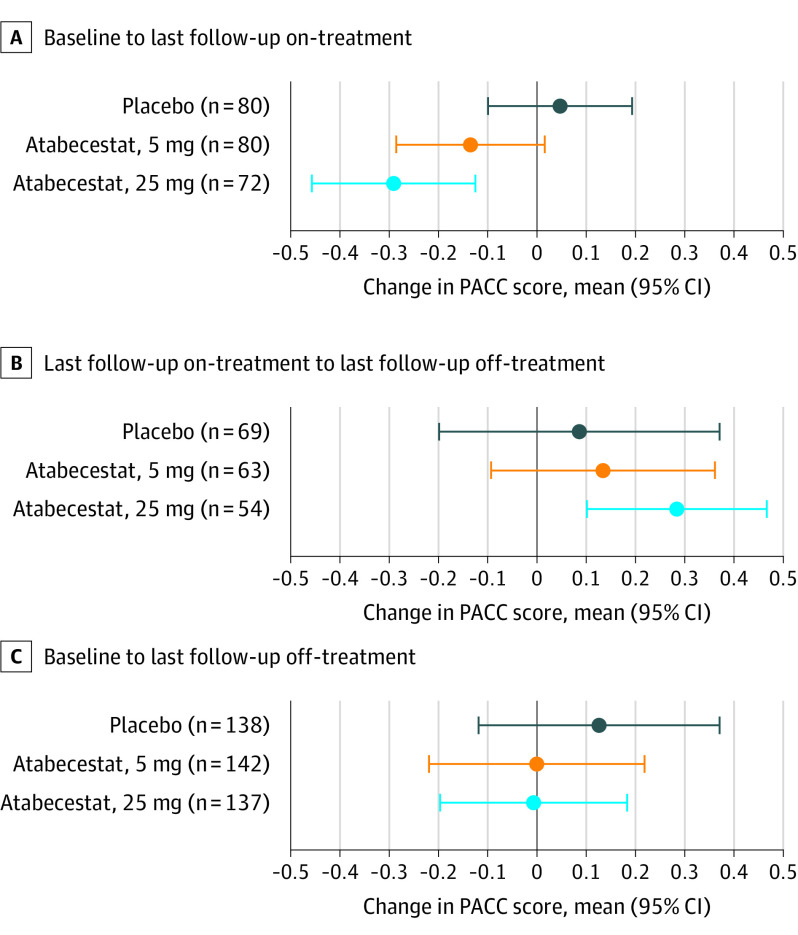

The exposure/observation–adjusted model of PACC change showed atabecestat treatment was associated with cognitive worsening, and cessation of atabecestat was associated with cognitive improvement, both significant in the 25-mg group. Overall baseline to last off-treatment estimated PACC performance returned to baseline level in both atabecestat groups (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Linear Mixed-Effect Model of Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite (PACC) Over Time.

Mean change in PACC during the indicated epoch of follow-up estimated from a mixed-effect model controlling for follow-up prior to discontinuation (median, 4.7 months), follow-up after discontinuation (median, 3.25 months), total exposure (median, 5.3 months), sex, age, and education. In this model, time 0 is defined as the time of last dose. The dependent variable was PACC score at each visit with fixed effects for time (as a continuous variable) before and after last dose in each group, sex, age, education, and total exposure. Random effects were participant and country-specific random intercepts. The covariance structure was assumed to be autoregressive order one and heterogeneous with respect to time.

Safety

No deaths occurred during the study. Serious TEAEs, discontinuations owing to TEAEs, and commonly reported TEAEs were more frequent in atabecestat groups than placebo. Incidence of neuropsychiatric-related AEs, including cognition-related, depression-related, sleep/dream-related, and anxiety-related AEs, were higher in atabecestat groups (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of Treatment-Emergent Serious Adverse Events, Adverse Events (On- and Off-Treatment), and Laboratory Findings (Safety Analysis Set)a.

| On/off-treatment, No./total No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 185) | Atabecestat | ||

| 5 mg (n = 189) | 25 mg (n = 183) | ||

| Serious TEAEs and TEAEs (on treatment) | |||

| Participant, No. (%) | |||

| With ≥1 serious TEAEs | 8 (4.3) | 13 (6.9) | 19 (10.4) |

| With ≥1 TEAEs | 123 (66.5) | 140 (74.1) | 132 (72.1) |

| TEAEs (in >5% of participants and > placebo on-treatment/off-treatment) | |||

| Diarrhea | 7 (3.8)/0 | 12 (6.3)/4(2.2) | 28 (15.3)/2(1.2) |

| Urinary tract infection | 3 (1.6)/4(2.2) | 5 (2.6)/4(2.2) | 11 (6.0)/5(2.9) |

| Cough | 1 (0.5)/1(0.6) | 12 (6.3)/1(0.5) | 4 (2.2)/2(1.2) |

| Abnormal dreams | 1 (0.5)/0 | 4 (2.1)/0 | 11 (6.0)/0 |

| Other TEAEs of interest | |||

| Neuropsychiatric AEs, on-treatment, No. (%) | 5 (2.7) | 16 (8.5) | 30 (16.4) |

| Anxiety-related | 1 (0.5)/0 | 2 (1.1)/1(0.5) | 5 (2.7)/1(0.6) |

| Depression-related | 2 (1.1)/0 | 2 (1.1)/2(1.1) | 6 (3.3)/1(0.6) |

| Sleep dream-relatedb | 2 (1.1)/0 | 13 (6.9)/0 | 18 (9.8)/1(0.6) |

| Cognition-relatedc | 0/0 | 0/1(0.5) | 6 (3.3)/0 |

| Rash-related AEs | 7 (3.8)/1(0.6) | 8 (4.2)/2(1.1) | 13 (7.1)/1(0.6) |

| Treatment emergent high or low laboratory parameters (>5% and >placebo)d | |||

| Greater than ULN | |||

| Alanine aminotransferase | 25/168 (14.9) | 42/174 (24.1) | 58/172 (33.7) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 15/169 (8.9) | 40/176 (22.7) | 45/173 (26.0) |

| Bilirubin | 5/164 (3.0) | 4/172 (2.3) | 9/168 (5.4) |

| γ-Glutamyl transferase | 7/163 (4.3) | 8/169 (4.7) | 15/161 (9.3) |

| Less than LLN | |||

| Phosphate | 3/170 (1.8) | 6/176 (3.4) | 12/171 (7.0) |

| Serum glucose | 12/108 (11.1) | 21/117 (17.9) | 19/100 (19.0) |

| Serum urate, greater than ULN | 6/167 (3.6) | 9/178 (5.1) | 10/167 (6.0) |

| Lymphocytes | 5/166 (3.0) | 6/173 (3.5) | 11/168 (6.5) |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse events; LLN, lower limit of normal; ULN, upper limit of normal; TEAEs, treatment-emergent adverse events.

AEs and serious AEs were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (Med-DRA Version 19.1). Categories are groupings of clinically similar MedDRA preferred terms. On-treatment TEAEs defined as onset while receiving study treatment or within 7 days after the last dose; off-treatment AEs had onset more than 7 days after the last dose.

Insomnia was only sleep/dream-related adverse event reported off treatment.

Amnesia was only cognition-related adverse event reported off treatment.

No. is based on number of participants who were cognitively normal at baseline.

Treatment-emergent increases in ALT and aspartate aminotransferase more than 3 times ULN were seen in 40 participants (11%) receiving atabecestat (13 [6.9%] in the 5-mg group and 27 [14.8%] in the 25-mg group) and in only 1 participant (0.5%) receiving placebo. Except for mild fatigue in 1 participant, these were asymptomatic and resolved spontaneously or after drug discontinuation. One participant (25-mg atabecestat group) met the Hy Law criteria (ie, ALT more than 3 times ULN and total bilirubin more than 2 times ULN). More participants in the atabecestat, 25 mg, group than placebo had treatment-emergent absolute lymphocyte counts that dropped to less than the lower limit of normal (Table 2).

Greater mean decreases in weight at 12 months following baseline were observed in the 25-mg atabecestat group (−1.68 kg) vs the 5-mg group (0.41 kg) and placebo group (0.21 kg); one participant each in the 5-mg and 25-mg groups vs none in the placebo group showed more than 10% weight loss from baseline.

Seven participants experienced new-onset transaminase elevations more than 3 times ULN from 20 to 110 days after stopping atabecestat dosing (vs none after placebo); all eventually returned to normal. Incidence of TEAEs reported after study drug discontinuation were equivalent between participants originally treated with atabecestat and placebo (Table 2).

Exploratory Results

Small dose-related and duration-related decreases from baseline to months 6 and 12 in whole-brain volume were observed in participants taking atabecestat (5 and 25 mg) compared with placebo as measured by vMRI. At months 6 and 12, whole-brain volume decreased in the 25-mg atabecestat group vs placebo (eFigure 3 in Supplement 2). At an individual level, these whole-brain volume decreases did not correlate with change on PACC.

There were no treatment group differences in 12-month change in CSF NfL or total tau. Mean (SD) CSF p181tau in the 5-mg atabecestat group showed a decrease of −2.2 (7.26) pg/mL compared with an increase of 1.8 (5.60) pg/mL with placebo; the 25-mg group also decreased (−2.1 [8.52] pg/mL) (eFigure 4 in Supplement 2). There were no significant correlations between these changes and change in cognition or whole brain volume.

Discussion

The EARLY trial primarily aimed to evaluate efficacy of atabecestat for slowing cognitive decline in preclinical AD. Dosing and enrollment were discontinued prematurely owing to hepatic-related AEs, and participants were followed up off-treatment for up to 6 months. Final analyses of EARLY trial data confirm preliminary results4 showing a small but consistent worsening of cognitive performance as measured by the PACC and RBANS at the first postbaseline assessments (6 and 3 months, respectively), particularly in the high-dose atabecestat group. Other BACEis have had similar findings.5,6 Worsening of cognitive performance was not associated with worsened activities of daily living as assessed by participant or study partner ADCS-ADL-PI, study partner CFI, or clinical status on CDR, suggesting it may have been mild in nature. However, participant-rated CFI results suggested high-dose atabecestat-treated participants may have noted greater subjective cognitive decline. Neuropsychiatric-related and hepatic-related TEAEs did not fully account for the cognitive worsening. Cognitive effects of atabecestat appeared to be primarily associated with episodic memory tasks, such as list learning, story memory, list recognition, story recall, and figure recall. Semantic fluency did not demonstrate the improvement reported with other BACEis.12,13

Hepatic enzyme elevations, diarrhea, rash-related AEs, and neuropsychiatric AEs occurred more frequently with atabecestat than placebo. Some safety findings observed with atabecestat were similar to those observed with other BACEis, including weight loss,5,14 decreased lymphocyte counts,15 diarrhea,14,15 rash,5,16 and sleep-related TEAEs,5,15,16 suggesting a common BACEi mechanism-related etiology.

Consistent with other BACEis, atabecestat was associated with dose-related and duration-related decreases in whole-brain volume compared with placebo treatment.5,14,16 Generally, atabecestat was not associated with consistent effects on CSF biomarkers of tau (p181tau) or neurodegeneration (t-tau and NfL).

The EARLY trial design and amendment permitted follow-up of participants after stopping treatment for up to 6 months. Results suggest recovery of cognition and safety events after stopping atabecestat treatment. The observed recovery of cognitive performance and TEAEs is an important finding for future exploration of BACEi in AD, as is the observation that most AEs reported with BACEi, in this study and others, appear to be dose-related.

Etiology of cognitive worsening and TEAEs related to BACEi is unknown. There are multiple substrates for BACE beyond APP17 that have been associated with alterations in neuronal structure and/or function in animal models, including (1) seizure protein 6,18,19 associated with alterations in neuronal connectivity and long-term potentiation; (2) neuregulin20,21 associated with changes in dendritic spine density and synaptogenesis; and (3) close homologue of L122,23 associated with growth cone collapse. Although it is difficult to compare across trials with different end points and in different populations,5,6 it is notable that the effect sizes of cognitive worsening in preclinical AD may be larger than those observed in patients with symptomatic AD. This observation is supportive of the hypothesis that individuals with more intact synaptic function may be particularly vulnerable to this pattern of treatment-associated transient cognitive worsening.

It is also possible that changes in other APP cleavage fragments (eg, soluble APPβ or C99) associated with BACE inhibition or even changes in Aβ processing could have contributed to cognitive worsening,24,25 in particular given similarities of BACEi findings to adverse effects reported in γ-secretase inhibitor trials.26

There is abundant genetic evidence that overproduction of Aβ42 leads to AD,27 and interference with production of Aβ42 may be protective.28 Decreasing Aβ production remains attractive as a potential disease-modifying strategy for AD. However, for BACEi to be pursued safely researchers will need to explore lower doses with more modest enzyme inhibition, with careful safety/cognitive monitoring.29

Limitations

A major limitation of this study was truncation owing to premature discontinuation of dosing. This resulted in only 37% of 557 participants having a postbaseline PACC and variable exposure time while receiving treatment and observation time after stopping treatment, limiting definitive conclusions. However, worsened cognitive performance, neuropsychiatric adverse events, and reduced whole-brain volume have been observed with several other BACEis,30 increasing the probability that our findings are related to atabecestat and BACE inhibition. The observation that cognitive worsening and neuropsychiatric-related AEs recovered following discontinuation of atabecestat is encouraging but needs replication, given that the observation period after stopping treatment was variable and not preplanned.

Conclusions

Final data from the EARLY trial confirm dose-related worsening of cognition as early as 3 months and presence of neuropsychiatric TEAEs in participants with preclinical AD, with apparent recovery after up to 6 months after stopping treatment. Atabecestat will not be developed further owing to hepatic safety concerns. Given the tremendous potential benefit of an oral antiamyloid agent in the prevention of AD, the findings of this study can be instrumental in better understanding the mechanisms underlying transient cognitive worsening and to explore whether there exists a path forward for low-dose BACE inhibition in the future.

Trial Protocol

eMethods 1. Amyloid Entry Criteria

eMethods 2. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Exclusion Criteria

eMethods 3. Description of Dose Cessation Process and Protocol Continuation Off-treatment(Safety Follow-up Phase)

eTable 1. Characteristics of EARLY Sample: ITT Population, Population with On-Treatment, with Off-Treatment, and with both On- and Off-Treatment PACC Observations.

eTable 2. Demographics and Baseline Characteristics (only participants included in PACC and RBANS on-treatment MMRM analysisa)

eTable 3. Mixed Model Repeated Measurement Analysis of PACC and RBANS Scores: Least Square Mean (±SE) Change from Baseline Relative to Placebo Over Time (ITT Analysis Set)

eTable 4. Sensitivity Analysis for PACC Total Score (On-Treatment, Change from Baseline): Excluding Participants with Neuropsychiatric AEs, Cognition AEs, and Hepatic Enzyme Elevations (Safety Analysis Set)

eTable 5. Mixed Model Repeated Measurement Analysis of Standardized PACC Components (On-Treatment): Least Square Mean (±SE) Change from Baseline Relative to Placebo Over Time (ITT Analysis Set)

eTable 6. Mixed Model Repeated Measurement Analysis of RBANS Subtests (On-Treatment): Least Square Mean (±SE) Change from Baseline Relative to Placebo Over Time (ITT Analysis Set)

eTable 7. Reversibility of Cognitive Worsening Comparison of On-Treatment versus Off-Treatment for PACC and RBANS (Safety Analysis Set)

eFigure 1. Total CFI Score – Cognitive Decline from Baseline to Month 12. A) CFI-Participant Score; B) CFI-Study Partner

eFigure 2. Individual PACC Scores On-Treatment (left of dashed line) and up to 6 Months Off-Treatment (right of dashed line)

eFigure 3. Mean (95% CI) Change from Baseline to Months 6 and 12 in Whole Brain Volume

eFigure 4. Mean (SD) Change from Baseline to Month 12 in CSF NfL, p-Tau181, and t-Tau

eAppendix. List of the EARLY Study Team Investigators

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):280-292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Timmers M, Streffer JR, Russu A, et al. Pharmacodynamics of atabecestat (JNJ-54861911), an oral BACE1 inhibitor in patients with early Alzheimer’s disease: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018;10(1):85. doi: 10.1186/s13195-018-0415-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Novak G, Streffer JR, Timmers M, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of atabecestat (JNJ-54861911), an oral BACE1 inhibitor, in early Alzheimer’s disease spectrum patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study and a two-period extension study. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12(1):58. doi: 10.1186/s13195-020-00614-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henley D, Raghavan N, Sperling R, Aisen P, Raman R, Romano G. Preliminary results of a trial of atabecestat in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(15):1483-1485. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1813435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egan MF, Kost J, Voss T, et al. Randomized trial of verubecestat for prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(15):1408-1420. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imbimbo BP, Watling M. Investigational BACE inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2019;28(11):967-975. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2019.1683160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donohue MC, Sperling RA, Salmon DP, et al. ; Australian Imaging, Biomarkers, and Lifestyle Flagship Study of Ageing; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative; Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study . The preclinical Alzheimer cognitive composite: measuring amyloid-related decline. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(8):961-970. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mormino EC, Papp KV, Rentz DM, et al. Early and late change on the preclinical Alzheimer’s cognitive composite in clinically normal older individuals with elevated amyloid β. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(9):1004-1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.01.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dmitrienko A, Tamhane AC, Wiens BL. General multistage gatekeeping procedures. Biom J. 2008;50(5):667-677. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200710464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walsh SP, Raman R, Jones KB, Aisen PS; Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Group . ADCS prevention instrument project: the Mail-In Cognitive Function Screening Instrument (MCFSI). Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20(4)(suppl 3):S170-S178. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213879.55547.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Randolph C. Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS). San Antonio, TX; The Psychological Corporation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stern RA, Wessels AM, Selzler KJ, Andersen SW, Mullen J, Sims JR. Performance on exploratory efficacy variables in Amaranth, a randomized phase 2/3 study in early Alzheimer’s disease with lanabecestat. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(7):873. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2019.06.4620 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egan MF, Kost J, Lines C, et al. FTS3-01-05: Further analyses of cognitive outcomes in the APECS phase-3 trial of verubecestat in prodromal AD. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(7):874. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2019.06.4622 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wessels AM, Tariot PN, Zimmer JA, et al. Efficacy and safety of lanabecestat for treatment of early and mild Alzheimer disease: the AMARANTH and DAYBREAK-ALZ randomized clinical trials. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(2):199-209. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.3988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lynch SY, Kaplow J, Zhao J, Dhadda S, Luthman J, Albala B. Elenbecestat, E2609, a BACE inhibitor: results from a phase 2 study in subjects with mild cognitive impairment and mild-to-moderate dementia due to Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(7):1623. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.07.21330055132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egan MF, Kost J, Tariot PN, et al. randomized trial of verubecestat for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(18):1691-1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barão S, Moechars D, Lichtenthaler SF, De Strooper B. BACE1 physiological functions may limit its use as therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 2016;39(3):158-169. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2016.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pigoni M, Wanngren J, Kuhn PH, et al. Seizure protein 6 and its homolog seizure 6-like protein are physiological substrates of BACE1 in neurons. Mol Neurodegener. 2016;11(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s13024-016-0134-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu K, Xiang X, Filser S, et al. Beta-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1 inhibition impairs synaptic plasticity via seizure protein 6. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;83(5):428-437. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Müller T, Braud S, Jüttner R, et al. Neuregulin 3 promotes excitatory synapse formation on hippocampal interneurons. EMBO J. 2018;37(17):e98858. doi: 10.15252/embj.201798858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang YN, Figueiredo D, Sun XD, et al. Controlling of glutamate release by neuregulin3 via inhibiting the assembly of the SNARE complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(10):2508-2513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1716322115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barão S, Gärtner A, Leyva-Díaz E, et al. Antagonistic effects of BACE1 and APH1B-γ-secretase control axonal guidance by regulating growth cone collapse. Cell Rep. 2015;12(9):1367-1376. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.07.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hitt B, Riordan SM, Kukreja L, Eimer WA, Rajapaksha TW, Vassar R. β-Site amyloid precursor protein (APP)-cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1)-deficient mice exhibit a close homolog of L1 (CHL1) loss-of-function phenotype involving axon guidance defects. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(46):38408-38425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.415505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chasseigneaux S, Allinquant B. Functions of Aβ, sAPPα and sAPPβ : similarities and differences. J Neurochem. 2012;120(suppl 1):99-108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07584.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freude KK, Penjwini M, Davis JL, LaFerla FM, Blurton-Jones M. Soluble amyloid precursor protein induces rapid neural differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(27):24264-24274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.227421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henley DB, Sundell KL, Sethuraman G, Dowsett SA, May PC. Safety profile of semagacestat, a gamma-secretase inhibitor: IDENTITY trial findings. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(10):2021-2032. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2014.939167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bateman RJ, Aisen PS, De Strooper B, et al. Autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease: a review and proposal for the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2011;3(1):1. doi: 10.1186/alzrt59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jonsson T, Atwal JK, Steinberg S, et al. A mutation in APP protects against Alzheimer’s disease and age-related cognitive decline. Nature. 2012;488(7409):96-99. doi: 10.1038/nature11283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Satir TM, Agholme L, Karlsson A, et al. Partial reduction of amyloid β production by β-secretase inhibitors does not decrease synaptic transmission. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12(1):63. doi: 10.1186/s13195-020-00635-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Picking Through the Rubble, Field Tries to Salvage BACE Inhibitors. Alzforum. Accessed September 25, 2020. https://www.alzforum.org/news/conference-coverage/picking-through-rubble-field-tries-salvage-bace-inhibitors

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eMethods 1. Amyloid Entry Criteria

eMethods 2. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Exclusion Criteria

eMethods 3. Description of Dose Cessation Process and Protocol Continuation Off-treatment(Safety Follow-up Phase)

eTable 1. Characteristics of EARLY Sample: ITT Population, Population with On-Treatment, with Off-Treatment, and with both On- and Off-Treatment PACC Observations.

eTable 2. Demographics and Baseline Characteristics (only participants included in PACC and RBANS on-treatment MMRM analysisa)

eTable 3. Mixed Model Repeated Measurement Analysis of PACC and RBANS Scores: Least Square Mean (±SE) Change from Baseline Relative to Placebo Over Time (ITT Analysis Set)

eTable 4. Sensitivity Analysis for PACC Total Score (On-Treatment, Change from Baseline): Excluding Participants with Neuropsychiatric AEs, Cognition AEs, and Hepatic Enzyme Elevations (Safety Analysis Set)

eTable 5. Mixed Model Repeated Measurement Analysis of Standardized PACC Components (On-Treatment): Least Square Mean (±SE) Change from Baseline Relative to Placebo Over Time (ITT Analysis Set)

eTable 6. Mixed Model Repeated Measurement Analysis of RBANS Subtests (On-Treatment): Least Square Mean (±SE) Change from Baseline Relative to Placebo Over Time (ITT Analysis Set)

eTable 7. Reversibility of Cognitive Worsening Comparison of On-Treatment versus Off-Treatment for PACC and RBANS (Safety Analysis Set)

eFigure 1. Total CFI Score – Cognitive Decline from Baseline to Month 12. A) CFI-Participant Score; B) CFI-Study Partner

eFigure 2. Individual PACC Scores On-Treatment (left of dashed line) and up to 6 Months Off-Treatment (right of dashed line)

eFigure 3. Mean (95% CI) Change from Baseline to Months 6 and 12 in Whole Brain Volume

eFigure 4. Mean (SD) Change from Baseline to Month 12 in CSF NfL, p-Tau181, and t-Tau

eAppendix. List of the EARLY Study Team Investigators

Data Sharing Statement