Abstract

This study investigated whether the effect of exposure to code-switching on bilingual children’s language performance varied depending on verbal working memory. A large sample of school-aged Spanish-English bilingual children (N = 174, Mage = 7.78) was recruited, and children were administered language measures in English and Spanish. The frequency with which the children were exposed to code-switching was gathered through parent report. For children with high verbal working memory, greater exposure to code-switching was associated with higher levels of language ability. In contrast, for children with lower verbal working memory, greater exposure to code-switching was associated with lower levels of language ability. These findings indicate that children’s cognitive processing capacity dictates whether exposure to code-switching facilitates or hinders language skills.

Keywords: code-switching, language ability, verbal working memory, bilingualism

Code-switching (alternation between languages) is a common practice among bilinguals. Yet, a robust psycholinguistic literature indicates that code-switching carries processing costs, both in production (Bobb & Wodniecka, 2013; Fricke, Kroll, & Dussias, 2016; Meuter & Allport, 1999) and in comprehension (Altarriba, Kroll, Sholl, & Rayner, 1996; Byers-Heinlein, Morin-Lessard, & Lew-Williams, 2017; Bultena, Dijkstra, & Van Hell, 2015a; b; Proverbio, Leoni, & Zani, 2004). Why then do bilinguals code-switch? Being able to code-switch enables bilinguals to precisely express the intended meanings and to circumvent lexical gaps (Green & Wei, 2014). At the same time, bilinguals appear to be able to capitalize on subtle speech cues to offset the comprehension costs associated with an upcoming code-switch (Fricke, Kroll, & Dussias, 2016). Thus, generally, the advantages associated with being able to switch between languages outweigh the (possible) processing costs associated with a language switch. Perhaps this is why code-switching is rather common in the speech of bilingual parents, although the degree of mixed-language input in a bilingual child’s environment varies widely both within and across bilingual communities (e.g., Bail, Morini, & Newman, 2015; Bentahila & Davies, 1995; Byers-Heinlein, 2013; Nicoladis & Secco, 2000; Tare & Gelman, 2011). The question then is: does exposure to code-switching contribute to individual differences in bilingual children’s language abilities, akin to other qualitative aspects of language input?

Only a few previous studies have examined the relation between exposure to code-switching and bilingual children’s language performance, and the findings paint a rather confusing picture. In two studies, Place and Hoff (2011; 2016) found that exposure to mixed-language input was not associated with language outcomes in 25-to-30 month-old Spanish-English bilingual children. In both studies, children’s language exposure was measured via a language diary technique, with parents noting their language use in 30-minute increments. Parental language mixing was defined as the proportion of waking time during which the child was exposed to two languages within the same 30-minute block. Notably, this measure of dual-language input does not distinguish between code-switching and sequential use of the two languages within the same block of time. Place and Hoff (2011) found no relation between this measure of mixed-language input and children’s productive vocabulary and grammar, measured via a parent report. In a follow-up study, Place and Hoff (2016) replicated this null finding, extending it to measures of auditory comprehension and expressive vocabulary skills measured via standardized tests.

In contrast, a few studies revealed relations between bilingual children’s exposure to code-switched input and language outcomes, albeit with opposite results. Byers-Heinlein (2013) examined the relation between a parental-report measure of intra-sentential code-mixing (using words from two languages within the same sentence) and 18–24-month-old bilingual children’s performance on English receptive and productive vocabulary measures, also indexed via a parent report. The findings suggested that increased frequency of parental language mixing was associated with reduced receptive and productive vocabulary in the children, over and above the effects of English exposure, gender, age, and linguistic balance. Similarly, Lipsky (2013) found that the amount of code-switching by the teacher during storybook reading (quantified as the number of Spanish words used by the teacher during an English reading session) was negatively related to children’s English receptive vocabulary outcomes, measured via a standardized test. The children in the Lipsky (2013) study were 36–59-month-old Head Start students. In contrast, Bail, Morini, and Newman (2015) found the opposite pattern, showing that intra-sentential code-switching was positively related to 18–24-month-old bilingual children’s vocabulary size. Unlike Byers-Heinlein (2014), Bail et al. (2015) derived an objective measure of code-switching, which they obtained from a parent-child interaction sample; their measure of productive vocabulary size was the same parent-report measure used by Byers-Heinlein (2013). How then to reconcile the rather conflicting findings across these studies?

Beyond considering the obvious methodological culprits (the distinct approaches to measuring mixed-language input and the different indexes of language ability used in these studies), there is a theoretically grounded possibility related to individual differences in children’s ability to process code-switched input. Verbal working memory is a capacity-constrained system with well-documented individual differences in the population (Pickering & Gathercole, 2001). A classic theory of language comprehension anchors individual differences in language comprehension ability to individual differences in working memory capacity (Daneman & Carpenter, 1980; Daneman and Merikle, 1996), with extensive empirical evidence supporting a strong relation between comprehension and WM measures such as the backward digit-span, in bilingual (e.g., Buac, Gross, & Kaushanskaya, 2016; Cockroft, 2016; Engel de Abreau et al., 2011; Kormos & Safar, 2008) but also in monolingual (e.g., Cain, Oakhill, & Bryant, 2004; Chrysochoou, Bablekou, Masoura, & Tsigilis, 2013; Leather & Henry; 1994; Seigneuric & Ehrlich, 2005; Verhagen & Leseman, 2016) children. Daneman and Carpenter (1980) argued that weaknesses in WM would lead to deficits in comprehension, particularly for the more demanding comprehension tasks that require integration of words, phrases, and sentences into a coherent whole. Processing of code-switched input may constitute just such a task, with a language switch posing processing and integration costs (Altarriba, Kroll, Sholl, & Rayner, 1996; Bultena, Dijkstra, & Van Hell, 2015a; b; Proverbio, Leoni, & Zani, 2004), and inducing an increased cognitive load (Byers-Heinlein, Morin-Lessard, & Lew-Williams, 2017). In fact, neuroimaging literature has revealed that code-switches encountered during comprehension tasks elicit responses that suggest an increased effort in memory updating processes (e.g., Moreno, Federmeier, & Kutas, 2002; van Der Meijet al., 2011). Thus, the hypothesis we tested in the present study was that children with different levels of verbal working memory capacity may respond to code-switched input in distinct ways.

Specifically, we hypothesized that children with lower levels of verbal working memory capacity would find code-switched input challenging, and thus we predicted a negative association between increased amounts of code-switched input and language skills for children with lower levels of verbal working memory. We predicted that children with higher levels of working memory capacity would find it easier to process code-switched input, and that thus code-switched input may not affect or may even facilitate their language skills. There is a number of reasons why children’s language skills might benefit from code-switched input. For instance, code-switched input may highlight translation equivalents (Bail et al., 2015) thus facilitating vocabulary acquisition across both languages. It may also draw children’s attention to the pragmatic situations within which language input unfolds (Yow & Markman, 2016), thus enhancing the child’s ability to acquire linguistic information from a communicative exchange. These possibilities are entirely speculative, and our goal was not to adjudicate between them. Rather, we aimed to examine whether in principle it is possible for code-switched input to be associated with positive language outcomes in some bilingual children.

Our hypothesis regarding the moderating effects of verbal working memory on the relation between exposure to code-switching and language outcomes is conceptually similar to the classic threshold hypothesis of bilingual language development (e.g., Cummins, 1976; 1979; 1984; 2000). While the focus of the threshold hypothesis was transfer of linguistic knowledge between a bilingual’s two languages, with the degree of transfer hypothesized to depend on whether bilinguals attained threshold levels of language proficiency in their two languages, it has also been used to explain how fluctuations in bilinguals’ language proficiency influence performance on language-specific (e.g., Cha & Goldenberg, 2015) and cognitive measures (e.g., Ricciardelli, 1992). Here, we hypothesized that threshold levels of verbal working memory capacity may be necessary in order to observe beneficial effects of code-switched input on bilingual children’s language outcomes. We tested this hypothesis in a large sample of school-aged Spanish-English bilingual children. The advantage to testing children in the school-aged range (vs. infants or very young children) is that it enabled us to administer comprehensive standardized measures of language ability to the children in both the receptive and the expressive domains, in both languages.

Method

Participants

One hundred seventy-four typically developing Spanish-English bilingual children (88 boys) between the ages of 5 – 11 years old were recruited. All children passed a bilateral pure tone hearing screening at 20 dB at 1000 Hz, 2000 Hz, and 4000 Hz. The children were all exposed to English and Spanish at the time of the study. In general, the children in the study fell into one of three groups: 43% (n = 75) were exposed to English and Spanish before their third birthday; 20 % (n = 35) were native Spanish speakers who acquired English upon entry into formal schooling; and 37 % (n = 64) were native English speakers who acquired Spanish via dual-immersion programs where 50–90% of their school instruction was in Spanish.

Participants with a history of developmental language delay, participants who were receiving language therapy services, and children with an organic medical diagnosis were excluded. Information about primary caregivers’ language use, language proficiency, and socioeconomic status (operationalized as maternal years of education) was collected through parent interviews. Information about children’s current language exposure, language dominance, and language preference was collected through parent questionnaires and a face-to-face parent interview. In addition, parents completed the Language Experience and Proficiency Questionnaire (LEAP-Q, Marian, Blumenfeld, & Kaushanskaya, 2007) about their own language background and educational history. See Table 1 for participant characteristics across all the children tested. See Supplementary Materials (Table S1) for participant characteristics in each of the three sub-groups of the children.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics, Means (SDs)

| N = 174 | |

|---|---|

| Gender | 88 boys; 86 girls |

| Age | 7.78 (1.55) |

| Maternal Years of Educationa | 15.04 (4.10) |

| IQb | 106.80 (14.88) |

| Age at first exposure to English (months) | 10.74 (19.75) |

| Age at first exposure to Spanish (months) | 24.16 (29.29) |

| Current English Exposurec (%) | 59 (20) |

| Exposure to Code-Switchingd | 2.86 (1.68) |

| English Core Languagee | 96.63 (18.82) |

| English Receptive Languagee | 102.6 (14.56) |

| English Expressive Languagee | 95.76 (19.07) |

| Spanish Core Languagef | 86.67 (15.38) |

| Spanish Receptive Languagef | 99.03 (13.22) |

| Spanish Expressive Languagef | 83.01 (15.87) |

| Verbal Working Memoryg | 102.28 (16.25) |

| Language heard at school | |

| English only | 44 |

| Spanish at least 50% of time | 130 |

| Language heard at home | |

| Mostly English | 91 |

| Mostly Spanish | 62 |

| Both English and Spanish | 21 |

| Language spoken at home | |

| Mostly English | 101 |

| Mostly Spanish | 49 |

| Both English and Spanish | 24 |

| Parent Language Proficiencyh | |

| English | |

| Speaking | 8.1 (2.44) |

| Understanding | 8.53 (2.16) |

| Reading | 8.34 (2.48) |

| Spanish | |

| Speaking | 6.92 (3.42) |

| Understanding | 7.45 (2.99) |

| Reading | 7.03 (3.14) |

Used as proxy for Socio Economic Status

Standard Score; Matrices subtest of Kaufmann Brief Intelligence Test-II

Parental report of exposure to language during waking hours in a typical week

Parental report of average exposure to code-switching that the child experienced in their day-to-day environment on a frequency scale from 0–10

Standard score; Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-4

Standard score; Spanish Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-4

Standard score; Numbers reversed subtest from the Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Cognitive Abilities

Parent Spanish and English self-reported proficiency (0-to-10 scale)

Procedure

Participants were tested individually in a quiet room at the Waisman Center. The children completed standardized assessments of language and cognition over the course of 3 sessions, while the parents were interviewed. The interviews with the parents were conducted either in English or in Spanish, depending on the parent’s proficiency and preference.

Exposure to Code-Switching

The parents were interviewed face-to-face about their child’s language environment. For the purposes of the present study, responses to one question in particular were used to calculate the amount of exposure to code-switching that each child experienced on a daily basis. We first provided the parents with our definition of code-switching: “Code-switching is a communication strategy that some bilinguals use, where they switch back and forth between languages during conversations with others who speak their two languages. Sometimes they switch languages from one sentence to the next during the conversation, and sometimes they switch languages within a single sentence. Code-switches within a sentence may be a single word or a larger group of words. Some bilinguals code-switch regularly, while others code-switch rarely, if at all.” Thus, our definition of code-switching encompassed inter- and intra-sentential code-switching, as well as single-word borrowing.

Parents were provided with a list of individuals that the child could interact with, including the child’s mother, father, siblings, grandparents, other relatives, friends during play, classmates at school, adults at school, and strangers. The parents were then asked: “If this individual/these individuals speak both Spanish and English, how often do they code-switch around your child?” The parents were provided with a frequency scale, where zero stood for “never”, five stood for “half the time”, and ten stood for “always.” Ratings were averaged across all persons to create a measure of average exposure to code-switching that the child experienced in their environment.

Standardized Measures

The Visual Matrices subtest of the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test (KBIT-2, Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004) was used to assess children’s non-verbal intelligence. Items on the subtest require understanding of spatial relations, use of abstract reasoning and of problem-solving strategies. All children scored within the typical range on this measure (see Table 1).

The Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-Fourth Edition (CELF-4, Semel, Wiig, & Secord, 2003) was used to evaluate children’s expressive and receptive language abilities in English. The Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-Fourth Spanish Edition (CELF-4 Spanish, Wiig, Secord, & Semel, 2006) was used to evaluate children’s expressive and receptive language abilities in Spanish. The following CELF-4 performance indexes served as dependent variables: Core Language, Receptive Language, and Expressive Language. This was done in order to examine whether exposure to code-switching affects the different modalities of language use (receptive vs. expressive) to different degrees. Standard scores were used as performance measures for all these indices.

Core Language is a measure of general language ability that reflects a child’s overall language performance across both receptive and expressive modalities, and lexical-semantic and syntactic domains. The Receptive Language index is a measure of auditory comprehension, while the Expressive Language index is a measure of expressive language skills. Generally, reliability and validity checks for the CELF-4 composite scores have revealed adequate reliability and validity.

Verbal Working Memory

Verbal working memory was assessed via the Numbers Reversed subtest from the Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Cognitive Abilities (WJ III COG; Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001). The children repeated numbers backward in ever increasing sequences. This measure was administered in English to all children. Standard scores were used in all the analyses.

Analyses

All de-identified data and scripts have been uploaded into Open Science Framework (https://doi.org/10.3886/E107441V1). Separate regression models were constructed using R Studio Version 1.0.153 for each CELF-4 index. Regression tables were constructed using the package stargazer (Hlavac, 2018). We regressed each CELF-4 index (Core, Receptive, and Expressive) on verbal working memory (mean centered), exposure to code-switching (mean centered), and the interaction between them. Therefore, the coefficients of these centered variables represent the effect of that variable at the average value of the other variables in the model. Because SES (r =.54), current exposure to English (r =.52), and age of English acquisition (r = −.37) were correlated with CELF-4 Core Language index scores (see Table S2 in Supplementary Materials for the full correlation matrix), they were entered as covariates in all models. That is, our analyses examined the effects of exposure to code-switching on language performance over and above the effects of SES, language exposure, and age of acquisition. To account for possible multicollinearity among related predictor variables, Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) were computed for each regression model. Results indicated a very low level of multicollinearity among variables (VIFs for English language measures as the outcome variable ranged from 1.17 to 1.49, and VIFs for Spanish language measures as the outcome variable ranged from 1.14 to 1.68).

Results

English language measures

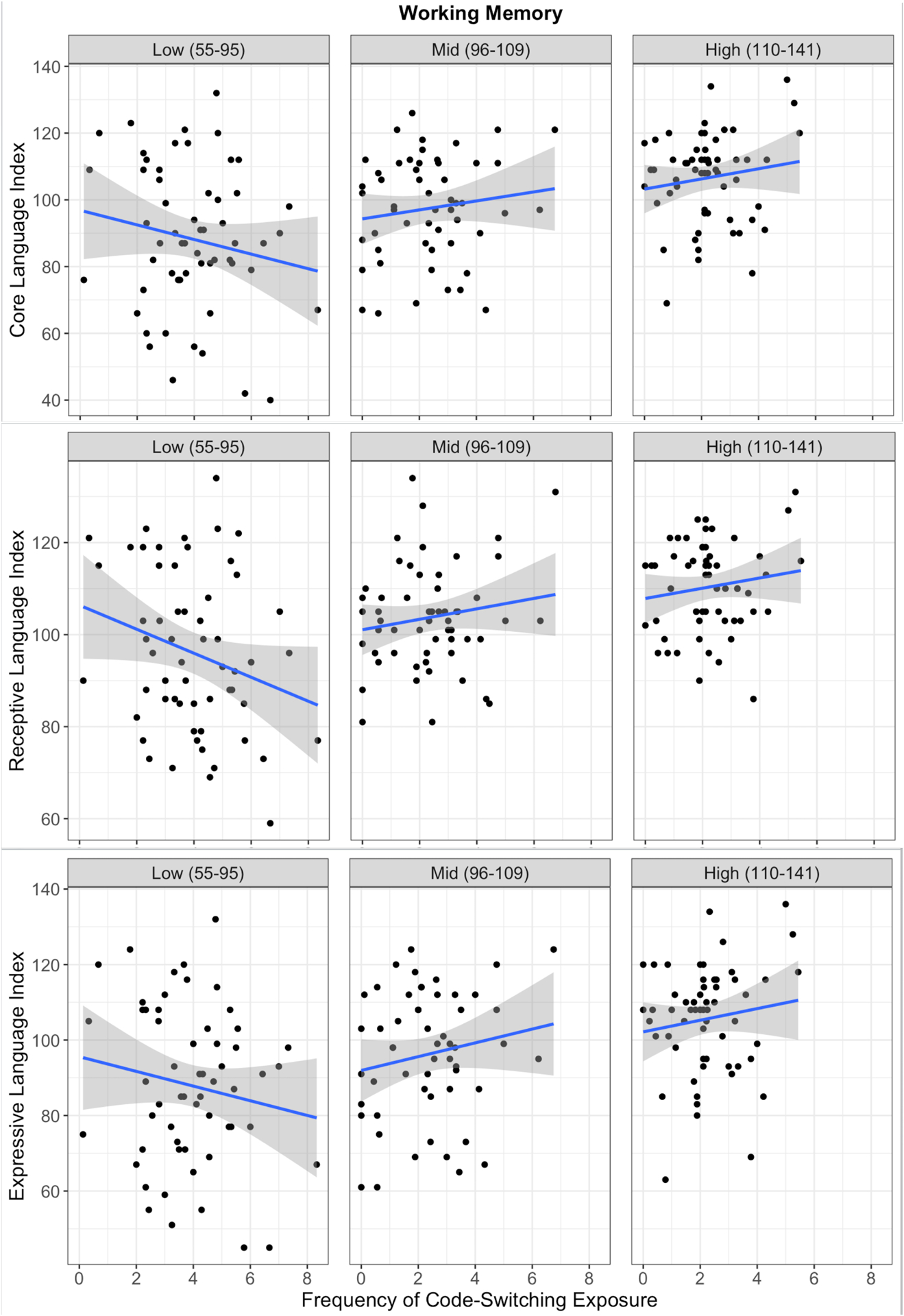

Across all three indexes of English language performance, a significant interaction was observed between verbal MW and exposure to code-switching. For the receptive language index, this interaction remains significant when the covariates are not included in the model. However, it is rendered non-significant for the other dependent variables when the covariates are excluded from the models. In children with weaker working memory skills, greater exposure to code-switching was associated with lower language scores. In contrast, in children with stronger working memory skills, greater exposure to code-switching was associated with higher language scores. The full models for each of the three English performance indexes can be found in Table 2. A graphical representation of the interaction between verbal WM and exposure to code-switching for the three indices can be found in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Regression Models for English CELF-4 Indices, B(SE)

| Dependent variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Language | Receptive Language | Expressive Language | |

| Intercept | 66.37*** (4.88) | 87.15*** (3.99) | 63.35*** (4.91) |

| SESa | 1.20*** (0.29) | 0.99*** (0.24) | 1.28*** (0.29) |

| Current Exposure to Englishb | 26.47*** (6.33) | 6.95 (5.23) | 28.09*** (6.37) |

| AoA Englishc | −0.16** (0.06) | −0.16** (0.05) | −0.16** (0.06) |

| Working Memoryd | 6.54*** (1.14) | 4.77*** (0.95) | 6.19*** (1.15) |

| Exposure to CSe | 2.10† (1.15) | 1.08 (0.94) | 2.63* (1.16) |

| WM:CSf | 2.54* (1.04) | 2.79** (0.86) | 2.58* (1.05) |

| ηp² WM:CSg | 0.035 | 0.059 | 0.036 |

| Observations | 169 | 173 | 169 |

| R2 | 0.52 | 0.44 | 0.52 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.50 | 0.42 | 0.50 |

| F Statistic | 28.87*** | 21.73*** | 29.20*** |

| (df = 6; 162) | (df = 6; 166) | (df = 6; 162) | |

Note:

p < 0.10,

p <0.05;

p <0.01;

p <0.001

Socio Economic Status measured by maternal years of education

Parental report of percent exposure to English during waking hours in a typical week

Parental report of first exposure to English

Woodcock-Johnson III Number Reversed scores

Amount of code-switching heard on a 0–10 scale, averaged across family and school persons

Interaction between working memory and exposure to code-switching

Effect size of interaction; partial eta squared

Figure 1.

Interaction between working memory and exposure to code-switching for CELF-4 English Indices. Raw data are presented. Although verbal working memory was measured as a continuous variable in all models, the graphs were created by splitting verbal working memory abilities by thirds.

Additional findings of note were the following: Across all three analyses, a main effect of verbal working memory was observed, such that higher verbal working memory scores were associated with stronger language performance. The main effect of exposure to code-switching was significant for Expressive Language (F(1, 162) = 6.05, p < .05), with greater exposure to code-switching associated with higher expressive language scores. The main effect of exposure to code-switching was not statistically significant for Receptive Language (F(1, 166) = 1.32 , p > .05), and was only marginally significant for Core Language (F(1, 162) = 3.36, p = .07).

Spanish Language Measures

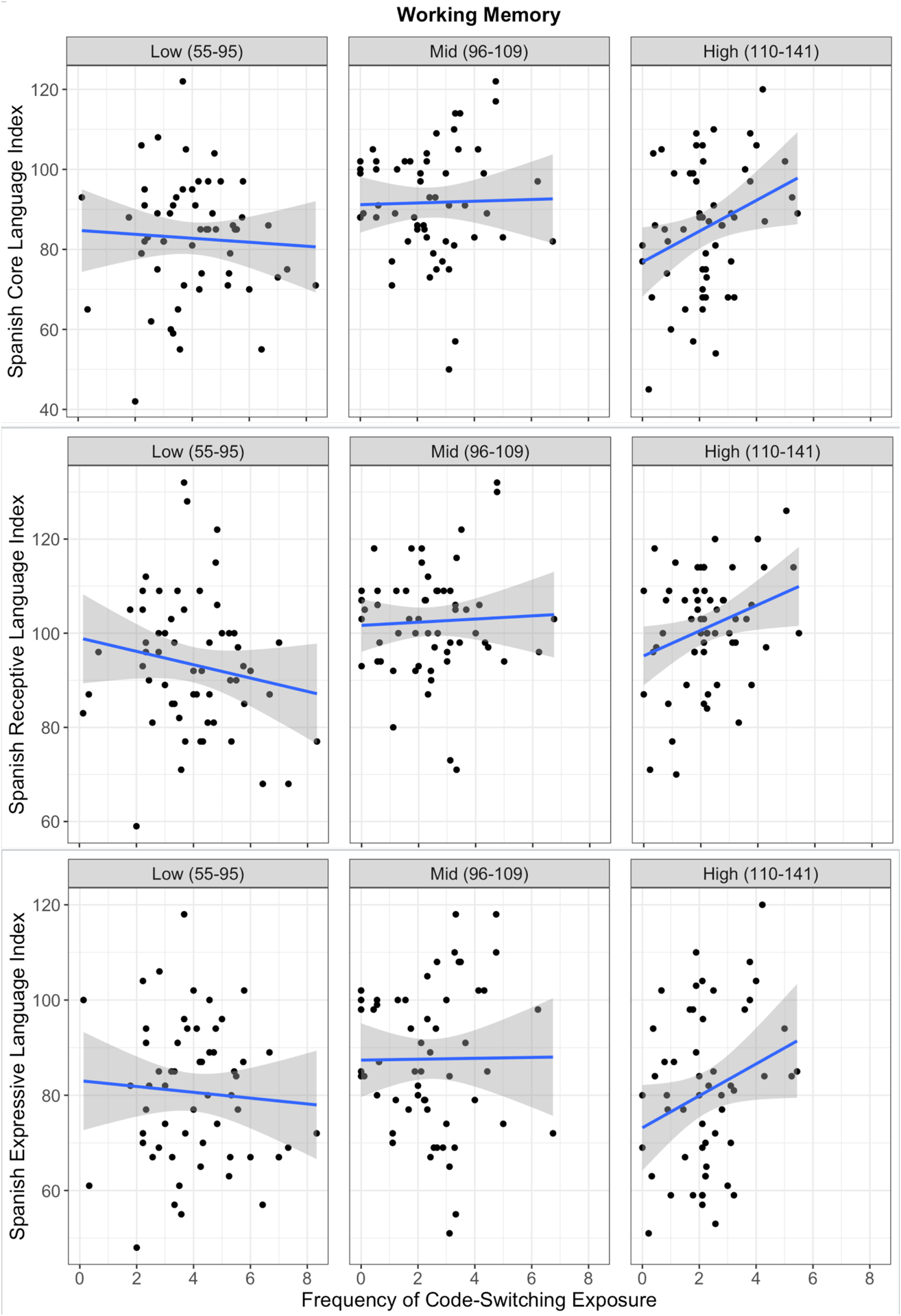

The findings for Spanish language measures patterned similarly to the findings for English language measures. Across all three indexes of Spanish language performance, a significant interaction was observed between verbal MW and exposure to code-switching. For the receptive language index, this interaction remains significant when the covariates are not included in the model. However, it is rendered non-significant for the other dependent variables when the covariates are excluded from the models. In children with weaker working memory skills, greater exposure to code-switching was associated with lower language scores. In contrast, in children with stronger working memory skills, greater exposure to code-switching was associated with higher language scores. The full models for each of the three Spanish performance indexes can be found in Table 3. A graphical representation of the interaction between verbal WM and exposure to code-switching for the three indices can be found in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Regression Models for Spanish CELF-4 Indices, B(SE)

| Dependent variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Language | Receptive Language | Expressive Language | |

| Intercept | 67.83*** (6.25) | 89.85*** (5.53) | 64.55*** (6.10) |

| SESa | 0.35 (0.31) | 0.37** (0.27) | 0.25 (0.31) |

| Current Exposure to Spanishb | 37.37*** (6.75) | 11.37** (6.10) | 42.07*** (6.60) |

| AoA Spanishc | −0.04 (0.05) | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.04) |

| Working Memoryd | 2.89* (1.14) | 4.53*** (1.04) | 1.64 (1.12) |

| Exposure to CSe | 0.67 (1.16) | 0.64 (1.04) | 0.09 (1.13) |

| WM:CSf | 2.18* (1.03) | 1.95* (0.94) | 2.26** (1.01) |

| ηp² WM:CSg | 0.027 | 0.025 | 0.031 |

| Observations | 166 | 174 | 166 |

| R2 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.35 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.33 |

| F Statistic | 10.30*** | 6.18*** | 14.54*** |

| (df = 6;159) | (df = 6; 167) | (df = 6;159) | |

Note:

p <0.05;

p <0.01;

p <0.001

Socio Economic Status measured by maternal years of education

Parental report of percent exposure to Spanish during waking hours in a typical week

Parental report of first exposure to Spanish

Woodcock-Johnson III Number Reversed scores

Amount of code-switching heard on a 0–10 scale, averaged across family and school persons

Interaction between working memory and exposure to code-switching

Effect size of interaction; partial eta squared

Figure 2.

Interaction between working memory and exposure to code-switching for CELF-4 Spanish Indices. Raw data are presented. Although verbal working memory was measured as a continuous variable in all models, the graphs were created by splitting verbal working memory abilities by thirds.

Additional findings of note were the following: Verbal WM was significantly associated with performance on the Spanish Core (F(1, 159) = 6.37, p < .05) and Receptive Language (F(1, 167) = 19.03, p < .001) Indexes. However, it was not associated with performance on the Expressive Language Index (F(1, 159) = 2.14, p > .05). Furthermore, across all three models, there was no main effect of exposure to code-switching.

Discussion

Does exposure to code-switching carry consequences for bilingual children’s language development? The findings from the current study suggest that it may depend on the children’s verbal working memory capacity. For children with lower levels of verbal working memory, code-switched input appears to carry risks, with increased exposure to code-switching associated with reduced language scores. In contrast, for children with higher levels of verbal working memory, code-switched input does not appear to carry risks, with increased exposure to code-switching associated with improved language scores. Notably, these findings hold for both of the bilinguals’ languages, and for both expressive and receptive language skills.

Our results provide a possible reconciliation for the discrepant findings in the literature, with some studies indicating null associations between exposure to mixed-language input and language (Place & Hoff, 2011; 2014), some studies indicating negative effects of exposure to mixed-language input on language (Byers-Heinlein, 2013; Lipsky, 2013), and one study suggesting a positive effect of exposure to mixed-language input on language (Bail, Morini, & Newman, 2015). Our findings also speak to the broader psycholinguistic literature on language switching, where a small number of studies has failed to demonstrate processing costs associated with comprehending mixed-language input (Gullifer, Kroll, & Dussias, 2013; Kohnert & Bates, 2002), challenging the larger literature indicating that comprehension of code-switched input is more effortful than comprehension of single-language input (Altarriba, et al., 1996; Bultena, et al., 2015a; b; Proverbio et al., 2004). It is possible that at least some of the discrepancies across studies may be the result of fluctuations in participants’ verbal working memory skills.

Why may children with different levels of verbal working memory respond differently to code-switched input? At the very least, code-switched input is more variable than single-language input, and it may be more challenging. The basic ability to process such input therefore should logically underpin the ability to acquire information from it. Individual differences in verbal working memory have been tightly linked with variability in children’s language outcomes (e.g., Cain, Oakhill, & Bryant, 2004; Engel de Abreu & Gathercole, 2012; Kormos & Sáfár, 2008; Verhagen & Leseman, 2016). Therefore, a certain threshold level of verbal working memory capacity may be necessary in order to efficiently process linguistic information embedded in code-switched input. However, the correlational nature of the data preclude a causal interpretation of the relation among the variables under study. In fact, it is possible that verbal working memory and exposure to code-switching (for instance) enjoy a bi-directional connection, where increased verbal working memory capacity is associated with enhanced ability to process code-switching input, and in turn, code-switched input may boost the development of the verbal working memory system as it works to accommodate to such input. In interpreting the findings, it is important to acknowledge that while the statistical effect of the interaction between verbal WM capacity and exposure to code-switching was indeed significant, it was quite small. It is also important to acknowledge that while we statistically controlled for the effects of maternal years of education, language exposure, and age of acquisition in the analyses, this may not have accounted for the effects of SES or the effects of language proficiency and balance fully. Finally, we do not envision verbal working memory to be the only moderator of the relation between exposure to code-switching and language outcomes in bilingual children. A range of cognitive skills (including inhibitory control and phonological short-term memory), a range of linguistic skills (e.g., degree of balance between the two languages; robustness of the linguistic skills in the two languages; etc.), and a range of experiences (e.g., extent to which code-switching is practiced in the community; extent to which the child engages in code-switching; etc.) may contribute to the strength and the direction of an association between exposure to code-switched input and language skills.

What are the implications of our findings? For researchers working in the area of bilingual language development, our findings indicate that fluctuations in bilingual children’s language-specific abilities are related not only to absolute levels of exposure to their two languages but also to the type of exposure. This notion is not a new one. Hoff and colleagues (Place & Hoff, 2011; 2016) have shown that quality of bilingual language input contributes to bilingual children’s language outcomes over and above exposure levels. In their studies, they hypothesized that mixed-language input might function similarly to non-native input, with both types of input characterized as lower quality input (compared to single-language and native language input). What they found instead was a lack of an association between their measure of mixed-language input and children’s language performance. Our results indicate that mixed-language input may in fact serve as high-quality input, but only for a subset of children capable of processing such input.

One important consideration for future work is the possibility that different types of code-switching behaviors in children’s language environment may carry distinct consequences for bilingual children’s language development. That is, switches within a single sentence, including single-word borrowings, may induce different processing strategies than switches across sentences (e.g., Byers-Heinlein, Morin-Lessard, & Lew-Williams, 2017). In our study, we collapsed across all types of code-switching behaviors, and thus obtained a rather global measure of exposure to code-switched input. Future studies may consider disentangling different types of code-switching behaviors, and it will be important to examine the reliability with which parents can report on the different types of code-switching behaviors.

In general, whether parents are reliable in their reports of code-switching behaviors is an open question. While Place and Hoff (2016) found that parental responses on Byers-Heinlein’s (2013) Language Mixing Scale correlated with language-diary-based measures of parental code-switching, Bail, Morini, and Newman (2015) observed a lack of concordance between parents’ self-reports of code-switching behavior and the actual number of code-switches they produced. We asked the parents in the present study to report not only on the frequency of their own code-switching, but also on the frequency of other individuals’ code-switching behaviors, and the reliability of these reports remains to be established. This approach may have been especially problematic for a subset of bilingual children in our study who were exposed to both of their languages only in the school setting (see Table S1 in Supplementary Materials).

We also did not collect information regarding the amount of input that the children received from each source because we were uncertain about how to incorporate this information into a measure of code-switching exposure. We therefore acknowledge that a lot of additional research is needed to establish reliable indexes of code-switching exposure. In the absence of such a measure at the current point in time, our measure is a viable option that has a number of advantages over the few available alternatives. For instance, because of its broad nature, it may be more sensitive to fluctuations in code-switching exposure than more fine-grained measures that may also be more difficult for the parents to evaluate (e.g., intra-sentential code-switching). At the same time, our measure of code-switching exposure is more fine-grained than the diary measure employed by Place and Hoff (2016), for example, because it clearly instructs the parents to report on the amount of code-switching that particular individuals produce.

In conclusion, we would offer the following cautious interpretation of our findings: Exposure to code-switching does not carry risks, and may in fact be associated with better language outcomes in children who are capable of processing such input. However, exposure to code-switching may not be optimal for language development in children who may have difficulties processing such input. Of course, in view of the limitations of the parent report measure of exposure to code-switching and in view of the rather weak, albeit significant interaction between verbal working memory capacity and exposure to code-switching, it is premature to offer any practical recommendations based on our findings. Notably, in our study, we targeted only typically-developing children, and therefore the next logical step for this line of research is to examine the association between exposure to code-switching and language outcomes in children with language impairment. Because working memory deficits are well-established in children with language impairment (e.g., Archibald & Gathercole, 2003; Ellis Weismer, Evans, & Hesketh, 1999; Montgomery, 2000), we would venture to hypothesize that our findings for the children with lower levels of verbal working memory would also pertain to children with language impairment. However, our findings in no way suggest that exposure to two languages is detrimental to language outcomes in bilingual children. Rather, they indicate a possibility that certain ways of structuring the bilingual language environment may be more optimal for the children who may have difficulty processing language.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The present project was supported by NIDCD Grants: R03 DC010465, R01 DC011750 to Margarita Kaushanskaya , and a Training Grant T32 DC005359 to Susan Ellis Weismer. We extend our gratitude to the families who participated in the present study, to the students in the Language Acquisition and Bilingualism Lab for their assistance with data collection and data coding, and to the schools in the Madison Metropolitan School district who generously aided in participant recruitment.

References

- Altarriba J, Kroll JF, Sholl A, & Rayner K (1996). The influence of lexical and conceptual constraints on reading mixed-language sentences: Evidence from eye fixations and naming times. Memory & Cognition, 24, 477–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archibald L, & Gathercole S (2006). Short-term and working memory in specific language impairment. International Journal of Communicative Disorders, 41, 675–693. doi: 10.1080/13682820500442602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bail A, Morini G, & Newman RS (2015). Look at the gato! Code-switching in speech to toddlers. Journal of Child Language, 42, 1073–1101. doi: 10.1017/S0305000914000695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentahila A, & Eirlys ED (1995). Patterns of code-switching and patterns of language contact. Lingua, 96, 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- Bobb SC, & Wodniecka Z (2013). Language switching in picture naming: What asymmetric switch costs (do not) tell us about inhibition in bilingual speech planning. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 25, 568–585. doi: 10.1080/20445911.2013.792822 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buac M, Gross M, & Kaushanskaya M (2016). Predictors of processing-based task performance in bilingual and monolingual children. Journal of Communication Disorders, 62, 12–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2016.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bultena S, Dijkstra T, & Van Hell JG (2015a). Language switch costs in sentence comprehension depend on language dominance: Evidence from self-paced reading. Bilingualism: Language & Cognition, 18, 453–469. doi: 10.1017/S1366728914000145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bultena S, Dijkstra T, & Van Hell JG (2015b). Switch cost modulations in bilingual sentence processing: evidence from shadowing. Language, Cognition, & Neuroscience, 30, 586–605. doi: 10.1080/23273798.2014.964268 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Byers-Heinlein K (2013). Parental language mixing: Its measurement and the relation of mixed input to young bilingual children’s vocabulary size. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 16, 32 – 48. doi: 10.1017/S1366728912000120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Byers-Heinlein K, Morin-Lessard E, & Lew-Williams C (2017). Bilingual infants control their languages as they listen. PNAS, 114, 34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1703220114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain K, Oakhill JV, & Bryant PE (2004). Children’s reading comprehension ability: Concurrent prediction by working memory, verbal ability, and component skills. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96, 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Cha K, & Goldenberg C (2015). The complex relationship between bilingual home language input and kindergarten children’s Spanish and English oral proficiencies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107, 935–953. 10.1037/edu0000030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chrysochoou E, Bablekou Z, Masoura E, & Tsigilis N (2013). Working memory and vocabulary development in Greek preschool and primary school children. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 10, 417–432. 10.1080/17405629.2012.686656 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cockroft K (2016). A comparison between verbal working memory and vocabulary in bilingual and monolingual South African school beginners: implications for bilingual language assessment. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 19, 74–88. 10.1080/13670050.2014.964172 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins J (1976). The influence of bilingualism on cognitive growth: A synthesis of research findings and explanatory hypotheses. Working Papers on Bilingualism, 9, 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins J (1979). Linguistic interdependence and the educational development of bilingual children. Review of Educational Research, 49, 222–251. 10.3102/00346543049002222 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins J (1984). Bilingualism and cognitive functioning In Shapson S and D’Oyley V (Eds.), Bilingual and multicultural education: Canadian perspectives (pp. 55–70). Clevedon, United Kingdom: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins J (2000). Language, power and pedagogy: Bilingual children in the crossfire. Clevedon, United Kingdom: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Daneman M & Carpenter PA (1980). Individual differences in working memory and reading. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 19, 450–466. 10.1016/S0022-5371(80)90312-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daneman M & Merikle PM (1996). Working memory and language comprehension: A meta-analysis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 3, 422–433. doi: 10.3758/BF03214546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis Weismer S, Evans J, & Hesketh L (1999). An examination of verbal working memory capacity in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 42, 1249–1260. 10.1044/jslhr.4205.1249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel de Abreu PMJ, Gathercole SE, & Martin R (2011). Disentangling the relationship between working memory and language: The roles of short-term storage and cognitive control. Learning and Individual Differences, 21, 569–574. 10.1016/j.lindif.2011.06.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engel de Abreu PMJ, & Gathercole SE (2012). Executive and phonological processes in second-language acquisition. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104, 974–986. 10.1037/a0028390 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fricke M, Kroll JF, & Dussias PE (2016). Phonetic variation in bilingual speech: A lens for studying the production-comprehension link. Journal of Memory and Language, 89, 110–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2015.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DW, & Wei L (2014). A control process model of code-switching. Language, Cognition, and Neuroscience, 29, 499–511. 10.1080/23273798.2014.882515 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gullifer JW, Kroll JF, & Dussias PE (2013). When language switching has no apparent cost: lexical access in sentence context. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 278. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlavac Marek (2018). stargazer: Well-Formatted Regression and Summary Statistics Tables. R package version 5.2.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=stargazer [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman AS, & Kaufman NL (2004). Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test, Second Edition Bloomington, MN: Pearson, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Kohnert KJ, & Bates E (2002). Balancing bilinguals II: Lexical comprehension and cognitive processing in children learning Spanish and English. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 45, 347–359. 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/027) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kormos J, & Sáfár A (2008). Phonological short-term memory, working memory, and foreign language performance in intensive language learning. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 11, 261–271. 10.1017/S1366728908003416 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leather CV, & Henry LA (1994). Working memory span and phonological awareness tasks as predictors of early reading ability. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 58, 88–111. doi: 10.1006/jecp.1994.1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky MG (2013). Head Start teachers’ vocabulary instruction and language complexity during storybook reading: Predicting vocabulary outcomes of students in linguistically diverse classrooms. Early Education and Development, 24, 640–667. doi: 10.1044/2014_JSLHR-L-12-0221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marian V, Blumenfeld HK, & Kaushanskaya M (2007). The Language Experience and Proficiency Questionnaire (LEAP-Q): Assessing language profiles in bilinguals and multilinguals. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 50, 940–967. 10.1044/1092-4388(2007/067) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuter RFI, & Allport A (1999). Bilingual language switching in naming: Asymmetrical costs of language selection. Journal of Memory and Language, 40, 25–40. 10.1006/jmla.1998.2602 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery J (2000). Verbal working memory and sentence comprehension in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 43, 293–308. 10.1044/jslhr.4302.293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno EM, Federmeier KD, & Kutas M (2002). Switching languages, switches palabras (words): An electrophysiological study of code switching. Brain and Language, 80, 188–207. doi: 10.1006/brln.2001.2588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoladis E, & Secco G (2000). The role of a child’s productive vocabulary in the language choice of a bilingual family. First Language, 20, 3–28. 10.1177/014272370002005801 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering S, & Gathercole SE (2001). Working Memory Test Battery for Children (WMTBC). London, UK: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Place S & Hoff E (2011). Properties of dual language exposure that influence two-year-olds’ bilingual proficiency. Child Development, 82, 1834–1849. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01660.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Place S, & Hoff E (2016). Effects and noneffects of input in bilingual environments on dual language skills in 21/2-year-olds. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 19, 1023–1041. 10.1017/S1366728915000322 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Proverbio AM, Leoni G & Zani A (2004). Language switching mechanisms in simultaneous interpreters: an ERP study. Neuropsychologia, 42, 1636–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2015). R: A language and environment for statistical computing R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria: URL: https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardelli LA (1992). Bilingualism and cognitive development in relation to threshold theory. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 21, 301–316. 10.1007/BF01067515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seigneuric A, & Ehrlich MF (2005). Contribution of working memory capacity to children’s reading comprehension: A longitudinal investigation. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 18, 617–656. 10.1007/s11145-005-2038-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Semel E, Wiig EH, & Secord WA (2003). Clinical evaluation of language fundamentals, fourth edition (CELF-4). Toronto, Canada: The Psychological Corporation/A Harcourt Assessment Company. [Google Scholar]

- Tare M, & Gelman SA (2011). Bilingual parents’ modeling of pragmatic language use in multiparty interactions. Applied Psycholinguistics, 32, 761–780. doi: 10.1017/S0142716411000051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Der Meij M, Cuetos F, Carreiras M, & Barber H (2011). Electrophysiological correlates of language switching in second language learners. Psychophysiology, 48, 44–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2010.01039.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen J, & Leseman P (2016). How do verbal short-term memory and working memory relate to the acquisition of vocabulary and grammar? A comparison between first and second language learners. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 141, 65–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2015.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yow WQ, & Markman EM (2016). Children increase their sensitivity to a speaker’s nonlinguistic cues following a communication breakdown. Child Development, 87, 385–394. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiig EH, Secord WA, & Semel E (2006). Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals- Fourth Edition Spanish. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt PsychCorp. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock RW, McGrew KS, & Mather N (2001). Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Cognitive Abilities and Tests of Achievement(3rd ed). Rolling Meadows, IL: Riverside. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.