To the Editor,

Teamwork, leadership, and non-technical skills are pivotal for successful resuscitation during cardiac arrest,1 as indicated by the European Resuscitation Council and the American Heart Association.2 However, we are facing unprecedented challenges to maintain effective resuscitation teamwork during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic.

There are several issues during resuscitation in cardiac arrest patients with suspected COVID-19 in the emergency department (ED) to be addressed. First, as many aerosol-generating procedures are provided during cardiopulmonary resuscitation, team members were separated into a contaminated group who works in a negative-pressure isolation room and anteroom, and a clean group in clean zone to reduce exposure to COVID-19-infected patients. Limited personnel in the isolation room made resuscitation less efficient than usual care. Second, unusual environment and limited resources in the isolation room impaired the teamwork of resuscitation. Third, the muffled voice due to personal protective equipment (PPE) made communication between team members more difficult. All these consequences on resuscitation in ED indicated the need for a novel teamwork model.3

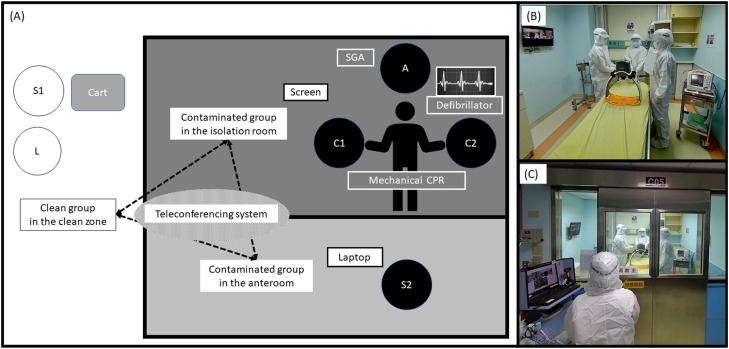

We re-designed an isolation-Airway-Circulation-Leadership-Support (iACLS) teamwork model from our original ACLS model4 to maintain high performance resuscitation and to reduce COVID-19 exposure of team members during the pandemic (Fig. 1 ). Four personnels were included in the contaminated group. Three of them donning PPE were assigned to the isolation room and worked as two teams. The airway team (1 personnel) applied advanced airway with supraglottic airway devices, ventilated with bag-valve mask connecting high-efficiency particulate air filter, and confirmed the advanced airway with a waveform end-tidal CO2 monitor. The circulation team (2 personnels) was responsible for recognizing shockable rhythm with defibrillator, setting up mechanical chest compression, and establishing intravenous routes and administrating medications. The other personnel, the support team, donning PPE in the anteroom served as a bridge of supplies and support. As for the clean group in the clean zone, the resuscitation team leader was assigned to give directions and to monitor the resuscitation, while another support team was assigned to support recording the resuscitation. The team leader in the cold zone coordinated the whole process. The model provided the basic concept of teamwork for high-quality resuscitation with minimal COVID-19 exposure of team members.

Fig. 1.

(A) Illustration of the modified teamwork model of resuscitation for cardiac arrest patients, iACLS model; (B) the picture of the isolation room; (C) the picture of isolation room viewed from the anteroom. SGA: supraglottic airway; CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation; A: airway team; C: circulation team; L: leader; S: support team.

To overcome the communication gap caused by separation of spaces, we applied a teleconferencing system, Cisco Webex® (Cisco Systems, Inc. San Jose, USA) in the iACLS model.5 The leader and all the team members could share audio-visual communication on the screens from separated spaces, facilitating the leadership by giving timely instructions to maintain good quality of resuscitation. The contamination group members could also call back on time to confirm the orders and feedback on the condition of the patient. Besides, direct visualization allowed the leader to maintain high quality of infection control throughout the resuscitation. Furthermore, the teleconferencing system provided better psychological support between team members by good communication.

Although our model is beneficial, non-technical skills and resuscitation teamwork should be modified according to the environment of different facilities. Evaluation and validation of the effectiveness of the iACLS model should be further investigated.

Funding source

None.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Hunziker S., Johansson A.C., Tschan F., et al. Teamwork and leadership in cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:2381–2388. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nolan J.P., Monsieurs K.G., Bossaert L., et al. European Resuscitation Council COVID-19 guidelines executive summary. Resuscitation. 2020;153:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sung C.W., Lu T.C., Fang C.C., et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department services acuity and possible collateral damage. Resuscitation. 2020;153:185–186. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chong K.M., Wu C., Lin J.J., et al. Advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) is all about Airway-Circulation-Leadership-Support (A-C-L-S): a novel cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) teamwork model. Resuscitation. 2016;106:e11–e12. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.07.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin C.H., Tseng W.P., Wu J.L., et al. A double triage and telemedicine protocol to optimize infection control in an emergency department in Taiwan during the COVID-19 pandemic: retrospective feasibility study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e20586. doi: 10.2196/20586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]